Abstract

The work-family literature suggests a contradictory relationship between working parenthood and (good) childhood, with disruptive or neglected children on the one side and absent or overburdened parents on the other. While the child occupies a complicated space in this relation, their position is rarely examined. Against this background, I explore the position of the child by turning to children’s co-presence during parents’ performance of home-based paid work and ask how parents construct the child and their corresponding parental responsibilities. Following a practice-theoretical framework, I approach parents’ accounts as practices of representation in which the boundaries of what was perceived as (not) acceptable ways of doing family and work were sketched out.

For this purpose, I analysed 25 qualitative interviews with and about home-based working parents in the Austrian creative industries with positional maps. The parents had between one and three children in kindergarten or primary school.

Parents’ constructions of the child were complex and ambiguous, as were the corresponding parental responsibilities. Meeting the child’s needs and not harming the child emerged as a common ground, yet the parents’ commitment to paid work was not questioned. Conversely, home-based work was seen as a way to meet both work and care demands. These findings suggest that home-based work may bridge ideas of good childhood and working parenthood. The paper contributes to an understanding of work and family that goes beyond simple dualism and offers new insights into parental home-based work, which remains relevant in the post-pandemic era.

Zusammenfassung

Die Literatur zu Arbeit und Familie verweist auf widersprüchliche Beziehungen zwischen berufstätiger Elternschaft und (guter) Kindheit, mit störenden oder vernachlässigten Kindern auf der einen und abwesenden oder überlasteten Eltern auf der anderen Seite. Obwohl das Kind in dieser Beziehung einen zentralen Platz einnimmt, wird seine Position nur selten berücksichtigt. Vor diesem Hintergrund wende ich mich der Kopräsenz von Kindern während der elterlichen Erwerbsarbeit zu Hause zu und frage, wie Eltern das Kind und ihre jeweilige elterliche Verantwortung konstruieren. Im Rahmen eines praxistheoretischen Ansatzes betrachte ich die Äußerungen der Eltern als Praktiken der Repräsentation, in denen die Grenzen abgesteckt werden, was als (nicht) akzeptabler Umgang mit Arbeit und Familie gilt.

Hierfür wurden 25 qualitative Interviews mit und über zu Hause arbeitende Eltern in der österreichischen Kreativwirtschaft mit Hilfe von Positionsmaps analysiert. Die Eltern hatten zwischen einem und drei Kindern im Kindergarten- oder Volksschulalter.

Die Konstruktionen der Eltern vom Kind waren komplex und mehrdeutig, sowie die entsprechenden elterlichen Verantwortlichkeiten. Den Bedürfnissen des Kindes gerecht zu werden und ihm nicht zu schaden, erwies sich als Basis, ohne dass die Berufstätigkeit der Eltern in Frage gestellt wurde. Umgekehrt wurde die häusliche Erwerbstätigkeit als Möglichkeit gesehen, sowohl den Anforderungen der Arbeit als auch denen der Kinderbetreuung gerecht zu werden. Diese Ergebnisse implizieren, dass häusliche Erwerbstätigkeit eine Brücke zwischen Vorstellungen guter Kindheit und berufstätiger Elternschaft schlagen kann. Der Beitrag trägt zu einem Verständnis von Arbeit und Familie, jenseits von Dualismen bei, und bietet neue Einblicke in die häusliche Erwerbstätigkeit, die auch nach der Pandemie relevant bleibt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

“And it’s especially difficult with [5-year-old child] […] when making phone calls. […] And then when [the child] is yelling in the back […]. Then I often don’t know what to do. Because then I lock myself in the bedroom and she knocks on the door and on the phone, she says: ‘What’s going on?’ And afterwards I am always quite angry on the one hand, but on the other hand I understand.” (home-based working mother, 35–40 years old)

“[The 5‑year-old child] was sick, had a fever. And I prepared a bed for him on the floor behind me and he lay behind me all day listening to an audiobook or reading something or sleeping. And I worked next to him. That was great. It wasn’t that efficient, but still.” (home-based working father, 35–40 years old)

These two quotes introduce the focus on work-family relations that I take in this article: the co-presence of children during parents’ performance of home-based paid work. I approach home-based work as paid work performed in the home (Gough 2012), not as an exceptional situation due to a global pandemic, but as a permanent arrangement. With this focus, I explore the co-constitutive position of the child in work-family relations. However, the child occupies a complicated space in this relation, and at the same time, their position is rarely examined (Perry-Jenkins and Gerstel 2020).

First, in both work and family studies, the work-family nexus has been addressed through notions of reconciliation, balance, fit, conflict, or enrichment and their implications for the roles and well-being of family members, with a focus on mothers with (young) children (Collins 2020; Gatrell et al. 2013; Hochschild 2001; Voydanoff 2005). Work and family are often seen as two different spheres that require individuals—usually adults engaged in paid work—to do boundary work to separate or integrate work and family on a spatial, temporal, or mental level (Clark 2000; Nippert-Eng 1996). Moreover, research on home-based work, which has kept being revitalised in response to technological changes since the end of the 20th century, has approached home-based work as a flexible and potentially family-friendly work mode (Homberg et al. 2023; Messenger and Gschwind 2016). While home-based work has been considered a solution for women to better reconcile work and family, research has shown ambiguous implications with respect to gender equality (Chung and van der Horst 2018; Hilbrecht et al. 2008; Lott and Abendroth 2020; Mirchandani 2000; Sullivan and Lewis 2001). This strand of research, with its focus on adults, perceives the child as a constraint, particularly for women, on meeting both work and family demands. This understanding of the child—as a burden, a disadvantage, or a disruption—is one-dimensional and denies the child a productive position in work-family relations.

Second, a similar—but reversed—picture emerges in research that explores children’s situation in relation to parents’ paid work: parental employment, especially that of mothers (Hays 1998; Schmidt et al. 2023; Wall 2013), is portrayed as a constraint on children’s lives. Central to this perspective is the assumption that family time and thus children’s opportunities to be at home—which is imagined as the child’s natural space (Cieraad 2013)—are limited by adults’ (work) schedules and work-related constraints (e.g., Harden et al. 2013; Zeiher 2005). The construction of working parenthood as the antithesis of a good childhood is thus intertwined with middle-class ideals about family time as quality time free from obligation (Daly 2001). Sociological interest in childhood and children’s positions in work-family relations, which had momentum at the turn of the millennium (Galinsky 1999; Harden et al. 2013; Pimlott-Wilson 2012), has declined (Perry-Jenkins and Gerstel 2020; Reimann et al. 2022); current research is more likely to examine the impact of parents’ (non-standard) work on children’s well-being and development (Pollmann-Schult and Li 2020). Thus, a critical examination of the image of the child and the working parent remains underexplored in current research on work-family relations.

