Abstract

Background

Medication errors are prevalent in healthcare institutions worldwide, often arising from difficulties in care coordination among primary care providers, specialists, and pharmacists. Greater knowledge about care coordination surrounding medication safety incidents can inform efforts to improve patient safety.

Objectives

To identify strategies that hospital and outpatient healthcare professionals (HCPs) use, and barriers encountered, when they coordinate care during a medication safety incident involving an adverse drug reaction, drug-drug interaction, or drug-renal concern.

Design

We asked HCPs to complete a form whenever they encountered these incidents and intervened to prevent or mitigate patient harm. We stratified incidents across HCP roles and incident categories to conduct follow-up cognitive task analysis interviews with HCPs.

Participants

We invited all physicians and pharmacists working in inpatient or outpatient care at a tertiary Veterans Affairs Medical Center. We examined 24 incidents: 12 from physicians and 12 from pharmacists, with a total of 8 incidents per category.

Approach

Interviews were transcribed and analyzed via a two-stage inductive, qualitative analysis. In stage 1, we analyzed each incident to identify decision requirements. In stage 2, we analyzed results across incidents to identify emergent themes.

Key Results

Most incidents (19, 79%) were from outpatient care. HCPs relied on four main strategies to coordinate care: cognitive decentering; collaborative decision-making; back-up behaviors; and contingency planning. HCPs encountered four main barriers: role ambiguity and constraints, breakdowns (e.g., delays) in care, challenges related to the electronic health record, and factors that increased coordination complexity. Each strategy and barrier occurred across all incident categories and HCP groups. Pharmacists went to extra effort to ensure safety plans were implemented.

Conclusions

Similar strategies and barriers were evident across HCP groups and incident types. Strategies for enhancing patient safety may be strengthened by deliberate organizational support. Some barriers could be addressed by improving work systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

In 2017, the World Health Organization declared medication safety a global patient safety challenge.1 Medication errors commonly occur in healthcare institutions worldwide,1 frequently arising from inadequate care coordination among healthcare professionals (HCPs),2 despite HCPs’ best intentions. Medication errors are defined as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.”3 Medication errors are estimated to occur with about 10–20% of medication orders.4 Medication errors can result in adverse consequences for patients, including suboptimal treatment, hospital readmission, and fatality.5,6 In the USA, the economic cost of caring for patients with medication-associated errors is more than $40 billion annually.7 Inadequate care coordination is associated with more than double the odds of error.2

Care coordination involves management of a patients’ care between two or more individuals, such as primary care physicians, hospitalists, pharmacists, and patients themselves.8,9 Errors can occur throughout the medication use process, during prescribing, transcribing, supply, dispensing, administration, monitoring, and documentation. Medication hazards include duplicates, confusion about dosing schedules, and drug-drug interactions (DDIs). Because so many patients are harmed by medication errors,1 identifying and strengthening coordinating activities among HCPs is essential for safety.

Most published studies of medication coordination focus on a specialized care setting (e.g., home nursing care10), vulnerable population (e.g., older adults11), or specific safety task, such as a care transition.12 Patel et al. point out a knowledge gap, that few studies examine error recovery in healthcare,13 which involves detecting and correcting potential errors to solve problems.14 Greater knowledge about how HCPs detect and respond to medication incidents in inpatient and outpatient settings could inform safety improvements. Therefore, as part of a larger study,15,16 we captured incidents where HCPs attempted to prevent or rectify a medication-related problem, to identify their decision-making needs. The objective of our larger study was to identify the cognitive needs of HCPs as they made decisions regarding three categories of incidents: adverse drug reactions (ADR; i.e., medication-related allergy or side effect), DDIs, and renal-drug concerns.15,16 We collected data on their communication strategies and resources used, including who they consulted to help address medication safety incidents. Thus, we also captured data pertaining to HCPs’ coordinating activities.

