Abstract

Democratic institutions that coordinate diffuse interests might be beneficial for climate protection. Because the implementation of democratic institutions varies among democracies as well as among autocracies, this study examines whether institutional aspects of different models of democracy affect CO2 emissions in democracies and autocracies. Similar studies have assumed uniform effects of democratic aspects in regimes of both types. The extent of the dependence of autocratic leaders on the support of the ruling party, the military, and/or a hereditary council might make them less responsive to incentives generated by democratic institutions to reduce CO2 emissions. This article, therefore, examines data on CO2 emissions from 1990 to 2020 in 66 democracies and 69 autocracies separately and analyses whether nondemocratic institutions limit the effects of democratic institutions. As democratic institutions might affect climate outcomes only in the long term, we examine cross-national variation in the long-term development of CO2 emissions and short-term changes in CO2 emissions within countries. In democracies, civil society participation and social equality contribute to a decrease in the long-term development of CO2 emissions. In autocracies, local and regional democracy contributes to lower CO2 emissions in the long term, and social equality decreases annual changes in CO2 emissions. Military influence limits these effects. In contrast, the dependence of the executive on a ruling party strengthens the negative effect of social equality on annual changes in CO2 emissions.

Zusammenfassung

Demokratische Institutionen, die unterschiedliche Interessen koordinieren, könnten für den Klimaschutz von Vorteil sein. Da die Implementierung demokratischer Institutionen sowohl zwischen Demokratien als auch zwischen Autokratien variiert, wird in dieser Studie untersucht, ob institutionelle Aspekte verschiedener Demokratiemodelle die CO2-Emissionen in Demokratien und Autokratien beeinflussen. Ähnliche Studien gehen von einheitlichen Auswirkungen demokratischer Aspekte in beiden Regimetypen aus. Das Ausmaß der Abhängigkeit autokratischer Führer von der Unterstützung durch die Regierungspartei, das Militär und/oder einen Erbschaftsrat könnte dazu führen, dass sie weniger auf Anreize reagieren, die durch demokratische Institutionen zur Reduzierung der CO2-Emissionen geschaffen werden. In diesem Artikel werden daher Daten zu den CO2-Emissionen von 1990 bis 2020 in 66 Demokratien und 69 Autokratien getrennt untersucht und analysiert, ob nichtdemokratische Institutionen die Auswirkungen demokratischer Institutionen begrenzen. Da sich demokratische Institutionen möglicherweise nur langfristig auf das Klima auswirken, untersuchen wir länderübergreifende Unterschiede in der langfristigen Entwicklung der CO2-Emissionen und kurzfristige Veränderungen der CO2-Emissionen innerhalb der Länder. In Demokratien tragen die Beteiligung der Zivilgesellschaft und die soziale Gleichheit zu einem Rückgang der langfristigen Entwicklung der CO2-Emissionen bei. In Autokratien trägt die lokale und regionale Demokratie langfristig zu niedrigeren CO2-Emissionen bei, und soziale Gleichheit verringert die jährlichen Veränderungen der CO2-Emissionen. Der militärische Einfluss begrenzt diese Effekte. Dagegen verstärkt die Abhängigkeit der Exekutive von einer Regierungspartei den negativen Effekt der sozialen Gleichheit auf die jährlichen Veränderungen der CO2-Emissionen.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This article examines whether specific democratic institutions affect CO2 emissions in democracies and autocracies and whether nondemocratic institutions limit their effects in autocracies. Global problems such as climate change renew questions on the consequences of domestic political institutions for policy performance. The findings of quantitative research on the consequences of different regime types or the level of democratic quality for climate outcomes are ambiguous (e.g., Bättig and Bernauer 2009; Wurster 2013; Clulow 2019). Scholars have concluded that regime type as a dichotomous construct cannot explain differences in CO2 emissions (Christoff and Eckersely 2011; Wurster 2013). Climate outcomes vary among both democracies and autocracies over time. There have been two approaches in quantitative research seeking to improve our understanding of the causal mechanism linking democracy to climate outcomes. First, studies have examined whether the effect of democratic quality on climate outcomes is conditional on contextual conditions (e.g., electoral rules, corruption) that either support or undermine climate protection (e.g., Mayer 2017; Povitkina 2018; Clulow 2019).

Second, quantitative research on democratic quality and climate outcomes has mainly applied summary measures of liberal democratic quality. However, in the theoretical debate, scholars refer to multiple conceptualisations of democracy (electoral, liberal, deliberative, participatory, and egalitarian) and emphasise different institutional aspects (electoral accountability, political rights, checks and balances, civil rights, quality of deliberation, direct democracy, civil society participation, local and regional democracy, and social equality) of these conceptualisations as crucial for climate protection. Accordingly, recent research has examined the importance of specific democratic institutions in explaining variation in climate outcomes (Escher and Walter-Rogg 2018; von Stein 2020).

Climate change mitigation is a collective action problem. As climate protection is associated with considerable short-term socioeconomic costs, it requires public awareness and broad societal support to incentivise government action. Thus, we expect that democratic institutions that coordinate diffuse interests might be beneficial for climate protection. Political rights enable citizens to inform themselves about global environmental change and the public to mobilise in support of climate protection. Greater quality of deliberation can foster public support of common interests. Social equality—i.e., equal access to political power independent from class, religion, culture, or socioeconomic resources—can contribute via the broad political representation of social groups to the consideration of diffuse interests in political debates. Finally, greater participation of civil society as well as local and regional democracy might lead to the representation of diffuse interests and, by fostering greater citizen identification with policy measures, to greater public support for climate protection. The theoretical literature also offers divergent predictions regarding the direction of the impact of these democratic institutions on climate outcomes. Political rights, participation in civil society, and local and regional democracy also enable opponents of climate protection to influence public opinion and undermine climate policy (Bernauer and Koubi 2009; Kim and Yoon 2018; von Stein 2020). Social equality might contribute via greater consumption and energy use to CO2 emissions (Cushing et al. 2015). Empirical research has found no clear support for the hypotheses that contested elections or institutional constraints either support or undermine climate protection (Fredriksson and Neumayer 2013; Wurster 2013; von Stein 2020). Böhmelt et al. (2016) and Escher and Walter-Rogg (2018) found that democratic inclusiveness and political rights contribute to the public commitment to climate action but have no impact on CO2 emissions. Following von Stein (2020), the effect of civil liberties on greenhouse gas emissions is dependent on the relative importance of manufacturing in the domestic economy. Empirical research has arrived at mixed results on the impact of inequality on CO2 emissions (Cushing et al. 2015). Finally, Selseng et al. (2022) observed no effect of electoral, liberal, deliberative, participatory, or egalitarian democratic quality on climate outcomes over time.

