Abstract

Background

Effective hypertension self-management interventions are needed for socially disadvantaged African Americans, who have poorer blood pressure (BP) control compared to others.

Objective

We studied the incremental effectiveness of contextually adapted hypertension self-management interventions among socially disadvantaged African Americans.

Design

Randomized comparative effectiveness trial.

Participants

One hundred fifty-nine African Americans at an urban primary care clinic.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to receive (1) a community health worker (“CHW”) intervention, including the provision of a home BP monitor; (2) the CHW plus additional training in shared decision-making skills (“DoMyPART”); or (3) the CHW plus additional training in self-management problem-solving (“Problem Solving”).

Main Measures

We assessed group differences in BP control (systolic BP (SBP) < 140 mm Hg and diastolic BP (DBP) < 90 mmHg), over 12 months using generalized linear mixed models. We also assessed changes in SBP and DBP and participants’ BP self-monitoring frequency, clinic visit patient-centeredness (i.e., extent of patient-physician discussions focused on patient emotional and psychosocial concerns), hypertension self-management behaviors, and self-efficacy.

Key Results

BP control improved in all groups from baseline (36%) to 12 months (52%) with significant declines in SBP (estimated mean [95% CI] − 9.1 [− 15.1, − 3.1], − 7.4 [− 13.4, − 1.4], and − 11.3 [− 17.2, − 5.3] mmHg) and DBP (− 4.8 [− 8.3, − 1.3], − 4.0 [− 7.5, − 0.5], and − 5.4 [− 8.8, − 1.9] mmHg) for CHW, DoMyPART, and Problem Solving, respectively). There were no group differences in BP outcomes, BP self-monitor use, or clinic visit patient-centeredness. The Problem Solving group had higher odds of high hypertension self-care behaviors (OR [95% CI] 18.7 [4.0, 87.3]) and self-efficacy scores (OR [95% CI] 4.7 [1.5, 14.9]) at 12 months compared to baseline, while other groups did not. Compared to DoMyPART, the Problem Solving group had higher odds of high hypertension self-care behaviors (OR [95% CI] 5.7 [1.3, 25.5]) at 12 months.

Conclusion

A context-adapted CHW intervention was correlated with improvements in BP control among socially disadvantaged African Americans. However, it is not clear whether improvements were the result of this intervention. Neither the addition of shared decision-making nor problem-solving self-management training to the CHW intervention further improved BP control.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01902719

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

African Americans have poorer blood pressure (BP) control compared to other racial groups.1 Interventions tailored to support patients’ BP self-management by addressing individuals’ social and cultural barriers to care have been widely advocated as a potential mechanism to address disparities in BP control.2

Socially disadvantaged African Americans often face several barriers to achieving hypertension control which could require tailored interventions. These barriers include suboptimal self-management skills or support, cultural beliefs about treatment, or logistical barriers to care.3,4,5,6 Previous studies have suggested beneficial effects of community health workers, BP self-monitoring, decision-support, and self-management training on BP control.5, 7,8,9,10,11 However, it is unclear whether these interventions, when tailored to their social contexts and combined, could help socially disadvantaged African Americans address these barriers and better engage in their hypertension self-management and clinical care.

Urban primary care clinics with limited resources often deliver hypertension care to socially disadvantaged African Americans with substantial comorbid illness.12, 13 Studies comparing the effectiveness of tailored interventions to improve hypertension self-management in urban primary care settings could provide evidence needed to support interventions’ judicious deployment. We conducted a randomized comparative effectiveness trial to study the effectiveness of three BP self-management interventions tailored to address material, social, and self-management skills needs of socially disadvantaged African Americans receiving hypertension care in an urban primary care clinic.

METHODS

The Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) study was a 12-month pragmatic, randomized comparative effectiveness clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT01902719]). The Johns Hopkins and Duke Medicine Institutional Review Boards approved all protocols, consent, and data analysis procedures. Study enrollment occurred between September 2013 and June 2014.

Study Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited from an academically affiliated community-based primary care clinic in East Baltimore, Maryland. We identified potentially eligible patients by screening clinic electronic health records. Eligible patients were English-speaking adults aged 18 or greater who received care in the clinic, self-identified themselves as African American, and had uncontrolled hypertension (at least two measures of systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg obtained at the clinic within the 6 months prior to screening and recruitment). We excluded patients from participating if they were pregnant for ethical, safety, and compliance reasons. Study participants’ physicians provided consent to have clinic visit conversations audio-recorded.

