Abstract

Background

Heart failure is a leading cause of death in the USA, contributing to high expenditures near the end of life. Evidence remains lacking on whether billed advance care planning changes patterns of end-of-life healthcare utilization among patients with heart failure. Large-scale claims evaluation assessing billed advance care planning and end-of-life hospitalizations among patients with heart failure can fill evidence gaps to inform health policy and clinical practice.

Objective

Assess the association between billed advance care planning delivered and Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure upon the type and quantity of healthcare utilization in the last 30 days of life.

Design

This retrospective cross-sectional cohort study used Medicare fee-for-service claims from 2016 to 2020.

Participants

A total of 48,466 deceased patients diagnosed with heart failure on Medicare.

Main Measures

Billed advance care planning services between the last 12 months and last 30 days of life will serve as the exposure. The outcomes are end-of-life healthcare utilization and total expenditure in inpatient, outpatient, hospice, skilled nursing facility, and home healthcare services.

Key Results

In the final cohort of 48,466 patients (median [IQR] age, 83 [76–89] years; 24,838 [51.2%] women; median [IQR] Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 4 [2–5]), 4406 patients had an advance care planning encounter. Total end-of-life expenditure among patients with billed advance care planning encounters was 19% lower (95% CI, 0.77–0.84) compared to patients without. Patients with billed advance care planning encounters had 2.65 times higher odds (95% CI, 2.47–2.83) of end-of-life outpatient utilization with a 33% higher expected total outpatient expenditure (95% CI, 1.24–1.42) compared with patients without a billed advance care planning encounter.

Conclusions

Billed advance care planning delivery to individuals with heart failure occurs infrequently. Prioritizing billed advance care planning delivery to these individuals may reduce total end-of-life expenditures and end-of-life inpatient expenditures through promoting use of outpatient end-of-life services, including home healthcare and hospice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of advance care planning (ACP) billing codes in 2016, policies increasingly tie their use to healthcare quality measures in value-based payment models.1,2 Since the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established billing mechanisms for ACP services to the Physician Fee Schedule under Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 99,497 and 99,498, ACP billing has increased each year preferences for future medical care in preparation for severe illness affecting the ability to communicate or make decisions.3,4,5 These ACP billing codes reimburse for time-based physician or advance practice provider-led, multi-disciplinary ACP communication involving the patient, family members, and/or surrogate decision makers. CPT code 99,497, the bas ACP code, requires 16–30 min of time spent on ACP. The CPT code 99,498 is an add-on code for billing each additional 30 min of ACP communication. ACP billing codes require clinicians to include specific documentation elements about the discussion within the associated clinical encounter, including individuals present, voluntary nature, details about completed or available advance directives, medical necessity, and face-to-face time spent.6 While ACP discussions with patients with complex or life-limiting illness may have more imminent applicability to their medical care plans, current ACP billing patterns demonstrate that Medicare beneficiaries with high disease burden receive billed ACP services less frequently than their healthier counterparts.1,7

While ACP consistently demonstrates reduction in end-of-life (EOL) intensive care among persons with serious illness,8,9,10 the impact of ACP on EOL healthcare utilization, including hospice enrollment patterns, remains unclear.11,12 Inconsistent findings about the impacts of ACP billing may lie in attempts to juxtapose studies focused on varying populations, ACP timing, and outcomes. These mixed findings, combined with parallel inconsistencies within the decades-long trajectory of ACP research, have spurred debate about policies focused on increasing ACP uptake.13,14,15,16,17 ACP advocates point to studies demonstrating the role of ACP in promoting clinician and surrogate decision maker alignment with patient preferences, increasing patient and caregiver satisfaction, and decreasing surrogate decision maker distress.13,18 ACP skeptics point to failures, such as stymied clinical translation and inconsistent evidence of its utility, including impact on patient quality-of-life.16 Lack of consensus about the potential benefits of ACP remains coupled with, and exacerbated by, persistently low delivery of these services nationally.19,20

