Abstract

Background

Many studies have shown that low health literacy (HL) is associated with several adverse outcomes. In this study, we systematically reviewed the prevalence of low HL in Europe.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, and Scopus were searched. Cross-sectional studies conducted in the European Union (EU), published from 2000, investigating the prevalence of low HL in adults using a reliable tool, were included. Quality was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Inverse-variance random effects methods were used to produce pooled prevalence estimates. A meta-regression analysis was performed to assess the association between low HL and the characteristics of the studies.

Results

The pooled prevalence of low HL ranged from of 27% (95% CI: 18–38%) to 48% (95% CI: 41–55%), depending on the literacy assessment method applied. Southern, Western, and Eastern EU countries had lower HL compared to northern Europe (β: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.40–1.35; β: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.25–0.93; and β: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.06–1.37, respectively). The assessment method significantly influenced the pooled estimate: compared to word recognition items, using self-reported comprehensions items (β: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.15–1.08), reading or numeracy comprehensions items (β: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.24–1.31), or a mixed method (β: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.01–1.33) found higher rates of low HL. Refugees had the lowest HL (β: 1.59, 95% CI: 0.26–2.92). Finally, lower quality studies reported higher rates of low HL (β: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.06–1.07).

Discussion

We found that low HL is a public health challenge throughout Europe, where one in every three to almost one in every two Europeans may not be able to understand essential health-related material. Additional research is needed to investigate the underlying causes and to develop remedies.

PROSPERO Registration

CRD42019133377

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing interest among public health professionals and policy makers in health literacy (HL), which can be broadly defined as “[people’s ability] to make judgements and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve their quality of life”1. Low literacy is a worldwide phenomenon2: limited or non-adequate HL is associated with increased hospitalization3,4, higher rates of medication non-adherence3,5, lower uptake of preventive interventions3, poorer overall health status and increased mortality in the elderly5, as well as an increase in healthcare costs6. Furthermore, low literacy follows a social gradient and reinforces existing inequalities7.

Given its health effects, several European Union (EU) initiatives address HL: in 2007, HL was identified as a policy priority in the European Commission’s health strategy “Together for Health 2007-2013”8; in 2012, improving HL was included among the priorities of the Health 2020 strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe9; and in 2014, the first comparative survey on population literacy across eight EU countries was conducted10. At the international level, the WHO included HL as one of the key health promotion pillars needed for a successful 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 11.

The number of studies on HL has escalated in recent years12; these studies have shown that most patient education material, including explanations of health services and their benefits, are often incomprehensible to a significant proportion of people13. However, small sample sizes, narrowly defined patient populations and heterogeneity in outcomes or study designs have limited the generalizability of the results14, limiting its usefulness for policymaking15. Within this context, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies to quantify the prevalence of low HL in adult people living in EU countries, to provide a quantitative synthesis and estimation of its magnitude at national and European level, and to improve the understanding of the underlying predictive factors.

METHODS

This study was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement16,17. The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42019133377).

Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Inclusion Criteria

Three reviewers searched the bibliographic databases PubMed, Embase, and Scopus using the following string: (“health literacy”[Title/Abstract]) AND (((evaluat*[Title/Abstract]) OR measure*[Title/Abstract]) OR assess*[Title/Abstract]). The string was adapted to fit the search criteria of each database (Supplementary Table 1). No reference librarian was involved. The worldwide discussion on a comprehensive HL definition started at the beginning of the twenty-first century18; therefore, all articles published between 1 January 2000 and 23 June 2019 were retrieved, without restrictions of language or paper type. The search was supplemented by scanning the reference lists of the relevant articles.

Duplicate articles were removed, and the title and abstract of all retrieved records were screened. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were examined by three researchers and reasons for exclusion were recorded. As suggested by Jackson et al.19, we used Google Translate to assess for inclusion of non-English and non-Italian-language articles.

We included any article with the following characteristics: (i) cross-sectional design; (ii) conducted in one or more European Union countries (EU-28); (iii) quantified the prevalence of low HL using a valid and reliable tool; (iv) included people aged 18 years or over.

We excluded articles that investigated only specific HL (e.g., oral HL) that assessed only specific HL domains without providing a general measurement or that did not report the prevalence of low HL in its target population(s).