Study Interventions

We developed ACT study interventions to address social contexts of residents of East Baltimore with input from community and clinic stakeholders.14,15,16,17,18 Stakeholders wanted all study participants to interact with CHWs and receive self-BP monitors.14 One group (“CHW”) received no additional intervention. A second group (“DoMyPART”) received the CHW intervention plus training in how to engage in shared health decision-making about hypertension self-care. A third group (“Problem Solving”) received the CHW intervention plus 9 weeks of Problem Solving behavioral self-management training in the clinic.

A complete description of ACT Study protocols is published elsewhere.14, 19 Two CHWs from the Baltimore community trained in community health education20 visited participants in their homes and provided them with a home BP monitor (Omron 10 Series BP791IT or Life Source). During the home visit, CHWs trained participants to use monitors and counseled them about hypertension self-management behaviors. CHWs visited participants in a scheduled and ad hoc manner throughout the study through in-person and telephone contacts. Each participant saw the same CHW throughout the study. CHWs helped participants check their BP monitors to verify BP control and linked participants to clinic nurses if their home BP was not under control. CHWs reinforced self-management behaviors and helped participants address barriers to hypertension care, including clinic appointment adherence, managing acute care transitions, and contextual barriers (e.g., financial or transportation) to care.

In addition to the CHW interaction, “DoMyPART” participants received a one-time training just prior to a routinely scheduled clinic visit with their primary care provider to encourage shared decision-making with their physicians by following four key “PART” steps (“P”repare for their visits; “A”ct during their visits; “R”eview key recommendations; and “T”ake recommendations home). The interventionist helped participants practice skills and provided participants with a workbook and a reminder card reviewing the PART steps.

In addition to the CHW interaction, “Problem Solving” participants were invited to attend nine weekly structured group sessions held in the clinic and led by a trained interventionist where they received hypertension self-management education and problem-solving skills training to overcome barriers to self-management.

Participant Enrollment and Randomization

Study staff contacted potentially eligible patients via telephone. Interested patients provided verbal consent and completed a telephone questionnaire to preliminarily ascertain their eligibility. Within 21 days of the telephone questionnaire, participants attended a clinic enrollment visit to confirm eligibility. At this time, participants provided written consent for enrollment procedures, study interventions, and follow-up assessments. Participants were subsequently visited at home by a CHW and research staff member. During this visit, they were randomly assigned to intervention groups in a 1:1:1 ratio, using a computer validated algorithm generated by a study statistician who was not involved in participant group assignment or outcomes assessments. Participants could not be blinded to their treatment groups. Data collectors, who were blinded to participants’ intervention assignment and not involved in analyzing data, assessed behavioral and BP outcomes using objective measures 4 and 12 months after randomization. Participants were reimbursed for their time completing study questionnaires ($50-$75 per questionnaire), attending study examination visits ($20 per visit), and for attending DoMyPART training ($25 for the one time training) and Problem Solving classes ($25 for each of the 9 classes).

Study Measures

At baseline, we assessed participants’ sociodemographic characteristics via telephone. We measured health literacy during the enrollment visit using the validated 6-item Newest Vital Sign measure.21 Study data were collected by trained interviewers and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Johns Hopkins University.22

BP for all study assessments was measured by trained and certified study staff using an automatic oscillometric monitor (Omron HEM-907XL) programmed with a 5-min delay followed by three measurements separated by 30 s. The staff recorded all three measures and the average at each visit. At the enrollment home visit, CHWs recorded participants’ medications. During study examinations performed in the clinic, trained research assistants measured participants’ BP, height, and weight, and obtained serum and urine laboratory assessments later processed in a standard laboratory. At baseline, we assessed participants’ diabetes status as the presence of any of the following characteristics, including a diabetes diagnosis in the electronic health record (ICD-9-CM codes 250.0-250.9), a hemoglobin A1c > 6.5 mg/dl, a fasting serum glucose of > 126 mg/dl, or participants’ prescribed medications for diabetes. We assessed CKD as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or albumin-to-creatinine ratio > 30 mg/g as having CKD.23 We also assessed participants’ self-reported comorbid conditions, as well as their use of alcohol or illicit drugs, physical activity, and antihypertensive medication use.24,25,26

When patients attended routinely scheduled clinic visits, study staff downloaded data from participants’ home BP monitors to ascertain the times and dates of each measure. Study staff also audio-recorded discussions between study participants and their consenting physicians during participants’ first routine clinic visit post-study enrollment.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was BP control defined by the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-7) guidelines (SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg).27 We also assessed BP control according to JNC-8 which emerged during the study (SBP < 150 and DBP < 90 for participants age 60 years or older; SBP < 140 and DBP < 90 for participants younger than 60 years).28 We also assessed participants’ change in SBP and DBP.

