Abstract

Ecosystem-based management and marine spatial planning (MSP) represent novel approaches intended to transform marine governance and improve ecosystems. The transformation can be supported by sustainability initiatives such as decision-support tools, which inform changes in management strategies and practices. This study illustrates the potential and challenges of such sustainability initiatives to promote deliberative transformative change in marine governance systems. Specifically, it focuses on the amplification processes of the Symphony tool for ecosystem-based MSP in Sweden. Our findings suggest that the amplification of sustainability initiatives is driven by informal networks, coalition forming, resource mobilization skills, a shared vision, trust, experimentation, and social learning. Our results also highlight that in the face of institutional challenges such as sparse financial resources, uncertain institutional support, and divided ownership, a strategic way forward is to simultaneously work on parallel amplification processes, as they may enable each other. Further, we find that a key challenge in amplification across governance scales is the need for significant adjustments of the original innovation, to meet differing needs and competences. This highlights the broader challenge of achieving transformative change across scales in heterogenous and fragmented multilevel governance systems. Co-production of knowledge and early stakeholder interaction to ensure accessibility and availability can improve the chances of successful amplification. To move beyond a mechanistic understanding of steps and processes, future research on sustainability initiatives should consider the interplay between strategic agency, social learning, and institutional context in driving amplification processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Marine ecosystems are under increasing pressure from human activities including coastal industries, fishery, shipping, and climate change (Halpern et al. 2019). Effective policies and management actions are needed across different levels of marine governance systems to reduce anthropogenic pressures on the marine environment and to enable the sustainable use of marine resources (Duarte et al. 2020). Coastal states are increasingly urged to transform their sectoral and fragmented marine governance regimes and to implement integrated and holistic management approaches, such as ecosystem-based management and marine spatial planning (MSP) (Kelly et al. 2018). EU directives concerning marine waters such as the Marine Spatial Planning Directive, the Water Framework Directive, and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive all require the application or supposedly comply with ecosystem-based management (Westholm 2018). Importantly, holistic marine management requires a sophisticated understanding of the compounding impacts of anthropogenic pressures, including climate change, on interconnected ecosystem components (Foley et al. 2010; Halpern et al. 2008).

Cumulative impact assessment has been presented as an approach to guide integrated marine management (Halpern et al. 2008). Cumulative impact is calculated as a relative index based on spatially explicit information about anthropogenic pressures, the distribution of ecosystem components and the approximate sensitivity of each ecosystem component to each human pressure (Halpern et al. 2008). Cumulative impact assessment has proven effective in supporting planners in understanding where management actions are effective or inadequate (Halpern et al. 2019) and in the development of ecosystem-based marine planning (Fernandes et al. 2017).

Scholars studying transformation processes in marine governance and beyond have noted that transformations often start out as small-scale sustainability initiatives (Bennett et al. 2016; Moore et al. 2015). Understanding how sustainability initiatives can amplify their impact beyond the original realm is key to enable sustainability transformations (Lam et al. 2020). Recent research on transformations towards more sustainable marine ecosystems emphasizes the need to study the adoption of new management practices in the context of institutional dynamics and barriers (Kelly et al. 2018). Meanwhile, literature on strategic agency argues that the purposeful use of resources, skills and strategies by individuals and collectives is pivotal in moving a process of transformation forward (Westley 2002).

Drawing on the case of Symphony, a tool for ecosystem-based MSP in Sweden (HaV 2018; Hammar et al. 2020; Jonsson et al. 2021), this paper analyses how a sustainability initiative amplifies its impact. To do so, the study applies a typology of amplification processes of sustainability initiatives, developed by Lam and colleagues (2020). Moving beyond a mechanistic analysis of steps and processes, we seek to add nuance to the analysis of amplification processes by considering the change agents driving these processes, and the skills and strategies they employ, as well as the institutional context in which they operate.

Thus, the aim of this paper is to better understand the role of strategic agency, social learning and institutional context in driving the amplification of a sustainability initiative towards broader transformative change in marine governance.

In the following sections, we briefly describe sustainability initiatives in the context of marine governance and link Lam et al.’s (2020) typology to research on strategic agency (Westley et al. 2013), social learning (Reed et al. 2010; Suškevičs et al. 2018), and institutional context (Westley et al. 2013; Kelly et al. 2018). We then outline the case study and method used for this paper and present results from our analysis of the development and amplification process of the Symphony tool. The final sections discuss our findings and draw conclusions for future research.

Linking strategic agency, learning, and institutional context to understand the amplification of sustainability initiatives

Amplification of sustainability initiatives and transformational change

Sustainability initiatives are broadly defined as potential solutions to sustainability problems that may over time coalesce to shift dominant ways of thinking, doing, and governing, thereby driving sustainability transformations (Lam et al. 2020; Pereira et al. 2020). They typically start out as bottom-up, small-scale initiatives that have the potential to change established governance regimes (Kelly et al. 2018). In the context of marine governance, research on community-led initiatives in Indonesia (Glaser et al. 2010) and the implementation of ecosystem-based management in the Baltic Sea (Österblom et al. 2010) has shown that sustainability initiatives can provide important stimuli to alter existing regimes and prompt broader institutional change.

For sustainability initiatives to be successful in transforming existing governance regimes and reach a systemic impact, they need to be amplified across multiple governance levels, decision-making phases, and geographical scales (Olsson et al. 2014). Lam et al. (2020) propose a typology of eight amplification processes that describe the diverse actions deployed by sustainability initiatives together with other actors to purposively increase their transformative impact. These eight amplification processes can be summarized in three main categories (see Table 1).

First, amplifying within an initiative takes place by either stabilizing or speeding up its impact. Stabilizing refers to strengthening, and more deeply embedding an initiative in its context to make it more resilient to challenges, improve its impact, and ensure that it lasts longer (Bennett et al. 2016; Valkering et al. 2017; Gorissen et al. 2018). Speeding up refers to increasing the pace by which an initiative creates impact to adequately address sustainability challenges (Ehnert et al. 2018).

