Abstract

Longitudinal transition studies are central to youth research but face particular challenges owing to panel attrition. While adolescents can be easily reached through institutions, their lives change after they leave school. Consequently, keeping them in further panel waves becomes more difficult. This methodological paper explores factors that are related to different patterns of panel attrition. In addition to general factors of survey participation associated with socio-demographic variables, such as gender and social background, we also consider aspects related to the survey topic which could influence patterns of attrition, such as career choice, and the survey experience (i.e., the evaluation of the questionnaire in the first wave). We use data from a five-wave panel study with young people in Vienna. About 3000 respondents participated in the first survey wave during their last year in general-track secondary school (2017–2018 academic year), and they were then surveyed annually over the next four years (2019–2022). We find that a group of respondents remain continuously in the panel, while some drop out permanently at some point and others drop out temporarily but drop in again later. Based on logistic regression models, the results show that gender, migration background, parental occupational status, and school grades are related to patterns of attrition. The survey experience in the first wave is partly related to these factors. Our results can inform future studies regarding causes for and consequences of panel attrition.

Zusammenfassung

Längsschnittstudien zum Übergang von der Schule in den Beruf sind für die Jugendforschung von zentraler Bedeutung, stehen aber aufgrund der Ausfallwahrscheinlichkeit in den Panels vor besonderen Herausforderungen. Während Jugendliche über Institutionen einfacher erreicht werden können, ändert sich ihr Leben nach dem Verlassen der Schule. Folglich wird es schwieriger, sie für die Teilnahme an weiteren Panelwellen zu erreichen. In diesem methodologischen Beitrag werden Faktoren untersucht, die mit verschiedenen Mustern der Ausfallwahrscheinlichkeit zusammenhängen. Neben allgemeinen Faktoren für die Teilnahme an der Umfrage, die mit soziodemografischen Variablen wie Geschlecht und sozialen Hintergrund zusammenhängen, werden auch Aspekte berücksichtigt, die sich auf das Thema der Umfrage beziehen und die Ausfallmuster beeinflussen könnten, wie z. B. Berufswahl und die Erfahrungen mit der Umfrage (d. h. die Bewertung des Fragebogens in der ersten Welle). Wir verwenden Daten aus fünf Erhebungswellen einer Panelstudie mit jungen Menschen in Wien. Etwa 3000 Befragte nahmen an der ersten Erhebungswelle in ihrem letzten Jahr in der Neuen Mittelschule teil und wurden dann in den folgenden vier Jahren (2018–2022) jährlich befragt. Wir stellen fest, dass eine Gruppe von Befragten kontinuierlich im Panel verbleibt, während einige zu einem bestimmten Zeitpunkt dauerhaft ausscheiden und andere vorübergehend ausscheiden, aber später wieder einsteigen. Auf der Grundlage von logistischen Regressionsmodellen zeigen die Ergebnisse, dass Geschlecht, Migrationshintergrund, beruflicher Status der Eltern und Schulnoten mit den Ausfallmustern zusammenhängen. Sie stehen zum Teil mit der Bewertung der Umfrage in der ersten Welle in Beziehung. Unsere Ergebnisse können künftige Studien über die Ursachen und Folgen der Ausfallwahrscheinlichkeit aus Panelstudien informieren.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The school-to-work transition (STWT) is particularly relevant in research on the (re‑)production of social inequalities and in socio-political debate. In the past decade, a number of panel studies on the STWT have been conducted in several countries. Examples from German-speaking countries are the “German National Educational Panel Study” (NEPS) (Blossfeld and Roßbach 2019), the Swiss study “Transitions from Education to Employment” (TREE) (Scharenberg et al. 2014), or the study “Pathways to the Future” (Flecker et al. 2020, 2023). The latter study is the data source for this article. In general, panel studies involve surveying respondents repeatedly over time, which enables observing how their characteristics change or remain stable. However, two types of non-response threaten panel results: non-response in the first wave and the failure to locate, contact, or establish collaboration in successive waves (de Leeuw and Lugtig 2014). The latter type of non-response is known as panel mortality or panel attrition, and it can undermine the validity and power of a study with decreased and potentially biased sample size (Watson and Wooden 2009; Stöckinger et al. 2018; Cumming and Goldstein 2016). Generally, missingness (cross-sectional or longitudinal) is problematic for the quality of results when it is assumed to be systematic. In this case, results might be biased (Lugtig 2014), and the effect can increase over the course of a panel study (Ahern and Le Brocque 2005; Goodman and Blum 1996). As a long-term consequence, the sample might no longer be representative, or covariance changes and the outcomes of a related dependent variable might be biased because of participants with specific attributes (Ahern and Le Brocque 2005).

Such possibilities make the analysis of panel attrition and non-response even more important. It is vital to understand “the nature and predictors of non-response and attrition” (Durrant and Goldstein 2008, p. 2). With the current study, we aim to contribute to the literature examining attributes that influence panel attrition among adolescent school leavers (e.g., Mühlböck et al. 2018; Becker 2022). More specifically, we want to explain different patterns of panel attrition and analyse the predictive power of variables collected in the first wave for adolescents’ panel “behaviour” (i.e., who participates constantly, who drops out, or who participates alternately). We aim to conceptually distinguish between socio-demographic factors, substantive variables related to the content of the panel survey (here the STWT), and methodical aspects and their interrelation as predictors of panel attrition. The survey panel data of the Pathways to the Future project were collected from 2018 to 2022 in a population of young people who were attending the 8th grade of a Neue Mittelschule (NMS) in the city of Vienna in the 2017–2018 academic year. The project is a five-wave panel study on the STWT of young people from the age of 15 to 20 years. It should be noted that the NMS is the general track of lower secondary education in Austria and the 8th grade is the final school year before the transition to further education or vocational education and training. Young people in this transitional phase experience several changes in their life circumstances while having to make important educational and career decisions. Young people are thus particularly difficult to track through time (Mühlböck et al. 2018, p. 37), and overall, the changes in their life circumstances could negatively affect panel participation. If certain sub-samples are more likely to drop out of a panel, important information on critical groups that are of particular interest in social politics, such as young people facing difficulties in STWT, might be missed. Thus, it is worth exploring patterns and causes of attrition within this group further. To systematically address factors related to adolescents’ panel attrition, we provide an overview of the state of knowledge on panel attrition in the next section to further contextualize our research questions about young people.