These ACP challenges have downstream implications in diseases of high public health significance, such as heart failure (HF).21 HF currently affects approximately 6.2 million American adults and is expected to affect 8 million American adults by 2030.22,23 HF remains a leading cause of hospitalization and readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries.24 Despite advances in medical therapy, the overall 1-year HF mortality rate among Medicare beneficiaries approaches 30%.22 The prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of HF are even higher among racial minorities.25 The age-adjusted death rate of HF is highest among Black men (118.2 per 100,000). 26 Disparities in HF clinical outcomes are compounded by disparities in ACP delivery; Black and Hispanic patients are less likely than White patients to have had an ACP conversation.27,28

ACP may provide benefits, such as improved quality of life and reduction in depressive symptoms, to individuals living with HF, but many gaps in knowledge persist, including optimal timing and frequency of ACP delivery. 29,30,31 Despite American Heart Association (AHA) guidance delineating ACP as a critical component of HF care management, persons with HF continue to receive billed ACP services infrequently.32,33,34,35,36 This quantitative study aims to determine whether billed ACP services delivered to HF-diagnosed Medicare beneficiaries within the last 12 months of life are associated with changes in the type and quantity of healthcare utilization in the last 30 days of life.

METHODS

Data Source

Data were derived from 2016 to 2020 100% Medicare Standard Analytical Files (SAFs). The SAFs were developed from fee-for-service claims and are maintained by CMS. They contain encounter-level data including but not limited to date of encounter, expenditures, and diagnosis and procedure codes. They also include patient-level data such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, state and county residence, and date of death. For this study, patients were included if they were enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B, aged 65 years or older, died during the study period, and had a diagnosis of HF. Diagnosis codes were taken from the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (eTable 1).37,38 This study was exempt from review by the local institutional review board per institutional policy.

Study Variables

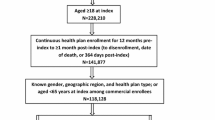

The independent variable of this study was ACP utilization. In alignment with prior ACP literature, we assessed ACP utilization between 1 year and 30 days before death (Fig. 1).11 Patients who received ACP services were identified using CPT codes 99,497 and 99,498. Patients without an ACP encounter were considered controls and propensity score matched to patients with an ACP encounter at a 10:1 ratio on age of death, CCI, and with exact matching on sex, race, region, and year of death. Patient’s region of residence was categorized according to the US Census Bureau.

The outcomes were various measures of EOL healthcare utilization, including total expenditure, as well as five categories of healthcare: inpatient, outpatient, hospice, skilled nursing facility (SNF), and home healthcare (HHC) utilization during the last 30 days of life. For each category, any utilization was recorded as a yes/no and among those who had utilization, the amount of expenditure associated with the utilization. In addition, the number of encounters/admissions and the length of stay were also evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated as median (25th–75th percentiles [IQR]) and frequency (relative frequency [%]) for continuous and categorical measures, respectively. To assess the effect of ACP encounters on EOL healthcare utilization, a range of modeling techniques were utilized. For presence of utilization (yes/no), multivariable logistic regression was utilized to produce odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). For number of encounters/admissions and lengths of stay, multivariable negative binomial regression with a log link was utilized. For expenditure outcomes, multivariable gamma regression with a log link was utilized. For negative binomial and gamma regression models, incidence rate ratios (IRR) and their 95% CIs were estimated. All analyses were performed with an alpha level of 0.05 using SAS v9.4.