OBJECTIVE

Our objective for this article was to identify strategies used by hospital and outpatient HCPs, and barriers encountered, as they attempted to coordinate care to detect, prevent, and correct an incident involving an ADR, DDI, or drug-renal concern.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted cognitive task analysis17,18 with HCPs at a tertiary Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center to identify cognitive tasks that occur during medication safety incidents. This method consists of specialized interview and analysis methods to elucidate individuals’ cognitive processes during challenging situations.17,18 Of the cognitive tasks analysis methods,19 we chose the critical decision method interview technique.18 This established, semi-structured interview technique is used to reconstruct real-life incidents and capture detailed accounts of an individual’s information-gathering and problem-solving strategies. The interviewer asks questions to reconstruct a timeline of events, capture the individual’s goals during the incident, identify cues that aided decisions, and uncover strategies used to solve problems.20 A detailed description of the interview method is available in our published study protocol.15

HCPs provided informed consent. We collected data from HCPs on ADRs, DDIs, and renal-drug concerns (see examples in Online Appendix).16 We chose these categories since these incidents occur with commonly prescribed medications; represent different decision-making variables, possible actions, and potential consequences for the patient; and are associated with high patient safety risks. Study methods were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board and VA Research and Development Committee. This article was prepared according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.21

Participants

For the larger study,15 we invited all eligible physicians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists working in inpatient or outpatient care to participate. Physicians and nurse practitioners were eligible to participate if they had prescribing privileges for patients. Staff and clinical pharmacists were eligible to participate if they had prescribing privileges, managed medications, or verified prescriptions. We excluded resident housestaff, trainees, and pharmacy technicians. HCPs could complete up to 3 interviews, 1 for each incident category.

Data Collection

Participants submitted incidents to researchers via a form15 that we developed to capture incident details close to the time of occurrence. Our published protocol depicts this form and describes its development.15 We pilot tested this form with the three types of HCPs and iteratively improved it prior to data collection. We asked HCPs to complete this form when they identified or managed a medication safety incident, which for this study, we defined as a medication concern corresponding to an ADR, DDI, or renal-drug concern where the HCP took any type of clinical action to address the problem. HCPs could submit incidents involving any stage of the medication use process. The form15 consisted of several items, including “I used these resources to assess or respond to the potential [concern],” with response options of “consulted the ordering provider,” “consulted another provider,” and “pharmacist consultation,” among other responses. HCPs’ submissions were screened by a physician and pharmacist according to five dimensions:

-

i.

Incident appropriately addressed;

-

ii.

Incident could cause serious injury/harm;

-

iii.

Incident required great expertise/coordination/consideration;

-

iv.

Incident was challenging or unique; and

-

v.

Incident resolution is likely harder for trainees than experienced HCPs.

Reviewers rated each dimension on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). An incident was selected for an interview when dimensions i and ii were rated as a “4” or above, with other items rated “3” or above. Interviews occurred within about 1 month after each incident.15 Data were collected between September 2013 and September 2015.

Critical decision method interviews were conducted by a human factors scientist with training in cognitive task analysis and medication safety expertise. This individual conducted each interview. One remote participant was interviewed by phone; all other interviews were conducted face-to-face. The semi-structured interview guide15 allowed the interviewer to ask tailored, emergent questions related to the context of individual incidents. Participants could access the electronic health record (EHR) during interviews to reconstruct incident timelines and answer questions. The interview guide15 included six questions about care coordination:

-

1.

Who, if anyone, did you interact with to help resolve the medication conflict?

-

2.

What, if any, documentation in the EHR helped you know what to do?

-

3.

What were your goals for the discussion with the [physician/pharmacist/patient]?

-

4.

What, specifically, did you want to learn from the [physician/pharmacist/patient]?

-

5.

What, specifically, did you want to convey to the [physician/pharmacist/patient]?

-

6.

What, if any, coordination challenges did you encounter within the organization to manage the medication conflict?

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim via a medical transcription service, and de-identified for analysis.

