Abstract

The aim of this research is to analyze links between customer-based brand equity and customer engagement in the field of experiential services (e.g., private health clinics)—taking an emerging economy context as our reference. The authors put forth a chain of effects—based in Social Capital Theory—to test the impact of customer-based brand equity on customer engagement, mediated by satisfaction and customer reputation. Causal model estimation results suggest that customer-based brand equity has both a direct, positive impact on customer satisfaction and customer reputation and an indirect impact on customer engagement. The final section of the paper presents theoretical discussion of the results and the main implications for business practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Given the increasingly competitive nature of business environments, service firms must find new ways to deliver value to their customers (Ostrom et al. 2015). The broad range of products and services on offer—coupled with the proliferation of contact channels—make the overall customer experience key to understanding customer-based brand equity (CBBE) and customer satisfaction. Hence, firms must pay close attention to all marketing activities aimed at providing customized experiences throughout the relationship (Cambra-Fierro et al. 2020a; Hernández-Ortega and Franco 2019; Bolton et al. 2014) such as brand management. The Marketing Science Institute has recently highlighted brand differentiation through customer experience as a research priority for 2020–2022—especially with regard to experiential services and highly competitive markets (Kim and Lee 2017).

A number of authors (Stein and Ramasesshan 2020; Srivastava and Kaul 2014; Verhoef et al. 2009) suggest that previous experiences influence intangible resources such as brand equity and reputation, as well as future decisions and experiences. When experiences are properly provided and managed, firms will be in a position both to boost customer satisfaction and build and bolster market positioning based on a solid reputation (Roberts and Dowling 2002). Corporate reputation—linked to brand equity (Hollenbeck 2018)—is an intangible, hard-to-imitate strategic asset, providing an excellent opportunity to respond to stakeholder expectations and foster successful experiences (Veloutsou 2007; Hoeffler and Keller 2003). In this way, feelings, memories, and images can be effectively linked to the brand.

Despite the impact of experiential factors on corporate reputation, the literature on the topic remains scarce, especially in emerging economy contexts. Contributions by Kandampully et al. (2018) and Khan and Fatma (2017) are notable exceptions; however in both cases, analysis is limited to developed Western economies—and existing research clearly indicates that Western marketing strategies and approaches are not necessarily effective in emerging markets (Arditto et al. 2020; Herstein et al. 2017).

Having identified this gap in the literature, the aim of the present research is twofold: on one hand, to analyze consumer perceptions regarding brand equity in highly experiential service contexts (e.g., private clinics) and on the other, to assess the impact on customer engagement. CBBE reflects how consumers think and feel about a brand (Datta et al. 2017); hence, in the present paper, we propose that CBBE drives a chain of effects impacting corporate reputation, customer satisfaction and customer engagement.

In many developed and developing countries, healthcare is a key public service industry (Hau 2019). In fact, the literature has identified healthcare contexts as a top service research priority (Ostrom et al. 2015). Our study is even more relevant in the current pandemic and post-pandemic world, where healthcare is an absolute priority for most people (Campbell et al. 2020). Public healthcare acts as a guarantor of universal access—even if some choose private sector services for general care, testing and diagnosis out of a belief that they will obtain better, more agile service (perhaps because private healthcare facilities are often better equipped with modern infrastructures and technology). In this respect, factors like brand equity and reputation determine hospital/clinic positioning, potentially having a decisive impact on patient/user decision-making and short-term intent. The novelty and overall interest of this study is also enhanced by the fact that research was carried out in an emerging economy context. In many developing countries, the public healthcare system has collapsed due to the onslaught of COVID-19 and elements like use of new technologies or adoption of respectful, patient-centered care policies—cornerstones of private healthcare—are positively impacting patient/user opinions (Traiki et al. 2020).

With a view to reach our objectives, the paper is structured as follows: Conceptual framework presents key research variables: CBBE, corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and customer engagement. The third section illustrates our conceptual model and hypotheses development. Methodological details are provided in Research methodology and results, in Model estimations and results. Our theoretical discussion, key recommendations for management and conclusions are presented in the final section of the paper.

2 Conceptual framework

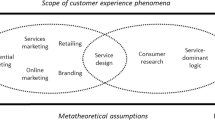

2.1 Experiential services and branding

In line with Bolton et al. (2014) and Verhoef et al. (2009), customer experience is usually conceptualized as holistic in nature, involving customers’ cognitive, affective, emotional, social and sensory responses to stimuli from firms. The term covers experiences accumulated throughout the different phases of the customer-firm relationship: search, purchase, consumption and post-consumption—and includes all customer journey touch points (Neslin et al. 2006). This thinking is consistent with the notion that the customer's service experience is inevitably a process rather than an outcome (Yang et al. 2012).

From an experience management standpoint, cultivating proposals that enrich the customer journey and engage consumers before, during, and after purchase is essential to creating enjoyable experiences (Hernández-Ortega and Franco 2019; de Keyser et al. 2015; Verhoef et al. 2009), meeting customer expectations, building loyalty and shoring up commitment (de Lima et al. 2020; Pappu et al. 2005). This is especially relevant for highly experiential services (Fuentes-Blasco et al. 2017), where meeting expectations boosts credibility, brand equity and differential competitive advantage (Krystallis and Chrysochou 2014; Berry 2000; Bharadwaj et al. 1993) while nurturing brand-consumer emotional connectedness (Hunter-Jones et al. 2020; Ostrom et al. 2015).

In this sense, elements like brand equity and corporate reputation act as signals that facilitate consumer decision-making processes (Tournois 2015). Moreover, successfully engaged customers are more likely to repurchase, recommend the brand and co-create, among other effects. This is the virtuous circle we seek to analyze here, assuming that—in the case of experiential services and depending on the nature of the particular service (e.g., private healthcare clinics)—there is a risk continuum associated with the purchase decision.

Hau (2019) has recently pointed out that healthcare patients usually experience stress due to pain, anxiety, fear, and outcome uncertainty. Hence, we believe factors like CBBE and brand reputation may act as ex-ante cues to alleviate such uncertainty. Moreover, if we follow the classical construct of customer value (Zeithaml 1988), elements like money, effort, time, opportunity, prestige, convenience and emotions all influence expectations—while factors like perceived quality, satisfaction and prestige may emerge as outcomes of service provision (Babin and James 2010). In the case of healthcare, problem solving and achieving wellness are key to attaining user satisfaction. From this perspective, customer value is understood from a consumer experience standpoint, impacting service provider image and reputation down the line (Helkkula and Kelleher 2010; Heinonen et al. 2010).