While the literature review suggests a conflicting relation between working parenthood, family, and good childhood, with a disruptive or neglected child on the one hand and an absent or overburdened parent on the other, the above quotes illustrate the diverse positions that children can occupy, ranging from disruptive (shouting, knocking) to enabling (listening to an audiobook, reading, sleeping). Similarly, the working parent is constructed as being clueless, angry, understanding, caring, or working (in)efficiently. Julie Seymour (2007) argues that examining the atypical and minor situation of family life at the single-location home/workplace opens up possibilities for making explicit and challenging taken-for-granted ideas that shape the family—such as work and family as distinct and competing spheres. In her studies, therefore, Seymour (2007, 2010) shows that children, both as social actors and as discursive figures, take a central part in the ways in which family is done and displayed in relation to home-based work. Similarly, Karen Handley (2023) argues that the removal of the physical separation between work and family during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns opened up space for working mothers to destabilise dominant discursive assumptions of intensive parenting.

Against this background, I aim to widen the dominant perspectives on work-family relations and home-based work by turning to understandings of the child and parents’ responsibilities. However, the focus of this paper is not on the voices or perspectives of children, but on the conditions of possibility that shape childhood and parenthood at this specific intersection of work and family. To this end, I ask how parents construct the child and their corresponding parental responsibilities in the particular work-family arrangement of home-based work and the resulting co-presence of children. In order to answer these questions, I draw upon 25 qualitative interviews with and about home-based working parents in the Austrian creative industries. Following a practice-theoretical framework, I approach parents’ accounts as practices of representation in which the boundaries of what was perceived as (not) acceptable ways of doing family and work were sketched out. In this paper, I aim to first bring together strands of work and family studies with childhood studies in order to overcome antagonisms between work and family. Second, I offer new insights into home-based work, which is of high relevance in the post-pandemic era, when home-office days among employees have increased in popularity (Bachmayer and Klotz 2021). In doing so, I suggest that home-based work, and in particular parents’ engagement in paid work in the co-presence of children, may not (only) contradict but rather bridge ideas of good childhood and working parenthood.

Following this research interest, I first outline the theoretical framework of the paper (Sect. 2). Then, I present the research setting, empirical data, and methodology (Sect. 3). In the results section, I present the reconstructed discursive positions (Sect. 4) that I summarise and discuss in the final section (Sect. 5).

2 Approaching family, childhood, and (working) parenthood as practice/discourse formation

In this section, I first present the family practices approach in combination with practice theories as a theoretical framework. Second, I discuss conceptual perspectives on the child and childhood as a construction.

2.1 Discursive dimensions of family practices

Theoretically, I build on concepts that understand family through everyday life and as practices of doing family (Morgan 2011) and embed this family practice approach in a practice-theoretical framework (Reckwitz 2002).

While Morgan (2011, p. 68) views the family as a set of practices, he also points out that “practices and discourses, the families we live with and the families we live by, are mutually implicated in each other”. Furthermore, Morgan (2011, pp. 60f.) contends that “family members reflexively create and reproduce their identities and relationships”, particularly “in an environment which, to an external gaze, might seem much removed from the expectations of family life”—such as when working from home in the co-presence of a child.

In a similar vein, Reckwitz (2016) integrates, with the notion of practice/discourse formation, the concept of discourse into practice-theoretical thinking by drawing from Foucault’s (1981) distinction between discursive and non-discursive practices. Discursive practices are “practices of representation” in which “objects, subjects, relations are represented in a specific, regulated way and in this representation are produced as specific meaningful entities in the first place” (Reckwitz 2016, p. 62, own translation). Thus, codes that classify what is (not) sayable, thinkable, and possible become visible in discursive practices.

2.2 Constructions of the child and their implications

Since its founding in the 1980s, childhood studies has become a diverse and interdisciplinary field concerned with “the concept of the child as an agent in generational orders who actively shapes her or his social relationships” (Honig 2016, p. 70) and understanding childhood as a social construction that is historically embedded. It has therefore been central to address the question of what a child is, and consequently what childhood is, and how these understandings both shape children’s social position and are interrelated with wider social structures along lines of class, gender, or race (Jenks 1996; Smith 2012).

Childhood researchers (Jenks 1996; Smith 2012) have thus turned to the figure of the child and how it changes historically in interaction with political models and power/knowledge, tracing development from the wild and evil child through the image of the natural and innocent child to the agentic and responsible child. Depending on the image of the child, there are demands for (self-) control, discipline, or protection in order to make children fit into society. Although these images are historically grounded, they transcend time and culture, which means that “strategies for governing childhood” (Smith 2012, p. 34) are shaped by many different (and contradictory) images of the child. Furthermore, a critical examination of childhood as a time of innocence, which can be found throughout the different images of the child, has been central to the field (Smith 2012). Researchers have pointed out that innocence is a construction “founded on fixed, adultcentric, white, Eurocentric, gendered, middle-class values” (Robinson 2008, p. 115). Innocence has thus been used to legitimise both the separation of children from adult society and interventions in childhoods that do not conform to this ideal (Bühler-Niederberger 2005). In line with the understanding of childhood as a time to be protected from the adult world, Harden et al. (2013, p. 308) point out that the aspirations to “be there” and “be together” that characterise contemporary understandings of good or ideal parenting and family are at odds with notions of working parenthood.

