Abstract

Objective

To assess the relationship between empathic communication, shared decision-making, and patient sociodemographic factors of income, education, and ethnicity in patients with diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study from five primary care practices in the Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada, participating in a randomized controlled trial of a diabetes goal setting and shared decision-making plan. Participants included 30 patients with diabetes and 23 clinicians (physicians, nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists), with a sample size of 48 clinical encounters. Clinical encounter audiotapes were coded using the Empathic Communication Coding System (ECCS) and Decision Support Analysis Tool (DSAT-10).

Results

The most frequent empathic responses among encounters were “acknowledgement with pursuit” (28.9%) and “confirmation” (30.0%). The most frequently assessed DSAT components were “stage” (86%) and knowledge of options (82.0%). ECCS varied by education (p=0.030) and ethnicity (p=0.03), but not income. Patients with only a college degree received more empathic communication than patients with bachelor’s degrees or more, and South Asian patients received less empathic communication than Asian patients. DSAT varied with ethnicity (p=0.07) but not education or income. White patients experienced more shared decision-making than those in the “other” category.

Conclusions

We identified a new relationship between ECCS, education and ethnicity, as well as DSAT and ethnicity. Limitations include sample size, heterogeneity of encounters, and predominant white ethnicity. These associations may be evidence of systemic biases in healthcare, with hidden roots in medical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in medicine, social and economic factors contribute to 50% of a population’s health status1 (Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Health Canada, 2002), and some estimate that less than 10–15% of mortality is preventable by medical care, with the remainder being attributed to social factors2. For example, citizens living in the 1% or 5% highest income counties in the USA had better health outcomes compared to average US citizens3. In contrast, those with lower socio-economic status had a greater prevalence of psychological and chronic health conditions4. These health disparities arise from historical inequities that result in decreased access to clean environments, housing, quality nutrition, and health care. This in turn predisposes to chronic stress and chronic disease development5.

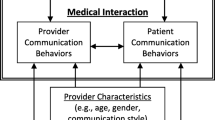

Patient-centered care is a vital component of health care that improves the physical and psychosocial well-being of patients6. Shared decision-making, a component of patient-centered care6, involves assessing the patient’s decision-making needs, providing individualized support and evaluating patient goals to arrive at a quality decision informed by evidence and patients’ values and preferences7. Shared decision-making is associated with improved patient satisfaction and engagement in care8. Shared decision-making is facilitated by empathic communication9; it encompasses the cognitive capacity to understand a patient’s needs, an affective sensitivity to the patient’s feelings, and a behavioral ability to convey this to the patient10. A 2002 meta-analysis of medical interactions in primary care demonstrated that increased physician empathy was associated with increased patient satisfaction, adherence, comprehension, and perception of a good interpersonal relationship11.

Diabetes is a complex chronic disease that disproportionately affects racialized groups and those of lower socioeconomic status worldwide, with these groups experiencing increased prevalence, lower life expectancy, and increased complications of diabetes5. For example, in the USA, the risk of type 2 diabetes is 66% higher in Hispanic people and 77% higher in Black people12 than white people. In Canada, Indigenous people are three to five times more likely to have type 2 diabetes than non-Indigenous people13. Both low income and education are also associated with increased prevalence of diabetes: individuals with lower income and education are two to four times more likely to develop diabetes than more advantaged individuals14. In those with diabetes, low socioeconomic status was associated with a two-fold greater risk of all-cause, cardiovascular- and diabetes-related death compared to high-income counterparts15. A recent population-based study in the UK by Riley et al. (2021) showed that social deprivation is an independent risk factor for developing diabetic foot disease and related complications16.

