Abstract

Background

Accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), and the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) generated particular attention during the last decade. Translating these reforms into meaningful increases in population health depends on improving the quality and clinical integration of primary care providers (PCPs). However, if these innovations spread more quickly among PCPs in urban and wealthier areas, then they could potentially worsen existing geographic disparities in health outcomes.

Objective

To determine the market penetration of Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACOs, PCMHs, and the meaningful use of EHRs among PCPs across urban and rural counties in Ohio.

Design

Retrospective, observational study of the percent of PCPs in a county who are affiliated with PCMH, ACO, and meaningful use (MU) of EHR.

Participants

PCPs in all of Ohio’s 88 counties from 2011 to 2015.

Main Measures

Primary care market penetration of ACO, PCMH, and meaningful use of EHR

Key Results

In 2015, the Ohio primary care market penetration of PCMH was 23.4%, ACO was 27.7%, MU stage 1 was 55.8%, and MU stage 2 was 26.6%. During the study period, PCMH and ACO market penetration increased faster in urban counties relative to rural counties, and market penetration of meaningful use of EHR increased faster in rural counties.

Conclusions

Market penetration of PCMH and ACOs increased faster in urban markets compared to rural markets. However, the adoption of EHRs increased faster in rural markets. The results are a cause for optimism as well as a call to action: although recent efforts to increase PCMH and ACO adoption were less effective among the rural population in Ohio, federal programs to accelerate adoption of EHRs were overwhelmingly successful in rural areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Three major developments in health care delivery and payment generated particular attention during the last decade: accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), and the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs). Whereas ACOs tie quality of care to shared savings incentives, PCMHs incentivize integrated care delivery models. These reforms are interrelated: for example, establishing an ACO or PCMH depends on the availability of EHR, and PCMHs are often tied to “payment reform.” Successfully translating these reforms into meaningful increases in population health and cost savings depends, at least in part, on increasing the quality and clinical integration of primary care providers (PCPs). However, it seems unlikely that these innovations would be adopted equally across all parts of the country because they require sizable investments and coordinated efforts across large numbers of diverse care providers to meet the thresholds necessary for participation. These features of adoption anticipate greater uptake of these innovations in urban areas, which typically are served by large integrated health systems, as compared to rural areas, where providers typically are more geographically dispersed and fragmented.1 If these innovations disseminate more slowly among PCPs in rural areas, their potential benefits may fail to reach rural populations, and might potentially increase existing geographic disparities in health outcomes.2,3,4

Despite the high levels of funding targeted to promote adoption of these payment and delivery system reforms, there are limited data which measure national adoption rates among PCPs. State-level data offer a unique opportunity to address this gap because local stakeholders were charged with measuring the adoption of PCMH, ACO, and EHR among specific provider subgroups such as PCPs. We examined county-level penetration of PCMHs, Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, and the meaningful use of EHRs among PCPs across Ohio’s 88 counties. Importantly, we neither assess nor assert the effect of these innovations on population health in Ohio. Instead, we focus on differences in diffusion of PCMH, ACOs, and EHR between urban and rural counties, in part because these three approaches offer different incentives, benefits, opportunities, and challenges for PCPs in urban versus rural areas. Therefore, identifying which approaches to health care delivery transformation were adopted in different market settings can help future health care reform efforts tailor interventions to the differing needs of urban and rural health care markets. We specifically describe how the primary care market penetration of each innovation evolved in the early years of these programs (2011–2015), with an emphasis on potential disparities between urban and rural counties.

METHODS

Measuring Market Penetration

The relationships between PCMH, ACO, and EHR with health care utilization and cost likely depend on uptake among “priority primary care providers,” defined by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) as the “highest priority for delivery system transformation and insurer payments” among providers.3,5 The priority primary care provider category includes physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. We expanded the PCP definition to also include general practitioners and geriatricians because these disciplines also provide frontline primary care in the USA. Throughout the present study, the unit of analysis is at the PCP level.

We used Ohio’s 88 counties to define the geographic boundaries for primary care markets under the assumption that most people receive primary care within their county of residence. We measured the yearly primary care market penetration for each approach (PCMH, ACO, and EHR) as:\( {Y}_{aci}=\frac{PCP_{aci}}{PCP_{ci}} \), where Yaci is the primary care market penetration of approach a in county c and year i, PCPaci is the number of PCPs working in approach a in county c in year i, and PCPci is the total number of PCPs working in county c in year i. The primary care market penetration for each approach was calculated separately, and the approaches are not mutually exclusive.