Incident Selection for Care Coordination Analysis

For the larger study, 315 HCPs were invited to participate, 45 enrolled (14% response rate), none replied with refusal to participate, and 39 submitted at least one incident (87% participant response).15 The mean (SD) time from incident occurrence to form submission was 7 (8.5) days.15 We completed cognitive task analysis interviews on a total of 60 incidents: 20 ADRs, 20 DDIs, and 20 drug-renal incidents.16 Interview duration varied to accommodate participants’ availability and incident complexity, with a mean duration of 47 (10.3) min.15 Nurse practitioners completed only three interviews (Fig. 1), and since this sample was insufficient to compare themes across HCP types, we excluded these interviews from this analysis. Otherwise, incidents were eligible for the care coordination analysis if any of these criteria were met: a handoff occurred between HCPs22; there was a gap in coordination for medication management; the HCP contacted, or was contacted by, another HCP regarding the incident; or the HCP monitored the patient to ensure that recommended follow-up occurred with another HCP. We created a stratified random sample from eligible incidents (Fig. 1). To ensure even sampling, we stratified incidents across the three incident categories, and across participants’ professional role, and then randomly selected incidents from these strata for analyses. Microsoft Excel was used to randomize the order of eligible incidents. Since saturation of qualitative themes is often achieved within 12 interviews,23 we randomly selected 24 incidents total from these strata. When a HCP completed more than one interview,15 we only analyzed the first incident in the randomized sequence. We analyzed incidents in blocks: ADR incident from a physician and pharmacist; DDI incident from a physician and pharmacist; and drug-renal incident from a physician and pharmacist. We repeated this process, in this order, to analyze incidents.

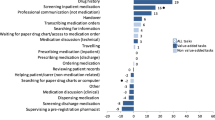

Diagram of medication safety incident selection. Incidents were randomly selected for care coordination analysis from the eligible sample and were stratified by incident category and type of healthcare professional. ADRs, adverse drug reactions; CDM, critical decision method; DDIs, drug-drug interactions, HCP, healthcare professional; MD, physician; NP, nurse practitioner; PharmD, pharmacist.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis was conducted iteratively from January 2014 to February 2016, in two stages. In stage 1, a human factors engineer and pharmacist independently analyzed each incident.16 Following an established approach for cognitive task analysis that utilizes a template known as a “decision requirements table,”24 these analysts then met to discuss findings and develop a set of decision requirements for each incident. This template provides a structured format for each analyst to list HCPs’ decisions, associated strategies, challenges encountered, and potential system solutions. Rather than using interrater reliability, analysts discussed discrepancies until reaching consensus, which is an equally valid approach.25 This approach precludes interrater reliability but allowed us to integrate analysis findings from clinical and human factors experts to generate one set of decision requirements per incident.25 In stage 2, we conducted an inductive, qualitative analysis to identify emergent themes across incidents.25,26 This analysis team included a human factors expert, medication safety pharmacist, sociologist, and research assistant. The latter two independently coded incidents with initial themes, and then discussed discrepancies until reaching consensus.25 Data that might represent new themes were brought to the analysis team and discussed until reaching consensus.25 Codes were entered into NVivo software (version 10, QSR International Inc., Chadstone, Victoria, Australia); multiple codes were assigned if data clearly related to multiple themes.27 To maintain quality, we randomly chose incidents periodically such that, altogether, 7 (29%) of the incidents were independently analyzed by each of the 4 analysts and then discussed as a team until reaching consensus.28 To assess clarity and face validity of the results,29 findings were presented monthly to the entire research team. Findings were iteratively discussed at these meetings to facilitate a robust analysis process that included pharmacist, physician, and human factors perspectives.

RESULTS

Qualitative Themes

Analysis required 112 person-hours of consensus meetings. No new themes emerged after the first 12 incidents, indicating adequate data saturation. Table 1 summarizes participants. Tables 2 and 3 provide theme definitions. See the Online Appendix for theme distribution and supplemental quotes.