Health disparities also exist in the receipt of patient-centered care, which may then worsen care gaps. National survey data demonstrate that racialized low-income patients in the USA perceive that they receive less patient-centered care, including less shared decision-making, trust and empathic communication, and as a result are less satisfied with their care17. Similarly, people living in areas of high deprivation (i.e., low income and education) in Scotland perceive their physicians as less empathic and had less desire for shared decision-making18. A survey study found that physicians viewed Black patients and patients of low and middle socioeconomic status as less intelligent, less rational, and less likely to adhere to medical advice or follow-up, than White and high socioeconomic status patients19. Additional studies using audiotapes and videotapes of patient-clinician encounters, as well as patient self-report, demonstrate that clinicians exhibit less empathic and participatory communication (characterized by information sharing and patient involvement in discussion) towards racialized and low income patients20. These implicit biases impact physicians’ communication and clinical decision-making19,20, and may impact patient outcomes.

Specific to diabetes care, clinician empathy has been associated with increased patient satisfaction, quality of life, reduced HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and fewer diabetes complications21. However, little is known about the relationship between social determinants of health, clinician empathy, and shared decision-making in a diabetes-specific population.

Thus, we sought to quantify the relationship between empathic communication, shared decision-making, and sociodemographic factors of income, education, and ethnicity, using validated scales. Our primary objective was to evaluate the relationship between empathic communication and patient education, income, and ethnicity in individuals with diabetes attending primary care clinics in the Greater Toronto Area. The secondary objective was to evaluate the relationship between shared decision-making and patient education, income, and ethnicity in this same population. We hypothesized that patients with lower education, income and from ethnic minorities would experience less empathic communication and shared decision-making compared to those with high education, income, and patients who identified as white.

Specifically, empathic communication will be quantified by the Empathic Communication Coding System (ECCS)10 — an observer-rated measure of empathy, which has not been studied in this context before. Shared decision-making will be quantified by with the Decision Support Analysis Tool-10 (DSAT-10)22 — an observer-rated measure of a clinician’s ability to engage a patient in shared decision-making.

METHODS

Overview and Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study and secondary analysis of clinical encounter transcripts from a large randomized controlled trial that evaluated the impact of interprofessional shared decision-making tools for patients with diabetes and other comorbidities, on decisional conflict23. Sample size was based on 48 available audiotapes from the original study. We reported according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) guidelines for a cross-sectional study (Supplemental Table 1), with details on the original study and recruitment published elsewhere24.

Settings and Participants

The previous study was a 10-site cluster randomized-controlled trial25. The trial recruited 53 clinicians from primary care practice groups across the GTA, one of the most multicultural cities in the world, where 51.5% of the city belonged to a visible minority26. Within each consenting clinician’s practice, patients 18 years of age or older, with diabetes and 2 other comorbidities were randomly selected and invited to participate in a study using a web-based goal-setting and shared decision-making aid via telephone, with a total of 213 patients included. Exclusion criteria included those who did not speak English, had documented cognitive deficits, were unable to provide consent, had limited life expectancy (<1 year), or were not available for a follow-up. In order to assess intervention fidelity during the trial (that is, how was MyDiabetesPlan used during the encounter), 48 clinical encounters were audio-recorded then transcribed. This constituted the data source for the current study.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was empathic communication, measured using ECCS. The secondary outcome was shared decision-making, measured using DSAT-10.

Data Sources

We used patient-reported sociodemographic information and transcripts of clinical encounters. Patients self-reported their ethnicity, education, and income through an online or mailed survey at the start of the prior trial. In the original study, clinical encounters were audiotaped for qualitative analysis to inform future iterations of the shared decision-making intervention. Of note, the prior study also consisted of patient questionnaires for patient-reported outcomes of decisional conflict, diabetes distress, assessment of care, and quality of life; however, these were not used in the present study.

Data Collection Tools

Assessment of Empathic Communication

We conducted qualitative coding of the clinical encounter transcripts to derive a score for empathic communication, using ECCS. ECCS is an observer-rated measure of clinician empathy that measures empathy by examining clinician empathic responses to patient-created opportunities, with responses subsequently categorized on a scale from 0 (denial) to 6 (shared experience) (Supplemental Table 2). Because it is observer-rated, it eliminates biases associated with self-report.

