Abstract

We conducted a systematic review of the available peer-reviewed literature that specifically focuses on the combination of sustainability and gender. We analyzed the existing peer-reviewed research regarding the extent to which gender plays a role in the empirical literature, how this is methodologically collected and what understanding of gender is applied in those articles. Our aim is to provide an overview of the current most common fields of research and thus show in which areas gender is already being included in the sustainability sciences and to what extent and in which areas this inclusion has not yet taken place or has only taken place to a limited extent. We identified 1054 papers that matched our criteria and conducted research on at least one sustainable development goal and gender research. Within these papers (i), the overall number of countries where lead authors were located was very high (91 countries). While the majority of lead authors were located in the Global North, less than a third of the articles were led by authors located in the Global South. Furthermore, gender is often just used as a category of empirical analysis rather than a research focus. We were able to identify (ii) a lack in coherent framing of relevant terms. Often no definition of sustainability was given, and only the sustainability goals (SDGs or MDGs) were used as a framework to refer to sustainability. Both gender and sustainability were often used as key words without being specifically addressed. Concerning the knowledge types of sustainability, our expectation that system knowledge dominates the literature was confirmed. While a problem orientation dominates much of the discourse, only a few papers focus on normative or transformative knowledge. (iii) Furthermore, the investigated literature was mainly contributing to few SDGs, with SDG 5 ‘Gender Equality’ accounting for 83% of all contributions, followed by SDG 8 ‘Decent Work and Economic Growth’ (21%), SDG 3 ‘Good Health and Well-being’ (15%) and SDG 4 ‘Quality Education’ (12%). We were additionally able to identify seven research clusters in the landscape of gender in sustainability science. (iv) A broad range of diverse methods was utilized that allow us to approximate different forms of knowledge. Yet within different research clusters, the spectrum of methodologies is rather homogeneous. (v) Overall, in most papers gender is conceptualized in binary terms. In most cases, the research is explicitly about women, running the risk that gender research in sustainability sciences grows into a synonym for women's studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The progression of climate change and further environmental degradation have direct ecological and social consequences that affect and will affect people differently according to different structures of social inequality (Kaijser and Kronsell 2014; Johnson et al. 2022; Thompson-Hall et al. 2016). This insight is important insofar as it sheds light on the fact that environmental problems and climate change will not have the same effects globally, but are context specific and related to power and domination structures (see contextualized vulnerability O’Brien et al. 2007) and must therefore be analyzed accordingly (Hackfort 2015; Johnson et al. 2022). However, sustainability science is not only dedicated to analyzing the problems that we will face as a result of ecological exploitation in ecological, social and economic terms, but also attempts to develop solution-oriented strategies and provide policy advice (von Wehrden et al. 2017). Therefore, it is equally important to reflect this power and domination-critical perspective in the search for solution options and to include different stakeholders (Malin and Ryder 2018). One specific issue that should be analyzed in connection with sustainability science problems and solution development is gender. As many studies have already shown, the effects of climate change and other problems resulting from the exploitation of natural resources have a gender-specific (Dankelman 2010; Denton 2002; MacGregor 2010) or intersectional impact (Kaijser and Kronsell 2014; Johnson et al. 2022; Thompson-Hall et al. 2016). Even though the unequal impacts of, e.g., climate change in terms of gender have been researched empirically in many areas such as agriculture (Agarwal 1998; Alston and Whittenbury 2013; Glazebrook et al. 2020), migration (Chindarkar 2012; Lama et al. 2021) and natural disasters (Enarson and Chakrabarty 2009; Neumayer and Plümper 2007), to date there has been no systematic recording of the research field of gender in the sustainability sciences. Our focus in this review is to give a broad overview of the current state of art regarding the topic of gender in sustainability science. We analyze the existing research regarding the extent to which gender plays a role in the empirical literature, how this is methodologically collected and what understanding of gender is applied in those articles. Our aim is to provide an overview of the currently most common fields of research and thus show in which areas gender is already being included in the sustainability sciences and to what extent and in which areas this inclusion has not yet taken place or has only taken place to a limited extent. Before describing our research focus in more detail, we first define our two main concepts, namely sustainability and gender.

We refer to sustainability based on the widely quoted definition by the Brundtland report from 1987 as meeting present needs without compromising the ability to compromise the needs of future generations (Brundtland 1987). Furthermore, our sustainability understanding includes an integrational perspective, also referred to as nested circles model, meaning that sustainability builds on economic, social and ecological dimensions that are interdependent and interconnected (Lozano 2008; Odrowaz-Coates 2021). In this framework in opposition to others, the economic and social pillars are not independent from the environmental dimension, but instead depend on it (Mebratu 1998).

Sustainability science addresses the challenges that threaten the long-term security of societal development conditions by distinguishing three levels that need to be researched: the systemic level to create system knowledge, the normative level to map out target knowledge and the operative level that aims to develop transformative knowledge (Brandt et al. 2013; Grunwald 2007; Michelsen and Adomßent 2014). System knowledge aims at describing and understanding a given social and/or ecological system via descriptive analysis. This often is disciplinary empirical research to analyze the dynamics, root causes and underlying mechanisms of the identified problem or system. System knowledge tries to reflect the current state of a system and its ability to change (Brandt et al. 2013; Grunwald 2007; von Wehrden et al. 2017; Wiek and Lang 2016). After identifying a problem and being able to describe it, target or normative knowledge is important to indicate the perception and direction of change. By asking what a desirable future situation could look like, target knowledge provides an orientation and an aim toward the development of solution options. This knowledge is normative since it asks which values are important when developing solutions to the identified problem (Grunwald 2007; von Wehrden et al. 2017). To then be able to address real-world place-based problems, transformative or action-oriented knowledge is necessary. By developing evidence-supported solutions, transformative knowledge offers possible transition paths from the current to the desirable situation (Grunwald 2007; von Wehrden et al. 2017; Wiek and Lang 2016). This action-oriented knowledge which aims at solving and mitigating the identified context-specific problem represents the main gap to this day (von Wehrden et al. 2017). While there are diverse and multi-faceted approaches in sustainability science (Clark and Harley 2019), we use the sustainable development goals as a lens of analysis. We agree that the conceptual foundation of sustainability is very diverse, and have mentioned the root literature above. However, the sustainable development goals can be seen as a main policy basis that currently attempts to shift the world toward a more sustainable development. While we agree that many conceptual foundations exist to this end, we focus on the SDGs since these contain a diversity of topical focuses, including gender.

Within the domain of sustainability, this review focuses on the diverse scientific literature published under the term of ‘gender’. We refer to gender as a historical construct consisting of attributes, norms, roles, opportunities, responsibilities and expectations that are socially, culturally and institutionally embedded and produce certain gender identities and social constructs (Arevalo 2020; Lieu et al. 2020; Mechlenborg and Gram-Hanssen 2020). Consequently, gender is not ‘given’ but learned and therefore dynamic and changing across a diverse and fluid spectrum (Curth and Evans 2011; Moyo and Dhliwayo 2019). Furthermore, we acknowledge the ‘intersectional’ nature of gender, i.e., the idea that one’s gendered experience of life overlaps and interacts with other axes of identity and systems of oppression (Richardson 2015).