Data Collection and Quality Assessment

For each record, three reviewers independently extracted the following information: first author, year of publication, tool used to quantify the prevalence of people with low HL, assessment method, number of items of the tool, proportion of people with low HL, sample size, country, EU geographic area, target population, mean or median age of the sample. Supplementary Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of the HL instruments that were used to assess HL and the cut-off scores that were considered to identify people with low HL. The assessment method was classified according to the structure of the tool in four different categories: using word recognition items, using reading or numeracy comprehension items, using self-reported comprehension items, or using a mixed method (i.e., combination of self-reported and reading or numeracy comprehension items). Countries were grouped as North, East, West, and South Europe, according to the United Nations classification20. The target population was classified as general population (i.e., without specific characteristics reported), oncology patients, chronic disease patients, or refugees.

Three independent authors performed the quality assessment of the articles included in the systematic review using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for evaluating cross-sectional/survey studies21. Articles were considered of high quality when the total score was ≥ 7, fair quality if the score was ≥ 5 and < 7, and poor quality if the score was lower than 522.

Statistical Analysis

Since most articles provided two or more prevalence estimates (e.g., in different populations, in different age groups, in different countries, using different tools), we considered each estimate to be a different estimate. They will hereafter be collectively referred to as “studies.”

As in a few reports the same target population was investigated using more than one HL tool, separate meta-analyses were conducted. Specifically, we performed an inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis using a logit transformation of the proportions for each HL assessment method. We pooled estimates using a random effects approach23 and the restricted maximum likelihood method24. The I2 metric was used to test for heterogeneity25.

A random effects meta-regression analysis using logit-transformed prevalence was performed to explore the association between study characteristics and pooled low HL prevalence25,26. The robust variance estimation was used to take into account the correlation between studies27. We ran univariate and multivariable analyses including the covariates that could influence the prevalence estimate based on literature review. The final model consisted of the following variables: geographical area, study quality, assessment method, target population, and mean/median of the sample. The category with the highest number of studies was used as reference for geographic region, target population, and study quality; for the assessment method, we used the category yielding the lowest illiteracy pooled estimate; for the age groups, we followed the natural gradient, using the youngest as reference. For the breakdown of the age categories, we used the cut-off values reported in most studies. All analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp), version 16.0.

RESULTS

Study Selection

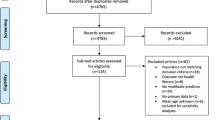

After removal of duplicates, 9120 records resulted from the systematic search (Fig. 1). Screening by title and abstract yielded 134 articles that were then assessed for eligibility. A total of 62 articles were ultimately included in this systematic review, which provided the data of 101 studies (Supplementary Table 3). Since in two reports28,29 the same target population was investigated by different tools but applying the same HL assessment method, only the prevalence estimate coming from the most frequently used tool was included in the meta-analysis, for a total of 99 studies that were pooled.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Proportion Meta-analysis

A similar number of studies was available from countries of the North10,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53, South10,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71, and West EU region10,28,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85 (Table 1). Conversely, only four studies were conducted in the East10,86,87, and two studies referred to refugees from non-EU countries29,88. A consistent heterogeneity was observed among the tools used to assess HL: the most frequently used tools were the Newest Vital Sign, applied in 21 studies42,43,45,47,52,55,56,57,58,63,67,73,77,79,82,84, followed by the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire with 16 items (n = 15)26,27,33,34,38,50,60,71,75,78,83,86 and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (n = 12)30,31,40,41,42,47,48,49,73,76. The European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire with 47 items38,43,55,62,63,78,84,87 and its longer version with 86 items10,58 were used eleven and nine times each, respectively, followed by the Single Item Literacy Screener (n = 8)44,61,65,66,69,82 and the Medical Term Recognition Test (n = 7)56,64,65 (Table 1). The other tools were used in a limited number of studies, from one to three each (Table 1). Most studies investigated HL using self-reported comprehension items26,27,30,33,34,36,38,44,48,49,50,54,55,58,60,61,67,68,70,71,72,74,75,76,78,81,83,85,86 (n = 38); 29 studies used reading or numeracy comprehension items35,37,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,51,52,55,56,57,58,63,67,73,77,79,80,82,84; 23 studies used word recognition items28,29,30,31,32,58,59,62,65,66,79,82; and nine studies used a mixed method10,58. Sixty-six studies quantified low HL in the general population10,26,29,31,32,33,34,36,39,40,43,44,45,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,70,71,73,75,76,78,80,83,84. Patients with chronic diseases were investigated in 25 studies28,35,37,38,41,42,46,49,66,68,69,71,74,77,79,82,85, whereas a smaller number of studies (n = 6) looked at oncology patients47,61,75,80. Only two studies29,88 investigated low HL in refugees. Among the 79 studies reporting it, the age of the sample varied, from 45 years or less in 17 studies30,43,49,56,57,59,64,69,78; between 46 and 64 years in 47 studies26,29,30,34,36,37,38,40,42,43,44,45,49,50,51,54,55,56,57,59,63,67,70,71,73,75,79,80,81,82,84,85; and over 64 years in 15 studies31,33,35,39,41,46,62,66,68,69,70,72,74,77,78. Lastly, the vast majority of studies (n = 81) were rated as high quality10,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,38,39,40,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,55,56,57,58,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,83,84,85,86. Eighteen studies were judged as being of fair or poor quality26,28,36,37,41,44,53,54,59,60,61,82; their main deficits were a lack of justification for the sample size and a lack of comparability between participants and non-participants (data not shown).