2.2 From customer-based brand equity to customer engagement in experiential services: the case of emerging LATAM economies

Building a strong brand translates as significant competitive advantage (Keller 2003; Aaker 1991). In the case of experiential services, active consumer interaction and engagement is recommended (Boksberger and Melsen 2011). Leone et al. (2006) and Keller (1993), among others, point out that CBBE encompasses, on one hand, consumer attitudes and actions towards the brand; and on the other, a set of associations that evoke attributes stored in consumer memory including prestige, safety, trust, loyalty, honesty, profitability and security—boosting value and enhancing image and reputation. In this vein, the extensive corpus of CBBE literature has proposed a range of dimensional conceptualizations for the construct based on seminal contributions by Aaker (1996) and Keller (1993). Aaker affirms that brand awareness, brand associations or brand image, perceived quality and brand loyalty are the fundamental factors that generate added value for customers. Keller argues that CBBE occurs when consumers are familiar with a brand and make unique, favorable affective and cognitive associations—potentially impacting corporate reputation and customer satisfaction, among other elements.

Corporate reputation is a structural extension of brand concept—built over time from an accumulation of positive and/or negative perceptions regarding an organization’s actions, allowing for projections about future behavior (Janney and Gove 2011; Walker 2010; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). A positive corporate reputation fosters favorable perceptions like prestige, honesty, responsibility, solidarity, empathy, and trust (Umasuthan et al. 2017), hence positive responses to the company (Kim et al. 2019; Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). When managed effectively, reputation will become an intangible asset—nurturing a sustainable competitive advantage by providing value, prestige, and recognition to the firm (Agarwal et al. 2015). Wagner et al. (2009) suggest that a positive corporate reputation generates a favorable attitude towards company products/services (e.g., perceived quality, reliability) and certain positive post-purchase behaviors (e.g., loyalty, recommendations).

In the case of experiential services, corporate reputation is a far more relevant asset in the quest to shore up business sustainability over time (Lallement et al. 2020). Service delivery must be enriched with experiences that boost brand equity and nurture solid corporate reputation-building—a catalyst for customer engagement. To this end, generating synergistic actions is essential, across each and every dimension of brand equity: awareness, image, perceived quality and loyalty (Keller 1993), since the final objective is to satisfy consumers, encourage identification with the company and garner adequate levels of trust and commitment (Prentice and Nguyen 2020; Moliner-Velázquez et al. 2019; Keiningham et al. 2017).

For all these reasons, strategies designed to generate positive consumer experiences must be implemented from the understanding that satisfaction is objective to a degree but fundamentally subjective and emotional in nature. The literature suggests that satisfaction surfaces when consumer experiences are rewarding and expectations exceeded (de Lima et al. 2020; Gustafsson et al. 2005). Satisfaction powers positive relationships, yielding outcomes like loyalty, repurchase and brand recommendation (Shankar et al. 2003). Reliable brands that fulfill the value proposition, foresee and respond to consumer concerns and reinforce perceived quality in present/past consumer experiences are key to achieving satisfaction (Hernández-Ortega and Franco 2019; Meesala and Paul 2018; Kumar et al. 2013)—the topsoil for growing a solid corporate reputation. All of this together grows strong customer relationships, which in turn, have a positive impact on customer intentions and behaviors (Punyatoya 2019; Su et al. 2016).

Creating lasting consumer-bonds, then, is of the essence—becoming an indispensable aspiration for service providers. Today’s consumers play a much more active role in information/recommendation-seeking and decision-making processes (Cambra-Fierro et al. 2018a). Many are even willing to co-create throughout design and service delivery processes (Lee 2019; Cambra-Fierro et al. 2018b). These actions are grouped under the umbrella term, customer engagement, defined by van Doorn et al. (2010) as a set of non-transactional behaviors springing from consumer motivational aspects, which have a deferred impact on the commercial outcome of the relationship. In such an interconnected context—in which the Internet and social media play a decisive role—the goal is no longer limited to achieving consumer satisfaction and repurchase; it also involves building an active value link to the company through behaviors such as recommendations or co-creation, reinforcing the perceived value of the experience on the part of consumers (Obilo et al. 2020; Hernández-Ortega and Franco 2019; Álvarez-Milán et al. 2018; Harrigan et al. 2017). An active, engaged consumer, for instance, feels motivated to post positive comments online and share their satisfaction via social media. Testimonials of this sort are considered more reliable and hence are more easily remembered and more convincing than company-controlled messages (Huerta-Álvarez et al. 2020; de Matos and Rossi 2008). This, in turn, contributes to boosting brand equity and building positive corporate reputation. This virtuous circle has been discussed earlier in this section and analyzed further in this paper. In the case of experiential services, every effort should be made to maximize hedonic value and strengthen satisfactory memories (An and Han 2020)—with a view to reinforce brand equity and ensure that consumers not only come back for more (repurchase), but also talk about and recommend the service on social media and elsewhere online (Pansari and Kumar 2017).

Notably, however, most emerging LATAM economies are characterized by low scores in the long-term orientation dimension (Hofstede, 2021): Colombia, 13; Argentina, 20; Paraguay, 20; Bolivia, 25; Uruguay, 26; Peru, 25; Chile, 31. These scores reveal a relatively small propensity to save for the future and a focus on achieving quick results. They also suggest that perhaps the antecedents proposed in the literature for long-term outcomes—e.g., customer engagement—do not apply to the extent that they do in more long-term oriented cultures; hence, we could expect variations in the virtuous circle described earlier.

3 Hypothesis development

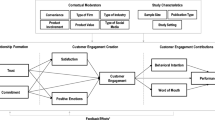

This research aims to analyze the relationship between CBBE, reputation, customer satisfaction, and engagement in the context of experiential services. Social Capital Theory (SCT) allows us to integrate the set of hypotheses shown in Fig. 1 and developed below.

SCT considers aspects linked to trust, transparency and reciprocity—together with relational elements that act as a signal, enabling us to anticipate future behaviors (Putnam 1993,2000; Ostrom 1991). Social capital springs from the interaction between different agents; hence, social networks based on norms of reciprocity and trust enhance societal efficiency. For all parties involved, mutually satisfactory relationships are built on the basis of social capital (Sen and Cowley 2013). Moreover, corporate reputation legitimizes company activity—becoming an essential intangible asset for understanding interactions with a key stakeholder: the customer. In our model, CBBE—via a chain of effects—positively impacts both corporate reputation and perceived satisfaction. These factors, in turn, determine the degree of customer engagement in the form of reciprocal customer behavior.

