Abstract

Background

Innovations and improvements in care delivery are often not spread across all settings that would benefit from their uptake. Scale-up and spread efforts are deliberate efforts to increase the impact of innovations successfully tested in pilot projects so as to benefit more people. The final stages of scale-up and spread initiatives must contend with reaching hard-to-engage sites.

Objective

To describe the process of scale-up and spread initiatives, with a focus on hard-to-engage sites and strategies to approach them.

Design

Qualitative content analysis of systematically identified literature and key informant interviews.

Participants

Leads from large magnitude scale-up and spread projects.

Approach

We conducted a systematic literature search on large magnitude scale-up and spread and interviews with eight project leads, who shared their perspectives on strategies to scale-up and spread clinical and administrative practices across healthcare systems, focusing on hard-to-engage sites. We synthesized these data using content analysis.

Key Results

Searches identified 1919 titles, of which 52 articles were included. Thirty-four discussed general scale-up and spread strategies, 11 described hard-to-engage sites, and 7 discussed strategies for hard-to-engage sites. These included publications were combined with interview findings to describe a fourth phase of the national scale-up and spread process, common challenges for spreading to hard-to-engage sites, and potential benefits of working with hard-to-engage sites, as well as useful strategies for working with hard-to-engage sites.

Conclusions

We identified scant published evidence that describes strategies for reaching hard-to-engage sites. The sparse data we identified aligned with key informant accounts. Future work could focus on better documentation of the later stages of spread efforts, including specific tailoring of approaches and strategies used with hard-to-engage sites. Spread efforts should include a “flexible, tailored approach” for this highly variable group, especially as implementation science is looking to expand its impact in routine care settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Moving research insights into clinical practice can be slow and a gap often remains between best practices, frequently developed within single sites or small populations, and care delivered at a population scale.1,2,3,4,5,6 The field of implementation science seeks to mend this gap by promoting the adoption and appropriate use of effective interventions, practices, policies, and programs in routine healthcare and public health settings.7,8,9,10 One growing facet within this large, interdisciplinary field is the study of scale-up and spread of innovations.8, 11,12,13 The terms “scale-up” and “spread” are not well-differentiated and often used together or interchangeably.8, 14 An exemplar definition describes scale-up and spread as “deliberate efforts to increase the impact of innovations successfully tested in pilot or experimental projects so as to benefit more people and to foster policy and program development on a lasting basis.”8, 15 This example exhibits typical components of scale or spread definitions, including the pre-established effectiveness of the innovation; the expansion across systems, sites, or settings; and the intentional process or active effort involved.1, 8, 12, 14, 16

Numerous frameworks and models have been developed for scale-up and spread,1,2,3,4, 9, 14, 17,18,19,20 with a recent review identifying 24 concepts, theories, or models in the public health sector alone.16 Here we focus on 2 widely used frameworks that describe the process of multisite scale-up and spread: the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s phases of scale-up1 and the QUERI pipeline.21 These frameworks follow three similar steps in the spread process: piloting and initial testing of some idea or innovation, small-scale test of spread strategies scale-up, and full scale-up or spread. Whether the earliest stage includes using an evidence-based innovation21 or developing a new idea,1 the first phase includes small-scale testing or piloting with direct involvement of the team at the initial site or small number of sites. This work requires personalized, first-hand contact and typically builds relationships among those developing, implementing, and evaluating the initiative. After initial testing, the regional roll-out phase allows for small-scale test of implementation strategies22 for scale-up or spread strategies before scaling up and/or spreading more broadly.

In both frameworks, the third phase, “going full-scale”1 or “national roll-out effort”,23 describes an effort that includes many organizations. Both frameworks present this final phase as a single phase, but both theory and evidence suggest that at the end of this phase some sites may be harder to engage.24,25,26 These late and non-adopters are typically not the focus of work published in this area;27 however, as efforts to expand the reach of scale-up and spread efforts grow, these sites will often be the final hurdle with which spread initiators will need to contend. We will be using the term “hard-to-engage” as a generic term to describe the group of organizations that scale-up and spread efforts have struggled to reach. This may include low performers, but these two groups are not synonymous as much as highly overlapping. As consolidations and mergers result in healthcare systems with more sites and expansive geographic boundaries, lessons about scale-up and spread from the Veterans Health Administration (VA), the largest nationwide system, become especially relevant.