Gender and environment

Now that we have defined the two core concepts of this article, sustainability and gender, we proceed to briefly summarize the state of research on gender in environmental and sustainability sciences. Before sustainability was declared a central part of international development in the 1990s and gender issues were incorporated in those development frameworks from the early 2000s, activists and researchers drew attention to the links between environmental degradation and gender inequality as early as the 1970s, with a particular focus on the disadvantages faced by women (Levy 1992; Mehta 2016). This early field of research called ecofeminism postulated an intrinsic relationship between women and nature based on their shared reproductive capacity (Majumdar 2019). Ecofeminism unites many currents and movements. Some of these take up an essentialist and biologistic understanding of gender, e.g., Shiva (1988), Mies and Shiva (1995), Agarwal (1992), Hackfort (2015). Women are understood as caring and nurturing by nature and at the same time suppressed by patriarchy as always being inferior and dominated by men (Agarwal 1992). Ecofeminists identified that the exploitation of women as well as of nature occurs in similar patterns, which is why it was assumed that "all women would have the same kind of sympathies and understandings of environmental change as a consequence of their close connection to nature [as well as their shared experience in exploitation]" (Majumdar 2019, p. 72). Politically, these arguments and claims were taken up by the Women in Development (WID) approach which was adopted by many development agencies and NGOs in the 1970s. They argued that because of women's unique relationship with the environment as well as their particular affection by the effects of environmental degradation, women should receive special attention in global economic development (Levy 1992; Mehta 2016; Sasser 2018). Over the years, the arguments and theories of the essentialist view of ecofeminism outlined above have been widely criticized (e.g., Agarwal 1992). Many feminist researchers have pointed out that concepts of nature and gender are socially and historically constructed and not biologically determined (Agarwal 1992; Gottschlich et al. 2022; Levy 1992). Furthermore, the depiction of women as a unitary was declared insufficient, as gender must be considered and analyzed in combination with other forms of oppression such as race, class, caste and so on (Agarwal 1992; Häusler 1997; Levy 1992).

What is disputed, however, is not that the oppressive relationship between gender and nature exists, but how it is justified and how it should be responded to Gottschlich et al. (2022). One of the most recited critiques stems from the Indian economist Bina Agarwal (1992), who, instead of an essentialist derived connection between nature and gender, adopts a materialist perspective to describe the link between Indian women and the environment (Agarwal 1992; Gottschlich et al. 2022). Agarwal points out that a gendered and class-based organization of production, reproduction and distribution results in differential access to natural resources and ecological processes (Agarwal 1992). For example, women’s responsibility for certain natural resources is based on the gendered division of labor as well as class-specific ownership and property relations. This ascription can also be seen as dependence of women on these natural resources to make a living, which often entails a greater sensitivity to the respective ecological processes (Agarwal 1992; Gottschlich et al. 2022; Sasser 2018). Agarwal terms this research perspective ‘feminist environmentalism’ (Agarwal 1992). As a further development of feminist environmentalism, feminist political ecology (FPE) emerged in the 1990s, which takes a more holistic, intersectional perspective regarding gender on the connections between gender and nature (see for example Rocheleau et al. 1996; Gottschlich et al. 2022; Sasser 2018). FPE focuses explicitly on gender-specific power relations, which are considered in their historical, political and economic contexts, as well as across a range of scales (Gottschlich et al. 2022; Mehta 2016). Possible research foci include, for example, gender-specific access to natural resources and an intersectional and decolonial approach to environmental degradation and ecological change, as well as ecological conservation and sustainable development (Gottschlich et al. 2022; Mehta 2016; Sasser 2018). FPE questions the so far dominating victimizing narratives and stereotypes of women often from the Global South and emphasize instead their agency in, for example, highlighting their resistance practices and activism (MacGregor 2020). As research from feminist environmentalism and feminist political ecology has broadened the perspective on the connections between gender and the environment, new approaches have also been sought at the international political level. The focus and programs now shifted toward gender and development (GAD) which addresses all genders. GAD approaches also acknowledge socially constructed gender roles as the cause for gender inequality and aim at creating different forms of empowerment from a grassroots, bottom-up perspective that includes, for example, women as active participants in development from the beginning (Sasser 2018). The last concept which we want to highlight is queer ecology that was developed from the 2010s onward, e.g., Mortimer-Sandilands and Erickson (2010). Queer ecology analyzes and critically reflects the dominant human–environment relationships in terms of the underlying heteronormative order of the gender binary. The queer perspective expands feminist political ecology by deconstructing the 'naturalness' of heterosexual desire and the associated heteronormative relations of reproduction and production. The queer theoretical perspective questions the heterosexual nuclear family as the basic economic unit of the household and instead expands the view of social re-production by focusing on queer care relationships (Bauhardt 2022; Hofmeister et al. 2012).

Gender and sustainability

Research integrating gender as well as insights and theories from gender studies into sustainability science is relatively new and as we will see is not yet an established cornerstone in this research field. Nevertheless, scholars so far have already presented some important aspects as to why and how gendered perspectives should be integrated into sustainability science. Both gender studies and sustainability science are inherently normative sciences. They aim both at system knowledge about existing inequalities and unsustainable structures and their causes, but at the same time also gaining transformational knowledge about how inequalities can be reduced and resolved to create a more just world (Hofmeister et al. 2012). Both research fields position themselves as inter- and transdisciplinary and furthermore conduct their research across different scales, spatial as well as temporal (Bürkner 2012; Jerneck et al. 2011; Martens 2006; Rodenberg 2009). Feminist analyses and the integration of gender into sustainability science can however help integrate social and historical contexts more comprehensively in the analysis of socio-ecological systems as well as contribute to the development of suitable policy instruments for reducing gender inequalities and expanding adaptive capacities by contributing a social science perspective (Hackfort 2015; Hofmeister et al. 2012; Littig 2002). Feminist scholarship especially enhances sustainability science research by including analysis of power relations. Research interests within sustainability science should uncover the prevalent power relations in nature–society relationships and deconstruct them at various levels (Hackfort 2015; Hofmeister et al. 2012). Furthermore, feminist analysis critiques the claims of objective, universal and (gender) neutral scientific research and instead emphasizes the generation of situated knowledge that adopts partial perspectives which cannot be understood in isolation from its context (Hofmeister et al. 2012).

While the concept of gender is already explored within some research areas of sustainability science literature (Eger et al. 2022; Khalikova et al. 2021; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2014), the current state of the art remains widely unclear (Gottschlich et al. 2022; Hackfort 2015).

Research interests

Thus, in this paper, we explore the heterogeneous research area of gender in sustainability science by means of a systematic literature review of the peer-reviewed literature to identify prevalent research foci, trends and gaps. We focus on five research interests outlined in the following.

Bibliometric indicators

Firstly, we create a bibliometric overview of the scientific literature on gender in sustainability, thereby giving an account of the geographic origins, contexts and affiliations of authors as well as geographic tendencies concerning both authorships and study locations. Moreover, we closely examine definitions and perceptions of gender within the given research. Here, we differentiate between two applications: (1) gender as a specific empirical category and (2) gender as the general research topic. We focus on analyzing whether articles use gender as one of several variables in their empirical research or focus on gender as a central research topic. Our aim here is to examine whether research to date has addressed gender in a rather superficial way or whether and in which cases deeper analyses of gender and sustainability are taking place.

Sustainability definitions

Our second research interest centers around specific definitions of sustainability, which we acknowledge to be diverse and often incoherent within the available literature. We examine which sustainability concepts are predominantly used in the reviewed articles as well as if and how sustainability is defined. By identifying the diverse understandings of sustainability within gender research, we explore the different ways that specific concepts of sustainability and gender are intertwined. In addition, we link these notions to the three knowledge types we described above, system, target and transformative knowledge. These different types of knowledge are all important when conducting transdisciplinary research as is done in sustainability science (Wiek and Lang 2016). They all fulfill important steps when approaching wicked problems such as climate change or gender equality and build the basis for a comprehensive understanding which is needed when dealing with multifaceted and complex problems (von Wehrden et al. 2017). Our research interest is to analyze what kind of knowledge there is already in regard to gender in sustainability science and to present a state of the art which knowledge types are prevalent and which need more attention in the future. To this end, we assume that systemic, descriptive knowledge (Brandt et al. 2013; CASS et al. 1997) is decreasing over time, yet still expect to find overall less papers creating target or transformative knowledge.

