Abstract

Solutions that engage the public are needed to tackle air pollution. Technological approaches are insufficient to bring urban air quality to recommended target levels, and miss out on opportunities to promote health more holistically through behavioural solutions, such as active travel. Behaviour change is not straightforward, however, and is more likely to be achieved when communication campaigns are based on established theory and evidence-based practices. We systematically reviewed the academic literature on air pollution communication campaigns aimed at influencing air pollution-related behaviour. Based on these findings, we developed an evidence-based framework for stimulating behaviour change through engagement. Across the 37 studies selected for analyses, we identified 28 different behaviours assessed using a variety of designs including natural and research-manipulated experiments, cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys and focus groups. While avoidance behaviour (e.g. reducing outdoor activity) followed by contributing behaviours (e.g. reducing idling) were by far the most commonly studied, supporting behaviour (e.g. civil engagement) shows promising results, with the added benefit that supporting local and national policies may eventually lead to the removal of social and physical barriers that prevent wider behavioural changes. Providing a range of actionable information will reduce disengagement due to feelings of powerlessness. Targeted localized information will appear more immediate and engaging, and positive framing will prevent cognitive dissonance whereby people rationalize their behaviour to avoid living with feelings of unease. Communicating the co-benefits of action may persuade individuals with different drivers but as an effective solution, it remains to be explored. Generally, finding ways to connect with people’s emotions, including activating social norms and identities and creating a sense of collective responsibility, provide promising yet under-explored directions. Smartphones provide unique opportunities that enable flexible and targeted engagement, but care must be taken to avoid transferring responsibility for action from national and local authorities onto individuals. Multidisciplinary teams involving artists, members of the public, community and pressure groups, policy makers, researchers, and businesses, are needed to co-create the stories and tools that can lead to effective action to tackle air pollution through behavioural solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Air pollution is the fourth highest risk factor for premature death globally, sitting only behind high blood pressure, smoking and diet (The Health Effects Institute 2017). The World Health Organization estimates that 4.2 million people die prematurely because of ambient air pollution each year (World Health Organization (WHO) 2018). Research also links air pollution to premature births, impaired cognitive and lung developments and increased risk of respiratory illnesses, diabetes, cancers, strokes and dementia (Kelly and Fussell 2015; Royal College of Physicians 2016; World Health Organization 2013). Despite efforts to improve air pollution, 92% of the world’s population live in areas that exceed current World Health Organization standards (The World Health Organization 2018). Effective ways of reducing both air pollution concentration and the public’s exposure to it are required to prevent a public health crisis.

To date, research and policy have focused on regulations and technological solutions to urban air pollution, with limited results (Giardullo et al. 2016). While solutions such as electrification of the vehicle fleet will likely play a role in cleaning up our urban environments, more attention could be paid to the win–win potential for behaviour change to reduce both overall concentrations of air pollution and the public’s exposure. Encouraging a reduction in driving and a shift towards active travel (such as walking, cycling) for example, can improve air quality in urban areas (Johansson et al. 2017; Shapiro et al. 2002) and lead to further co-benefits such as increase in physical activity and reduction in carbon emissions (Rojas-Rueda et al. 2012, 2011; Woodcock et al. 2009). Co-benefits such as these, often absent from technological solutions, help strengthen the case to develop and implement policies aimed at changing public behaviour.

Changing the public’s behaviour, however, is not straightforward. The drivers of human behaviour are complex and are at once individual, economic, social, environmental, cultural and contextual. Various theories have been developed to explain, predict and influence behaviour; contributions from economists, psychologists, sociologists, neurologists and anthropologists make behavioural science a highly interdisciplinary subject area. Approaches from social psychology emphasise the importance of factors related to the individuals, such as norms, identity, roles, self-efficacy, attitudes, intentions and belief, to name a few (Ajzen 1991; Bandura 1999; Becker 1974; Prochaska et al. 2008; Rosenstock 1974). Approaches from behavioural economics start from an understanding of the individual as a rational decision-maker and utility maximiser, with action or inaction resulting from a weighing up of the costs and benefits of outcomes (De Dios Ortuzar et al. 1998). Some highlight the role of automatic and emotive decision-making processes over rationality (Kahneman 2011). Another approach, social practice theory, sets routine or habitual behaviour in the midst of interwoven relationships between “materials” (e.g. infrastructure, technologies), “competence” (skills, know-how), and “meanings” (norms, expectations, culture) (Welch 2017; Shove 2010). Individuals in this context are seen as practitioners acting within this web of inter-relationships, and should be understood and engaged within the context in which they act (Welch 2017).

Governments can shape in part the contextual environment through: (i) ‘hard’ policies to affect public behaviour include the implementation of driving and parking restrictions, low emission zones or tax increases on more polluting vehicles; (ii) ‘soft’ policies targeting behaviour change include public communication, social marketing or education campaigns. Whereas the former are more coercive, the latter depend on voluntary changes in behaviour made desirable through increased awareness and education. Public communication has been shown to stimulate engagement and behaviour change in a range of contexts from smoking cessation, meat and alcohol consumption and sex-related behaviours (Wakefield et al. 2010) to environmental and climate-related behaviours such as energy consumption (Whitmarsh et al. 2012). A review of over 100 public communication campaigns finds they are effective tools, especially in contexts where social institutions and norms make harder approaches less desirable (Weiss and Tschirhart 2006).

Communicating to the public about air pollution is often used by local and national authorities to inform and change public attitudes and behaviours. At the very least, governments may adopt air quality indices (AQI) to report and communicate on the state of air quality to members of the public (WHO 2020). Some areas develop more targeted campaigns, most commonly alert systems to warn members of the public—particularly at-risk individuals—when high air pollution episodes occur. These are typically meant to discourage outdoor activities, or, to a lesser extent, to reduce car use. Environmental pressure groups, community organizations, health care professionals, schools and universities represent other sources of air pollution information, communicated across channels from social media to exhibitions. The multitudes of schemes are rarely evaluated, however, and we know little about the specific characteristics that make for effective schemes, or about best practice for air pollution communication. Whilst a recent paper summarises the barriers and enablers to behaviour change in relation to adherence to air pollution alerts (D’Antoni et al. 2017), to our knowledge there is no systematic review of the approaches and methods used to effectively communicate on air pollution so the public engages and changes behaviours in desired ways.

Recognising these gaps, this paper makes two contributions to the literature:

-

(1)

A systematic literature review of the approaches used to communicate air pollution to the public with the aim of influencing their behaviour;

-

(2)

An evidence-based framework for stimulating behaviour change through engagement, supported by the literature review.

Methods

Search strategy

In June 2018, we searched the Web of Science Core Collection, which includes a variety of databases with publications across disciplines, including the sciences, social science, arts and humanities (e.g. the Science Citation Index Expanded and the Social Sciences Citation Index), to identify articles relating to air pollution, public communication and behaviour change. We did not apply a date limit or study type restriction. To identify a comprehensive set of search terms (Table 1), we used an iterative process whereby we checked that the search terms were picking up pre-identified seminal works in the field. Two researchers [RR and PC] independently undertook the screening process of the search results and discussed any discrepancies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all study designs and only peer-reviewed articles published in English. Articles were included if they met the four criteria outlined in Table 2, i.e. they reported on air pollution communication and related behaviours. Specifically, we excluded studies that analysed only air pollution information campaigns and perceptions and attitudes in response to public information, but neglected to discuss the effects on behaviour. We did not exclude literature reviews from the literature search as they provide additional perspectives for the discussion, however, these were not analysed in the descriptive account of the literature in the results section.