Data Sources

PCMH

During the study period, the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the Joint Commission (TJC) together accredited over 98% of Ohio’s non-federal PCMH sites, with the majority (about 93%) accredited by NCQA. We obtained data from the Ohio Department of Health describing the site name, address, accreditation start and end dates, and the National Provider Identifier (NPI) of every PCP working in NCQA-accredited PCMH sites in Ohio for the years 2013 through 2015; we obtained similar data from TJC for their accredited sites. We chose the period 2013–2015 because it corresponds with the period of most intense federal and state-level efforts to increase adoption of PCMH and EHR.

We linked these data with a publicly available file from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) containing the NPI, practice location, and scope of every provider’s practice in the country.6

NCQA recognized three levels of PCMH accreditation, with level 3 corresponding to the highest level of engagement with the patient-centered principles that underlie the PCMH approach to health care delivery. We calculated the total number of PCPs working in a PCMH setting in each of Ohio’s 88 counties for each year of the study period. TJC data did not specify the level of PCMH accreditation.

ACO

We obtained data on the number of PCPs working in an ACO setting using the Medicare Shared Savings Program ACO Provider-level Research Identifiable File from CMS.7 This file includes a record of each Medicare ACO and lists the NPI of every provider working in that ACO. We linked this information with CMS’s NPI file and followed an analogous protocol to that described above to extract providers of interest and determine the number of PCPs working in an ACO setting in each of Ohio’s 88 counties for each year of the study period. The first Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) in Ohio began in 2013, and therefore the present study analyzes ACO adoption rates beginning in year 2013.

EHR

The Ohio Health Information Partnership (OHIP), a CMS designated regional extension center, provided data including the NPI of each provider in Ohio who attested to meaningful use of EHR. Meaningful use was defined by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT and CMS, using a three-staged approach beginning in 2011, 2013, and 2015, respectively. Each stage required documentation of greater EHR functionality.8 Incentive payments were provided to eligible health care providers for each successive stage achieved, and providers achieving a higher stage of meaningful use were not allowed to attest to a lower stage during the same year. The OHIP data included the specific stage of meaningful use (MU) attested to in each year of the study period (MU stage 2 was only available for 2014 and 2015). We followed an analogous protocol to that described above to extract providers of interest and determine the number of PCPs that achieved meaningful use of EHR in each of Ohio’s 88 counties for each year of the study period.

Yearly Number of PCPs Per County and County Characteristics

We used data from the 2016–2017 Area Health Resource File to determine the number of non-trainee, non-federal primary care physicians working in each county for each year during the study period.9 Rather than using NPI-based data, we selected the Area Health Resource File because it excludes health care trainees and physicians who work in federal hospitals. Although these two groups of PCPs were eligible to participate in PCMH, they were not eligible to obtain payment for meaningful use of EHR. Data on county-level characteristics were also obtained from the Area Health Resource File.

Comparing Market Penetration Over Time

We compared market penetration in urban counties to rural counties because demographics, socioeconomic environment, political beliefs, and health statistics differ across the urban-rural divide in Ohio. Counties were characterized as urban or rural based on the 6-point scale described by the National Center for Health Statistics.10

RESULTS

Demographics

In 2010, the population of Ohio was 11.5 million with 71% residing in 38 urban counties and 21% residing in 50 rural counties (Table 1). Overall, Ohio’s population characteristics and health care resource levels are similar to national averages, although a greater proportion of Ohio residents are White, have lower income, and are more likely to reside in a rural county.

Primary Care Market Adoption and Dissemination

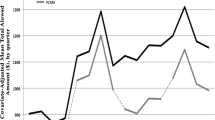

In 2015, the mean market penetration of PCMH (level 1) was 23.4%, Medicare ACO was 27.7%, MU stage 1 was 55.8%, and MU stage 2 was 26.6% (Table 2 and Fig. 1). These averages mask sizable heterogeneity in rates both within and across urban versus rural counties (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

PCMH was adopted more quickly in urban markets than in rural markets, with sustained rapid adoption over the 4-year study period. Trend lines of PCMH adoption between 2011 and 2015 are shown in the top row of Fig. 1 and indicate a closing of the urban-rural gap in later years of the study period.