Seminal works by Aaker (1996) and Keller (1993) highlight the importance of brand equity to understanding better positioning with respect to competitors and consumer perceptions of company products, and purchasing decisions. Brand equity represents the usefulness or added value that the brand brings to a product or service (Hur et al. 2014)—thus becoming an asset that bolsters measurable and tangible benefits and contributing to growing a knowledge/value differential for both the company and the customer. CBBE guides consumers and, to some extent, equips them to anticipate quality and satisfaction (Sürücü et al. 2019). Consumers perceive that the brand itself adds value—connecting to one-of-a-kind positive associations and memories, and increasing familiarity with company products/services (Keller 1993). Higher perceived brand equity leads to higher levels of satisfaction (Brady et al. 2008; Esch et al. 2006; Zeithaml 1988). Moreover, brand equity is a catalyst for building robust, positive corporate reputations (Argenti and Druckenmiller 2004). In the case of services, in general, and experiential services, in particular, brand equity generates satisfaction and is decisive in reducing risk of adverse selection associated with purchasing decisions (Kim and Park 2017; Nassar 2017; Radojevic et al. 2015). Foroudi (2019) highlights the consistency of brand equity as an antecedent to brand reputation. Take the case of healthcare services, for instance: hospital brand recognition is associated with quality of care, medical staff expertise and availability of state-of-the-art equipment to meet patient needs (Khosravizadeh et al. 2020). Based on the above arguments, we put forth the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

CBBE has a positive impact on customer satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2

CBBE has a positive impact on corporate reputation.

With regard to service provision, authors like Walsh and Beatty (2007) promote building corporate reputation by way of customer satisfaction. Such authors also conclude that a good reputation positively impacts customer responses, growing satisfaction-fueled value and credibility. Likewise, customer engagement involves a high degree of linkage and commitment (Brodie et al. 2011; van Doorn et al. 2010); consolidating relationships that go beyond a mere succession of transactions (Kumar and Nayak 2018). Hence, engagement becomes the catalyst for robust long-term relationships involving repeat purchase and other high-value behaviors like posting of ‘likes’, online reviews and co-creation of products and services (Lee 2019; Brodie et al. 2011; Calder et al. 2009). From a relationship marketing perspective, the consensus is that satisfaction is a fundamental premise underpinning consumer willingness to co-create close bonds of this sort (Cambra-Fierro et al. 2016). Moreover, from the standpoint of social capital theory, we can assume that consumers will react reciprocally when their expectations are fulfilled (Olavarría-Jaraba et al. 2018)—a reality which firms signal via corporate reputation (a sign of confidence and promise). Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 3

Customer satisfaction has a positive impact on corporate reputation.

Hypothesis 4

Customer satisfaction has a positive impact on customer engagement.

Hypothesis 5

Corporate reputation has a positive impact on customer engagement.

4 Research methodology

4.1 Data collection and sample

Emerging economies can be defined as countries showing speedy economic development, where government policies favor economic liberalization and free markets. Peru has been classified as an emerging economy, according to the annual Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) ranking based on major world stock indexes (2019). The MSCI numbers highlight Peru's pull and vast international trade potential: among Latin America's fastest growing economies in recent years—3rd in the 2018 Institute for Management Development’s LATAM overall competitiveness ranking (just behind Chile and Mexico)—in just over 15 years, Peru’s GNI per capita has tripled from $2,010, in 2000, to $5,970 in 2017 (The World Bank, 2019). Most recently, the literature has considered Peru as an emerging economy of reference as well (e.g., Arditto et al. 2020; Cambra-Fierro et al. 2020b; Flores-Hernández et al. 2020).

Data were collected by means of a self-administered, face-to-face questionnaire by trained interviewers. Simple random sampling was used to select respondents from among private health clinic clients. Managers at several private clinics in the Lima metropolitan area were asked to approach patients in a number of specialist treatment waiting rooms to explain the questionnaire and purpose of the study. Nineteen clinics authorized our research. Similar methods involving approaching potential respondents at reference sites have been used in previous studies to reduce sampling bias and obtain a good respondent mix (Yani-de-Soriano et al. 2019; Kok and Fon 2014; Keillor et al. 2007). The interception method was deemed appropriate for our purposes as it enabled interviewers to screen potential respondents for eligibility and seek clarification where needed.

Field work was carried out between June and September 2018, achieving 300 complete, valid surveys with a sampling error of 5.66% (p = q = 0.5) assuming an infinite population. The overall sample shows a slightly higher presence of women (53%). Table 1 lists the main characteristics of our sample.

4.2 Measurement scales

To measure research model constructs, our questionnaire includes previously validated scales and was adapted to the private healthcare context (see Appendix Table 6). In line with Keller (1993) and Aaker (1991), we consider the multi-item dimensions of CBBE—awareness: 3 items adapted from Ferns and Walls (2012) and Arnett et al. (2003); image: 4 items adapted from Netemeyer et al. (2004); service quality: 5 items adapted from Aaker (1996) and Dodds et al. (1991); and loyalty: 4 items adapted from Yoo and Donthu (2001) and Yoo et al. (2000). Satisfaction was measured using a 6-item scale adapted from Fuentes-Blasco et al. (2017), Gelbrich (2011), and Nesset et al. (2011). Our corporate reputation scale comprised 5 items adapted from López-Pérez et al. (2017) and Martínez and Rodríguez del Bosque (2016). Finally, customer engagement was measured using a 6-item scale adapted from Cambra-Fierro et al. (2016), van Doorn et al. (2010), and Sprott et al. (2009). All items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1, “strongly disagree” to 7, “strongly agree”). Respondent gender and age were included as control variables.

To ensure translation equivalence, we adopted the strategy put forth in Yani-de-Soriano et al. (2019): first translating the questionnaire into Spanish for use in Peru via an iterative process of translation/back-translation by a team of bilingual speakers (Brislin et al. 1973). A concept-driven rather than a language or translation-driven, approach was used to check for linguistic nuances (Erkut et al. 1999; Barnard 1982).

Questionnaires were pre-tested (Douglas and Craig 2007) to detect potential ambiguity, improve item sequencing and wording and ensure that all items worked well in an actual-use scenario (Brislin 1986). The pre-test was conducted with 5 academic experts and 6 private healthcare patients to verify clarity of all items with a view to avoid any ambiguity in the wording. Pre-test respondents were asked whether they understood all instructions for completing the survey and if question wording was clear; they were also asked if response sheet format was appropriate, how long it took to complete and if they could provide any ideas for improving the questionnaire. Hence, our final questionnaire was the result of a rather exhaustive refining process.

4.3 Common bias method

Questionnaires were completed anonymously with a view to avoid common method variation problems; respondents were informed that there were no right or wrong answers. Once the information had been collected and purged, we checked for common bias problems using Harman’s one-factor technique. Our results show that the dominant factor explains 18.65% of the variance, well below the recommended maximum threshold of 50%. Likewise, none of the latent construct correlations shown in Table 3 were above 0.9 (Bagozzi et al. 1991), and VIF values associated with the latent constructs listed in Table 5 were below the maximum threshold of 3.3 (Kock and Lynn 2012). Hence, our data indicate that common method bias is not a problem in our study.