Risk of bias

Given the huge variety of study designs and context, we opted for a qualitative review of the literature and erred on the side of inclusiveness for all study types. For the more quantitative studies, however, we screened papers for risk of bias based on the same approach as a recent systematic review on a similar topic (D’Antoni et al. 2017). Papers were excluded if there were indications of risks in selection bias (e.g. poor reporting of target population and sample size), detection bias (e.g. poor definition of outcome), reporting bias (e.g. confidence intervals not reported), or other biases (unclear research question). Two researchers [RR and PC] independently analysed papers for risk of bias and discussed any discrepancies.

Data review

We developed a data extraction framework of study characteristics (date, author, country, study type, design, sample size, general context, behaviour type, measure and evidence of change; see Table 3. Based on Berlo’s Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver (SMCR) model of effective communication (Berlo 1960), we also extracted: message content, channel, source of information and characteristics of the receiver (see Appendix Table A1). We chose this extraction framework as it fit many of the studies’ reporting and common practices in communications, but our critical evaluation highlights the need to incorporate constructs beyond this framework.

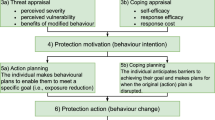

Proposed engagement framework

Building on our findings on effective engagement approaches and on an evaluation of research gaps presenting promising opportunities, we developed a framework and recommendations for future air pollution communication and engagement interventions. We structured the engagement framework based on a combination of the SMCR model and the Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour (COM-B) and its associated guidelines for designing and developing behavioural interventions: the Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al. 2011). COM-B proposes that behaviours result from interactions between an individual’s psychological and physical capability, their automatic and reflective motivation and the presence of a social or physical opportunity. Through a critical review of the literature we identify components of communication approaches demonstrated as effective, and areas that are theoretically promising or have been shown to be effective in other context but have been insufficiently evaluated so far. Our framework also highlights limitations of a focus on communication and dependencies with other approaches—in line with the Behaviour Change Wheel and other theories such as the socio-ecological model (Stokols 1992) and social practice (Welch 2017), which recognize explicitly inter-dependencies between social, physical and individual contexts.

Results

We identified 4324 studies in Web of Science Core Collection. We removed: 4119 as either duplications or non-eligible based on reading titles and abstracts; a further 156 based on our eligibility criteria and a full reading; 7 due to risk of bias. This left 42 studies to be included in the review (see flow diagram in Fig. 1). Five studies are reviews (D’Antoni et al. 2017; Hubbell et al. 2018; Kelly et al. 2012; Kelly and Fussell 2015; Vardoulakis et al. 2018). The reviews are not included in the following results section to avoid double-counting; instead, we bring them into the discussion section.

We describe briefly the selected studies in the next section, including study characteristics, context and evidence of behaviour change, followed by more detailed recount of the studies along the dimensions of the SMCR model of effective communication (see “Methods” section). We then bring a broader literature base to elaborate our recommendations in the “Discussion” section.

We first provide an overview of study characteristics (methods, sample size, etc. Table 3), then present results along the SMCR dimensions (Appendix Table A1). We critically analyse the literature in the “Discussion” section to formulate recommendations.

Studies’ characteristics

Most studies on air pollution communication were conducted in the USA (18), four in the UK, four in Canada, two in Iran, Italy and Spain, one each for Australia, Chile, Denmark, France and Mexico, and five take an international focus. Publication dates range from 1991 to 2018, with a steady increase throughout the period (Appendix Figure A1).

We categorized study designs as: cross-sectional (surveys, interviews or focus groups, or a mix, collecting data at one point-in-time); repeated cross-sectional (e.g. panel data collected over different points in time with different samples); natural experiment (control and experimental conditions are determined by ‘nature’ or by factors outside the researchers’ control); experimental design (factors and variables have been manipulated by researchers); or review of the literature (See Table 3 for details of each study).

All the natural experiments (14 studies) investigated how the public respond to air pollution alerts (a.k.a. pollution advisories) issued by local and national authorities when air pollution is forecast to be high. To measure behaviour change between days when alerts are issued and other days, most of these studies used large datasets of existing longitudinal or repeated cross-sectional data (e.g. census, turnstile for park entry, traffic counts), others used bespoke surveys with self-reported behaviour change, and two only inferred behaviour change from a reduction in pollution.

While six of the cross-sectional studies were also concerned specifically with the use of AQI and advisories, and another about how media coverage of air pollution affected behaviours, most of these explored the role of pollution-related information through surveys and interviews how general knowledge about air pollution affects behaviours or intentions to change behaviours. Many of these studies were undertaken in the context of informing air pollution management and engagement activities. One study, for example, assessed the specific type of travel information respondents would value to guide behaviours (Daher et al. 2018), two interviewed stakeholders on the development of a health-based AQI (Cole et al. 1999; Radisic and Newbold 2016), a community-led programme collected views for an anti-idling campaign (Eghbalnia et al. 2013). Insights and interests in local AP information were also evaluated in the context of website and app development (Mason et al. 2017), and community-based sensor developments (Hsu et al. 2017).

The six experimental design studies provided more direct evaluations of various elements of communication and engagement on behaviours. Similar to some of the cross-sectional studies, most of these were developed in the context of testing specific aspects of communication and engagement strategies. Framing of messages, such as negative or positive framing on speeding (Delhomme et al. 2010), altruistic or self-focus of signage on idling (Meleady et al. 2017), outcome framing and psychological distance on pro-environmental behaviour (Mir et al. 2016). Sensing systems were also evaluated through experimental designs, one comparing sensors with documentary information (Oltra et al. 2017) and another in a context of an international competition for the development of participatory sensing (Sîrbu et al. 2015).

Type of behaviour

We identify 28 types of behaviours assessed across the 37 articles (Table 3). By far, the most studied behaviour was reducing outdoor activities—whether that was general reduction of time spent outdoors, or specifically reductions in vigorous exercise, park attendance, or cycling. More than two-thirds of the 23 studies on AQI or alerts assessed their impacts on reducing outdoor activities. Other types of protective or avoidance behaviours studied or mentioned included route choice to avoid busy streets, departure time to avoid peak periods, moving houses (to less polluted locations), closing windows, changing air filters, or wearing masks. All the 15 studies that targeted or mentioned behaviours meant to reduce contributions to air pollution tackled driving behaviour to a certain extent: reductions in driving, driving speed, refuelling, car sharing. A few additional contribution-type behaviours mentioned included burning wood fuels and decreasing energy consumption. Finally, three studies that were more qualitative in nature considered the potential for communication and engagement campaigns to play a role in civic engagement and supportive behaviours for policy change. These include: lobbying, education about air pollution in classrooms and the community, discussions with friends and family, signing-up for e-newsletters about environmental issues, and sending emails to local officials.

Evidence of behaviour change

Twenty-seven studies illustrated the potential for behaviour change, although many of these are ambiguous and with varying degrees of robustness of study design. Most, but not all, of the relatively large natural experiments with longitudinal observations suggest that alerts may lead to a reduction in outdoor activities. Many of the large cross-sectional surveys with self-reported behaviour change or behaviour intentions support this finding too, with notable exceptions from Lissåker et al. (2016) and Johnson (2003). Avoiding busy roads is another protective behaviour demonstrated in one large study to be impacted by AP alerts (Mirabelli et al. 2018). Reductions in contributing behaviours (i.e. driving-related) are more difficult to establish in the larger studies, but the more experimental studies with targeted or a more community-based approach find some hopeful signs, such as community-led anti-idling campaigns (Eghbalnia et al. 2013), and employer-based programs in conjunction with air-quality alerts (Henry and Gordon 2003). Civic engagement types of behaviour are qualitatively assessed mostly, but show also good potential for community-led programs, consultation processes, and accessing local information (Cole et al. 1999; Hsu et al. 2017; Mason et al. 2017).