Sustainable development goals and gender equality

Thirdly, we focus our scope of research on articles linked to at least one of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) (United Nations 2015). Building on and extending the Millennium Development Goals, the SDGs provide an umbrella of sectors which the examined research articles can be attributed to and/or associate themselves with. The SDGs were agreed on by the United Nations as “a comprehensive, far-reaching and people-centered set of universal and transformative Goals and targets” (United Nations 2015). Applying the lens of the SDGs allows us to narrow down the range of articles related to sustainability, while acknowledging they do not provide an ultimate, but a prominent framework. In view of the SDGs as forming an entity of interlinked targets which are aimed at fostering simultaneous, overarching developments (Toth et al. 2022), we want to find out whether the papers are equally distributed to the SDGs or whether a few SDGs are dominating the discourse. This approach makes it possible to compare the number of research articles on gender associated with individual goals as well as to highlight clusters of SDGs which are prevalently mentioned together. By deriving research areas which are represented in a smaller share, we identify possible future areas to focus on.

Methods

In the fourth research interest, we concentrate on the methods used in the reviewed articles. Research within gender studies and feminist research are dominated by qualitative methods. Many scholars investigate their research interests regarding gender and gender equality by applying qualitative methods which document the subjects’ experiences and perspectives in their own terms (Gaybor 2022; Harcourt and Argüello Calle 2022). We determine clusters of methods used and how these connect to the knowledge types of sustainability and also to the respective SDGs that each article targets. Based on that, we are able to specify certain research clusters which can be grouped according to their generated knowledge and applied methods as well as thematic focus. This gives us information about which methods dominate in which research fields, to what extent they differ and which methods have not been used much to date.

Definition and understanding of gender

Finally, we aim to draw conclusions on definitions and understandings of gender in sustainability science and how these have changed over time. There cannot be a general historical account of the understanding of gender as it must always be specific to societies, cultures and regions of the world. For instance, the Western academic understanding of gender has undergone certain fundamental changes in the past century (Haig 2004; Muehlenhard and Peterson 2011). In this paper, we focus on two changes, namely (i) the constructivist turn which conceptualizes gender as not biologically determined in a binary of man and woman, but instead socially constructed (Fenstermaker 2013; West and Zimmerman 1987) and (ii) the acknowledgment of the ‘intersectional’ nature of gender (Bürkner 2012), i.e., the idea that one’s gendered experience of life overlaps and interacts with other axes of identity and systems of oppression (Crenshaw 1989; Richardson 2015). We explore if these important developments in the understanding of gender are reflected in the temporal distribution of the reviewed literature. Moreover, we detect correlations between (non-)binary, (non-)intersectional understandings of gender and research clusters/fields of sustainability.

In this review, we attempt to systematize a complex and heterogeneous field of research, which is why we are aware that this aim entails the risk of uncovering inconsistencies, renewing them or even creating them. We do not claim that our research interests and choice of methods are the ‘correct’ ones to systematically assess the topic of gender in sustainability science, but rather to provide an overview of which topics and methods have dominated the field of research to date, how these can be located in light of sustainability science concepts such as knowledge types or the SDGs as well as how individual international contributions can be used constructively for the further development of the subject area.

The paper is organized as follows. In section two, we describe the methods used, followed by the presentation of our results in section three. In section four, we discuss these results and give an account of their methodological limitations. Finally, we conclude by reflecting upon the results of this review and postulate future research implications.

Methods

Our systematic literature review was based on a quantitative bibliometric content analysis of the available literature. We thus created a broad overview of the state of the literature, with a particular focus on the key interests named in the introduction.

We identified articles via the Scopus database (Elsevier B.V 2020). Scopus was chosen as it contains natural science as well as social science articles. Additionally, Scopus allows for the search and preview of abstracts, which was helpful for conducting the systematic review.

We applied a search string containing the two words ‘gender AND sustainab*’. The initial search resulted in 5993 papers for the period of 1991–2021. We restricted our search to this time period because hardly any literature was available before, and most journals have no online record before. We excluded books, conference papers and book chapters and limited the review to articles that were published in English.

Inductively we created the following criteria: the included articles must

-

(i)

be able to be assigned to at least one SDG and

-

(ii)

have gender as a research focus, and not only as a category of analysis.

Since the review focuses on gender in sustainability science, we needed at least two criteria for the inclusion of the articles. For one, the paper should make a clear link to sustainability, since this term is often used as a buzzword and we tried to exclude any literature that mentioned the concept only vaguely or in passing, such as in the first part of the introduction of the latter parts of the discussion. Regarding the first exclusion criteria, we decided to use the SDGs as one possible framework that reflects our understanding of sustainability science topics, and that can be seen as the current policy baseline. For our analysis, this meant in practical terms that we checked whether the topic of an article could be assigned to at least one SDG and, if so, which one. The extent to which the article addresses the SDGs themselves did not play a role here.

The second criterion to include a paper in the full-text analysis refers to the realization of gender. When conducting a pre-test with a random sample of articles, we realized that many articles just used gender as one of many variables in their empirical research and that the focus of the research question lay upon something completely different, where gender was a mere building block or one of many variables. To be able to narrow down our sample, we decided to only include articles that focus on gender as a central research interest. Therefore, we always read the respective abstracts to be able to determine whether a thorough research focus on gender was given or not.

Based on these criteria, we excluded 4959 articles. The remaining 1054 papers were coded according to the following five questions:

-

(i)

Does the article create system knowledge, target knowledge and/or transformative knowledge? The definitions for the three individual types of knowledge were extracted and applied from various articles, as already detailed in the introduction (see: Brandt et al. 2013; Grunwald 2007; Michelsen and Adomßent 2014).

-

(ii)

Which SDGs can be assigned to the article? Which sustainability concepts and definitions were named?

-

(iii)

Which methods were used in the article? We inductively grouped the respective methods into categories.

-

(iv)

Does the article conceptualize gender as binary, as non-binary and/or as social constructs?

-

(v)

Does the article consider gender as the only category of analysis? Were further social categories addressed as well or is there an intersectional approach? Other social categories were specified in such cases.

A team of seven coders worked on the literature review in an iterative process. We coded the papers separately as well as together and clarified possible pitfalls in the criteria to minimize ambiguities. The respective categories were then summarized in a table which was the basis of all statistical analysis of the content.

Furthermore, we are interested in investigating whether there are specific research clusters within the domain of gender in sustainability science. Our aim is to identify the dominant fields of research that deal with gender and sustainability and to characterize these in more detail on the basis of the above-mentioned research interests. To derive groups out of the reviewed papers, we used a linguistic approach that classifies all papers into groups based on their word abundance. Within this analysis, we compiled all words in a document containing all papers, and the respective x–y table was clustered into groups according to Ward (1963). To visualize the respective groups, we used a detrended correspondence analysis (Abson et al. 2014), which allows for a descriptive analysis of the linguistic patterns of the literature. The groups were illustrated by significant indicator words that we identified by an indicator species analysis. Based on this multivariate linguistic approach, we derived seven unbiased groups of the reviewed literature, which are solemnly based on the word abundance of the papers. All statistical analyses were conducted with the R Statistical Software (v4.2.2; R Core Team 2022).

Results

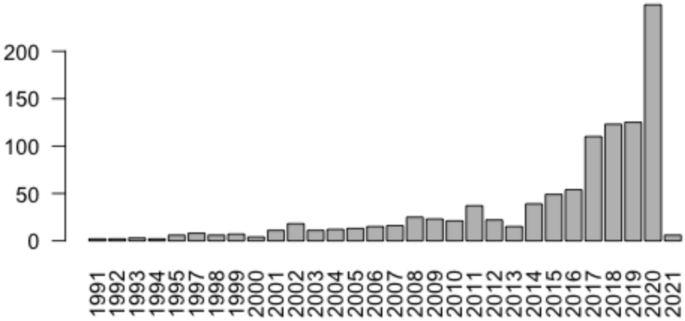

We identified a total of 1054 papers, out of which almost half were published after 2017 (48%) (Fig. 1).