2 Understanding of panel attrition

2.1 State of knowledge

Unit non-response and panel attrition are often assumed to have similar causes. Individuals who are more likely to refuse to participate in a survey are also more likely to drop out of a panel (Mühlböck et al. 2018). However, most research on factors of non-response are based on cross-sectional surveys (Groves and Couper 1998; Groves et al. 2002; Biemer 2001; Groves and Peytcheva 2008). On that basis, some conceptual frameworks for survey participation exist and identify key factors for non-response (Durrant and Goldstein 2008). Using Social Exchange Theory (Goyder 1987) or the Leverage Saliency Theory (Groves et al. 2000), survey methodologists try to explain survey participation based on multicausal and interacting factors such as survey topic, question difficulty, interview mode, sample selection, interviewer, survey climate, and household and individual characteristics (Guzy 2015). According to the theoretical framework, survey participation is part of a social exchange between the respondent and the researcher, and a recipient will respond to a questionnaire if the perceived social benefits are greater than the costs associated with responding.

It is reasonable to assume that certain social groups participate less in surveys. Empirically, ample evidence shows that men are less likely to respond to survey requests, and the same holds for people living in urban and/or deprived areas, younger people, lower educated people, and people with a lower social economic status or unstable employment patterns (Montaquila et al. 2007; Groves and Couper 1998; Goyder 1987; Hox et al. 2012; Ahern and Le Brocque 2005; Sakshaug et al. 2011; Hawkes and Plewis 2006; Stoop 2004; Watson and Wooden 2009; Nicoletti and Peracchi 2005; Behr et al. 2005; Lipps 2006; Groves 2006). Additionally, surveys are known to have a middle-class bias, which could especially manifest in panels (Rothenbühler and Voorpostel 2016).

For panel studies, patterns of attrition can be differentiated as permanent drop-outs (also called attrition) and as returning respondents or temporary drop-outs (Lugtig 2014; Voorpostel 2010; Behr et al. 2005; de Leeuw and Lugtig 2014). Some studies have also shown that drop-outs differ by time of attrition (Lugtig 2014). Based on information on participants who drop out from earlier waves, scholars can explore potential reasons for and patterns of attrition (Durrant and Goldstein 2008; Mühlböck et al. 2018). Previous research has demonstrated that attrition is related to age, socioeconomic status, health, social integration, cognitive ability, skills, schooling, and education (e.g., Ahern and Le Brocque 2005; Alderman et al. 2001; Burkam and Lee 2000; Levin et al. 2000; Russell 2002; Martin et al. 2021; Bianchi and Biffignandi 2019). Studies that have included controls for a migration background have generally found negative effects on response probabilities (Zinn and Gnambs 2022; Lipps 2006), partly because a higher burden owing to language is assumed to be present (Lugtig 2014; Lipps 2006). Further studies on panel participation of young people confirm the relevance of socio-demographic characteristics, and add that social origin is also important. Students with low-educated parents or parents of lower occupational status are more likely to drop out from the panel (e.g., Becker 2022; Zinn and Gnambs 2022).

However, no clear link exists between socio-demographic variables and attrition. The speculation is that these variables are associated with different learned behaviours and skills, accessibility, and survey burden, which are all relevant for panel participation (Lugtig 2014, p. 702; Earp et al. 2022). For example, gender might be relevant as women are assumed to be more conscientious and more committed (Uhrig 2008) and thus more likely to participate in general and to stay in the panel. However, there is weak evidence for this assumption (Becker 2017). Moreover, “higher educated (…) tend to have the highest cognitive and communicative skills” (Voorpostel 2010, p. 361), and they thus experience less survey burden and are more likely to continue participation in future waves (Martin et al. 2021). Moreover, sociopsychological variables such as personality traits are assumed to be closely linked to attrition (Lugtig 2014; Mühlböck et al. 2018; Satherley et al. 2015). For example, evidence shows that conscientiousness reasonably explains participation in surveys (Mühlböck et al. 2018; Satherley et al. 2015), while extroversion and neuroticism increase the probability for attrition (Satherley et al. 2015). However, the evidence is not definitive because some studies find a negative effect for extroversion on attrition (Richter et al. 2014) and only a minor influence of personality (Bianchi and Biffignandi 2019).

Research also suggests that the willingness to cooperate and the difficulty in answering a questionnaire are important factors that can influence participation in a longitudinal survey (Hoch 2013). Thus, survey experience and survey design/characteristics are correlated with panel attrition (Haunberger 2011; Watson and Wooden 2009; Stöckinger et al. 2018). In other words, the topic of the survey itself and the ease in answering survey questions might be important in motivating people to participate in the prospective panel waves. The topic saliency is thought to be relevant because people are likely to be more willing to (continuously) participate in a survey when they are interested in the topic (Groves et al. 2000). Panel members judge their interest in the topic not only on the basis of the introductory description of the content but also on their experiences in previous waves (Voorpostel 2010). This could (partially) explain the usually high refusals in wave 2, which is when participants have more information to judge their interest in the survey topic and their knowledge about it (Burton et al. 2006). Commitment to participate in the panel is directly correlated with the participants’ attitudes towards the panel (Stocké 2006; Rogelberg et al. 2001) and with the perceived value of their answer or “joy/burden” in answering (Lugtig 2014; de Leeuw and Lugtig 2014). Evidence shows that the evaluation of the questionnaire in one wave can be a good predictor for participation in the next wave (Lugtig 2014). Interviewer assessment of participants’ cooperativeness and their joy or burden in answering questions is therefore a good predictor for participation in future waves (Watson and Wooden 2009; Olsen 2005). Some researchers found negative effects of extreme response styles and item non-response on attrition rates (Lipps 2006; Voorpostel 2010; Loosveldt and Carton 2001; Earp et al. 2022; Stöckinger et al. 2018). The relative completion time also has an impact on attrition, with a long interview time being negatively associated with future participation (Lugtig 2014; Hoch 2013; Minderop and Weiß 2022). Item non-response on specific questions about social status and education can be predictors for continued participation because they indicate motivation and survey burden (Earp et al. 2022). Further, if a respondent finds the survey cognitively or emotionally stressful, panel commitment is reduced (Mühlböck et al. 2018; Stocké 2006; Lugtig 2014; Rogelberg et al. 2001; Yan and Curtin 2010), but this reduction may be temporary. A temporary drop-out can also be due to time pressure or life changes (change of job or school, illness, etc.) in a specific time period.