These constructions of the child and the corresponding normative understandings of childhood hold thus norms that also assign adults—including parents—a specific position (Smith 2012; Wall 2013). In this vein, researchers in the field of parenting cultures have described parents’ increased responsibilisation for children’s well-being in the prospect of children’s development and future outcomes in Europe and beyond (Dermott and Pomati 2016; Lee et al. 2014; Ostner et al. 2016). A gender perspective emphasises that the load of responsibility falls especially on mothers. This has been conceptualised as intensive mothering, which constructs childrearing as a labour- and time-intensive, emotionally fulfilling, and child-centred endeavour (Hays 1998). The dominance of children’s need for supervision, guidance, and direction has thus been seen to limit the “space for women’s equality in the workplace and family” (Wall 2013, p. 170). However, in their scoping review of two decades of research on motherhood, Eva-Maria Schmidt et al. (2023) identify five social norms around motherhood: the norms of being attentive to the child, securing the child’s successful development, integrating employment into mothering, being in control, and being contented. Furthermore, the authors point out—in line with others (e.g., Elliot et al. 2015)—that ideals of motherhood are rooted in heteronormative, White, middle-class values that make them unattainable for many mothers and legitimise the control of motherhood that deviates from them, usually along class, race, and gender lines. In other words, privileged parents are “setting the tone and standard in terms of key markers of educationally ‘appropriate’ and ‘supportive’ parenting” (Dermott and Pomati 2016, p. 138).

By asking about parents’ constructions of the child and the corresponding parental responsibilities, I turn to the “cultural typologies, catalogues of requirements, and at the same time patterns of what is desirable” (Reckwitz 2021, p. 191). In other words, with the analytical focus on the discursive dimension, I examine the kind of family life the research participants wanted (not) to pursue and the family members they wanted (not) to be and, in doing so, sketched out the boundaries of what were perceived as acceptable ways of doing family and work.

3 Data and methods

This paper is based on data that I collected for my doctoral research project, When Home Is a Workplace, which focuses on family life with children and home-based working parents in the Austrian creative industries.Footnote 1 In this section, I describe first the research setting and participants, and second, the data collection and analysis that were central to this paper.

3.1 Research setting and participants

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, working from home was not a common practice in Austria. In 2019, 9.9% of workers typically and 12.1% occasionally worked from home, collectively representing 22% (Bock-Schappelwein et al. 2020). However, the creative industries have been characterised by a high proportion of atypical forms of work, including home-based work (Eichmann 2010; Kreativwirtschaft Austria 2017): More than 60% of all companies are single-person enterprises, with over half of them working from home (Kreativwirtschaft Austria 2013, 2023). Sociological studies about Vienna’s creative industries in the mid-2000s and 2010s emphasised the precarious nature of the sector, which is characterised by the blurring between work and non-work times, people, and places (Eichmann 2010). All this qualified creative work as the sector to focus on when researching family life in relation to home-based work.

The main criteria for the sample were that an adult participant had to be both a parent and a home-based worker in one of the fields of the Austrian creative industries, and that there had to be at least one child between the ages of 3 and 10 in the same household. This criterion was set because children in this age group (still) need to be permanently supervised by an adult but are also likely or required to attend day care or school. However, the study’s multi-perspective focus on family meant that family members, such as cohabiting partners/parents or other children outside the target age range, were to be included in the research whenever possible.

I recruited families via friends and colleagues who distributed my request to their networks and by posts in Facebook groups. The sample comprised 11 families from two Austrian cities with 40 family members, including 20 parents in a heterosexual couple relationship and one single mother as well as 19 children (2–17 years old). In each family lived between one and three children; 13 children were in the targeted age of being in kindergarten (eight children) or primary school (four children), two children were under the age of 3 and were looked after at home, and four children went to secondary school. In this paper, I focus on interviews with the adult family members,Footnote 2 who can be described as White middle class: all were born in Austria or its neighbouring countries (Germany and Slovenia) and had a university degree or comparable vocational training, which reflects the high share of highly educated people in the creative industries (European Union 2019). The adults were between 30 and 55 years old, and all held gainful employment. Fifteen of them were home-based workers (eleven women, four men); in six families, only women, and in four families, both parents were working from home.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

Data collection took place from March 2018 to April 2019. I used two different qualitative interviews with the adult family members: problem-centred interviews (Witzel 2000) and photo-interviews (Kolb 2008) that I combined with a socio-spatial network game (Schier et al. 2015). The former was carried out at the very beginning of the data collection with only the home-based working parents (nine mothers and two couples in a joint interview, n = 11 interviews) and included open-ended questions about the family, living, and working situation as well as the history, current situation, and evaluation of home-based work. The latter was conducted with all available adult family members (nine home-based working mothers, two home-based working fathers, and three fathers who worked outside the home, n = 14 interviews), meaning that most of the home-based working parents were interviewed twice. The photo interviews focused on the home as the location where the family members lived and where home-based work was carried out and consisted of a tour of the flat or house, during which the family member took photos of different places in the home. These interactive and visual elements of the interview were used to sensitise the research participants to the spatial and temporal aspects of everyday life; therefore, only the verbal accounts were analysed further. In both types of interviews, children’s co-presence during the parents’ performance of paid work was discussed, and thus, both types of interviews hold constructions of the child and of corresponding parental responsibilities.

The exposé for the doctoral thesis comprised a separate section on research ethics that the doctoral advisory board of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Vienna approved. With the research participants’ permission, all interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and all personal data anonymised. The transcripts were indexed, and the analysis was managed using the MAXQDA software. All interviews were conducted in German, and the quotes used in the paper were translated by the author.

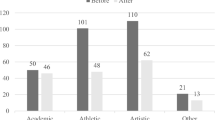

In the analyses of the interviews, I used positional maps, one of three mapping strategies in situational analysis (Clarke et al. 2018). With these maps, researchers focus on the discursive dimension by examining the positions taken and not taken around an issue by both mapping and memoing. To create the map (see Fig. 1), I collected all statements concerning children’s co-presence during parents’ performance of paid work. In a first step, the central dimensions of the issue were reconstructed to work as axes of the map. In a second step, the statements were reconstructed to distilled discursive positions in relation to the axes. In a third step, missing positions were reconstructed for those areas of the map where no articulated position could be found in the data. Positional maps facilitated the understanding that there was not a single or dominant but multiple overlapping and interlinked ideas associated with working in children’s co-presence and thus multiple constructions of the child and the corresponding parental responsibilities.