Second, amplifying out consists of either growing, replicating, transferring, or spreading. Growing entails doing the same initiative in a similar context (Bennett et al. 2016; Naber et al. 2017), replicating refers to doing the same initiative in a dissimilar context (Moore et al. 2015; Hermans et al. 2016; Bennett et al. 2016; Naber et al. 2017), and transferring means taking an initiative and implementing a similar but independent one in a different place, adapted to the new but similar local context (Withycombe et al. 2016). Spreading refers to disseminating core principles and approaches to other independent initiatives in dissimilar contexts (Moore et al. 2015).

Third, amplifying beyond an initiative takes place through either scaling up or scaling deep. Scaling up refers to institutionalizing the impact of the initiative by changing the rules or logics of incumbent regimes (Hermans et al. 2016), and scaling deep entails changing the underlying norms, values, and beliefs that determine individual and collection perception and action (Rotmans and Loorbach 2008).

Strategic agency, social learning, and institutional context

While the typology presented by Lam et al. (2020) offers a way of tracking how sustainable initiatives can lead to transformations, it provides limited insights into the dynamics of transformative change in terms of the change agents involved, the strategies and skills they employ, and the hindering or enabling institutional context they face in moving from niche idea to wider systemic impact.

Pelling and colleagues (2008) have highlighted the importance of what they call “shadow spaces”—spaces within and between organizations that allow individuals to experiment with new knowledge and develop new practices and strategies. Gunderson (1999) finds that because the members of such networks are under less scrutiny, they have greater flexibility to develop alternative policies, dare to learn from each other, and think creatively about how to solve emerging problems.

Findings about sustainability initiatives highlight that transformative change in environmental governance regimes critically depends on strategic agency (Westley et al. 2013) and social learning (Pahl-Wostl 2009).

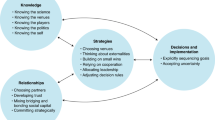

Westley and colleagues (2013) find that change agents deploy various skills and strategies to effect transformative change including developing and sharing knowledge and innovation, building a common vision, mobilizing resources, and building social networks, trust, and legitimacy.

Social learning occurs through social interactions and processes between actors within a social network and manifests in outcomes that become situated within wider social units or communities of practice (Reed et al. 2010). Through social learning, individuals can build networks, align their actions, and build strategic agency for transformative change (Ducrot 2009; Pahl-Wostl 2002; Lebel et al. 2010).

Crucially, the extent to which sustainability initiatives driven by learning and strategic agency can transform governance regimes and systems depends on their ability to overcome institutional barriers (Westley et al. 2013; Järnberg et al. 2018). Typically, institutions are resistant to change due to path dependency, incumbent actors, and vested interests (Kelly et al. 2018). However, as Dorado (2005) explains, at different points in time, institutional contexts can open up for change and innovation. To be successful, change agents can adapt their strategies to take advantage of emerging opportunities and seize “windows of opportunity” (Kingdon 1995; Olsson et al. 2004).

Materials and methods

Case study

This study explores the development and amplification of the Symphony tool, which was developed to support ecosystem-based MSP in Sweden (Hammar et al. 2020). Following the EU Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (EC 2014), Sweden adopted its first national marine spatial plans in 2022 after 8 years of formal preparation and stakeholder dialogue (HaV 2022). The Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM) is responsible for implementing the EU Maritime Spatial Planning Directive in Sweden and developing national marine spatial plans. While Swedish marine spatial plans are not legally binding, they are guiding for decisions on marine policy, consenting procedures, and local development plans (Hammar et al. 2020).

The Symphony tool is based on a cumulative impact assessment methodology developed by Halpern et al. (2008). The tool consists of four elements: ecosystem components, human pressures, a sensitivity matrix, and a GIS-based front-end platform for analysis. It includes information and maps about 41 pressures from human activities (e.g. eutrophication, fisheries, and offshore energy) and 32 ecosystem components (e.g. fishes, habitats, and ecological functions) representing the marine environment in the Swedish area of the Kattegat–Skagerrak, the Baltic Proper, and the Gulf of Bothnia. The calculation of the impact of human pressures on ecological components draws on a sensitivity matrix representing how sensitive each ecosystem component is to each human pressure. Symphony is an extension of the cumulative impact assessment methodology developed by Halpern et al. (2008), as it includes scenario analysis which allows users to assess the impact of different marine management plans (Hammar et al. 2020). In addition, the future climate change effect of temperature, salinity, and ice cover have been implemented as human pressure layers, although this was done after the national marine spatial plans were developed (Wåhlström et al. 2022).

Method

To explore the amplification process of the Symphony tool and the role of strategic agency, learning, and institutional context, we conducted semi-structured interviews with key informants involved in the development of the tool. Informants were selected based on how central they were in the development of Symphony, to understand the amplification strategies they employed, and the role of agency, learning, and institutional context. In total, we conducted interviews with nine informants in 2019 and 2020 (see Appendix 1 for supplementary information on methodology). Interviews were transcribed and analysed using qualitative data analysis software and deductive coding based on the theoretical approaches to amplification, strategic agency, social learning, and institutional context that are presented in Tables 1 and 2. In addition, we analysed grey and academic literature on the Symphony tool and the development of MSP in Sweden. We also participated in and assessed notes of meetings with stakeholders of the Formas-funded ClimeMarine project, which contributed to the development of Symphony.

Results

Figure 1 shows how the Symphony tool was developed and amplified in the context of Sweden’s MSP process. Based on Lam et al.’s (2020) typology, we identify four development and amplification phases of the Symphony tool, described below. The phases contain elements of three amplification processes: stabilizing (amplifying within the initiative), replication (amplifying out of the initiative), and transfer (amplifying out of the initiative). As for the other amplification processes described by Lam et al. (2020), we did not find evidence of speeding up, growing, or spreading the initiative. The amplification processes of scaling up and scaling deep were outside the scope of this study.