Source of communication

Local and national authorities are the main source of air pollution communication in our selected studies (Henry and Gordon 2003; Johnson 2003; Oltra and Sala 2015; Semenza et al. 2008; Skov et al. 1991; Ward and Beatty 2016; Welch et al. 2005). Three studies using large cross-sectional survey data suggest that communication from health professionals is perceived to be a preferred source especially for ‘at risk’ groups such as asthmatics (Lissåker et al. 2016; Mirabelli et al. 2018; Wen et al. 2009). Two natural experiments, one using longitudinal observational train ridership data in Chicago and another using a repeated cross-sectional survey of 4860 participants, suggest that communication from businesses may enable employees to change commuting behaviour (Henry and Gordon 2003; Welch et al. 2005). One cross-sectional survey of 598 individuals finds that the general public prefer information from research institutes, followed by health authorities, citizens associations and municipalities (Carducci et al. 2017). A few survey- and interview-based studies also provide insights on how public trust in the source of communication is important to avoid dismissal of the information (Carducci et al. 2017; Johnson 2012; Laferriere and Crighton 2017) (Appendix Table A1).

Communication message

Insights on message content, framing and language are typically drawn from self-reported and often relatively small sample size studies, however, the diverse set of evidence reviewed provide some indication of its potential impacts on behaviour change.

Localised and context-specific information can resonate with people and their understanding of the local sources of pollution (Beaumont et al. 1999; Mason et al. 2017; Radisic and Newbold 2016). Two interview- and survey-based studies suggest that information relating to peoples’ personal habits and their everyday activities may be more likely to engage (Mason et al. 2017; Oltra et al. 2017). One experiment with 220 participants, however, tested the impact of psychological distance on intention to change behaviour and found that messages with more local information had no significant effect on behavioural response (Mir et al. 2016) (see Table A1 for more details).

Communicating the positive gains from behaviour change may be more engaging than communicating the potential losses (Beaumont et al. 1999; Blanken et al. 2001; Mir et al. 2016; Radisic and Newbold 2016). One study tested positive message framing, finding that messages such as “by mitigation of air pollution we can decrease cardiovascular and respiratory disease” may have a greater impact on intention to cycle or use public transport than negative messages such as “without mitigation of air pollution we can expect to have more cardiovascular and respiratory disease” (Mir et al. 2016). However, an experiment with a sample size of 172 found no significant impact of positive vs. negative framing on intentions to reduce driving speed (Delhomme et al. 2010).

While this finding may be culturally and location-specific, the reviewed studies (all in Anglo-Saxon contexts—UK and Canada) seemed to indicate that messages that encourage a sense of personal gain through communication of the health benefits from certain behaviours may be engaging (Beaumont et al. 1999; Radisic and Newbold 2016). A cross-sectional survey assessing views on travel-related information found that individuals expressed a preference for information on their total private travel costs, over social health-related costs or greenhouse gas social costs (Daher et al. 2018). In support of this, an experimental study with a relatively large sample of observational data found that messages encouraging a ‘private self-focus’ (via a message that reads ‘think of yourself’), reduced time spent idling more than messages that encouraged a ‘public focus’ (via an image of a ‘watching eyes’ stimulus) (Meleady et al. 2017).

Information that is too technical, unrelatable or communicates without giving context can be meaningless and unengaging (Beaumont et al. 1999; Borbet et al. 2018; Oltra and Sala 2015). Daher’s travel information survey suggests that presenting information in monetary units rather than emissions (grams of pollutant) may lead to greater intention to change transport mode (Daher et al. 2018). Other studies supporting this suggest that people are less engaged by air pollution exposure or concentrations and more by knowing what the number means for their health and what they can do about it (Beaumont et al. 1999; Oltra et al. 2017; Semenza et al. 2008).

In this regard, providing practical, actionable information relating to both exposure reduction and emissions reduction may increase self-efficacy and encourage a sense that something can be done (Beaumont et al. 1999; Teague et al. 2015; Tribby et al. 2013; Welch 2017). People express a desire for useful and practical information, particularly information that might enable engagement such as information on local environmental events or ways to send messages to elected officials (Cole et al. 1999; Hsu et al. 2017; Mason et al. 2017).

Channel of communication

The most commonly cited sources of communication are newspapers, radio, television and the internet (Beaumont et al. 1999; Blanken et al. 2001; Brown et al. 2016; Finney 2014; Oltra and Sala 2015; Ward and Beatty 2016; Welch et al. 2005; Wen et al. 2009). Other channels reported include smartphones (Jasemzadeh et al. 2018; Mason et al. 2017), face-to-face communication (Eghbalnia et al. 2013; Wen et al. 2009) and physical signage put up in public places such as by highways, bus stops, train stations, car parks and schools (Beaumont et al. 1999; Henry and Gordon 2003; Meleady et al. 2017; Vardoulakis et al. 2018). No studies have tested the impact of different communication channels on behaviour change. However, one natural experiment collecting repeated-cross-sectional survey data found greater public awareness of air pollution on days when air pollution makes headline news compared to when information is on the back pages (Henry and Gordon 2003). Two natural experiments using repeated cross-sectional survey data and observational data found no significant relationship between greater mass media coverage of air pollution and behaviour change (Carducci et al. 2017; Semenza et al. 2008).

Two studies investigated the use of mobile phones (Jasemzadeh et al. 2018; Mason et al. 2017). A randomised control trial with 130 participants found that a text messaging service encouraged protective behaviours among pregnant women (Jasemzadeh et al. 2018). A cross-sectional survey with 200 participants and additional focus groups found that respondents express a preference for an integrated data platform (such as a smartphone app) offering personalised air pollution information, weather and heat (Mason et al. 2017).

Characteristics of the receiver

People with respiratory diseases such as asthma may be more likely to engage in avoidance and protective behaviours than people who consider themselves ‘healthy’ (Johnson 2003; Lissåker et al. 2016; Mirabelli et al. 2018; Skov et al. 1991; Wen et al. 2009). A repeated cross-sectional survey found that asthmatics are more likely to report behaviour change than healthy people, but found no significant difference for people with heart disease (Mirabelli et al. 2018). Another relatively large cross-sectional survey found no significant difference in self-reported behaviour change for those with respiratory illnesses compared to those without (Borbet et al. 2018).

There is some evidence that older people are more likely to reduce outdoor activity when pollution levels are high (Lissåker et al. 2016; Noonan 2014; Ward and Beatty 2016). One natural experiment using repeated cross-sectional survey data found that people over the age of 65 reduced the amount of time spent doing vigorous outdoor activity by 82% on days when air pollution alerts have been issued, compared to 18% for the rest of the population. Another natural experiment, using repeated cross-sectional observational data of numbers of people passing a park bench, found a greater reduction in park use among older people on days when air pollution alerts are issued (Noonan 2014).

The evidence on impacts of socio-demographics are inconclusive. Some studies found that women may be more likely to change their behaviour compared to men (Brown et al. 2016; Lissåker et al. 2016; Semenza et al. 2008; Skov et al. 1991), however, a cross-sectional survey with 1100 respondents found no influence of gender on intention to change behaviour (Johnson 2003). One study suggests that lower income and educational attainment correlated with greater awareness and concern for air pollution (Semenza et al. 2008), and another study found the opposite (Lissåker et al. 2016).