5 Model estimations and results

Partial least squares (PLS) path modeling using Smart PLS 3.2.9 software was our choice for model hypothesis verification (Ringle et al. 2015). This choice is justified given that our objective was to predict customer engagement in experiential service contexts via ordinary least squares estimation—a variable on which there is only a limited body of research (Roldán and Sánchez-Franco 2012). Moreover, this type of modeling is suitable when the measurement scales contain a small number of items (Barclay et al. 1995), and does not impose restrictions on data distribution (Chin 1998).

5.1 Measurement model estimates: scale validity and reliability

First, we opted for a principle component-based estimation approach using PLS to estimate a first-order measurement model considering all reflective items towards their latent construct (Chin et al. 2013). We then assessed measurement scale reliability and internal consistency using Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability indicators. All first-order constructs show values for both indices above the recommended minimum threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al. 2017), as seen in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, we were able to verify the convergent validity of measurement scales: all standardized loadings associated with observable items are significant at 99%; all average variance extracted values are greater than 0.5 (Hair et al. 2017). Likewise, discriminate validity was verified using the Fornell and Larcker criterion (1981). All correlations between pairs of latent factors are lower than the square root of the AVE for each construct (see Table 3). Moreover, the largest heterotrait-monotrait correlations ratio (HTMT) is 0.86, falling within the recommended threshold of 0.9 (Henseler et al. 2015).

The SRMR fit index is 0.062, below the 0.08 cut-off (Hu and Bentler 1999), allowing us to conclude that our modeling is appropriate. Moreover, we consider CBBE to be a second-order construct, comprising the dimensions of image, awareness, perceived quality, and loyalty—in line with recent studies (e.g., Frías et al. 2018; Gómez et al. 2015; Wong and Teoh 2015)—using latent variable scores as formative higher-order construct estimation indicators (see Table 4).

As seen in Table 4, our weights are significant at 1% (p < 0.01). Moreover, absence of multicollinearity issues was verified following procedure proposed by Sarstedt et al. (2019): our variance inflation factor (VIF) values are between 1.90 and 2.68—clearly below the 3.3 benchmark (Kock and Lynn 2012).

5.2 Structural model estimation

With a view to verify our research hypotheses, we proceeded to estimate the causal relationships between constructs and their significance, using the bootstrapping method with a resampling of 5000. This level of bootstrapping provides standard error and t-statistics for evaluating structural coefficient significance (Henseler et al. 2009). Results for path coefficients/direct effects are provided in Table 5, along with a number of fit indexes.

Results shown in Table 5 indicate that CBBE has a significant and positive effect both on customer satisfaction (β = 0.834, p < 0.01) and corporate reputation (β = 0.382, p < 0.01)—confirming research hypotheses H1 and H2. We can also affirm that customer satisfaction has a significant, positive impact on corporate reputation (β = 0.382, p < 0.01) and customer engagement (β = 0.499, p < 0.01), confirming hypotheses H3 and H4. Finally, our data show corporate reputation to have a significant, positive impact on customer engagement (β = 0.255, p < 0.01); hence, H5 is confirmed.

With regard to overall model assessment, the adjusted coefficients of determination (R2) are greater than 0.4 (see Table 5)—providing sufficient support for concluding that endogenous constructs have moderate explanatory power (Hair et al. 2017). The CBBE construct, specifically, helps explain satisfaction to a large extent, as effect size (f2) is greater than 0.35 (Cohen 1988). Finally, satisfaction moderately explains corporate reputation and customer engagement—with f2 values between 0.02 and 0.15 (see Table 5).

Predictive relevance was evaluated by means of the Stone-Geisser test (Q2) using the resampling blindfolding technique. Our results for all bases show Q2 values greater than 0, as seen in Table 5; hence, we confirm that our model has predictive relevance (Fornell and Cha 1994).

Finally, we ensured there were no multicollinearity issues that could skew regression results for our model. As seen in Table 5, our VIF values are below the 5.0 threshold proposed by Kock and Lynn (2012), allowing us to discard this potential problem.

6 Discussion and conclusions

6.1 Theoretical discussion

Experiential content is becoming increasingly relevant as an element of differentiation and positioning. From a consumer behavior standpoint, the way in which the purchase and/or user experience is perceived is crucial to understanding the degree of customer satisfaction (e.g., Hernández-Ortega and Franco 2019). Rooted in this fundamental premise, our research assumes the challenge of assessing the extent to which CBBE impacts customer satisfaction, corporate reputation and—via a virtuous circle—consumer engagement. Moreover, having chosen an emerging economy as our reference for empirical study enhances the interest of our results.

The results of this study have remained relevant and robust throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and into the post-pandemic period. Factors like CBBE and healthcare provider reputation can determine patient choice via expectations and service provision perceptions. Hau (2019) and Babin and James (2010), among others, indicate that antecedents to service provision help explain both patient decisions and perceived outcomes—having an impact, as well, on the future of service provider-user relationships and provider positioning.

Our results—derived from empirical analysis of a sample of customer opinions regarding highly experiential services (private health clinics)—demonstrate that CBBE has a decisive impact on both the degree of perceived satisfaction (H1) and corporate reputation (H2). Insofar as brand equity contributes to building a robust corporate reputation, which acts as a guarantor for company performance—and, in the case of experiential services, is key to reducing the risk of adverse selection (e.g., Radojevic et al. 2015)—our data are in line with ideas put forth by authors like as Sürücü et al. (2019) and Brady et al. (2008). Our study also highlights the consistency of consumer satisfaction as an antecedent to corporate reputation (H3), as Foroudi (2019) indicates. Moreover, for the context under scrutiny, the data reveal that satisfaction drives a decisive degree of customer engagement (H4). Finally, our results confirm that corporate reputation does indeed have a significant impact on engagement (H5).

As mentioned earlier in this paper, such results are in line with the main ideas underpinning Social Capital Theory (Sen and Cowley 2013). Positive company-customer interactions weave social networks based on trust and reciprocity. More specifically—in the context of this study—customer satisfaction and corporate reputation legitimize company actions, becoming intangible assets explaining successful interactions and engaged customers.

The results obtained can be explained by the risk associated with the decision in question: consumers tend to be much more engaged when facing decisions regarding personal health and healthcare. Hence, it would be highly advisable to enhance service delivery with enriched experiences—with a view to positively impact customer satisfaction and corporate reputation, and encourage consumer engagement. A practical example of this is increased availability of wearable healthcare devices, for instance—one of the latest trends in private healthcare, aimed at improving user experiences (Lee and Lee 2020). At the end of the day, all interactions and touchpoints are opportunities to boost brand equity, build reputation, and bolster customer connections.