2.2 Research questions and the present study

To generate deeper insights about panel attrition of young people, we analyse patterns of panel attrition, that is, how predictors differ between the adolescents who stay in the panel, those who drop out early, those who drop out later, and those who show an irregular response behaviour. As we do not have information on the life circumstances of attritors, we cannot observe the individual reasons for attrition directly. However, based on information of all respondents in the first panel wave, we can assume that different predictors are related with panel attrition (Lugtig 2014). In line with the state of knowledge on panel attrition, we hypothesize three groups of predictors: (a) socio-demographic variables, (b) a content-related/survey-specific aspect, and (c) methodological or method-induced reasons. These are specified below for our study of young adults.

RQ1: Are socio-demographic variables, factors related to the survey content on participants’ transition, and survey experience in the first wave related to patterns of attrition?

We test the relevance of socio-demographic variables for panel attrition, focusing on gender, social background characteristics (including parental educational background and migration background), and the main language spoken. Based on assumptions about skills and survey burden described above, we expect that differing willingness to participate in a panel is related to these characteristics. In our study of young people from one educational track, social background characteristics such as parental education and parental occupational status are assumed to be related to these skills (Anger and Schnitzlein 2017).

The topics in our study were the educational and occupational orientation processes in the transitional period beginning with the end of compulsory schooling. We assume that participants with difficulties in the STWT are more likely to drop out because people tend to avoid the “burden” of reporting on disappointments (e.g., Falk and Thies 2022). Furthermore, we assume that as adolescents progress through the transition, they might drop out or return to the panel when or if their situation stabilizes. Although we do not have information on the progress of the transition for drop-outs, we know that school grades and educational aspirations are factors that predict whether transitions will be more or less successful (e.g., Holtmann et al. 2019; Nießen et al. 2022). Thus, aspiration levels and indicators for school performance in wave 1 could affect attrition. However, the formation of clear aspirations per se has been shown to be a decisive task in adolescence (Staff et al. 2010) that not every 15-year-old has managed. As a consequence, the survey topic might not (yet) be relevant to all respondents equally (Valls et al. 2022).

Moreover, we expect that the willingness to participate in a longitudinal survey is related to the survey experience and difficulty in answering a questionnaire in the first panel wave. We assume that a high level of item non-response is associated with a lower likelihood of participating again. We make use of information on item non-response in the above described variables of specific interest (no answer, do not know) as well as the extent of item non-response in the first survey wave.

RQ2: How do survey experience, factors related to survey topic on transition experience, and socio-demographic factors interrelate as predictors of panel attrition?

Importantly, the three groups of potential predictors are assumed to be interdependent. We know that the course of the STWT differs by socio-demographic variables, such as gender, social background, and migration background, as well as by school performance (e.g., Holtmann et al. 2019; Achatz et al. 2022). Adolescents with characteristics that are associated with the skills that influence panel participation are also more likely to be better students and to have higher aspirations (Astleithner et al. 2021; Nießen et al. 2022). In that sense, those characteristics are also likely to influence the evaluation of the survey and item non-response in the first wave. We examine the assumed interdependencies in a step-by-step development of the regression model.

3 Methods and data

The project Pathways to the Future is a longitudinal study on young peoples’ lives, educational and occupational orientation, and labour market opportunities, as well as the conceived or promised, desired or dreaded future of young people in Vienna. This five-year panel study uses a mixed-methods longitudinal design consisting of qualitative interviews and self-administered online surveys. After an initial interview during their last year of lower secondary education at the age of 14 or 15, the respondents are interviewed annually. In this article, we focus on data from five waves of the standardized online survey conducted from 2018 to 2022 (Wöhrer et al. 2023).

The population for the study were all adolescents attending their final year in the general track of lower secondary schools (NMS) in Vienna in the winter term 2017–2018. A multi-stage recruitment strategy via schools was used. All 117 NMS in Vienna were contacted, with a total of 351 classes and about 8000 students. The schools received information letters with the links and codes for the online survey as well as information sheets for the young people and consent forms for the parents, including consent to be re-contacted in future waves. The final number of participating schools was 96. Of these, 53 schools participated with all their graduating classes and 46 with parts of their graduating classes (Wöhrer et al. 2023).

In wave 1 (Flecker et al. 2018), participants were contacted through schools and the online survey was conducted in this institutional setting. From wave 2 onwards, the respondents were individually contacted through multiple channels (letter, email, text message by phone), using the contact details provided in wave 1, and invited to participate. Participants received individual codes and links to participate. Participants who revoked their consent were removed from the panel database and were not contacted again. At the end of each wave, all participating young people received a personalised thank you letter. Further, a lottery with conditional incentives including several monetary (e.g. vouchers) and non-monetary (e.g. headphones, instant photo cameras) incentives were provided. In sum, 2854 young people from 236 classes completed the survey in wave 1 (for further information see Wöhrer et al. 2023). Of these, 777 young people participated in wave 2 (Reinprecht et al. 2019), 683 in wave 3 (Mataloni et al. 2020), 674 in wave 4 (Flecker et al. 2021), and 451 in wave 5 (Flecker et al. 2022). The sample for the analysis consists of 2810 participants who reported minimum information on sociodemographic variables in wave 1.

4 Operationalisation and variables

4.1 Dependent variable: pattern of attrition

In our analysis, we examine patterns of panel attrition over the five waves of the survey. For this purpose, a categorical variable on attrition patterns was created as the dependent variable (see Table 1), following classifications used in previous research (Voorpostel 2010; Behr et al. 2005; Burkam and Lee 2000). We differentiate between “stayers” who responded in all five waves and “drop-outs” who were lost over time. We further distinguish among the drop-outs between “early drop-outs” who only participated in the first panel wave and “later drop-outs” who participated in more than one wave before ceasing to participate (Lugtig 2014). With this differentiation, we also take into account the change from the first survey in the school context to individual survey participation (Zinn et al. 2020). Finally, we also define the group of “drop-ins” who are respondents with an irregular participation pattern; such participants have also been referred to as being ever-out, nonmonotone, or lurkers in other studies (Burkam and Lee 2000; Lugtig 2014; Voorpostel 2010).

4.2 Predictors

All variables used as predictors in the multivariate analysis were collected in the first wave (2018). We briefly describe the variables and frequencies (Table 2).

4.2.1 Socio-demographic variables

Respondents were asked about their gender and were able to choose between “male”, “female”, “can’t or won’t assign me”, and “don’t want to answer”. For our analysis gender is binary coded, differentiating between young men and women. The number of cases in the other categories is too small for in-depth analyses.Footnote 1

Social background characteristics include parental education, parental occupational status, and the migration background.