After laying out the development and amplification phases, we analyse the role of strategic agency, learning, and institutional context in amplifying Symphony’s impact.

Inception phase

The inception phase started in 2009 when the Swedish government convened the Commission on Marine Spatial Planning to develop a new system for national planning of the sea ①. The Commission proposed a national marine spatial planning act that follows the ecosystem-based management approach and involves stakeholders in an iterative planning process (Havsplaneringsutredning 2010). The Commission’s report was followed by two reports by SwAM on the application of the ecosystem approach to MSP (HaV 2012) and an analysis of current marine management practices in Sweden (HaV 2015). Both reports mention cumulative impacts of human pressures, but without making any specific recommendation on how they should be addressed in MSP. The EU Maritime Spatial Planning directive was adopted in July 2014 (EC 2014) and was subsequently transposed into Swedish law in 2015 ②. With MSP being a new management phenomenon in Sweden, the institutional context was favourable for introducing novel ideas and innovations—the MSP process constituted what can be referred to as a window of opportunity (Olsson et al. 2004). At this point in time, key individuals at SwAM proposed a new cumulative impact assessment approach for more ecosystem-based marine management, and it was accepted to be tested as part of the national MSP process, with resources available to start development.

Stabilizing phase

The stabilizing phase, where Symphony was developed and institutionalized, started with data scoping, collection, and analysis for the back-end development of the tool led by SwAM ③. Following procurements, national and international expertise was contracted for scientific counselling. Simultaneously, SwAM had started working on a roadmap for MSP which was published in September 2016 ④. Subsequently, SwAM held a stakeholder dialogue about the first draft of the marine spatial plans between December 2016 and April 2017. The Symphony tool is mentioned in the roadmap for the first time and described as a tool to assess the cumulative environmental impact of marine spatial plans (HaV 2016). To develop the front end of the Symphony tool, SwAM staff initiated a procurement for a test version. The University of California Santa Barbara’s SeaSketch cumulative impact assessment tool was selected for this trial ⑤. However, the development of a Swedish version of SeaSketch had to be terminated in 2017 due to legal concerns related to storage of personal data and jurisdictions. This coincided with when Symphony would have started to be used in the MSP process, as SwAM started the development of the second draft of marine spatial plans in the final quarter of 2017 ⑥. To address the lack of a fully functioning cumulative impact assessment tool, SwAM decided to procure consultants to develop a proprietary version of the Symphony tool in late 2017 ⑦. Work on a first, fully integrated version of the Symphony tool was concluded in 2018 by the consultants. This version was, however, not available as an interactive tool that marine spatial planners could use themselves, and any simulations had to go through the consultants. While the consultants worked fast, there were still lag times between planners’ requests and delivered analyses. While Symphony could be used by the planners, it was hence not as seamlessly integrated into the planning process as intended.

The second draft of the marine spatial plans was published for public consultation between February and August 2018 ⑧. A third draft of the marine spatial plans was developed by SwAM until March 2019 ⑨ and open to the public for official review until June 2019 ⑩. During this period, Symphony was used intensively for analyses underpinning the strategic environmental assessments related to the plans. In December 2019, SwAM submitted a proposal for marine spatial plans to the Swedish government ⑪, which was adopted by the Swedish government in February 2022.

Replication and further stabilization phase

In parallel, in what we refer to as the replication and further stabilization phase, the Symphony tool was significantly refined (stabilization), and processes were started to spread its use to Swedish municipalities and county administrative boards (replication). This phase commenced with the start of the ClimeMarine project in December 2017 ⑫. The main objective of the ClimeMarine project was to climate-proof ecosystem-based management and MSP of Swedish marine resources. To that end, the project facilitated the inclusion of future climate change data and knowledge into the Symphony tool (Wåhlström et al. 2022). Specifically, the project developed showcases of Symphony outputs such as sensitivity matrices and future climate change pressure maps for different climate scenarios.

Moreover, the ClimeMarine project involved Swedish municipalities and county administrative boards in the integration of scientific insights about climate change pressures in the Symphony tool and MSP through a workshop-based learning process. A first workshop was held in 2018 and presented stakeholders with the current version of Symphony and the second draft of the national marine spatial plans. It facilitated a discussion on the inclusion of climate change data, projection uncertainties, and scoring of climate change vulnerabilities. A second workshop was held in 2019, where stakeholders provided feedback on the first results from the development of climate change-related Symphony outputs in terms of their resolution, data visualization, variables, and approach to uncertainty. A third workshop was held in 2020, during which stakeholders had the opportunity to test and give input on a new online beta version of Symphony.

Parallel to the ClimeMarine project, the management of SwAM made the decision in 2017 to develop a second version of the Symphony tool to support national and local work on MSP ⑬. To that effect, the agency’s IT department initiated the development of an in-house version of Symphony. An open-source version of Symphony was launched in 2022, which enables stakeholders such as Swedish municipalities and county administrative boards to access the tool, although based on local copies rather than the in-house tool.

In addition to the workshops involving external stakeholders, the key individuals leading the Symphony development have held various internal capacity-building and information-sharing workshops and presentations at SwAM to build visibility and credibility to stabilize Symphony within the organization.

Transferring phase

During the inception and stabilizing phases, the approach of using cumulative impact assessment in MSP, and Symphony in particular, was noticed among partners in the international community. SwAM initiated collaborations around the tool within its international and bilateral cooperation ⑭. This was later catalysed by internal personnel movements within SwAM, where an employee moved from the MSP unit to the unit for international affairs. In its current transferring phase, the Symphony tool is part of SwAM’s program for international development cooperation, including supporting MSP in countries in the Western Indian Ocean (HaV 2019). Here, the collaboration on a regional Symphony-based cumulative impact assessment tool within the Nairobi Convention has been of particular importance as it engaged government representatives from ten countries. Experience with Symphony has also informed SwAM’s contribution to a range of other projects including the development of the parallel work on the Baltic Sea Impact Index Cumulative Impact Assessment Tool (BSII CAT) of the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission (Helsinki Commission, or HELCOM).