The objective of this study is to describe the process of large magnitude scale-up and spread, including strategies available to scale-up and spread clinical and administrative practices across large healthcare systems, with a focus on hard-to-engage sites. Since there is a lack of information about how to tailor approaches to these hard-to-engage sites, our study explored the commonalities or characteristics of hard-to-engage sites to ascertain how these characteristics may aid or impede the spread process and explored the various strategies that have been used with hard-to-engage sites.

METHODS

The original report commissioned by the Department of Veterans Affairs,28 of which this work is one part, was intended to inform ongoing national spread efforts grappling with their approach to reaching hard-to-engage sites. Given the likely paucity of literature directly addressing strategies available to scale-up and spread clinical and administrative practices—both generally and with a focus on hard-to-engage sites—we planned our approach to use a systematic search to identify literature and then augmented this with semistructured interviews to collect relevant data. We then synthesized these two data sources using content analysis.29

Literature Searches

We searched multiple databases using key terms related to scaling or spread of health interventions, improving low-performing organizations, and learning health system(s). Our searches included the following databases: PubMed (inception to January 3, 2018), WorldCat (inception to January 10, 2018), Web of Science (inception to January 3, 2018), Business Source Complete (inception to November 21, 2017), SCOPUS (inception to January 10, 2018), and ROCS. We also searched for similar articles for 5 key publications.12, 30,31,32,33 See full search strategy in the ESM—Appendix A. In addition, we accessed the VA Assessment and Research Reporting Tool through 2017, a national database that supports administrative processes and reporting capabilities for a variety of VA research data, to find any publications affiliated with VA research projects. These publications were included in all screening and abstraction procedures.

Literature Selection and Data Abstraction

Three reviewers independently screened the titles of retrieved citations. For citations deemed relevant by at least one person, abstracts were screened independently in duplicate. Full-text review and data abstraction was conducted independently in duplicate, with all disagreements resolved through discussion. Studies were excluded at either the abstract or the full-text level if they were not about a healthcare delivery system, about low-income country settings, about learning healthcare systems but not spread, only discussed spread conceptually, or included fewer than 10 sites in the spread effort, since these would be describing the first two phases of scale-up and spread efforts, rather than a “national roll-out effort.”23

For each included publication, we abstracted data on the following: the rationale for starting the spread effort, focus/topic area of the practice or initiative, where spread occurred, if and how the publication described working with hard-to-engage sites, and magnitude of spread.

Key Informant Interview Sampling and Data Collection

In order to conduct interviews concurrently with the literature review process, we used a database with detailed project activity descriptions of all projects funded by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) programs from fiscal years 2008 to 2012 to identify a purposeful sample of interviewees.10 We identified 35 projects, from a total of 82, that described scale-up or spread activities. Of these, 11 projects described conducting national, multiregional, or multisite spread as part of the scope of the project; 14 projects described evaluations of national policy or program spread efforts; and 10 projects described analyses or work with low-performing sites. We identified the most relevant projects based on their size and any specific references to spread activities being analyzed or implemented. We selected the 2 national spread projects, 2 additional multisite/multiregion projects, 3 evaluation projects, and one analysis of low-performing sites. Key informants from all 8 of the projects were contacted via email and agreed to be interviewed by phone, and they shared their perspectives on and experiences with strategies to scale-up and spread clinical and administrative practices across healthcare systems, with a focus on “hard-to-reach” sites.

The interview guide (ESM—Appendix B) was developed to focus on areas that were described in less detail in the literature, in order to have complimentary data to that from the literature. The semistructured interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, ranging in duration from 26 to 53 min.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We first analyzed the literature and interview data separately, and then synthesized across these data sources using content analysis.29, 34 We built our analytic frame from existing frameworks and literature on scale-up and spread and identified extensions as these processes relate to hard-to-engage sites, drawing primarily on matrix analysis approach35, 36 which permits detailed cross-case analysis 35, 36. Based on our interview guide, we developed a template to rapidly organize data by interview questions.37 Each interview was coded by 3 members of the team, and consistency of interpretation was regularly maintained through team discussion.