Proportion Meta-analysis of Low Health Literacy by Country

Overall, the pooled prevalence of low literacy varied, depending on the assessment method used. Among tools with self-reported comprehension items, low HL was present in 42% (95% CI: 36–48%; df = 37, Q = 3451.2, I2 = 99.5%); reading or numeracy comprehension items was 42% (95% CI: 33–53%; df = 28, Q = 2471.8, I2 = 99.4%); word recognition items was 27% (95% CI: 18–38%; df = 22, Q = 975.5, I2 = 98.3%); and mixed methods provided a pooled estimate of 48% (95% CI: 41–55%; df = 8, Q = 328.0, I2 = 97.7%) (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4).

There was variation in the number of studies in each country as well as the assessment method used. Austria10, Belgium45, Bulgaria10, Croatia68, Czech Republic87, Finland50, Hungary86, Lithuania43, and Poland10 had data available only from one study each. Low HL was common: Austria, 56% (95% CI: 53–53-59%60%); Belgium, 41% (95% CI: 40–42%); Bulgaria, 62% (95% CI: 59–65%); Croatia, 58% (95% CI: 48–67%); Czech Republic, 44% (95% CI: 35–53%); Finland, 36% (95% CI: 31–42%), Hungary, 41% (95% CI: 35–46%); Lithuania, 33% (95% CI: 30–36%); and Poland, 45% (95% CI: 41–48%). Other EU countries had more than one study, often with different assessment tools. Denmark32,35,51,52 low HL was around 44%, in both the assessment methods used (95% CI: 32–58%, df = 1, Q = 12.5, I2 = 92.0%, and 95% CI: 35–54%, df = 1, Q = 0.1, I2 = 0.0%, respectively) (Table 2). France28,82 low HL was 51% (95% CI: 34–67%). Germany10,72,77,78,79,83,84 ranged from 44% (95% CI: 38–51%, df = 11, Q = 681.4, I2 = 98.9%) to 46% (95% CI: 43–49%); Greece10,71 was 45% (95% CI: 42–48%) to 54% (95% CI: 45–63%). In Ireland10,30,37,38,41,42,49, the pooled estimates varied between 19% (95% CI: 17–22%, df = 4, Q = 7.6, I2 = 46.8%), 40% (95% CI: 37–43%), 41% (95% CI: 21–65%; df = 3, Q = 194.9, I2 = 98.4%), and 65% (95% CI: 46–81%). Italy low HL pooled estimates were by self-reported comprehension items61,65,66 42% (95% CI: 33–51%; df = 2, Q = 12.4, I2 = 84.5%); by reading or numeracy comprehension items61,66,67, 38% (95% CI: 35–41%; df = 2, Q = 1.5, I2 = 0.0%); by word recognition items64,65, 72% (95% CI: 32–93%; df = 2, Q = 70.8, I2 = 97.9%); and by mixed method58, 54% (95% CI: 51–57%). As for Portugal54,55,57,59,70, the low HL prevalence estimates varied between 21% (95% CI: 8–46%, df = 5, Q = 86.1, I2 = 96.5%), 29% (95% CI: 6–73%, df = 4, Q = 139.1, I2 = 98.2%), and 50% (95% CI: 48–52%). In Spain10,60,63,69,89, the prevalence estimates of low HL were, in increasing order, 33% (95% CI: 6–80%, df = 1, Q = 55.8, I2 = 98.2%), 43% (95% CI: 34–52%), 58% (95% CI: 55–61%), and 71% (95% CI: 47–87%). In Sweden36,53, low HL ranged from 21% (95% CI: 14–30%) to 39% (95% CI: 36–43%). As for The Netherlands10,73,74,75,76,80,81,85, the highest pooled prevalence was 68% (95% CI: 53–79%; df = 5, Q = 101.0, I2 = 98.5%), followed by 29% (95% CI: 26–32%), 19% (95% CI: 16–23%; df = 2, Q = 2.5, I2 = 0.0%), and 14% (95% CI: 12–15%; df = 1, Q = 0.3, I2 = 0.0%). The UK31,33,39,40,44,46,47,48,90 had relatively low pooled estimates, varying between 16% (95% CI: 12–20%, df = 3, Q = 48.5, I2 = 92.4%), 21% (95% CI: 9–43%, df = 3, Q = 50.8, I2 = 97.2%), and 28% (95% CI: 17–43%, df = 4, Q = 337.2, I2 = 99.4%). Lastly, the refugees’ population was investigated in two studies29,88 with a low HL pooled estimate of 65% (95% CI: 62–69%, df = 1, Q = 2.6, I2 = 60.7%).