Only 3 years are available to examine the market penetration of ACOs. From 2013 to 2015, ACO market penetration exhibited a substantial urban-rural gap that increased over time resulting in an almost 70% difference in rates in 2015 (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

In contrast to the pattern observed for PCMH and ACO, meaningful use of EHR was adopted more rapidly among rural markets relative to urban markets (Table 2 and Fig. 1). By 2015, penetration of MU stage 1 had largely stabilized in both rural and urban markets, with rural penetration rates 20 percentage points higher. We also observed a gap in adoption rates favoring rural markets for MU stage 2 in 2015.

DISCUSSION

A potential negative effect of health care innovation is that it will increase pre-existing disparities in access to primary care as manifested by urban-rural differences in its adoption. In our study of the experience in Ohio from 2011 to 2015, PCMH and ACO adoption occurred at a substantially greater rate in urban counties than in rural counties. In contrast, we found that in Ohio, EHR penetration was higher in rural compared to urban areas. This result differs from results using a national sample and reported by Sandefer et al.,11 which show a significantly lower proportion of rural hospitals attested to meaningful use of EHR compared to urban hospitals.

We believe this discordant result is due to the efforts of Ohio’s regional extension centers that specifically targeted rural health care providers in their efforts to increase EHR adoption. No similar programs existed to promote adoption of PCMH or Medicare ACOs among Ohio’s rural primary care providers, and the uptake of these two innovations was predictably slower in rural areas. We therefore regard our findings as a cause both for caution and for optimism. Taken together, our findings suggest that future health policy reform efforts that fail to identify and address the barriers faced in rural health care markets may further entrench existing geographic disparities in access to primary care. However, the experience of EHR adoption in Ohio indicates that this outcome is not inevitable, and that effective, region-specific measures can be employed to mitigate or reverse the disadvantages rural providers face in adopting care innovations.

The varying levels of PCMH adoption across Ohio’s 88 counties likely relate to the size of primary care practices,12,13 extent and intensity of EHR adoption,14 and market-level concentration of PCPs.12 PCMH recognition requires a commitment to care coordination, which may have been easier both to document and to achieve in urban markets with increased local access to specialists. Smaller, more rural primary care practices may have decided that the potential return on investment did not justify the capital expenditure required to obtain PCMH recognition in the early years of the study period. Over time, more insurers (including Ohio Medicaid15) added incentives for PCPs to obtain PCMH recognition while state-wide collaboratives, such as the Ohio Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative, worked to educate PCPs about the potential benefits of PCMH and the necessary integration of EHR in establishing value-driven programs such as PCMH and ACO.16 This shift may have played a role in accelerating the pace of PCMH adoption in more rural primary care markets over time. This explanation highlights the potential role of differing incentives for delivery transformation across urban and rural health care markets and the need for future health care reform efforts to recognize that care coordination (the premise upon which PCMH was developed) has different implementation barriers across urban and rural health care markets.

Our findings that ACOs are less likely to be present in rural areas with fewer specialists agree with those of prior studies.17 Hofler and colleagues18 analyzed over 400 rural, primary care clinics across nine states and found that the mean cost per visit increased by 13.5% among primary care clinics that joined a Medicare ACO compared to a 4.4% increase in clinics that did not join an ACO. Their result suggests that ACO participation imposes substantial costs on rural primary care clinics and lowers participation. Another possible explanation lies in the requirement for Medicare ACOs to serve at least 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries.19 ACOs serving rural areas need to organize providers over large geographic areas, but the costs of doing so might impede their formation. Furthermore, urban providers are increasingly organized into large, integrated health systems, which greatly reduces the organizational cost of establishing an ACO relative to rural areas, where delivery systems are more fragmented.1 The success of the ACO Investment Model (AIM), which specifically addresses the barriers faced by rural health care providers in forming ACOs, illustrates that urban-rural differences in uptake can be averted with policies that target rural health care providers.20 Finally, prior studies have shown that ACO participation rates are higher in more affluent areas.21 As shown in the present study, urban health care markets in Ohio had a higher median household income, suggesting that the observed regional differences in ACO adoption may have also been driven by differences in affluence across urban and rural markets.