RESULTS

We identified 1919 potentially relevant citations, of which 52 publications were included in this review (Fig. 1). The included publications discussed specific spread strategies for hard-to-engage sites (n = 7), described hard-to-engage sites but did not discuss specific strategies (n = 11), and discussed spread strategies more generally (n = 34). Table 1 includes more details about the included publications.

Breaking Down the National Scale-Up or Spread Process

The literature and interview data supported the descriptions of scale-up and spread proposed by the QUERI pipeline21 and IHI phases of scale-up1 in the first two phases, but our data split the final phase of “going full-scale”1 or “national roll-out effort”23 into two parts with distinct strategies which we describe as “mass broadcast” and “re-personalization” (see Fig. 2).

Mass Broadcast

The first part of the full-scale spread, which we are calling the “mass broadcast” phase, uses strategies intended to reach maximal audience. This first part seems to align with descriptions from the frameworks.1, 23

In publications and interviews alike, this phase was nearly always described as beginning with strong top-down support:

“…having a strong partnership with [national leaders] was a critical factor in making this happen and getting the facilities involved because they knew that we had the backing of the National Program Office.”

This top-down support could take the form of summits with all top-level leadership, for example: “… senior regional leadership identified reducing sepsis mortality as a key performance improvement goal… The effort was launched… at a Sepsis Summit.”38 Other more formal arrangements like an official mandate or policy change were also used, with mandates present cited in nearly every interview. This top-down support was typically effective during the “mass broadcast” phase of national spread efforts.

Re-personalization

The second part of full-scale spread, which we are calling the “re-personalization” phase, is focused on hard-to-engage sites that did not engage at the “mass broadcast” stage. The strategies recommended for hard-to-engage sites reflect a return to a more personalized approach, which uses more direct connection akin to what is typical in the first two phases of scale-up and spread. Early in the spread process, when experimenting with and testing strategies, spread initiators usually engage sites to collect data, refine approaches, and learn from experiences.

Considerations and Strategies for Working with Hard-to-Engage Sites

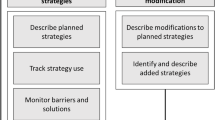

We drew from interviews and from the 18 publications we identified as either providing descriptions of hard-to-engage sites only (n = 11) or additionally providing descriptions of strategies used with these hard-to-engage sites (n = 7). Interviewees and publications alike supported the highly context-specific nature of challenges faced by hard-to-engage sites, whose “problems vary tremendously” with a “myriad of individual reasons,” according to interviewees. The phrase “N-of-1” was used repeatedly by interviewees to describe experiences working with hard-to-engage sites. Since hard-to-engage sites are highly variable in their needs, interviewees recommended “a flexible, tailored approach to one [site] at a time.” Drawing from both interviews and literature, we describe useful strategies to address these common challenges and maximize potential benefits (Fig. 3).

Common Challenges for Spreading to Hard-to-Engage Sites and Strategies for Addressing Them

Certain challenges arise that spread initiators or sites themselves may face when working with hard-to-engage sites (see Table 2). Spread initiators described a variety of approaches tailored to hard-to-engage sites that faced common challenges (see Table 3).

Limited bandwidth or resources, such as turnover and lack of funding, burnout, or implementation as an added duty without additional compensation,39 were common in hard-to-engage sites. No system or model of spread seemed to be immune, as “lack of resources” was frequently mentioned as a factor impeding spread.49 One strategy spread initiators used for hard-to-engage sites with limited resources was external facilitation,40, 41 which provides additional supports to those sites with low bandwidth, or who may need extra support for other reasons. Working with multiple local people reduces the burden on any individual and strengthens overall linkages to that site for a spread initiative. This strategy provides a “web of support,” as one interviewee called it.