While some journals contain a relatively high proportion of papers (e.g., Sustainability 65 articles, Gender and Development 31 articles, World Development 21 articles, Gender, Place and Culture 14 articles, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 14 articles), there is no dominating journal, and articles are published in a total of 566 journals. Lead authors originate mainly from the USA (19.9%), UK (11.5%), Australia (5.8%), Canada (4.6%), India (4.5%), South Africa (4.4%), Spain (4.3%) and Germany (4.2%). Lead authors from Sweden, Netherlands, Nigeria, Italy, China, Austria, Indonesia, South Korea, Denmark, Turkey, Norway and Switzerland published more than 1%, but less than 4% of the papers. All other countries have less than 1% of the lead authors in proportion (see online appendix 1). These numbers must be interpreted particularly in the aspect that only English articles were included in the analysis.

The vast majority of the papers (844) are empirical, and 113 papers utilize gender as a category within the empirical analysis. Roughly, a third of all the articles analyze gender in combination with other social categories. The most researched intersection is between gender and class (also specified as income differences), followed by the intersection between gender and race. Concerning the utilization of the SDGs, 83% of all papers research on Gender Equality (SDG 5). Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8) is included in 20% of all papers. Good Health and Well-being (SDG 3) and Quality Education (SDG 4) are mentioned by about 15% of all papers. All other SDGs are mentioned by less than 10% of the papers (Table 1).

The majority of concrete definitions regarding sustainability built on the SDGs (137); the Millennium Goals are mentioned by some 40 papers, the Brundtland report by 23, Agenda 21 by 16, while all other frameworks such as the Kyoto protocol (2), national strategies (2), Rio declaration (2), IPCC (1), the Three Pillar Framework (1), Corporate Sustainability (1) and Club of Rome (1) are mentioned less often. Concerning the knowledge types, system knowledge clearly dominates, with stronger ties to normative knowledge and slightly weaker ties to transformative knowledge. All three types of knowledge are only achieved by few (31) papers (Fig. 2).

Concerning the use of scientific methods, the most abundantly applied methods are literature reviews (22.5%), closely followed by interviews (22%). Statistical approaches are used by 12,7% of the papers, closely followed by methods of participatory research (10.4%), case study approaches (10.6%) and surveys (9.8%). Other methods are less abundantly used, including ethnographic approaches (3.6%), discourse or content analysis (2.7%) or systematic literature review (2.7%) (Fig. 3).

The majority of papers consider a binary gender understanding. While there was an increase in the absolute total number of papers that considered a socially constructed gender understanding overall, the proportion of papers falling into this category did decrease.

In the following section, we introduce the different groups derived from multivariate analysis, and present key characteristics of the individual groups (Fig. 4).

Cluster 1: gender equality and institutions

The first cluster, which contains 207 papers, emerged first in 1991 and is thus the oldest cluster. The proportion of articles displays a diverse activity, having peaked in 2020. The research focuses on the institutional commitment toward gender equality (Hennebry et al. 2019; Kalpazidou Schmidt et al. 2020; Larasatie et al. 2020). The topical focus encompasses entrepreneurship (Kamberidou 2020; Kravets et al. 2020; Vershinina et al. 2020), especially concerning the empowerment of women in social enterprises (Allen et al. 2019; Benítez et al. 2020; Green 2019), yet also research regarding peace building (Adjei 2019; Kim 2020; Turner 2020), foreign policy (Agius and Mundkur 2020; Cohn and Duncanson 2020) and security (Curth and Evans 2011; Mahadevia and Lathia 2019; Rothermel 2020) is conducted. These focal points are reflected in the usage of the most mentioned SDGs, 8 (decent work), 10 (reduced inequalities), and 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions). About one-quarter of the articles channel sustainability through SDGs and MDGs or the Brundtland report as well as the Agenda 21. The research questions of nearly all articles aim at generating system knowledge, yet more than half of them also create normative knowledge. Besides gender, half of the papers include other social categories in their analysis, mostly focusing on class, race, sexuality and ethnicity. A binary gender framing is mainly used, yet one-quarter of the articles acknowledge gender to be a social construct. Most of the papers are qualitative case studies utilizing interviews or ethnographic approaches.

Cluster 2: gender in health and well-being

The second cluster, consisting of 165 papers, emerged in 2003 and is closely related to the first and the 6th cluster. The topical focus of this cluster is on health equity and the impacts of gender on health services (Manandhar et al. 2018; Scheer et al. 2016; Thresia 2018), for instance concerning the evaluation or assessment of health programs (Friedson-Ridenour et al. 2019; Williams et al. 2009). Next to barrier identification (Kennedy et al. 2020; Sawade 2014; Sciortino 2020) and empowerment strategy assessment (Maluka et al. 2020; Plouffe et al. 2020; Yount et al. 2020), system knowledge is created through qualitative assessment strategies such as methods of participatory research and interviews. A considerable number of papers discussed health equity also in terms of motherhood, especially maternal health and maternal mortality rates were covered often (Klugman et al. 2019; Morgan et al. 2017). One-quarter of the articles reference sustainability through SDGs and MDGs. About one-third of the articles also apply other social categories in their analysis, mostly adding the concept of class but also ethnicity, race and religion. While the papers in this cluster widely build on a binary gender framework, many concern gender inequalities, especially aiming at low- and middle-income countries and communities.

Cluster 3: gendered access to resources

Cluster number three, which contains 244 papers, started to emerge in 1995, with the majority of papers being published between 2017 and 2020. According to the word abundance analysis, this cluster partly overlaps with cluster number two and six. On the one hand, the papers in this cluster focus on the assessment of inequalities and gender-specific barriers. Specifically, they examine the structural discrimination as well as underrepresentation of women in certain areas (Crockett and Cooper 2016; Ennaji 2016; Lama et al. 2017; Woodroffe 2015). Two areas that are analyzed most often are the limited access to specific natural resources respective institutions such as water (Andajani-Sutjahjo et al. 2015; Pandya and Shukla 2018; Singh and Singh 2015), energy (Burney et al. 2017), education (Ansong et al. 2018) and healthcare (Rivillas et al. 2018; Theobald et al. 2017). Secondly, the limited and ineffective opportunities to participate in decision-making processes, for example, in politics (Dyer 2018; Lama et al. 2017; Sindhuja and Murugan 2018), agriculture (Azanaw and Tassew 2017) and at the workplace (Limuwa and Synnevåg 2018; Rohe et al. 2018). The identification of different challenges which women face in regard to participation and representation clash with the fact that the women in these cases often bear the responsibility for survival and sustainability of the respective community (Belahsen et al. 2017; Garutsa and Nekhwevha 2016; Limuwa and Synnevåg 2018; Rohe et al. 2018). Apart from this problem-oriented focus creating system knowledge, quite many articles in this cluster offer evidence-based recommendations and solution strategies on how to improve those inequalities by suggesting possible areas of intervention such as enforcing legislation, mentorship, quotas, financial inclusion, etc. (Ansong et al. 2018; Appiah 2015; Burney et al. 2017; Mello and Schmink 2017; Saviano et al. 2017). The authors emphasize that adaptation strategies and policy-making must be gender sensitive and critically reflect gender-specific circumstances, vulnerabilities and experiences (Garai 2016; Rakib et al. 2017; Rivillas et al. 2018; Shanthi et al. 2017; Theobald et al. 2017). Some papers channel sustainability through SDGs and MDGs or the Brundtland report as well as the Agenda 21. About 50 papers focus on class or caste, race, ethnicity and religion as categories apart from gender. A binary gender framing is mostly used, and studies are predominantly qualitative case studies utilizing interviews, surveys or methods of participatory research.

