Abstract

Background

Patterns of opioid use vary, including prescribed use without aberrancy, limited aberrant use, and potential opioid use disorder (OUD). In clinical practice, similar opioid-related International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes are applied across this spectrum, limiting understanding of how groups vary by sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, and long-term risks.

Objective

(1) Examine how Veterans assigned opioid abuse/dependence ICD codes vary at diagnosis and with respect to long-term risks. (2) Determine whether those with limited aberrant use share more similarities to likely OUD vs those using opioids as prescribed.

Design

Longitudinal observational cohort study.

Participants

National sample of Veterans categorized as having (1) likely OUD, (2) limited aberrant opioid use, or (3) prescribed, non-aberrant use based upon enhanced medical chart review.

Main Measures

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical factors at diagnosis and rates of age-adjusted mortality, non-fatal opioid overdose, and hospitalization after diagnosis. An exploratory machine learning analysis investigated how closely those with limited aberrant use resembled those with likely OUD.

Key Results

Veterans (n = 483) were categorized as likely OUD (62.1%), limited aberrant use (17.8%), and prescribed, non-aberrant use (20.1%). Age, proportion experiencing homelessness, chronic pain, anxiety disorders, and non-opioid substance use disorders differed by group. All-cause mortality was high (44.2 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 33.9, 56.7)). Hospitalization rates per 1000 person-years were highest in the likely OUD group (831.5 (95% CI 771.0, 895.5)), compared to limited aberrant use (739.8 (95% CI 637.1, 854.4)) and prescribed, non-aberrant use (411.9 (95% CI 342.6, 490.4). The exploratory analysis reclassified 29.1% of those with limited aberrant use as having likely OUD with high confidence.

Conclusions

Veterans assigned opioid abuse/dependence ICD codes are heterogeneous and face variable long-term risks. Limited aberrant use confers increased risk compared to no aberrant use, and some may already have OUD. Findings warrant future investigation of this understudied population.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Over 10 million Americans misused opioids in 2019.1 However, only 1.6 million met criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD),1 defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as the presence of ≥ 2/11 pre-defined symptoms.2,3 Notably, it does not include withdrawal and tolerance developing with long-term use of prescribed opioids for pain.2,3 Misuse of opioids without OUD can include a range of potentially harmful behaviors (e.g., taking more than prescribed) without meeting OUD criteria.4,5 Those with limited aberrant use comprise a sizeable proportion of those misusing opioids1,4,5 and may be erroneously categorized.6,7 These individuals vary in motivation, specific behaviors, and type of opioid(s) used, making estimating prevalence challenging.4,5,8,9 Existing risk-assessment tools have modest positive predictive value.10,11 Information regarding OUD epidemiology and treatment patterns is often sourced from administrative data including International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes.12,13,14,15,16 This approach presents several challenges. First, ICD codes for OUD include terminology such as opioid abuse, dependence, and withdrawal, which is inconsistent with DSM-5 criteria and may be incorrectly applied in clinical practice.17,18 In recent studies, approximately two-thirds of individuals with an OUD diagnosis code had clinical documentation supporting a high likelihood of DSM-5 diagnosis of OUD on chart review.6,7,19 The remainder either had documentation of limited aberrant opioid use or had prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use for chronic pain. Relying on ICD codes alone also misses many with OUD.20 Furthermore, in a cohort of patients with chronic pain prescribed opioids, different proportions met criteria for ICD opioid dependence, DSM-5 opioid use disorder, and a consensus definition of “addiction.”18

In clinical practice, patients with limited aberrant prescription opioid use are commonly encountered yet poorly understood.4,5 They may not meet DSM-5 OUD criteria, but may have complex dependence interacting with chronic pain.18,21,22,23,24 Limited aberrant prescription opioid use could represent emerging OUD in some patients; if so, application of OUD treatment pathways may be appropriate. Conversely, these behaviors might rarely progress to OUD, but instead indicate uncontrolled chronic pain, other distress, or poor coping, and may resolve if these factors were adequately addressed. Individuals could have a relatively unique disorder reflecting a complex interaction of opioid dependence, pain, and distress that becomes most evident when attempting to taper.24 Thus, better characterization is crucial for developing and testing potential treatments.