Assessment of Decision Quality

We conducted qualitative coding of the clinical encounter transcripts to derive a score for decision quality using DSAT-10. The DSAT-10 evaluates the clinician’s ability to address the status of the decision; the patient’s knowledge of the options, benefits, and harms; the patient’s values and preferences associated with the decision; assessment of the involvement of others; and the patient’s preferred role in the decision-making and the next steps22. The DSAT-10 scale ranges from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more decisional support during the patient-clinician interaction (Supplemental Table 2). Because it is observer-rated, it eliminates biases associated with self-report.

Data Analysis

Audio-recordings of the clinical encounters were transcribed verbatim and coded independently using ECCS and DSAT by two team members with expertise in qualitative coding. The first 20 transcripts were double coded until an inter-rater agreement of 75% was attained. Coders were blinded to participant characteristics.

We then calculated the weighted average empathy score from the ECCS and the total score from the DSAT-10. The unit of analysis was the transcript, so the average empathy score was calculated by dividing the total score by the number of empathic opportunities per encounter. The DSAT-10 score was reported as a total score out of 10. We a priori selected to evaluate the relationship between sociodemographic factors of education, income, and ethnicity with ECCS and DSAT-10.

Statistical Methods

We used descriptive statistics to describe the characteristics of participants (patients and clinicians) and clinical encounters. For the primary outcome, we used one-way ANOVA to examine the effect of the categorical independent variables (income and education) entered as between-subjects factors, on our continuous dependent variable ECCS. If there was a significant effect of any factor, we conducted exploratory post hoc Tukey’s to determine which groups differed from each other27. For ethnicity (white vs. non-white; binary outcome), we used 2 independent sample t-test. For the secondary outcome, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test to examine the effect of the categorical independent variables (income and education) on our ordinal dependent variable DSAT28. If there was a significant effect of any factor, we conducted exploratory post hoc Dunn tests to determine which groups differed from each other27. For ethnicity, we used Mann-Whitney test. We conducted a Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to correct for multiple comparisons, a moderate false discovery rate of 0.15, given the exploratory nature of this study29. All analyses were done using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.030.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients, Clinicians, and Clinical Encounters

We analyzed a total of 48 clinical encounters, involving 30 unique patients and 23 unique clinicians. Sociodemographic characteristics of patients and clinicians are indicated in Table 1. There were 26 male patients (54%) and 22 female patients (46%). The majority of patients were within the age ranges of 65–74 years old (50%) and retired (64%), with annual income >$60,000 (53%). The sample was primarily white (69%), with income and education being fairly uniform among patient demographics. All patients had type 2 diabetes, with the exception of 1 nonrespondent. Clinicians consisted mostly of family physicians, 61% of which were female, and majority (48%) had more than 16 years of practice (Table 1).

Clinical encounters ranged in length from 3 min 55 s to 1 h 30 min, with a mean length of 31 min 26 s (SD 15 min 33 s). Mean ECCS score across all clinical encounters was 3.5 (standard deviation (SD) = 0.8). The most frequent empathic responses were “acknowledgement with pursuit” (29 %) and “confirmation” (30.0%) (Table 2). Mean DSAT score across all clinical encounters was 3.9 (SD = 1.8). The most frequently assessed DSAT components were the stage of decision-making (present in 86% of encounters) and intervening to provide the knowledge of options (present in 82% of encounters). The least frequently assessed DSAT components were assessing and intervening regarding the preferred role of the patient (present in 16% and 14% of encounters respectively) (Table 3).

Relationship Between Patient Sociodemographic Factors and Empathic Communication (Primary Outcome)

We found that ECCS was varied by education (p=0.030) and ethnicity (p=0.030), but not income (Table 4). Post hoc analyses of the former revealed that patients with only a college degree received more empathic communication than patients with bachelor’s degrees or more, and South Asian patients received less empathic communication than Asian patients (Table 4).