Local innovations or homegrown solutions to the same problem can present competition that impedes spread, since “there was no expressed need for the program.”42 Two strategies to mitigate this challenge are (1) peer-to-peer communication, where individuals share information and receive support from fellow spread initiative participants, particularly from individuals of the same “rank” or “level”, and (2) to allow local sites to “kick the tires” of the innovation, which gives sites a chance to test the innovation and provide feedback prior to implementation (i.e., “trialability”).24

Potential spread sites were often very busy addressing local priorities that may not overlap with the aims of a particular spread initiative. Although competing priorities can impede scale-up and spread, tackling upstream issues, such as pre-existing information technology infrastructure gaps, and increasing visibility with multiple levels of leadership can help protect the initiative and demonstrate success for those sites involved.

Potential Benefits of Working with Hard-to-Engage Sites and Strategies to Maximize Them

Spread initiators identified several ways that they perceived hard-to-engage sites would view participating in spread initiative as beneficial, and, while slower to start, these sites reaped unique benefits for themselves (see Table 2). In working with hard-to-engage sites, spread initiators described using a few strategies that maximized engagement and, in turn, potential benefits (see Table 3).

Interviewees described situations where “healthy skepticism” led to collaboration and, in some cases, improvement of the practice or initiative being spread. Taking advantage of a “hard core and a soft periphery”43 model of intervention, where the core model is adaptable to a local context, may help realize local compatibility and fit needs that may differ from sites where the intervention was originally tested.

Some spread initiators chose to “take the long view” with the scale-up and spread process. They noted that once some hard-to-engage sites are engaged, their hard-won adoption could lead to more sustainable successes in the long-term, in contrast with early adoption which could lead to superficial engagement and, consequently, abandonment. For these long-term wins, spread initiators maintained engagement and gave opportunities for slower adopters to build commitment and find avenues to adoption within their local contexts.

There is added incentive for sites to participate in a spread initiative when goals of spread efforts align with the needs of hard-to-engage sites. In framing the pitch, establishing rapport with hard-to-engage sites early in the process by conducting in-person initial visits could help with spread initiative. Interviewees consistently described focusing on “being seen” as helpful, rather than punitive or authoritarian action.

DISCUSSION

Using content analysis of literature and key informant interviews, we described four phases of scale-up and spread, the first two aligning with descriptions presented in QUERI and IHI frameworks. We suggest that rather than one more phase of a “national roll-out effort,”23 there is a third phase, mass broadcast, in which strategies are used to reach maximal audience, and a fourth phase, re-personalization, marked by a return to using strategies more often employed in the early phases of the spread process. While descriptions of hard-to-engage sites often portrayed challenges, a number of beneficial characteristics were also depicted. Hard-to-engage sites can be highly variable in terms of the challenges or barriers they face. Since hard-to-engage sites are heterogeneous in their needs, interviewees recommended “a flexible, tailored approach to one [site] at a time.”

While many frameworks and models exist that outline scale-up and spread in a general way, scant published evidence has been identified that provides discussion of strategies for reaching sites that are hard-to-engage. Those publications that did mention hard-to-engage sites spent a few sentences, at most, discussing the topic. The sparse data identified from the literature aligned with key informant accounts, which allowed us to differentiate this last group in a fourth phase. This finding expands on prior discussions of scale-up and spread and is hypothesis generating, and while some promising new work is underway,44 more studies focused in this area are needed. Additional exploratory studies could determine if there is consistent representation of these concepts in scale-up and spread efforts, and better documentation of the later stages of spread efforts, including specific strategies and/or adaptations used to engage hard-to-engage sites, is needed.

Because terminology related to scale and spread is evolving, there are no reliable, standardized terms for systematically searching for literature related to this topic, so relevant literature might have been missed. In addition, studies that have conducted large magnitude scale initiatives do not always describe their experiences with or strategies for engaging hard-to-engage sites. We also do not have information about the contexts or success of unpublished spread efforts, of which there are likely many, given that spread and scale-up happens regularly in nonresearch settings. While interviews give a depth of information, we were not able to gather that detailed data for all initiatives identified in the literature synthesis portion of the study. While other initiatives, particularly those outside the VA, may have different experiences to report, the data we did have aligned well, independent of setting. In addition, we limited our scope to scale-up and spread in healthcare settings, given that the nature of initiatives in healthcare settings tend to be complex, which mirrors the complexity of the services provided in healthcare settings compared to other industries. Additionally, healthcare organizations tend to be very large, have many layers of hierarchy and authority, and be subject to unique regulation and policy pressures and other factors that make scale-up and spread efforts in this field unique. However, spread in other nonhealthcare settings could potentially inform healthcare spread, and our current scope would not have included these potentially relevant experiences.