Meta-regression Analysis

Meta-regression analysis found that the geographic region, assessment method, target population, and study quality impacted the results (Table 3). Western, Southern, and Eastern countries had higher rates of low HL compared to Northern EU countries. Lower quality studies found higher rates of low HL. There was no difference in literacy by the population assessed (chronic disease, oncology) or the age of the patient. Refugees had the lowest HL.

DISCUSSION

We found that a third to nearly half of Europeans had low HL. This suggests that a significant percentage of people living in EU may have difficulties in getting access to prevention and healthcare services due to limitations in navigation, comprehension, and decision-making7. Although this proportion is slightly lower than that reported by a systematic review of studies on the US population91, where nearly one in two had low HL, and is lower than the mean prevalence of 55% reported in Southeast Asian countries92, our review confirms that low HL also represents a public health challenge in Europe12.

While the prevalence varies considerably by country and the HL assessment method, it seemed to follow a geographic distribution, with the northern countries having lower prevalence than the other EU counterparts. It is possible that the intersection between culture, literacy, and HL may at least partially explain such a difference. Social and cultural context, which includes education, is inextricably linked to how citizens perceive and act on health information93. Countries with the lowest prevalence of low HL also have greater years of education94 and higher socio-economic status95, an important factor in HL96. However, specific future research is needed in order to better investigate the causes of such inequality and appropriately assess their impact on HL.

A widely accepted definition of HL is still under discussion1,97; accordingly, when the researchers used different assessment methods to explore specific HL skills, the prevalence estimates varied significantly. Notably, apart from Italy, tools with word recognition items tended to provide lower illiteracy prevalence estimates, suggesting that investigating HL as medical vocabulary may underestimate the prevalence. Therefore, although the development and acceptance of a universal measure of HL is challenging, a common definition and a comprehensive instrument for its evaluation would enable a more precise estimation of the magnitude of the problem and a better comparison of evidence97.

Older age is reported to be associated with a higher risk of low HL90,91. While we found a slightly increasing, although not significant, trend of low HL prevalence across age groups, the combination of incomplete data and heterogeneity of the measures applied may have limited the reliability of this covariate. However, since older age is known to be associated with an increase in health needs and low HL could impair access to healthcare services14,98,99, the potential effect of aging on HL should not be overlooked.

Differing cultural and educational backgrounds among patients and providers may result in different attitudes and beliefs, which might influence HL and impair access to healthcare services88,93,100,101,102. It was therefore not surprising that we found the strongest association with low HL in refugees, where the lack of knowledge of the healthcare services of the host country, different cultural conceptions, and the language barrier are probably the main drivers of the HL gap103. Since HL is most likely to improve when the messaging and delivery are tailored to the specific needs of individuals and populations97, it is imperative that healthcare systems become more culturally and linguistically competent, so that they are able to address the growing diversity among their target populations13.