Respondents were asked about the highest educational degree of the father and the mother and the occupation of the father and the mother. In the analysis, we used the highest parental level of education. For example, if the mother completed a university degree and the father completed compulsory school, the mother’s university degree was recorded. The variable differentiates between (1) high educational background (at least one parent with university degree), (2) intermediate educational background (at most high school degree or apprenticeship), and (3) low educational background (at most compulsory school or no compulsory education). Moreover, we used the highest occupational status of the parents. We categorized three broad groups of occupational skill levels based on the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO-88) as used in previous research (e.g., Maaz et al. 2009, p. 1): (1) parents with low occupational status (skilled and unskilled workersFootnote 2), (2) high occupational status (academic professions and upper-level professionals), and (3) executives and members of the military forces. Both variables, parental educational background and occupational status, include the category “missing value” for those adolescents who did not report any information about their parents (refusal or “don’t know”).

Migration background is based on survey questions on the country of birth of the respondent and their parents. The variable is coded as first-generation migration background if the respondent was not born in Austria and second-generation background if the respondent was born in Austria but the mother, father, or both were not born in Austria. We use further information on the main language spoken with the mother, the individual who has already been shown in previous research to be a relevant reference person (e.g., Eisner et al. 2019). This indicator differentiates between German and not German.

4.2.2 Factors related to survey content on respondents’ transition process

Educational aspirations were measured with the question “If you could choose, what would you most like to do after your current school?” The variable for educational aspirations differentiates between (1) high aspirations (university), (2) intermediate aspirations (high school degree or apprenticeship), (3) low aspirations (compulsory school at most). Additionally, we include the category “missing value”, if the respondents did not report any information about their educational aspirations (refusal or “don’t know”).

Respondents were asked to report their school grades in mathematics, German, and English from their final report card. The school performance of the adolescents is operationalized as the average grade in these three subjects and grouped as (1) good, (2) average, or (3) poor. In the category “missing value”, the respondents did not answer one of the questions about school grades (refusal or “don’t know”).

4.2.3 Survey experience in the first wave

To evaluate the questionnaire at the end of the survey in the first wave, the participants were asked to rate the questionnaire on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = very good to 5 = insufficient. The variable for survey experience differentiates between (1) very good or good and (2) average to insufficient. We again included a category for “missing value” if the respondents did not give any rating.

We also make use of the completion time of the questionnaire in the first wave, measured in minutes. The variable was centred for further analysis.

Item non-response was counted as the number of questions omitted by the participant in the first wave. The variable distinguishes between (1) no question omitted, (2) one or two questions omitted, (3) three to six questions omitted, and (4) seven or more questions omitted. Moreover, it should be mentioned here, that item non-response for specific questions (i.e., the “missing value” category across all model variables) is an indicator for poor survey experience in the first wave.

5 Analytical strategy

To compare the different attrition patterns according to their socio-demographic characteristics, factors related to survey content on respondents’ transition process, and the survey experience in the first wave, we employ regression models to analyse different types of non-response patterns. We estimated separate logistic regression models for stayers versus (1) early drop-outs, (2) later drop-outs, and (3) drop-ins. Stayers serve as the baseline because they represent the ideal case of panel participation (Lugtig 2014). The results of our logistic regression models (beta coefficients reported in Table A1, online appendixFootnote 3) are robust in comparison with a multinomial logistic regression model (Table A2, online appendix). We also tested multilevel models taking into account the nested structure of our data in the first wave (Table A3, online appendix). However, the model statistics do not indicate model improvement in the multilevel framework and results are very similar to the logistic regression model. We estimate three model variations. To answer the research questions, we examine a model including all socio-demographic variables, educational aspirations, school grades, and indicators for survey experience in the first wave. To examine the suggested interdependencies of the factors, we compare the results with more parsimonious models: model 2, which includes socio-demographic variables and content related variables only, and model 3, which includes socio-demographic variables only. Previous research has critically examined the importance of personality traits for panel attrition. However, our study only contains a scale on locus of control with four items according to the Internal-External Locus of Control Short Scale-4 (IE‑4) (Kovaleva et al. 2014) and no other items (e.g., for Big 5). The index variable for locus of control did not increase the explanatory power of the model and was not a significant factor. This might also be due to measurement problems in this item set.

We estimate average marginal effects (AMEs) that make findings comparable across different model specifications and facilitates the interpretation of the coefficients. In our approach, AMEs for our categorial variables can be interpreted as the difference in the probability of having a specific panel drop-out/drop-in pattern compared with stayers. As an example, the female respondents in our sample had a four percentage point reduced probability of dropping out of the panel early compared with male respondents.

6 Results

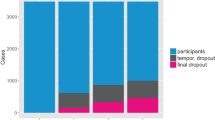

In our study, the majority of respondents in wave 1 were lost over time (Table 1). The largest group dropped out of the panel immediately after the first wave (60%). Another 16% dropped out after wave 2 or later, 15% showed irregular response behaviour, and 9% participated in all panel waves.

Table 3 presents the covariate AMEs of the three separate logistic regression models on panel attrition. We first focus on Model 1, which contains all assumed predictors of panel attrition. With regard to socio-demographic variables, female participants are less likely to drop out of the panel compared with male participants, which is in line with other studies. Moreover, we find differences between first-generation migrants and native Austrians as well as between second-generation migrants and native Austrians. Adolescents not born in Austria are more likely to drop out of the panel early. Furthermore, participants whose parents were not born in Austria are more likely to drop out of the panel early or late, but also to drop in again. Language spoken does not account for any further differences. Additionally, parents’ occupational status is a predictor of attrition patterns, while parental educational is not.Footnote 4 Adolescents whose parents have a high occupational status are significantly less likely to drop out of the panel early than adolescents whose parents have a low occupational status. We find a similar association between parental occupational status and later drop-out and drop-in with regard to the direction of the coefficient, but no significance at the 5% level.Footnote 5 The findings support the assumption that socio-demographic variables are important predictors of panel attrition among adolescents.