Our findings are broadly in keeping with national reports from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology which estimate that in 2015, nearly 54% of office-based providers had at least a basic EHR.22 The same report estimates that EHR adoption rates were plateauing at well below full adoption by 2015, with rates that were similar to state-level aggregates in the present study.22

The success of EHR adoption in rural Ohio likely stems from the concerted efforts made by OHIP and The Health Collaborative (THC), the regional extension centers in Ohio, to engage rural providers in the meaningful use program.23 The role of locally endorsed collaboration models in increasing population health has been documented previously and was influential in Ohio’s decision to expand Medicaid state-wide.24,25 OHIP and THC collaborated with local stakeholders to offer online assessment tools, establish regional educational meetings, and generate a preferred set of EHR solutions, a loan program, and a multifaceted Ohio Vendor Program to encourage rural primary care providers to adopt EHR and attest to stages 1 and 2 of meaningful use.23,26 Focusing on the rural areas of southeast (Appalachia), southwest, and northwest Ohio, the purposeful engagement of rural PCPs likely explains the differential adoption of EHR in rural versus urban markets.

EHR adoption is a central component of future health care delivery and payment reform efforts. Beginning before the passage of the HITECH Act, EHRs have been described as foundational to improving health care delivery and payment, and evidence continues to emerge about the role of EHR adoption on health outcomes among vulnerable populations.27 If EHR adoption is necessary for establishing a PCMH or Medicare ACO, then it is possible that the urban-rural disparities in PCMH and Medicare ACO adoption we observed would have been worse in the absence of faster EHR adoption in rural areas. This finding suggests that the relatively greater uptake of EHR among rural PCPs in Ohio is a cause for optimism for future health care delivery and payment reform efforts in rural areas of the state and country.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting this study. First, the urban-rural disparity in exposure to these innovations ideally would be measured at the patient level. However, data necessary for measuring patient-level exposure are not available. The market penetration measure we used serves as a reasonable proxy for patient-level exposure, under the assumptions that patients (generally) obtain primary care within their county of residence and that patients distribute themselves (roughly) evenly across the PCPs practicing in their county. Violations of either of these assumptions contribute noise to our exposure measure—noise that could influence our penetration measures differentially across urban and rural counties. For example, if a sizable fraction of the rural population obtains primary care outside their county of residence and in an urban county, our PCP-based measure of penetration will tend to exaggerate the “true” differences in exposure across urban and rural residents. Second, some PCPs may work in multiple locations across different counties; our data limited us to attributing each PCP to a single business address. Similarly, there are likely variations in health system affiliation across PCPs in Ohio. Although we attempted to nest PCPs within larger health system affiliations based on business addresses, we were unable to reliably link PCPs with health systems across all health care markets. Finally, although other insurers (including commercial insurers and Ohio Medicaid) also implemented the ACO model during the study period, we were unable to obtain comprehensive data on physician-level participation for non-Medicare ACOs. Therefore, the estimates of ACO market penetration presented in this study are conservative.

CONCLUSION

We found substantial heterogeneity across urban and rural areas in the market penetration of PCMHs, Medicare ACOs, and attestation to meaningful use of EHR. The policy implications of the present findings stem from the remarkable success of the regional extension model in achieving greater adoption of EHR among rural primary care providers that highlights the willingness of rural providers to engage in health care transformation when sufficiently incented. Future health care reform efforts should consider this successful model when designing implementation strategies for delivery and payment innovations in rural areas. In the absence of rural-specific commitments from federal, state, and local stakeholders, the move toward a value-based health care system may exacerbate the health care disparities faced by rural Americans.

References

Cebul, R. D., Rebitzer, J. B., Taylor, L. J. and Votruba, M. E., Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the U.S healthcare system. J Econ Perspect, 2008. 22(4): p. 93-113.

Pollack, C. E. and Armstrong, K., Accountable care organizations and health care disparities. JAMA, 2011. 305(16): p. 1706-7.

Mclaughlin, C. G. and Lammers, E., Geographic variation in health IT and health care outcomes: A snapshot before the meaningful use incentive program began. Healthc (Amst), 2015. 3(1): p. 18-23.

Lewis, V. A., Fraze, T., Fisher, E. S., Shortell, S. M. and Colla, C. H., ACOs Serving High Proportions Of Racial And Ethnic Minorities Lag In Quality Performance. Health Aff (Millwood), 2017. 36(1): p. 57-66.

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 'Regional Extension Centers Program Meaningful Use Milestone,’ Health IT Quick-Stat #36. dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-REC-Program-Priority-Primary-Care-Provider-Meaningful-Use-Milestone.php. 2015.