Because limited aberrant use is poorly understood, it is unclear whether it confers similar long-term outcomes as OUD, including risk of opioid overdose, hospitalization, and death.25,26,27,28 Some portion of those with limited aberrant use may have elevated risks. Others’ opioid usage patterns may not meaningfully increase risk of harm. A better understanding of how the risk of outcomes (i.e., non-fatal opioid overdose, hospitalization, and mortality) varies according to opioid misuse behavior is a crucial step needed to inform future research.

Therefore, in this study, we used a previously described dataset of randomly selected Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients with an incident OUD diagnosis in their medical records.6 Veterans were grouped as having (1) likely OUD, (2) limited aberrant opioid use, and (3) prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use. We investigated differences in sociodemographic, clinical, and medication factors at the time of diagnosis. We also examined rates of non-fatal opioid overdose, hospitalization, and mortality 3 years after diagnosis. Lastly, we conducted a two-phase machine learning analysis exploring whether those with limited aberrant use more closely resembled those with likely OUD or those with non-aberrant opioid use. The primary motivation was to examine similarities between individuals with limited aberrant opioid use and those with likely OUD (a better-characterized population) to inform future studies in this clinically important but understudied population.

METHODS

Setting, Study Population, and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study combining administrative data with chart review, described in detail previously.6 We obtained data from 2012 to 2017 regarding Veterans’ incident OUD diagnoses via ICD-9/10 codes (Appendix A). A new diagnosis was defined as receiving ≥ 2 identical OUD codes on different days with no other OUD codes in the preceding 2 years. Chart notes from 1 month before and 3 months following diagnosis were reviewed for signs/symptoms of opioid use, misuse, and additional substance use. Subjects were categorized based on the presence of specific criteria in the month before diagnosis. Individuals noted to have the following signs/symptoms were classified as having “likely OUD”: provider noting that individual met DSM-5 OUD criteria; seeking care for and/or requesting specific treatment for OUD; IV/nasal opioid use; infection secondary to opioid use (e.g., abscess); or ≥ 3 aberrant behaviors (e.g., requesting early refills, taking more than prescribed). Patients with ≤ 2 aberrant behaviors, and not otherwise meeting OUD criteria, were classified as having “limited aberrant opioid use.” “Prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use” included medical (analgesic) use of prescribed opioids only. Individuals with insufficient information to classify were not examined further. Appendix B contains details of category determination, including aberrant use criteria. This study was approved by the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

Sociodemographic Factors and Comorbidities

Demographics and clinical information (age, sex, race, ethnicity, homelessness status, rurality of patient address, medical and mental health comorbidities in the year prior to diagnosis) were obtained from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), a VHA administrative data source. Comorbidities were categorized as the presence/absence of cancer, depression, serious mental illness, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorder(s), and additional, non-opioid substance use disorder(s) (SUDs). Homelessness status was obtained from VHA clinic stop codes in the year prior to diagnosis (Appendix A). Information regarding chronic pain presence was abstracted from medical documentation at diagnosis. ICD data were used to calculate the Elixhauser comorbidity index at diagnosis.29

Opioid and Additional Medication Data

Opioid prescriptions were obtained via VHA pharmacy data and/or documentation in the medical record (as some used non-VHA providers to obtain opioids). Use of other prescribed analgesics (gabapentinoids, non-topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants) and benzodiazepines was captured using VHA pharmacy data at time of diagnosis (Appendix C). Use of non-prescribed opioids, including heroin, was determined via chart documentation and included historical/remote use and current use.

Outcomes

Data regarding non-fatal opioid overdose and hospitalization were obtained using ICD codes from the CDW (Appendix A). All-cause mortality was obtained from the Vital Status File, which contains both VA and non-VA vital records.30 Outcomes were ascertained for 3 years following each Veteran’s incident diagnosis and described as age-adjusted rates per 1000 person-years.