If implementation science is to expand its impact in routine care settings, more testing of scale-up and spread strategies, as well as documentation of adaptations or tailoring, is needed. Hard-to-engage audiences are most in need of engagement when spreading innovations intended to standardize practice or improve quality of care, but they are understudied. Ameliorating variations in care delivery will require a better understanding of how to work with hard-to-engage groups. For the myriad of individual factors these sites face, bundles of engagement strategies that are more personalized and intensive seem to help spread initiators reach these groups, but determining which strategies work well in different situations will require additional empirical work.

References

Simmons R, Fajans P, Ghiron L. Scaling up health services delivery: From pilot innovations to policies and programmes. World Health Organization;2008.

OVretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, et al. Quality collaboratives: lessons from research. Quality & safety in health care. 2002;11(4):345-351.

Nolan K, Schall MW, Erb F, Nolan T. Using a framework for spread: The case of patient access in the Veterans Health Administration. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2005;31(6):339-347.

McCannon CJ, Berwick DM, Massoud MR. The science of large-scale change in global health. Jama. 2007;298(16):1937-1939.

World Health Organization. Bridging the “know–do” gap meeting on knowledge translation in global health. Geneva: WHO;2006.

In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Owens DK, eds. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 1: Series Overview and Methodology). Rockville (MD)2004.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32.

Norton WE, McCannon C, Schall MW, Mittman BS. A stakeholder-driven agenda for advancing the science and practice of scale-up and spread in health. [Internet Resource; Article]. 2012; http://www.implementationscience.com/content/7/1/118

Simmons RS, J. Scaling up health service innovations: a framework for action. Scaling up health service delivery. 2007;1(30).

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis. In Mixed Method Implementation Research. Administration and policy in mental health. 2015;42(5):533-544.

Berwick D. The science of improvement. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(10):1182-1184.

Aarons GA, Sklar M, Mustanski B, Benbow N, Brown CH. "Scaling-out" evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems. Implementation science : IS. 2017;12(1):111.

About Implementation Science (IS). 2018; https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/about.html.

Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, Taylor BS, et al. How complexity science can inform scale-up and spread in health care: understanding the role of self-organization in variation across local contexts. Social science & medicine (1982). 2013;93:194-202.

ExpandNet. Scaling-up Framework. 2019; https://expandnet.net/scaling-up-framework-and-principles/.

Milat AJ, Bauman A, Redman S. Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implementation science : IS. 2015;10:113.

McCannon CJ, Schall MW, Perla RJ. Planning for scale: A guide for designing large-scale improvement initiatives. 2008.

McCannon CJ, Perla RJ. Learning networks for sustainable, large-scale improvement. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2009;35(5):286-291.

Massoud MR, Nielsen GA, Nolan K, et al. A Framework for Spread: From Local Improvements to System-Wide Change. IHI Innovation Series White Paper Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2006.

Subramanian S, Naimoli J, Matsubayashi T, Peters DH. Do we have the right models for scaling up health services to achieve the Millennium Development Goals? BMC health services research. 2011;11:336.

Stetler CB, Mittman BS, Francis J. Overview of the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) and QUERI theme articles: QUERI Series. Implementation science : IS. 2008;3:8.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation science : IS. 2015;10:21.

Asch SM, Kerr EA. Measuring What Matters in Health: Lessons from the Veterans Health Administration State of the Art Conference. Journal of general internal medicine. 2016;31 Suppl 1:1-2.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. Simon and Schuster; 2010.

Patel H, Wilson E, Vizzotti C, et al. Argentina's Successful Implementation Of A National Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Program. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2016;35(2):301-308.

Lustig A, Ogden M, Brenner RW, et al. The Central Role of Physician Leadership for Driving Change in Value-Based Care Environments. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy. 2016;22(10):1116-1122.