Strikingly, the data support all proposed hypotheses. Given Peru’s low score of 25 in the long-term orientation dimension (Hofstede, 2021), we had presumed that the virtuous circle from CBBE to customer engagement would vary vis-a-vis more long-term oriented cultures. Yet, our results confirm all links put forth in the chain of effects. Given that we are analyzing a highly experiential, risky, hedonic and often expensive service, high degrees of consumer engagement and income level may explain the unexpected similarity to results for more long-term oriented, developed Western economies.

6.2 Recommendations for best practices

In situations of great risk and uncertainty, consumers tend to choose established, well-known firms, capable of managing complex situations effectively—often firms with which they have had previous experience or which have been recommended by other users. In such a context, building robust, lasting relationships with users is absolutely essential. This is the case of private health clinics, where highly experiential service profiles call for actions designed to shore up CBBE, with a view to engage customers.

From a business practice standpoint, customer experience strategic management analysis recommends growing customer-based brand equity aimed at sparking emotional connections capable of supporting successful business-customer relationships. It is essential, then, for companies to behave proactively and act effectively to enrich customer experiences. Business model innovation shapes customer experiences in the hopes of boosting competitiveness in changing environments and contexts displaying high degrees of intangibility and decision-associated risk.

Opportunities for positive, interactive experiences across all brand equity dimensions enhance consumer perceptions and increase the chances of satisfying customers. Experience-based economies involve changes in consumption patterns, where the search for positive interactive experiences reinforces the value of CBBE. Interest in CBBE exceeds interest in quality of service—prioritizing emotions above all else. Technology can be harnessed to personalize consumer experiences, thus enhancing customer perceptions and boosting satisfaction.

Consumers not only expect to have their needs met; expectations must be exceeded and satisfaction increased with every purchasing experience (e.g., de Lima et al. 2020). Hence, we recommend designing strategies and actions aimed at garnering consumer loyalty and building long-term emotional bonds by way of satisfying, memorable experiences.

Another strategy is for firms to strive to place each individual customer at the forefront of their focus and align actions with consumer expectations in the quest for “tailored” services. We suggest starting with a detailed study of the characteristics, needs, tastes and expectations of each customer with a view to personalize their experience, boost brand image, and build company credibility—especially in firms that deliver highly experiential services. This approach will be more advisable in sectors like healthcare where decision-associated risk is greater; hence, the degree of customer involvement in analysis and decision-making processes is greater as well. That said, we must recognize that a disconnection may occur between what companies aim to generate in terms of experiences and what consumers actually perceive. Understanding and supporting customers better throughout analysis, decision-making, use and post-purchase processes will help bring expectations and perceived real value into closer alignment—reinforcing CBBE and creating the chain of positive effects that we put forth in our causal model.

New technologies, social and digital media, and the plethora of available channels and platforms allow for greater connectedness and interaction with consumers—providing firms numerous opportunities to support customers throughout their journey. Companies in general—and experiential service providers in particular—cannot afford to turn their backs on technology; especially so in the case of emerging economies. In the specific case of private health clinics, technology plays a very relevant role in creating and communicating CBBE. Technology is associated with innovation, efficiency and competence—images that may not only reinforce CBBE but also create multiple channels and touchpoints for interacting with customers as well.

Finally, in this age of pandemic more than ever, firms are being given the opportunity to grow their brand’s differential value through empathic action and solidarity—i.e. developing a set of experiences that nurture an emotional connection and project the company’s role as a committed stakeholder who prioritizes service vocation in benefit of the common good. Strict, speedy compliance with biosafety protocols and smooth transition and commitment to addressing customer queries via remote communication tools/digital media are two ways healthcare providers can shore up brand image and build corporate reputation—essentially showing they are on board when it comes to putting patient health and safety first. Such actions can drive changes in consumer perceptions, attitudes and warmth of the relationship, all of which are valued by many users (Curioso and Galán-Rhodes 2020). Golinelli et al. (2020) note that COVID-19 is favoring the digital transition and many private clinics have been quick to provide effective tech solutions—bolstering the reputation of healthcare providers already enjoying a strong position by transmitting a greater sense of security to customers in this uncertain environment.

6.3 Conclusions

This study was carried out in the context of an emerging economy—Peru—where there is still a long way to go in terms of brand equity, in general, and experiential services in particular. Our research shows the existence of a virtuous circle from CBBE to customer engagement in a highly experiential service context—probably due to a high degree of customer engagement in analysis, decision-making and perceived outcomes. Specific customer profiles of this sort seem to explain why our findings for an emerging, short-term orientated economy are analogous to existing results for more developed Western economies.

This pioneering study allowed the authors to deepen analysis of a number of key concepts and contribute results and recommendations of interest—not only for academia but also for business practice as well. However, despite the relevance of our paper and the rigor with which our empirical research was carried out, we must acknowledge certain limitations. First, since the study is based on personal opinions, some bias may be present in the data. In anticipation—following recommendations by Podsakoff et al. (2003) and Podsakoff and Organ (1986)—we adopted a series of strategies aimed at minimizing any potential bias: guaranteeing respondent anonymity, clarifying the inexistence of correct/incorrect answers and adapting previously validated scales to the context of analysis. Secondly, our sample size is around 300 responses. While initially this might seem small, the fact that it is a random sample has allowed us to effectively achieve our research objectives. Finally, our model is likely to include additional variables. Although admittedly this was not our initial objective, we believe these variables provide a solid basis for future research: replicating our study in other service industries displaying different degrees of experiential intensity would contribute to assessing the impact of customer engagement and experiential perception on the chain of effects we propose in our model. Additionally, replicating the study in other emerging economies would strengthen conclusions and contribute to identifying additional cross-cultural patterns of interest in the field of experiential services from both a theoretical and a management perspective.