Furthermore, the survey-content-related predictors educational aspirations and school grades are associated with panel attrition. Young people with intermediate aspirations are more likely to drop out of the panel—as early drop-out, later drop-out, or drop-in. We see a similar association for the group of respondents with low educational aspirations. Adolescents with low educational aspirations are significantly more likely to drop out early. This outcome also means that adolescents with high educational aspirations are more likely to remain in the panel. These findings are in line with the assumed association between educational aspirations and panel attrition. We find no further evidence that not having (stated) aspirations also affects the probability of attrition. In line with the assumptions, school grades are significant predictors of panel drop-out. Adolescents with poor grades in the last year of lower secondary education are more likely to drop out of the panel, early or late, compared with respondents with good school grades. The young people who do not report school grades are also more likely to drop out. There are no differences by school grades with regard to the likelihood of staying in the panel versus dropping in.

The survey experience in the first wave is important for the likelihood of panel attrition. Respondents who rate the first wave of the survey poorly or do not provide a rating at all are more likely to drop out early. Interestingly, these groups are also more likely to drop in again. The rating of the first-wave questionnaire is a particularly strong predictor for the drop-in pattern. The completion time is not significant but item non-response in the first wave is an important predictor: The higher the number of unanswered questions in the first wave, the more likely respondents are to drop out early from the panel. The adolescents with a high number of unanswered questions in the first wave are also more likely to drop out late or to drop in again. The findings are in line with the general assumption that the survey experience in the first wave is a predictor for panel attrition. However, we find that survey experience in wave 1 is associated with early drop-out and later drop-out, as well as irregular response behaviour.

Finally, we analyse the relationship between the three conceptual groups of predictors. All three groups of variables contribute to the model quality in a relevant way, as confirmed in likelihood ratio tests for step-by-step modelling (Table 3). Detailed interrelations between the predictors can be determined from the comparison of the AMEs in Model 1 with the more parsimonious Models 2 and 3. When we do not control for survey experience in the first wave in Model 2, then the difference in the likelihood of dropping out of the panel (early or later) for young people with missing information on school grades compared with those with good school grades is stronger than in Model 1. Similarly, a stronger association can be observed in the category missing value for educational aspirations by comparing Model 2 and Model 1. The availability of information in the content variables on school grades and educational aspirations in wave 1 is partially coupled with the respondents’ general survey experience, which then also predicts future panel attrition. Beyond that there is little change in the AMEs of socio-demographic variables such as gender, migration background, and parental occupational status in Model 2 compared with Model 1, suggesting that these are not systematically related to the adolescents’ survey experience in wave 1. However, in the model with socio-demographic variables only (Model 3), the association between gender and panel attrition patterns and the association between parents’ occupational status and panel attrition patterns are somewhat stronger than in the other models. For gender, this association is true across all three comparisons, that is, stayers versus early drop-outs, later drop-outs, and drop-ins. Regarding the occupational status, the association between high parental status and the probability of early drop-out increases when school grades and educational aspirations are not controlled for. Thus, in line with our expectations, differences in patterns of panel attrition by gender and parental occupational status are partially related to the school grades and educational aspirations. Overall, AMEs of the socio-demographic variables and content variables on panel participation change only slightly across the step-by-step models. The interrelations between the conceptual variable groups are relatively weak. All three conceptual groups of predictors are relevant independently.

7 Conclusion

In this contribution, we examined how patterns of panel attrition in a longitudinal survey on the STWT depends on socio-demographic variables, survey-topic-related aspects, and survey experience of adolescents. To do so, we used data from a study on young people in the general track of secondary schools in Vienna who were surveyed for the first time in their final school year and then annually for a total of five waves (2018–2022). The study thus exemplifies a group of young people who are both of high political interest and difficult to reach in surveys. While most respondents in our study dropped out of the panel directly after the first wave, some respondents dropped out of the panel later and others dropped in again.

Our results confirm that socio-demographic variables, the content of the survey on participants’ transition process, and survey experience in the first wave are relevant predictors of panel attrition. In line with previous findings based on STWT panels, attrition was more likely for males, migrants, people from lower status parental backgrounds, and poor school grades (e.g., Becker 2022; Falk and Thies 2022; Zinn et al. 2020). We also find higher panel attrition among those with relatively low educational aspirations, and people who were not satisfied with the survey in the first wave. The findings clearly show that some groups of adolescents can be reached better than others in panel studies. This imbalance can have detrimental effects on panel estimates. However, not every tested variable was a significant predictor. Indeed, occupational status of parents was a significant predictor, but not their educational background; migration background was a predictor, but not the main language spoken at home; and the rating of the questionnaire and number of omitted questions in wave 1 were significant, but not the completion time.

Regarding the interrelation of variable groups as predictors of panel attrition, our results showed that socio-demographic, content-related, and survey-related predictors were largely independent. Few interdependencies were observable though: Differences in panel attrition by gender and parental occupational status were partly weaker when we controlled for educational aspirations and school grades. This outcome could indicate that women and adolescents from higher status families are better prepared for the STWT overall and thus find the survey more relevant/interesting and are happier talking about school and aspirations. In addition, missing values for the questions on aspiration and school grades were associated with survey experience in wave 1, which could indicate a sensitivity to these topics that leads to an overall more negative perception of the survey.

Beyond the predictors of panel attrition, the high drop-out rate in wave 2 could be due to the change in contact procedure and setting for conducting the survey: an institutional setting in schools in wave 1 versus individual contact and completion during leisure time from wave 2 onwards. Other studies on STWT have already shown that such a change is accompanied by increased panel attrition (e.g., Zinn et al. 2020). Participation rates were potentially boosted in wave 1, when it is easy to make students join a survey in the school context, and become problematic later on when it is challenging to keep them participating. Within a rational choice framework, it would make sense to assume that participation costs were higher from wave 2 onwards. Furthermore, commitment to the panel study might be more difficult to establish when baseline interviews include recruitment via an institution rather than through individualised (and thus potentially tailored and personal) approaches. However, we did not have any information on individual reasons for nonparticipation. Furthermore, higher participation rates did not necessarily coincide with higher data quality (Peytchev 2012; Davern 2013). It should also be noted that the third waveFootnote 6 of the survey was conducted during the first lockdowns due to the Covid-19 pandemic. We cannot determine the effects the lockdowns could have had on attrition patterns, but other research has shown that panel participation of young people increased in the lockdown (Becker et al. 2022).