4 Findings: bridging childhood and working parenthood through home-based work

While the home-based working parents attempted to work when their children were at kindergarten or school, they could not (completely) avoid working in their children’s presence. This was for different reasons: on the one hand, they had to finish their work because of a deadline or because clients, colleagues, or bosses requested their work and formal childcare services did not match parents’ flexible working hours; on the other hand, like most parents in Austria, they preferred half-day childcare, supplemented by family care (Baierl and Kaindl 2021), which was mainly provided by the home-based working parent. Furthermore, children sometimes had to be looked after at home because they were sick or not yet in a childcare institution. The co-presence of children during their parents’ performance of home-based work was thus presented as a common, yet specific, element of daily family life.

The interviewed parents did not primarily raise the question of whether or not it was possible to work in the presence of children—because they had done so (even against all odds)—but rather under what circumstances it was (not) acceptable. In discussing this issue, parents made explicit their construction of the child as well as their understanding of parental responsibility towards the child, but also their work, both of which shaped what was seen as an appropriate way of handling the co-present child. In this way, ideas of a good childhood and parenting were assessed and linked to home-based work. However, as I argue, not necessarily in an antagonistic way.

To analyse parents’ discursive constructions, I reconstructed five positions that I mapped along two axes (see Fig. 1): on the vertical axis, I depicted the characterisation of the child on a continuum from dependent to independent, which, as can be seen in the discussion of the positions, was not linked to the child’s age. On the horizontal axis, I present the evaluation of working in the presence of children as a continuum from unacceptable to acceptable. In what follows, I discuss these positions by illustrating them with empirical examples and grouping them into three clusters. In addition, by pointing out two missing positions, I highlight what research participants did not include in their accounts. These findings represent the heterogeneous discursive positions (not) taken by parents and not a fixed typology of parents or parenting style, as parents can have—and have had—many understandings of their children’s co-presence while working.

4.1 Cluster 1: the agentic child who enables or adapts to parental work

The first cluster comprises Position A (Autonomous) and Position B (Resilient): working in children’s co-presence was considered acceptable (see Fig. 1). In both positions, the acceptability was based on the agentic position of the child in relation to both work and the parent. However, the characterisation of the child varied.

In Position A (Autonomous), the child was characterised as an autonomous being with substantial knowledge and understanding of parental work. However, parents articulated two different outcomes of children’s autonomy for home-based work. First, children were seen as supportive and understanding. A home-based working mother (35–40 years old) of children aged 5 and 8 stated:

“The children do know, my children are very, how should I put it, they are totally understanding. So, they know that if we’re there together in the afternoon and someone calls and so on, that I’ll be on the phone or something. […] My children are very, how should I put it, they are totally sympathetic, yes.”

The quote illustrates that it was argued that children were able to anticipate why parents had to work and were thus respectful of parents’ needs when they worked. Children were portrayed as considerate of their working parents’ needs. In this sense, they facilitated their parents’ work activities.

Second, with Position A (Autonomous), it was argued that the child capitalised on their knowledge of their parents’ work for the child’s own benefit, as one home-based working father (35–40 years old) described his 4‑year-old child: “And [the child] often interrupts, of course, or just because of that, because [the child] sees that I somehow shut myself off a bit.” According to this line of argument, children were seen as deliberately interrupting in order to get their parents’ (full) attention and to stop them from working. By portraying the child as a source of disruption to their work, parents drew on opposing positions of work and family. However, by creating an autonomous child who was able to do and say what they needed and wanted, and to assert their interests even against the interests of their parents and their work, the parents were relieved of the risk of neglecting the child by working. It can be seen that both variations of Position A (Autonomous)—with a supportive or interrupting child—characterised parents’ home-based work as an acceptable arrangement which could not harm the co-present child.

In Position B (Resilient), the assumption that working in the co-presence of children was acceptable was based on children’s resilience. The parents constructed a child who could adapt to all circumstances and environments, including parents’ home-based work. The position was articulated by a home-based working mother (35–40 years old) of children aged 4 and 6 in the following way: “They [children] don’t know it any other way, and I don’t know it any other way, so it is kind of like that, and not everything has to be perfect.” Working in children’s co-presence was understood as a legitimate arrangement which all—children and parents—would get used to, even when not understood as “perfect”. This logic assumes that children can and must adapt, without considering parents’ adaptation of working conditions. In this way, the idea of childhood as a time of innocence and protection from the adult world was challenged. However, with the image of the resilient child, working in the co-presence of children, similarly to Position A (Autonomous), was not seen as neglecting the child, but as an arrangement that was in line with the child’s competencies.

With Position B (Resilient), children’s needs were not viewed as the sole and exclusive responsibility of parents; on the contrary, work was conceptualised as equally important. The same mother described later in the interview how she would create an undisturbed working situation: the child “gets some film on and gets a Nutella sandwich, completely unpedagogical [laugh], it doesn’t matter, yes”. This evaluation of working and handling children’s co-presence as not “perfect” and “unpedagogical” can be seen in relation to—and as a departure from—middle-class good parenting responsibilities to prioritise healthy eating or quality time with children (Dermott and Pomati 2016; Harman and Cappellini 2018).

Cluster 1 held an agentic child, but both positions attributed different intentions and competencies to the child in relation to parental work: knowledge and—deliberate lack of—understanding or adaptability. However, through the figure of the agentic child, both positions established an idea of working parenthood that did not necessarily endanger a good childhood.

4.2 Cluster 2: the child’s needs determining parental work

The second cluster consists of Position C (Unpredictable) and Position D (Developing). Both positions had a middle position in terms of the acceptability of working in the co-presence of children (see Fig. 1), which in this cluster was determined by the child’s needs and lack of competencies.

In Position C (Unpredictable), children were understood as individual beings, implying that their needs differed according to their mood, which determined whether and in what way working in their co-presence was acceptable. Thus, parents had to accept and adapt to the child, which was articulated as follows by a home-based working mother (40–45 years old) of a 5-year-old child:

“I have to say that [working in the presence of the children] sometimes works and sometimes does not. It really is the case that there are times when it works very well, when [the child] does some colouring or crafts or goes out into the garden in the meantime. Or then it doesn’t work. […] that depends on the day.”