Crosswalk Medicare Provider/Supplier to Healthcare Provider Taxonomy. [cited 2018 February 1]; Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/MedicareProviderSupEnroll/Downloads/TaxonomyCrosswalk.pdf. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) Provider-level RIF. [cited 2018 February 1]; Available from: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/ssp-aco-provider-level-rif. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Cms. Stages of Promoting Interoperability Programs: First Year Demonstrating Meaningful Use. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stages_ofMeaningfulUseTable.pdf. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Area Health Resource Files. [cited 2017 July 1]; Available from: https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/ahrf.aspx. Accessed 7/1/2020.

NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. [cited 2018 March 1]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Sandefer, R. H., Marc, D. T. and Kleeberg, P., Meaningful Use Attestations among US Hospitals: The Growing Rural-Urban Divide. Perspect Health Inf Manag, 2015. 12: p. 1.

Hing, E., Kurtzman, E., Lau, D. T., Taplin, C. and Bindman, A. B., Characteristics of Primary Care Physicians in Patient-centered Medical Home Practices: United States, 2013. Natl Health Stat Report, 2017(101): p. 1-9.

Gimm, G., Want, J., Hough, D., Polk, T., Rodan, M. and Nichols, L. M., Medical Home Implementation in Small Primary Care Practices: Provider Perspectives. J Am Board Fam Med, 2016. 29(6): p. 767-774.

Landon, B. E., Gill, J. M., Antonelli, R. C. and Rich, E. C., Prospects for rebuilding primary care using the patient-centered medical home. Health Aff (Millwood), 2010. 29(5): p. 827-34.

Patient-Centered Medical Home Summary of Ohio Activity. [cited 2018 February 1]; Available from: https://healthtransformation.ohio.gov/Portals/0/20131015PCMHOhioActivity(2).pdf?ver=2013-11-05-090147-317. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Ohio Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Available from: https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/odh/know-our-programs/Patient-Centered-Medical-Homes/opcpcc/. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Lewis, V. A., Colla, C. H., Carluzzo, K. L., Kler, S. E. and Fisher, E. S., Accountable Care Organizations in the United States: market and demographic factors associated with formation. Health Serv Res, 2013. 48(6 Pt 1): p. 1840-58.

Hofler, R. A. and Ortiz, J., Costs of accountable care organization participation for primary care providers: early stage results. BMC Health Serv Res, 2016. 16: p. 315.

Cms. ACO Providers and Suppliers Information. [cited 2019 01/06/2019]; Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/for-providers.html. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Trombley, M. J., Fout, B., Brodsky, S., Mcwilliams, J. M., Nyweide, D. J. and Morefield, B., Early Effects of an Accountable Care Organization Model for Underserved Areas. N Engl J Med, 2019. 381(6): p. 543-551.

Yasaitis, L. C., Pajerowski, W., Polsky, D. and Werner, R. M., Physicians’ Participation In ACOs Is Lower In Places With Vulnerable Populations Than In More Affluent Communities. Health Aff (Millwood), 2016. 35(8): p. 1382-90.

Health IT Dashboard. Available from: https://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/quickstats.php. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Ohio Health Information Technology Strategic and Operational Plan Profile, presented by The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. [cited 2018 April 19]; Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/oh-plan-summary_updated-2011.12.14-508.pdf. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Tanenbaum, J., Cebul, R. D., Votruba, M. and Einstadter, D., Association Of A Regional Health Improvement Collaborative With Ambulatory Care-Sensitive Hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood), 2018. 37(2): p. 266-274.

Cebul, R. D., Love, T. E., Einstadter, D., Petrulis, A. S. and Corlett, J. R., MetroHealth Care Plus: Effects Of A Prepared Safety Net On Quality Of Care In A Medicaid Expansion Population. Health Aff (Millwood), 2015. 34(7): p. 1121-30.

Ohio Health Information Partnership Program Description. [cited 2018 April 19]; Available from: http://www.ehcca.com/presentations/hiesummitwest1/andres_1.pdf. Accessed 7/1/2020.

Cebul, R. D., Love, T. E., Jain, A. K. and Hebert, C. J., Electronic health records and quality of diabetes care. N Engl J Med, 2011. 365(9): p. 825-33.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanenbaum, J.E., Votruba, M., Einstadter, D. et al. Adoption of Health System Innovations: Evidence of Urban-Rural Disparities from the Ohio Primary Care Marketplace. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1584–1590 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06440-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06440-7