Our study has limitations. We were unable to offer insights into mechanisms behind the predictors of panel attrition in our analysis. With regard to changing life situations in the STWT, it is impossible to include information about failure or success in implementing a predictor on aspirations because no such information is available for participants who drop out in future waves. We could only use information on educational aspirations and school grades in the first wave as well-known predictors of successful STWT. Moreover, young people who did not provide information on educational aspirations and school grades in wave 1 were more likely to drop out of the panel. This association could exist for various reasons. The study content may have been less interesting and relevant to young people with low aspirations and poor school grades, they may have been more likely to face problems in the STWT, or they may have had less free time to respond to survey requests when they started work compared with those who stayed in further education. The fact that the first wave was launched in the institutional school setting might also negatively affect these students more: The survey might have been associated with school, and they did not want reminders of it. As a fact, poorly performing adolescents are at risk of being lost in panels on the STWT. One possibility for future research to track pathways of all adolescents would be to match administrational data with our panel data. Regarding young people with missing information on aspirations and school grades, more research is needed because the reasons for refusal or the “don’t know” answer can differ substantially (e.g., “I cannot remember”, “I don’t want to remember”, “I don’t want to say”) and thus the impact on attrition patterns can vary. More qualitative methodological research on reasons for missing values could be insightful (Vogl 2012). In addition, we tested variables for locus of control as we expected them to be possible influencing predictors, as mentioned in the state of research. However, although we could not find effects on panel attrition patterns, we did find potential measurement problems in this item set. Another limitation of the study is the specificity of the surveyed population (i.e., school leavers from the general track of secondary school in Vienna). In the highly tracked Austrian school system, this group of adolescents faces relative disadvantages in the STWT compared with students from higher tracks. Hence, our findings cannot necessarily be generalised to all adolescents, especially if one assumes that the survey burden is higher for the group surveyed in our study. However, findings from studies on relatively privileged young people, such as university students, are unclear as to whether they exhibit similar factors influencing panel attrition or not (Falk and Thies 2022; Zinn et al. 2020).

The exploration of three conceptual groups of predictors for panel attrition is a contribution to the state of survey methodology. We showed the limitations of non-response or attrition analysis that is only based on socio-demographic variables. Our findings underline that the content of the survey is related to patterns of attrition, but content-related factors are mostly neglected in non-response analysis—partly because of limited data availability for non-socio-economic variables, partly because of ignorance. Furthermore, we showed how difficult transition research can be and who is particularly at risk of being missed in research on social inequality. It is important to design a good and attractive questionnaire that keeps the burden low for all respondents, beyond further patterns associated with sociodemographic factors.

Notes

In total, seven cases answered that they cannot or do not want to assign themselves and 33 gave no answer.

Due to low case numbers for unskilled workers, this category was combined with the category skilled workers.

Online Appendix available here: https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/o:1647374.

We have tested the independence of social background indicators. Differences by parental educational background are not overlaid by occupational status.

It is worth noting the missing value of 39.68% (1115 participants).

Survey period March 2020 until May 2020.

References

Achatz, Juliane, Kerstin Jahn, and Brigitte Schels. 2022. On the non-standard routes: Vocational training measures in the school-to-work transitions of lower-qualified youth in Germany. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 74(2):289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1760335.

Ahern, Kathy, and Robyne Le Brocque. 2005. Methodological issues in the effects of attrition: Simple solutions for social scientists. Field Methods 17(1):53–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X04271006.

Alderman, Harold, Jere Behrman, Susan Watkins, Hans-Peter Kohler, and John A. Maluccio. 2001. Attrition in longitudinal household survey data. Demographic Research 5:79–124. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2001.5.4.

Anger, Silke, and Daniel D. Schnitzlein. 2017. Cognitive skills, non-cognitive skills, and family background: Evidence from sibling correlations. Journal of Population Economics 30(2):591–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0625-9.

Astleithner, Franz, Susanne Vogl, and Michael Parzer. 2021. Zwischen Wunsch und Wirklichkeit: Zum Zusammenhang von sozialer Herkunft, Migration und Bildungsaspirationen. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 46:233–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-021-00442-3.

Becker, Rolf. 2017. Gender and survey participation an event history analysis of the gender effects of survey participation in a probability-based multi-wave panel study with a sequential mixed-mode design. Methods, data, analyses https://doi.org/10.12758/mda.2021.08.

Becker, Rolf. 2022. Short- and long-term effects of reminders on panellists’ survey participation in a probability-based panel study with a sequential mixed-mode design. Qual Quant https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01554-y.

Becker, Rolf, Sara Möser, Nora Moser, and David Glauser. 2022. Survey participation in the time of Corona. Survey Research Methods 16(1):61–74. https://doi.org/10.18148/SRM/2022.V16I1.7896.

Behr, Andreas, Egon Bellgardt, and Ulrich Rendtel. 2005. Extent and determinants of panel attrition in the European Community Household Panel. European Sociological Review 21(5):489–512. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci037.

Bianchi, Annamaria, and Silvia Biffignandi. 2019. Social indicators to explain response in longitudinal studies. Social Indicators Research 141(3):931–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1874-7.

Biemer, Paul P. 2001. Nonresponse bias and measurement bias in a comparison of face-to-face and telephone interviewing. Journal of Official Statistics 17(2):295–320.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, and Hans-Günther Roßbach. 2019. Education as a lifelong process. The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Burkam, David T., and Valerie E. Lee. 2000. Effects of monotone and nonmonotone attrition on parameter estimates in regression models with educational data: demographic effects on achievement, aspirations, and attitudes. The Journal of Human Resources 33(2):555–572.

Burton, Jonathan, Heather Laurie, and Peter Lynn. 2006. The long-term effectiveness of refusal conversion procedures on longitudinal surveys. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 169(3):459–478.

Cumming, Joy, and Harvey Goldstein. 2016. Handling attrition and non-response in longitudinal data with an application to a study of Australian youth. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 7(1):53–63. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v7i1.342.

Davern, Michael. 2013. Nonresponse rates are a problematic indicator of nonresponse bias in survey research. Health services research 48(3):905–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12070.

Durrant, Gabriele B., and Harvey Goldstein. 2008. Analysing the probability of attrition in a longitudinal survey. Working paper methodology M 10/08. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/161623/1/s3ri-workingpaper-M10-08.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Earp, Morgan, Robin Kaplan, and Daniell Toth. 2022. Modeling the relationship between proxy measures of respondent burden and survey response rates in a household panel survey. Journal of Official Statistics 38(4):1145–1175. https://doi.org/10.2478/jos-2022-0049.

Eisner, Nora L., Aja L. Murray, Manuel Eisner, and Denis Ribeaud. 2019. A practical guide to the analysis of non-response and attrition in longitudinal research using a real data example. International Journal of Behavioral Development 43(1):24–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418797004.