We captured intermediary outcomes reflecting proximal effects of each intervention. For CHW and monitoring, we assessed the number of participant-CHW interactions and participants’ average number of home BP cuff measures (number of days per month each participant’s BP monitor indicated a BP had been taken, divided by the total number of days in each month). CHWs also recorded the reason for each CHW visit using structured case report forms. For DoMyPART, we assessed the patient-centeredness of patient-physician interactions by coding audio recordings of participants’ first routinely scheduled clinic visit after enrollment using the validated Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS). Patient-centeredness was computed as a ratio reflecting emotional and psychosocial exchange in the numerator relative to a denominator that is characterized by medical condition, treatment, and procedural exchange (lower ratios indicating less patient-centered encounters).18, 29,30,31,32,33 For Problem Solving, we used three subscales (score range for each 0–80) of the validated Hypertension Self-care Profile to measure participants’ self-reported self-management knowledge, behaviors, and self-efficacy.34 We considered participants’ self-reported self-management behaviors and self-efficacy to be “high” if sub-scale scores were > 60.34 We also assessed medication adherence using the validated Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.35 We measured participants’ self-management problem-solving skills using the validated Health Problem-Solving Scale (score range 0–200; greater scores indicating better skills).36, 37

Statistical Analysis

We described participants’ baseline characteristics. We quantified differences in the probability of BP control at follow-up between groups using JNC-7 and JNC-8 criteria and assessed differences in changes in SBP and DBP using generalized linear mixed models and incorporated random intercepts for participants’ physician at baseline, the CHW assigned at baseline, and to account for repeated measurements on participants over time. In sensitivity analyses, we performed multiple imputation for all primary models to account for missing data. We also fit constrained mixed models assuming a common baseline BP across groups.38, 39

Additive interventions were designed to increase participants’ capacities to engage with their health care providers on decisions around hypertension care (DoMyPART) and to enhance their hypertension self-management skills (Problem Solving). We therefore hypothesized a priori that the DoMyPART and Problem Solving groups would each achieve incremental improvements in BP control compared to the CHW group. We estimated the CHW intervention would result in 50% BP control9 and calculated that a sample size of 336 participants would achieve 98% power to detect 75% and 80% BP control in DoMyPART and Problem Solving arms, respectively.14

Despite their uncontrolled clinic BPs at screening, some participants had controlled BP measured by study staff at enrollment. We therefore conducted a subgroup analysis among those with uncontrolled BP at the baseline study visit. We also assessed subgroup effects among participants with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and/or diabetes (i.e., CKD only, diabetes only, both CKD and diabetes, or neither condition) by incorporating interaction terms into primary mixed models.

We compared groups’ home BP monitor use using a Kruskal-Wallis test. We compared groups’ patient-centeredness ratios using a linear mixed model adjusted for clustering of patients among clinic providers and CHW. We used generalized mixed models described above to compare groups’ self-management, medication adherence, and problem-solving. In post hoc analyses, we described characteristics of participants’ who adhered (versus not) to the DoMyPART and Problem Solving interventions. We performed analyses using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.3.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). All hypothesis tests were two-sided using a 0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

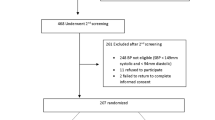

Participant Eligibility, Enrollment, and Retention

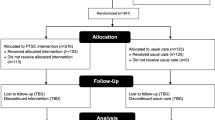

Of 402 clinic patients assessed for eligibility, 159 persons were enrolled and randomly assigned to intervention groups. Recruitment fell short of our projected estimate due to prolonged stakeholder engagement and time limitations.19 Thus, we only enrolled 159 participants, yielding 80% power to detect a statistically significant difference across study arms if participants achieved BP control rates 60%, 89%, and 94% in their respective study arms at follow-up. Overall, 77%, 67%, and 61% of participants in CHW, DoMyPART, and Problem Solving, respectively, completed their 12 months visits (Fig. 1).