This statement illustrates that children’s moods and behaviours were conceived as unpredictable and impossible for parents to anticipate or control. Thus, with Position C (Unpredictable), research participants argued that whether a child was easy or difficult was a matter of fortune rather than parental success or failure, as exemplified by the following quote from a home-based working mother (35–40 years old) of children aged 5 and 8: “Well, my children are simply very tolerant. I’m really incredibly lucky.” This notion is at odds with the conceptualisation of parenting that dominates contemporary public and, to a large extent, academic discourse, which holds parents responsible for their children’s (future) outcomes (Ostner et al. 2016; Vincent 2017).

However, with Position C (Unpredictable)—in contrast to Position B (Resilient)—it was argued that it was the parents who needed to adapt their work arrangements to the child’s mood and not vice versa. The response of the home-based working mother of the first quote to the child’s unpredictable behaviour was described by the child’s father (40–45 years old) as follows: “Then [she] says: ‘No, I’ll come with you [the child], let’s do something together now and tomorrow or in the afternoon or whatever would also be fine [to work]’”. This suggests that parents—especially mothers, as comparable articulations by or about fathers were missing from the data—were expected to limit or adapt their own (home-based work) needs to ensure that children’s needs were met. Central to Position C (Unpredictable) was that parental home-based work and the flexibility that came with it was seen as a resource rather than an obstacle, which enabled the parent to be more responsive to the needs of the child. For example, by being able to choose spending time together instead of working, as illustrated by the quote above.

Position D (Developing) opposed Position C (Unpredictable) by grounding children’s characterisation in their developmental stage that made them (temporarily) dependent on adults’ guidance and control. Working in children’s co-presence was assumed to be acceptable when it was age-appropriate. However, the core of the position was not to link the acceptance of working in co-presence to a specific age, but to the assumption that children would gradually develop certain competencies. The following statement by a home-based working father (35–40 years old) of children aged 2 and 4 illustrates the developmental perspective which was characteristic for Position C (Unpredictable):

“I think there will be a bit more of that, maybe, the working hours we do, while the children are here. That’s of course now, they’re still relatively small. So here and there, when things are going well, I get the idea that I could do something when they’re there, when they’re playing quietly in the sandpit in the garden. I could try this and that. I have the feeling that it might not be that long until that will be possible here and there, because they also keep themselves busy on their own.”

The quote illustrates that with Position D (Developing), the research participants asserted that the central competence that children needed to develop was the ability to occupy themselves. At the same time, the possibility of limiting the child’s co-presence during the parent’s work, for instance through extended attendance at childcare facilities when the child reached an older age, was not considered a relevant perspective. The ability to occupy oneself was therefore seen as a desirable way of reconciling parents’ work with children’s co-presence at home.

The developmental perspective also shaped how in Position D (Developing) children’s disruption of parental home-based work was perceived. The interruption of parental work was framed as a symptom of the child’s immaturity. Thus, children’s lack of self-control was viewed as the source of their interruption, as illustrated by the description of a 6-year-old child by a home-based working mother (30–35 years old): “[The child] can’t keep their mouth shut and has to keep saying something.” This is in contrast to Position A (Autonomous), where it was assumed that children were intentionally interrupting. However, in line with the developmental understanding, children of a certain age were expected to have the skills to keep themselves occupied during parental work, as another home-based working mother (35–40 years old) of a 6-year-old explained: “I say no, I have to do something for a moment; [the child] has to wait a little or occupy themselves. That’s no problem at all with [the child], they’re already 6 years old.” In Position D (Dependent), therefore, research participants argued that the older the children were, the more acceptable it was to work in their presence. Nevertheless, the age at which children were expected to demonstrate self-control appeared to vary, as the two quotes about the 6‑year-old children illustrate.

Parents, however, held a demanding position in Position D (Dependent): On the one hand, they were seen as responsible for guiding and training children. On the other hand, they had to adapt their expectations and home-based work activities to the developmental stage of the child—in a similar way as discussed in Position C (Unpredictable).

Cluster 2 contained a child defined by their needs and competencies to be developed. Both positions did not problematise the co-presence of the child but pointed to what the parents had to do in order to fulfil their responsibilities towards the child: providing an appropriate environment or guiding and controlling the child.

4.3 Cluster 3: the child as a parented child

The third cluster consists of Position E (Attached), in which children were characterised as dependent, and working in their co-presence was assumed to be unacceptable. In this position, the attestation of the unacceptability was based on the assumption that parents’ lack of attention due to their engagement in work activities would conflict with children’s basic need for parental attention.

The interviewed parents identified children’s lack of understanding of why parents were not attentive, despite their presence, as a source of interruptions, as the following statement of a home-based working father (35–40 years old) about his 2‑year-old child shows: “It’s natural that [the child] doesn’t understand that I’m there but that I’m not available. Of course, [the child] doesn’t respect that.” The statement illustrates that with Position E (Attached), parents concluded that the child’s interruption of work was conceived as a way children could express their discomfort when their need for parental attention was not met. The position was opposed to Position A (Autonomous), in which the interruption was viewed as targeted attention-seeking based on children’s understanding of parental work. With Position E (Attached), children were thus viewed as sensing rather than knowing actors, which constructed children as being in an immature status, as the argumentation in the statement also illustrates (“natural”). While this idea of immaturity echoes the developmental child in Position D (Developing), in Position (E), the need for attachment and attention and not the development of competencies is the child’s characteristic feature.

In Position E (Attached), the possibility of working in children’s co-presence was not generally ruled out, but the interviewed parents postulated specific conditions: children’s needs for attention had to be fulfilled, as two home-based working parents (both 35–40 years old) in a joint interview described their 4‑ and 6‑year-old children:

“Mother: It actually works better if they [children] just hang around and do their thing.

Father: And that they have the feeling that we’re there anyway.”

The statement illustrates that children’s needs for attention could be met when the children had the feeling that their parents were there, which could be met when parents offered physical closeness while working. So, working in children’s co-presence was acceptable as long as parents were in immediate physical proximity, e.g., next to the child.

In Position E (Attached), parental attention and closeness were conceptualised as basic needs of children, and it was parents’ central responsibility to fulfil these needs. Statements made by home-based working mothers, albeit on a more general level, mirrored this need for closeness, as illustrated by the following quote by a home-based working mother (45–50 years old) of a 6-year-old: “I really want to get something out of it [having a child], and what’s the point of having a child if you give them away, so to speak? And it’s also much easier when you work at home to still spend time with your child”. By working at home, the basic need for closeness could—under certain circumstances—be reconciled with work.