Strategies

HCPs used four strategies (Table 2) during each of the three types of incidents. Each strategy was used by physicians as well as pharmacists, unless otherwise noted. First, HCPs drew upon cognitive decentering,30 by assuming the perspective of another HCP to construct a mental picture of other providers’ mental model of the safety concern. This shaped their own mental model of the situation, and informed subsequent actions. Second, HCPs contacted each other to offer solicited or unsolicited pharmacotherapy recommendations, and to engage in collaborative decision-making about drug-related therapy. Internal cues, such as uncertainty, discomfort, or urgency, compelled HCPs to contact peers or those with specialized knowledge. HCPs often sought common grounding (e.g., reviewed the EHR “together”) or concordance (e.g., “both of us agreed”). Agreements served as cues to HCPs to proceed with actions.

Third, HCPs used back-up behaviors31 during incidents. For example, one physician faxed and called a home-care agency, to ensure that an unsafe medication was removed from the patient’s pill box. Five pharmacists described how they often “check back up on patients” to determine whether a provider implemented their medication recommendation, and to ensure that the situation has been addressed. If not, they reminded the HCP, accordingly. Pharmacists developed personalized tracking methods via notes, printouts, monitoring alerts, and keeping files. One pharmacist stated, “…technically, you don’t have to [do this for the job]... a normal [pharmacist] who works [in the call center] on a regular basis doesn’t have time to go back in and check on all these things.” Physicians did not report this tracking activity. Finally, HCPs conceived contingency plans, consisting of alternative steps they would take if some aspect of the incident changed or their interventions were unsuccessful. Contingency plans, unlike back-up behaviors, were hypothetical and not performed for study incidents (at least at the time of the interview), but potentially valuable for future use.

Barriers

Each barrier (Table 3) was encountered during each incident category, and hindered physicians and pharmacists. First, role ambiguity and constraints consisted of reported problems or confusion regarding HCPs’ clinical responsibilities, hindering incident resolution, and included impediments related to pharmacists’ limited authority, e.g., “…in my role as a clinical pharmacist I would’ve just taken care of it all but, …my [other hospital] role doesn’t have that same authority. I’m not embedded in the clinic where [with] the doctors [I can] say, ‘I’m just gonna take care of this for you, and this guy can stop this [medication].’” Second, breakdowns in care were common. Breakdowns often impeded coordination or prompted the need for additional coordination. Breakdowns sometimes escalated concerns, stalled patients’ treatment, or waylaid safety interventions. Third, EHR-related challenges included several aspects (Table 3), along with insufficient or buried clinical documentation within the EHR. A hospital physician shared, “I just happened upon this statement…that said, ‘DO NOT SEND HIM HOME ON AN ACE OR AN ARB’ [but no rationale was given]….” Fourth, complexity involved organizational, team, and patient-related factors that complicated the coordination of incidents. Organization and team factors included inconsistencies in patients’ provider (e.g., rotating residents); managing care across multiple HCPs or institutions; inability to reach other HCPs; and uncertainty about whether another HCP could be reached, along with inability to predict the timeliness of their response. Patient-related factors included unfamiliarity with the patient’s medical history (e.g., new patient), inability to communicate directly with the patient, and a patient with an unclear clinical baseline or uncertain future clinical trajectory.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first in-depth studies to examine HCPs’ coordination of medication incidents across multiple clinical problems and settings. Our study adds to scientific knowledge by identifying medication-related coordinating strategies. Additionally, we discuss four important findings: alignment between HCPs’ coordinating strategies and high-reliability principles32; pharmacists’ tracking of patients to ensure safety; role ambiguity; and implications of EHR communication for medication safety.

HCPs’ strategies align with some principles of high-reliability organizations that other industries have used to achieve high levels of safety, but are not yet widely implemented in healthcare.32 For example, HCPs’ cognitive decentering and exchange of pharmacotherapy recommendations support the principle of “deference to expertise,” where individuals with more experience or specialized knowledge are sought and valued. Further, HCPs’ contingency plans and creative use of back-up behaviors demonstrate the “commitment to resilience” principle. Some HCPs implemented multiple actions to increase the redundancy—and therefore the safety—of care delivery. HCPs’ previous experience with coordination challenges appeared to bring about their coordinating strategies, which were frequently intended to prevent future gaps in care. Underlying the high-reliability principles is a culture in which workers watch for, and address, unsafe conditions before they pose substantial risk.32 We found this culture among HCPs in our study.