Participant Sociodemographic, Behavioral, and Clinical Characteristics

Participants had a mean (SD) age of 57 (10.8) years and were predominantly (73.6%) female, and nearly half (39.0%) had less than high school education. Over half (53.5%) met the US Census Bureau poverty threshold standards.40 Nearly half (48.4%) had inadequate health literacy (score less than 2 on Newest Vital Sign measure)21. Few (11.9%) participants reported high self-management behaviors at baseline, while over half (58.5%) reported high self-efficacy with hypertension self-management. Few (20.1%) scored high on Morisky self-reported medication adherence. Despite a recent history of uncontrolled BP in the clinic, more than one third (35.8%) had BP under control when measured by study staff at enrollment. Participants’ median [IQR] SBP and DBP were 137 (125–152) and 80 (72–89) mmHg, respectively. Nearly half (47.8%) had diabetes and more than one third (37.7) had CKD. Most (91.8%) participants were taking anti-hypertension medications at the time of enrollment. Several (28.3%) participants were also taking medications to treat diabetes. These characteristics were similar across study groups (Table 1). Additional potential correlates of blood pressure control including participants’ self-reported histories of cardiovascular disease and other comorbidities, alcohol use, illicit drug use, exercise, body mass index (BMI), and hypertension medications prescribed were also similar across study groups (Supplemental Table 1).

Participant Receipt of Interventions

Participants had a median [IQR] 10 [8–14] CHW interactions, with no group differences. Most interactions focused on self-care behaviors, clinic appointment adherence, acute care episodes, and contextual barriers to care (Table 2). Most (85%) participants assigned to DoMyPART attended the skills training. Most (85%) participants assigned to Problem Solving attended at least 1 of 9 group sessions; 64% attended at least 5 of 9 sessions; and 23% attended all 9 sessions. Study staff who were not CHWs delivered the DoMyPART and Problem Solving interventions. Participants assigned to either the DoMyPART or Problem Solving interventions did not inadvertently receive other interventions besides the CHW intervention (i.e., there was no “crossover”). Demographic characteristics of participants who completed the DoMyPART or Problem Solving interventions were similar. (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Primary Outcome: BP Control

Among all participants at baseline, 4 months and 12 months, BP control was achieved among 36%, 51%, and 52% (JNC-7 criteria) and 50%, 65%, and 69% (JNC-8 criteria), respectively. Cross-sectional assessment of the percent participants achieving BP control at 12 months was not statistically significantly different among the three groups according to JNC-7 or JNC-8 criteria (Table 3).

Within each group, there were greater odds of BP control at 12 months compared to baseline, using JNC-7 criteria. This finding was statistically significant for the DoMyPART and Problem Solving groups, but it was not statistically significant for the CHW group. There were no between-group differences in the odds of achieving BP control over 12 months. Findings were similar when defining BP control according to JNC-8 criteria (Fig. 2 and Table 4). There were no statistically significant interactions in the effect of the interventions by participants’ diagnosis of CKD or diabetes.

Secondary Outcome: BP Change

Participants’ mean (SD) SBP and DBP declined 9.7 (21.4) mmHg and 4.6 (12.6) mmHg, respectively, during follow-up, but declines did not statistically significantly differ across study groups. In linear mixed models, predicted mean SBP and DBP declines were similar for CHW, DoMyPART, and Problem Solving groups. Participants with uncontrolled BP at enrollment experienced greater SBP declines, but there were no differences between groups. Inferences for primary and secondary BP outcomes were similar in multiple imputation and constrained analyses (Table 4).