In Cluster 3, the child was constructed as dependent on their parents’ attention and closeness. Parents were thus expected to put the child’s basic needs first. However, home-based work was constructed as the way of working that allowed parents to meet this need and, additionally, mothers to be close to their child while at work.

4.4 Missing positions: child neglect and exclusive parenting

In the map in Fig. 1, some areas remain empty, which means that some of the (many possible) discursive positions were not articulated. By speculating about these missing positions, one can, on the one hand, get a better understanding of what meanings of childhood and (working) parenthood have been made explicit by the interviewed parents. On the other hand, one gets a deeper understanding of the specificity of the sample, i.e., parents who worked at home as a permanent arrangement and not just as a temporary or exceptional arrangement.

The two mapped-out missing positions in Fig. 1 indicate the margins of the issue, which echo the historical characterisation of the wild and evil child as well as the agentic and responsible child (Jenks 1996; Smith 2012) and child-rearing norms that assign parents the position of providing hard discipline or child-centred bonding (Ostner et al. 2016). The lack of these polarised images of the child and corresponding child-rearing practices underlines the heterogeneity of the positions articulated by the parents in the interviews. While parents clearly referred to some features of these images, they did not adhere to their clear-cut logics and thus made room for ambiguity by combining different aspects of these historically grounded images.

Missing Position 1 (acceptable to work in the co-presence of a dependent child) would indicate that parents would prioritise their work above the child’s needs. An understanding of the child as wild and evil, yet immature and thus dependent (Jenks 1996; Smith 2012), would legitimise such a priority of work over children. The parental neglect of children’s demands for attention could be legitimised by understanding it as a form of (necessary) discipline (Ostner et al. 2016). That this position is missing emphasises the importance of the child and their needs, which made work in the presence of children legitimate only if it did not neglect or harm the child. But one could also assume that this position was not articulated by the interviewed parents, as it might have contradicted dominant normative understandings of (middle-class) child-led parenting ideologies (Dermott and Pomati 2016; Hays 1998). Moreover, individuals who prioritise gainful employment over their children’s needs may be working outside the home and would therefore prefer full-time day care for their children, or they may not have children at all. In both cases, these individuals would not participate in this study.

Missing Position 2 (unacceptable to work in the co-presence of an independent child) would perceive parents as overprotective, as children would not need parents’ (constant) attention or care. This could indicate the construction of an agentic and responsible child (Smith 2012) matched with permanent child-centred bonding and parenting (Ostner et al. 2016). Regarding this missing position, one can assume that it was perceived as acceptable to work whenever children did not need their parents’ care or attention. This emphasises the importance of paid work for the interviewed parents and a disregard for exclusive or helicopter parenting. Moreover, Missing Position 2 highlights that ideas of a natural and innocent child seemed not to conflict with parental (home-based) work. This may reflect the specific characteristics of the sample that only included home-based working parents. Individuals who would prioritise child-centred parenting to such an extent may choose not to work at all and opt for full-time parenting.

5 Discussion & conclusion

In this paper, I have examined the ways in which parents construct the child and the corresponding parental responsibilities, and thereby legitimise their ways of dealing with the co-presence of children during the performance of paid work at home, through the analysis of 25 qualitative interviews with positional maps. The particular area of interest was the relations between work and family through home-based work. I approached this situation as an atypical one that may need more legitimation but also offers opportunities to make explicit and challenge taken-for-granted notions of work and family (see also Handley 2023; Seymour 2007).

The analytical focus contributes to an understanding of good childhood and working parenthood that goes beyond simple dualism by introducing a new dimension: home-based work. Parents’ construction of the child across five discursive positions was complex and ambiguous, as were the corresponding parental responsibilities. In all positions, the child was constructed as different from the adult, which legitimised the parent to place certain expectations on the child, on themselves, and on the child’s appropriate (self-) regulation. I grouped the positions into three clusters: In Cluster 1, an agentic child capable of changing (autonomous child) or adapting (resilient child) to circumstances was constructed. In this cluster, the figure of the agentic child ruled out the possibility that parental home-based work was in conflict with the needs of the child or a cause of child neglect. In Cluster 2, the child was defined by their behaviour and needs (individual child) or their development of competencies (developing child). Both positions pointed to the parent’s responsibility towards the child to provide an appropriate environment or to guide and control the child as a precondition for working at home. Cluster 3 was about an attached and immature child (attached child). In this cluster, parents were expected to prioritise the child’s basic need for parental closeness. However, home-based work was understood as a way of working that allowed parents to (better) meet this need. Speculating about two missing positions highlighted the importance of the child and their needs as well as the importance of paid work for the interviewed parents: neither child neglect nor exclusive parenting was included in the parents’ constructions. In sum, meeting the child’s needs and not harming the child through paid work emerged as common ground, while the parents’ commitment to paid work was not questioned. Conversely, home-based work was seen as a way for parents to meet both work and care demands, as the child could be at home and close to the parents despite the parents’ commitment to paid work.

The interviewed parents’ different ways of legitimising work in the co-presence of the child contained both destabilising and stabilising elements of dominant discourses about working parenthood and good childhood. On the one hand, the regular and legitimate presence of the child and the working parent challenged the image of paid work as a constraint on the child’s family time and, in particular, time at home (Harden et al. 2013; Zeiher 2005). However, the co-presence of parent and child during work implied physical proximity rather than quality time and thus did not correspond to middle-class ideals of a good childhood or intensive parenting, defined by full parental emotional or mental attention and a protective separation between work and family (Eldén and Anving 2022; Harden et al. 2013; Pimlott-Wilson 2012). Similar to what has been described for mothers working at home during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, removing the spatial distance between work and family broadened the understanding of how parenting can be done “in accordance with different situational contingencies, priorities, capabilities and preferences” (Handley 2023, p. 1011). On the other hand, parents’ understanding of home-based work as allowing (more) flexibility to meet children’s needs was in line with middle-class ideologies of family as time spent together (Daly 2001; Eldén and Anving 2022). In this respect, the findings echo what Alison Edgley (2021) describes as “maternal presenteeism”, i.e., mothers organising their work flexibly enough to be there for their children despite working full-time. Through home-based work, parents’ devotion to their child could coexist with their commitment to paid work, rather than being constructed as contradictory, limiting or competing with the child’s needs, as is commonly the case (Hays 1998; Schmidt et al. 2023; Wall 2013). Taken together, parents’ constructions of the child and related parental responsibilities both challenged and reinforced ideologies of a good childhood that were in conflict with working parenthood: by overcoming the assumption that a good childhood had to be separate from paid work or focused on quality time, while at the same time maintaining or even reinforcing notions of a home and family-centred childhood that could be facilitated by parental work in the home. In other words, notions of a good childhood and working parenthood were bridged through home-based work.