Relationship Between Patient Sociodemographic Factors and Shared Decision-Making (Secondary Outcome)

We found that DSAT varied with ethnicity (p=0.07) but not education or income (Table 4). Post hoc analyses of the former revealed that white patients experienced more shared decision-making than those in the “other” category (Table 4).

To correct for multiple comparisons, we conducted a Benjamini-Hochberg procedure using a conservative false discovery rate of 0.15. The comparison between DSAT and patient ethnicity had the highest P (=0.07) that was less than its critical Benjamini-Hochberg value (0.08), thus confirming that all preceding comparisons (ECCS and ethnicity, ECCS and education) were significant. The rank table is included in Supplemental File 2.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that ECCS was varied by education and ethnicity, such that patients with only a college degree received more empathic communication than patients with bachelor degrees or higher, and South Asian patients received less empathic communication than Asian patients. In addition, we found that DSAT varied by ethnicity, such that white patients received more shared decision-making than non-white patients/“other.”

Interpretation of Findings/Relevance to Literature

These findings are consistent with the existing literature that racialized individuals and those with lower SES perceive less empathy and shared decision-making in healthcare interactions31. However, we found that patients with only college education received more empathic communication compared to those with a bachelor degree or higher, which reveals a new finding that is contrary to the overarching trend in the literature, despite controlling for income and ethnicity32. Although several studies have demonstrated that individuals with low income, education and from ethnic minorities experience less empathic communication and shared decision-making, we provide objectively assessed, quantitative evidence of these relationships, in a clinical population — individuals with type 2 diabetes — that is characterized by ethnic and socioeconomic diversity; these relationships existed despite the study being conducted in a multicultural geographic setting during an era with growing awareness of considerations for equity, diversity, and inclusion.

These associations are concrete evidence of systemic bias in healthcare, with roots in medical education. Empathy decreases throughout medical training33. Further, studies of medical trainees’ attitudes towards racialized populations have demonstrated a “pro-white” bias in empathic communication and treatment, in that medical trainees held false beliefs regarding black patients’ perception of pain which led to under-treatment20. This was confirmed in a systematic review by Hall and colleagues, which showed that healthcare providers have implicit biases in terms of negative attitudes towards people of color, which impacted patient-provider interactions, treatment decisions, and patient health outcomes34. Similarly, patients of lower socioeconomic status perceive less access to care, altered physician-patient interaction (feeling like they are listened to), and differences in management plan (such as reduced diagnostic testing)35. Taken together, strategies must be implemented at the medical education level to foster empathy and address these biases that are often part of the hidden curriculum. Examples of strategies to enhance empathic communication include assessing provider patient-centered communication at the point-of-care, education among peers, and mentorship by clinicians who score highly on patient-rated scales of patient-centered communication36. Strategies to address systemic bias in medical education include standardized anti-racism and anti-bias training37 as well as implementation of a structural competency framework, including improving recruitment, promotion and retention processes of faculty, “stop the line” processes for racism, and the use of a community council to review health equity initiatives and provide feedback on performance38.

Strengths and Limitations

First, our study was limited by small predominantly white sample; however, this was a hypothesis-generating exploratory study wherein we a priori selected specific outcomes and statistically controlled for multiple comparisons. Second, because our findings were based on audio-recordings of clinical encounters alone, we were unable to assess non-verbal empathic communication, a key component of empathic communication18. Third, heterogeneity of appointment type (i.e., follow-up vs. initial appointments) may have resulted in differing levels of empathic communication and shared decision-making, given that shared decision-making is longitudinal in nature occurring over several appointments8. We tried to account for this heterogeneity by adjusting for the number of empathic opportunities per encounter; however, we could not adjust the overall DSAT score based on encounter length because of scale properties. Fourth, we did not examine the impact of clinician factors on empathy or shared-decision-making, including burnout, workload, gender, and training32, which may have influenced our results.