In accordance with the goals of this special issue, this article aims to contribute to our understanding of the democracy–sustainability nexus. To improve our understanding of the causal mechanisms that link individual democratic institutions to CO2 emissions, this article makes two contributions that go beyond the present literature. First, this article examines the effects of relevant institutional aspects of different models of democracy separately and simultaneously to ascertain their relative importance. In accordance with Selseng et al. (2022), this article considers institutional aspects of multiple conceptualisations of democracy in the analysis of climate outcomes. However, these authors’ summary measures of institutional aspects of several models of democracy might conceal the effects of individual institutions. As explained above, the theoretical debate offers competing hypotheses regarding the effects of individual institutional aspects. To account for the different effects of these institutional variables, we study each institution separately. To consider all democracy understandings that are applied in the literature on the climate consequences of democracy, this study also partly examines the effects of political outcomes on CO2 emissions. In contrast to procedural conceptualisations, the egalitarian understanding of democracy considers with social equality the equal distribution of socioeconomic resources within society.

Second, studies on specific democratic institutions and climate outcomes have neglected the influence of nondemocratic institutions in autocracies. The implementation of democratic institutions varies among democracies as well as among autocracies (Lührmann et al. 2018). Democracies vary little with regard to aspects of electoral democracy (e.g., electoral accountability; see Escher and Walter-Rogg 2020). In contrast, they differ considerably regarding equal access to the political system and local and regional democracy (Lührmann et al. 2018). Autocracies implement electoral accountability and nonelectoral democracy aspects to varying extents (Lührmann et al. 2018). Therefore, it is important to study the climate consequences of specific democratic institutions in democracies and autocracies. Many quantitative studies have examined a pooled sample of democracies and nondemocracies and assumed that democratic aspects had a uniform effect on climate outcomes across both types of regimes. Our argument is that while democratic institutions should affect climate outcomes in regimes of both types, their effect might vary between democracies and autocracies. Several studies have examined differences in CO2 emissions among subtypes of autocracies (e.g., Wurster 2013; Ward et al. 2014). Autocracies of different subtypes—e.g., one-party regimes, military regimes, and monarchies—are distinguished based on the institutions and persons that can remove the chief executive (Cheibub et al. 2010) or keep political authorities in power (Hadenius et al. 2017; Hadenius and Teorell 2007). We argue that the extent of the dependence of the chief executive on hereditary succession, the military, and/or a single party can be regarded as capturing nondemocratic veto points in the political decision-making process. This dependency makes autocratic leaders less responsive to possible incentives generated by democratic institutions to reduce emissions and thereby limits the effects of these institutions in reducing CO2 emissions.

To address this, we first examine the effects of democratic institutions on CO2 emissions separately for democracies and autocracies. Second, this article adds to research on whether the climate consequences of aspects of democracy are conditional on other variables and examines possible moderation effects of the extent of the dependence of the chief executive on hereditary succession, the military, and/or a single party in autocracies. We expect that the degree of party influence under one-party rule should limit the effects of democratic institutions on CO2 emissions to the smallest extent. As political leaders dependent on one-party rule often use elections to legitimise their regimes, they should accept more democratic rights and should be more responsive to democratic incentives than their counterparts who rely on hereditary councils or the military. Case studies suggest that the acceptance of civil society and environmental movements and the influence of these groups on climate policy output and outcomes vary by autocratic regime type, with one-party governments being more open to democratic rights and more responsive to influences from civil society (e.g., Simpson and Smits 2018, 2022). Quantitative research on autocratic regime subtypes and climate outcomes has relied on dichotomous indicators of subtypes of autocracies. We apply indicators that capture the extent of dependence of the chief executive on a ruling party, hereditary succession, or the military, as the importance of the influence of these institutions varies within subtypes of autocracies (Teorell and Lindberg 2019).

To answer our research question, we tested the effects of individual democratic and nondemocratic institutions on changes in CO2 emissions separately for democracies and autocracies by using available data from 1990 to 2020. To consider that climate outcomes might affect democracy (Fuchs et al. in this issue), we examined changes in CO2 emissions, which vary over time and across countries. Previous research indicates that quality of democracy affects between-variation and within-variation differently (e.g., Clulow 2019). Thus, we examined both between-variation and within-variation using cross-sectional regression and time-series cross-sectional regression analysis. Because institutions that support diffuse interests might decrease CO2 emissions only in the long term, we specifically examined cross-national variation in the long-term development of CO2 emissions as well as short-term variation over time in CO2 emissions within countries. Our findings support that social equality, citizen participation, and local and regional democracy affect climate outcomes. Nondemocratic institutions in autocracies moderate these effects. Finally, democratic institutions affect between-variation in the long-term development of CO2 emissions and short-term within-country variation in CO2 emissions differently.

In the section below, we formulate hypotheses for the empirical analysis. The measurement of the dependent and independent variables is then explained, followed by the regression analyses to explore our hypotheses. Finally, we present our conclusions and implications for future research.

2 Hypotheses

This section first argues that among the institutions with possible effects on the outcome of interest, democratic institutions that coordinate diffuse interests might have the greatest potential to contribute to lower CO2 emissions, and their influence on climate outcomes should be studied separately. Second, in autocracies, the degrees of influence of the ruling party, hereditary council, and/or military on the executive must be taken into account, as they should limit the negative effects of democratic institutions on CO2 emissions to varying extents.