Analysis

We categorized patients into three groups: (1) likely OUD, (2) limited aberrant opioid use, and (3) prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use. We examined group differences with respect to sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, and medication use at diagnosis using omnibus tests. Continuous variables were non-normally distributed and compared across the three groups using Kruskal-Wallis H tests. Chi-squared and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. Holm’s method corrected for multiple comparisons.

Hypothetically, a proportion of patients with limited aberrant opioid use could have undiagnosed OUD. Likewise, some may be more similar to those with prescribed, non-aberrant use, and some may have a distinct condition. We conducted a two-stage exploratory analysis to better understand how individuals in the limited aberrant use group compared to those in the other two groups (likely OUD and prescribed, non-aberrant use). First, we trained a binomial logistic regression model using elastic net regularization (ENR) with the sociodemographic, clinical, and medication use data only from those with likely OUD and prescribed, non-aberrant use. We chose ENR because this technique addresses several challenges inherent to standard regression techniques. ENR models are at core similar to traditional regression but have strengths at addressing overfitting and collinearity. Overfitting occurs when a regression line fits training data well but poorly fits novel data, causing falsely strong findings. ENR mitigates this by omitting or reducing the effective strength of variables empirically at high risk of causing overfitting.31 Collinearity in standard regression techniques can make results for either variable difficult to interpret and can lead to inaccurate results.32 By omitting select concerning variables, ENR also reduces collinearity, leaving only variables with the highest discriminatory ability in the model.31 The model training resulted in the ability to assign a probability of individuals in the limited aberrant use group of belonging to either of the other groups. We weighted both likely OUD and prescribed, non-aberrant use groups equally during model training.33 We performed tenfold cross validation on 100 iterations and selected model parameters with the highest average accuracy. We utilized the R “SuperLearner” package34 to compare the performance of multiple machine learning models, finding that multiple model types produced similar accuracy statistics and predicted similar class proportions as our initially chosen model.

In the second phase, we applied the model to individuals in the limited aberrant use group to reclassify them into one of the other two groups. This resulted in a probability for each individual being reclassified as having likely OUD or no opioid use problems. Class reassignment was determined using a cutoff of equal probability, allowing estimation of whether each individual was more similar to those in the other two groups. Model confidence, measured by the distance from equal probability, estimated the degree of association. Thus, probabilities closer to 0 or 1 (and further from 0.5) indicated higher model confidence in class reassignment. Microsoft Access 2016 and R version 3.6.0 were used for data management; the R “glmnet” package was used for data analysis.35

RESULTS

Baseline Differences

Of 483 Veterans, n = 300 (62.1%) were classified as having likely OUD; n = 97 (20.1%) were classified as having prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use. The remainder (n = 86, 17.8%) were categorized as having limited aberrant use. There were significant differences across categories, detailed in Table 1. Most (63.4%) were prescribed opioids at the time of OUD diagnosis. However, this varied from 47.7% in those with likely OUD to 76.7% in those with limited aberrant use (p < 0.001). All in the prescribed, non-aberrant use category were prescribed opioids by class definition. Non-prescribed opioid use (including heroin) was much more common in the likely OUD (67.7%) and limited aberrant opioid use (20.9%) groups than in the prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use group (2.1%, p < 0.001). Non-opioid analgesics were also commonly prescribed with no significant categorical differences.

Age, health, and social factors varied at time of diagnosis. Chronic pain was less common in the likely OUD category (68.2% vs approximately 90% in other categories). Mental health comorbidities were common overall; anxiety disorders and additional SUDs were much more common in those with likely OUD. Nearly one-third of this group experienced homelessness in the year prior to diagnosis compared to < 10% in other categories. There were no significant differences with respect to sex, race, ethnicity, rurality, and other comorbidities.