Another novel finding was that pharmacists engaged in unique back-up behaviors to track the patient’s care and ensure medication safety of their own initiative, beyond their typical responsibilities. Pharmacists’ underlying goal was to confirm that patients received the intended care. The need for tracking was prompted by two factors. First, pharmacists make safety-critical recommendations, but due to their limited scope of authority, rely upon other HCPs to enact their recommendations. Second, pharmacists had previous experiences where their recommendations were not received or implemented. Thus, their “tracking” back-up strategy closes the loop in healthcare delivery by confirming a positive outcome. This coordinating goal warrants improved safety mechanisms (see Table 4.v) and should be formally supported and reimbursed as part of job responsibilities.

Role ambiguity was a barrier for physicians and pharmacists alike, and has been reported by other studies33,34 Ambiguity is likely to escalate as the complexity of care coordination increases, with patients receiving care from multiple provider types and institutions. This reflects coordination challenges associated with HCPs’ situation awareness35 of the patients’ clinical status and desire to forecast the future clinical state of the patient, which can become more difficult as knowledge of the patient is dispersed across HCPs.

Sometimes, heavy reliance on EHR communication exacerbated safety risks. EHR-related communication provided valuable information and, at other times, consternation as HCPs sought elusive EHR information from other providers. Arndt et al. stated, “Routing all communication among team members through the EHR adds layers of inefficiency and distracts the team from higher-quality verbal communication.”36 There is limited guidance on communication modalities to use for safety-related concerns in healthcare. Additionally, coordinating functions of EHRs in the USA are underdeveloped.37 Table 4 presents ideas, prompted by human factors analysis of our data, that might aid medication coordination and could be tested in future research.

This study has limitations. Aside from pilot testing, we did not conduct further validation research on the incident submission form; instead, our study clinicians screened submitted incidents for eligibility. HCPs accessed the EHR during interviews to aid their recollection of the incident,15 but many aspects of data collection relied on HCPs’ self-reported information that might not always be accurate. The retrospective study design may have introduced recall bias regarding HCPs’ interpretation of events. However, our results for role ambiguity and heavy EHR reliance for communication align with other literature,33,34,36 supporting the external validity of our findings. HCPs could complete multiple interviews; thus, their strategies may be overrepresented in the larger study, but we mitigated this by including only one interview per HCP in the care coordination analysis. Our sample did not include all possible categories of medication safety incidents, but we chose three common categories that pose high safety risks. Additionally, this analysis did not include nurses or nurse practitioners. They might use other strategies or encounter additional barriers and are also instrumental in medication safety. Comparing physicians and pharmacists, the only notable difference we identified was that pharmacists leveraged unique back-up behaviors. Incidents varied widely within each category (e.g., medications involved, patient characteristics), precluding nuanced analysis of differences by HCP type or level of experience, but differences could be evaluated in future research using simulation interviews with standardized incident scenarios.

Nevertheless, our results offer widespread insights since the overarching coordinating strategies and barriers were evident across physicians and pharmacists and occurred with all three incident categories. This indicates that barriers to care coordination are driven by system factors, and less by the specific HCP or type of medication incident.

In conclusion, this research provides novel insights into care coordination during medication safety incidents and delineates HCPs’ associated, medication-related coordinating strategies for the first time. Our study used a novel application of cognitive task analysis and our results demonstrate the benefits of this method for understanding complex decision-making. We found similar strategies and barriers across HCP groups and incident types, suggesting that our findings offer important insights into care coordination that may apply to a variety of HCPs and a wide range of medication safety incidents. HCPs’ coordinating strategies for medication incidents often aligned with high-reliability principles and should be encouraged by healthcare processes and administrators. There is a particular need to support pharmacists, who often went to extraordinary efforts to follow patients “behind the scenes,” to ensure intended medication safety actions were implemented by prescribers. Further efforts are warranted to enhance EHR designs for care coordination and to provide more formal guidance regarding the use of communication modalities for safety-critical events.