Cluster 4: gender inequality in public infrastructure

Cluster four contains 191 papers with first publications in 1997 and the majority of the papers being published between 2017 and 2020. The thematic focus of this cluster lies upon gender inequality in public infrastructure. The articles mainly apply a problem-oriented lens while addressing different areas of gender discrimination in which safe, affordable and sustainable access to certain institutions of public infrastructure is not given. Three areas are analyzed most often: gendered mobility investigates gender differences in travel patterns and modal split (Abasahl et al. 2018; Winslott Hiselius et al. 2019; Kawgan-Kagan 2020; Le et al. 2019; Mitra and Nash 2019; Polk 2003), gendered barriers in public transportation (Al-Rashid et al. 2020; Malik et al. 2020; Montoya-Robledo and Escovar-Álvarez 2020) as well as gender discrimination within transport planning and policy-making (Kronsell et al. 2016, 2020; Wallhagen et al. 2018). The second area discusses gendered access to healthcare, mostly referring to services providing counseling and treatment for victims of gender-based violence (Betron et al. 2020; Minckas et al. 2020; Prego-Meleiro et al. 2020), sexual and reproductive health rights (Bosmans et al. 2008; Lince-Deroche et al. 2019; Loganathan et al. 2020) and HIV prevention as well as treatment (Gómez 2011; Ssewamala et al. 2019). The third area analyzes gendered access to education (Burridge et al. 2016; Islam and Siddiqui 2020). The majority of the papers create systemic knowledge. Notably, many papers are published in the journal ‘Sustainability’ and several articles contain ‘women’ in the papers’ title. A few articles reference sustainability by mentioning the SDGs and the Brundtland report. About 40 papers mention interlinkages with other types of social categories and do not solely focus on gender in their analysis. The gender framing is mostly binary. The methodology in this cluster utilizes most often literature reviews or case studies conducting interviews or surveys.

Cluster 5: gender inequalities in agricultural systems

This cluster consists of 102 papers, and dates back to 1995. Since 2017, its contribution is slowly increasing. The research within this cluster can be grouped into four aspects and widely generates system knowledge. The majority of the research focuses on gender roles and how these influence interactions with(in) local systems such as forestry (Benjamin et al. 2018; Nhem and Lee 2019; Stiem and Krause 2016), agriculture (Drafor et al. 2005; Ergas 2014; Fischer et al. 2017), fisheries (Tejeda and Townsend 2006; Szymkowiak and Rhodes-Reese 2020; Torell et al. 2019), water (Imburgia 2019; Singh 2006, 2008) and the energy sector (Buechler et al. 2020; Stock 2021; Wiese 2020). One topical focus is about participation of women in decision-making and planning processes (Ihalainen et al. 2020; Mulema et al. 2019; Pena et al. 2020). Another focus aims at gender differences in climate adaptation and conservation strategies (Abdelali-Martini et al. 2008; Rao et al. 2020; Wekesah et al. 2019). Furthermore, many papers investigate challenges women face in (agricultural) resource control and management (Badstue et al. 2020; Pehou et al. 2020) as well as in the access to markets and the distribution of land (Holden and Tilahun 2020; Meinzen-Dick et al. 1997). Lastly, a considerable number of papers discuss gendered climate vulnerabilities and risk management (Friedman et al. 2019; Yadav and Lal 2018; Ylipaa et al. 2019). These research interests are also reflected in the mentioned SDGs, which are 15 (life on land), 8 (decent work), 2 (zero hunger) and 1 (no poverty). Only very few papers channel sustainability through SDGs and MDGs. About one-third of the articles also include other social categories in their research, mostly adding the concept of class but also religion, age, race and ethnicity. Regarding the understanding of gender about 10% perceive gender to be a social and cultural construct and only one mentions a non-binary understanding of gender. The majority of the papers conduct qualitative case studies, often combined with interviews, surveys or methods of participatory research. Papers within this cluster mostly report about local projects conducted in low- and middle-income countries of the Global South.

Cluster 6: inclusion of gender equality in sustainable development

Cluster six contains 45 articles and emerged in 1992. The number of published papers within this cluster fluctuated widely over the years, yet since 2019 the proportional contribution is slowly increasing. In contrast to the other clusters, the papers in this group are not centered around a certain topic, but rather focus on a general discussion regarding the inclusion of gender issues in research on sustainable development, yet here scholars mainly apply problem-oriented empirical research on gender inequalities, discrimination and biases often on a national scale. Those gender inequalities are often referred to as gender gap and focus mostly on political representation (Azmi 2020; Kreile 2005; Purwanti et al. 2018; von Dach 2002), access to education (Assoumou-ella 2019; Cortina 2010; Cheng and Ghajarieh 2011; Suvarna et al. 2019) and participation in natural resource management (Sasaki and Chopin 2002; Valdivia and Gilles 2001; Yadav and Sharma 2017). These topical areas also overlap with the mentioned SDGs, 4 (quality education), 8 (decent work), 3 (good health and well-being) and 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions). Gender equality is thus highlighted as one of the most important tasks in sustainable development. A few articles reference sustainability by mentioning the SDGs and the Brundtland report. About 20% of the articles also add further social categories apart from gender when analyzing inequalities in sustainable development. Besides gender, most of these focus on race and class. While a mere half of the papers in this cluster are conceptual, the rest conduct mainly qualitative case studies utilizing interviews, surveys and methods of participatory research. Studies range across the global and the country or local level.

Cluster 7: gender diversity and corporate performance

The last cluster is a recently emerging research area with contributions starting from the year 2016 onward. The 44 contributions in this cluster focus on human resource characteristics, primarily the gender diversity of boards (Orazalin and Baydauletov 2020; Romano et al. 2020; Xie et al. 2020) and the sustainable performance of firms or other organizations (Burkhardt et al. 2020; Mungai et al. 2020; Ozordi et al. 2020). The cluster as such is very homogenous with many contributions sharing similarly phrased research questions and a local approach that is reflected in either the focus on organizations in a certain geographic region or of a specific economic sector. This is also reflected in the most often mentioned SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth). Nevertheless, two research angles can be differentiated within this cluster which both contribute to create system knowledge: one angle investigates the relationship between gender representation and indicators of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Tapver et al. 2020; Valls et al. 2020; Yarram and Adapa 2021), corporate environmental performance or specific sustainable policies (Birindelli et al. 2019; Elmagrhi et al. 2018; García Martín and Herrero 2020), while another more economic angle investigates the relationship between gender representation and the limitation of risks for ‘sustainable’ i.e., continuous growth (Gudjonsson et al. 2020; Loukil et al. 2019; Suciu et al. 2020). In their findings, most papers tend to highlight gender-(binary-)based differences in morality or ethics. There is no intersectional approach or other social categories in the articles, as well as nearly no sustainability references. The majority of the papers conducted quantitative research utilizing statistics.

Discussion

In the introduction, we set out five research interests for this systematic literature review. Based on the research clusters, we revisit these focal points and embed our findings into the current debate.

(i) Regarding bibliometric data, while the overall number of countries with lead authors is very high with 91 countries, there is a tendency that the majority of lead authors are from the Global North, and less than a third of the articles are led by authors located in the Global South. This depicts an overall determined imbalance of publication origins as shown by Blicharska et al. (2017), Collyer (2018), Jeffery (2014), Karlsson et al. (2007) and Rokaya et al. (2017). Previous accounts found a domination of SDG-related publications from European regions (Sweileh 2020). Within our analysis, all of the countries from which most lead authors come are listed OECD countries and can thus be described as belonging widely to the Global North (Blicharska et al. 2017), underlining the data gap between the Global North and the Global South (Karlsson et al. 2007). A comparable imbalance was found regarding the countries most affected by climate change which are equally underrepresented in environmental science (Blicharska et al. 2017). This is even more pronounced since researchers from the Global North tend to hold higher posts within research teams, compared to those from the Global South (Jeffery 2014). Such power imbalances can, however, be tackled by a higher contextual transparency in the research conduct (Maina-Okori et al. 2018), and other SDG-aimed research reviews show a similar bias toward the European regions (Sweileh 2020), while for instance SDG 5 was least researched in the Western Pacific regions. Deeper contextual information is often omitted in research papers due to the demand in brevity; there are counterexamples that incorporate the author's background into the research context (Maina-Okori et al. 2018).