2.1 Democratic Institutions and CO2 Emissions

Green political theorists differ regarding the models of democracy that they apply to examine the climate effects of democracy. With regard to electoral democracy, the importance of contested elections and political rights for climate outcomes is analysed. Liberal perspectives emphasise civil rights as well as checks and balances. From the perspective of an egalitarian model of democracy, the relevance of social equality among social groups is stressed. Finally, theorists of deliberative and participatory democracy focus on quality of deliberation, direct democracy, participation of civil society, and democracy at the local and regional levels of the political system.

Climate protection imposes considerable social and economic costs in the short term, so individuals and societies might not be able to coordinate to act on the diffuse interest in engaging in climate protection. Climate change mitigation, therefore, depends on public awareness of global environmental change and support for climate protection. Hamilton (2010) argues that to solve the climate crisis, democracy must be changed so that it considers long-term citizen interests over the short-term interests of political and economic elites. Simpson and Smits (2022) emphasise that in autocracies, climate protection depends on public support and the participation of civil society. Our argument is that among the abovementioned institutional aspects, political rights, quality of deliberation, participation of civil society, local and regional democracy, and social equality in particular might contribute to climate change mitigation in democracies and autocracies. The underlying assumption is that these institutions help coordinate diffuse interests in the political decision-making process. Political rights, i.e., the freedom of expression and association, of the press and of participation in autonomous civil society (Merkel 2004, p. 39), are an important precondition for the coordination of diffuse interests in the political decision-making process. Freedom of media first makes public awareness of global environmental change possible (Winslow 2005). Freedom of expression and association and an independent civil society enable the formation of environmental interest groups (ENGOs) and foster the building of public pressure on climate policy (Bernauer et al. 2013; Fredriksson and Neumayer 2013). According to the theory of deliberative democracy, rational discursive processes make it possible for citizens and political decision-makers to consider long-term, generalised, diffuse interests and the complexity of global environmental change (Dryzek 1992; Eckersley 1995; Arias-Maldonado 2007). Deliberation can contribute to support for climate protection, as it transforms self-interest into generalised attitudes (Dryzek 1987; Miller 1992). Climate policy measures depend on public support and citizen identification with the policies (Leggewie and Welzer 2008). Civil society participation ensures the representation of more policy preferences in the political decision-making process and contributes to identifying, raising awareness of, and solving environmental problems and increasing support for climate policies (Winslow 2005; Carbonell and Allison 2015; Böhmelt et al. 2016). Local and regional democracy offers citizens and interest groups additional possibilities to inform themselves of the impacts of climate change and to support climate protection efforts via participation and deliberation (Eckersley 1995; Larson and Soto 2008; Burnell 2012). Moreover, democracy at subnational levels might improve climate change mitigation, as local conditions can be taken into account (Ward 1996). Social equality might also make it more likely that diffuse interests are considered in the political decision-making process (Böhmelt et al. 2016). Social equality leads to better representation of social groups in the political system (Cushing et al. 2015). Women and the poor are often more vulnerable to the consequences of global environmental change (e.g., Cushing et al. 2015; UNEP 2016). Women also hold more environmentally friendly attitudes and are more aware of environmental risks (e.g., Fredriksson and Wang 2011; McCright and Dunlap 2011).

The theoretical debate offers competing hypotheses regarding the effects of these institutional aspects. Political rights and participation in civil society also enable opponents of climate protection to influence public opinion and undermine climate policy (Bernauer and Koubi 2009; von Stein 2020). Local and regional democracy implies more possibilities for special interest groups to undermine climate policies (Kim and Yoon 2018). However, public support for climate change mitigation also makes it harder for special interest groups that bear costs from climate protection to oppose emission reduction (Böhmelt et al. 2016, p. 1257). Empirical research has arrived at mixed results on the impact of political rights (Escher and Walter-Rogg 2018, von Stein 2020) and inequality on climate outcomes (Cushing et al. 2015). To account for the possible different effects of these institutional variables, we studied each institution separately.

Moreover, institutions that support diffuse interests might decrease CO2 emissions only in the long term. Only then will democratic institutions lead to an informed and critical society and the formation of ENGOs (Fredriksson and Neumayer 2013). It takes time for governments to deal with long-term policy goals, such as climate protection.

We expect no clear impacts of further institutional aspects discussed in the democracy/environment literature in reducing CO2 emissions. Democratically elected governments are expected to provide more environmental public goods to stay in power than autocratic leaders are (Congleton 1992; Bueno De Mesquita et al. 2003; Bernauer and Koubi 2009). However, voters within a nation-state might reject the socioeconomic costs of climate change mitigation (Shearman and Smith 2007; Held and Hervey 2011). Moreover, the effect of contested elections depends on the electoral success of supporters or opponents of climate protection. While public referenda, as contested elections, can make governments more responsive to citizen interests, they might hinder the adoption and implementation of long-term policies to address climate change (Stadelmann-Steffen 2011). While checks and balances ensure that more policy preferences are considered in the political decision-making process (Held and Hervey 2011; Burnell 2012; Wurster 2013), under such systems, a single veto player may block measures to reduce CO2 emissions (e.g., Beeson 2010; Gilley 2012; Von Stein 2020). Empirical research finds no clear effect (Fredriksson and Neumayer 2013; Wurster 2013; Garmann 2014). Civil rights, i.e., equality before the law and individual liberties such as property rights and freedom of movement and religion, might foster self-interest over climate protection (Hardin 1968; Ophuls 1977). Simultaneously, the rule of law, depending on the stringency of climate policies, might support the implementation of climate measures (Winslow 2005). Table 1 presents our hypotheses.