References

Medication Without Harm - Global Patient Safety Challenge on Medication Safety. Geneva, Switzerland: Geneva: World Health Organization, License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; 2017.

Lu CY, Roughead E. Determinants of patient-reported medication errors: a comparison among seven countries. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(7):733-740.

“About Medication Errors” by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error and Reporting and Prevention. https://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors. Accessed 4 Aug 2020.

Gates PJ, Baysari MT, Mumford V, et al. Standardising the Classification of Harm Associated with Medication Errors: The Harm Associated with Medication Error Classification (HAMEC). Drug Saf. 2019;42(8):931-939.

Boostani K, Noshad H, Farnood F, et al. Detection and Management of Common Medication Errors in Internal Medicine Wards: Impact on Medication Costs and Patient Care. Adv Pharm Bull. 2019;9(1):174-179.

Zhou S, Kang H, Yao B, et al. Analyzing Medication Error Reports in Clinical Settings: An Automated Pipeline Approach. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:1611-1620.

Tariq RA, Vashisht R, Scherbak Y. Medication Errors. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL); 2020.

McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. In: Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Publication No. 04(07)-0051-7; 2007.

Funk KA, Pestka DL, Roth McClurg MT, et al. Primary Care Providers Believe That Comprehensive Medication Management Improves Their Work-Life. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(4):462-473.

Lee CY, Goeman D, Beanland C, et al. Challenges and barriers associated with medication management for home nursing clients in Australia: a qualitative study combining the perspectives of community nurses, community pharmacists and GPs. Fam Pract. 2019;36(3):332-342.

Mickelson RS, Holden RJ. Medication management strategies used by older adults with heart failure: A systems-based analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(5):418-428.

Redmond P, Carroll H, Grimes T, et al. GPs’ and community pharmacists’ opinions on medication management at transitions of care in Ireland. Fam Pract. 2016;33(2):172-178.

Patel VL, Kannampallil TG, Shortliffe EH. Role of cognition in generating and mitigating clinical errors. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(7):468-474.

Patel VL, Cohen T, Murarka T, et al. Recovery at the edge of error: debunking the myth of the infallible expert. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(3):413-424.

Russ AL, Militello LG, Glassman PA, et al. Adapting Cognitive Task Analysis to Investigate Clinical Decision Making and Medication Safety Incidents. J Patient Saf. 2019;15(3):191-197.

Elkhadragy N, Ifeachor AP, Diiulio JB, et al. Medication decision-making for patients with renal insufficiency in inpatient and outpatient care at a US Veterans Affairs Medical Centre: a qualitative, cognitive task analysis. BMJ open. 2019;9(5):e027439.

Hoffman RR, Crandall B, Shadbolt N. Use of the Critical Decision Method to Elicit Expert Knowledge: A Case Study in the Methodology of Cognitive Task Analysis. Human Factors. 1998;40(2):254-276.

Crandall B, Klein G, Hoffman RR. Working Minds: A Practitioner’s Guide to Cognitive Task Analysis (A Bradford Book). Cambridge: MIT Press; 2006.

Hoffman RR, Militello LG. Perspectives on Cognitive Task Analysis: Historical Origins and Modern Communities of Practice. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2008.

Woolley A, Kostopoulou O. Clinical intuition in family medicine: more than first impressions. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):60-66.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-1251.

Friesen MA, White SV, Byers JF. Handoffs: Implications for Nurses. In: Hughes RG, ed. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD); 2008.

Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):148.

Militello LG, Klein G. Decision-centered design. The Oxford handbook of cognitive engineering. Vol Mar 72013.

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772.

Patterson ES, Cook RI, Render ML. Improving patient safety by identifying side effects from introducing bar coding in medication administration. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(5):540-553.

Slaughter L, Keselman A, Kushniruk A, et al. A framework for capturing the interactions between laypersons’ understanding of disease, information gathering behaviors, and actions taken during an epidemic. J Biomed Inform. 2005;38(4):298-313.