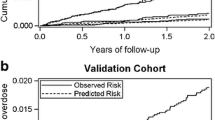

Longitudinal Outcomes

In the 3 years following incident OUD diagnosis, rates of all-cause mortality and hospitalizations were overall high (Fig. 1). Of the 483 individuals, n = 62 (12.8%) died, n = 11 (2.3%) experienced a non-fatal opioid overdose, and n = 282 (58.4%) were hospitalized at least once (mean hospitalizations 3.70 (SD 4.21)). The age-adjusted rate of all-cause mortality was 44.2 (95% CI 33.9–56.7) per 1000 person-years overall. Despite the mean age of those with likely OUD nearly 12 years younger than those with prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use, those with likely OUD trended towards higher all-cause mortality (46.8 (95% CI 33.0–64.5) vs 31.9 (95% CI 16.5–55.0) per 1000 person-years). Those with likely OUD also had the highest age-adjusted hospitalization rates per 1000 person-years (831.5 (95% CI 771.0–895.5)), followed by those with limited aberrant use (739.8 (95% CI 637.1–854.4)). Those with prescribed, non-aberrant use had the significantly lowest rate (411.9 (95% CI 342.6–490.4) per 1000 person-years). The overall age-adjusted non-fatal opioid overdose rate was 7.85 (95% CI 3.92–14.0) per 1000 person-years with no significant group differences.

Age-adjusted rates of outcomes per 1000 person-years. Individuals categorized as having likely OUD had the highest risk of all-cause mortality and hospitalization, followed by those with limited aberrant opioid use. Those categorized as having prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use had the lowest risk. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Exploratory Classification Scheme

The elastic net regularization model identified seven variables as meaningful for prediction of reclassification (Table 2). Factors increasing odds of being reclassified into the likely OUD group included the use of non-prescribed opioids, presence of an anxiety disorder, additional (non-opioid) SUD, and experiencing homelessness. Factors increasing the odds of being classified into the prescribed, non-aberrant use group were older age and being prescribed opioids and muscle relaxants. Upon applying the model to reclassify those in the limited aberrant opioid use category, 29.1% were reclassified into the likely OUD category with a high degree of model confidence. The remaining 70.9% were reclassified into the prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use category with a moderate degree of model confidence (Fig. 2). The model had an internal accuracy of 0.80 (95% CI 0.76–0.84) and a c-statistic of 0.92. Appendix D reports details of model performance metrics.

Estimated probability of individuals in the limited aberrant opioid use group (n = 86) belonging to the other two groups after model reassignment. The cutoff (probability = 0.5) indicates equal probability of reassignment to either group. Individuals assigned probabilities < 0.5 indicate model reassignment to the prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use group. Individuals assigned probabilities > 0.5 indicate model reassignment to the likely OUD group. Increasing distance from the cutoff indicates higher model confidence of class reassignment.

DISCUSSION

This study found that Veterans assigned OUD-related ICD codes are significantly different with respect to age, chronic pain, experiencing homelessness, psychiatric comorbidity, and patterns of opioid use (e.g., prescribed or not). Rates of all-cause hospitalization and mortality were high overall, with likely OUD conferring the highest risk. Using an exploratory machine learning model, we found that nearly one-third of individuals with limited aberrant opioid use shared multiple features with patients with a high likelihood of OUD.

Individuals in all categories had higher age-adjusted all-cause mortality than expected at 44.2 deaths per 1000 person-years.36 Our findings support prior work showing that both OUD and use of prescribed opioids are associated with increased mortality.17,28,37,38 To our knowledge, we provide the first estimate of how all-cause mortality differs when individuals are grouped by OUD likelihood. Specifically, we found that the limited aberrant use group (nearly 20% of this sample) experienced all-cause mortality risk intermediate of the other groups. Those with prescribed, non-aberrant use had the lowest risk, and those with likely OUD had the highest. We also observed markedly high hospitalization rates, more than twice the contemporaneous rate of Medicare beneficiaries.39 Those with likely OUD bore the highest risk, with rates similar to previous reports.40,41 The limited aberrant use group experienced hospitalization rates intermediate of the other groups. The overall number of non-fatal opioid overdoses captured was relatively low; it was similar to rates in other studies of patients prescribed long-term opioids.42 Our longitudinal analysis extends results of cross-sectional studies finding that prescription OUD associates with worse health compared to limited aberrant use, which in turn is riskier than using opioids only as prescribed.43,44 Groups were highly variable both at diagnosis and longitudinally despite identical ICD codes, highlighting the limitations of administrative data alone in identifying OUD.