The proportion of papers that utilizes gender as a research focus was less than 10% and thus relatively low. Based on the word-driven analysis, we identify clear groups differentiated based on the topical focus, methodological approaches and theoretical foundation. The literature ranges from rather qualitative and discourse-oriented approaches to more survey and interview-driven literature. A second gradient in the literature ranges across different systems, for instance from agricultural systems to different organizations and their development.

(ii) Concerning our second research interest, we identify a lack in coherent framing of relevant terms. Often no definition of sustainability is given, and only the sustainability goals (SDGs or MDGs) are used as a framework to refer to sustainability. With other diverse sources such as the Brundtland report and the WCED 1987 as well as the Agenda 21 and the Rio Conference 1992 being cited to define the sustainability understanding of the respective paper, it is clear that a coherent and uniting framing of sustainability science is still lacking in this specific scientific literature. After all, these sources are quite old, and much has been published since (e.g., Clark 2007, etc.). One article we want to highlight that situates itself both within sustainability science and includes a gendered perspective is by Ong et al. (2020). They classified their research on queer identities within tourism and leisure research as social sustainability, arguing that social sustainability advocates equal opportunities and human rights for both individual and social well-being (Ong et al. 2020). Another paper which we want to mention is that by Maina-Okori et al. (2018) because it argues from a perspective that was taken up very little by the analyzed articles. They call for the inclusion of Black feminist thought and Indigenous knowledge in sustainability science research as well as the reflection on colonial history, which is not given enough attention in research on climate protection, education for sustainable development or land use rights. Concerning the knowledge types of sustainability (systemic, normative and transformative), our expectation that system knowledge widely dominates the literature was confirmed, with a combination of systemic and normative as well as systemic and transformative knowledge being also abundantly published. We cautiously interpret this as a reflection of the research we investigated on partial knowledge, while an overarching integration of knowledge types is needed for many of the sustainability challenges we face, including the ones associated with gender. While a problem orientation dominates much of the discourse, only few papers focus on normative or transformative knowledge. In their paper on environmental justice in urban mobility decision-making, for instance, Chavez-Rodriguez et al. (2020) combined all three knowledge types. First, they dismantled how discourses and narratives on urban mobility are often socially exclusionary and reproduce patterns of marginalization (systemic knowledge). They then argued that environmental justice as an intersectional system must include mobility justice (normative knowledge). In the end, they proposed a framework definition of ‘queering the city’ which shall help to create a more emancipatory narrative on urban mobility (transformative knowledge) (Chavez-Rodriguez et al. 2020). However, the small proportion of papers doing this indicates a lack of an overarching perspective when it comes to the diverse knowledge types, which can be considered relevant to overcome the problems we face globally.

(iii) Concerning the third research interest, the investigated literature mainly contributed to few SDGs, with SDG 5 ‘Gender Equality’, SDG 8 ‘Decent Work and Economic Growth’, SDG 3 ‘Good Health and Well-being’ and SDG 4 ‘Quality Education’ being in the main focus. All other SDGs were mentioned by less than 10% of the papers. This underlines that most scientific papers are rather focused than holistic when viewed through an SDG perspective. While no research can meaningfully engage with all SDGs, we would propose that a wider coverage of other SDGs to be engaging more in gender research would be beneficial.

Furthermore, SDGs are often mentioned as a boundary framework while missing the chance to deeply engage with the conceptual foundation or purpose of the SDG framework. Within the vast majority of papers, the SDGs are referred to as a means to the end of positioning the research within a current discourse. In other words, many papers do not work with the SDGs to contribute toward its strategies and solutions, but instead to simply be affiliated to the broad movement of sustainable development. This reference often takes place in the introduction or conclusion of the paper and is of no importance in the actual research. This gives the impression that the popularity of the SDGs, which goes beyond the discourse of sustainability science, is used to categorize or identify one's own research within the light of sustainability.

However, there are many constructive contributions toward a critical perspective on the integration of the Sustainable Development Goals. Ong et al. (2020) highlight that queer identities are not included within the SDGs, yet they relate their research to several SDGs such as SDG 5, 10, 11 and 16. They argued that “these goals demonstrate the centrality of inclusivity to the development of sustainable communities'' (Ong et al. 2020, p. 1477). Poku et al. (2017) went one step further and postulated the need to queer the SDGs by linking opportunities for addressing social exclusion for LGBTI in Africa to the SDGs.

(iv) Based on the set of the literature we analyzed, all in all, gender and sustainability research utilize a broad range of methods that allow for different forms of knowledge (Spangenberg 2011). However, we find strong links between specific methods and certain areas of sustainability within the emerging groups within the identified literature. For example, nearly all research in cluster seven, which focuses on corporations and economy, uses a quantitative statistical approach, while other clusters are defined by qualitative methods and lack quantitative ones. This methodological homogeneity within certain research clusters highlights already established preferences for certain methods in specific fields of research, disciplines and focal topics where some methods are more adequate than others. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of gender and sustainability, however, we critically regard these links as they often emerge from previously existing research traditions and thus lack methodological plurality.

(v) Within the examined literature, the two investigated understandings of gender, namely non-binarity and intersectionality, are differently acknowledged and incorporated in the reviewed literature. Very few authors challenge the gender binary approaches within the considered scientific articles, where less than a fifth of the papers considered gender to be socially constructed (14%) or non-binary (5%). While the vast majority of papers do not explicitly state that they build on a binary understanding of gender, they nevertheless replicate or suggest a binarity in their focus and/or empirical categorization that clearly indicates a binary division. Moreover, some papers put forward ethical or moral differences in men and women when it comes to sustainability. For example, some researchers are led by gender assumptions which often originate from the field of eco-feminism such as women being more caring of the environment, since they have a natural disposition to care and to being a mother (Brough et al. 2016; Lau et al. 2021). When such proposals do not pay attention to gender norms and power imbalances, they run the risk of further naturalizing the gender binarity as ‘immutable biological differences’ (Lau et al. 2021). Lastly, we find that gender differences are nearly always illustrated on behalf of women. While an explicit focus on women’s lives in research can be useful and necessary, it should not be limited to it. A narrow focus on women excludes many other genders from research and can furthermore evoke the assumption that gender equality and sustainability are ‘women’s issues’ (Lau et al. 2021).

No pattern regarding the temporal increase or decrease of non-binary or socially constructed gender understanding can be found in the body of literature examined by us, in absolute numbers or in proportions.

In summary, theories and findings from gender studies like the constructivist turn and queer theory as well as intersectionality are yet to permeate the field of sustainability research.

Within the examined research, there is clearly a limited acknowledgment of intersectionality, with less than a third of all articles using other social categories apart from gender in their analysis or applying even an intersectional approach. Intersectionality was thus applied in diverse research cluster groups underlining the importance for a diverse methodological approach to investigate intersectionality (Rice et al 2019). Intersectionality is most frequently addressed in the research cluster focusing on gender and institutions, meaning that this literature named and utilized the concept. We refrained from making a deeper analysis of whether more than one social category was analyzed, which would demand a deeper text analysis. We refrained from such interpretation, because due to the short form of peer-reviewed papers such information is often omitted or not coherently reported. However, intersectionality often is hardly mentioned in the analyzed papers, neither as a word nor as a concept. Instead, different identity categories than gender are merely used to further characterize the research subject(s). For instance, Theobald et al. (2017) referred to intersectionality in their research regarding gender mainstreaming within health and neglected tropical diseases, highlighting the impact of gender on health issues while acknowledging the intersection of gender with other axes of inequality. They illustrated how dimensions of gender interact with poverty, (dis)ability, occupation, power, geography and other individual positionalities in shaping impacts on health and care programs (Theobald et al. 2017).