References

Aaker D (1991) Managing brand equity. Free Press, New York

Aaker D (1996) Measuring brand equity across products and markets. Calif Manage Rev 38(3):102–120. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165845

Agarwal J, Osiyevskyy O, Feldman PM (2015) Corporate reputation measurement: alternative factor structures, nomological validity, and organizational outcomes. J Bus Ethics 130(2):485–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2232-6

Álvarez-Milán A, Felix R, Rauschnabel A, Hinsch C (2018) Strategic customer engagement marketing: a decision-making framework. J Bus Res 92:61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.017

An MA, Han SL (2020) Effects of experiential motivation and customer engagement on customer value creation: analysis of psychological process in the experience-based retail environment. J Bus Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.044

Arditto L, Cambra-Fierro JJ, Fuentes-Blasco M, Jaraba AO, Vázquez-Carrasco R (2020) How does customer perception of salespeople influence the relationship? A study in an emerging economy. J Retail Consum Serv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101952

Argenti PA, Druckenmiller B (2004) Reputation and the corporate brand. Corp Reput Rev 6(4):368–374. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540005

Arnett DB, Laverie DA, Meiers A (2003) Developing parsimonious retailer equity indexes using partial least squares analysis: a method and applications. J Retailing 79(3):161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(03)00036-8

Babin BJ, James KW (2010) A brief retrospective and introspective on value. Eur Bus Rev 22(5):471–478. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555341011068895

Bagozzi R, Yi Y, Phillips L (1991) Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm Sc Quart 36:421–458. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393203

Barclay D, Higgings C, Thompson R (1995) The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: personal computer adoption and use as illustration. Technol Stud Spec Issue Res Methodol 2(2):285–309

Bebko CP (2000) Service intangibility and its impact on consumer expectations of service quality. J Serv Mark 14(1):9–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040010309185

Berry LL (2000) Cultivating service brand equity. J Acad Market Sci 28(1):128–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300281012

Bharadwaj SG, Varadarajan PR, Fahy J (1993) Sustainable competitive advantage in service industries: a conceptual model and research propositions. J Marketing 57(4):83–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252221

Boksberger E, Melsen L (2011) Perceived value: a critical examination of definitions, concepts, and measures for the service industry. J Serv Mark 25(3):229–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111129209

Bolton R, Gustafsson A, McColl-Kennedy N, Sirianni N, Tse D (2014) Small details that make differences: a radical approach to consumption experience as a firm’s differentiating strategy. J Serv Manage 25(2):253–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-01-2014-0034

Brady MK, Cronin JJ Jr, Fox GL, Roehm ML (2008) Strategies to offset performance failures: the role of brand equity. J Retailing 84(2):151–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.04.002

Brislin RW (1986) The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WJ, Berry JW (eds) Cross-cultural research and methodology series,8. Field methods in cross-cultural research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 137–164

Brislin RW, Lonner WJ, Thorndike RM (1973) Cross-cultural research methods. Wiley, New York

Brodie RJ, Hollebeek LD, Juric B, Ilic A (2011) Customer engagement: conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J Serv Res 14(3):252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

Calder BJ, Malthouse EC, Schaedel U (2009) An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. J Interact Mark 23(4):321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2009.07.002

Cambra-Fierro J, Melero-Polo I, Sese FJ (2016) Can complaint-handling efforts promote customer engagement? Serv Bus 10(4):847–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-015-0295-9

Cambra-Fierro J, Melero-Polo I, Sese FJ (2018a) Customer-firm interactions and the path to profitability: a chain-of-effects model. J Serv Res 21(2):201–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517738369

Cambra-Fierro J, Melero-Polo I, Sese FJ (2018b) Customer value co-creation over the relationship life cycle. J Serv Theor Pract 28(3):336–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-01-2017-0009

Cambra-Fierro J, Flores-Hernández J, Pérez L, Valera-Blanes G (2020) CSR and branding in emerging economies: the effect of incomes and education. Corp Soc Responsibil Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2000

Cambra-Fierro J, Melero-Polo I, Patrício L, Sese FJ (2020) channel habits and the development of successful customer-firm relationships in services. J Serv Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520916791

Campbell M, Inman J, Kirmani A, Price L (2020) In times of trouble: a framework for understanding consumers’ responses to threats. J Consum Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa036

Chaudhuri A, Holbrook MB (2001) The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J Marketing 65(2):81–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

Chin WW (1998) The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In: Marcoulides GA (ed) Modern methods for business research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London

Chin WW, Thatcher JB, Wright RT, Steel D (2013) Controlling for common method variance in PLS analysis: the measured latent marker variable approach. In: Abdi H, Chin WW, Esposito Vinzi V, Russolillo G, Trinchera L (eds) New perspectives in partial least squares and related methods. Springer, New York

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Routledge , New York

Curioso WH, Galan-Rodas E (2020) El rol de la telesalud en la lucha contra el COVID-19 y la evolución del marco normativo peruano. Acta Med Peru 37(3):366–375. https://doi.org/10.35663/amp.2020.373.1004

Datta H, Ailawadi KL, Van Heerde HJ (2017) How well does consumer-based brand equity align with sales-based brand equity and marketing-mix response? J Marketing 81(3):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0340

de Matos CA, Rossi CAV (2008) Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: a meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators. J Acad Market Sci 36(4):578–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0121-1

Keyser de A, Lemon K, Keiningham T, Klaus P (2015) A framework for understanding and managing the customer experience. MSI Working Paper No. 15–121, Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge

de Lima MM, Mainardes EW, Rodrigues RG (2020) Tourist expectations and perception of service providers: a Brazilian perspective. Serv Bus 14:131–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-019-00406-4

Dodds WB, Monroe KB, Grewal D (1991) Effect of price, brand, and store information on buyer’s product evaluations. J Marketing Res 28(3):307–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172866

Douglas SP, Craig CS (2007) Collaborative and iterative translation: an alternative approach to back translation. J Inter Market 15(1):30–43. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.1.030

Erkut S, Alarcón O, Coll C, Tropp LR, García H (1999) The dual-focus approach to creating bilingual measures. J Cross Cult Psychol 30(2):206–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022199030002004

Esch FR, Langner T, Schmitt BH, Geus P (2006) Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. J Prod Brand Manag 15(2):98–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610658938

Ferns BH, Walls A (2012) Enduring travel involvement, destination brand equity, and travelers’ visit intentions: a structural model analysis. J Destin Mark Manage 1(1/2):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.07.002

Flores-Hernández JA, Cambra-Fierro JJ, Vázquez-Carrasco R (2020) Sustainability, brand image, reputation and financial value: manager perceptions in an emerging economy context. Sustain Dev. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2047

Fombrun C, Shanley M (1990) What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad Manage J 33(2):233–258. https://doi.org/10.2307/256324

Fornell C, Cha J (1994) Partial least squares. In: Bagozzi RP (ed) Advanced methods of marketing research. Blackwell, Cambridge, pp 52–78

Fornell C, Larcker D (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Foroudi P (2019) Influence of brand signature, brand awareness, brand attitude, brand reputation on hotel industry’s brand performance. Int J Hosp Manag 76:271–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.05.016

Frías DM, Sabiote CM, Martín JD, Beerli A (2018) The effect of cultural intelligence on consumer-based destination brand equity. Ann Tourism Res 72:22–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.05.009

Fuentes-Blasco M, Moliner-Velázquez B, Servera-Francés D, Gil-Saura I (2017) Role of marketing and technological innovation on store equity, satisfaction and word-of-mouth in retailing. J Prod Brand Manag 26(6):650–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2016-1279