Russ AL, Zillich AJ, McManus MS, et al. Prescribers’ interactions with medication alerts at the point of prescribing: A multi-method, in situ investigation of the human-computer interaction. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(4):232-243.

Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115.

Klein G, Crandall BW. The role of mental simulation in problem solving and decision making. . In: Hancock PA, Flach JM, Caird J, Vicente KJ, eds. Local applications of the ecological approach to human-machine systems. Vol 2.1995:324-358.

Salas E, Wilson-Donnelly K, Sims DE, et al. Teamwork Training for Patient Safety: Best Practices and Guiding Principles. In: Carayon P, ed. Handbook on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2007:803-822.

Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. In: Evidence Brief: Implementation of High Reliability Organization Principles. Washington (DC); 2019.

Werner NE, Malkana S, Gurses AP, et al. Toward a process-level view of distributed healthcare tasks: Medication management as a case study. Appl Ergon. 2017;65:255-268.

To TP, Brien JA, Story DA. Barriers to managing medications appropriately when patients have restrictions on oral intake. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019.

Wright MC, Taekman JM, Endsley MR. Objective measures of situation awareness in a simulated medical environment. Quality & safety in health care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i65-71.

Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment Using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion Observations. Annals of family medicine. 2017;15(5):419-426.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Strategy on Reducing Regulatory and Administrative Burden Relating to the Use of Health IT and EHRs. Final Report, Feb 2020:1-73.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for making this work possible. Zamal Franks, Amy Brandt, Linda Collins, and Steven Sanchez assisted with IRB procedures. Ms. Donna Burgett, Regenstrief Institute, assisted with manuscript formatting. We presented a brief summary of our preliminary findings for the care coordination analysis at the American Medical Informatics Symposium in Chicago, IL, Nov 2016 and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service National Conference, Washington, DC, July 2017.

Contributors

ARJ wrote the funded grant proposal (VA HSR&D CDA 11-214), with input from PG and MW. RD assisted with IRB materials, participant recruitment, incident card collection, and demographic data analysis. All authors, except AI and CL, participated in study planning meetings and contributed to the design of the larger study. LM trained ARJ on cognitive task analysis and the critical incident technique. ARJ conducted all interviews. ARJ, KA, and AI analyzed interview transcripts to develop a decision requirements table for each incident. RD conducted the computerized randomization to select incidents for the care coordination analysis. RD and CL analyzed decision requirements tables from 24 incidents to identify emergent themes with respect to care coordination, under the mentorship of ARJ and KA. CL assisted with literature review and drafted an early version of the introduction. RD drafted the table of demographic information. ARJ drafted the rest of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and made important scientific edits to the manuscript and approved it for submission.

Funding

This work was supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award 11-214 (PI: ARJ) along with the Center for Health Information and Communication, Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, CIN 13-416 (PI: Weiner). Dr. Weiner is Chief of Health Services Research and Development at the Richard L. Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Indianapolis, IN. Manuscript writing was supported in part by VA IIR 16-297. Dr. Luckhurst was funded by the VA Postdoctoral Associated Health Fellowship Program in Medical Informatics, VA Office of Academic Affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

LM is co-owner of Applied Decision Science, LLC, a company that studies decision-making in complex environments and utilizes the critical decision method. She aided in the design of the cognitive task analysis approach used in this study and trained the interviewer. MW has stock in Allscripts and Express Scripts Holding Company. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data Sharing Statement

To preserve participant confidentiality, qualitative data sources (e.g., interview transcripts) from this study are not shared.

Disclaimer

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

We presented a brief summary of our preliminary findings at the 2016 American Medical Informatics Symposium and 2017 Veterans Affairs (VA) conference for health services research.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Russ-Jara, A.L., Luckhurst, C.L., Dismore, R.A. et al. Care Coordination Strategies and Barriers during Medication Safety Incidents: a Qualitative, Cognitive Task Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 2212–2220 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06386-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06386-w