Abstract

Background

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infected over 5 million United States (US) residents resulting in more than 180,000 deaths by August 2020. To mitigate transmission, most states ordered shelter-in-place orders in March and reopening strategies varied.

Objective

To estimate excess COVID-19 cases and deaths after reopening compared with trends prior to reopening for two groups of states: (1) states with an evidence-based reopening strategy, defined as reopening indoor dining after implementing a statewide mask mandate, and (2) states reopening indoor dining rooms before implementing a statewide mask mandate.

Design

Interrupted time series quasi-experimental study design applied to publicly available secondary data.

Participants

Fifty United States and the District of Columbia.

Interventions

Reopening indoor dining rooms before or after implementing a statewide mask mandate.

Main Measures

Outcomes included daily cumulative COVID-19 cases and deaths for each state.

Key Results

On average, the number of excess cases per 100,000 residents in states reopening without masks is ten times the number in states reopening with masks after 8 weeks (643.1 cases; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 406.9, 879.2 and 62.9 cases; CI = 12.6, 113.1, respectively). Excess cases after 6 weeks could have been reduced by 90% from 576,371 to 63,062 and excess deaths reduced by 80% from 22,851 to 4858 had states implemented mask mandates prior to reopening. Over 50,000 excess deaths were prevented within 6 weeks in 13 states that implemented mask mandates prior to reopening.

Conclusions

Additional mitigation measures such as mask use counteract the potential growth in COVID-19 cases and deaths due to reopening businesses. This study contributes to the growing evidence that mask usage is essential for mitigating community transmission of COVID-19. States should delay further reopening until mask mandates are fully implemented, and enforcement by local businesses will be critical for preventing potential future closures.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infected 5 million United States (US) residents resulting in more than 180,000 deaths by the end of August 2020.1 In an effort to mitigate COVID-19 infection rates in the US, states implemented social distancing policies including limiting the size of group gatherings, closing public schools and non-essential businesses, and shelter in place (lockdown) orders. Starting on April 30, state stay-at-home and shelter-in-place policies began to expire with all 50 states reopening non-essential businesses at some level by May 26, 2020.2 Evidence for the effect of reopening non-essential businesses on COVID-19 cases is needed to inform future mitigation strategies as the pandemic continues.

In the absence of therapeutics and contact tracing capacity, COVID-19 mitigation and suppression strategies in the US relied on social distancing policies to prevent the spread of the disease and reduce COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality. Policy makers have had to weigh the benefits of social distancing policies against the social and economic costs of social distancing measures.3 Studies have demonstrated the substantial effect state social distancing mandates had in limiting the spread of COVID-19 relative to projections without intervention.4, 5 However, the closure of non-essential businesses has also created stress on the economy, with unprecedented job loss leading to a recession.3 To stem these negative effects, states began to reopen, and public health agencies promoted the wearing of masks and other strategies to mitigate the spread.6

Knowledge about the novel virus and routes of transmission has evolved since the virus first appeared in the US, and the recent evidence suggests that dining on-site at restaurants might be an important risk factor associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.7 Growing consensus about the role of aerosols in transmission of the virus has led the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to change recommendations for mitigation measures. Airborne transmission is particularly effective in indoor, poorly ventilated areas, such as restaurants. Though public health authorities did not recommend widespread face mask use in public at the start of the pandemic, evidence demonstrating the role of asymptomatic transmission led to changes in recommendations for widespread mask use starting in early April.8 CDC guidance recommends people 2 years of age and older wear a mask in public areas and around people who do not live in the same household in addition to social distancing.9 States that began reopening strategies without opening indoor dining rooms is a signal that these states were implementing evidence-based strategies.

States reopening strategies varied widely, as did the use of evidence and data in reopening safely. Most states reopened in phases, stretching the reopening of restaurants, gyms, religious facilities, retail stores, hair salons, and bars over a period of weeks or months. During the lock downs, restaurants were generally permitted to provide food for take-out, and states implemented reopening restrictions such as outdoor seating only, limited capacity, spacing requirements, and masks. At the end of August 2020, the majority of states were failing to meet key criteria proposed by public health experts for reopening safely while mitigating community spread.10 Multiple states have had to return to more restrictive policies and close non-essential businesses due to the growth in COVID-19 cases after reopening.11 Policy makers need more information about the effects of reopening on the COVID-19 burden in each state, and how different reopening strategies impact transmission of the virus.