Falk, Susanne, and Theresa Thies. 2022. Non-response in student surveys: The example of international students in German higher education institutions. In Survey-Methoden in der Hochschulforschung, ed. Gesche Brandt, Susanne de Vogel, 425–452. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Flecker, Jörg, Susanne Vogl, and Franz Astleithner. 2018. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave1. Forschungsprojekt des Instituts für Soziologie, Universität Wien.

Flecker, Jörg, Veronika Wöhrer, and Irene Rieder (eds.). 2020. Wege in die Zukunft. Lebenssituationen Jugendlicher am Ender der Neuen Mittelschule. Göttingen: V&R Unipress.

Flecker, Jörg, Paul Malschinger, and Brigitte Schels. 2021. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave4. Forschungsprojekt des Instituts für Soziologie, Universität Wien.

Flecker, Jörg, Paul Malschinger, Brigitte Schels, and Ona Valls. 2022. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave5. Forschungsprojekt des Instituts für Soziologie, Universität Wien.

Flecker, Jörg, Brigitte Schels, and Veronika Wöhrer (eds.). 2023. Junge Menschen gehen ihren Weg. Längsschnittanalysen über Jugendliche nach der Neuen Mittelschule. Göttingen: V&R Unipress.

Goodman, Jodi S., and Terry C. Blum. 1996. Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management 22(4):627–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639602200405.

Goyder, John. 1987. The silent minority. Nonrespondents on sample surveys. Cambridge: Policy Press.

Groves, Robert M. 2006. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 70(5):646–675.

Groves, Robert M., and Mick P. Couper. 1998. Nonresponse in household interview surveys. New York: Wiley.

Groves, Robert M., and Emilia Peytcheva. 2008. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias. A meta-analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly 72(2):167–189.

Groves, Robert M., Eleanor Singer, and Amy Corning. 2000. Leverage-saliency theory of survey participation. Public Opinion Quarterly 64:299–308.

Groves, Robert M., Don A. Dillman, John L. Eltinge, and Roderick J.A. Little (eds.). 2002. Survey nonresponse. New York: Wiley.

Guzy, Nathalie. 2015. Nonresponse Bias in telefonischen Opferbefragungen. In Nonresponse Bias, ed. Jürgen Schupp, Christof Wolf, 161–207. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Haunberger, Sigrid. 2011. Teilnahmeverweigerung in Panelstudien. Wiesbaden: VS.

Hawkes, Denise, and Ian Plewis. 2006. Modelling non-response in the national child development study. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 169(3):479–491.

Hoch, Carolin. 2013. Die Determinanten der Panelmortalität: Eine Analyse am Beispiel des Nationalen Bildungspanels. NEPS working papers, Vol. 26

Holtmann, Anne C., Laura Menze, and Heike Solga. 2019. Schulabgänger und -abgängerinnen mit maximal Hauptschulabschluss. In Handbuch Bildungsarmut, ed. Gudrun Quenzel, Klaus Hurrelmann, 365–388. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Hox, Joop, Edith D. de Leeuw, and Hsuan-Tzu Chang. 2012. Nonresponse versus measurement error. Are reluctant respondents worth pursuing? Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 113(1):5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0759106311426987.

Kovaleva, Anastassiya, Constanze Beierlein, Christoph J. Kemper, and Beatrice Rammstedt. 2014. Internale-Externale-Kontrollüberzeugung‑4 (IE-4). Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen

de Leeuw, Edith D., and Peter Lugtig. 2014. Dropouts in longitudinal surveys. In Wiley statsref. Statistics reference online, ed. Narayanaswamy Balakrishnan, Theodore Colton, Brian Everitt, Walter Piegorsch, Fabrizio Ruggeri, and Jef Teugels, 1–6. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Levin, Bonnie E., Heather L. Katzen, Beth Klein, and Maria L. Llabre. 2000. Cognitive decline affects subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 22(5):580–586. https://doi.org/10.1076/1380-3395(200010)22:5;1-9;FT580.

Lipps, Oliver. 2006. Attrition in the Swiss household panel: wave 2 through wave 7. Working paper, Vol. 4_06

Loosveldt, Geert, and Ann Carton. 2001. An empirical test of a limited model for panel refusals. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 13(2):173–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/13.2.173.

Lugtig, Peter. 2014. Panel attrition. Separating stayers, fast attriters, gradual attriters, and lurkers. Sociological Methods & Research 43(4):699–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113520305.

Maaz, Kai, Ulrich Trautwein, Cornelia Gresch, Oliver Lüdtke, and Rainer Watermann. 2009. Intercoder-Reliabilität bei der Berufscodierung nach der ISCO-88 und Validität des sozioökonomischen Status. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 12(2):281–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-009-0068-0.

Martin, Silke, Clemens Lechner, Corinna Kleinert, and Beatrice Rammstedt. 2021. Literacy skills predict probability of refusal in follow-up wave: evidence from two longitudinal assessment surveys. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24(4):413–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1763715.

Mataloni, Barbara, Camoli Molina Xaca, and Christoph Reinprecht. 2020. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave3. Forschungsprojekt des Instituts für Soziologie, Universität Wien.

Minderop, Isabella, and Bernd Weiß. 2022. Now, later, or never? Using response-time patterns to predict panel attrition. International Journal of Social Research Methodology https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2022.2091259.

Montaquila, Jill M., J. Michael Brick, Mary C. Hagedorn, Courtney Kennedy, and Scott Keeter. 2007. Aspects of nonresponse bias in RDD telephone surveys. In Advances in telephone survey methodology, ed. James M. Lepkowski, Clyde Tucker, J.M. Brick, Edith D. de Leeuw, Lilli Japec, Paul J. Lavrakas, Michael W. Link, and Roberta L. Sangster, 561–586. Hoboken: Wiley.

Mühlböck, Monika, Nadia Steiber, and Bernhard Kittel. 2018. Reaching the unreachables: A panel survey among unemployed young adults in Austria and recommendations on how to decrease nonresponse and attrition. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 47(2):35–48.

Nicoletti, Cheti, and Franco Peracchi. 2005. Survey response and survey characteristics: microlevel evidence from the European Community Household Panel. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 168(4):763–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2005.00369.x.

Nießen, Désirée, Alexandra Wicht, Ingrid Schoon, and Clemens M. Lechner. 2022. “You can’t always get what you want”: Prevalence, magnitude, and predictors of the aspiration–attainment gap after the school-to-work transition. Contemporary Educational Psychology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102091.