The concept of intersectionality is applied on a diversity of topics. As Rice et al. (2019) point out, there is also “no single method for undertaking intersectional research. It can be used with many methods and approaches, quantitative and qualitative” (Rice et al. 2019, p. 418). In addition to previously mentioned example papers from our analysis focusing on tourism as well as sustainability education, there are suggestions to match the SDGs with an intersectional conceptualization (Stephens et al. 2018; Zamora et al. 2018). Similarly, attempts to integrate intersectionality to other long standing policy communities such as global health exist (Theobald et al. 2017). Hardy et al. (2020) integrate the concept into research on indigenous youth. Such papers showcase the strong connectivity of the concept to many different branches of research. By integrating diverse voices, showcasing how injustices are intertwined and that different reasons for injustices amplify each other, intersectionality can serve as a strong foundational concept within sustainability science (Maina-Okori et al. 2018). Our review showcases that the majority of papers focusing on gender do not utilize the concept. Within the analyzed literature, overall citation rates are comparably low and the most highly cited papers do not utilize the concept. In summary, intersectionality has not fully reached the sustainability science community as of yet.

Before we come to our final conclusions, we would like to again reflect upon our positionality as scholars researching this topic. We recognize that we as scholars have a highly privileged position in academia as well as the world, both regarding resources and the institutions at which we are working in that make our voices heard. We would like to use this position to address the existing power dynamics within sustainability science to other equally privileged scholars. We hope to reflect upon and challenge the deeply embedded power structures within Western academic knowledge production as well as considering the role gender inclusive and intersectional approaches can play in addressing sustainability problems. This paper is a mere attempt to grasp the research that has so far been conducted upon gender in sustainability science, and from our end a definitive work in progress. Yet, this is then also the ultimate goal in writing this paper, to progress, even if it is only one step at a time.

Finally, we would like to give an outlook on what findings have been published in the period following our research period. For this purpose, we again entered our search string in the Scopus database and searched for articles on gender in sustainability science for the period January 2021 to October 2022. This search yielded a further 2.304 articles after applying our exclusion criteria. To narrow the analysis, we sorted these results by citation and looked at the articles with the highest citations. This cursory scan reveals that many papers consider gender only as an empirical category of analysis, and that these are thematically related to the field of economics and health, for example, with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic. Only a few focus on gender as a central research interest. These results also largely coincide with the results of this review. As a perspective, we would like to highlight the COVID-19 pandemic once again, because the analyses and studies that have been conducted in connection with gender can shed new light on the role of gender during global crises and are therefore an important contribution to sustainability science.

Conclusion

We have systematically examined the development and state of research focusing on gender in sustainability science by means of a quantitative analysis of 1054 peer-reviewed papers published between 1991 and 2021. Our analysis clearly illustrates that while a diverse body of literature on gender exists within sustainability science, several research clusters with different focal points are emerging. As all these branches of the literature utilize diverse methodological approaches and different conceptual foundations; there is a lack of a more holistic integration of the topic within the broader literature. While the word “holistic” is a clearly big claim, we can underline based on our review that conceptual foundations, definitions and agreement on the most simple terms and procedures are lacking to this day, while at the same time the problems of gender issues are mounting.

It is highly likely that the recent surge in literature will increase. Thus, we put forward five tangible suggestions on how the research community could further evolve below.

-

(1)

Although a research focus on gender will not solve the prevalent problem of postcolonial research structures, an increasing diversity of voices with different backgrounds would bring forth new and diverse knowledge. At this point, we would like to draw particular attention to the theories and bodies of knowledge of Black feminists, as well as Indigenous knowledge and decolonial approaches.

-

(2)

We advise the research community to build on distinct definitions of sustainability as well as to put a strong focus on the contribution toward solutions for sustainability challenges. The creation of descriptive-analytical system knowledge which outlines the current status quo of gender equality with regards to sustainability and points out many current problems is a necessary and helpful first step. Yet, knowing the mechanics and causes of a problem does not translate into knowing how to approach and move toward a state of more equality. We therefore urge scholars to also apply a solution-oriented perspective in their research regarding gender in sustainability science.

-

(3)

Moreover, although there is seemingly much research that discusses gender issues, only a low proportion of those papers actively engage with gender on an empirical level. To achieve the goal of a world with less inequalities, more research should enable deep normative understandings of diverse and inclusive recognitions of gender identities and associated social, economic and cultural consequences as well as investigate pathways of transformation and sustainable change. While such normative claims may facilitate ethical evaluations, more work is needed to enable an inclusive understanding of the context of such evaluations.

-

(4)

All in all, the emerging research clusters showcase that there are engaged researchers that focus on gender within sustainability science. However, there are gaps between the clusters where for example a recognition of intersectionality would hold benefits for more researchers, and a higher methodological plurality may benefit knowledge production, to name two examples. What is clear is that within sustainability science, gender issues are widely ignored to this day, and based on the systematic review we conducted, we can encourage more research on gender issues and diversity.

-

(5)

When gender is integrated as an analytical foundation or a concept associated with gender is being utilized within sustainability science, the critical perspective that the academic field of gender studies has developed over the past decades is seldom integrated, e.g., theories on the social construction of gender, queer theory and Black feminist theory. The concept of intersectionality should especially be further acknowledged, as it may shed a stronger light on perceived and endured injustices and give hope for a greater involvement of researchers not only to investigate these issues, but also to help to overcome them.

While our review only focuses on peer-reviewed literature and thus can only offer a specific perspective, we hope yet to offer a contribution to the bigger picture, thereby creating a link between gender and sustainability.

References

Abasahl F, Kelarestaghi KB, Ermagun A (2018) Gender gap generators for bicycle mode choice in Baltimore college campuses. Travel Behav Soc 11:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.01.002

Abdelali-Martini M, Amri A, Ajlouni M, Assi R, Sbieh Y, Khnifes A (2008) Gender dimension in the conservation and sustainable use of agro-biodiversity in West Asia. J Socio-Econ 37(1):365–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2007.06.007

Abson DJ, von Wehrden H, Baumgärtner S, Fischer J, Hanspach J, Härdtle W, Heinrichs H, Klein AM, Lang DJ, Martens P, Walmsley D (2014) Ecosystem services as a boundary object for sustainability. Ecol Econ 103:29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.01

Adjei M (2019) Women’s participation in peace processes: a review of literature. J Peace Educ 16(2):133–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2019.1576515

Agarwal B (1992) The gender and environment debate: lessons from India. Fem Stud 18(1):119–158. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178217

Agarwal B (1998) The gender and environment debate. In: Roger K, Bell D, Penz P, Leeson F (eds) Political ecology. Global and local. London/New York, pp 193–219

Agius C, Mundkur A (2020) The Australian Foreign Policy White Paper, gender and conflict prevention: ties that don’t bind. Aust J Int Aff 74(3):282–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2020.1744518

Allen E, Lyons H, Stephens JC (2019) Women’s leadership in renewable transformation, energy justice and energy democracy: redistributing power. Energy Res Soc Sci 57:101233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101233

Al-Rashid MA, Nahiduzzaman KM, Ahmed S, Campisi T, Akgün N (2020) Gender-responsive public transportation in the Dammam metropolitan region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 12(21):9068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219068

Alston M, Whittenbury K (eds) (2013) Research, action and policy. In: Addressing the gendered impacts of climate change. Springer, Dordrecht, New York

Andajani S, Chirawatkul S, Saito E (2015) Gender and water in Northeast Thailand: inequalities and women’s realities. J Int Women’s Stud 16(2):200–212