Our objective is to estimate the excess COVID-19 burden for two groups of states: (1) states with an evidence-based reopening strategy, defined as reopening indoor dining rooms after implementing a statewide masking policy, and (2) states lacking an evidence-based reopening strategy, defined as reopening indoor dining rooms before implementing a statewide masking policy. For each of these groups, our study design estimates the average change in the rate of growth in COVID-19 cases and deaths after reopening compared to before reopening. We use the reopening of indoor dining spaces to indicate a potentially unsafe level of reopening if criteria for low growth of COVID-19 cases are not met. We hypothesize that reopening will increase cases and deaths irrespective of reopening strategies, but we anticipate that the increase will be smaller among the group of states with the evidence-based approach. Additionally, we describe state reopening policies for each group and provide estimates of the impact in each state to inform state strategies for mitigating the spread of COVID-19.

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

Study Design

We used an interrupted time series (ITS) to compare the rate of growth in COVID-19 cases and deaths after reopening to growth prior to the reopening. Because all states reopened, each state serves as its own control.12 To estimate what the case rate would have been if the state had not reopened, we assume the state-specific trend in cases prior to reopening would have continued to be the same if the state had not reopened. State fixed effects controlled for state characteristics associated with outcomes that did not change over the study period. Our sample included 50 US states and the District of Columbia. Daily COVID-19 confirmed case counts were obtained from the New York Times database from January 21 through July 16, 2020.11 State population data were obtained from the 2018 American Community Survey.13 State reopening policy data was linked from the Boston University COVID-19 US State Policy database, with four corrections (see supplemental appendix).13

Intervention

Most states used a phased reopening strategy, and there was substantial variation in the implementation of reopening approaches across states. Thus, it was important to define a meaningful and specific level of reopening that would be expected to influence COVID-19 outcomes as the date of reopening in this study. We defined reopening as the date of reopening indoor dining rooms at any capacity, as most states initially opened indoor dining at limited capacity.11 Reopening indoor dining represented an earlier milestone among states’ various reopening policies, allowing for more accurate depiction of the effect of reopening, but was also associated with reasonable risk for COVID spread if implemented too early or poorly (i.e., restaurants did not follow guidelines for sanitation, table-spacing, or mask-wearing). If a state did not explicitly detail dining restrictions in their reopening policies (assessed using two sources), the expiration of shelter in place was used as the date of reopening.2, 11

We estimated excess COVID-19 burden for states reopening indoor dining after implementing a statewide mask mandate, also referred to as evidence-based reopening. We also estimated excess COVID-19 burden for states reopening prior to implementing a statewide mask mandate. The date of mask mandate was defined as a statewide order requiring masks for all adults in public spaces where social distancing is not maintained (with medical exceptions). For the 21 states that implemented a mask mandate after opening dining rooms, there was an average of 56 days between the date of reopening dining rooms and the date of the mask mandate. Thus, our 56-day follow-up period and estimated effects primarily occur prior to subsequent mask mandates.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the daily cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in the state. The outcome was lagged by 5 days because the effect of the intervention on cases was expected to be delayed by the incubation period as well as reporting time. A shorter lag time was preferred to avoid classifying daily outcomes from the post-period in the pre-period, and prior evidence suggested that effects are significant as early as 5 days after implementation.6 The secondary outcome was cumulative COVID-19 deaths, lagged by 10 days.

Statistical Analysis

We predicted cumulative daily cases and deaths using generalized linear models with a negative binomial distribution and a log link. For all models, we used an offset for the log of the total population in each state to account for varying population sizes and present marginal effects as a rate per 100,000 residents. The time variable was centered around the date of reopening for each state. The period was truncated at 40 days prior to reopening to improve estimates of state trends prior to reopening and reduce bias due to periods of zero growth early in the epidemic. Testing capacity prior to reopening is controlled for using the state-specific trends in observed cases prior to the intervention. While random variation in testing capacity across states over time is expected, this fluctuation would not bias our estimates unless testing capacity were systematically different after reopening compared to the baseline period. We used robust standard errors to account for heteroscedasticity in measurement of cases over time and clustered standard errors by day to address temporal clustering, such as from changes in testing capacity over time.