The presented perspective on work and family gains significance given the increasing flexibilisation of work and the digitalisation of daily life in general. Additionally, home-office days among employees, especially parents, have increased in popularity in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic (Bachmayer and Klotz 2021). Therefore, the likelihood of parents performing some of their paid work tasks in the co-presence of their children is increasing. Nevertheless, the study’s focus on a relatively homogeneous group of individuals and families, and a specific industry, has limitations. The study design reflects, therefore, a certain heteronormativity about what family entails and a lack of socioeconomic diversity. Hence, the conditions and contexts in which the research participants engaged in home-based work must be considered advantageous compared to other groups, business sectors, and regions, where there is less flexibility and liberty on the home-based workers’ side. Numerous studies have been conducted on working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings presented here are not fully comparable in that it might make a difference whether the framework conditions are (relatively) freely chosen or whether working from home is forced by circumstances such as a pandemic.

This list of limitations already suggests several directions in which further research could be oriented: more diverse family forms and home-based workers in different and also less advantaged sectors of the economy. Alongside a comprehensive comparison of children in different age groups, exploring children’s own perspectives on this issue is another direction that research should take.

Notes

To define creative industries, I have followed the definition of the Kreativwirtschaft Austria (2017, p. 3).

In the doctoral research project, further data was collected, including interviews with children and observations of daily family life. However, these are not included in this paper.

References

Bachmayer, Wolfgang, and Johannes Klotz. 2021. Homeoffice: Verberitung, Gestaltung, Meinungsbild und Zukunft. Wien: Bundesministerium für Arbeit.

Baierl, Andreas, and Markus Kaindl. 2021. Kinderbildung und -Betreuung. In 6. Österreichischer Familienbericht 2009–2019, ed. Bundeskanzleramt, 940–989. Wien: Bundeskanzleramt.

Bock-Schappelwein, Julia, Matthias Firgo, and Agnes Kügler. 2020. Digitalisierung in Österreich: Fortschritt und Home-Office-Potential. WIFO Monatsbericht 7:527–538.

Bühler-Niederberger, Doris. 2005. Die Macht der Unschuld. Das Kind als Chiffre. Wiesbaden: VS.

Chung, Heejung, and Mariska van der Horst. 2018. Women’s employment patterns after childbirth and the perceived access to and use of flexitime and teleworking. Human Relations 71(1):47–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717713828.

Cieraad, Irene. 2013. Children’s home life in the past and present. Home Cultures 10(3):213–226. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174213X13712175825511.

Clark, Sue Campbell. 2000. Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations 53(6):747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001.

Clarke, Adele E., Carrie E. Friese, and Rachel S. Washburn. 2018. Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn, 2nd edn., Los Angeles: SAGE.

Collins, Caitlyn. 2020. Who to blame and how to solve it: Mothers’ perceptions of work-family conflict across western policy regimes. Journal of Marriage and Family 82(3):849–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12643.

Daly, Kerry J. 2001. Deconstructing family time: From ideology to lived experience. Journal of Marriage and Family 63(2):283–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00283.x.

Dermott, Esther, and Marco Pomati. 2016. “Good” parenting practices: How important are poverty, education and time pressure? Sociology 50(1):125–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514560260.

Edgley, Alison. 2021. Maternal presenteeism: Theorizing the importance for working mothers of “being there” for their children beyond infancy. Gender, Work & Organization 28(3):1023–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12619.

Eichmann, Hubert. 2010. Erwerbszentrierte Lebensführung in der Wiener Kreativwirtschaft zwischen Kunstschaffen und Dienstleistung. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 35(2):72–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-010-0055-y.

Eldén, Sara, and Terese Anving. 2022. “Quality time” in nanny families: Local care loops and new inequalities in Sweden. In Care loops and mobilities in nordic, central, and eastern European welfare states, ed. Lena Näre, L. Lise Widding Isaksen, 85–107. Cham: Springer.

Elliott, Sinikka, Rachel Powell, and Joslyn Brenton. 2015. Being a good mom: Low-income, black single mothers negotiate intensive mothering. Journal of Family Issues 36(3):351–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13490279.

European Union. 2019. Culture statistics, 2019th edn., Luxembourg: Office of the European Union.

Foucault, Michel. 1981. Archäologie Des Wissens. Frankfurt a.M.: Surhkamp.

Galinsky, Ellen. 1999. Ask the children: What America’s children really think about working parents. New York: William Morrow.

Gatrell, Caroline J., Simon B. Burnett, Cary L. Cooper, and Paul Sparrow. 2013. Work–life balance and parenthood: A comparative review of definitions, equity and enrichment. International Journal of Management Reviews 15(3):300–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00341.x.

Gough, Katherine V. 2012. Home as workplace. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, ed. Susan J. Smith, 414–418. San Diego: Elsevier.

Handley, Karen Maria. 2023. Troubling gender norms on Mumsnet: Working from home and parenting during the UK’s first COVID lockdown. Gender, Work & Organization 30(3):999–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12926.

Harden, Jeni, Kathryn Backett-Milburn, Alice MacLean, Sarah Cunningham-Burley, and Lynn Jamieson. 2013. Home and away: Constructing family and childhood in the context of working parenthood. Children’s Geographies 11(3):298–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.812274.

Harman, Vicki, and Benedetta Cappellini. 2018. Boxed up? Lunchboxes and expansive mothering. Families, Relationships and Societies 7(3):467–481. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674317X15009937780962.