Robert G, Morrow E, Maben J, et al. The adoption, local implementation and assimilation into routine nursing practice of a national quality improvement programme: the Productive Ward in England. Journal of clinical nursing. 2011;20(7-8):1196-1207.

Miake-Lye IM, Mak S, Lambert-Kerzner AC, et al. Scaling Beyond Early Adopters: A Systematic Review and Key Informant Perspectives. Washington D.C.: Department of Veterans Affairs;2019.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277-1288.

Grumbach K, Lucey CR, Johnston SC. Transforming from centers of learning to learning health systems: the challenge for academic health centers. Jama. 2014;311(11):1109-1110.

Lowes LP, Noritz GH, Newmeyer A, et al. Learn From Every Patient: implementation and early results of a learning health system. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2016.

Smoyer WE, Embi PJ, Moffatt-Bruce S. Creating Local Learning Health Systems: Think Globally, Act Locally. Jama. 2016;316(23):2481-2482.

Yano EM, Green LW, Glanz K, et al. Implementation and spread of interventions into the multilevel context of routine practice and policy: implications for the cancer care continuum. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2012;2012(44):86-99.

Potter WJ, Levine-Donnerstein D. Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 1999;27(3):258-284.

Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative health research. 2002;12(6):855-866.

Miles MB, Hubeman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2014.

Hamilton A. Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn-Around Health Services Research. VA HSR&D National Cyberseminar Series: Spotlight on Women’s Health; 2013.

Liu VX, Morehouse JW, Baker JM, et al. Data that drive: Closing the loop in the learning hospital system. Journal of hospital medicine. 2016;11 Suppl 1:S11-s17.

Lorig KR, Hurwicz ML, Sobel D, et al. A national dissemination of an evidence-based self-management program: a process evaluation study. Patient education and counseling. 2005;59(1):69-79.

Heinrich J. Cultural transmission and the diffusion of innovations: Adoption dynamics indicate that biased cultural transmission is the predominate force in behavioral change. American Antrhopologist. 2001;103(4):992-1013.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank quarterly. 2004;82(4):581-629.

Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implementation science : IS. 2013;8:51.

Denis JL, Hebert Y, Langley A, et al. Explaining diffusion patterns for complex health care innovations. Health care management review. 2002;27(3):60-73.

Hagedorn H, Kenny M, Gordon A, et al. Advancing pharmacological treatments for opioid use disorder (ADaPT-OUD): protocol for testing a novel strategy to improve implementation of medication-assisted treatment for veterans with opioid use disorders in low-performing facilities. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2018;13(1):25.

Cheyne H, Abhyankar P, McCourt C. Empowering change: realist evaluation of a Scottish Government programme to support normal birth. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1110-1121.

Gardner KL, Dowden M, Togni S, Bailie R. Understanding uptake of continuous quality improvement in Indigenous primary health care: lessons from a multi-site case study of the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease project. Implementation science : IS. 2010;5:21.

Della Penna R, Martel H, Neuwirth EB, et al. Rapid spread of complex change: a case study in inpatient palliative care. BMC health services research. 2009;9:245.

Clarke CL, Keyes SE, Wilkinson H, et al. Organisational space for partnership and sustainability: lessons from the implementation of the National Dementia Strategy for England. Health & social care in the community. 2014;22(6):634-645.

Hung D, Gray C, Martinez M, et al. Acceptance of lean redesigns in primary care: A contextual analysis. Health care management review. 2017;42(3):203-212.

Marshall M, Mountford J, Gamet K, et al. Understanding quality improvement at scale in general practice: a qualitative evaluation of a COPD improvement programme. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(629):E745-E751.

McMullen H, Griffiths C, Leber W, Greenhalgh T. Explaining high and low performers in complex intervention trials: a new model based on diffusion of innovations theory. Trials. 2015;16:242.

Noyes J, Lewis M, Bennett V, et al. Realistic nurse-led policy implementation, optimization and evaluation: novel methodological exemplar. Journal of advanced nursing. 2014;70(1):220-237.