Limited aberrant use is likely common,4,5 but poorly understood. This category could (a) indicate emerging OUD, (b) primarily reflect patients’ attempts to better control chronic pain (or other distress), or (c) represent a distinct disorder. There is emerging consensus that this group has complex, multidirectional interactions with chronic pain, psychological distress, and physical opioid dependence.4,5,23,24 In some cases, opioid taper attempts precipitate aberrant use.24,45 This group experienced mortality and hospitalization rates intermediate of the others, suggesting that those with limited aberrant use have a meaningfully increased risk of negative outcomes compared to using opioids only as prescribed. Our exploratory machine learning analysis further examined what factors relate to this risk, and how they vary from those with the highest risk (likely OUD) and lowest risk (prescribed, non-aberrant opioid use). Future prospective work should examine whether factors predictive of reclassification into the likely OUD category (e.g., younger age, psychiatric comorbidity, non-prescribed opioid use, and experiencing homelessness) increase risk of developing OUD in the setting of limited aberrant use.

These findings may have implications for treatment. Patients who demonstrate some aberrant opioid use, such as using more than prescribed or repeatedly requesting dose increases, might benefit from specific pathways combining aspects of treatment for OUD and chronic pain.5,46 For example, a combination of transitioning to buprenorphine, which can provide analgesic benefit and potentially reduce harm,22,47,48 along with multi-modal pain treatment5,46 is ripe for further study. Additionally, while a well-validated longitudinal risk prediction model exists for overdose and suicide-related events in Veterans prescribed opioids (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM49)), there is a need for such risk prediction models of those with limited aberrant use. Our study has important limitations. Our sample consisted only of Veterans, who are mostly men, and who have higher rates of OUD, overdose, homelessness, and mortality than the general population.50,51,52,53,54 Additionally, Veterans frequently use both VHA and non-VHA sources of care.55 While mortality data was obtained from both VHA and non-VHA sources, hospitalization and overdose data were only sourced from the VHA and may be underrepresented. In the case of an overdose, a Veteran would likely be brought to the closest non-VHA emergency department. Moreover, inclusion criteria required incident OUD diagnoses made by clinicians, reflecting real-world practice but subject to diagnostic reasoning errors.7,18 We attempted to validate diagnoses with extensive chart review (described in detail previously6), which has inherent limitations compared to real-time clinical assessment. Clinicians are highly variable in decision-making and how completely documentation describes OUD signs/symptoms. However, chart documentation has advantages. It facilitates understanding clinician reasoning and can be conducted at a scale otherwise unfeasible with real-time evaluations. The reclassification model was an exploratory analysis with a relatively small sample size; larger samples are needed to increase confidence. The model only intended to explore similarities and differences of the limited aberrant use group with the other, better understood groups. It cannot diagnose or exclude OUD, nor can it predict longitudinal trajectory.

Conclusion

Veterans assigned an OUD diagnosis code in medical records are highly heterogeneous. Overall, they face higher risks of all-cause mortality and hospitalization than general population samples of similar age. To our knowledge, this study provides the first estimate of how these outcomes differ when individuals with OUD-related ICD codes are grouped according to OUD likelihood. Those categorized as likely OUD were at the highest risk, followed by those with limited aberrant use; those with prescribed, non-aberrant use had the lowest risk. Preliminary analyses focusing on individuals with limited aberrant opioid use suggested approximately one-third share many features of OUD. These findings suggest that a simple binary classification of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain and those with OUD is an over-simplification of the opioid use spectrum. While some with limited aberrant behaviors may have emerging or mild OUD, others may be experiencing a complex, dynamic relationship between chronic pain and opioid dependence, warranting further investigation into different treatment approaches.

References

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publ No PEP19-5068, NSDUH Ser H-54. 2019;170:51-58. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(8):834-851. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782.