2.2 Nondemocratic Institutions and CO2 Emissions

Case studies indicate that autocratic leaders can be responsive to the influences of substate actors, bureaucrats, and nonstate actors (Ducket and Wang 2017). There should, however, be no uniform effect of democratic institutions on climate outcomes across democracies and autocracies. The reason for this is that nondemocratic institutions might also influence the behaviour of political authorities. In contrast to their democratic counterparts, autocratic leaders are dependent on nondemocratic institutions. Subtypes of autocracies are commonly distinguished based on the institutions and persons that can appoint and dismiss autocratic leaders. The extent of dependence of the chief executive on hereditary succession, the military, and/or a single party can be regarded as capturing nondemocratic veto points at which political authorities might be hindered from acting in accordance with incentives generated by democratic institutions. Autocratic leaders might opt not to be responsive to public pressure to engage in climate protection. Political rights, deliberation, the representation of social groups, the participation of civil society, and local and regional democracy do not necessarily affect policy outcomes in autocracies (Schmitter and Sika 2017). In China, ENGOs and civil society do not have the same possibilities of influencing climate policy as their counterparts in democracies. In the 1970s and 1980s, the military regime in Chile accepted the formation of ENGOs and, in response to environmental awareness, even introduced a National Commission on Ecology. However, the Chilean junta did not prioritise environmental protection and did not implement the goals of the Commission (Carruthers 2001). The influence of nondemocratic institutions, therefore, should limit the effect of democratic aspects on CO2 emissions.

Additionally, the degree of dependence of political leaders on a ruling party, a hereditary council, or the military should drive variation in their responsiveness to the climate protection incentives generated by democratic institutions. We expect that autocracies with a high degree of influence of the ruling party should be most responsive to incentives from democratic institutions and, therefore, should limit the negative effects of democratic institutions on CO2 emissions to a lesser extent than hereditary or military rule (Hnondemocratic).

First, higher levels of political stability and political competition might contribute to the implementation and effectiveness of long-term, sustainable environmental policies (Gandhi and Przeworski 2007; Wurster 2013; Ward et al. 2014). More stable regimes should also be more likely to consider the socioeconomic consequences of climate change for vulnerable social groups (Burnell 2012). Party regimes stay in power longer than military autocracies (Wurster 2013; Ward et al. 2014). Second, as party regimes often use elections to legitimise their rule, they should in general be more likely to accept more democratic rights than autocratic leaders who are dependent on the military or a hereditary council (Stier 2015). Finally, institutional variation among autocracies implies different opportunities for civil society organisations and ENGOs to influence climate policy (Böhmelt 2014). Party regimes with a larger winning coalition and a higher degree of competition (Wurster 2013) should be more likely to accept civil society and ENGOs than military regimes and monarchies and should offer more opportunities for them to influence government policy. In monarchies, while the formation of civil society and ENGOs is often accepted, their influence is restricted (Böhmelt 2014). Nonstate actors encounter repression more often in military regimes than in party regimes and monarchies (Böhmelt 2014; Carruthers 2001).

Indeed, military regimes are, in general, more likely to use repression. For instance, the military government in Thailand arrests journalists and activists who criticise the government (Simpson and Smits 2022). Moreover, the lack of social equality undermines the effectiveness of climate policies, as only the military profits from them (Simpson and Smits 2022). China, as a single-party regime, has been more likely to accept ENGOs than other autocracies (Böhmelt 2014). Political authorities have enabled the participation of civil society in their efforts to address climate change (Wang et al. 2017). The party structure enables local authorities and bureaucrats in China to influence government policy (Duckett and Wang 2017) so that local knowledge can contribute to climate policy effectiveness. Social movements, ENGOs, and media have contributed to awareness of climate change in China (Wang et al. 2017). Böhmelt (2014) illustrate that the number of ENGOs varies by subtype of autocracy. Simpson and Smits (2018, 2022) show in their case studies of Myanmar and Thailand that the influence of environmental movements and civil society on climate policy in Thailand has varied over time with political power structures. The military coup in 2014 again limited opportunities for civil society organisations (Simpson and Smits 2022). Although during military rule in Myanmar political rights such as freedom of media were banned and repression was used against ENGOs, with the turn to electoral autocracy and later democratisation, higher levels of political rights have offered ENGOs more possibilities to influence climate policy (Simpson and Smits 2018).

3 Methodology

This article separately examines data on CO2 emissions in democratic and nondemocratic countries worldwide from 1990 to 2020. Climate change has been recognised as a political problem only since the beginning of the last decade of the 20th century. To identify democracies and autocracies, we apply the regimes of the world typology (Lührmann et al. 2018), which classifies countries with multiparty and free and fair elections that fulfil the criteria of polyarchy as democracies and others as autocracies. This classification based on the electoral democracy conceptualisation enables us to examine the effect of the characteristics of further models of democracy, as all conceptualisations include contested elections (e.g., Coppedge et al. 2011). We consider only independent countries (Coppedge et al. 2021a; Pemstein et al. 2021) with at least 500,000 citizens (The World Bank Group 2021a). This article examines changes in CO2 emissions. Data on CO2 emissions per capita come from the World Development Indicators (The World Bank Group 2021b). Countries export pollution-intensive production processes abroad. For reasons of data availability, this analysis focuses on domestic CO2 emissions. Data on political institutions and government ideology come from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (Coppedge et al. 2021a; Pemstein et al. 2021). Vertical and horizontal accountability and political rights are captured by indicators developed by Lührmann et al. (2020) and the V‑Dem project. The operationalisation of democratic institutions is presented in Table 2. This measurement approach enables us to study the effects of democratic institutions separately.

Institutional aspects of autocracies are measured by indicators from Teorell and Lindberg (2019) based on V‑Dem indicators (Coppedge et al. 2021a; Pemstein et al. 2021). The hereditary, military, and ruling party dimension indices capture the extent to which the appointment and dismissal of the chief executive depend on hereditary succession, the military, or a single ruling party. The dichotomous indicators used in previous research cannot capture the fact that the influence of a single party, the military, or a hereditary council also varies within subtypes (Teorell and Lindberg 2019).

Our statistical analyses control for additional variables applied in similar studies. Population density and urban population (The World Bank Group 70,71,c, d) might contribute to CO2 emissions via consumption (Arvin and Lew 2011). Because emissions result mainly from economic activities, we consider the level of economic development measured by high-income country designation (under the World Bank classification) and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (The World Bank Group 2021e, Teorell et al. 2021). Following the environmental Kuznets curve theory (Grossman and Krueger 1995), a curvilinear effect of GDP per capita is considered. The GDP per capita is mean-centred to avoid problems with nonessential multicollinearity. Countries that depend on fossil fuels might be associated with higher CO2 emissions. We thus consider, using data from Haber and Menaldo (2011), the real value of petroleum, coal, and natural gas produced per capita income. There are mixed findings regarding the effect of international trade, captured based on trade openness (The World Bank Group 2021e). Institutional quality affects the ability of governments to adopt and implement climate policies; the political corruption index from McMann et al. (2016) is thus included as an indicator of political corruption.