Strategic agency and learning

Results from the interview analysis suggest that there was a small number of key individuals at SwAM who drove the development of Symphony during the inception and amplification stages. In the inception phase, a mid-level manager in charge of MSP at SwAM was searching for more holistic approaches to assess environmental impacts as part of the MSP process, and a second individual, driven by a similar motivation to bring in a holistic perspective in marine environmental management, presented the idea of using cumulative impact assessments for precisely this purpose. The manager instructed the employee, who had some technical expertise on cumulative impact assessments, to lead the development of Symphony, and these two individuals developed the initial concept of the Symphony tool between 2014 and late 2015. A planner at SwAM, with responsibility for strategic environmental assessment of MSP, soon became a strong advocate of applying Symphony in practice and strengthened its usability, thereby playing a key role in stabilizing Symphony as part of the MSP process. The small network at SwAM had support from the wider MSP unit at SwAM and also drew on procured academic expertise and competence at the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that had experience with a similar methodology.

A fourth SwAM staff member joined the network in 2017, and was hired partially to support the development of Symphony and its use in the MSP process. This person saw the potential of Symphony as a practical tool to integrate a more holistic perspective on marine management, and, following an organizational restructuring, took over the project leadership of Symphony during the replication and further stabilization processes. During the organizational restructuring, the originator of the Symphony idea transferred to SwAM’s international unit, where he has been driving processes of transferring Symphony internationally. In this context, Symphony has become a high-profile case for SwAMs international work and is promoted by the highest management level.

Interviews suggest that individual and collective agency and a mutual learning process that engaged all members of the small network were the driving forces behind the initial development phases of the Symphony tool. Specifically, the development processes relied on mutual trust between the different individual network members and their shared motivation and vision that the MSP process was a window of opportunity to introduce a holistic, ecosystem-based, and data-driven element in marine management. Data from the interviews also suggest that the other network members had a high level of confidence in the originator of the Symphony idea, and in his framing of the underlying principles, design, and use case of the Symphony tool. There was also a high level of agreement about the purpose and components of the tool from the beginning of the development process.

The development of the Symphony tool also benefitted from the network members’ ability to mobilize financial and human resources, build partnerships, and take strategic action to ensure that the Symphony tool got developed and implemented. The informal scoping and data collection process that started the stabilization phase was possible because the person in charge of MSP at SwAM leveraged directed MSP-related financial resources to involve consultants, universities, and other government agencies, including Geological Survey of Sweden (SGU), in the development of Symphony. The partnership between SwAM and SGU was particularly important because SGU possesses technical competence and resources not found within SwAM. This collaboration was also made possible by a trust relationship between the person responsible for MSP at SwAM and a senior official at SGU, which enabled a fruitful collaboration that significantly strengthened Symphony. Involving SGU in the development of Symphony was key to its amplification, because it offered the SwAM network complementary knowledge and technical expertise related to cumulative impact assessments, and data collection and management. From late 2015 until 2017, a small number of SGU staff became part of the network of SwAM staff in the scoping and data collection process. SGU staff were asked to evaluate existing data sources, establish quality and technical requirements, and prepare data layers (i.e. maps). SGU also supported the consultant who started developing the Symphony tool in December 2017, and was called in to help with improving the tool and fixing data errors that were discovered when the Symphony tool was used for preparing the systematic environmental assessments of the second and third drafts of the national marine spatial plans.

Strategic action, resource mobilization, leadership, and willingness to learn and experiment with new knowledge were also key drivers during the replication and further stabilization, and transferring phases of the Symphony amplification process. The idea of applying for research funding for the ClimeMarine project was formed after an informal discussion between the head of MSP at SwAM and the head of the Oceanographic Unit at the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) about the importance of including climate change science in MSP. This discussion led to a successful SMHI-led application for research funding for the ClimeMarine project in 2017. Importantly, the ClimeMarine project ensured that members of the small network of staff from SwAM and SGU could continue working on the Symphony tool independently of the development of MSP. By including climate change science, the ClimeMarine project also increased the potential of the Symphony tool to be used for climate change scenario-based MSP in the future.

Institutional barriers

The innovation and learning process in the development of the Symphony tool also met with several institutional challenges. At the early stage of the stabilizing phase between late 2015 and late 2017, the intention was to develop the Symphony tool to support the development of the second draft of the marine spatial plans during 2017. At a bilateral meeting with partners at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2015, SwAM staff were introduced to a cumulative impact assessment software named SeaSketch, which was later identified as a promising and easy-to-tailor platform for Symphony. SeaSketch was invited for collaboration, following a procurement procedure.

However, work on the Swedish SeaSketch version was soon discontinued by SwAM management due to legal concerns about software ownership and requirements of EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as user data within SeaSketch was at the time stored outside of the EU. For this reason, and due to technical difficulties in creating a proprietary version, the development of the Symphony tool took longer than expected. Thus, the SeaSketch-based Symphony was not used as intended in the development of the second draft of the marine spatial plans. Instead, the consultants’ Symphony tool was hastily put together and used for the second and third draft of the marine spatial plans and for the development of the strategic environmental assessment. Due to the legal barriers, the critical window of opportunity in the MSP process was thus partially missed, with consequences for the stabilization of Symphony.