To improve model fit, we tested higher order terms and alternative distribution assumptions. After selecting the best-fitting model using the Akaike information criterion, models estimated time trends for each state by interacting the state indicator with a linear, quadratic, and cubic time trend (see statistical appendix). The effects of reopening with and without a mask mandate (compared to the pre-trends within each group) were estimated using an interaction of the indicator for the post-period, treatment group (pre-opening, reopening with masks, reopening without masks), and the time trend. The quadratic time trend was interacted with the post-period indicator.

State-specific estimates for excess cases and deaths were generated using the method of recycled predictions. For each state, we compared the predicted outcomes for that state under two scenarios (opening with masks and opening without masks) using the original model estimates. The total treatment effect includes the linear and quadratic changes in trends. To generate the predictions, we applied the state’s specific fixed effect and baseline trends as estimated in the original model (different for each state) and the estimated average treatment effect (the estimated change in trends after reopening compared to before). We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results, including different lag times for the outcome. We ran models with and without New York and New Jersey included because of the large case counts that skew average marginal effects. The conclusions were robust to all robustness checks (statistical appendix). All analyses were conducted using Stata 16.0.

RESULTS

Of 50 states and the District of Columbia, 13 states (CT, DE, DC, IL, ME, MD, MA, MI, NJ, NM, NY, PA, RI), most in the North East Census Region, had implemented a statewide mask mandate before opening indoor dining rooms, referred to as evidence-based opening (Table 1). The median opening date among states with evidence-based reopening strategies was 40 days later than the median in the rest of states, June 10 compared to May 1, 2020. The evidence-based group also had experienced greater cumulative COVID-19 burden of cases and deaths per capita on the date of reopening. Of the 38 states opening dining rooms prior to implementing a statewide mask mandate, only 21 implemented a statewide mask mandate as of August 31, on average 56 days following indoor restaurant reopening. The evidence-based group was less likely to open bars, gyms, salons, religious facilities, retail stores, theaters, and to allow non-essential medical procedures.

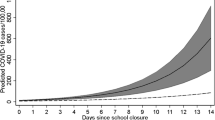

Among states that reopened indoor dining prior to a statewide mask mandate, the estimated daily growth rate for cumulative COVID-19 cases increased after reopening compared with before reopening (Fig. 1) (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.017; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.011, 1.024). The states reopening with mask mandates had a much smaller increase in growth after reopening compared to before (IRR = 1.003; CI = 1.001, 1.006) (Fig. 2). Similarly, daily growth in deaths increased more among states reopening without a statewide mask mandate compared to states with mask mandates (IIR = 1.017; CI = 1.012, 1.023; and IRR = 1.005; CI = 1.003, 1.007, respectively) (Fig. 3).

The change in rate of growth causes exponential increases in excess cases over a period of 8 weeks. On average, the number of excess cases per 100,000 residents in states reopening without masks was ten times the number in states reopening with masks after 8 weeks (643.1 cases; CI = 406.9, 879.2; and 62.9 cases; CI = 12.6, 113.1, respectively) (Table 2). On average, the number of excess deaths per 100,000 residents in states reopening without masks is five times the number in states reopening with masks after 8 weeks (31.7 deaths; CI = 20.8, 42.5; and 6.1 deaths; CI = 3.5, 8.7, respectively) (Table 2).

