Abstract

Background

Few programs train residents in recognizing and responding to distressed colleagues at risk for suicide.

Aim

To assess interns’ ability to identify a struggling colleague, describe resources, and recognize that physicians can and should help colleagues in trouble.

Setting

Residency programs at an academic medical center.

Participants

One hundred forty-five interns.

Program Design

An OSCE case was designed to give interns practice and feedback on their skills in recognizing a colleague in distress and recommending the appropriate course of action. Embedded in a patient “sign-out” case, standardized health professionals (SHP) portrayed a resident with depressed mood and an underlying drinking problem. The SHP assessed intern skills in assessing symptoms and directing the resident to seek help.

Program Evaluation

Interns appreciated the opportunity to practice addressing this situation. Debriefing the case led to productive conversations between faculty and residents on available resources. Interns’ skills require further development: while 60% of interns asked about their colleague’s emotional state, only one-third screened for depression and just under half explored suicidal ideation. Only 32% directed the colleague to specific resources for his depression (higher among those that checked his emotional state, 54%, or screened for depression, 80%).

Discussion

This OSCE case identified varying intern skill levels for identifying and assessing a struggling colleague while also providing experiential learning and supporting a culture of addressing peer wellness.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Residency training is demanding. Young professionals must regularly assimilate new cultural norms as they rotate from one clinical service to another, all while under pressure to learn and perform the responsibilities of being a physician. Even with limits on work hours and efforts to implement resident wellness programs,1,2 many trainees will struggle with mental health issues, which are common among practicing physicians as in the general public.3,4 One prospective study of 740 interns across 13 hospitals found that the incidence of depression increased from 4 to 27% and thoughts of death increased by 370% in the first 3 months of internship.5 In addition, symptoms may go unrecognized. A sample of program directors estimated the prevalence of alcoholism risk to be 1% in their trainees when 13% of their residents’ CAGE scores indicated risk for alcoholism.6 Recent media coverage highlights growing concerns: intern suicides are highly covered news events, and opinion pieces written by interns have shed light on feelings of isolation in residency.7,8

Although residencies have implemented wellness curricula,9,10,11,12 house staff generally receive little training in recognizing a colleague at risk. Even if they are aware that a colleague needs help, stigma deters individuals from revealing emotional distress or seeking help for mental illness, and residents may be reluctant to recommend that peers get care.13 Yet residents spend a significant amount of time together sharing intense experiences and are therefore well positioned to identify and intervene with struggling colleagues. We wanted to address this issue in a way that would increase its visibility to faculty and house staff, make resources transparent, and equip our learners with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to assist struggling colleagues throughout their professional careers. In this paper, we describe how an objective structured clinical exam (OSCE) scenario that challenged interns to recognize and respond to a colleague’s problem behaviors and underlying mental health issues enabled us to assess their ability to identify a struggling colleague, describe available resources, and recognize that physicians can and should help colleagues in trouble.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

One hundred forty-five resident interns participated in the OSCE case between 2013 and 2017 in three residency programs in an academic medical center: medicine (N = 114), orthopedics (N = 9), and surgery (N = 22).

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

We designed a 10-min OSCE scenario as part of the annual multi-station OSCE in these three residency programs. In the scenario, the standardized health professional (SHP) presented as a fellow intern who was assigned to night coverage. The door instruction sheet tasked the participating interns to give a sign-out to the SHP who was late for his shift and had a reputation for being disorganized and a loner. If effectively engaged, the SHP reported distress, isolation, problem drinking, and if screened, symptoms of depression (see Table 1 for details). Objectives for the interns were to (1) elicit and recognize problem behaviors, (2) discuss their concerns with the colleague, (3) identify and recommend available resources, and (4) develop a strategy for a “warm hand off” to leadership/support services if appropriate. Residents participated in 5–10-min post-OSCE feedback/debriefing sessions with faculty who were trained to ask residents to assess their own performance, check in to see if they thought this was their role, and share relevant institutional policies/resources as appropriate to the encounter they just watched. Faculty were updated on the current resources and expectations at NYU SOM including access to GME psychiatrist free of charge, policy on time off for wellness, and how to escalate and perform a warm hand off to program leadership.

The SHP completed a checklist that assessed case-specific skills including depression, substance use screening, current life situation assessment, and follow-up plan. Each item was assessed using a not done, partly done, and well done scale with behavioral anchors for each option. Scores for two domains essential to this case, depression and life situation assessment, were calculated as % of items rated “well done.” Internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha for each domain was greater than or equal to 0.63. SHPs also provided comments about the intern’s overall performance.

After the OSCE, residents participated in a debriefing and feedback session of all cases and completed a survey where they reflected on the challenges of each case. We also met with faculty who conducted the feedback/debriefing to elicit their impressions of the case and its impact. The OSCE was held within the first half of the internship year as the schedule of the particular residency allowed.