Olsen, Randall J. 2005. The problem of respondent attrition: Survey methodology is key. Monthly Labor Review 128:63–70.

Peytchev, Andy. 2012. Consequences of survey nonresponse. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 645(1):88–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212461748.

Reinprecht, Christoph, Barbara Mataloni, and Camilo Molina Xaca. 2019. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave2. Forschungsprojekt des Instituts für Soziologie, Universität Wien.

Richter, David, John L. Körtner, and Denise Saßenroth. 2014. Personality has minor effects on panel attrition. Journal of Research in Personality 53:31–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.08.001.

Rogelberg, Steven G., Gwenith G. Fisher, Douglas C. Maynard, Milton D. Hakel, and Michael Horvath. 2001. Attitudes toward surveys: Development of a measure and its relationship to respondent behavior. Organizational Research Methods 4(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141001.

Rothenbühler, Martina, and Marieke Voorpostel. 2016. Attrition in the Swiss household panel: are vulnerable groups more affected than others? In Surveying human vulnerabilities across the life course, ed. Michel Oris, Caroline Roberts, Dominique Joye, and Michèle Ernst Stähli, 223–244. Cham: Springer.

Russell, Stephen T. 2002. Childhood developmental risk for teen childbearing in Britain. Journal of Research on Adolescence 12(3):305–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00035.

Sakshaug, Joseph W., Ting Yan, and Roger Tourangeau. 2011. Nonresponse error, measurement error, and mode of data collection. Tradeoffs in a multi-mode survey of sensitive and non-sensitive items. Public Opinion Quarterly 74(5):907–933. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfq057.

Satherley, Nicole, Petar Milojev, Lara M. Greaves, Huang Yanshu, Danny Osborne, Joseph Bulbulia, and Chris G. Sibley. 2015. Demographic and psychological predictors of panel attrition: evidence from the New Zealand attitudes and values study. PloS One 10(3):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121950.

Scharenberg, Katja, Melania Rudin, Barbara Müller, Thomas Meyer, and Sandra Hupka-Brunner. 2014. Ausbildungsverläufe von der obligatorischen Schule ins junge Erwachsenenalter. Die ersten zehn Jahre. Ergebnisübersicht der Schweizer Längsschnittstudie Teil 1. Basel. https://edudoc.ch/record/202416/files/Scharenberg_etal_2014_Synopsis_TREE_Results_Part-I_Education_ger.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Staff, Jeremy, Angel Harris, Ricardo Sabates, and Laine Briddell. 2010. Uncertainty in early occupational aspirations. Role exploration or aimlessness? Social Forces 89(2):659–683. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0088.

Stocké, Volker. 2006. Attitudes toward surveys, attitude accessibility and the effect on respondents’ susceptibility to nonresponse. Quality & Quantity 40(2):259–288.

Stöckinger, Corinna, Sara Kretschmer, and Corinna Kleinert. 2018. Panel attrition in NEPS starting cohort 6. A description of attrition processes in waves 2 to 7 with regard to nonresponse bias. NEPS survey paper 35. https://www.neps-data.de/Portals/0/Survey%20Papers/SP_XXXV.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Stoop, Ineke A.L. 2004. Surveying nonrespondents. Field Methods 16(1):23–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X03259479.

Uhrig, Noah S. 2008. The nature and causes of attrition in the British household panel study. ISER working paper series 5. https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/files/working-papers/iser/2008-05.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Valls, Ona, Franz Astleithner, Brigitte Schels, Susanne Vogl, and Raphaela Kogler. 2022. Educational and occupational aspirations: A longitudinal study of Vienna youth. Social Inclusion 10(2):226–239. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v10i2.5105.

Vogl, Susanne. 2012. Children between the age of 5 and 11. what “don’t know” answers tell us. Quality & quantity 46(4):993–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9438-9.

Voorpostel, Marieke. 2010. Attrition patterns in the Swiss household panel by demographic characteristics and social involvement. Swiss Journal of Sociology 36(2):359–377.

Watson, Nicole, and Mark Wooden. 2009. Identifying factors affecting longitudinal survey response. In Methodology of longitudinal surveys, ed. Peter Lynn, 157–181. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Wöhrer, Veronika, Susanne Vogl, Brigitte Schels, Paul Malschinger, Barbara Mataloni, and Franz Astleithner. 2023. Methodische Grundlagen und Forschungsdesign der Panelstudie. In Junge Menschen gehen ihren Weg. Längsschnittanalysen über Jugendliche nach der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Brigitte Schels, and Veronika Wöhrer, 29–56. Göttingen: V&R Unipress.

Yan, Ting, and Richard Curtin. 2010. The relation between unit nonresponse and item nonresponse. A response continuum perspective. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 22(4):535–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edq037.

Zinn, Sabine, and Timo Gnambs. 2022. Analyzing nonresponse in longitudinal surveys using Bayesian additive regression trees: a nonparametric event history analysis. Social Science Computer Review 40(3):678–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320928242.

Zinn, Sabine, Ariane Würbach, Hans W. Steinhauer, and Angelina Hammon. 2020. Attrition and selectivity of the NEPS starting cohorts: An overview of the past 8 years. AStA Wirtschafts- und Sozialstatistisches Archiv 14(2):163–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11943-020-00268-7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Sociology at the University of Vienna and the members of the steering committee of the Pathways to the Future project (PI Jörg Flecker). In addition, we would like to thank the editors, the two anonymous reviewers and the participants of the conference “JuBilA—Jugend, Bildung, Arbeit” of the section Sociology of Education (German Sociological Association) for their helpful comments.

Funding

This publication was supported by the Austrian National Bank (OeNB) under grant agreement number 18283 “When Dreams (Do Not) Come True” (PI Susanne Vogl). Additionally, the “Pathways to the Future” project was conducted in co-operation with and partly financially assisted by the University of Vienna (Department of Sociology), the Chamber of Labour Vienna, the Vienna Employment Promotion Fund (WAFF), the Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Research and the Federal Ministry for Labour and Economy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

P. Malschinger, S. Vogl and B. Schels declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online under https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/o:1647374 in the format provided by the authors (unedited).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malschinger, P., Vogl, S. & Schels, B. Drop in, drop out, or stay on: Patterns and predictors of panel attrition among young people. Österreich Z Soziol 48, 427–450 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00545-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00545-z