Study strengths include our use of objective third-party observer-rated scales not previously used in this context that reduce bias associated with patient or clinician self-report. Second, we captured representative clinical encounters with different clinicians, including physicians, nurses, and dietitians, consistent with interprofessional diabetes care.

Next Steps and Implications

Our research has implications for medical education, clinical practice, and research. That empathy declines with medical training and that racial biases are prevalent in medical trainees call into question the adequacy of medical education in preparing physicians to care for patients with a lens of social justice. Several professional organizations have advocated for education interventions to prepare medical trainees to care for the needs of a culturally diverse population including cultural competency training39, and incorporating critical reflection and dialogue into curriculum to address biases and assumptions that shape healthcare interactions40. In terms of clinical implications, our research underscores the importance of clinical interventions such as shared decision-making tools to empower patients — in particular racialized individuals and those of lower income and educational attainment — to become involved in their healthcare. Additional supports such as interprofessional teams and peer coaches36 should be leveraged to enable patients in vulnerable groups to play an active role in their care. In terms of implications for research, future studies should confirm our findings, and specifically assess the trend of education level and empathy in a larger and more diverse patient population during chance encounters. Triangulation of objective rating of empathic communication (as in our study) with patient self-report of empathy as well as the patient lived experience using qualitative methodology would enhance our understanding. Future studies could also test the impact of patient-directed interventions (such as peer coaches) as well as clinician-directed interventions (such as professional development regarding implicit bias aimed at improving empathic communication or shared decision-making) in specific vulnerable populations.

References

O’Hara P. Creating social and health equity: adopting an Alberta social determinants of health framework. Published online 2005:25.

Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2014;129 Suppl 2:5-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S203

Emanuel EJ, Gudbranson E, Van Parys J, Gørtz M, Helgeland J, Skinner J. Comparing health outcomes of privileged US citizens with those of average residents of other developed countries. JAMA Intern Med. Published online December 28, 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7484

Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: risks and implications for care. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(11):712-722. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163

Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):60-76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2000;51(7):1087-1110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8

Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD001431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4

Serrano V, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Hargraves I, Gionfriddo M, Tamhane S, Montori V. Shared decision-making in the care of individuals with diabetes. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2016;33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13143

Lown BA, Hanson JL, Clark WD. Mutual influence in shared decision making: a collaborative study of patients and physicians. Health Expect. 2009;12(2):160-174. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00525.x

Bylund CL, Makoul G. Examining empathy in medical encounters: an observational study using the empathic communication coding system. Health Commun. 2005;18(2):123-140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1802_2

Bonvincini KA, Perlin MJ, Bylund CL, Carroll G, Rouse RA, Goldstein MG. Impact of communication training on physician expression of empathy in patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 75(1):3-10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.007

Chow EA, Foster H, Gonzalez V, McIver L. The disparate impact of diabetes on racial/ethnic minority populations. Clin Diabetes. 2012;30(3):130-133. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.30.3.130

Turin TC, Saad N, Jun M, et al. Lifetime risk of diabetes among First Nations and non–First Nations people. CMAJ. 2016;188(16):1147-1153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150787

Hill J, Nielsen M, Fox MH. Understanding the social factors that contribute to diabetes: a means to informing health care and social policies for the chronically ill. Perm J. 2013;17(2):67-72. doi:https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-099

Rawshani A, Svensson A-M, Rosengren A, Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S. Impact of socioeconomic status on cardiovascular disease and mortality in 24,947 individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(8):1518-1527. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-0145

Riley J, Antza C, Kempegowda P, et al. Social deprivation and incident diabetes-related foot disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. 2021;44:9.