Ansong D, Renwick CB, Okumu M, Ansong E, Wabwire CJ (2018) Gendered geographical inequalities in junior high school enrollment: do infrastructure, human, and financial resources matter? J Eco Stud 45(2):411–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-10-2016-0211

Appiah EM (2015) Affirmative action, gender equality, and increased participation for women, which way for Ghana? Statut Law Rev 36(3):270–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/slr/hmv016

Arevalo JA (2020) Gendering sustainability in management education: research and pedagogy as space for critical engagement. J Manag Educ 44(6):852–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562920946796

Assoumou-Ella G (2019) Gender inequality in education and per capita GDP: the case of CEMAC countries. Econ Bull. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3391773

Azanaw A, Tassew A (2017) Gender equality in rural development and agricultural extension in Fogera District, Ethiopia: implementation, access to and control over resources. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev 17(4):12509–12533. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.80.16665

Azmi Z (2020) Discoursing women’s political participation towards achieving sustainable development: the case of women in Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS). Kajian Malaysia 38(1):67–88. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2020.38.s1.5

Badstue L, Petesch P, Farnworth CR, Roeven L, Hailemariam M (2020) Women farmers and agricultural innovation: marital status and normative expectations in rural Ethiopia. Sustainability 12(23):9847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239847

Bauhardt C (2022) Queer ecologies. In: Gottschlich D, Hackfort S, Schmitt T, von Winterfeld U (eds) Handbuch Politische Ökologie: Theorien, Begriffe, Konflikte, Methoden. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, pp 427–432

Belahsen R, Naciri K, El Ibrahimi A (2017) Food security and women’s roles in Moroccan Berber (Amazigh) society today. Matern Child Nutr 13:e12562. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12562

Benítez B, Nelson E, Romero Sarduy MI, Ortiz Perez R, Crespo Morales A, Casanova Rodriguez C et al (2020) Empowering women and building sustainable food systems: a case study of cuba’s local agricultural Innovation Project. Front Sustain Food Syst 4:554414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.554414

Benjamin EO, Ola O, Buchenrieder G (2018) Does an agroforestry scheme with payment for ecosystem services (PES) economically empower women in sub-Saharan Africa? Ecosyst Serv 31:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.03.004

Betron M, Thapa A, Amatya R, Thapa K, Arlotti-Parish E, Schuster A et al (2020) Should female community health volunteers (FCHVs) facilitate a response to gender-based violence (GBV)? A mixed methods exploratory study in Mangalsen, Nepal. Glob Public Health 16(10):1604–1617. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1839929

Birindelli G, Iannuzzi AP, Savioli M (2019) The impact of women leaders on environmental performance: evidence on gender diversity in banks. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(6):1485–1499. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1762

Blicharska M, Smithers RJ, Kuchler M, Agrawal GK, Gutiérrez JM, Hassanali A, Huq S, Koller SH, Marjit S, Mshinda HM, Masjuki HH, Solomons NW, van Staden J, Mikusiński G (2017) Steps to overcome the North-South divide in research relevant to climate change policy and practice. Nat Clim Change 7(1):21–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3163

Bosmans M, Nasser D, Khammash U, Claeys P, Temmerman M (2008) Palestinian women’s sexual and reproductive health rights in a longstanding humanitarian crisis. Reprod Health Matters 16(31):103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31343-3

Brandt P, Ernst A, Gralla F, Luederitz C, Lang DJ, Newig J, Reinert F, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H (2013) A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol Econ 92:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.008

Brough AR, Wilkie JEB, Ma J, Isaac MS, Gal D (2016) Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J Consum Res 43(4):567–582. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw044

Brundtland GH (1987) Our common future: report of the World Commission on environment and development

Buechler S, Vázquez-García V, Martínez-Molina KG, Sosa-Capistrán DM (2020) Patriarchy and (electric) power? A feminist political ecology of solar energy use in Mexico and the United States. Energy Res Soc Sci 70:101743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101743

Bührmann AD (2009) Intersectionality—ein Forschungsfeld auf dem Weg zum Paradigma? Tendenzen, Herausforderungen und Perspektiven der Forschung über Intersektionalität. GENDER Zeitschrift Für Geschlecht, Kultur Und Gesellschaft (2):28–44

Burkhardt K, Nguyen P, Poincelot E (2020) Agents of change: women in top management and corporate environmental performance. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(4):1591–1604. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1907

Bürkner H-J (2012) Intersectionality: how gender studies might inspire the analysis of social inequality among migrants. Popul Space Place 18(2):181–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.664

Burney J, Alaofè H, Naylor R, Taren D (2017) Impact of a rural solar electrification project on the level and structure of women’s empowerment. Environ Res Lett 12(9):095007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7f38

Burridge N, Maree Payne A, Rahmani N (2016) ‘Education is as important for me as water is to sustaining life’: perspectives on the higher education of women in Afghanistan. Gend Educ 28(1):128–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1096922

Butler J (1990) Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge, London

Chavez-Rodriguez L, Lomas RT, Curry L (2020) Environmental justice at the intersection: Exclusion patterns in urban mobility narratives and decision making in Monterrey, Mexico. DIE ERDE J Geogr Soc Berlin 151(2–3):116–128. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-2020-479

Cheng KKY, Ghajarieh ABB (2011) Rethinking the concept of masculinity and femininity: focusing on Iran’s female students. Asian J Soc Sci 39(3):365–371. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853111X577613

Chindarkar N (2012) Gender and climate change-induced migration: proposing a framework for analysis. Environ Res Lett 7(2):025601. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/2/025601

Clark WC (ed) (2007) Sustainability science: a room of its own. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104(6):1737–1738

Clark W, Harley A (2019) Sustainability science: towards a synthesis. Sustainability Science Program Working Papers. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42574531.

Cohn C, Duncanson C (2020) Women, Peace and security in a changing climate. Int Fem J Polit 22(5):742–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2020.1843364

Collyer FM (2018) Global patterns in the publishing of academic knowledge: global North, global South. Curr Sociol 66(1):56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116680020

Combahee River Collective (2018) A black feminist statement. In: Feminist Manifestos. NYU Press, pp 269–277. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvf3w44b.63 (Original work published 1977)

Conference of the Swiss Scientific Academies, Forum for Climate and Global Change, & Swiss Academy of Science (1997) Research on sustainability and global change—visions in science policy by Swiss researchers. http://www.proclim.unibe.ch/visions.html

Cortina R (2010) Gender equality in education: GTZ and indigenous communities in Peru. Development 53(4):529–534. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2010.71

Crenshaw KW (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. In: University of Chicago legal forum, vol 1, no 8. pp 138–167

Crockett C, Cooper B (2016) Gender norms as health harms: reclaiming a life course perspective on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Reprod Health Matters 24(48):6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2016.11.003

Curth J, Evans S (2011) Monitoring and evaluation in police capacity building operations: ‘women as uniform?’ Police Pract Res 12(6):492–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2011.581440

Dankelman I (ed) (2010) Gender and climate change: an introduction. Earthscan, London

Denton F (2002) Climate change vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation: why does gender matter? Gend Dev 10(2):10–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070215903

Drafor I, Kunze D, Al Hassan R (2005) Gender roles in farming systems: an overview using cases from Ghana. Ann Arid Zone 44(3&4):421–439

Dyer M (2018) Transforming communicative spaces: the rhythm of gender in meetings in rural Solomon Islands. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09866-230117

Eger C, Munar AM, Hsu C (2022) Gender and tourism sustainability. J Sustain Tour 30(7):1459–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1963975

Elmagrhi MH, Ntim CG, Elamer AA, Zhang Q (2018) A study of environmental policies and regulations, governance structures, and environmental performance: the role of female directors. Bus Strateg Environ 28(1):206–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2250

Elsevier B.V. (2020) Scopus. https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic#basic

Enarson EP, Chakrabarti PG (eds) (2009) Women, gender and disaster: global issues and initiatives. ebrary, Inc. SAGE, Los Angeles