Gelbrich K (2011) I have paid less than you! the emotional and behavioral consequences of advantaged price inequality. J Retailing 87(2):207–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.03.003

Golinelli D, Boetto E, Carullo G, Nuzzolese A, Landini M (2020) Adoption of digital technologies in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of early scientific literature. J Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/22280

Gómez M, Lopez C, Molina A (2015) A model of tourism destination brand equity: the case of wine tourism destinations in Spain. Tour Manag 51:210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.019

Gustafsson A, Johnson MD, Roos I (2005) The effects of customer satisfaction, relationship commitment dimensions, and triggers on customer retention. J Marketing 69(4):210–218. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.210

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Harrigan P, Evers U, Miles M, Daly T (2017) Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tour Manag 59:597–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.015

Hau LN (2019) The role of customer operant resources in health care value creation. Serv Bus 13:457–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-00391-0

Heinonen K, Strandvik T, Mickelsson KJ, Edvardsson B, Sundström E, Andersson P (2010) A customer-dominant logic of service. J Serv Manag 21(4):531–548

Helkkula A, Kelleher C (2010) Circularity of customer service experience and customer perceived value. J Cust Behav 9(1):37–53. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539210X497611

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) Advances in international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Market Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hernández-Ortega B, Franco JL (2019) Developing a new conceptual framework for experience and value creation. Serv Bus 13:225–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-0379-4

Herstein R, Drori N, Berger R, Barnes BR (2017) Exploring the gap between policy and practice in private branding strategy management in an emerging market. Int Mark Rev 34(4):559–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-05-2014-0188

Hoeffler S, Keller KL (2003) The marketing advantages of strong brands. J Brand Manag 10(6):421–445. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540139

Hofstede, G (2021) Hofstede insights. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/. Accessed 25 Apr 2021

Hollenbeck B (2018) Online reputation mechanisms and the decreasing value of chain affiliation. J Marketing Res 55(5):636–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718802844

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huerta-Álvarez R, Cambra-Fierro J, Fuentes-Blasco M (2020) The interplay between social media communication, brand equity and brand engagement in tourist destinations: an analysis in an emerging economy. J Dest Mark Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100413

Hunter-Jones P, Line N, Zhang J, Malthouse E, Witell L, Hollis B (2020) Visioning a hospitality-oriented patient experience (HOPE) framework in health care. J Serv Manage. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0334

Hur WM, Kim H, Woo J (2014) How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. J Bus Ethics 125(1):75–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1910-0

Janney JJ, Gove S (2011) Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. J Manage Stud 48(7):1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00984.x

Kandampully J, Zhang TC, Jaakkola E (2018) Customer experience management in hospitality. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 30(1):21–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0549

Keillor BD, Lewison D, Hult GT, Hauser W (2007) The service encounter in a multinational context. J Serv Mark 21(6):451–461. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040710818930

Keiningham T, Ball J, Benoit S, Bruce HL, Buoye A, Dzenkovska J, Zaki M (2017) The interplay of customer experience and commitment. J Serv Mark 31(2):148–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-09-2016-0337

Keller KL (1993) Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J Marketing 57(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252054

Keller KL (2003) Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Prentice Hall, Hoboken

Khan I, Fatma M (2017) Antecedents and outcomes of brand experience: an empirical study. J Brand Manag 24(5):439–452. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0040-x

Khosravizadeh O, Vatankhah S, Baghian N, Shahsavari S, Ghaemmohamadi MS, Ahadinezhad B (2020) The branding process for healthcare centers: operational strategies from consumer’s identification to market development. J Healthc Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1723881

Kim SH, Lee S (2017) Promoting customers’ involvement with service brands: evidence from coffee shop customers. J Serv Mark 31(7):733–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-03-2016-0133

Kim KH, Park DB (2017) Relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: community-based ecotourism in Korea. J Travel Tour Mark 34(2):171–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1156609

Kim DY, Kim SB, Kim KJ (2019) Building corporate reputation, overcoming consumer skepticism, and establishing trust: choosing the right message types and social causes in the restaurant industry. Serv Bus 13:363–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-0386-5

Kock N, Lynn G (2012) Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: an illustration and recommendations. J Assoc Inf Syst Online 13(7):546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

Kok WK, Fon SO (2014) Shopper perception and loyalty: a stochastic approach to modeling shopping mall behavior. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 42(7):626–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2012-0100

Krystallis A, Chrysochou P (2014) The effects of service brand dimensions on brand loyalty. J Retail Consum Serv 21(2):139–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.07.009

Kumar J, Nayak J (2018) Brand community relationships transitioning into brand relationships: mediating and moderating mechanisms. J Retail Consum Serv 45:65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.08.007

Kumar V, Dalla Pozza I, Ganesh J (2013) Revisiting the satisfaction–loyalty relationship: empirical generalizations and directions for future research. J Retailing 89(3):246–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2013.02.001

Lallement J, Dejean S, Euzéby F, Martinez C (2020) The interaction between reputation and information search: evidence of information avoidance and confirmation bias. J Retail Consum Serv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.03.014

Lee D (2019) Effects of key value co-creation elements in the healthcare system: focusing on technology applications. Serv Bus 13:389–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-00388-9

Lee S, Lee D (2020) Healthcare wearable devices: an analysis of key factors for continuous use intention. Serv Bus 14:503–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-020-00428-3

Leone RP, Rao VR, Keller KL, Luo AM, McAlister L, Srivastava R (2006) Linking brand equity to customer equity. J Serv Res 9(2):125–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670506293563

López-Pérez M, Melero I, Sese FJ (2017) Does specific CSR training for managers impact shareholder value? Implications for education in sustainable development. Corp Soc Responsibil Environ Manag 24(5):435–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1418

Martínez P, Rodríguez del Bosque I (2016) The role of consumer identification on the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behaviour in the Spanish hotel industry. J Tour Anal 22(2):12–27

Meesala A, Paul J (2018) Service quality, consumer satisfaction and loyalty in hospitals: thinking for the future. J Retail Consum Serv 40:261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.011

Moliner-Velázquez B, Fuentes-Blasco M, Servera-Francés D, Gil-Saura I (2019) From retail innovation and image to loyalty: moderating effects of product type. Serv Bus 13:199–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-0378-5

Nassar MA (2017) Customer satisfaction and hotel brand equity: a structural equation modelling study. J Hosp Manage Tourism 5(4):144–162. https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2169/2017.08.002

Neslin S, Grewal D, Leghorn R, Shankar V, Teerling M, Thomas J, Verhoef P (2006) Challenges and opportunities in multichannel customer management. Serv Res 9(2):95–112

Nesset E, Nervik B, Helgesen Ø (2011) Satisfaction and image as mediators of store loyalty drivers in grocery retailing. Int Rev Retail Distrib Consum Res 21(3):267–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2011.588716