Political institutions limit the government’s potential opportunities to implement policy change (Pinto 2013) and provide incentives for political (in)action. Governments retain some room for (in)action. Therefore, in contrast to similar research, this article controls government ideology to ascertain the influence of democratic and nondemocratic institutions. Left governments might be more willing than right governments to undertake the market interventions and changes to the economic system needed to address global warming (e.g., Harrison and Sundstrom 2010). The quantitative results are ambiguous (Jensen and Spoon 2011; Garmann 2014). Current right-wing populist parties share a common world view that encompasses nationalism, authoritarianism, and anti-elitism and uniformly rejects climate protection and questions the existence of global warming (e.g., the Trump administration and the government of Jair Bolsonaro; see Lockwood 2018). Jahn (2021) has shown that right-wing populist parties contribute to greenhouse gas emissions in European Union member states. Government ideology is captured by the share of experts who agree that the ideology or societal model that a government at least partially promotes is a nationalist/conservative/socialist government ideology (Tannenberg et al. 2019; Coppedge et al. 2021b), as the indicators of the extent to which a government promotes a specific ideology cannot be tested simultaneously because of multicollinearity. The results remain stable with both operationalisations.

4 Findings

This section investigates climate outcomes separately for democracies and autocracies. Emissions of CO2 vary more among countries (standard deviation [SD] 1.64) than over time (SD 0.28). This regularity also applies to democratic and nondemocratic institutions. There are considerable differences in the implementation of democratic institutions among both democracies and autocracies. Autocracies additionally differ in the extent of influence of hereditary succession, the military, and the party of the state on the chief executive.

To consider that democracy aspects might only affect long-term changes in CO2 emissions, we examine long- and short-term changes in climate outcomes. Moreover, recent studies indicate that democratic aspects affect variation in CO2 emissions across countries and over time differently (e.g., Clulow 2019). As democratic aspects and climate outcomes vary more among countries than over time, we expect that democratic institutions should perform better in explaining between-variation than within-variation. We examine between-variation in the long-term development of CO2 emissions using the linear trend of CO2 emissions per capita from 1990 to 2020 and country averages of the independent variables of cross-sectional regression models. This dependent variable also enables us to address endogeneity (Babones 2014). To consider model complexity, we estimate the final models with and without outliers and influential cases. Short-term variation within countries is examined based on a first differences model that examines annual changes in CO2 emissions per capita as the dependent variable and time-series cross-sectional data of the independent variables (Kittel and Winner 2005). The results remain stable if we use changes in CO2 emissions over a period of 2 or 5 years. The first differences models are estimated in a robustness analysis with income from fossil fuels, as data availability on this variable is limited. Positively skewed indicators are logarithmised.

4.1 Democracies

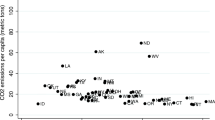

Democratic institutions contribute to the explanation of variation in the development of CO2 emissions in democracies (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The participation of civil society matters for country differences in the linear trend of CO2 emissions from 1990 to 2020. As expected, greater participation of civil society is associated with a negative trend in CO2 emissions. While quality of deliberation contributes to a positive trend in CO2 emissions, this effect becomes insignificant in the analysis of only non–high-income countries and the analysis without outliers and influential cases. Adding the indicators of democratic aspects contributes to the explanatory power of the regression model. Comparing standardised coefficients shows that the effect of civil society participation is more important for CO2 emissions than the effects of the controls. Among the controls, population density contributes to climate protection. When we exclude influential cases and outliers, nationalist government ideology is positively associated with CO2 emissions.

Democratic institutions and the linear trend in CO2 emissions in democracies. Standardised regression coefficients of model 2 in Table 3

Table 4 examines annual changes in CO2 emissions based on a first differences model. Among the controls, nationalist government ideology contributes to an increase in CO2 emissions. The negative effect of political rights is not significant in all model specifications. In contrast to the theoretical expectations, greater participation of civil society increases annual CO2 emissions (Fig. 2). Social equality contributes to lower annual CO2 emissions. Comparing the standardised coefficients, the effects of civil society participation and social equality are stronger than the effect of the controls.

Democratic institutions and annual changes in CO2 emissions in democracies. Standardised regression coefficients of model 5 in Table 3

4.2 Autocracies

Table 5 illustrates that the implementation of democracy aspects varies among autocracies. This justifies our approach to examine their effects on CO2 emissions. Nondemocracies with above-average values of party influence perform better on most measures associated with democratic aspects than autocracies with above-average values of hereditary or military rule. This is in accordance with our hypothesis that party rule should limit the influence of democratic incentives to a lesser extent than hereditary or military rule.

Table 3 displays the results for the linear trend of CO2 emissions in autocracies. Social equality contributes to CO2 emissions in autocracies. The positive effect of contested elections becomes insignificant in the analysis without influential cases and outliers. The extent of influence of the military on the chief executive is associated with a decrease in CO2 emissions. Local and regional democracy is associated with lower CO2 emissions. This effect is weaker than the positive effect of social equality (Fig. 3), and it is significant only in countries with below-average values of dependence of the chief executive on the military (Fig. 4). Hereditary rule and party rule have no significant interaction with social equality. The inclusion of democratic as well as nondemocratic aspects to the regression model increases its explanatory power. Among the controls, trade openness decreases and income from natural resources increases CO2 emissions. Income from natural resources is more important for climate outcomes than local and regional democracy or military rule.

