Abstract

Background

The ability to classify patients’ goals of care (GOC) from clinical documentation would facilitate serious illness communication quality improvement efforts and pragmatic measurement of goal-concordant care. Feasibility of this approach remains unknown.

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility of classifying patients’ GOC from clinical documentation in the electronic health record (EHR), describe the frequency and patterns of changes in patients’ goals over time, and identify barriers to reliable goal classification.

Design

Retrospective, mixed-methods chart review study.

Participants

Adults with high (50–74%) and very high (≥ 75%) 6-month mortality risk admitted to three urban hospitals.

Main Measures

Two physician coders independently reviewed EHR notes from 6 months before through 6 months after admission to identify documented GOC discussions and classify GOC. GOC were classified into one of four prespecified categories: (1) comfort-focused, (2) maintain or improve function, (3) life extension, or (4) unclear. Coder interrater reliability was assessed using kappa statistics. Barriers to classifying GOC were assessed using qualitative content analysis.

Key Results

Among 85 of 109 (78%) patients, 338 GOC discussions were documented. Inter-rater reliability was substantial (75% interrater agreement; Cohen’s kappa = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.60–0.73). Patients’ initial documented goal was most frequently “life extension” (N = 37, 44%), followed by “maintain or improve function” (N = 28, 33%), “unclear” (N = 17, 20%), and “comfort-focused” (N = 3, 4%). Among the 66 patients whose goals’ classification changed over time, most changed to “comfort-focused” goals (N = 49, 74%). Primary reasons for unclear goals were the observation of concurrently held or conditional goals, patient and family uncertainty, and limited documentation.

Conclusions

Clinical notes in the EHR can be used to reliably classify patients’ GOC into discrete, clinically germane categories. This work motivates future research to use natural language models to promote scalability of the approach in clinical care and serious illness research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Delivery of goal-concordant care—that is, medical care that aligns with and promotes patients’ goals and preferences regarding treatment intensity, functional outcomes, and longevity—is widely supported as the highest quality of care.1,2 Indeed, goal-concordant care has been identified as a key priority by the National Academy of Medicine and rated by an expert panel as the most important outcome measure for studies of advance care planning.3,4 In order to provide goal-concordant care, clinicians must engage patients or their surrogate decision-makers in goals-of-care (GOC) discussions to elicit their values, goals, and care preferences,5,6 and then document those conversations in the electronic health record (EHR) to optimally guide the future care they receive.1,7,8

Recent advances in natural language processing and machine learning methods have been applied to identify documented GOC discussions from clinical notes in the EHR to inform quality improvement initiatives and evaluate palliative care interventions.9,10,11 However, distinguishing among different goals within documented GOC discussions has proved a more challenging task.12 Prior studies have relied on more readily available, limited proxies for GOC such as code status or physician orders for life-sustaining treatments because they are more readily available,13,14,15,16 or focused on a disease-specific treatment preference thus limiting generalizability.17,18 Other studies have queried patients directly about their GOC,9,19,20 an approach that suffers from data missingness, failure to capture the dynamic nature of patients’ goals, and impracticality for large clinical trials. These limitations could potentially be mitigated by using clinical notes to classify patients’ GOC, but the feasibility and reliability of this approach is unknown.

Several frameworks exist for classifying GOC to enable the measurement of goal-concordant care.21,22,23 One framework for measuring goal-concordant care by co-author Halpern proposes using clinical notes in the EHR to classify GOC, which, if feasible, would enable a generalizable and pragmatic method that can be broadly applied in clinical research and clinical care. We thus performed a retrospective mixed-methods study to evaluate the feasibility of classifying patients’ GOC from clinical EHR notes among a cohort of patients hospitalized with serious illness. We also describe the frequency and patterns of changes in patients’ goals over time and identify barriers to reliable goal classification. Limited results from this study were reported in abstract.24,25