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first systematic review on the approaches used to communicate air pollution to the public with the aim of encouraging voluntary behaviour change. We searched Web of Science to identify studies that investigate behaviour change in response to public communication. Overall, we found a huge diversity of study designs and context which make it difficult to provide a clear and synthetic picture of air pollution communication effectiveness. Larger studies and more robust designs tend to provide crude elements of characteristics of success (and diverging results), while smaller and more experimental and qualitative studies provide useful but less robust insights. The most studied context regards AQI and air pollution alerts, and the most commonly studied behaviour is reducing outdoor activity and exercise—with the former often but not always shown to impact the latter. Driving-related behaviours (reducing driving, idling, increasing use of sustainable transport modes) are the next most commonly studied, with diverging evidence of impacts of communication approaches. Less studied behaviours include taking less polluted routes, avoiding rush hour travel and supportive behaviours such as lobbying and civic engagement. The academic literature provides insights, mostly from self-reported and qualitative studies, on factors relating to public communication that may encourage behaviour change: messages from trusted sources such as universities, research institutes and healthcare providers may be more engaging than those from local and national government; information that is local and linked to an individual’s own daily activities may be more engaging than general information on pollution; positive framing of personal health gains is preferable over loss framing; and provision of feasible, alternative actions. Most studies rely on delivering the local air quality index in the form of general messages that inform the public when pollution forecast is high. The most commonly used communication channels are television, newspapers, radio and the internet, although the extent to which these different channels impact behaviour change and awareness requires further research. The evidence is inconclusive on the impact that the characteristics of the receiver of information has on behaviour change, although ‘at risk’ groups, such as people with asthma, cardiovascular disease and older people, seem more likely to reduce their general activity in response to air pollution alerts than healthy people.

Most of the studies in this review adopt, implicitly or explicitly, understandings of human behaviour that emphasise the importance of the individual, their attitudes, values and choices. Such approaches are referred to as ‘the portfolio model’, or ‘ABC model’ of human behaviour whereby individuals are presumed to possess a more or less stable “portfolio” of values, attitudes, norms, interests and desires, and assumed to select from them to decide on the course of action (Welch 2017). Such approaches are typical to behavioural economics and social psychology but can be seen as ‘overly simplistic, voluntaristic and individualised’ in the way they assume a linear relation between attitude, behaviour and choice (Shove 2010). Traditionally, public communication of air pollution has been driven by such understandings and has been a ‘top down keep it simple’ (Oltra and Sala 2015) approach, passing information on from experts and authorities to the general public. There have been few attempts to engage the public in the design or development of air pollution communication or to engage in ways that go beyond the provision of facts. A few of the studies reviewed here included elements of participatory approaches (context highlighted in italics in Table 3)—all of which showed hopeful signs of leading to positive behavioural responses. By engaging communities as a whole into a change process, such approaches may be more likely to eventually change norms and the broader cultural and policy context within which individual behaviours and social practices take place. Many desired forms of pro-environmental behaviour change can only take place once suitable normative, infrastructure and policy context are in place. We discuss further below how communication that seeks to engage the public’s emotions, activates social norms, tap into social identity, and connects people to collective action provide interesting opportunities for future research.

Recommendations

Based on our review, we developed recommendations for communicating air pollution to engage the public and change behaviours (Fig. 2). We also urge such a framework to be evaluated. Eleven recommendations relate to the Message Communicated and two recommendations each relate to: Channel of Communication, Receiver and Source of Communication. Our recommendations target individuals’ automatic and reflective motivation. However, at the centre of our recommendations lies the need to address barriers in the social and physical environment, as supported by the equal importance of Opportunity and Capability within the COM-B model of behaviour (Michie et al. 2011) and theories such as the socio-ecological model (Stokols 1992) and social practice theory (Welch 2017). Some recommendations are derived from a critical interpretation of gaps in the academic literature; we refer to those as ‘promising gaps’ (noted with a * in Fig. 2) that require further research. We also highlight the collaborators that offer important insights (outer circular text). While we recognize that this long list of recommendations are based on relatively weak evidence from the academic literature we reviewed, in line with behavioural theories including social practice, planned behaviour, social cognitive theory, or socio-ecological models (Stokols 1992; Welch 2017; Ajzen 1991; Bandura 1999), we believe it is the combination of approaches that tackle behaviour from self-efficacy to social norms that can be most effective in bringing about needed societal changes. Such comprehensive frameworks have not yet been evaluated in the context of air pollution. We refer the reader to White and Habib (2018) for a definition of terms and overview of behavioural theories in the context of sustainable behaviour promotion. Next, we discuss in detail recommendations (highlighted in italics in text) outlined in Fig. 2.

Recommendations for air pollution communication to engage the public and encourage behaviour change. Recommendations align with the SMCR framework and also relate to the three components in the COM-B model of behaviour change. *refers to promising gaps requiring further research identified in the literature review. The outer ring relates to recommended collaborating stakeholders

Target barriers in the social and physical environment

Whilst this review aims to draw out best practice air pollution communication, the effectiveness of communication as a sole behaviour change intervention is limited. Barriers to behaviour change exist in the physical and social environment that information alone is unable to overcome. Cycling or taking public transport choices for example may depend on travel distances, accessibility of affordable public transport or cycle paths (Blanken et al. 2001), availability of safe and well-lit routes (Cannibal and Lemon 2000; Laferriere and Crighton 2017; Noonan 2014; Tribby et al. 2013; Vardoulakis et al. 2018), schedule inflexibility (Eghbalnia et al. 2013; Henry and Gordon 2003; Johnson 2003; Lissåker et al. 2016; Tribby et al. 2013), family commitments (Carducci et al. 2017), or lack of time to consider and change behaviour (Carducci et al. 2017; Radisic and Newbold 2016; Vardoulakis et al. 2018). Even the most ‘perfectly’ worded messages delivered at the right time will not change a person’s behaviour if they do not have the physical or social opportunity to engage. Communication needs to take place in an environment in which the social, physical and environmental barriers to behaviour change are also being addressed (Stokols 1992). Information can nevertheless inform people and encourage certain action, including action that can lead to changing their capability (e.g. cycling classes) or action that can lead to changing opportunities for behaviour change (e.g. policy support for developing cycling infrastructure). A social practice perspective may offer a way forward in this regard (Welch 2017; Shove 2010).

Source of the message

Establishing trust and credibility as a source of information is important for communication to be accepted by the public, as has also been shown in relation to other hazards (Walker et al. 1998). The public may disengage with information considered partisan, compromised or commercial. Furthermore, it is unlikely that people will be successfully engaged with communication that suggests that the responsibility for improving air pollution, and for reducing public exposure to it, lies at the individual level. Research finds that the public feels individual-level action on air pollution and the environment is futile and that responsibility for improving air pollution primarily lies at the local and national level (European Commission 2019; Jacobi 1994; Oltra and Sala 2014). We, therefore, recommend communication recognises these expectations and frames action on air pollution as a collective responsibility by demonstrating collective action and leadership, as supported by social practice and social identity theories, for example (White and Habib 2018; Shove 2010).

Message content

Messages that connect people to and emphasise collective action can strengthen engagement through reinforcing perceptions of collective responsibility. Communication that suggests a range of possible actions increases the chances that an individual is able to respond. For example, whilst it may be difficult for an individual to avoid travelling in rush hour, taking a less polluted route might be a feasible option; while taking children to school on bicycles may feel too risky, joining a community group that lobbies for cycling infrastructure may be less daunting. Currently, air pollution communication tends to focus on only one behaviour at a time (primarily avoidance or protective behaviours) minimizing opportunities for behaviour change and engagement. In the context of air pollution, low self-efficacy, a person’s belief that their own action(s) can have a desired impact on an outcome (Bandura 1999), is a recognised barrier to behaviour change (Bickerstaff and Walker 2001; D’Antoni et al. 2017). Furthermore, raising concern and anxiety about pollution without offering solutions can lead to disengagement (Abrahamse et al. 2005; Bickerstaff 2004; Bickerstaff and Walker 2001). Lack of actionable information may explain partly the failure of some engagement efforts (e.g. Haddad and de Nazelle 2018). Therefore, offering a range of solutions increases self-efficacy, prevents disengagement and may enable behaviour change.