Data are reported in this study only for those interns who provided consent for their routinely collected education data to be used for research as part of an IRB-approved Resident Medical Education Research Registry (78%, 145/187 consented). The consenting and non-consenting intern groups did not differ in gender (consenting, 28% female; non-consenting, 24% female; chi-square = .23, p = .63), age (consenting mean age, 26.1; non-consenting mean age, 25.8; t test = .21, p = .83), nor did the rate of consenting differ by program (orthopedics, 89% consent rate; surgery, 68% consent rate; medicine, 79% consent rate; chi-square = 1.91, p = .38) or by cohort year within program (start year 2012 consent rate, 89%; start year 2013 consent rate, 68%; start year 2014 consent rate, 80%; start year 2015 consent rate, 75%; chi-square = 2.04; p = .56).

PROGRAM EVALUATION

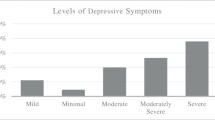

Table 2 summarizes interns’ performance (N = 145). While 60% of interns checked in on their colleague’s emotional state (e.g., “Do I need to worry about you?”), far fewer interns fully investigated their colleagues’ distress: only 33% of interns screened for depression using a two-question screen (depressed mood and anhedonia), and just 3% asked about additional symptoms such as loss of energy or appetite change. Regarding suicidal ideation, 30% of interns asked generally if the colleague thought about hurting himself, but only 16% fully assessed intent (passive vs. active).

Approximately 30% of interns explored the colleague’s support system, and only 14% assessed recent life stressors and changes. Few assessed alcohol use (19%).

A third of the interns directed their colleague to seek help. However, interns who screened for depression were close to two times more likely to direct their colleague to seek help (54% vs 32%) and nearly three times more likely to direct their colleague to seek help if they screened for suicidal ideation (80% vs 32%).

The SHP and faculty comments on intern performance echoed the checklist results in that both reported that while the vast majority of residents appeared to be sensitive to the interns’ distress and compassionate in their responses, far fewer were able to directly address the seriousness of his symptoms and the need for intervention [SHP comments: “you were very open and very good at listening to me. Which was great. The thing I would add though is that this guy is actually going through something that is pretty serious. This is something he really needs help for.” “Excellent identifying the problem as well as pushing me to do something about it. Not many people do that and I really want to stress how amazing that was.”] Faculty reported that virtually all of the interns were empathic about how hard internship was and many suggested a variety of supportive activities (dinner, weekend activity) even though they did not delve into the issues of drinking and depression. The SHPs also provided feedback to the handful of interns who focused on the sign-out task and largely ignored the resident’s distress: “I think perhaps you felt that you needed to get to sign-out, which understandably is a very big concern, but I also think you need to take the time to really see if you can help the person in front of you”. Faculty noted, with some surprise, the same observation that a few interns focused solely on the sign-out.

Overall performance (as assessed by depression and current life assessment scores) did not differ over time (2013–2017), ranging from 21 to 34% well done for depression assessment (ANOVA F = 1.21, p = .31) and from 11 to 26% well done for current life situation assessment (ANOVA F = .97, p = .44), or by residency program (depression assessment, 23% to 31% well done, ANOVA F = .85, p = .43; current life situation assessment, 11% to 26%, ANOVA F = .95, p = .37).

In the survey eliciting interns’ perceptions of what was challenging about this case, their comments fell into two main categories: (1) balancing the task of completing the “sign-out” with the unexpected complication of exploring and responding to the resident’s distress and (2) their discomfort with directly assessing a colleague’s impairment. Examples of interns’ comments reflecting the first category include “difficult to run through sign-out with his depression”, “trying to balance empathy with efficiency”, and “I wasn’t sure how much time to leave for the sign-out. I felt like the resident’s issues were more important to address, but I worry that I rushed through them to accomplish all my tasks”. The second category mainly involved interns’ discomfort probing their peer about his life circumstances and reported difficulty deciding where the boundaries lay between colleague, friend, and physician (examples of interns’ comments about what made this case challenging: “feeling comfortable enough to ask the resident personal questions”, “really hard to decide how far to probe a peer”). Some interns reported what was most challenging was their frustration in not knowing how to help and their concern about the seriousness of the situation: “I didn’t really know the resource information to pass along” “I failed to ask about suicidal intent”, “trying to deal with the safety of leaving the resident alone”. Overall, interns stated their appreciation for the case, noting that it allowed an opportunity to discuss the struggles interns face and find out how to access available resources. Many interns also commented that while they still needed to work on having these conversations with their peers, the case helped them recognize the important role they played in identifying struggling colleagues. During feedback/debrief segment, faculty noted the most common discussion points were interns’ role as a professional, when to use diagnostic tools with a colleague, how to assess the acuity of the situation, confidentiality, and resources/policy on mental health visits.

DISCUSSION

While many residency programs have built wellness programs and have augmented their mental health resources for house staff, we know of no other efforts to use OSCEs to assess and educate residents on intervening with struggling peers. These assessments of interns’ performance identified the need to encourage interns to recognize and explore risk with their troubled peers just as they would with patients. Anecdotally, we have noted an increase in house staff reporting their concerns about their colleagues to program leadership since this case began in 2014. Our medicine program has expanded this OSCE to include incoming chief residents because of the unique role they play in house staff well-being.14

This one OSCE station functioned as a highly visible way to raise awareness about this issue for both house staff and faculty. It demonstrated, to our community, a willingness to use limited curricular time to engage in conversation with each and every intern who went through this station. Perhaps most importantly, the OSCE case served as a catalyst for action, leading to identification, further development, and dissemination of resources and policies, and helped reinforce the responsibility the residency community and the institution have to care for its members. Faculty members’ role modeled a willingness to discuss this sensitive topic and, in so doing, normalized the existence of these issues.