Intermediary Outcomes

Most participants (87%, 74%, and 74% in CHW, DoMyPART, and Problem Solving, respectively) used their home BP monitors. Participants measured their BP a median [IQR] 6 (3–9) days per month, with no statistically significant differences among groups. Patient-centeredness scores from participants’ first routine clinic visit after enrollment (and after DoMyPART training) reflected that patient-physician discussions focused less on patients’ emotional or psychosocial concerns and more on their biomedical concerns overall (median ratio of emotional/psychosocial to biomedical talk [IQR] 0.7 [0.5–0.9] for all participants, with no difference among groups). Problem Solving participants had statistically significantly greater odds of high self-reported hypertension self-care behaviors (OR [95% CI] 18.7 [4.0, 87.3]) and self-efficacy (OR [95% CI] 4.7 [1.5, 14.9]) scores at 12 months compared to baseline, while participants in CHW and DoMyPART did not. Problem Solving participants had higher odds than DoMyPART participants of achieving high self-reported hypertension self-care behaviors at 12 months (OR [95% CI] 5.7 [1.3, 25.5]) but there were no other between-group differences (Table 5). There were no statistically significant differences in knowledge or medication adherence among groups. Participants’ overall mean (SD) problem-solving scores were 19.1 (3.4), 20.3 (3.1), and 20.5 (2.9) at baseline, 4 months, and 12 months, respectively. Problem-solving scores increased similarly for all three groups over 12 months (average point increase [95% CI] 1.3 [0.4, 2.1], 1.1 [0.2, 1.9], and 1.5 [0.7, 2.3] in CHW, DoMyPART, and Problem Solving, respectively; p = 0.57).

Discussion

While all ACT study groups experienced improvements in BP control over 12 months, neither DoMyPART (designed to enhance patient engagement with their physicians on decisions around hypertension care) nor Problem Solving training (designed to enhance patients’ self-management skills) groups experienced any added blood pressure improvements beyond those experienced by the CHW group .

The ACT CHW self-monitoring intervention was designed to have a potent effect through its pairing of CHW support with BP self-monitoring to address participants’ contextual barriers to hypertension self-care. Both CHWs and BP self-monitoring have been previously shown to be effective adjuvants in hypertension care.7, 8, 41 ACT study findings extend existing evidence on these interventions by suggesting their effectiveness among socially disadvantaged African Americans in primary care, although it is important to note that since there was no control group that did not receive the CHW intervention, it is not clear that the CHW intervention itself led to improved BP control.

The ACT study was not designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the CHW intervention itself. However, frequent contact between trained and supervised CHWs and patients and the provision of BP monitors may have helped overcome important social support, and logistical and material resource barriers for socially disadvantaged individuals. BP improvements were substantial overall, particularly among those with uncontrolled BP at baseline, suggesting the CHW self-monitoring intervention may have been an important adjuvant to routine care. In the context of a low-resource urban primary care setting, cost of implementing the CHW self-monitoring intervention may warrant consideration. The CHW self-monitoring intervention required substantial staff time and financial resources to purchase BP self-monitors. Despite this, a recent cost-effectiveness analysis suggested that the financial costs of interventions resulting in similar BP improvement could be offset by cost savings gained through improvements in health.42

While the DoMyPART and Problem Solving interventions did not appear to substantially improve BP control above and beyond CHW self-monitoring, they may still have benefits for socially disadvantaged populations by supporting patients’ capacities to engage meaningfully in hypertension care. Consistent with prior studies, participants receiving the Problem Solving training experienced significant improvements in self-management behavior and self-efficacy, suggesting this intervention may add value to hypertension care.43,44,45

The ACT was conducted in a relatively small population of African Americans in a single urban primary care practice, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings. Further, recruitment did not achieve planned goals, and we may have not achieved adequate statistical power. Also, despite screening potential participants via their electronic health records, nearly one third to one half had controlled BP at the time of study enrollment, highlighting the potential pitfalls of this screening approach. Nonetheless, the percentage of persons with controlled BP at baseline was similar among all groups, and our subgroup analyses among those with uncontrolled BP at baseline were consistent with main findings. Additionally, only 85% and 64% of participants attended the DoMyPART and Problem Solving sessions, despite study staff encouragement. This suboptimal completion may provide important insights regarding adherence to similar interventions in other primary care clinics. Finally, since the ACT study did not include a study group receiving only usual primary care, it is possible that observed BP improvements were the result of secular trends or regression to the mean, rather than the CHW intervention.

In summary, socially disadvantaged African Americans receiving CHW and self-monitoring interventions experienced significant improvements in BP. While problem-solving self-management training may have improved patients’ self-management skills and self-efficacy, neither shared decision-making nor problem-solving self-management training incrementally improved BP. Studies exploring how BP improvements can be sustained in this population are needed.