Substance-related and addictive disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm16.

Young SR, Azari S, Becker WC, et al. Common and challenging behaviors among individuals on long-term opioid therapy. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):305-310. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000587.

Merlin JS, Young SR, Starrels JL, et al. Managing concerning behaviors in patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain: a Delphi study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):166-176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4211-y.

Lagisetty P, Garpestad C, Larkin A, et al. Identifying individuals with opioid use disorder: validity of International Classification of Diseases diagnostic codes for opioid use, dependence and abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108583.

Howell BA, Abel EA, Park D, Edmond SN, Leisch LJ, Becker WC. Validity of incident opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnoses in administrative data: a chart verification study. J Gen Intern Med. Published online November 11, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06339-3.

Hooten WM, Brummett CM, Sullivan MD, et al. A conceptual framework for understanding unintended prolonged opioid use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(12):1822-1830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.10.010.

Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, Van Der Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1.

Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Miaskowski C, Passik SD, Portenoy RK. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10(2):131-146.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.009.

Bailey RW, Vowles KE. Using screening tests to predict aberrant use of opioids in chronic pain patients: caveat emptor. J Pain. 2017;18(12):1427-1436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.06.004.

Barocas JA, White LF, Wang J, et al. Estimated prevalence of opioid use disorder in Massachusetts, 2011-2015: a capture-recapture analysis. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(12):1675-1681. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304673.

Madras BK, Ahmad NJ, Wen J, Sharfstein J. Improving access to evidence-based medical treatment for opioid use disorder: strategies to address key barriers within the treatment system. NAM Perspect. Published online April 27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.31478/202004b.

Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brissette S, et al. A call for evidence-based medical treatment of opioid dependence in the United States and Canada. Health Aff. 2013;32(8):1462-1469. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0846.

Peterson C, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Florence C, Mack KA. US hospital discharges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011–2015. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;92:35-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.008.

Weiss, A.J., Heslin, K.C., Stocks, C., Owens P. Hospital inpatient stays related to opioid use disorder and endocarditis, 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #256.; 2020. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb256-Opioids-Endocarditis-Inpatient-Stays-2016.pdf

Larney S, Bohnert ASB, Ganoczy D, et al. Mortality among older adults with opioid use disorders in the Veteran’s Health Administration, 2000–2011. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:32-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.019.

Campbell G, Bruno R, Lintzeris N, et al. Defining problematic pharmaceutical opioid use among people prescribed opioids for chronic noncancer pain: do different measures identify the same patients? Pain. 2016;157(7):1489-1498. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000548.

Szalavitz M, Rigg KK, Wakeman SE. Drug dependence is not addiction—and it matters. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):1989-1992. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2021.1995623.

Palumbo SA, Adamson KM, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Assessment of probable opioid use disorder using electronic health record documentation. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15909.

Manhapra A, Arias AJ, Ballantyne JC. The conundrum of opioid tapering in long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a commentary. Subst Abus. Published online September 20, 2017:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2017.1381663.

Chou R, Ballantyne J, Lembke A. Rethinking opioid dose tapering, prescription opioid dependence, and indications for buprenorphine. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(6):427. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-1488.

Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Koob GF. Refractory dependence on opioid analgesics. Pain. 2019;160(12):2655-2660. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001680.

Manhapra A, Sullivan MD, Ballantyne JC, MacLean RR, Becker WC. Complex persistent opioid dependence with long-term opioids: a gray area that needs definition, better understanding, treatment guidance, and policy changes. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(S3):964-971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06251-w.

Bohnert ASBB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.370.

Caudarella A, Dong H, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Wood E, Hayashi K. Non-fatal overdose as a risk factor for subsequent fatal overdose among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:51-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.024.

Singh JA, Cleveland JD. National U.S. time-trends in opioid use disorder hospitalizations and associated healthcare utilization and mortality. Buttigieg SC, ed. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229174.