Another institutional factor, which affected the replication process in particular, relates to challenges in bridging across multiple governance levels. Notes taken during stakeholder workshops in the ClimeMarine project suggest that Swedish coastal municipalities and county administrative boards show a keen interest in Symphony and see large potential value in the method as a planning tool, and typically lack resources to develop such advanced planning tools themselves. However, the data currently included in Symphony does not match their needs in terms of spatial resolution of data on ecosystem components and human pressures. Stakeholders voiced similar concerns when asked about adding data about habitat connectivity and the impact of different climate change scenarios on ecosystem components in Symphony. They also opined that the level of uncertainty about future climate change and impacts was too high. Availability and accessibility of data from Symphony were also of key importance to stakeholders. Chiefly, they asked for the opportunity to upload their own data to the system. However, there are legal restrictions imposed on publishing proprietary data, which pose obstacles—though not insurmountable—for local governments to upload data to Symphony. Several of the stakeholders’ concerns have been taken into account within the ClimeMarine project, and research on e.g. connectivity are published (Jonsson et al. 2021), while high-resolution modelling and connectivity in a future climate are ongoing. Uploading new data to Symphony, however, remains to be handled in future development.

While these issues related to the appropriateness of data can be seen as a natural consequence when a decision-support tool is amplified to be used in a different context, the mismatch between current data and local stakeholders’ needs can also partly be explained by institutional mandates, priorities, and limited coordination across governance levels (see e.g. Sandström et al. 2020 for a discussion). Indeed, as SwAM has an institutional mandate and funding to support national-level marine management, Symphony was developed to fit the needs of the national MSP process, with no system in place for other actors to use the tool. Taking into account the needs of municipalities and county boards at an early stage of development would likely have simplified the process of tailoring Symphony to their needs.

Another institutional factor that affected the development and amplification of the Symphony tool was the decision by SwAM management in 2017 for a comprehensive staff restructuring. This led to the reassignment of the originator of the Symphony idea, from the unit for MSP to the unit for the marine environment. According to interviews, the intention with the relocation was that the Symphony tool could also be developed for implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). This would greatly expand the scope and relevance of Symphony beyond the MSP process. However, repurposing Symphony for the Marine Strategy Framework Directive would require significant further development and the inclusion of suitable indicators to assess if Good Environmental Status of marine waters has been achieved or maintained. This development has not been prioritized by SwAM in the Marine Strategy Framework Directive implementation, as other tools are currently used for MSFD reporting. In practice, the main impact of the reassignment has instead been that the small network that had been driving the development of Symphony was no longer in one unit, which made working together more difficult. The reassignment, combined with the MSP process coming to a close, thus constituted an institutional challenge for Symphony in terms of its stabilization internally at SwAM. Unreliable funding and divided ownership of the Symphony tool had also become issues after the final draft of the marine spatial plans was submitted to the Swedish government in December 2019. Funding for the development of Symphony to support national and local decision-making was then reduced. In turn, work to amplify Symphony’s impact became reliant on funding from research projects like ClimeMarine, and SwAM’s international development work, with only a modest budget for maintenance. It is also not clear if, how, and when Symphony will be used for the monitoring of the MSP directive or for the implementation of other national or EU legislation related to ecosystem-based management such as the Water Framework Directive or the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, although this will be clarified during an ongoing overhaul of SwAM’s data, information, and tool structure.

Despite these institutional challenges, the network has persisted and has continued collaboration on a formal and informal basis, working with different aspects of amplification and continuing the work to strengthen Symphony’s position internally and externally. Notably, the successful replication process where Symphony is promoted internationally has built credibility and strengthened its position internally as well.

Discussion

In this study, we found evidence that informal networks worked as “shadow spaces” (Pelling et al. 2008) that allowed experts at SwAM to develop the Symphony tool by learning and experimenting with the cumulative impact assessment methodology.

Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of strategic agency (Westley et al. 2013) for the amplification of sustainability initiatives. Findings suggest that the ability of members of the small network of SwAM staff members to mobilize financial resources and build relationships within the agency, among other agencies, and among experts based on mutual learning and trust were key factors throughout the inception and stabilization phases of the Symphony tool development. Critically, the network members played complementary roles in this process, including a manager mobilizing funding and ensuring a protected space for innovation, a visionary and knowledgeable expert leading the development, and a practitioner championing the uptake. Supporting earlier research on strategic agency (Westley et al. 2013), we found that coalition forming, resource mobilization, leadership, and willingness to learn and experiment were also crucial during the replication and further stabilization phase as well as the transferring phase of the Symphony amplification process. Insights from the development of Symphony also align with the study of Charli-Joseph et al. (2018), who have pointed out the importance of shared values and objectives for collective action for sustainability initiatives and transformative change.

This study has shown that social learning can galvanize action towards ecosystem-based MSP. We found that social learning was a driving force in the inception and amplification phases of the Symphony tool. Results also show that the learning process became more complex and institutionalized as Symphony went through its different development stages. During the inception phase, the development of Symphony was driven by an informal network of SwAM experts. More stakeholders got involved and their involvement was increasingly formalized as Symphony was used for the development of MSP and was eventually replicated in the ClimeMarine project and transferred through SwAM’s international development cooperation. These findings resonate with research on social learning outcomes, which has pointed out that social learning can lead to concerted action and improve the capacity of networks to amplify the impact of sustainability initiatives across governance levels (Suškevičs et al. 2018). Our research also suggests that trust, leadership, and resource mobilization skills drive social learning and enhance the capacity of networks to amplify the impact of a specific sustainability initiative on marine governance.

This study also supports earlier research on the importance of institutional context to transformative change in marine governance (Kelly et al. 2018; Westley et al. 2013). Specifically, we found evidence that the network of key individuals strategically seized a window of opportunity, which opened up when MSP was introduced as a novel marine management instrument. However, unexpected legal issues barred the adoption of an already existing planning tool easily adopted for cumulative impact assessment. This hampered the development process of Symphony significantly. As the MSP process ended, the institutional context changed, with reduced financial resources and uncertain long-term institutional support as a consequence. A staff restructuring seemingly presented institutional opportunities to further embed Symphony in the organization and expand its scope to also be used in the agency’s work on the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. This opportunity, however, did not materialize and rather appears to have hampered the stabilization of Symphony, as the tool has still not been developed in this direction.