While most residents were empathic and explored their colleague’s emotional state, only a minority performed an appropriate mental health and substance use assessment and/or directed the colleague towards specific resources for his depression—and these rates were similar over time and across residency programs. We found that residents who screen for depression were more likely to refer their colleague for additional help. Knowing when to use newly minted skills is a challenge. It is likely that many more interns would have conducted a depression screen and asked about the quantity and frequency of drinking if presented with a patient with similar complaints. Understanding when to utilize skills outside of the patient-doctor relationship is an important part of a physician’s professional development and should be addressed during training.

There are several limitations to the generalizability of our experience with this curriculum and intervention. We implemented this at only a single institution, and with only a small number of learners and residency programs. The impact of this single experiential learning event during the internship year on both individual interns and residency program culture may not be sustained. Finding sufficient time for high-quality debriefing also proved to be challenging and should be a high priority when designing the OSCE.

Finally, we believe that the ideal way to achieve lasting impact is to use this highly motivating and activating educational innovation as the foundation for integrating additional material, discussions, and practice opportunities and feedback throughout residency training. We are monitoring for longer term impact. In the future, we will study the impact of this new curriculum by comparing responses on annual residency programs’ and faculty surveys before and after its implementation. In these surveys, we will assess for changes in attitude, knowledge of resources for struggling learners and quantifying the number of times concerns about residents have been escalated to program leadership, and if utilization of support services has increased since the introduction of this program.

CONCLUSION

Internship is a critical time for forming one’s professional identity. This OSCE case provided interns and faculty an opportunity to clarify the physician’s role in ensuring the well-being of their colleagues, equipped interns with the skills and knowledge necessary for helping that struggling colleague, and reinforced the need for available resources and clear policies and processes for accessing them. Moreover, it demonstrated leadership’s awareness of these issues and reinforced culture change efforts. Finally, our experience with this “struggling colleague” case suggests that curricula in this area must include recognition of interns’ role conflict (friend/peer vs diagnostician) and send the message that it is their responsibility to intervene with impaired colleagues both for their own safety as well as that of their patients.

References

Holmes EG, Connolly A, Putnam KT, et al. Taking care of our own: a multispecialty study of resident and program director perspectives on contributors to burnout and potential interventions. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):159–66.

Ripp JA, Privitera MR, West CP, et al. Well-being in graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):914–17.

Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3161–66.

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373–83.

Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):557–65.

McNamara RM, Margulies JL. Chemical dependency in emergency medicine residency programs: perspective of the program directors. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(5):1072–76.

Velez N, Cohen S. Medical intern plunges to death off tower in NYC. The New York Post. http://nypost.com/2014/08/22/medical-intern-jumps-to-death-in-nyc/. Published August 22, 2014. Accessed November 1, 2018.

Sinha P. Why Do Doctors Commit Suicide? The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/05/opinion/why-do-doctors-commit-suicide.html?_r=0. Published September 4, 2014. Accessed November 1, 2018.

Tran, Elaine M., Ingrid U. Scott, Melissa A. Clark, and Paul B. Greenberg. Assessing and Promoting the Wellness of United States Ophthalmology Residents: A Survey of Program Directors. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(1):95–103.

Zaver F, Battaglioli N, Deng W, et al. Identifying Gaps and Launching Resident Wellness Initiatives: The 2017 Resident Wellness Consensus Summit. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):342–45.

Sofka S, Grey C, Lerfald N, Davisson L, Howsare J. Implementing a universal well-being assessment to mitigate barriers to resident utilization of mental health resources. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1): 63–66.

Winkel AF, Honart AW, Robinson A, Jones AA, Squires A. Thriving in scrubs: a qualitative study of resident resilience. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):53.

Farrell, CM. A Physician’s Suffering—Facing Depression as a Trainee. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):749–50

Horlick M, Cocks P, Altshuler L, Gillespie C, Zabar, S. Residency Wellness: Changing Culture Through Experiential Learning. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:S840-S840.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the valuable contributions of the inter-professional members of the Research on Medical Education Outcomes (ROMEO) group, our dedicated faculty, standardized patients, and learners, all who participated in creating a supportive learning environment. We acknowledge that The New York Simulation Center for the Health Sciences (NYSIM), a Partnership of The City University of New York and NYU Langone Health, provided material support of staff, space and equipment for the research conducted in this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Oral Presentation at The Society of General Internal Medicine Toronto, ON Canada, April 22–25, 2015

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zabar, S., Hanley, K., Horlick, M. et al. “I Cannot Take This Any More!”: Preparing Interns to Identify and Help a Struggling Colleague. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 773–777 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04886-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04886-y