Democratic and nondemocratic institutions and the linear trend in CO2 emissions in autocracies. Standardised regression coefficients of model 2 in Table 4

With regard to annual changes in CO2 emissions (Table 4 and Fig. 5), a greater influence of the ruling party on the chief executive is associated with an increase in CO2 emissions. Social equality decreases emissions growth. Civil rights contribute to an increase in CO2 emissions. The democratic and nondemocratic aspects are more important for annual changes in CO2 emissions than the controls. The negative effect of social equality is significant only in countries with below-average values of party or military rule (Figs. 6 and 7). These models control for income from fossil fuels; without this control variable and, therefore, more country-years, the effects apply for all values of party or military rule. While emissions increase with military influence, they decrease with the influence of the ruling party.

Democratic and nondemocratic institutions and annual changes in CO2 emissions in autocracies. Standardised regression coefficients of model 5 in Table 4

4.3 Discussion of the Results

In the theoretical literature, there is no agreement on the climate consequences of models of democracy. Our argument has been that among the democratic aspects, political rights, quality of deliberation, participation of civil society, local and regional democracy, and social equality in particular might contribute to climate protection, as these institutions help coordinate diffuse interests in the political decision-making process. The findings first partly support this hypothesis. In democracies, specific institutions of participatory and egalitarian democracy—civil society participation and social equality—matter for country differences in the linear trend of CO2 emissions from 1990 to 2020 and for annual CO2 emissions. In autocracies with local and regional quality of democracy, another aspect of participatory democracy affects climate outcomes. Democratic institutions have independent effects of government ideology on climate outcomes. The findings also remain stable if we control for the influence of presidential systems. In contrast to the hypotheses, there are no significant negative effects of political rights or quality of deliberation. It is important to consider that democratic institutions that coordinate diffuse interests in the political system, such as political rights, also enable opponents of climate protection to influence public opinion and undermine climate policy.

Second, democratic effects on CO2 emissions vary among democracies and autocracies. Thus, it is important to consider that the context in autocracies affects the responsiveness of governments to democratic incentives. The findings support our assumption that nondemocratic institutions affect the responsiveness of autocratic governments to incentives from democratic institutions. There is some support for the hypothesis that one-party rule limits the effects of democratic institutions less than the influence of other nondemocratic institutions. Military rule limits the effect of local and regional democracy on country differences in the linear trend in CO2 emissions and the negative effect of social equality on annual changes in CO2 emissions. In contrast to our hypothesis, the negative effect of social equality on annual changes in CO2 emissions becomes even stronger with the degree of dependence of the executive on party rule.

Third, as expected, the explanatory models perform better in the explanation of long-term variation in climate outcomes among countries than annual changes in climate outcomes within countries. Nonetheless, democratic institutions also affect short-term changes in CO2 emissions. The negative effects of civil society participation and social equality on CO2 emissions in democracies support our hypothesis that democratic institutions support diffuse interests such as climate protection in the political decision-making process. Simultaneously, civil society participation is associated with an increase in annual CO2 emissions in democratic countries. Civil society participation also enables opponents of climate protection to influence government policy. Therefore, it might decrease CO2 emissions only in the long term because the formation of ENGOs and the development of an independent civil society take time (Fredriksson and Neumayer 2013).

In autocracies, local and regional democracy is associated with a lower long-term trend in CO2 emissions, and social equality decreases annual changes in emissions. While social equality decreases CO2 emissions in the short term, autocracies with higher levels of social equality are associated with higher levels of CO2 emissions. Wu and Xie (2020) observe that inequality contributes in the long run to lower CO2 emissions. Equality contributes via increases in consumption, energy use, economic power, and capital accumulation to emissions. In accordance, among democratic institutions, social equality correlates strongly with economic development in autocracies.

5 Conclusion

Democratic institutions that coordinate diffuse interests can provide incentives for both democratic and autocratic governments to reduce climate emissions. The results offer some evidence that such democratic institutions matter for climate outcomes in democracies and autocracies. The participation of civil society and social equality contribute to lower CO2 emissions in democracies. In autocracies, social equality and local and regional democracy are associated with a decline in CO2 emissions. Nondemocratic institutions affect responsiveness to diffuse interests such as climate protection in autocracies. The extent of influence of the military weakens the climate consequences of democratic institutions. In contrast, the dependence on a ruling party strengthens the negative effect of social equality on annual changes in CO2 emissions in autocracies.

Considering that the effects of democratic institutions on CO2 emissions vary among democracies and autocracies at both the cross-national and temporal levels and with respect to moderator variables, the findings illustrate that the relationship between democratic institutions and climate outcomes is context dependent. Thus, future research could use in-depth case studies to improve our understanding of the causal mechanisms that link these democratic dimensions to climate protection. Second, the climate consequences of democratic institutions are partly dependent on the institutional context in autocratic regimes. Further studies could examine whether nondemocratic institutions also affect other dimensions of sustainability. Moreover, the effects of political institutions might be clearer for climate policy output, as climate outcomes are affected by various nonpolitical variables.

References

Adam, Simpson, and Mattijs Smits. 2018. Transitions to energy and climate security in southeast asia? Civil society encounters with illiberalism in Thailand and Myanmar. Society & Natural Resources 31(5):580–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1413720.

Arias-Maldonado, Manuel. 2007. An imaginary solution? The green defence of deliberative democracy. Environmental Values 16(2):233–252. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327107780474573.

Arvin, B. Mak, and Byron Lew. 2011. Does democracy affect environmental quality in developing countries? Applied Economics 43(9):1151–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840802600277.

Babones, Salvatore J. 2014. Methods for quantitative macro-comparative research. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Bättig, Michèle B., and Thomas Bernauer. 2009. National institutions and global public goods: Are democracies more cooperative in climate change policy? International Organization 63(2):281–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818309090092.

Beeson, Mark. 2010. The coming of environmental authoritarianism. Environmental Politics 19(2):276–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010903576918.

Bernauer, Thomas, and Vally Koubi. 2009. Effects of political institutions on air quality. Ecological Economics 68(5):1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.003.

Bernauer, Thomas, Tobias Böhmelt, and Vally Koubi. 2013. Is there a democracy-civil society paradox in global governance? Global Environmental Politics 13(1):88–107. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00155.