References

Redmond, N.; Baer, H.J.; Hicks, L.S. Health behaviors and racial disparity in blood pressure control in the national health and nutrition examination survey. Hypertension. 2011 Mar;57(3):383-389.

Scisney-Matlock, M.; Bosworth, H.B.; Giger, J.N., et al. Strategies for implementing and sustaining therapeutic lifestyle changes as part of hypertension management in African Americans. Postgrad Med. 2009 May;121(3):147-159.

Flynn, S.J.; Ameling, J.M.; Hill-Briggs, F., et al. Facilitators and barriers to hypertension self-management in urban African Americans: perspectives of patients and family members. Patient preference and adherence. 2013;7:741-749.

Greer, D.B.; Ostwald, S.K. Improving adherence in African American women with uncontrolled hypertension. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015 Jul-Aug;30(4):311-318.

Johnson, H.M.; Warner, R.C.; LaMantia, J.N.; Bowers, B.J. “I have to live like I’m old.” Young adults’ perspectives on managing hypertension: a multi-center qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016 Mar 11;17:31.

Rimando, M. Perceived Barriers to and Facilitators of Hypertension Management among Underserved African American Older Adults. Ethn Dis. 2015 Aug 7;25(3):329-336.

Allen, C.G.; Brownstein, J.N.; Satsangi, A.; Escoffery, C. Community Health Workers as Allies in Hypertension Self-Management and Medication Adherence in the United States, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016 Dec 29;13:E179.

Brownstein, J.N.; Chowdhury, F.M.; Norris, S.L., et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007 May;32(5):435-447.

Cooper, L.A.; Roter, D.L.; Carson, K.A., et al. A randomized trial to improve patient-centered care and hypertension control in underserved primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Nov;26(11):1297-1304.

Fletcher, B.R.; Hinton, L.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Roberts, N.W.; Bobrovitz, N.; McManus, R.J. Self-monitoring blood pressure in hypertension, patient and provider perspectives: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 Feb;99(2):210-219.

Hill-Briggs, F.; Lazo, M.; Peyrot, M., et al. Effect of problem-solving-based diabetes self-management training on diabetes control in a low income patient sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Sep;26(9):972-978.

Fryer, A.K.; Doty, M.M.; Audet, A.M. Sharing resources: opportunities for smaller primary care practices to increase their capacity for patient care. Findings from the 2009 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians. Issue brief (Commonwealth Fund). 2011 Mar;4:1-15.

Harvey, J.; Dopson, S.; McManus, R.J.; Powell, J. Factors influencing the adoption of self-management solutions: an interpretive synthesis of the literature on stakeholder experiences. Implementation science : IS. 2015 Nov 13;10:159.

Ameling, J.M.; Ephraim, P.L.; Bone, L.R., et al. Adapting hypertension self-management interventions to enhance their sustained effectiveness among urban African Americans. Fam Community Health. 2014 Apr-Jun;37(2):119-133.

Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. xiii, 617-xiii, 617 p.

D’Zurilla, T.J.; Goldfried, M.R. Problem solving and behavior modification. J Abnorm Psychol. 1971;78(1):107-126.

Gielen, A.C.; McDonald, E.M. In: Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Lewis, F.M., editors. Vol. 3, Using the Precede-Proceed Planning Model to Apply Helath Behavior Theories. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 409-436.

Roter, D.; Larson, S. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002 Apr;46(4):243-251.

Ephraim, P.L.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Roter, D.L., et al. Improving urban African Americans’ blood pressure control through multi-level interventions in the Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) study: a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014 Jul;38(2):370-382.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Materials for African American Audiences [July 10, 2019]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/healthdisp/aa.htm

Weiss, B.D.; Mays, M.Z.; Martz, W., et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005 Nov-Dec;3(6):514-522.

Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009 Apr;42(2):377-381.

Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H., et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009 May 5;150(9):604-612.

Ainsworth, B.E.; Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Strath, S.J., et al. Comparison of three methods for measuring the time spent in physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000 Sep;32(9 Suppl):S457-464.

Ewing, J.A. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984 Oct 12;252(14):1905-1907.

Smith, P.C.; Schmidt, S.M.; Allensworth-Davies, D.; Saitz, R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Jul 12;170(13):1155-1160.

Chobanian, A.V.; Bakris, G.L.; Black, H.R.; et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The jnc 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2571.