Rogers KM, Childers DJ, Messler J, et al. Glycemic control mentored implementation: creating a national network of shared information. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2014;40(3):111-118.

Parv L, Kruus P, Motte K, Ross P. An evaluation of e-prescribing at a national level. Informatics for health & social care. 2016;41(1):78-95.

Pearce C, Bartlett J, McLeod A, et al. Effectiveness of local support for the adoption of a national programme--a descriptive study. Informatics in primary care. 2014;21(4):171-178.

van Schendel RV, van El CG, Pajkrt E, et al. Implementing non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy in a national healthcare system: global challenges and national solutions. BMC health services research. 2017;17(1):670.

Azar J, Adams N, Boustani M. The Indiana University Center for Healthcare Innovation and Implementation Science: Bridging healthcare research and delivery to build a learning healthcare system. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2015;109(2):138-143.

Best A, Berland A, Herbert C, et al. Using systems thinking to support clinical system transformation. Journal of health organization and management. 2016;30(3):302-323.

Blue-Howells JH, Clark SC, van den Berk-Clark C, McGuire JF. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Justice programs and the sequential intercept model: case examples in national dissemination of intervention for justice-involved veterans. Psychological services. 2013;10(1):48-53.

Boustani MA, Frame A, Munger S, et al. Connecting research discovery with care delivery in dementia: the development of the Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia. Clinical interventions in aging. 2012;7:509-516.

Box TL, McDonell M, Helfrich CD, et al. Strategies from a nationwide health information technology implementation: the VA CART story. Journal of general internal medicine. 2010;25 Suppl 1:72-76.

Cyr J, Paige P, Paige P, Fisher D. Sustaining and spreading reduced door-to-balloon times for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2009;35(6):297-306.

Clark SR, Wilton L, Baune BT, et al. A state-wide quality improvement system utilising nurse-led clinics for clozapine management. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):254-259.

Duckers ML, Groenewegen PP, Wagner C. Quality improvement collaboratives and the wisdom of crowds: spread explained by perceived success at group level. Implementation science : IS. 2014;9:91.

Elson SL, Hiatt RA, Anton-Culver H, et al. The athena breast health network: Developing a rapid learning system in breast cancer prevention, screening, treatment, and care. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;140(2):417-425.

Goetz MB, Hoang T, Bowman C, et al. A System-wide Intervention to Improve HIV Testing in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(8):1200–1207.

Grayson ML, Russo PL, Cruickshank M, et al. Outcomes from the first 2 years of the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative. The Medical journal of Australia. 2011;195:615-619.

Harris JG, Bingham CA, Morgan EM. Improving care delivery and outcomes in pediatric rheumatic diseases. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2016;28(2):110-116.

Hendrich A, Tersigni AR, Jeffcoat S, et al. The Ascension Health journey to zero: lessons learned and leadership. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2007;33(12):739-749.

Johnson LC, Melmed GY, Nelson EC, et al. Fostering Collaboration Through Creation of an IBD Learning Health System. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017;112(3):406-408.

Kellogg KC, Gainer LA, Allen AS, et al. An intraorganizational model for developing and spreading quality improvement innovations. Health care management review. 2017;42(4):292-302.

Kwon S, Florence M, Grigas P, et al. Creating a learning healthcare system in surgery: Washington State's Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) at 5 years. Surgery. 2012;151(2):146-152.

Lannon CM, Peterson LE. Pediatric collaborative improvement networks: background and overview. Pediatrics. 2013;131 Suppl 4:S189-195.

Lennon MR, Bouamrane MM, Devlin AM, et al. Readiness for Delivering Digital Health at Scale: Lessons From a Longitudinal Qualitative Evaluation of a National Digital Health Innovation Program in the United Kingdom. Journal of medical Internet research. 2017;19(2):e42.

Mills PD, Weeks WB, Surott-Kimberly BC. A multihospital safety improvement effort and the dissemination of new knowledge. Joint Commission journal on quality and safety. 2003;29(3):124-133.

Ovseiko PV, O'Sullivan C, Powell SC, et al. Implementation of collaborative governance in cross-sector innovation and education networks: evidence from the National Health Service in England. BMC health services research. 2014;14:552.

Psek WA, Stametz RA, Bailey-Davis LD, et al. Operationalizing the learning health care system in an integrated delivery system. EGEMS (Washington, DC). 2015;3(1):1122.

Ramsey LB, Mizuno T, Vinks AA, Margolis PA. Learning Health Systems as Facilitators of Precision Medicine. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2017;101(3):359-367.

Resnick SG, Rosenheck R. Dissemination of supported employment in Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2007;44(6):867-877.

Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA. Scaling up the dissemination of evidence-based mental health practice to large systems and long-term time frames. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC). 2009;60(5):682-685.

Rocker GM, Amar C, Laframboise WL, et al. Spreading improvements for advanced COPD care through a Canadian Collaborative. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2017;12:2157-2164.

Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Families, systems & health : the journal of collaborative family healthcare. 2010;28(2):91-113.

Curran GM, Pyne J, Fortney JC, et al. Development and implementation of collaborative care for depression in HIV clinics. AIDS care. 2011;23(12):1626-1636.

Luck J, Hagigi F, Parker LE, et al. A social marketing approach to implementing evidence-based practice in VHA QUERI: the TIDES depression collaborative care model. Implementation science : IS. 2009;4:64.

Sherman SE, Fotiades J, Rubenstein LV, et al. Teaching systems-based practice to primary care physicians to foster routine implementation of evidence-based depression care. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2007;82(2):168-175.

Smith JL, Williams JW, Jr., Owen RR, et al. Developing a national dissemination plan for collaborative care for depression: QUERI Series. Implementation science : IS. 2008;3:59

Schmittdiel JA, Dlott R, Young JD, et al. The Delivery Science Rapid Analysis Program: A Research and Operational Partnership at Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Learning health systems. 2017;1(4).

Septimus E, Hickok J, Moody J, et al. Closing the Translation Gap: Toolkit-based Implementation of Universal Decolonization in Adult Intensive Care Units Reduces Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infections in 95 Community Hospitals. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016;63(2):172-177.

Yano EM. A Partnered Research Initiative to Accelerate Implementation of Comprehensive Care for Women Veterans The VA Women's Health CREATE. Medical Care. 2015;53(4):S10-S14.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following individuals: Shereef Elnahal, MD, VA Office of Organizational Excellence (10E); Ryan Vega, MD, Director, Diffusion of Excellence Initiative, VA Center for Innovation; Saurabha Bhatnagar, MD, Acting Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health, Office of Quality, Safety, and Value (10E2); Nick Bowersox, PhD, ABPP, Director, QUERI Center for Implementation and Evaluation Resources; Laura Damschroder, MS, MPH, Investigator, HSR&D Center for Clinical Management Research; Amy Kilbourne, PhD, MPH, Director, QUERI; George Jackson, PhD, MHA, Healthcare Epidemiologist, HSR&D Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care; Joe Francis, MD, MPH, Director, Clinical Analytics and Reporting, Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence; Peter Almenoff, MD, Senior Advisor, Office of the Secretary of the VA, Director, Organizational Excellence; David Ganz, MD, PhD, Corresponding PI, Care Coordination QUERI Program; Christian D. Helfrich, PhD, MPH, Research Investigator, Seattle-Denver Center of Innovation for Veteran-Centered and Value-Driven Care; and Roberta Shanman, RAND Corp.

Funding

This review is part of a larger review commissioned by the Department of Veterans Affairs, funded by the Veterans Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, including funds from the Evidence Synthesis Program (VA ESP Project #05-226) and additional support from the Care Coordination QUERI program project (QUE 15-276). The opinions expressed represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior presentations: “Scaling beyond early adopters: A systematic review and key informant perspectives”. Poster presentation at the 12th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation, Washington D.C. December 4, 2019.

“Scaling Beyond Early Adopters: Key Informant Perspectives.” Poster presentation at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, Washington D.C. June 3, 2019.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 27 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miake-Lye, I., Mak, S., Lam, C.A. et al. Scaling Beyond Early Adopters: a Content Analysis of Literature and Key Informant Perspectives. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 383–395 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06142-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06142-0