As part of the range of actions, communication could place greater emphasis on encouraging supportive behaviours such as writing to local MPs, engaging in discussion and actions with the local community and joining or contributing to pressure groups. We found that supportive behaviours are far less prominent compared to avoidance and contributing behaviours, although they are shown to be an effective target behaviour (Hubbell et al. 2018; Mason et al. 2017). This is a missed opportunity for two reasons. First, when local infrastructure does not provide opportunities for desirable changes in daily routines (e.g. travel habits), supportive behaviours remain an option for most, helping prevent disengagement. Second, supportive behaviours can create enabling environments for policy change. Policymakers need public support to take action and push through potentially controversial schemes such as parking and driving restrictions in cities (Riley and de Nazelle 2018). Communication that encourages supportive action may increase engagement and simultaneously enable action from politicians—eventually leading to removal of physical and social barriers that may hinder other beneficial actions.

Air pollution communication campaigns reviewed focused on health benefits from a reduction in pollution, and none communicated the co-benefits of action on air pollution. For example, walking and cycling instead of driving can also improve public health through increasing physical activity, generate personal economic savings from avoided transportation costs, reduce congestion, improve social cohesion and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (de Nazelle et al. 2011). As well as providing a stronger basis for individual-level action and appealing to individuals’ different interests and behavioural drivers, these co-benefits strengthen the case for action for policymakers, compared with emphasizing air pollution reductions alone (Riley and de Nazelle 2018). We note that, in reverse, much of current air quality communication efforts are in fact meant to reduce outdoor activity, including cycling and park attendance. A recent review of the broader literature finds that air pollution alerts reduce physical activity behaviour (An et al. 2019). Such recommendation may be appropriate to protect the population most at risk. However, for most people, the benefits of physical activity by far outweigh risks of increased air pollution inhalation (Mueller et al. 2015; Andersen et al. 2015; Tainio et al. 2021). Recommendation to limit outdoor activities and resulting discouragement of physical activity could in fact be detrimental to the general population (Giallouros et al. 2020).

Information that is relatable, understandable and local is likely to be more engaging than general information on air pollution (Bickerstaff 2004; Bickerstaff and Walker 2003; Christmas et al. 2015; Howel et al. 2003; Kilbane-Dawe et al. 2013). A randomised control trial published after our literature search found that messages targeting specificity resulted in a higher intention to change behaviour than existing Air Quality Index messages (D’Antoni et al. 2019). Information that is too broad or too general (for example information provided at a regional or national level) is unlikely to engage people. Public perceptions of pollution are grounded in local places, local hotspots and local sources. The way the public perceives air pollution is often characterised by the ‘halo effect’ whereby they attribute pollution levels in other neighbourhoods as worse than in their own. This may be explained by the concept of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957): when confronted with uncomfortable information (e.g. living in an high pollution area), people tend to dismiss or rationalise it away rather than live with the discomfort. Communication that draws on local places can emphasise the immediacy and ‘closeness’ of pollution and thus counteract this effect, as supported by construal theory (White et al. 2011).

Similarly, people may recognise that air pollution affects the health of others, but frequently reject suggestions that their own health is affected (Bickerstaff and Walker 2003). Positive framing that focuses on the gains and benefits from action rather than the losses from inaction may reassure and empower people that there are feasible actions to mitigate the effects of pollution. Research on integrating positive messaging to issues around conservation and recycling supports these findings (Davis 1995; Kidd et al. 2019; Kusmanoff et al. 2016)).

Current air pollution communication relies on data, indices and numbers with little focus on connecting with people’s emotions or placing humans at the centre of communication. The drive for more accurate or precise data is unlikely to engage people at scale unless this information is made relevant to people and their everyday lives, engaging with them emotionally in a way that can trigger individuals’ automatic motivations. Some suggest putting air pollution information in the context of other known health risks such as passive smoking or premature death (Kelly and Fussell 2015), or using historical data to give context (Hubbell et al. 2018). Whilst this may provide context to the numbers, it implicitly assumes that more information can lead to greater engagement and are open to criticisms of the ‘information-deficit model’ (Suldovsky 2016). Our behaviours, however, can be driven by emotion as well as reason, what Kahneman (2011) refers to as “fast thinking”. Engagement opportunities lie in moving beyond the communication of data to connect with people’s emotions and senses through human-centred communication, personification, storytelling and metaphor (Cheng et al. 2008; Dahlstrom 2014; Feinberg and Willer 2011; Green et al. 2018). Research on conservation communication highlights the effectiveness of using charismatic flagship species, such as pandas and turtles, that tap into our biological instinct to protect and to care for those who are more vulnerable (Kusmanoff et al. 2016). Others find communication that taps into emotions of disgust or affiliation are effective for behaviour change in different health settings (Curtis et al. 2011; Winch and Thomas 2016). In terms of air pollution, communicating in ways that tap into peoples’ sense of affiliation or belonging, protection, nurture, empathy or sense of pride and purpose are interesting and promising avenues for further research. Presenting the facts alone is less likely to result in long-term changes in feelings and behaviours (Opermanis et al. 2015).

Channel of communication

The channel of communication should be appropriate to deliver the message outlined above. We find a disconnect between channels of communication used and what the evidence points to as more effective message content. Whilst most communication relies on national newspapers, television and websites, these mass channels are unlikely to deliver local, positive, personal and targeted messages. New forms of communication such as smartphone application, mobile sensors and wearable devices offer opportunities to communicate with individuals in a tailored and personal way (e.g. providing personalised exposure information and tailored health recommendations), at scale and at the right time (Dennison et al. 2013). Smartphone applications are increasingly employed to encourage both environmental and health behaviours. Nonetheless, they are not effective in themselves, and will engage only in as much as they integrate effective messages (e.g. local, actionable, targeted) and community-oriented actions, which currently are mostly lacking from such efforts. A recent study exploring how the public responded to information from an air pollution sensor presented to them through smartphones with little targeted messaging other than exposure information, and low trust in the source, found no impact on intention to change behaviour (Haddad and de Nazelle 2018).

New technologies such as smartphones and mobile sensors offer opportunities to increase engagement in air pollution also as part of citizen science and community initiatives. Such projects, if developed with appropriate consideration to engage community members and remove access barriers, have the potential to generate a sense of collective responsibility and increasing self-efficacy and empowerment. However, research also highlights potential risks of community sensing initiatives (Hubbell et al. 2018) that may transfer responsibility for exposure reduction to individuals (as a way out for governments to avoid taking responsibility). Other risks include misinterpretation of the data on the part of communities or individuals, which may result in higher levels of anxiety or less physical activity as people seek to protect themselves by avoiding going outside (Hubbell et al. 2018). Such approaches must, therefore, be considerate of the broader context of behaviour change to be engaging through community participatory processes.

Most studies investigate communication during high pollution episodes and few consider continuous communication and sustained educational approaches, which again, can be enabled by smartphone technologies, to promote sustainable behaviour change. Relying on air pollution alerts alone may hamper effective action as they depend on individuals’ ability to see and respond at short notice; risk subjecting the public to alarmist framing which may lead to disengagement; risk communicating that pollution is only a problem during peak times and that behaviour change is unwarranted at other times.