After 6 weeks, reopening without a mask mandate compared to not reopening resulted in 576,371 excess COVID-19 cases and 22,851 excess COVID-19 deaths among 38 states (Table 3). Applying the estimated effect of reopening with masks, we calculate that the excess cases could have been reduced by nearly 90% to 63,062 had these states delayed reopening indoor dining rooms until mask mandates were implemented. Among the 13 states reopening with mask mandates, we estimate 105,652 excess cases and 14,660 excess deaths were due to reopening. Applying the estimated effect of reopening without masks, we estimate an additional 68,955 excess deaths would have occurred had reopening occurred prior to the mask mandates. Thus, over 50,000 excess deaths were prevented in 13 states.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluates the average effect of reopening indoor dining rooms for states that previously implemented a statewide mask mandate and for states that had not yet implemented a statewide mask mandate. The increase in cases in states opening indoor dining prior to a statewide mask mandate resulted in ten times more cases than the increase in states opening after implementing a mask mandate. We estimate approximately a half a million cases in 38 states could have been prevented by using evidence-based reopening strategies including delayed reopening of multiple business sectors and mask mandates. Although excess cases and deaths were observed following reopening in all states, an estimated 50,000 deaths were prevented in the 13 states that implemented evidence-based reopening by opening indoor dining rooms after mask orders were established.

This may be the first study to evaluate state variation in the effect of reopening on COVID-19 cases and deaths, and particularly estimating effects in states implementing evidence-based approaches such as mask mandates. We used the timing of states’ reopening of indoor dining as the measure of reopening given that these decisions came earlier in the trajectory of states’ reopening policies, and indoor dining presents heightened risk for COVID transmission if implemented poorly. These results are consistent with simulation models projecting a rebound in COVID-19 incidence and deaths in the month after states begin to reopen.14, 15 The estimated increase in cases and deaths due to reopening is only a fraction of the dramatic reduction in cases and mortality observed as a result of the shelter-in-place orders. Shelter-in-place orders and closures reductions in COVID-19 cases and deaths (decreased growth rate 15.4% and 11.6%) associated with the closure prevented nearly 33–34 million cases nationwide.4, 16

States implementing mask mandates were successful in minimizing the negative impacts of reopening, which is an encouraging signal for the return to indoor, on-site services in public schools and places of worship. While masking policy was a key difference between groups, there were many differences in other policies that would contribute to the effect, such as delayed reopening of bars and salons. Previous work demonstrates the substantial effect of mask policies on coronavirus cases, potentially averting close to a half a million COVID-19 cases.6 States that reopened under conditions of low community spread were likely to have smaller numbers of cases and deaths in the weeks following reopening. However, mortality may be higher in rural states since older and rural residents are likely to experience greater burden of serious illness and mortality due to COVID-19.17

Our results may be impacted by measurement error in the outcomes, as asymptomatic cases and out-of-hospital deaths are likely to be underrepresented. In addition, the state-level data do not capture the variation in local policies, which may have contributed to the impact of reopening. This study employs an intent-to-treat definition of reopening, and the actual behavior and adherence to the shelter-in-place and social distancing mandates both before and after reopening may bias results in either direction. In other words, our estimates represent an average effect of states’ reopening policies given the variation within and among states. Finally, we used the reopening date of indoor dining at restaurants as a proxy for a level of reopening that would meaningfully impact outcomes, and there is variation in the level of reopening across the states that may dilute the detectable effect of reopening and bias our results towards the null.

Estimating the average treatment effect across all 50 states improves the generalizability of our results compared to studies in single states or cities. Our results reflect the average effect across all states in each group. Our model was strengthened by the inclusion of state fixed effects to control for unique mix of policies in each state prior to reopening, such as effectiveness of the shelter-in-place orders and other mitigation strategies. This model can predict effect estimates specific to each state based on their unique trajectory prior to the intervention. As a result, these results are particularly valuable to state decision-makers seeking estimates specific to each state.

CONCLUSION

Reopening non-essential businesses, and in particular, indoor dining at restaurants, resulted in excess COVID-19 cases and deaths across the US; however, the increase was reduced by up to 90% in states implementing a statewide mask mandate prior to reopening restaurants for indoor dining. Additional mitigation measures such as face mask use are necessary to counteract the potential growth in COVID-19 cases and deaths as businesses reopen. This study contributes to the growing evidence that mask usage is essential for mitigating community transmission of COVID-19. States should delay further reopening until mask mandates are fully implemented, and enforcement by local businesses will be critical for preventing future closure of non-essential businesses.