James, P.A.; Oparil, S.; Carter, B.L., et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014 Feb 5;311(5):507-520.

Bertakis, K.D.; Roter, D.; Putnam, S.M. The relationship of physician medical interview style to patient satisfaction. J Fam Pract. 1991 Feb;32(2):175-181.

Levinson, W.; Roter, D.L.; Mullooly, J.P.; Dull, V.T.; Frankel, R.M. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997 Feb 19;277(7):553-559.

Roter, D.L. Patient participation in the patient-provider interaction: the effects of patient question asking on the quality of interaction, satisfaction and compliance. Health Educ Monogr. 1977 Winter;5(4):281-315.

Roter, D.L.; Hall, J.A.; Katz, N.R. Relations between physicians’ behaviors and analogue patients’ satisfaction, recall, and impressions. Med Care. 1987 May;25(5):437-451.

Wissow, L.S.; Roter, D.; Bauman, L.J., et al. Patient-provider communication during the emergency department care of children with asthma. The National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD. Med Care. 1998 Oct;36(10):1439-1450.

Han, H.R.; Lee, H.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Kim, M. Development and validation of the Hypertension Self-care Profile: a practical tool to measure hypertension self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014 May-Jun;29(3):E11-20.

Moon, S.J.; Lee, W.Y.; Hwang, J.S.; Hong, Y.P.; Morisky, D.E. Accuracy of a screening tool for medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8. PLoS One 2017;12(11):e0187139.

Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Hill-Briggs, F. Measuring health-related problem solving among African Americans with multiple chronic conditions: application of Rasch analysis. J Behav Med. 2015 Oct;38(5):787-797.

Hill-Briggs, F.; Gemmell, L.; Kulkarni, B.; Klick, B.; Brancati, F.L. Associations of patient health-related problem solving with disease control, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations in HIV and diabetes clinic samples. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 May;22(5):649-654.

Liu, G.F.; Lu, K.; Mogg, R.; Mallick, M.; Mehrotra, D.V. Should baseline be a covariate or dependent variable in analyses of change from baseline in clinical trials? Stat Med. 2009 Sep 10;28(20):2509-2530.

Fitzmaurice GM; Laird NM; Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Willey 2011.

U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty Thresholds; []. Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html

Cappuccio, F.P.; Kerry, S.M.; Forbes, L.; Donald, A. Blood pressure control by home monitoring: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2004 Jul 17;329(7458):145.

Moran, A.E.; Odden, M.C.; Thanataveerat, A., et al. Cost-effectiveness of hypertension therapy according to 2014 guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jan 29;372(5):447-455.

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122-147.

Bosworth, H.B.; Olsen, M.K.; Grubber, J.M., et al. Two self-management interventions to improve hypertension control: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Nov 17;151(10):687-695.

O’Leary, A. Self-efficacy and health. Behav Res Ther. 1985 1985/01/01/;23(4):437-451.

Funding

Drs. Boulware, Cooper, Hill-Briggs, Levine, Roter, and Ms. Ephraim were supported with the grant P50 HL105187; Dr. Wolff was supported with the grant K01MH082885; Dr. Greer was supported with the grant K23DK094975; Dr. Crews was supported with the grant K23DK097184; Dr. Gudzune was supported with the grant K23HL116601; Dr. Davenport was supported with the grant UL1TR002553.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and attest to the accuracy and integrity of the work. All authors have given final approval for the work to be published. The contributions of each author are as follows: LEB—study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; PLE—study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; FH-B—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; DLR—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; LRB—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; JLW—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; LL-B—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; DML—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; HCR—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; JMA—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; CAD—data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; H-JL—data analysis, data interpretation; JFP—data analysis, data interpretation; N-YW—study design, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; KAC—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; VS—data collection, drafting manuscript; DJG—data collection, drafting manuscript; SJF—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; DM—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; DH—study design, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; LP—study design, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; MS—study design, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; AF—study design, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; ND—data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; JC—study design; HJA—study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript; ANC—drafting manuscript; LAC—study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The Johns Hopkins and Duke Medicine Institutional Review Boards approved all protocols, consent, and data analysis procedures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 39 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boulware, L.E., Ephraim, P.L., Hill-Briggs, F. et al. Hypertension Self-management in Socially Disadvantaged African Americans: the Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 142–152 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05396-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05396-7