Experiences with the Symphony tool also highlight the difficulties of sustainability initiatives to trigger transformative change across multiple levels of governance. While our research shows that the Symphony tool was successfully used to support ecosystem-based MSP at the national level, efforts to develop the tool to achieve the same at the local level have, thus far, been less successful. This can partly be explained by the idiosyncrasy of the Swedish marine governance system which gives municipalities planning competence regarding their own part of the territorial sea. Westholm (2018) has pointed out that national and local authority over marine planning is overlapping and inconsistent. Thus, the challenges associated with using Symphony at the local level are in part a cause of limited coordination across national and local governance levels. In addition, our research shows that the different use cases of the Symphony tool—supporting national and local work on MSP, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, and international development—demand significant financial resources, human capacity, and coordination. The different applications also ask for different types of data and information, methodologies for knowledge creation, and levels of competence among developers and users. This resonates with previous research on amplification across scales, which may require significant changes to the original innovation to meet the needs of a different context (Westley and Antadze 2010; Moore et al. 2014). Indeed, it highlights the challenges involved in achieving transformative change in multilevel governance systems.

While it was beyond the scope of this study to systematically assess whether Symphony has contributed to improved decision-making or healthier ecosystems, it appears as though it has made a contribution towards more ecosystem-based marine governance by introducing a holistic, ecosystem-based and data-driven element. Despite a range of institutional barriers, Symphony has been put into use in Sweden, and has inspired similar initiatives globally. Whether these impacts will last over time, and whether more transformational changes will appear, remains to be seen and will likely require the coalescence of a range of other sustainability initiatives driven by a multitude of actors, across different levels of the governance system.

Our research also contributes insights into the difficulties of expanding the scope of decision-support tools to include climate change-related information, particularly at the local level. In line with Klein and Juhola’s (2013) research on the gap between climate adaptation research and action, experiences with integrating climate information in Symphony show that meeting stakeholders’ requirements for high-resolution information with limited uncertainty continues to be a main challenge for projects aiming to provide science-based support for adaptation action. However, stakeholder workshops also revealed that the resolution of the model data may be less important than perceived, and may be addressed through appropriate communication of climate change research and its system of uncertainties (Arneborg et al. forthcoming). These findings are in line with other research (Cash et al. 2003; Dilling and Lemos 2011; West et al. 2021), which emphasizes the importance of the credibility, salience, legitimacy, usefulness and usability of environmental science and the importance of stakeholder involvement in knowledge co-production processes to bridge the knowledge–action gap. Our research confirms that availability and accessibility of knowledge are indeed key criteria for successful uptake of climate change science by decision-makers. Making the Symphony data publicly available from the start is a step in this direction, as is the open-source version of Symphony.

As illustrated by this study, the typology developed by Lam and colleagues (2020) is useful as a comprehensive conceptual framework to unpack various strategies for amplification of sustainability initiatives. We found that the amplification processes are overlapping rather than discrete, both temporally and in the sense that they may feed into and enable each other. For instance, progress in one type of amplification process (e.g. international transfer) may build credibility and legitimacy that improves the prospects for progress in other amplification processes (e.g. internal stabilization). It can also help maintain momentum for an initiative in the face of institutional barriers. However, as illustrated by this study, Lam et al.’s (2020) framework provides limited insights into the mechanisms at play in amplification processes, and can therefore be fruitfully complemented by analyses of strategic agency, learning, and institutional context to better capture the dynamics of transformative change.

For change agents and practitioners seeking transformative change towards sustainability, the Symphony experience offers some useful lessons. Importantly, the central network contained motivated individuals that shared a similar vision, and who had complementary skills and roles. Despite being a small team, they were able to raise funding, innovate and develop the idea, and implement it and test it in practice. It also allowed them to work on several fronts in parallel (i.e. applying several amplification strategies of stabilizing, replicating and transferring), which has increased impact and provided opportunities to the initiative to overcome institutional barriers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has shown the potential and challenges of sustainability initiatives to promote deliberative transformative change in marine governance systems. The various types of amplification processes involved in increasing the impact of a sustainability initiative can be both overlapping and interdependent. Experience with the Symphony tool highlights that understanding the mechanisms at play in amplification processes requires an analysis of the interplay between strategic agency, social learning, and institutional context. A key challenge in amplification across governance scales is the need for significant adjustments of the original innovation to meet differing needs and competences. This highlights the broader challenge of achieving transformative change across scales in heterogenous and fragmented multilevel governance systems. Co-production of knowledge and early consideration of stakeholder needs to ensure accessibility and availability could improve the chances of successful amplification.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arneborg L, Brunnabend SB et al (forthcoming) Modelling of complex coastal systems. Comparison of two model approaches

Auschra C (2018) Barriers to the integration of care in inter-organisational settings: a literature review. Int J Integr Care 18(1):5

Bebbington A (1999) Capitals and capabilities: a framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Dev 27(12):2021–2044

Bennett EM, Solan M, Biggs R, McPhearson T, Norström AV, Olsson P et al (2016) Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Front Ecol Environ 14(8):441–448

Bodin Ö, Crona BJ (2008) Management of natural resources at the community level: exploring the role of social capital and leadership in a rural fishing community. World Dev 36(12):2763–2779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.12.002

Cash DW, Clark WC, Alcock F, Dickson NM, Eckley N, Guston DH, Jäger J, Mitchell RB (2003) Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100(14):8086–8091. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1231332100

Charli-Joseph L, Siqueiros-Garcia JM, Eakin H, Manuel-Navarrete D, Shelton R (2018) Promoting agency for social-ecological transformation. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10214-230246

Dilling L, Lemos MC (2011) Creating usable science: opportunities and constraints for climate knowledge use and their implications for science policy. Glob Environ Change 21(2):680–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.11.006