METHODS

Design

We conducted a retrospective chart review study among 120 randomly selected patients hospitalized between April 1, 2019, and July 31, 2019, at the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS). We employed an explanatory sequential (quantitative to qualitative) mixed-methods approach26 to identify possible mechanisms for challenges encountered in classifying goals and potential opportunities to refine the GOC classification framework. This study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the Institution Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Study Population and Setting

For this feasibility, mixed-methods study of a novel GOC classification method, we targeted an analytic sample size of 100 unique patient encounters. Eligible patient encounters included adults (≥ 18 years of age) admitted for ≥ 3 calendar days to one of three urban, academic-affiliated hospitals at UPHS. To achieve our primary study objective, we sought a patient sample enriched for documented GOC discussions while also avoiding introducing selection bias (as would occur with purposive sampling of charts based on the presence of a documented GOC discussion). Thus, we first restricted the eligible sample to patients with ≥ 50% risk of death within 6 months of admission, for whom there is expert consensus that a GOC discussion is recommended prior to hospital discharge.27 Six-month mortality risk was determined by an EHR-based mortality prediction model previously developed and validated in the study hospitals.28 To enable our secondary longitudinal assessment of patients’ GOC, patients must also have had at least one prior inpatient or outpatient encounter at UPHS within 12 months prior to the eligible admission. We then employed random sampling stratified evenly across high vs very high 6-month mortality risk (50–74% high and ≥ 75% very high) to identify 120 patient charts. After removing one duplicate patient chart, we piloted and refined the classification framework on 10 charts, with the remaining to be used as the final analytic sample.

Data Collection and Variable Definitions

Patient Characteristics

Patients’ self-reported sociodemographic data were obtained from the UPHS EHR clinical data warehouse: binary sex, race, ethnicity, religion, and primary language. Race, ethnicity, and primary language were analyzed as binary variables due to low numbers of subjects in minority categories. An inpatient palliative care consultation was identified by a signed consult order during the index hospital encounter. During the 6-month follow-up period, we collected all hospital readmissions, home care visits, and subsequent palliative care consultations.

Goals of Care

A GOC discussion was defined as a conversation between a clinician and a patient and/or patient’s surrogate decision-maker about the patient’s values or goals with respect to their preferences for medical care that was documented anywhere in an EHR clinical note.5,19 Isolated mentions of code status without an accompanying discussion of broader goals were not included.

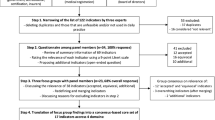

The study lead investigators (CA, AS, KC) applied an adapted framework for classifying goals of care from EHR data into five initially prespecified categories: “comfort-focused care,” “maintain or improve function,” “life extension,” “unclear,” and “making it to a life event.”5,21,29 We conducted initial consensus chart reviews on 10 randomly selected charts (5 high-risk mortality and 5 very-high-risk mortality) to identify GOC conversations and to refine GOC categories and definitions. Charts were reviewed both independently and as a team to build consensus through group discussion. This process resulted in a retention of four categories of GOC (Table 1), with a consolidation of “making it to a life event” into the broader category of “life extension” due to its very low prevalence. These charts were excluded from the final analytic sample and reserved for coder training on GOC identification and categorization.

GOC identification and categorization was then completed by six trained coders, all of whom were physicians-in-training (two fellows (CA, critical care; LH, palliative care) and four residents (AS, SY, AB; internal medicine; JH, cardiac surgery). Two coders independently reviewed all EHR notes spanning inpatient, ambulatory, and home care visits from 6 months prior to the index admission date through 6 months after and identified (1) a baseline GOC discussion, defined as the one preceding but most proximate to the index admission date or, if none, the first discussion after the index admission date, and (2) all subsequent GOC discussions from admission through death or 6 months (Fig. 1). We also recorded the EHR note type (e.g., history and physical, progress, advance care planning, consult note) in which the GOC discussion was documented. Disagreements in whether a note excerpt comprised a GOC discussion were resolved by consensus between coders.

Study follow-up and identification of goals-of-care (GOC) assessments over time based on presence or absence of GOC assessments at different time points. Panel A Patient record with documented GOC discussions in the 6 months prior to enrollment date and during follow-up. Panel B Patient record with no documented GOC in the 6 months prior to enrollment date but multiple GOC assessments during follow-up. Panel C Patient record with no documented GOC in the 6 months prior to enrollment date or during follow-up.

Once all GOC discussions were identified in the patient cohort, pairs of coders independently applied the adapted GOC framework to classify goals identified within each documented discussion into one of the four categories. Coders were blinded to each other’s classifications and coder pairs varied such that multiple combinations of coders were used, but all charts were reviewed by one of the fellows (CA, LH). GOC discussions for which there was true disagreement in goals classification between coders (i.e., not due to coder error) and those for which goals were classified as “unclear” were reviewed and adjudicated by two physicians with expertise in critical care and palliative care (CA (when not part of the coding pair) and KC).

Analyses

Statistical Analyses

We calculated the raw agreement percentage between coders for GOC classification and measured interrater reliability using Cohen’s kappa statistic. The primary unit of analysis was a GOC discussion. In secondary analyses, we explored patient-level changes in GOC over time and baseline characteristics associated with GOC documentation and a change in GOC in univariate analyses using Student’s t test, Pearson’s chi-square test, or Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon test as appropriate. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata v17 (College Station, TX), and significance was set at p < 0.05 for 2-tailed tests.

Qualitative Assessment

To identify sources of coder disagreement and ambiguity with the classification schema, we qualitatively assessed all GOC discussions for which (1) coders disagreed on the goal classification, or (2) the goal was classified as “unclear.” We systematically identified major themes from those data in three stages.30 First, one coder who was not involved in the initial GOC coding (LW) reviewed the foregoing GOC discussions using a process of open coding that included generating a list of codes as they emerged inductively from the data. All codes were then discussed by the study team, refined, and defined. Second, two coders (LW and AS) independently reviewed the GOC discussions and assigned applicable codes. Disagreements between coders were resolved by consensus. Finally, the team identified patterns across the codes and combined them into major themes.

RESULTS

Patient Cohort Characteristics

The cohort consisted of 109 unique patients (Supplemental Table 1) with a median age of 70 years (interquartile range (IQR) 63, 79). Fifty-three (49%) patients were female. Sixty-three patients (58%) identified as white and forty-one patients (38%) identified as Black. Most patients (n = 83, 76%) were insured by Medicare. Fifty patients (45%) had a diagnosis of metastatic cancer. The median Elixhauser comorbidity index was 6 (IQR 4,8), and the median 6-month mortality risk was 62% (IQR 55%, 66%) in the high-risk stratum, and 81% (IQR 78%, 87%) in the very-high-risk stratum. Eighty-five (78%) patients were admitted from the emergency department and 35 (32%) spent time in the ICU during the index hospitalization. Forty-three (39%) patients received a palliative care consultation during the index hospitalization. The median length of stay for the index hospitalization was 7.8 days (IQR 4.8, 12.0) and 16 (15%) patients died in the hospital. Among the 93 patients who survived the index hospitalization, 14 (15%) had a follow-up palliative care consultation after discharge, 61 (66%) were enrolled in home care, 54 (58%) had ≥ 1 readmission within 6 months, and 34 (37%) died during follow-up.

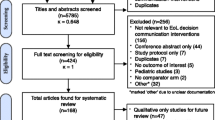

Documented Goals-of-Care Discussions

A total of 338 documented GOC discussions were identified among 85 of 109 (78%) patients (Fig. 2). Seventy-seven (71%) patients had > 1 documented GOC discussion during the study period (median 3 GOC discussions per patient [IQR 1, 5]). A baseline GOC discussion was documented in the 6 months prior to the index hospitalization for 49 of the 85 patients (45%). GOC discussions were documented within inpatient, ambulatory, and home care encounters and most commonly in advance care planning (ACP) notes (35%), followed by inpatient progress notes (25%) and inpatient consult notes (14%) (Supplemental Table 2). Among all 109 patients, those who died during the study period had more GOC discussions compared to those who survived (median 4 [IQR 3, 6] vs 1 [IQR 0, 3], p = < 0.001).

Categorization of Goals

Inter-rater reliability between coders for classifying GOC was substantial (75% inter-rater agreement; Cohen’s kappa = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.60–0.73). Inter-rater agreement was highest for goals classified as “comfort-focused” (90%) compared to “life extension” (74%), “maintain or improve function” (72%), and “unclear” (68%). Among the 57 goals initially classified as “unclear” by both coders, five (9%) were reclassified in the adjudication process. Overall, the most common GOC was “maintain or improve function” (N = 111, 33%), followed by “life extension” (N = 92, 27%), “comfort-focused” (N = 83, 25%), and “unclear” (N = 52, 15%) (Fig. 2). Excerpts of clinical text from GOC discussions representative of each goal type are provided in Table 1.

Trajectory of Goals of Care over Time

Among the 85 patients with at least one GOC discussion, the most common GOC at baseline was “life extension” (N = 37, 44%), followed by “maintain or improve function” (N = 28, 33%), “unclear” (N = 17, 20%), and “comfort-focused” (N = 3, 4%). Baseline GOC differed by patient sex (female: 29% life extension, 39% function, 7% comfort, 24% unclear vs male: 57% life extension, 27% function, 0% comfort, 16% unclear; p = 0 0.03)) and baseline predicted mortality (high risk: 34% life extension, 34% function, 0% comfort, 32% unclear vs very high risk: 51% life extension, 32% function, 6% comfort, 11% unclear; p = 0.04). Among the 77 (71%) patients with more than one GOC discussion, 66 (86%) had a different subsequent goal, which was most commonly comfort-focused (N = 49, 74%) (Fig. 3). Of the 17 (20%) patients whose initial goals were classified as unclear, 16 (94%) subsequently had a documented GOC discussion from which the goals were able to be classified into one of the other three categories (Fig. 4A). The only patient-level characteristic associated with an increased likelihood of changing GOC was having a diagnosis of metastatic cancer (100% vs 34%, p = 0.01). Among decedents with more than one documented GOC discussion (N = 49), 45 (92%) changed goals during the study period, with the majority (N = 42, 85%) expressing “comfort-focused” goals prior to death (Fig. 4B). The last documented GOC discussion occurred a median of 2.6 days prior to death (0.4, 10.5).

Tile plot showing frequency and classification of patients’ goals-of-care discussions over time. Made with R Core Team (2021). Ggplot. https://www.R-project.org/. Each patient is represented on the y-axis. Gray dashes denote individual goals-of-care discussions for each patient during the study period.

Alluvial flow diagrams illustrating changing distribution of goals of care (GOC) from baseline to final. Panel A All patients with ≥ 1 GOC discussion (N = 85). Last observation carried forward for 8 patients with only 1 GOC discussion. Panel B Decedent patients with ≥ 1 GOC discussion (N = 49). Last observation carried forward for 1 patient with only 1 GOC discussion. Made with SankeyMATIC (https://sankeymatic.com/build/).

Qualitative Analysis of Coder Disagreement and “Unclear” Goals

Of the 79 GOC discussions with initial inter-rater differences, 58 (73%) GOC discussions represented true coder disagreement requiring adjudication and were included in the qualitative assessment, along with the 52 (15%) GOC discussions classified as “unclear.” For the total 110 GOC discussions qualitatively reviewed, interrater agreement and reliability between coders were nearly perfect (95% interrater agreement; Cohen’s kappa = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.80–1.0). We identified three major themes: (1) multiple goals concurrently held or conditional; (2) explicit or implicit uncertainty; and (3) insufficient documentation (Table 2). Insufficient documentation was the most common theme among the 52 GOC discussions for which goals were classified as “unclear” (23, 44%), whereas multiple goals concurrently held or conditional was the most common theme among the 58 GOC discussions with true inter-rater disagreement (31, 53%).

DISCUSSION

In this mixed-methods study, we demonstrate that a review of EHRs can reliably classify GOC for most hospitalized patients at high risk of dying into three discrete and clinically relevant categories—life extension, maintain or improve function, and comfort-focused. Second, we find that the most common trajectory of GOC over time among such patients was from life extension to comfort-focused, particularly among the roughly one-third who died within 6 months of hospitalization. Third, our qualitative analyses reveal that ambiguity expressed by patients and families regarding their GOC and insufficient documentation are the main reasons why GOC cannot be discretely classified for a minority of patients, and why inter-rater reliability was imperfect.

This study provides proof-of-concept of a conceptual framework to identify patients’ individual GOC from unstructured clinical note data in the EHR. Prior studies using myriad methods have reported rates of documented GOC discussions ranging from 0 to 93% among patients with serious illness.9,31,32 Our findings likely represent an improvement from others for GOC detection (had we focused only on ACP notes, for example, we would have missed 65% of GOC conversations) and the 22% of patients with no identified GOC conversation are a reasonable estimate of a “true negative” for having had no GOC conversation. While there are undoubtedly instances in which high-quality GOC conversations occurred, if they were not documented within the EHR, that remains a problem for future care providers. These findings highlight how much work is still needed to increase the conduct and documentation of GOC conversations.

Moreover, we extended the measure beyond the typical binary outcome of the presence of a documented GOC discussion10,19,33 to further categorize patients’ goals from the documented discussions. This approach leverages contemporaneously documented GOC expressed by patients or surrogates during a serious illness conversation with their clinicians, thus avoiding the recall and desirability biases and data missingness that plague patient-reported GOC collected independent of real-world context.12,34 Importantly, this work suggests the potential for scalability by training text-based classification tools (e.g., natural language processing and machine learning methods) on reliable labels provided by clinicians-in-training, with only a minority requiring content expert review. If so, this would address a major challenge to serious illness research—the absence of a pragmatic, reliable, and patient-centered measure of goal-concordant care.

Indeed, although we find that goals are unclear in approximately 1 in 7 GOC discussions, our qualitative findings suggest that this classification is often a “true negative”—i.e., the categorization of these goals as unclear captured the real uncertainty that many patients and families experience in serious illness decision-making, the potential for multiple goals to co-exist, and the logical conditionality of some patients’ goals (e.g., if function cannot improve or be maintained, then focus on comfort). Further, the majority of patients with initially unclear goals had a subsequently documented GOC discussion in which goals were clarified, reflecting the important role of time in providing clarity35 and the longitudinal nature of high-quality communication in serious illness. Limited documentation by clinicians also contributed to coders’ uncertainty in definitively classifying patients’ goals, which could be addressed by designing EHR note templates that prompt more informative documentation of GOC discussions. Future iterations of a GOC categorization framework should disaggregate goals that are truly unclear from those with inferior documentation.

We observed a clear pattern of goals shifting toward comfort-focused care during the 12-month follow-up. This may represent the natural history of GOC among a cohort of patients with a limited prognosis. However, it also likely reflects clinicians’ tendencies to preferentially revisit GOC discussions when patients experience disease progression or a complication,36,37 particularly when goals are initially unclear or focused on longevity. This is supported by our finding that decedents were more likely to have > 1 GOC discussion, and most had new comfort-focused goals documented within days prior to death. More work is needed to validate and extend our exploratory findings of GOC trajectories in a prospective cohort to identify opportunities to improve the patient-centeredness of approaches to recurrent GOC discussions.38

Strengths of this study include a broadly defined population of seriously ill hospitalized adults that promotes the generalizability of this promising method for classifying GOC. The four classifications of GOC are sufficiently broad to allow for the categorization of heterogeneous goals across individuals, while still representing distinct and common approaches to care delivery in serious illness. We used a comprehensive definition to identify GOC discussions in clinical notes as was done in prior studies,5,19 but improved the method’s patient-centeredness by excluding isolated mentions of code status or a single treatment preference (e.g., radiation) that lacked any additional context of patients’ goals, values, or overall care preferences. Finally, our comprehensive chart review resulted in a more inclusive and generalizable sample of documented GOC discussions compared to relying on EHR note types or templates specific to GOC discussions.

The study must also be considered in light of several limitations. First, our study was limited to GOC documentation within the EHR at a single health system. We cannot comment on GOC documented in external health care systems during the study period. The culture and practice of GOC communication and documentation may differ across hospitals and health systems, which could impact the generalizability of the goals classification framework evaluated in this study. Moreover, while 38% of our study population identified as Black, we had low rates of representation of individuals from other racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. External validation in another health care system and among a more diverse cohort of patients is necessary. Second, documented GOC discussions are infused with clinicians’ interpretation and summary of the goals patients or their surrogates express (though the EHR is the primary means by which such medical information is communicated between clinicians). Relatedly, this method does not capture the uniqueness of individual patients’ goals (for example, to live long enough to make it to a family member’s wedding or to be sufficiently functional to care for or entertain grandchildren). A prospective validation study would allow for contemporaneous corroboration of patients’ GOC classification with the gold standard of patient- or surrogate-reported goals. Third, we focused on hospitalized patients with a limited prognosis based on expert recommendations regarding timely GOC discussions and to ensure a sufficient sample of documented GOC discussions to review. This study design choice undoubtedly influenced the epidemiology of the GOC discussions we report. For example, we may underestimate the proportion of patients at high mortality risk with comfort-focused goals at baseline because avoiding hospitalization is commonly desired by such patients. Similarly, a less sick cohort would likely have revealed fewer GOC discussions per patient. Fourth, while 110 GOC (33% of the total sample) were re-reviewed through the adjudication process and qualitative assessment of unclear goals, we did not re-review the 228 goals that had clear and concordant classification. As such, we cannot be certain that coder drift did not occur. Finally, any efforts to operationalize categorizing GOC at scale will need to advance automated techniques as the current approach of dual-chart review is resource-intensive.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, classifying seriously ill patients’ goals into distinct and clinically relevant categories using GOC discussions documented in the EHR is feasible. This GOC classification framework enhances the patient-centeredness of documented GOC discussion as an outcome measure, applies across different serious illnesses and throughout the duration of disease, and advances the much-needed development of a pragmatic approach to measuring goal-concordant care. Future work is needed to externally validate, optimize, and ideally automate this approach.

Data Availability

Deidentified participant data can be made available to researchers after publication and with approval of a methodologically sound proposal (catherine.auriemma@pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

References

Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAINTERNMED.2014.5271.

Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, Lupu D, Norton SA, McMillan SC, Herr K, Rotella JD, Casarett DJ. Measuring what matters: top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(4):773-781. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2015.01.012.

Dzau VJ, McClellan MB, McGinnis JM, et al. Vital Directions for Health and Health Care: Priorities From a National Academy of Medicine Initiative. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1461-1470. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.1964.

Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, Rietjens JAC, Korfage IJ, Ritchie CS, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ, Lorenz K, Howard M, Green MJ, Simon JE, Feuz MA, You JJ. Outcomes That Define Successful Advance Care Planning: A Delphi Panel Consensus. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):245-255.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.025.

Secunda K, Wirpsa MJ, Neely KJ, Szmuilowicz E, Wood GJ, Panozzo E, McGrath J, Levenson A, Peterson J, Gordon EJ, Kruser JM. Use and Meaning of “Goals of Care” in the Healthcare Literature: a Systematic Review and Qualitative Discourse Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1559-1566. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11606-019-05446-0.

Edmonds KP, Ajayi TA. Do We Know What We Mean? An Examination of the Use of the Phrase “Goals of Care” in the Literature. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(12):1546-1552. https://doi.org/10.1089/JPM.2019.0059.

Lamas D, Panariello N, Henrich N, et al. Advance Care Planning Documentation in Electronic Health Records: Current Challenges and Recommendations for Change. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):522–528. https://doi.org/10.1089/JPM.2017.0451.

Curtis JR, Sathitratanacheewin S, Starks H, Lee RY, Kross EK, Downey L, Sibley J, Lober W, Loggers ET, Fausto JA, Lindvall C, Engelberg RA. Using Electronic Health Records for Quality Measurement and Accountability in Care of the Seriously Ill: Opportunities and Challenges. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S52-S60. https://doi.org/10.1089/JPM.2017.0542.

Lee RY, Brumback LC, Lober WB, Sibley J, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Kross EK, Loggers ET, Fausto JA, Lindvall C, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Identifying Goals of Care Conversations in the Electronic Health Record Using Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):136-142.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2020.08.024.

Chan A, Chien I, Moseley E, Salman S, Kaminer Bourland S, Lamas D, Walling AM, Tulsky JA, Lindvall C. Deep learning algorithms to identify documentation of serious illness conversations during intensive care unit admissions. 2018;33(2):187-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318810421.

Avati A, Jung K, Harman S, Downing L, Ng A, Shah NH. Improving palliative care with deep learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(4):55-64. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12911-018-0677-8/TABLES/5.

Ernecoff NC, Mph KLW, Bennett A V, Hanson LC, Bennett A V, Hanson LC. Measuring Goal-Concordant Care in Palliative Care Research. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(3):e305-e314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.030

Kim YS, Escobar GJ, Halpern SD, Greene JD, Kipnis P, Liu V, Author C. The Natural History of Code Status Changes and Its Implications on Inpatient Mortality in Younger and Older Hospitalized Patients HHS Public Access. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(5):981-989. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14048.

Hopping-Winn J, Mullin J, March L, Caughey M, Stern M, Jarvie J. The Progression of End-of-Life Wishes and Concordance with End-of-Life Care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):541-545. https://doi.org/10.1089/JPM.2017.0317.

Jabbarian LJ, Maciejewski RC, Maciejewski PK, Rietjens JAC, Korfage IJ, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Prigerson HG. The Stability of Treatment Preferences Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(6):1071-1079.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2019.01.016.

Rahman AN, Bressette M, Enguidanos S. Quality of Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Forms Completed in Nursing Homes. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(5):538. https://doi.org/10.1089/JPM.2016.0280.

Knoepke CE, Chaussee EL, Matlock DD, Thompson JS, McIlvennan CK, Ambardekar AV, Schaffer EM, Khazanie P, Scherer L, Arnold RM, Allen LA. Changes over Time in Patient Stated Values and Treatment Preferences Regarding Aggressive Therapies: Insights from the DECIDE-LVAD Trial. Med Dec Making. 2022;42(3):404-414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X211028234/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0272989X211028234-FIG2.JPEG.

Parks Taylor S, Kowalkowski MA, Courtright KR, Burke HL, Patel S, Hicks S, Hurley C, Mitchell S, Halpern SD. Deficits in Identification of Goals and Goal-Concordant Care After Sepsis Hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(11). https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3714.

Lee RY, Kross EK, Torrence J, Li KS, Sibley J, Cohen T, Lober WB, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Assessment of Natural Language Processing of Electronic Health Records to Measure Goals-of-Care Discussions as a Clinical Trial Outcome. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231204. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2023.1204.

Modes ME, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Nielsen EL, Curtis JR, Kross EK. Did a goals-of-care discussion happen? Differences in the occurrence of goals-of-care discussions as reported by patients, clinicians, and in the electronic health record. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(2):251. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2018.10.507.

Halpern SD. Goal-concordant care — Searching for the Holy Grail. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1603-1606. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1908153.

Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving Goal-Concordant Care: A Conceptual Model and Approach to Measuring Serious Illness Communication and Its Impact. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S17-S27. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0459.

Turnbull AE, Hartog CS. Goal-concordant care in the ICU: a conceptual framework for future research. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1847-1849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4873-2.

Auriemma CL, Song A, Han J, Bain A, Walsh L, Halpern SD, Courtright KR. Longitudinal classification and trajectories of documented goals of care among hospitalized patients with serious illness. American Thoracic Society International Meeting, San Francisco. 2022;205(A3505).

Song A, Auriemma C, Han J, Haines L, Bain A, Walsh L, Halpern S, Courtright K. Longitudinal classification and trajectories of documented goals of care among hospitalized patients with serious illness. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, State of the Science Meeting. 2022.

Curry LA, Krumholz HM, O’Cathain A, Clark VLP, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. Mixed Methods in Biomedical and Health Services Research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967885.

Mohan D, Sacks OA, O’Malley J, Rudolph M, Bynum J, Murphy M, Barnato AE. A New Standard for Advance Care Planning (ACP) Conversations in the Hospital: Results from a Delphi Panel. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(1):69-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06150-0.

Courtright KR, Chivers C, Becker M, Regli SH, Pepper LC, Draugelis ME, O’Connor NR. Electronic Health Record Mortality Prediction Model for Targeted Palliative Care Among Hospitalized Medical Patients: a Pilot Quasi-experimental Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1841-1847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05169-2.

Kaldjian LC, Curtis AE, Shinkunas LA, Cannon KT. Goals of care toward the end of life: a structured literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(6):501-511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909108328256.

Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1089059/. Accessed 13 April 2023.

Uyeda AM, Lee RY, Pollack LR, Paul SR, Downey L, Brumback LC, Engelberg RA, Sibley J, Lober WB, Cohen T, Torrence J, Kross EK, Curtis JR. Predictors of Documented Goals-of-Care Discussion for Hospitalized Patients With Chronic Illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2022.11.012.

Perera N, Gold M, O’Driscoll L, Katz NT. Goals of Care Discussions Over the Course of a Patient’s End of Life Admission: A Retrospective Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39(6):652-658. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211035322.

Lee RY, Kross EK, Downey L, Paul SR, Heywood J, Nielsen EL, Okimoto K, Brumback LC, Merel SE, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Efficacy of a Communication-Priming Intervention on Documented Goals-of-Care Discussions in Hospitalized Patients With Serious Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4). https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2022.5088.

Comer AR, Hickman SE, Slaven JE, Monahan PO, Sachs GA, Wocial LD, Burke ES, Torke AM. Assessment of Discordance Between Surrogate Care Goals and Medical Treatment Provided to Older Adults With Serious Illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e205179-e205179. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.5179.

Song A. The Other Side. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1135-1136. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2020.2054.

Hauschildt KE. Whose Good Death? Valuation and Standardization as Mechanisms of Inequality in Hospitals. J Health Soc Behav. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465221143088.

Tranberg M, Jacobsen J, Fürst CJ, Engellau J, Schelin MEC. Patterns of Communication About Serious Illness in the Years, Months, and Days before Death. Palliat Med Rep. 2022;3(1):116-122. https://doi.org/10.1089/PMR.2022.0024.

Childers JW, White DB, Arnold R. “Has Anything Changed Since Then?”: A Framework to Incorporate Prior Goals-of-Care Conversations Into Decision-Making for Acutely Ill Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(4):864-869. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2020.10.030.

Acknowledgements:

The authors had full independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Pennsylvania or the National Institutes of Health. Limited results from this study were reported in abstract at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine State of the Science in February 2022 and the American Thoracic Society International Meeting in May 2022.

Funding

Dr. Auriemma is supported by a National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grant (K23-HL163402) and a National Institute of Health Loan Repayment Program Award (L30HL154185). Dr. Halpern is supported by an NHLBI Grant (2K24 HL143289). Dr. Courtright is supported by an NHLBI Grant (K23-HL143181).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Auriemma, C.L., Song, A., Walsh, L. et al. Classification of Documented Goals of Care Among Hospitalized Patients with High Mortality Risk: a Mixed-Methods Feasibility Study. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08773-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08773-z