Lastly, the study quality was found to be a significant predictor of the prevalence of low HL. Therefore, as reported by WHO Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy15, more high-quality studies are needed in order to properly understand the extent of the challenge and ensure the generalizability of the results. In particular, our study found that more attention should be paid to how the sample is selected, with regard to the justification of sample size and to demonstrating comparability between responders and non-responders.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative synthesis of data on prevalence of low HL in EU countries that enabled a comparison between member States. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, since our objective was to quantify the prevalence of low HL, we included only studies with a cross-sectional design. Second, we excluded articles that used an arbitrary cut-off to identify people with low HL, which provided only a mean measurement of HL, or which analyzed only specific sub-domains. Third, HL tools and target populations were consistently heterogeneous; however, separate analyses and a meta-regression were carried out.

In conclusion, low HL is very common in the EU, where at least one in every three people may not be able to understand essential health-related material. Despite a few variations in the prevalence estimate due to the instrument applied, our results are consistent in showing that low HL represents a public health challenge throughout Europe. Additional efforts to increase the evidence on the underlying causes, to identify areas for intervention, and to implement health practices that effectively address a low level of HL are needed.

References

Sørensen K, Van Den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012;12(1):80.

Heijmans M, Uiters E, Rose T, et al. Study on Sound Evidence for a Better Understanding of Health Literacy in the European Union. 2015.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155(2):97-107.

Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams M V, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health 2002;92(8):1278-1283.

Hope CJ, Wu J, Tu W, Young J, Murray MD. Association of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004;61(19):2043-2049.

Howard DH, Gazmararian J, Parker RM. The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Med 2005;118(4):371-377.

World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts. 2013.

European Commission. Together for Health: A Strategic Approach for the EU, 2008-2013. 2007.

World Health Organization (WHO). A European Policy Framework Supporting Action Across Government and Society for Health and Well-Being. 2013.

Sørensen K, Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur J Pub Health 2015;25(6):1053-1058.

World Health Organization (WHO). The Mandate for Health Literacy. 2017.

Roediger A, Immonen-Charalambous K, Kujawa M, Sørensen K. Nothing about me without me: Why an EU health literacy strategy embracing the role of citizens and patients is needed. Arch Public Health 2019;77(1):10-12.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Schillinger D, Greene SM, Wagner EH. How health care systems can begin to address the challenge of limited literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(8):884-887.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. 199. 2011.

Network M-POHL. Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy. The “Vienna Statement”. 2018.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2017.

Christmann S. Health Literacy and Internet. Recommendations to Promote Health Literacy by the Means of the Internet. 2005.

Jackson J, Kuriyama A, Anton A, et al. The Accuracy of Google Translate for Abstracting Data From Non-English-Language Trials for Systematic Reviews. Ann Intern Med 2019;171(9):677-679.

United Nations. Geographic Regions for Statistical Use. Available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

Hillen M, Medendorp N, Daams J, Smets E. Patient-Driven Second Opinions in Oncology: A Systematic Review. Oncologist. 2017;22(10):1197-1211.

McPheeters M, Kripalini S, Peterson N, et al. Quality Improvement Interventions To Address Health Disparities. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science. Evid Rep No 208. 2012.

Dersimonian R, Laird N. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7(3):177-188.

Langan D, Higgins JPT, Jackson D, et al. A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in simulated random-effects meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods 2019;10(1):83-98.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2003;327(7414):557-560.

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med 1999;18(20):2693-2708.

Hedges L, Tipton E, Johnson M. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Res Synth Methods 2010;1(1):39-65.

Rouquette A, Nadot T, Labitrie P, et al. Validity and measurement invariance across sex, age, and education level of the French short versions of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire. PLoS ONE 2018;13(12):e0208091.

Wångdahl J, Lytsy P, Mårtensson L, Westerling R. Health literacy among refugees in Sweden - A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1030.

Brosnan S, Barron E, Sahm L. Health literacy and the Clozapine patient. R Soc Public Health 2012;132(1):39-42.

Ibrahim SY, Reid F, Shaw A, et al. Validation of a health literacy screening tool (REALM) in a UK Population with coronary heart disease. J Public Health 2008;30(4):449-455.

Juul L, Rowlands G, Terkildsen H. Relationships between health literacy, motivation and diet and physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes participating in peer-led support groups. Prim Care Diab 2018;12:331-337.

Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Limited health literacy is a barrier to colorectal cancer screening in England: Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Prev Med 2014;61:100-105.

Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Health Literacy and Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity During Aging, 2004–2013. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(4):463-472.

Korsbakke Emteaker Hæsum L, Ehlers L, Hejlesen OK. Validation of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults in a Danish population. Scand J Caring Sci 2015;29:573-581.

Lennerling A, Kisch AM, Forsberg A. Health Literacy Among Swedish Lung Transplant Recipients 1 to 5 Years After Transplantation. Prog Transplant 2018;28(4):338-342.

Mackey LM, Blake C, Squiers L, et al. An investigation of healthcare utilization and its association with levels of health literacy in individuals with chronic pain. Musculoskelet Care 2019:1-9.

McKenna VB, Sixsmith J, Barry MM. The relevance of context in understanding health literacy skills: Findings from a qualitative study. Health Expect 2017;20:1049-1060.

Protheroe J, Whittle R, Bartlam B, Estacio EV, Clark L, Kurth J. Health literacy, associated lifestyle and demographic factors in adult population of an English city: a cross-sectional survey. Health Expect 2015;20:112-119.

Rowlands GP, Mehay A, Hampshire S, et al. Characteristics of people with low health literacy on coronary heart disease GP registers in South London: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001503.

Coughlan D, Sahm L, Byrne S. The importance of health literacy in the development of ‘Self Care’ cards for community pharmacies in Ireland. Pharm Pract 2012;10(3):143-150.

Sahm LJ, Wolf MS, Curtis LM, McCarthy S. Prevalence of limited health literacy among Irish adults. J Health Commun 2012;17(3):100-108.

Sukys S, Cesnaitiene VJ, Ossowsky ZM. Is Health Education at University Associated with Students’ Health Literacy? Evidence from Cross-Sectional Study Applying HLS-EU-Q. Biomed Res Int 2017:8516843.

Taylor DM, Bradley JA, Bradley C, et al. Limited health literacy in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016;90:685-695.

Vandenbosch J, Van den Broucke S, Vancorenland S, Avalosse H, Verniest R, Callens M. Health literacy and the use of healthcare services in Belgium. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:1032-1038.

von Wagner C, Knight K, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:1086-1090.

Cox N, Bowmer C, Ring A. Health Literacy and the Provision of Information to Women with Breast Cancer. Clin Oncol 2011;23:223-227.

Dani K, Stobo D, Capell H, Madhok R. Audit of Literacy of Medical Patients in North Glasgow. Scott Med J 2007;52(2):21-24.

Duggan L, McCarthy S, Curtis LM, et al. Associations Between Health Literacy and Beliefs About Medicines in an Irish Obstetric Population. J Health Commun 2014;19:106-114.

Eronen J, Paakkari L, Portegijs E, Saajanaho M, Rantanen T. Assessment of health literacy among older Finns. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019;31:549-556.

Gabel P, Bach Larsen M, Edwards A, Kirkegaard P, Andersen B. Knowledge, attitudes, and worries among different health literacy groups before receiving first invitation to colorectal cancer screening: Cross-sectional study. Prev Med Rep 2019;14:100876.

Heyckendorff Lilholt P, Korsbakke Emtekær Hæsum L, Holger Ehlers L, Hejlesen OK. Specific technological communication skills and functional health literacy have no influence on self-reported benefits from enrollment in the TeleCare North trial. Int J Med Inform. 2016;91:60-66.

Hallelberg Nyman M, Nilsson U, Dahlberg K, Jaensson M. Association between functional health literacy and postoperative recovery, healthcare contacts and health-related quality of life among patients undergoing day surgery. JAMA Surg 2018;153(8):738-745.

Alves E, Costa AR, Moura-Ferreira P, Azevedo A, Lunet N. Health-related knowledge on hypertension among the Portuguese population: results from a population-based survey. Blood Press 2018;27(4):194-199.

Espanha R, Ávila P. Health Literacy Survey Portugal: a Contribution for the Knowledge on Health and Communications. Procedia Comput Sci 2016;100:1033-1041.

Paiva D, Silva S, Severo M, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the health literacy assessment tool METER in the Portuguese adult population. Patient Educ Couns 2014;97:269-275.