Change history

09 November 2020

In the original version of this paper, an author was misidentified. The corrected author listing appears here, and has been updated in the online version.

References

New York Times. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nytimes/covid-19-data/master/us-counties.csv

Where States are Reopening After America's Shutdown. Washington Post. Accessed May 26, 2020, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/states-reopening-coronavirus-map/

Kochhar R. Unemployment rose higher in three months of COVID-19 than it did in two years of the Great Recession. Pew Research Center. Accessed Jul 7, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/11/unemployment-rose-higher-in-three-months-of-covid-19-than-it-did-in-two-years-of-the-great-recession/

Courtemanche C, Garuccio J, Le A, Pinkston J, Yelowitz A. Strong Social Distancing Measures In The United States Reduced The COVID-19 Growth Rate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1419-1425. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818

Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, et al. Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. 2020. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-03-16-COVID19-Report-9.pdf

Lyu W, Wehby GL. Community Use Of Face Masks And COVID-19: Evidence From A Natural Experiment Of State Mandates In The US. research-article. 2020-06-16 2020; https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818

Fisher KA. IVY Network Investigators, CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Community and Close Contact Exposures Associated with COVID-19 Among Symptomatic Adults ≥18 Years in 11 Outpatient Health Care Facilities — United States, July 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(36):6.

Woodruff J, Santhanam L, Thoet A. What Dr. Fauci wants you to know about face masks and staying home as virus spreads. Public Broadcasting Services. Accessed Sept 2, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/what-dr-fauci-wants-you-to-know-about-face-masks-and-staying-home-as-virus-spreads

Considerations for Wearing Masks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed Sept 2, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

Margolis Center for Health Policy. Tracking our COVID-19 Response. Accessed Sept 1, 2020. https://www.covidexitstrategy.org/

Lee JC, Mervosh S, Avila Y, Harvey B, Matthews AL. See how all 50 states are reopening (and closing again). New York Times. Accessed Sept 1 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html

Kontopantelis E, Doran T, Springate DA, Buchan I, Reeves D. Regression based quasi-experimental approach when randomisation is not an option: interrupted time series analysis. Bmj. 2015;350:h2750. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2750

Raifman J, Nocka K, Jones D, et al. COVID-19 US state policy database. Accessed May 26, 2020. www.tinyurl.com/statepolicies 6 https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets

Yamana T, Pei S, Kandula S, Shaman J. Projection of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US as Individual States Re-open May 4,2020. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Updated 2020-05-13. Accessed Jul 7, 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.04.20090670v2

Pham H. Predictive Modeling on the Number of Covid-19 Death Toll in the United States Considering the Effects of Coronavirus-Related Changes and Covid-19 Recovered Cases. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Updated 2020-06-17. Accessed Jul 7, 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.15.20132357v1

Kaufman BG, Whitaker R, Lederer NM, et al. State Variation in Effects of Non-Essential Business and Public School Closure on COVID-19 Cases. Pre-Publication. 2020.

Kaufman BG, Whitaker R, Pink G, Holmes GM. Half of Rural Residents at High Risk of Serious Illness Due to COVID-19, Creating Stress on Rural Hospitals. J Rural Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12481

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeremy Yi and Sophie Hurewitz for supporting data collection for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BGK made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article, and gave final approval of the version to be submitted. RW made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, and drafting the article, and gave final approval of the version to be submitted. NM made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, and revising the draft critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and any revised version. VS made substantial contributions to analysis design, interpretation of data, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be submitted. MBM made substantial contributions to analysis design, interpretation of data, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

BGK, RW, VS, and NM have no conflicts to disclose. Mark B. McClellan, MD, PhD, is an independent board member on the boards of Johnson & Johnson, Cigna, Alignment Healthcare, and Seer; co-chairs the CEO Forum for the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network; and receives fees for serving as an advisor to Blackstone Life Sciences, Coda, and Mitre.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 530 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaufman, B.G., Whitaker, R., Mahendraratnam, N. et al. Comparing Associations of State Reopening Strategies with COVID-19 Burden. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 3627–3634 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06277-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06277-0