Dorado S (2005) Institutional entrepreneurship, partaking, and convening. Organ Stud 26(3):385–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050873

Duarte CM, Agusti S, Barbier E, Britten GL, Castilla JC, Gattuso J-P, Fulweiler RW et al (2020) Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580(7801):39–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2146-7

Ducrot R (2009) Gaming across scale in peri-urban water management: contribution from two experiences in Bolivia and Brazil. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol 16(4):240–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500903017260

EC, European Commission (2014) Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014, establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning 2014/89/EU. Off J Eur Union 257:135–145

Ehnert F, Frantzeskaki N, Barnes J, Borgström S, Gorissen L, Kern F, Strenchock L, Egermann M (2018) The acceleration of urban sustainability transitions: a comparison of Brighton, Budapest, Dresden, Genk, and Stockholm. Sustainability 10(3):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030612

Enqvist JP, West S, Masterson VA, Haider LJ, Svedin U, Tengö M (2018) Stewardship as a boundary object for sustainability research: linking care, knowledge and agency. Landsc Urban Plan 179:17–37

Fernandes ML, Esteves TC, Oliveira ER, Alves FL (2017) How does the cumulative impacts approach support maritime spatial planning? Ecol Indic 73(February):189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.09.014

Foley MM, Halpern BS, Micheli F, Armsby MH, Caldwell MR, Crain CM, Prahler E et al (2010) Guiding ecological principles for marine spatial planning. Mar Policy 34(5):955–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.02.001

Glaser M, Baitoningsih W, Ferse SCA, Neil M, Deswandi R (2010) Whose sustainability? Top–down participation and emergent rules in marine protected area management in Indonesia. Mar Policy 34(6):1215–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.04.006

Gorissen L, Spira F, Meynaerts E, Valkering P, Frantzeskaki N (2018) Moving towards systemic change? Investigating acceleration dynamics of urban sustainability transitions in the Belgian City of Genk. J Clean Prod 173:171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.052

Gunderson L (1999) Resilience, flexibility and adaptive management—antidotes for spurious certitude? Ecol Soc 3(1):7

Halpern BS, Walbridge S, Selkoe KA, Kappel CV, Micheli F, D’Agrosa C, Bruno JF et al (2008) A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319(5865):948–952. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1149345

Halpern BS, Frazier M, Afflerbach J, Lowndes JS, Micheli F, O’Hara C, Scarborough C, Selkoe KA (2019) Recent pace of change in human impact on the world’s ocean. Sci Rep 9(1):11609. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47201-9

Hammar L, Molander S, Pålsson J, Schmidtbauer Crona J, Carneiro G, Johansson T, Hume D et al (2020) Cumulative impact assessment for ecosystem-based marine spatial planning. Sci Total Environ 734(September):139024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139024

HaV, Havs-och vattenmyndigheten (2012) Tilläpning Av Ekosystemansatsen i Havsplaneringen. Havs-och vattenmyndigheten, Gothenburg, Sweden

HaV, Havs-och vattenmyndigheten (2015) Havsplanering-nuläge 2014: statlig planering i territorialhav och ekonomisk zon. Havs-och vattenmyndigheten, Gothenburg, Sweden

HaV, Havs-och vattenmyndigheten (2016) Färdplan Havsplanering. Havs-och vattenmyndigheten, Gothenburg, Sweden

HaV, Havs-och vattenmyndigheten (2018) Symphony Integrerat planeringsstöd för statlig havsplanering utifrån en ekosystemansats. Havs-och vattenmyndighetens rapport 2018:1. Havs-och vattenmyndigheten, Gothenburg, Sweden

HaV, Havs-och vattenmyndigheten (2019) Havs-Och Vattenmyndighetens Program För Internationellt Utvecklingssamarbete. Dnr 666–19. Havs och vattemyndigheten, Gothenburg, Sweden. https://www.havochvatten.se/download/18.ffe12416a55627280cc6c7/1557384777161/program-internationellt-utvecklingssamarbete-2019-2022.pdf

HaV, Havs-och vattenmyndigheten (2022) Havsplaner för Bottniska viken, Östersjön och Västerhavet. Statlig planering i territorialhav och ekonomisk zon. https://www.havochvatten.se/download/18.5a0266c017f99791d0e68c2b/1648118007165/Havsplaner-beslutade-2022-02-10.pdf

Havsplaneringsutredning (2010) Planering På Djupet—Fysisk Planering Av Havet. Statens Offentliga Utredningar 2010:91. Regeringskansliet, Stockholm. https://www.regeringen.se/49bba9/contentassets/0184e97c4f7d417b90732bf74e7833b4/planering-pa-djupet-fysisk-planering-av-havet-sou-201091

Hermans F, Roep D, Klerkx L (2016) Scale dynamics of grassroots innovations through parallel pathways of transformative change. Ecol Econ 130(October):285–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.07.011

Järnberg L, Kautsky EE, Dagerskog L, Olsson P (2018) Green niche actors navigating an opaque opportunity context: prospects for a sustainable transformation of Ethiopian agriculture. Land Use Policy 71:409–421

Jonsson PR, Hammar L, Wåhlström I, Pålsson J, Hume D, Almroth-Rosell E, Mattsson M (2021) Combining seascape connectivity with cumulative impact assessment in support of ecosystem-based marine spatial planning. J Appl Ecol 58(3):576–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13813

Kelly C, Ellis G, Flannery W (2018) Conceptualising change in marine governance: learning from transition management. Mar Policy 95(September):24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.023

Kingdon JW (1995) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Harper Collins College Publishers, New York, NY, USA

Klein RJT, Juhola S (2013) A framework for nordic actor-oriented climate adaptation research. NORD-STAR working paper 2013–1. Nordic Centre of Excellence for Strategic Adaptation Research. http://nord-star.info/attachments/article/125/NORD-STAR-WP-2013-01-Klein-Juhola.pdf