Böhmelt, Tobias. 2014. Political opportunity structures in dictatorships? Explaining ENGO existence in autocratic regimes. Journal of Environment & Development 23(4):446–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496514536396.

Böhmelt, Tobias, Marit Böker, and Hugh Ward. 2016. Democratic inclusiveness, climate policy outputs, and climate policy outcomes. Democratization 23(7):1272–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1094059.

Bueno De Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. 2003. The logic of political survival. Cambridge, London: MIT Press.

Burnell, Peter. 2012. Democracy, democratization and climate change: complex relationships. Democratization 19(5):813–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2012.709684.

Carbonell, Joel R., and Juliann E. Allison. 2015. Democracy and state environmental commitment to international environmental treaties. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 15(2):79–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9213-6.

Carruthers, David. 2001. Environmental politics in Chile: legacies of dictatorship and democracy. Third World Quarterly 22(3):343–358.

Cheibub, José Antonio, Jennifer Gandhi, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2010. Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice 143(1–2):67–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2.

Christoff, Peter, and Robyn Eckersley. 2011. Comparing state responses. In Oxford handbook of climate change and society, ed. John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard, and David Schlosberg, 431–448. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clulow, Zeynep. 2019. Democracy, electoral systems and emissions: explaining when and why democratization promotes mitigation. Climate Policy 2019(2):244–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1497938.

Congleton, Roger D. 1992. Political institutions and pollution control. The Review of Economics and Statistics 74(3):412–421. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109485.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Steven Fish, and Allen Hicken. 2011. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: A new approach. Perspectives on Politics 9(2):247–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000880.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, and Jan Teorell. 2021a. V‑Dem [Country—Year/Country—Date] Dataset v11.1. Varieties of democracy (V-Dem). Project https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds21.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, and Jan Teorell. 2021b. V‑Dem Codebook v11.1. Varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project. https://www.v-dem.net/static/website/img/refs/codebookv111.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2021.

Cushing, Lara, Rachel Morello-Frosch, Madeline Wander, and Manuel Pastor. 2015. The haves, the have-nots, and the health of everyone: The relationship between social inequality and environmental quality. Annual Review of Public Health 36:193–209. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122646.

Dryzek, John S. 1987. Rational ecology: Environment and political economy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dryzek, John S. 1992. Ecology and discursive democracy: Beyond liberal capitalism and the administrative state. Capitalism Nature Socialism 3(2):18–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455759209358485.

Duckett, Jane, and Guohui Wang. 2017. Why do authoritarian regimes provide public goods? Policy communities, external shocks and ideas in China’s rural social policy making. Europe-Asia Studies 69(1):92–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2016.1274379.

Eckersley, Robyn. 1995. Liberal democracy and the rights of nature: The struggle for inclusion. Environmental Politics 4(4):169–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019508414232.

Escher, Romy, and Melanie Walter-Rogg. 2018. Does the conceptualization and measurement of democracy quality matter in comparative climate policy research? Politics and Governance 6(1):117–144. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i1.1187.

Escher, Romy, and Melanie Walter-Rogg. 2020. Environmental performance in democracies and autocracies: democratic qualities and environmental protection. Cham: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38054-0.

Fredriksson, Per G., and Eric Neumayer. 2013. Democracy and climate change policies: Is history important? Ecological Economics 95:11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.08.002.

Fredriksson, Per G., and Le Wang. 2011. Sex and environmental policy in the U.S. House of Representatives. Economics Letters 113:228–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.07.019.

Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. 2007. Authoritarian institutions and the survival of autocrats. Comparative Political Studies 40(11):1279–1301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414007305817.

Garmann, Sebastian. 2014. Do government ideology and fragmentation matter for reducing CO2-emissions? Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Ecological Economics 105:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.05.

Gilley, Bruce. 2012. Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environmental Politics 21(2):287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.651904.

Grossman, Gene M., and Alan B. Krueger. 1995. Economic growth and the environment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(2):352–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118443.

Haber, Stephen H., and Victor A. Menaldo. 2011. Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A reappraisal of the resource curse. American Political Science Review 105(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000584.

Hadenius, Axel, and Jan Teorell. 2007. Pathways from authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy 18(1):143–156. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2007.0009.

Hadenius, Axel, Jan Teorell, and Michael Wahman. 2017. Authoritarian regimes data set, version 6.0 codebook. https://xmarquez.github.io/democracyData/reference/wahman_teorell_hadenius.html. Accessed 1 July 2021.

Hamilton, Clive. 2010. Requiem for a species. Why we resist the truth about climate change. London, Washington: Earthscan.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. The tradegy of the commons. Science 162:1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

Harrison, Kathryn, and Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom. 2010. Introduction: Global commons, domestic decisions. In Global commons, domestic decisions. The comparative politics of climate change, ed. Kathryn Harrison, Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom, 1–22. Cambridge, London: MIT Press.

Held, David, and Angus Hervey. 2011. Democracy, climate change and global governance: Democratic agency and the policy menu ahead. In The governance of climate change. Science, economics, politics and ethics, ed. David Held, Angus Hervey, and Marik Theros, 89–110. Cambridge, Malden: Polity Press.

Jahn, Detlef. 2021. Quick and dirty: how populist parties in government affect greenhouse gas emissions in EU member states. Journal of European Public Policy 28(7):980–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918215.

Jensen, Christian B., and Jae-Jae Spoon. 2011. Testing the ‘party matters’ thesis: Explaining progress towards Kyoto Protocol targets. Political Studies 59(1):99–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00852.x.

Kim, Doo-Rae, and Jong-Han Yoon. 2018. Decentralization, government capacity, and environmental policy performance: A cross-national analysis. International Journal of Public Administration 41:1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2017.1318917.

Kittel, Bernhard, and Hannes Winner. 2005. How reliable is pooled analysis in political economy? The globalization-welfare state nexus revisited. European Journal of Political Research 44(2):269–293.

Larson, Anne M., and Fernanda Soto. 2008. Decentralization of natural resource governance regimes. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 33:213–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.environ.33.020607.095522.

Leggewie, Claus, and Harald Welzer. 2008. Can democracies deal with climate change. https://www.eurozine.com/can-democracies-deal-with-climate-change/. Accessed 22 Jan 2019.