Paiva D, Silva S, Severo M, Moura-Ferreira P, Lunet N, Azevedo A. Limited Health Literacy in Portugal Assessed with the Newest Vital Sign. Acta Medica Port 2017;30(12):861-869.

Palumbo R, Annarumma C, Adinolfi P, Musella M, Piscopo G. The Italian Health Literacy Project: Insights from the assessment of health literacy skills in Italy. Health Policy 2016;120(9):1087-1094.

Pires C, Rosa P, Vigário M, Cavaco A. Short Assessment of Health Literacy (SAHL) in Portugal: development and validation of a self-administered tool. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2018:1-18.

Puente-Maestu L, Calle M, Rodríguez-Hermosa JL, et al. Health literacy and health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2016;115:78-82.

Zotti P, Cocchi S, Polesel J, et al. Cross-cultural validation of health literacy measurement tools in Italian oncology patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(410).

Fernández-Silva MJ, Alonso-González A, González-Pérez E, Gestal-Otero JJ, Díaz-Grávalos GJ. Health literacy in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study using the HLS-EU-Q47 questionnaire. Semergen. 2019;45(1):30-36.

Santesmases-Masana R, González-de Paz L, Real J, Borràs-Santos A, Sisó-Almirall A, Navarro-Rubio MD. Alfabetización en salud en pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca atendidos en atención primaria. Aten Primaria 2017;49(1):28-34.

Biasio L, Corbellini G, Dalessandro D. An Italian validation of “METER”, an easy-to-use Health Literacy (HL) screener. Ann Ig 2017;29:171-178. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2017.2144

Biasio L, Lorini C, Abbattista G, et al. Assessment of health literacy skills in family doctors’ patients by two brief, self-administered Italian measures. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2018;54(3):214-222.

Bonaccorsi G, Grazzini M, Pieri L, Santomauro F, Ciancio M, Lorini C. Assessment of Health Literacy and validation of single-item literacy screener (SILS) in a sample of Italian people. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2017;53(3):205-212.

Bonaccorsi G, Lastrucci V, Vettori V, Lorini C. Functional health literacy in a population-based sample in Florence: a cross-sectional study using the Newest Vital Sign. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026356.

Brangan S, Ivanisic M, Rafaj G, Rowlands G. Health literacy of hospital patients using a linguistically validated Croatian version of the Newest Vital Sign screening test (NVS-HR). PLoS ONE 2018;13(2):e0193079.

Castro-Sánchez E, Vila-candel R, Soriano-vidal FJ, Navarro-illana E, Díez-domingo J. Influence of health literacy on acceptance of influenza and pertussis vaccinations: a cross-sectional study among Spanish pregnant women. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022132.

Cavaco A, Santos A. Evaluation of health literacy and the readability of information leaflets. Rev Saude Publica 2012;46(5):918-922.

Efthymiou A, Middleton N, Charalambous A, Papastavrou E. The Association of Health Literacy and Electronic Health Literacy With Self-Efficacy, Coping, and Caregiving Perceptions Among Carers of People With Dementia: Research Protocol for a Descriptive Correlational Study. JMIR Res Protocol 2017;6(11):e221.

Tiller D, Herzog B, Kluttig A, Haerting J. Health literacy in an urban elderly East-German population - Results from the population-based CARLA study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:883.

van Schaik TM, Jørstad HT, Twickler TB, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease among patients with low health literacy. Neth Hear J 2017;25:446-454.

van Der Heide I, Wang J, Droomers M, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Uiters E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: Results from the dutch adult literacy and life skills survey. J Health Commun 2013;18:172-184.

Verkissen MN, Ezendam NPM, Fransen MP, et al. The role of health literacy in perceived information provision and satisfaction among women with ovarian tumors: A study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Patient Educ Couns 2014;95:421-428.

Fransen MP, van Schaik TM, Twickler TB, Essink-Bot M. Applicability of Internationally Available Health Literacy Measures in the Netherlands. J Health Commun 2011;16(3):134-149.

Jordan S, Hoebel J. Gesundheitskompetenz von Erwachsenen in Deutschland: Ergebnisse der Studie “Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell” (GEDA). Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 2015;58(9):942-950.

Berens EM, Vogt D, Messer M, Hurrelmann K, Schaeffer D. Health literacy among different age groups in Germany: results of a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2016;16(1):1-8.