Lam DPM, Martín-López B, Wiek A, Bennett EM, Frantzeskaki N, Horcea-Milcu AI, Lang DJ (2020) Scaling the impact of sustainability initiatives: a typology of amplification processes. Urban Transform 2(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-020-00007-9

Lebel L, Grothmann T, Siebenhüner B (2010) The role of social learning in adaptiveness: insights from water management. Int Environ Agreements Politics Law Econ 10(4):333–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9142-6

Moore ML, Tjornbo O, Enfors E, Knapp C, Hodbod J, Baggio JA et al (2014) Studying the complexity of change: toward an analytical framework for understanding deliberate social-ecological transformations. Ecol Soc 19:4

Moore ML, Riddell D, Vocisano D (2015) Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. J Corporate Citizenship 2015(58):67–84. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2015.ju.00009

Naber R, Raven R, Kouw M, Dassen T (2017) Scaling up sustainable energy innovations. Energy Policy 110:342–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.07.056

Olsson P, Folke C, Hahn T (2004) Social–ecological transformation for ecosystem management: the development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in southern Sweden. Ecol Soc 9(4):2

Olsson P, Galaz V, Boonstra WJ (2014) Sustainability transformations: a resilience perspective. Ecol Soc 19(4):art1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06799-190401

Österblom H, Gårdmark A, Bergström L, Müller-Karulis B, Folke C, Lindegren M, Casini M et al (2010) Making the ecosystem approach operational—can regime shifts in ecological- and governance systems facilitate the transition? Mar Policy 34(6):1290–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.05.007

Pahl-Wostl C (2002) Towards sustainability in the water sector—the importance of human actors and processes of social learning. Aquat Sci 64(4):394–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00012594

Pahl-Wostl C (2009) A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob Environ Change 19(3):354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001

Pelling M, High C, Dearing J, Smith D (2008) Shadow spaces for social learning: a relational understanding of adaptive capacity to climate change within organisations. Environ Plan A 40(4):867–884. https://doi.org/10.1068/a39148

Pereira L, Frantzeskaki N, Hebinck A, Charli-Joseph L, Drimie S, Dyer M, Eakin H et al (2020) Transformative spaces in the making: key lessons from nine cases in the global South. Sustain Sci 15(1):161–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00749-x

Rao H (1998) Caveat emptor: the construction of nonprofit consumer watchdog organizations. Am J Sociol 103(4):912–961

Reed MS, Evely AC, Cundill G, Fazey I, Glass J, Laing A, Newig J et al (2010) What is social learning? Ecol Soc 15(4):1–10

Rotmans J, Loorbach D (2008) Towards a better understanding of transitions and their governance: a systemic and reflexive approach. In: Grin J, Rotmans J, Schot J (eds) Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge, London, pp 104–220

Sandström A, Söderberg C, Lundmark C, Nilsson J, Fjellborg D (2020) Assessing and explaining policy coherence: a comparative study of water governance and large carnivore governance in Sweden. Environ Policy Govern 30(1):3–13

Suškevičs M, Hahn T, Rodela R, Macura B, Pahl-Wostl C (2018) Learning for social-ecological change: a qualitative review of outcomes across empirical literature in natural resource management. J Environ Plan Manage 61(7):1085–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1339594

Valkering P, Yücel G, Gebetsroither-Geringer E, Markvica K, Meynaerts E, Frantzeskaki N (2017) Accelerating transition dynamics in City regions: a qualitative modeling perspective. Sustainability 9:1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071254

Wåhlström I, Hammar L, Hume D, Pålsson J, Almroth-Rosell E, Dieterich C, Arneborg L, Gröger M, Mattsson M, Zillén Snowball L, Kågesten G, Törnqvist O, Breviere E, Brunnabend S-E, Jonsson PR (2022) Projected climate change impact on a coastal sea—as significant as all current pressures combined. Glob Change Biol 28(17):5310–5319. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16312y

West JJ, Järnberg L, Berdalet E, Cusack CK (2021) Understanding and managing harmful algal bloom risks in a changing climate: lessons from the European CoCliME project. Front Clim 3:636723. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.636723

Westholm A (2018) Appropriate scale and level in marine spatial planning – management perspectives in the Baltic Sea. Mar Policy 98(December):264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.021

Westley F (2002) Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and natural systems theories for sustainable future. In: Gunderson LH, Holling CS (eds) Devil in the dynamics. Island, Washington, DC, USA, pp 333–360

Westley F, Antadze N (2010) Making a difference: strategies for scaling social innovation for greater impact. Innov J 15(2):Article 2

Westley F, Zimmerman B, Patton MQ (2006) Getting to maybe: how the world is changed. Random House, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Westley F, Tjornbo O, Schultz L, Olsson P, Folke C, Crona B, Bodin Ö (2013) A theory of transformative agency in linked social–ecological systems. Ecol Soc 18(3):art27. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05072-180327

Withycombe LK, Wiek A, Lang DJ, Yokohari M, van Breda J, Olsson L, Ness B et al (2016) Utilizing international networks for accelerating research and learning in transformational sustainability science. Sustain Sci 11(5):749–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0364-6

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the interviewees involved in this study.

Funding

This research was carried out within the projects CoCLiME and ClimeMarine. CoCliME is part of ERA4CS, an ERA-NET initiated by JPI Climate, and funded by EPA (IE), ANR (FR), BMBF (DE), UEFISCDI (RO), RCN (NO), and FORMAS (SE), with co-funding by the European Union (Grant 690462). ClimeMarine is funded through the Swedish Research Council Formas within the framework of the National Research Program of Climate (grant no. 2017-01949).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handled by Sergio Rosendo, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Järnberg, L., Vulturius, G. & Ek, F. Strategic agency and learning in sustainability initiatives driving transformation: the symphony tool for ecosystem-based marine spatial planning. Sustain Sci 18, 1149–1161 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01286-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01286-w