Netemeyer RG, Krishnan B, Pullig C, Wang G, Yagci M, Dean D, Wirth F (2004) Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. J Bus Res 57(2):209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00303-4

Obilo O, Chefor E, Saleh A (2020) Revisiting the consumer brand engagement concept. J Bus Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.023

Olavarría-Jaraba A, Cambra-Fierro JJ, Centeno E, Vázquez-Carrasco R (2018) Analyzing relationship quality and its contribution to consumer relationship proneness. Serv Bus 12:641–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-0362-0

Ostrom E (1991) Rational choice theory and institutional analysis: toward complementarity. Am Polit Sci Rev 85(1):237–243. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962889

Ostrom A, Parasuraman A, Bowen DE, Patrício L, Voss A (2015) Service research priorities in a rapidly changing context. J Serv Res 18(2):127–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515576315

Pansari A, Kumar V (2017) Customer engagement: the construct, antecedents, and consequences. J Acad Market Sci 45:294–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0485-6

Pappu R, Quester PG, Cooksey RW (2005) Consumer-based brand equity: improving the measurement–empirical evidence. J Prod Brand Manag 14(3):143–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420510601012

Podsakoff PM, Organ DW (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manage 12:69–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prentice C, Nguyen M (2020) Engaging and retaining customers with AI and employee service. J Retail Consum Serv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102186

Punyatoya P (2019) Effects of cognitive and affective trust on online customer behavior. Mark Intell Plan 37(1):80–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-02-2018-0058

Putnam R (1993) The prosperous community. Am Prospect 4(13):35–42

Putnam R (2000) Bowling alone. Simon and Schuster, New York

Radojevic T, Stanisic N, Stanic N (2015) Ensuring positive feedback: factors that influence customer satisfaction in the contemporary hospitality industry. Tour Manag 51:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.04.002

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3, SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt

Roberts PW, Dowling GR (2002) Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strateg Manag J 23(12):1077–1093. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.274

Roldán JL, Sánchez-Franco MJ (2012) Variance-based structural equation modeling. Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems. IGI Global, Pennsylvania, pp 193–221

Sarstedt M, Hair JF Jr, Cheah JH, Becker JM, Ringle CM (2019) How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas Market J 27(3):197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.05.003

Sen S, Cowley J (2013) The relevance of stakeholder theory and social capital theory in the context of CSR in SMEs: an Australian perspective. J Bus Ethics 118(2):413–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1598-6

Shankar V, Smith AK, Rangaswamy A (2003) Customer satisfaction and loyalty in online and offline environments. Int J Res Mark 20(2):153–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(03)00016-8

Sprott D, Czellar S, Spangenberg E (2009) The importance of a general measure of brand engagement on market behavior: development and validation of a scale. J Mark Res 46(1):92–104. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.46.1.92

Srivastava M, Kaul D (2014) Social interaction, convenience and customer satisfaction: the mediating effect of customer experience. J Retail Consum Serv 21(6):1028–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.04.007

Stein A, Ramaseshan B (2020) The customer experience – loyalty link: moderating role of motivation orientation. J Serv Manage 31(1):51–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-04-2019-0113

Su L, Swanson SR, Chinchanachokchai S, Hsu MK, Chen X (2016) Reputation and intentions: the role of satisfaction, identification, and commitment. J Bus Res 69(9):3261–3269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.023

Sürücü Ö, Öztürk Y, Okumus F, Bilgihan A (2019) Brand awareness, image, physical quality and employee behavior as building blocks of customer-based brand equity: consequences in the hotel context. Hosp Tour Manag 40:114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.07.002

The World Bank (2019) Peru indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/country/peru. Accessed 11 Jun 2020

Tournois L (2015) Does the value manufacturers (brands) create translate into enhanced reputation? A multi-sector examination of the value–satisfaction–loyalty–reputation chain. J Retail Consum Serv 26:83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.05.010

Traiki TAB, AlShammari SA, AlAli MN, Aljomah NA, Alhassan NS, Alkhayal KA, Al-Obeed OA, Zubaidi AM (2020) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patient satisfaction and surgical outcomes: a retrospective and cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg 58:14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.08.020

Umasuthan H, Park OJ, Ryu JH (2017) Influence of empathy on hotel guests’ emotional service experience. J Serv Mark 31(6):618–635. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-06-2016-0220

van Doorn J, Lemon KN, Mittal V, Nass S, Pick D, Pirner P, Verhoef PC (2010) Customer engagement behavior: theoretical foundations and research directions. J Serv Res 13(3):253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599

Veloutsou C (2007) Identifying the dimensions of the product-brand and consumer relationship. J Mark Manag 23(1/2):7–26. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725707X177892

Verhoef PC, Lemon KN, Parasuraman A, Roggeveen A, Tsiros M, Schlesinger LA (2009) Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J Retailing 85(1):31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.11.001

Wagner T, Lutz RJ, Weitz BA (2009) Corporate hypocrisy: overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J Marketing 73(6):77–91. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.77

Walker K (2010) A systematic review of the corporate reputation literature: definition, measurement, and theory. Corp Reput Rev 12(4):357–387. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2009.26

Walsh G, Beatty SE (2007) Customer-based corporate reputation of a service firm: scale development and validation. J Acad Market Sci 35(1):127–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0015-7

Wong PPW, Teoh K (2015) The influence of destination competitiveness on customer-based brand equity. J Dest Mark Manag 4:206–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.05.001

Yang X, Mao H, Peracchio L (2012) It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s how you play the game? The role of process and outcome in experience consumption. J Mark Res 49(6):954–966

Yani-de-Soriano M, Hanel PH, Vazquez-Carrasco R, Cambra-Fierro J, Wilson A, Centeno E (2019) Investigating the role of customers’ perceptions of employee effort and justice in service recovery: a cross-cultural perspective. Eur J Mark 53(4):708–735. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2017-0570

Yoo B, Donthu N (2001) Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J Bus Res 52:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00098-3

Yoo B, Donthu N, Lee S (2000) An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J Acad Market Sci 28(2):195–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282002

Zeithaml VA (1988) Consumer perception of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Marketing 52(3):2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

Funding

This work was supported by SEJ-601 “Innovación y Marketing para un Entorno Global Sostenible (IMEGS)”. Jesús Cambra-Fierro acknowledges the financial support from the following sources: I + D + i (Grant No ECO2017-83933-P) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and Generés research project (S09) from the European Social Fund and Gobierno de Aragón.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cambra-Fierro, J.J., Fuentes-Blasco, M., Huerta-Álvarez, R. et al. Customer-based brand equity and customer engagement in experiential services: insights from an emerging economy. Serv Bus 15, 467–491 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-021-00448-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-021-00448-7