Okunrintemi V, Khera R, Spatz ES, et al. Association of income disparities with patient-reported healthcare experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):884-892. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04848-4

Mercer SW, Higgins M, Bikker AM, et al. General practitioners’ empathy and health outcomes: a prospective observational study of consultations in areas of high and low deprivation. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):117-124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1910

Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2000;50(6):813-828. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x

Kaseweter KA, Drwecki BB, Prkachin KM. Racial differences in pain treatment and empathy in a Canadian sample. Pain Res Manag J Can Pain Soc. 2012;17(6):381-384.

Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2012;87(9):1243-1249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf

Guimond P, Bunn H, O’Connor AM, et al. Validation of a tool to assess health practitioners’ decision support and communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(3):235-245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00043-0

Bruno BA, Choi D, Thorpe KE, Yu CH. Relationship among diabetes distress, decisional conflict, quality of life, and patient perception of chronic illness care in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes and other comorbidities. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(7):1170-1177. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-1256

Yu CH, Ivers NM, Stacey D, et al. Impact of an interprofessional shared decision-making and goal-setting decision aid for patients with diabetes on decisional conflict--study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0797-8

Yu C, Choi D, Bruno BA, et al. Impact of MyDiabetesPlan, a Web-based patient decision aid on decisional conflict, diabetes distress, quality of life, and chronic illness care in patients with diabetes: cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e16984. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/16984

Government of Canada SC. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census - Census subdivision of Toronto, C (Ontario). Published February 8, 2017. Accessed September 27, 2020. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-CSD-eng.cfm? TOPIC=7&LANG=eng&GK=CSD&GC=3520005

Dunn OJ. Multiple Comparisons among Means. J Am Stat Assoc. 1961;56(293):52-64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1961.10482090

Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;47(260):583-621. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2280779

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57(1):289-300.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp.; 2011. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software

Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Derese A, De Maeseneer J. Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):139-146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.011

Elayyan M, Rankin J, Chaarani MW. Factors affecting empathetic patient care behaviour among medical doctors and nurses: an integrative literature review. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(03):311-318. doi:https://doi.org/10.26719/2018.24.3.311

Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2011;86(8):996-1009. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60-e76. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

Arpey NC, Gaglioti AH, Rosenbaum ME. How socioeconomic status affects patient perceptions of health care: a qualitative study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(3):169-175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131917697439

Dryden EM, Hyde JK, Wormwood JB, et al. Assessing patients’ perceptions of clinician communication: acceptability of brief point-of-care surveys in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):2990-2999. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06062-z

Ahmad NJ, Shi M. The need for anti-racism training in medical school curricula. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1073. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001806

Gray DM, Joseph JJ, Glover AR, Olayiwola JN. How academia should respond to racism. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(10):589-590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0349-x

Educating medical students for cultural competency: what do we know? (Policy H-295.874).

Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2009;84(6):782-787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Travis Sutherland (University of Toronto) for assistance with coding.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Knowledge-To-Action Grant KAL-129892.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A.B, D.R. and K.G. contributed to literature review, study design, data analyses and drafting of the manuscript. C.H.Y. contributed to statistical analyses, study design, data acquisition and analyses, and manuscript writing. B.A.B., K.G., D.R., and C.H.Y. contributed to revising and providing final approval of the manuscript for publication. C.H.Y. is the guarantor of this work, and, as such, had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted for studies involving human subjects, for the original study, approved by the Research Ethics Board (REBs) of St. Michael’s Hospital (reference number 13-014C), Sunnybrook Health Sciences Health Center (reference number 345-2013), Women’s College Hospital (reference number 2013-0058), Toronto East General Hospital (reference number 609-1410-Mis-245), North York General Hospital (reference number 13-0265), Southlake Regional Health Center (reference number 0055-1314), and Markham-Stouffville Hospital.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Previous Presentations

None.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruno, B.A., Guirguis, K., Rofaiel, D. et al. Is Sociodemographic Status Associated with Empathic Communication and Decision Quality in Diabetes Care?. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 3013–3019 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07230-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07230-5