Hays, Sharon. 1998. The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hilbrecht, Margo, Susan M. Shaw, Laura C. Johnson, and Jean Andrey. 2008. “I’m home for the kids”: Contradictory implications for work–life balance of teleworking mothers. Gender, Work & Organization 15(5):454–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00413.x.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2001. The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Homberg, Michael, Laura Lükemann, and Anja-Kristin Abendroth. 2023. From “home work” to “home office work”? Perpetuating discourses and use patterns of tele(home)work since the 1970s: Historical and comparative social perspectives. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation 17:74–116. https://doi.org/10.13169/workorgalaboglob.17.1.0074.

Honig, Michael-Sebastian. 2016. Review: Children and their parents in childhood studies. In Parents in the spotlight: Parenting practices and support from a comparative perspective Journal of Family Research., ed. Tanja Betz, Michael-Sebastian Honig, and Ilona Ostner, 57–77. Leverkusen-Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Jenks, Chris. 1996. Childhood. London: Routledge.

Kolb, Bettina. 2008. Involving, sharing, analysing—potential of the participatory photo interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1155.

Kreativwirtschaft Austria. 2013. Fifth Austrian creative industries report. Short Version. Wien: Kreativwirtschaft Austria, Austrian Federal Economic Chamber.

Kreativwirtschaft Austria. 2017. Seventh Austrian creative industries report. Executive summary. Wien: Kreativwirtschaft Austria, Austrian Federal Economic Chamber.

Kreativwirtschaft Austria. 2023. Österreichischer Kreativwirtschaftsbericht 2023. Wien: Kreativwirtschaft Austria, Austrian Federal Economic Chamber.

Lee, Ellie, Jennie Bristow, Charlotte Faircloth, and Jan Macvarish. 2014. Parenting culture studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lott, Yvonne, and Anja-Kristin Abendroth. 2020. The non-use of telework in an ideal worker culture: Why women perceive more cultural barriers. Community, Work & Family 23(5):595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2020.1817726.

Messenger, Jon C., and Lutz Gschwind. 2016. Three generations of telework: New ICTs and the (r)evolution from home office to virtual office. New Technology, Work and Employment 31(3):195–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12073.

Mirchandani, Kiran. 2000. “The best of both worlds” and “cutting my own throat”: Contradictory images of home-based work. Qualitative Sociology 23(2):159–182. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005448415689.

Morgan, David H.J. 2011. Rethinking family practices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nippert-Eng, Christena. 1996. Calenders and keys: The classification of “home” and “work”. Sociological Forum 11(3):563. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02408393.

Ostner, Ilona, Tanja Betz, and Michael-Sebastian Honig. 2016. Introduction: Parenting practices and parenting support in recent debates and policies. In Parents in the spotlight: Parenting practices and support from a comparative perspective Journal of Family Research., 5–19. Leverkusen-Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Perry-Jenkins, Maureen, and Naomi Gerstel. 2020. Work and family in the second decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family 82(1):420–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12636.

Pimlott-Wilson, Helena. 2012. Work–life reconciliation: Including children in the conversation. Geoforum 43(5):916–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.05.005.

Pollmann-Schult, Matthias, and Jianghong Li. 2020. Introduction to the special issue “parental work and family/child well-being”. Journal of Family Research 32(2):177–191. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-422.

Reckwitz, Andreas. 2002. Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory 5(2):243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432.

Reckwitz, Andreas. 2016. Praktiken und Diskurse. In Kreativität und soziale Praxis, ed. Andreas Reckwitz, 49–66. Bielefeld: transcript.

Reckwitz, Andreas. 2021. Subjekt. Bielefeld: transcript.

Reimann, Mareike, Florian Schulz, Charlotte K. Marx, and Laura Lükemann. 2022. The family side of work–family conflict: A literature review of antecedents and consequences. Journal of Family Research 34(4):1010–1032. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-859.

Robinson, Kerry H. 2008. In the name of “childhood innocence”: A discursive exploration of the moral panic associated with childhood and sexuality. Cultural Studies Review 2:113–129.

Schier, Michaela, Tino Schlinzig, and Giulia Montanari. 2015. The logic of multi-local living arrangements: Methodological challenges and the potential of qualitative approaches. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 106(4):425–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12159.

Schmidt, Eva-Maria, Fabienne Décieux, Ulrike Zartler, and Christine Schnor. 2023. What makes a good mother? Two decades of research reflecting social norms of motherhood. Journal of Family Theory & Review 15(1):57–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12488.

Seymour, Julie. 2007. Treating the hotel like a home: The contribution of studying the single location home/workplace. Sociology 41(6):1097–1114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038507082317.

Seymour, Julie. 2010. On not going home at the end of the day: Spatialised discourses of family life in single location home/workplaces. In Geographies of children, youth and families: An international perspective, ed. Louise Holt, 108–120. London, New York: Routledge.

Smith, Karen. 2012. Producing governable subjects: Images of childhood old and new. Childhood 19(1):24–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211401434.

Sullivan, Cath, and Suzan Lewis. 2001. Home-based telework, gender, and the synchronization of work and family: Perspectives of teleworkers and their co-residents. Gender, Work & Organization 8(2):123–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00125.

Vincent, Carol. 2017. “The children have only got one education and you have to make sure it’s a good one”: Parenting and parent–school relations in a neoliberal age. Gender and Education 29(5):541–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1274387.

Voydanoff, Patricia. 2005. Toward a conceptualization of perceived work–family fit and balance: A demands and resources approach. Journal of Marriage & Family 67(4):822–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00178.x.

Wall, Glenda. 2013. “Putting family first”: Shifting discourses of motherhood and childhood in representations of mothers’ employment and child care. Women’s Studies International Forum 40:162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.07.006.

Witzel, Andreas. 2000. Das problemzentrierte Interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132.

Zeiher, Helga. 2005. Der Machtgewinn der Arbeitswelt über die Zeit der Kinder. In Kindheit soziologisch, ed. Heinz Hengst, Helga Zeiher, 201–226. Wiesbaden: VS.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the special issues, whose valuable comments and suggestions helped to improve this paper, and all the research participants for their openness to participate in the project and share their experiences.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J. Mikats declares that he/she has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikats, J. About the (un)acceptability of working in the presence of the child: parents’ constructions of the child and corresponding parental responsibilities. Österreich Z Soziol 49, 439–459 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-024-00574-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-024-00574-2

Keywords

- Work-family relations

- Construction of the child

- Working parenthood

- Childhood studies

- Situational analysis