Lockwood, Matthew. 2018. Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics 27(4):712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411.

Lührmann, Anna, Valeriya Mechkova, Sirianne Dahlum, Laura Maxwell, Moa Olin, Constanza Petrarca, Rachel Sigman, Matthew Wilson, and Staffan Lindberg. 2018. State of the world 2017: Autocratization and exclusion? Democratization 25:1321–1340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1479693.

Lührmann, Anna, Kyle L. Marquard, and Valeriya Mechkova. 2020. Constraining governemnts: New indices of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal accountability. American Political Science Review 114(3):811–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000222.

Mayer, Adam. 2017. Will democratization save the climate? An entropy-balanced, random slope study. International Journal of Sociology 47(2):81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2017.1300465.

McCright, Aaron M., and Riley E. Dunlap. 2011. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change 21:1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003.

McMann, Kelly, Daniel Pemstein, Brigitte Seim, Jan Teorell, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2016. Strategies of validation: Assessing the varieties of democracy corruption data. Working Paper, Vol. 23. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, The Varieties of Democracy Institute and Department of Political Science.

Merkel, Wolfgang. 2004. Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization 11(5):33–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340412331304598.

Miller, David. 1992. Deliberative democracy and social choice. Political Studies 40:54–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1992.tb01812.x.

Ophuls, William. 1977. Ecology and the politics of scarcity: Prologue to a political theory of the state. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Wang Yi-ting, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von Römer. 2021. The V‑Dem measurement model: latent variable analysis for cross-national and cross-temporal expert-coded data, 6th edn., V‑Dem working paper, Vol. 21. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Pinto, Pablo M. 2013. Partisan investment in the global economy. Why the left loves foreign direct investment and FDI loves the left. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Povitkina, Marina. 2018. The limits of democracy in tackling climate change. Environmental Politics 27(3):411–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1444723.

Schmitter, Philippe C., and Nadine Sika. 2017. Democratization in the Middle East and North Africa: A more ambidextrous process? Mediterranean Politics 22:443–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2016.1220109.

Selseng, Torbjorn, Kristin Linnerud, and Erling Holden. 2022. Unpacking democracy: The effects of different democratic qualities on climate cange performance over time. Environmental Science and Policy 128:326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.12.009.

Shearman, David, and Joseph Wayne Smith. 2007. The climate change challenge and the failure of democracy. Westport, London: Praeger.

Simpson, Adam, and Mattijs Smits. 2022. Climate change governance and (il)liberalism in Thailand: activism, justice, and the state. In Governing climate change in southeast Asia. Critical perspectives, ed. Jens Marquardt, Laurence L. Delina, and Mattijs Smits, 168–186. Oxford, New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429324680.

Stadelmann-Steffen, Isabelle. 2011. Citizens as veto players: Climate change policy and the constraints of direct democracy. Environmental Politics 20:485–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2011.589577.

Stier, Sebastian. 2015. Democracy, autocracy and the news: the impact of regime type on media freedom. Democratization https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.964643.

Tannenberg, Marcus, Michael Bernhard, Johannes Gerschewski, Anna Lührmann, and Christian von Soest. 2019. Regime Legitimation Strategies (RLS) 1900 to 2018. V‑Dem working paper series, Vol. 2019(86)

Teorell, Jan, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2019. Beyond democracy-dictatorship measures: A new framework capturing executive bases of power, 1789–2016. Perspectives on Politics 17(1):66–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718002098.

Teorell, Jan, Aksel Sundström, Sören Holmberg, Bo Rothstein, Natalia Alvarado Pachon, and Cem Mert Dalli. 2021. The quality of government standard dataset, version Jan21. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, The Quality of Government Institute. https://doi.org/10.18157/qogstdjan21.

The World Bank Group. 2021a. Population, total. World development indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL. Accessed 1 June 2021.

The World Bank Group. 2021b. CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita). World development indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC. Accessed 1 June 2021.

The World Bank Group. 2021c. Urban population. World development indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL. Accessed 1 June 2021.

The World Bank Group. 2021d. Urban population. World development indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST. Accessed 1 June 2021.

The World Bank Group. 2021e. GDP per capita (2010 constant US dollar). World development indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD. Accessed 1 June 2021.

UNEP. 2016. Global gender and environment outlook 2016. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/176245/176245.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2021.

Von Stein, Jana. 2020. Democracy, autocracy, and everything in between: How domestic institutions affect environmental protection. British Journal of Political Science 52(1):339–357. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342000054X.

Wang, Pu, Lei Liu, and Tong Wu. 2017. A review of China’s climate governance: state, market and civil society. Climate Policy 18(5):664–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1331903.

Ward, Hugh. 1996. Green arguments of local democracy in the United States. In Rethinking local democracy, ed. Desmond King, Gerry Stoker, 130–157. Houndmills: Macmillan.

Ward, Hugh, Xun Cao, and Bumba Mukherjee. 2014. State capacity and the environmental investment gap in authoritarian states. Comparative Political Studies 47(3):309–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013509569.

Winslow, Margrethe. 2005. Is democracy good for the environment? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 48(5):771–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560500183074.

Wu, Rong, and Zihan Xie. 2020. Identifying the impacts of income inequality on CO2 emissions: Empirical evidences from OECD countries and non-OECD countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 277:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123858.

Wurster, Stefan. 2013. Comparing ecological sustainability in autocracies and democracies. Contemporary Politics 19(1):76–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2013.773204.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors of the special issue, Thomas Dietz, Doris Fuchs, Armin Schäfer, and Antje Vetterlein; two anonymous reviewers; and Peter Drahos for their helpful comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R. Escher and M. Walter-Rogg declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Escher, R., Walter-Rogg, M. The Effects of Democratic and Nondemocratic Institutions on CO2 Emissions. Polit Vierteljahresschr 64, 715–740 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-023-00458-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-023-00458-2

Keywords

- Climate policy

- Democracy

- Autocracy

- Institutions

- Climate change

- Social equality

- Civil society participation