Diederichs C, Jordan S, Domanska O, Neuhauser H. Health literacy in men and women with cardiovascular diseases and its association with the use of health care services - Results from the population-based GEDA2014/2015- EHIS survey in Germany. PLoS ONE 2018;13(12):e0208303.

Husson O, Mols F, Fransen M, van de Poll-Franse L, Ezendam N. Low subjective health literacy is associated with adverse health behaviors and worse health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors : results from the pro fi les. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24:478-486.

Koster ES, Philbert D, Bouvy ML. Health literacy among pharmacy visitors in the Netherlands. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:716-721.

Ousseine YM, Butow PN, Fenaux P, et al. Association between health literacy, communication and psychological distress among myelodysplastic syndromes patients. Leuk Res 2018;73:44-50.

Salm F, Ernsting C, Kuhlmey A, Kanzler M, Gastmeier P, Gellert P. Antibiotic use, knowledge and health literacy among the general population in Berlin, Germany and its surrounding rural areas. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193336.

Schaeffer D, Berens EM, Vogt D. Health literacy in the German population - Results of a representative survey. Deutsch Arztebl Int 2017;114:53-60.

Strijbos RM, Hinnen JW, van den Haak RFF, Verhoeven BAN, Koning OHJ. Inadequate Health Literacy in Patients with Arterial Vascular Disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;56:239-245.

Náfrádi L, Nakamoto K, Csabai M, Papp-Zipernovszky O, Schulz PJ. An empirical test of the Health Empowerment Model: Does patient empowerment moderate the effect of health literacy on health status? Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:511-517.

Rolová G, Barták M, Rogalewicz V, Gavurová B. Health literacy in people undergoing treatment for alcohol abuse – A pilot study. Kontakt. 2018;20(4):e394-e400.

Wångdahl J, Lytsy P, Mårtensson L, Westerling R. Poor health and refraining from seeking healthcare are associated with comprehensive health literacy among refugees: a Swedish cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health 2018;63:409-419.

Fernández-Silva MJ, Alonso-González A, González-Pérez E, Gestal-Otero JJ, Díaz-Grávalos GJ. Alfabetización en salud en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2: un estudio transversal con el cuestionario HLS-EU-Q47. Semergen. 2018;45(1):30-36.

Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, Von Wagner C. Aging and Functional Health Literacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2016;71(3):445-457.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:175-184.

Rajah R, Hassali MAA, Murugiah MK. A systematic review of the prevalence of limited health literacy in Southeast Asian countries. Public Health 2019;167:8-15.

Center for Health Care Strategies. Health Literacy and the Role of Culture. The Fact Sheet. 2013.

Mejer L, Turchetti P, Gere E. Trends in European Education during the Last Decade. 2011.

International Monetary Funds. List of European countries by GDP per capita. http://statisticstimes.com/economy/european-countries-by-gdp-per-capita.php.

Knighton AJ, Brunisholz KD, Savitz ST. Detecting Risk of Low Health Literacy in Disadvantaged Populations Using Area-based Measures. eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes). 2017;5(3):7.

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a population strategy for health promotion. Japanese J Heal Educ Prom 2017;25(3):210-222.

Jaul E, Barron J. Age-Related Diseases and Clinical and Public Health Implications for the 85 Years Old and Over Population. Front Public Health 2017;5:1-7.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health and Aging, Technical Report. National Insititute on Aging. 2011;1(4):273-277.

Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. 2004.

Chiarenza A, Dauvrin M, Chiesa V, Baatout S, Verrept H. Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19(1):1-14.

Graetz V, Rechel B, Groot W, Norredam M, Pavlova M. Utilization of health care services by migrants in Europe - A systematic literature review. Br Med Bull 2017;121(1):5-18.

Ingleby D. Acquiring health literacy as a moral task. Int J Migr Health Soc Care 2012;8(1):22-31.

Funding

This study was carried out as part of the EU-funded project “Adult Cognitive Decline Consciousness”; project code 2017-1-IT02-KA204-036825. This research and its content reflect the views of the authors only, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentation

Ongoing results of this study were presented during the 12th European Public Health Conference held in Marseille, France, 20–23 November 2019.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 1146 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baccolini, V., Rosso, A., Di Paolo, C. et al. What is the Prevalence of Low Health Literacy in European Union Member States? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 753–761 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06407-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06407-8