Personalised channels of communication such as smartphone apps can also draw on automatic responses through connection with emotions. They can use personification and metaphors, such as through avatars, and can activate social norms and identities by creating opportunities for comparisons with others. An emerging research area is the use of gamification to engage people and change behaviours. A recent systematic review finds that gamification can have a positive impact for health and wellbeing particularly when used to target behavioural outcomes such as physical activity (Johnson et al. 2016). Others similarly find gamification effective for pro-environmental behaviour promotion such as energy saving (Morganti et al. 2017). More research is needed on mechanisms through which gamification can be effective and on impacts on long-term behaviour change (Edwards et al. 2016). While not previously evaluated using smartphones, air pollution gamification did appear in two studies reviewed: one showed a competition across teams and cities in Europe was successful in obtaining citizen-based air quality monitoring, and in raising awareness about air pollution ( et al. 2015); another could not robustly attribute reductions in ozone to a summer-period car-reduction challenge in a US city (Teague et al. 2015).

Receiver of information

Tailoring air pollution information to the individual can encourage engagement and may overcome the halo effect. We recommend personalizing the framing of pollution depending on individuals’ preferences and drivers, for example emphasising health, social and environmental impacts, or financial cost. Studies have explored how various framing of environmental issues can affect public engagement (Davis 1995; Noble et al. 2014). Research also highlights how social norms and tacitly agreed regularities observed amongst groups of individuals influence behaviour (Charles and Charles 2012), such as in relation to energy and health behaviours (Allcott 2011; Cialdini and Trost 1998; Goldstein et al. 2008). Individuals identify with different groups depending on their beliefs and ideas, which in return sets benchmarks of behavioural expectations. Understanding how these different social identities can be triggered and leveraged to encourage engagement and behaviour change is a promising research area—possibly enabled by smartphone-based approaches.

Collaborations

To overcome the tradition of treating the public as recipients of information, engaging with individuals and community groups to understand their needs and expectations is recommended (Hubbell et al. 2018; Kelly et al. 2012; Oltra and Sala 2015). Community-based, participatory approaches that include the public in message content and design can empower local people, increase ownership and agency, and result in higher levels of engagement if risks are managed (Hsu et al. 2017; Hubbell et al. 2018; Mason et al. 2017; Oltra and Sala 2015; et al. 2015). Furthermore, approaches that tell stories, connect people with their emotions, and place them at the heart of communication on the science and data can provide useful information that people will trust: this approach necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration between scientists, designers, businesses, artists, and communities (Curtis 2009; Curtis et al. 2012).

Conclusion

Current approaches to communicating air pollution continue to depend on top-down, keep it simple approaches, and are missing opportunities for engaging a greater number of people in a more effective way. We identify best practice air pollution communication and highlight promising gaps in need of further research. Providing information is an important and necessary step to raise awareness and affect motivations. Current information-based approaches can be complemented by approaches that seek to activate social norms, connect with peoples’ emotions and trigger responses based on feelings of collective responsibility. Care should be taken to prevent unintended consequences such as reducing physical activity as seen with air pollution alerts, or shifting responsibility away from government action and onto individuals. Practitioners and researchers would do well to think creatively about air pollution communication to move beyond the current reliance on the one-way provision of data.

References

Abrahamse W, Steg L, Vlek C, Rothengatter T (2005) A review of intervention studies aimed at household energy conservation. J Environ Psychol 25:273–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.08.002

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Allcott H (2011) Social norms and energy conservation. J Public Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.03.003

An R, Shen J, Ying B, Tainio M, Andersen ZJ, de Nazelle A (2019) Impact of ambient air pollution on physical activity and sedentary behavior in China: a systematic review. Environ Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.108545

Andersen ZJ, de Nazelle A, Mendez MA, Garcia-Aymerich J, Hertel O, Tjønneland A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ (2015) A study of the combined effects of physical activity and air pollution on mortality in elderly urban residents: The Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408698

Bandura A (1999) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Asian J Soc Psychol 2:21–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00024

Beaumont R, Hamilton RS, Machin N, Perks J, Williams ID (1999) Social awareness of air quality information. Sci Total Environ 235:319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00215-6

Becker MH (1974) The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Educ Monogr 2:409–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200407

Berlo D (1960) The process of communication. Rinehart & Winston, New York

Bickerstaff K (2004) Risk perception research: socio-cultural perspectives on the public experience of air pollution. Environ Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2003.12.001

Bickerstaff K, Walker G (2001) Public understandings of air pollution: the “localisation” of environmental risk. Glob Environ Chang 11:133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00063-7

Bickerstaff K, Walker G (2003) The place(s) of matter: matter out of place—public understandings of air pollution. Prog Hum Geogr 27:45–68. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph412oa

Blanken PD, Dillon J, Wismann G (2001) The impact of an air quality advisory program on voluntary mobile source air pollution reduction. Atmos Environ 35:2417–2421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00523-9

Borbet TC, Gladson LA, Cromar KR (2018) Assessing air quality index awareness and use in Mexico City. BMC Public Health 18:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5418-5

Brown P, Cameron L, Cisneros R, Cox R, Gaab E, Gonzalez M, Ramondt S, Song A (2016) Latino and non-latino perceptions of the air quality in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13121242

Cannibal G, Lemon M (2000) The strategic gap in air-quality management. J Environ Manage 60:289–300. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2000.0385

Carducci A, Donzelli G, Cioni L, Palomba G, Verani M, Mascagni G, Anastasi G, Pardini L, Ceretti E, Grassi T, Carraro E, Bonetta S, Villarini M, Gelatti U (2017) Air pollution: a study of citizen’s attitudes and behaviors using different information sources. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health 14:1–9. https://doi.org/10.2427/12389

Charles A, Charles A (2012) Identity, norms, and ideals. In: Exchange entitlement mapping https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137014719_3

Cheng D, Claessens M, Gascoigne T, Metcalfe J, Schiele B, Shi S (2008) Communicating science in social contexts: new models, new practices. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8598-7

Christmas S, Wallace M, Clement L, Kilbane-dawe I, Bradburn H (2015) Project AQ1010 research report communicating with the public about air pollution findings from qualitative research with the general public on the topic of air pollution

Cialdini RB, Trost MR (1998) Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance. In: The handbook of social psychology

Cole DC, Pengelly LD, Eyles J, Stieb DM, Hustler R (1999) Consulting the community for environmental health indicator development: the case of air quality. Health Promot Int 14:145–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/14.2.145

Commission E (2019) Attitudes of Europeans towards air. Quality. https://doi.org/10.2834/00469

Curtis DJ (2009) Creating inspiration: the role of the arts in creating empathy for ecological restoration. Ecol Manage Restor. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-8903.2009.00487.x

Curtis V, Barra MD, Aunger R (2011) Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 366:389–401. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0117

Curtis DJ, Reid N, Ballard G (2012) Communicating ecology through art: what scientists think. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04670-170203

D’Antoni D, Smith L, Auyeung V, Weinman J (2017) Psychosocial and demographic predictors of adherence and non-adherence to health advice accompanying air quality warning systems: a systematic review. Environ Heal A Glob Access Sci Source 16:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0307-4

D’Antoni D, Auyeung V, Walton H, Fuller GW, Grieve A, Weinman J (2019) The effect of evidence and theory-based health advice accompanying smartphone air quality alerts on adherence to preventative recommendations during poor air quality days: a randomised controlled trial. Environ Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.002

Daher N, Yasmin F, Wang MR, Moradi E, Rouhani O (2018) Perceptions, preferences, and behavior regarding energy and environmental costs: the case of Montreal transport users. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020514

Dahlstrom MF (2014) Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Davis JJ (1995) The effects of message framing on response to environmental communications. Journal Mass Commun Q 72(2):285–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909507200203

De Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJMJ, Antó JMJM, Brauer M, Briggs D, Braun-Fahrlander C, Cavill N, Cooper ARAR, Desqueyroux H, Fruin S, Hoek G, Panis LILI, Janssen N, Jerrett M, Joffe M, Andersen ZJZJ, van Kempen E, Kingham S, Kubesch N, Leyden KMKM, Marshall JDJD, Matamala J, Mellios G, Mendez M, Nassif H, Ogilvie D, Peiró R, Pérez K, Rabl A, Ragettli M, Rodríguez D, Rojas D, Ruiz P, Sallis JFJF, Terwoert J, Toussaint JFJ-F, Tuomisto J, Zuurbier M, Lebret E (2011) Improving health through policies that promote active travel: a review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ Int 37:766–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.003

Delhomme P, Chappé J, Grenier K, Pinto M, Martha C (2010) Reducing air-pollution: a new argument for getting drivers to abide by the speed limit? Accid Anal Prev 42:327–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2009.08.013

Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, Yardley L (2013) Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2583

De Dios Ortuzar J, Hensher D, Jara-Diaz S (1998) Travel behavior research: updating the state of play. Travel behavior research: updating the state of play. Pergamon Press. ISBN-10:008043360X

Edwards EA, Lumsden J, Rivas C, Steed L, Edwards LA, Thiyagarajan A, Sohanpal R, Caton H, Griffiths CJ, Munafò MR, Taylor S, Walton RT (2016) Gamification for health promotion: systematic review of behaviour change techniques in smartphone apps. BMJ Open 6:e012447. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012447

Eghbalnia C, Sharkey K, Garland-Porter D, Alam M, Crumpton M, Jones C, Ryan PH (2013) A community-based participatory research partnership to reduce vehicle idling near public schools. J Environ Health 75(9):14–19

Feinberg M, Willer R (2011) Apocalypse soon? Dire messages reduce belief in global warming by contradicting just-world beliefs. Psychol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610391911

Festinger L (1957) An introduction to the theory of dissonance. In: A theory of cognitive dissonance. https://doi.org/10.1037/10318-001

Finney MM (2014) Information and the demand for clean air. Contemp Econ Policy 32:719–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12041

Giallouros G, Kouis P, Papatheodorou SI, Woodcock J, Tainio M (2020) The long-term impact of restricting cycling and walking during high air pollution days on all-cause mortality: Health impact Assessment study. Environ Int 140:105679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105679

Giardullo P, Sergi V, Carton W, Kenis A, Kesteloot C, Kazepov Y, Kobus D, Maione M, Skotak K, Fuzzi S, Pollini F (2016) Air quality from a social perspective in four European metropolitan areas: research hypothesis and evidence from the SEFIRA project. Environ Sci Policy 65:58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.05.002

Goldstein NJ, Cialdini RB, Griskevicius V (2008) A room with a viewpoint: using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J Consum Res. https://doi.org/10.1086/586910

Green SJ, Grorud-Colvert K, Mannix H (2018) Uniting science and stories: perspectives on the value of storytelling for communicating science. Facets. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2016-0079

Haddad H, de Nazelle A (2018) The role of personal air pollution sensors and smartphone technology in changing travel behaviour. J Transp Heal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2018.08.001

Henry GT, Gordon CS (2003) Driving less for better air: impacts of a public information campaign. J Policy Anal Manage. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.10095

Howel D, Moffatt S, Bush J, Dunn CE, Prince H (2003) Public views on the links between air pollution and health in Northeast England. Environ Res 91:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-9351(02)00037-3

Hsu Y-C, Dille P, Cross J, Dias B, Sargent R, Nourbakhsh I (2017) Community-empowered air quality monitoring system. In: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp 1607–1619. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025853

Hubbell BJ, Kaufman A, Rivers L, Schulte K, Hagler G, Clougherty J, Cascio W, Costa D (2018) Understanding social and behavioral drivers and impacts of air quality sensor use. Sci Total Environ 621:886–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.275

Jacobi PR (1994) Households and environment in the city of São Paulo; problems, perceptions and solutions. Environ Urban. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789400600206

Jasemzadeh M, Khafaie MA, Jaafarzadeh N, Araban M (2018) Effectiveness of a theory-based mobile phone text message intervention for improving protective behaviors of pregnant women against air pollution: a randomized controlled trial. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:6648–6655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-1034-7

Johansson C, Lövenheim B, Schantz P, Wahlgren L, Almström P, Markstedt A, Strömgren M, Forsberg B, Sommar JN (2017) Impacts on air pollution and health by changing commuting from car to bicycle. Sci Total Environ 584–585:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.145

Johnson BB (2003) Communicating air quality information: experimental evaluation of alternative formats. Risk Anal 23:91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1539-6924.00292

Johnson BB (2012) Experience with urban air pollution in Paterson, New Jersey and implications for air pollution communication. Risk Anal 32:39–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01669.x

Johnson D, Deterding S, Kuhn KA, Staneva A, Stoyanov S, Hides L (2016) Gamification for health and wellbeing: a systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv 6:89–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2016.10.002

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking fast, thinking slow, Interpretation. Tavistock, London

Kelly FJ, Fussell JC (2015) Air pollution and public health: emerging hazards and improved understanding of risk. Environ Geochem Health 37:631–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-015-9720-1

Kelly FJ, Fuller GW, Walton HA, Fussell JC (2012) Monitoring air pollution: use of early warning systems for public health. Respirology 17:7–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02065.x

Kidd LR, Garrard GE, Bekessy SA, Mills M, Camilleri AR, Fidler F, Fielding KS, Gordon A, Gregg EA, Kusmanoff AM, Louis W, Moon K, Robinson JA, Selinske MJ, Shanahan D, Adams VM (2019) Messaging matters: a systematic review of the conservation messaging literature. Biol Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.05.020

Kilbane-Dawe I, Clement L, Bradburn H, Christmas S (2013) Parliament Hill Research Defra Project AQ1010 developing communication methods for localised air quality and health impact information. Final report, pp 1–72

Kusmanoff AM, Hardy MJ, Fidler F, Maffey G, Raymond C, Reed MS, Fitzsimons JA, Bekessy SA (2016) Framing the private land conservation conversation: strategic framing of the benefits of conservation participation could increase landholder engagement. Environ Sci Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.03.016

Laferriere K, Crighton EJ (2017) “During pregnancy would have been a good time to get that information”: mothers’ concerns and information needs regarding environmental health risks to their children1. Int J Health Promot Educ 55:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2016.1242376

Lissåker CTK, Talbott EO, Kan H, Xu X (2016) Status and determinants of individual actions to reduce health impacts of air pollution in US adults. Arch Environ Occup Heal 71:43–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2014.988673

Mason LR, Hathaway JM, Ellis KN, Harrison T (2017) Public interest in microclimate data in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. Sustain 9:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010023

Meleady R, Abrams D, Van de Vyver J, Hopthrow T, Mahmood L, Player A, Lamont R, Leite AC (2017) Surveillance or self-surveillance? Behavioral cues can increase the rate of drivers’ pro-environmental behavior at a long wait stop. Environ Behav 49:1156–1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517691324

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Mir HM, Behrang K, Isaai MT, Nejat P (2016) The impact of outcome framing and psychological distance of air pollution consequences on transportation mode choice. Transp Res D Transp Environ 46:328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2016.04.012

Mirabelli MC, Boehmer TK, Damon SA, Sircar KD, Wall HK, Yip FY, Zahran HS, Garbe PL (2018) Air quality awareness among U.S. adults with respiratory and heart disease. Am J Prev Med 54:679–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.037