Bahji A, Cheng B, Gray S, Stuart H. Mortality among people with opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):e118-e132. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000606.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

Maynard C. Ascertaining Veterans’ Vital Status: VA Data sources for mortality ascertainment and cause of death. Published 2019. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/3544-notes.pdf

Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Statistical Methodol. 2005;67(2):301-320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x.

James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Other considerations in the regression model. In: James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, eds. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R. Vol 103. 8th ed. Springer Texts in Statistics. New York: Springer; 2013:82-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7138-7.

Solon G, Haider SJ, Wooldridge JM. What are we weighting for? J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):301-316. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.50.2.301.

Polley E, LeDell E, Kennedy C, Lendle S, van der Laan M. SuperLearner: Super Learner Prediction. Published online 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SuperLearner/index.html. Accessed 11 Aug 2021.

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33(1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v033.i01.

Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2019 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperati. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Accessed 17 Nov 2021.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.7789

Häuser W, Schubert T, Vogelmann T, Maier C, Fitzcharles M-A, Tölle T. All-cause mortality in patients with long-term opioid therapy compared with non-opioid analgesics for chronic non-cancer pain: a database study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01644-4

Keohane LM, Kripalani S, Buntin MB. Traditional Medicare spending on inpatient episodes as hospitalizations decline. J Hosp Med. 2021; October 20. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3699.

Morgan JR, Barocas JA, Murphy SM, et al. Comparison of rates of overdose and hospitalization after initiation of medication for opioid use disorder in the inpatient vs outpatient setting. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029676. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29676.

Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137-145. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3107.

Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006.

Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Jones CM. Correlates of prescription opioid use, misuse, use disorders, and motivations for misuse among US adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5). https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17m11973.

Schepis TS, De Nadai AS, Ford JA, McCabe SE. Prescription opioid misuse motive latent classes: outcomes from a nationally representative US sample. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000037.

Agnoli A, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Magnan E, Jerant A, Fenton JJ. Association of dose tapering with overdose or mental health crisis among patients prescribed long-term opioids. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2021;326(5):411-419. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.11013.

Becker WC, Merlin JS, Manhapra A, Edens EL. Management of patients with issues related to opioid safety, efficacy and/or misuse: a case series from an integrated, interdisciplinary clinic. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2016;11(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-016-0050-0.

Powell VD, Rosenberg JM, Yaganti A, et al. Evaluation of buprenorphine rotation in patients receiving long-term opioids for chronic pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2124152. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24152.

Manhapra A, Becker WC. Pain and addiction: an integrative therapeutic approach. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):745-763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.02.013.

Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000099.

Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Med Care. 2011;49(4):393-396. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27.

Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833-839. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837.

Gordon AJ, Trafton JA, Saxon AJ, et al. Implementation of buprenorphine in the Veterans Health Administration: results of the first 3 years. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2-3):292-296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.010.

Teeters JB, Lancaster CL, Brown DG, Back SE. Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:69-77. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S116720.

Tsai J, Link B, Rosenheck RA, Pietrzak RH. Homelessness among a nationally representative sample of US veterans: prevalence, service utilization, and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(6):907-916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1210-y.

Borowsky SJ, Cowper DC. Dual use of VA and non-VA primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):274-280. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00335.x.

Funding

Dr. Powell was supported in part by the Ann Arbor VA Advanced Fellowship in Geriatrics and National Institute on Aging (T32-AG062043). Dr. Lin was supported in part by a Career Development Award (CDA 18-008) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service. Dr. Lagisetty was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5K23DA047475-02) and US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development (SFT 21-101). Dr. Lagisetty and Dr. Bohnert additionally received support from US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development (SDR 21-107). Dr. Lin serves as a faculty expert for the National Committee for Quality Assurance, through funding from Alkermes. The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors thank Jennifer Thomas for excellent administrative support, Rich Evans for assistance with elastic net regularization model development, Dara Ganoczy for assistance with data extraction, and Aleksandra Zarska for editorial assistance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, V.D., Macleod, C., Sussman, J. et al. Variation in Clinical Characteristics and Longitudinal Outcomes in Individuals with Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis Codes. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 699–706 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07732-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07732-w