Two sets of sensitivity analyses were performed to clarify the effect of ACP on EOL healthcare utilization: analyses stratified by EOL outpatient engagement (i.e., at least one outpatient encounter within the 30-day period before death) and expanding the classification of patients with ACP encounters to delineate between patients with only one ACP encounter and those with multiple ACP encounters.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

A total of 48,466 patients with HF were included in this study (Table 1). Within this sample, 4406 patients had an ACP encounter and 44,060 patients did not have an ACP encounter prior to study end. Approximately half of the cohort were female (51.2%; n = 24,838), 88.1% were white (n = 42,680), the median age was 83 years (IQR, 76–89), and the median CCI was 4 (IQR, 2–5). Given that this cohort is the result of a 10:1 PSM analysis, balance was achieved on all patient factors, including age, race, gender, age, CCI, region of residence, and year of death. Among those patients with at least one ACP encounter, 8.8% (n = 388) had two or more ACP encounters. On overall expenditure, median EOL expenditures were more than $2000 higher among patients with no ACP encounter (ACP, $9890 vs. no ACP, $11,930).

ACP vs. No ACP Encounters

EOL healthcare utilization differed considerably between patients that did and patients that did not have an ACP encounter (Table 1). Outpatient and hospice utilization rates were higher among patients with an ACP encounter: where, 69.2% and 56.1% of patients with an ACP encounter had outpatient and hospice utilization at the EOL, respectively, compared with 46.2% and 49.7% for patients with no ACP encounter. Conversely, patients with an ACP encounter had lower rates of inpatient utilization (ACP, 48.8% vs. no ACP, 57.6%).

Overall EOL expenditure totals were 19% lower (95% CI, 0.77–0.84) among patients with an ACP encounter compared with patients without an ACP encounter (Table 2). Regarding outpatient utilization, patients with ACP encounter had 2.65 times higher odds (95% CI, 2.47–2.83) of having outpatient utilization with an expected total outpatient expenditure 33% higher (95% CI, 1.24–1.42) compared with patients without an ACP encounter. Dissimilarly, ACP encounter patients had 34% lower odds (95% CI, 0.61–0.70) of having an EOL inpatient admission and 31% lower inpatient expenditures (95% CI, 0.64–0.74) compared with patients with no ACP encounter.

Overall EOL expenditures as well as outpatient and inpatient utilization were similar among African-American and White patients (Table 3). Among African-American patients with an ACP encounter, overall expenditures were 16% lower (95% CI, 0.72–0.98) compared with African-American patients without an ACP encounter, while among White patients with an ACP encounter, overall expenditures were 19% lower (95% CI, 0.77–0.84) compared to white patients without an ACP encounter. African-American patients with an ACP had 2.63 higher odds (95% CI, 2.06–3.37) of outpatient utilization and 30% lower odds (95% CI, 0.54–0.89) of inpatient utilization, while White patients with an ACP encounter had 2.65 higher odds (95% CI, 2.47–2.85) of outpatient utilization and 35% lower odds (95% CI, 0.60–0.70) of inpatient utilization.

No ACP vs. 1 ACP vs. Multiple ACP Encounters

The effect of ACP was magnified in cases where a patient had multiple ACP encounters compared with patients who only had one ACP encounter (Table 4). Of note, patients with only one ACP encounter had 18% lower total EOL expenditure (95% CI, 0.78–0.88) whereas patients with multiple ACP encounters had 31% lower total EOL expenditure (95% CI, 0.60–0.79) compared with patients who never had an ACP encounter. Similarly, patients with multiple ACP encounters had lower odds of inpatient utilization (multiple ACP, 0.41 vs. 1 ACP, 0.69), shorter lengths of stay (multiple ACP, 0.47 vs. 1 ACP, 0.70), and less total inpatient expenditure (multiple ACP, 0.50 vs. 1 ACP, 0.71).

End-of-Life Outpatient Engagement

All patient characteristics were well balanced between patients who did and did not have an ACP encounter, irrespective of whether the patient had EOL outpatient engagement (eTables 2 & 3 in the Supplement). An ACP encounter was associated with 19% lower total EOL expenditures (95% CI, 0.78–0.85) among patients with EOL outpatient engagement and 25% lower total EOL expenditures (95% CI, 0.69–0.82) among patients without EOL outpatient engagement (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Diverging from the results of the overall study population, among patients with EOL outpatient engagement, having ACP encounter was associated with 12% decreased outpatient expenditure (95% CI, 0.84–0.92). While the directions of association between ACP encounters as well as inpatient and hospice utilization were similar with the overall cohort, more pronounced effects were observed in the cohort of patients without EOL outpatient engagement. More specifically, an ACP encounter was associated with 45% lower inpatient expenditures (95% CI, 0.48–0.63) among patients without EOL outpatient engagement compared with 28% lower expenditures (95% CI, 0.67–0.78) among patients with EOL outpatient engagement. With regard to any hospice utilization, an ACP encounter was associated with 2.32 times higher odds of utilizing hospice (95% CI, 2.04–2.63) among patients without EOL outpatient engagement compared with 1.36 times higher odds (95% CI, 1.25–1.47) among patients with EOL outpatient engagement.

DISCUSSION

This study finds that individuals with HF who received billed ACP had 25% lower EOL healthcare expenditures compared with propensity score matched controls who did not receive billed ACP. However, this reduction in healthcare expenditure occurred through lower inpatient admission rates, likely substituted by increased outpatient healthcare service utilization, including HHC and hospice. Our findings suggest that the ACP-correlated reduction in healthcare expenditures among HF patients partially results from a shift in where healthcare services are delivered, rather than a reduction of EOL healthcare services. While our data source did not allow exploration of whether this shift reflected alignment with patient goals, recent studies have demonstrated that patients with HF who receive palliative communication overwhelmingly prefer home-based and outpatient EOL care over inpatient care.39

Our findings also demonstrate that persons with HF infrequently receive ACP, despite incremental increases in billed ACP since its inception in 2016, corroborating existing data on ACP trends.19,20 As most individuals with HF nearing the EOL have not received any billed ACP services, our findings suggest a significant opportunity to increase delivery of high value care through the incorporation of systematic billable ACP encounters into comprehensive HF care. Modifying payment policies to prioritize ACP delivery to individuals with HF may incentivize behaviors and processes necessary to increase ACP frequency. Such ACP strategies would not only align with AHA guidance concerning HF care, but may also result in reducing EOL expenditures through promoting outpatient EOL support over hospital-based care. Whichever way they are implemented, HF-focused ACP strategies must also address disparities in ACP delivery to ensure equitable downstream impacts. While our findings demonstrate that billed ACP encounters have a positive impact on outcomes for White and Black patients, our findings demonstrate that Black individuals with HF near the EOL are underrepresented in receipt of billed ACP encounters relative to the proportion of Black Medicare beneficiaries.

Our findings also suggest that iterative billed ACP, a pattern aligning with Institute of Medicine recommendations, 40 was associated with reduced total EOL healthcare expenditures more than a single billed ACP encounter. In addition, progressive increases in outpatient healthcare utilization accompanied reduction in total healthcare utilization among individuals who received 2 billed ACP encounters and 3 + billed ACP encounters respectively.

This study revealed several noteworthy findings, including that ACP was associated with lower rates of EOL inpatient care, higher rates of EOL outpatient care, and higher rates of hospice. While the inverse association of EOL outpatient and hospice care contrasting with inpatient care has been noted previously, this study found that the association of ACP with utilization of EOL outpatient care was more pronounced compared with hospice.41 As such, this study sought to determine whether the association of ACP on EOL healthcare utilization differed by whether a patient had outpatient care at the EOL (coined “EOL outpatient engagement”) in order to determine whether EOL outcomes observed with billed ACP services simply reflected effects resulting from engagement in outpatient care. This not only suggests that ACP is associated with EOL healthcare utilization irrespective of outpatient engagement, but also suggests that for total EOL expenditure, inpatient care, hospice, SNF, and HHC, the effect of ACP was more pronounced among patients without EOL outpatient engagement. Given that prior studies have found that hospice and avoidance of EOL hospitalizations were associated with increased EOL quality of life, these findings suggest that EOL utilization trends associated with billed ACP may act as a surrogate for better quality of life in the last 30 days of life.

Understanding the mechanisms of how billed ACP reduces overall EOL healthcare expenditures while increasing EOL outpatient expenditures fell outside our study scope. Minimum time requirements stipulated by CMS for billed ACP services may help ensure uniformity in ACP communicative “dosing” to individuals. Future research describing the spectrum of communicative content within billed ACP can build knowledge about how clinicians approach billable ACP encounters. The availability of ACP-focused natural language processing technologies and established learning health systems networks (such as the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network) can promote the feasibility of efficient, large-scale evaluation of clinical documentation associated with billed ACP encounters.42,43 Research evaluating the comparative effectiveness of billed ACP employing established universal approaches (such as Serious Illness Communication and ACP electronic templates), HF-specific approaches, and unstructured approaches can inform best practices and guide institutional strategies directed at increasing ACP delivery to persons with HF.44,45

The results of this study should be interpreted considering multiple limitations common with administrative claims research. The most relevant to this study include (1) findings may be confounded due to latent clinical factors such as noncoded or miscoded diagnoses; (2) a lack of clinically nuanced details that are not reflected in ICD-9/10 billing codes; (3) findings may be confounded with clinic practice/network variation in resources, policies, or other latent factors; (4) unmeasured variation in clinician preferences for end-of-life discussion with patients; and (5) unmeasured patient preferences for end-of-life care. Additionally, it is unknown whether the impact reported in this study results from the minimum requirements of ACP billing or whether ACP billing serves as a proxy for goals communication competencies of clinicians using ACP billing codes. Although CMS claims data offer a comprehensive, national view at ACP utilization for Medicare patients, the scope of claims data does not allow for understanding of the ACP processes and communication content driving our findings, limiting the ability to translate specific evidence-based ACP strategies to clinical settings. While our data set did not lend itself to quality-of-life evaluation, our approach focused on evaluating inpatient and outpatient healthcare utilization sought to identify the impact of billed ACP on promoting time patients can spend in their homes and communities near the EOL.

CONCLUSION

Billed ACP delivery to individuals with HF was associated with increased EOL outpatient healthcare use, including HHC and hospice service, while being associated with lower rates of inpatient hospital and SNF utilization. These utilization trends result in an overall decrease in EOL healthcare expenditures. As the minority of patients with HF nearing the EOL receive billed ACP services, strategies directed at increasing ACP delivery to this population, especially among patients facing inequities in ACP delivery, may result in shifting HF EOL support services from inpatient to outpatient settings and increase hospice use. Payment policies designed to prioritize ACP delivery in patients with HF may play a pivotal role in changing behaviors and workflows that further incentivize ACP delivery. Comparative effectiveness research focused on identifying billed ACP best practices to improve delivery rates and quality can help inform evidence-based strategies for clinical translation. Identifying EOL healthcare utilization outcomes associated with billed ACP in other disease states can guide policies and focus resources toward individuals who will most benefit at the EOL. Moreover, future studies should consider primary data collection of provider and practice factors that would increase precision in estimates of ACP utilization and identify possible mechanisms for increasing ACP utilization by detangling associations between ACP utilization and other forms of EOL care.

References

Bose-Brill S, Prater L, Goldstein EV, Xu W, Moss KO, Retchin SM, et al. Primary Care Physician and Beneficiary Characteristics Associated With Billing for Advance Care Planning. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020 2020/05/01;68(5):1108-10.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Innovation Center. BPCI Advanced: Quality Measures. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bpci-advanced/quality-measures-fact-sheets. Accessed December 10, 2022.

Auriemma CL, O’Donnell H, Klaiman T, Jones J, Barbati Z, Akpek E, et al. How Traditional Advance Directives Undermine Advance Care Planning: If You Have It in Writing, You Do Not Have to Worry About It. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2022;182(6):682-4.

Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. The Lancet Oncology. 2017 2017/09/01/;18(9):e543-e51.

Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 May;53(5):821-32.e1.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Billing and Coding: Advance Care Planning. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/article.aspx?articleid=58664. Accessed December 21, 2023.

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine. 2014;28(8):1000-25.

Gupta A, Jin G, Reich A, Prigerson HG, Ladin K, Kim D, et al. Association of Billed Advance Care Planning with End-of-Life Care Intensity for 2017 Medicare Decedents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020 2020/09/01;68(9):1947-53.

Weissman J. Associations between Medicare-Billed Advance Care Planning (ACP) Among Seriously Ill Patients and Their End-of-Life Healthcare Utilization. Health Services Research. 2020 2020/08/01;55(S1):17-8.

Weissman JS, Reich AJ, Prigerson HG, Gazarian P, Tjia J, Kim D, et al. Association of Advance Care Planning Visits With Intensity of Health Care for Medicare Beneficiaries With Serious Illness at the End of Life. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(7):e211829-e.

Prater LC, O'Rourke B, Schnell P, Xu W, Li Y, Gustin J, Lockwood B, Lustberg M, White S, Happ MB, Retchin SM, Wickizer TM, Bose-Brill S. Examining the association of billed advance care planning with end-of-life hospital admissions among advanced cancer patients in hospice. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39(5):504-510. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211039449

Prater LC, Wickizer T, Bower JK, Bose-Brill S. The Impact of Advance Care Planning on End-of-Life Care: Do the Type and Timing Make a Difference for Patients With Advanced Cancer Referred to Hospice? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019 Dec;36(12):1089-95.

Teno JM. Promoting Multifaceted Interventions for Care of the Seriously Ill and Dying. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(4):e221113-e.

Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The Importance of Addressing Advance Care Planning and Decisions About Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders During Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA. 2020;323(18):1771-2.

Mitchell SL. Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2022;327(7):685-6.

Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. What’s Wrong With Advance Care Planning? JAMA. 2021;326(16):1575-6.

Rigby MJ, Wetterneck TB, Lange GM. Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2022;327(7):683-4.

McMahan RD, Tellez I, Sudore RL. Deconstructing the Complexities of Advance Care Planning Outcomes: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? A Scoping Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021;69(1):234-44.

Luth EA, Manful A, Weissman JS, Reich A, Ladin K, Semco R, et al. Practice Billing for Medicare Advance Care Planning Across the USA. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2022 2022/11/01;37(15):3869-76.

Ladin K, Bronzi OC, Gazarian PK, Perugini JM, Porteny T, Reich AJ, et al. Understanding The Use Of Medicare Procedure Codes For Advance Care Planning: A National Qualitative Study. Health Affairs. 2022 2022/01/01;41(1):112-9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart Failure. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/heart_failure.htm. Accessed on December 9, 2022.

Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Mar 3;141(9):e139-e596.

Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013 May;6(3):606-19.

Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for Heart Failure. Circulation. 2012;126(4):501-6.

Lewsey SC, Breathett K. Racial and ethnic disparities in heart failure: current state and future directions. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2021 May 1;36(3):320-8.

Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 2020/03/03;141(9):e139-e596.

Degenholtz HB, Arnold RA, Meisel A, Lave JR. Persistence of racial disparities in advance care plan documents among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Feb;50(2):378-81.

Huang IA, Neuhaus JM, Chiong W. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Advance Directive Possession: Role of Demographic Factors, Religious Affiliation, and Personal Health Values in a National Survey of Older Adults. J Palliat Med. 2016 Feb;19(2):149-56.

Stocker R, Close H, Hancock H, Hungin APS. Should heart failure be regarded as a terminal illness requiring palliative care? A study of heart failure patients’, carers’ and clinicians’ understanding of heart failure prognosis and its management. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2017;7(4):464-9.

Nishikawa Y, Hiroyama N, Fukahori H, Ota E, Mizuno A, Miyashita M, et al. Advance care planning for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Feb 27;2(2):Cd013022.

Schichtel M, Wee B, Perera R, Onakpoya I. The Effect of Advance Care Planning on Heart Failure: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Mar;35(3):874-84.

Ahluwalia SC, Bandini JI, Coulourides Kogan A, Bekelman DB, Olsen B, Phillips J, et al. Impact of group visits for older patients with heart failure on advance care planning outcomes: Preliminary data. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021 2021/10/01;69(10):2908-15.

Bandini JI, Kogan AC, Olsen B, Phillips J, Sudore RL, Bekelman DB, et al. Feasibility of Group Visits for Advance Care Planning Among Patients with Heart Failure and Their Caregivers. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2021;34(1):171.

Gabbard J, Pajewski NM, Callahan KE, Dharod A, Foley KL, Ferris K, et al. Effectiveness of a Nurse-Led Multidisciplinary Intervention vs Usual Care on Advance Care Planning for Vulnerable Older Adults in an Accountable Care Organization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2021;181(3):361-9.

Morris AA, Khazanie P, Drazner MH, Albert NM, Breathett K, Cooper LB, et al. Guidance for Timely and Appropriate Referral of Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021 2021/10/12;144(15):e238-e50.

Palmer MK, Jacobson M, Enguidanos S. Advance Care Planning For Medicare Beneficiaries Increased Substantially, But Prevalence Remained Low. Health Affairs. 2021 2021/04/01;40(4):613-21.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 Mar 15;173(6):676-82.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005 Nov;43(11):1130-9.

Campos E, Isenberg SR, Lovblom LE, Mak S, Steinberg L, Bush SH, et al. Supporting the Heterogeneous and Evolving Treatment Preferences of Patients With Heart Failure Through Collaborative Home‐Based Palliative Care. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2022;11(19):e026319.

Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Medicine Io, editor. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) 2015 March 19, 2015. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285678/

Paredes AZ, Hyer JM, Tsilimigras DI, Mehta R, Sahara K, White S, et al. Hospice utilization among Medicare beneficiaries dying from pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2019 Sep;120(4):624-31.

Lindvall C, Deng C-Y, Moseley E, Agaronnik N, El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. Natural Language Processing to Identify Advance Care Planning Documentation in a Multisite Pragmatic Clinical Trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2022 2022/01/01/;63(1):e29-e36.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The Patient-Centered Network of Learning Health Systems (LHSNet). Available from: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/patient-centered-network-learning-health-systems-lhsnet#project_journal_citations. Accessed December 10, 2022.

Jacobsen J, Bernacki R, Paladino J. Shifting to Serious Illness Communication. JAMA. 2022;327(4):321-2.

Wilson E, Bernacki R, Lakin JR, Alexander C, Jackson V, Jacobsen J. Rapid Adoption of a Serious Illness Conversation Electronic Medical Record Template: Lessons Learned and Future Directions. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2020 2020/02/01;23(2):159-61.

Martino SC, Elliott, MN., Dembosky, J.W., Hambarsoomian, K., Burkhart, Q., Klein, D.J., Mallett, J.S., Haviland, A.M.,. Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Health Care in Medicare Advantage. Baltimore, MD: CMS Office of Minority Health, 2019. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-national-level-results-race-ethnicity-and-gender-pdf.pdf. Accessed on December 10, 2022.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Inspector General. Data Brief: Inaccuracies in Medicare’s Race and Ethnicity Data Hinder the Ability to Assess Health Disparities. Silver Spring, MD: 2022. Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-21-00100.asp. Accessed on December 10, 2022.

Funding

Funding from the Crisafi-Monte Foundation Primary Care Cardiopulmonary Grant Program supported this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bose Brill, S., Riley, S.R., Prater, L. et al. Advance Care Planning (ACP) in Medicare Beneficiaries with Heart Failure. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08604-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08604-1