Morganti L, Pallavicini F, Cadel E, Candelieri A, Archetti F, Mantovani F (2017) Gaming for Earth: serious games and gamification to engage consumers in pro-environmental behaviours for energy efficiency. Energy Res Soc Sci 29:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.001

Mueller N, Rojas-Rueda D, Cole-Hunter T, de Nazelle A, Dons E, Gerike R, Nieuwenhuijsen M (2015) Health impact assessment of active transportation: a systematic review. Prev Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.010

Mullins J, Bharadwaj P (2015) Effects of short-term measures to curb air pollution: evidence From Santiago, Chile. Am J Agric Econ 97:1107–1134. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aau081

Neidell M (2010) Air quality warnings and outdoor activities: evidence from Southern California using a regression discontinuity design. J Epidemiol Commun Health 64:921–926. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.081489

Noble G, Pomering A, Johnson LW (2014) Gender and message appeal: their influence in a pro-environmental social advertising context. J Soc Mark. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-12-2012-0049

Noonan DS (2014) Smoggy with a chance of altruism: the effects of ozone alerts on outdoor recreation and driving in Atlanta. Policy Stud J 42:122–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12045

Oltra C, Sala R (2014) A review of the social research on public perception and engagement practices in urban air pollution.

Oltra C, Sala R (2015) Communicating the risks of urban air pollution to the public: a study of urban air pollution information services. Rev Int Contam Ambient 31:361–375

Oltra C, Sala R, Boso À, Asensio SL (2017) Public engagement on urban air pollution: an exploratory study of two interventions. Environ Monit Assess. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-6011-6

Opermanis O, Kalnins SN, Aunins A (2015) Merging science and arts to communicate nature conservation. J Nat Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2015.09.005

Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Kerry KE (2008) The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Health behaviour and health education. Theory, research, and practice. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyh005

Radisic S, Newbold B (2016) Factors influencing health care and service providers’ and their respective “at risk” populations’ adoption of the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI): a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 16:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1355-0

Riley R, de Nazelle A (2018) Barriers and enablers of integrating health evidence into transport and urban planning and decision making. In: Integrating human health into urban and transport planning: a framework, pp. 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74983-9_31

Rojas-Rueda D, De Nazelle A, Tainio M, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ (2011) The health risks and benefits of cycling in urban environments compared with car use: health impact assessment study. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4521

Rojas-Rueda D, de Nazelle A, Teixidó O, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ (2012) Replacing car trips by increasing bike and public transport in the greater Barcelona metropolitan area: a health impact assessment study. Environ Int 49:100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2012.08.009

Rosenstock IM (1974) The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr 2:354–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/014572178501100108

Royal College of Physicians (2016) Every breath we take: the lifelong impact of air pollution. Rep a Work Party. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-7058/29/9/40

Saberian S, Heyes A, Rivers N (2017) Alerts work! Air quality warnings and cycling. Resour Energy Econ 49:165–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2017.05.004

Semenza JC, Wilson DJ, Parra J, Bontempo BD, Hart M, Sailor DJ, George LA (2008) Public perception and behavior change in relationship to hot weather and air pollution. Environ Res 107:401–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2008.03.005

Shapiro R, Hassett K, Arnold F (2002) Conserving energy and preserving the environment: the role of public transportation. Rep Commissioned American Pub Transp Ass Transp. https://sonecon.com/docs/studies/enenv_0702.pdf

Shove E (2010) Beyond the ABC: climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ Plan A. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282

Sîrbu A, Becker M, Caminiti S, De Baets B, Elen B, Francis L, Gravino P, Hotho A, Ingarra S, Loreto V, Molino A, Mueller J, Peters J, Ricchiuti F, Saracino F, Servedio VDP, Stumme G, Theunis J, Tria F, Van Den Bossche J (2015) Participatory patterns in an international air quality monitoring initiative. PLoS ONE 10:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136763

Skov T, Cordtz T, Jensen LK, Saugman P, Schmidt K, Theilade P (1991) Modifications of health behaviour in response to air pollution notifications in Copenhagen. Soc Sci Med 33:621–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90220-7

Stokols D (1992) Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol 47(1):6–22

Suldovsky B (2016) In science communication, why does the idea of the public deficit always return? Exploring key influences. Public Underst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516629750

Tainio M, Jovanovic Andersen Z, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Hu L, de Nazelle A, An R, de Sá TH (2021) Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence. Environ Int. v147:105954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105954

Teague SW, Zick DC, Smith RK (2015) Soft transport policies and ground-level ozone: an evaluation of the “clear the air challenge” in Salt Lake City. Policy Stud J 43:399–415

The Health Effects Institute (2017) State of global air. Available from www.stateofglobalair.org. Accessed 14 August 2017

Tribby CP, Miller HJ, Song Y, Smith KR (2013) Do air quality alerts reduce traffic? An analysis of traffic data from the Salt Lake City metropolitan area, Utah, USA. Transp Policy 30:173–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2013.09.012

Vardoulakis S, Kettle R, Cosford P, Lincoln P, Holgate S, Grigg J, Kelly F, Pencheon D (2018) Local action on outdoor air pollution to improve public health. Int J Public Health 63:557–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1104-8

Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC (2010) Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 376:1261–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4

Walker G, Simmons P, Irwin A, Wynne B (1998) Public Perception of Risks Associated with Major Accident Hazards. HSE Books. http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/crr_pdf/1998/crr98194.pdf

Ward AS, Beatty TKM (2016) Who responds to air quality alerts? Environ Resour Econ 65:487–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-015-9915-z

Weiss JA, Tschirhart M (2006) Public information campaigns as policy instruments. J Policy Anal Manage. https://doi.org/10.2307/3325092

Welch D (2017) Behaviour change and theories of practice: contributions, limitations and developments. Soc Bus. https://doi.org/10.1362/204440817x15108539431488

Welch E, Gu X, Kramer L (2005) The effects of ozone action day public advisories on train ridership in Chicago. Transp Res D Transp Environ 10:445–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2005.06.002

Wen XJ, Balluz L, Mokdad A (2009) Association between media alerts of air quality index and change of outdoor activity among adult asthma in six states, BRFSS, 2005. J Community Health 34:40–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9126-4

White K, Habib R (2018) SHIFT—a review and framework for encouraging environmentally sustainable consumer behaviour. Retrieved from www.sitra.fi

White K, Macdonnell R, Dahl DW (2011) It’s the mind-set that matters: the role of construal level and message framing in influencing consumer efficacy and conservation behaviors. J Mark Res 48(3):472–485. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.3.472

Whitmarsh L, O’Neill S, Lorenzoni I (2012) Engaging the public with climate change: Behaviour change and communication. Taylor & Francis, UK

Winch PJ, Thomas ED (2016) Harnessing the power of emotional drivers to promote. Lancet Glob Heal 4:e881–e882. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30310-2

Woodcock J, Edwards P, Tonne C, Armstrong BG, Ashiru O, Banister D, Beevers S, Chalabi Z, Chowdhury Z, Cohen A, Franco OH, Haines A, Hickman R, Lindsay G, Mittal I, Mohan D, Tiwari G, Woodward A, Roberts I (2009) Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport. Lancet 374:1930–1943

World Health Organization (2013) Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution—REVIHAAP Project. World Heal. Organ. Reg. Off. Eur.

World Health Organization (2018) Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health [WWW Document]. URL https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

World Health Organization (2020) Personal interventions and risk communication on air pollution personal interventions and risk communication on air pollution. World Health Organization (WHO) Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

Acknowledgements

Rosie Riley is a PhD student funded by the UK Economic & Social Research Council through the London Interdisciplinary Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership (LISS DTP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handled by Lotten Westberg, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Urban and Rural Development, Sweden.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions