Abstract

BACKGROUND

The majority of patients who die in hospital have a “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR) order in place at the time of their death, yet we know very little about why some patients request or agree to a DNR order, why others don’t, and how they view discussions of resuscitation status.

METHODS

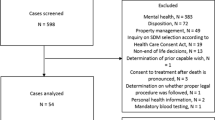

We conducted semi-structured interviews of English-speaking medical inpatients who had clearly requested a DNR or full code (FC) order after a discussion with their admitting team, and analyzed the transcripts using a modified grounded-theory approach.

RESULTS

We achieved conceptual saturation after conducting 44 interviews (27 DNR, 17 FC) over a 4-month period. Patients in the DNR group were much older than those in the FC group, but they had broadly similar admission diagnoses and comorbidities. DNR patients reported much greater familiarity with the subject and described a more positive experience than FC patients with their resuscitation discussions. Participants typically requested FC or DNR orders based on personal, relational or philosophical considerations, but these considerations manifested differently depending on the participant’s preference for resuscitation. Most FC patients stated that would not want a prolonged period of life support, and they would not want resuscitation in the event of a poor quality of life. FC and DNR patients understood resuscitation and DNR orders differently. DNR patients described resuscitation in graphic, concrete terms that emphasized suffering and futility, and DNR orders in terms of comfort or natural processes. FC patients understood resuscitation in an abstract sense as something that restores life, while DNR orders were associated with substandard care or even euthanasia.

CONCLUSION

Our study identified important differences and commonalities between the perspectives of DNR and FC patients. We hope that this information can be used to help physicians better understand the needs of their patients when discussing resuscitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591–8.

Heyland DK, Frank C, Groll D, et al. Understanding cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making: perspectives of seriously ill hospitalized patients and family members. Chest. 2006;130(2):419–28.

Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):1–12.

Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld LA, et al. End-of-life care for the critically ill: A national intensive care unit survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2547–53.

Golin CE, Wenger NS, Liu H, et al. A prospective study of patient-physician communication about resuscitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S52–60.

Smith AK, Ries AP, Zhang B, Tulsky JA, Prigerson HG, Block SD. Resident approaches to advance care planning on the day of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1597–602.

Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(6):441–9.

Fischer GS, Tulsky JA, Rose MR, Siminoff LA, Arnold RM. Patient knowledge and physician predictions of treatment preferences after discussion of advance directives. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(7):447–54.

White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR. Prognostication during physician-family discussions about limiting life support in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):442–8.

Selph RB, Shiang J, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, White DB. Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1311–7.

White DB, Braddock CH 3rd, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):461–7.

Terry M, Zweig S. Residents talk about end-of-life issues. J Long Term Care Adm. 1994;22(3):11–5.

Sinuff T, Cook DJ, Giacomini M. How qualitative research can contribute to research in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2007;22(2):104–11.

Eliott JA, Olver IN. The implications of dying cancer patients' talk on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(4):442–55.

Olver I, Eliott JA. The perceptions of do-not-resuscitate policies of dying patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(4):347–53.

Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients' preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):545–9.

Covinsky KE, Fuller JD, Yaffe K, et al. Communication and decision-making in seriously ill patients: findings of the SUPPORT project. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S187–93.

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73.

Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134(4):835–43.

Chen YY, Connors AF Jr, Garland A. Effect of decisions to withhold life support on prolonged survival. Chest. 2008;133(6):1312–8.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Garrouste-Orgeas M, et al. Decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapy in ICU patients independently predict hospital death. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(11):1895–901.

Prendergast TJ, Claessens MT, Luce JM. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(4):1163–7.

Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the "planning" in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–U274.

Tulsky JA, Chesney MA, Lo B. How do medical residents discuss resuscitation with patients? J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(8):436–42.

Heyland DK, Allan DE, Rocker G, Dodek P, Pichora D, Gafni A. Discussing prognosis with patients and their families near the end of life: impact on satisfaction with end-of-life care. Open Med. 2009;3(2):e101–10.

White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR. The language of prognostication in intensive care units. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(1):76–83.

Alexander SC, Keitz SA, Sloane R, Tulsky JA. A controlled trial of a short course to improve residents' communication with patients at the end of life. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):1008–12.

Lorin S, Rho L, Wisnivesky JP, Nierman DM. Improving medical student intensive care unit communication skills: a novel educational initiative using standardized family members. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2386–91.

Downar J, Hawryluck L. What should we say when discussing "code status" and life support with a patient? A Delphi analysis. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(2):185–95.

Eliott JA, Olver IN. Dying cancer patients talk about euthanasia. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(4):647–56.

Rosenfeld B. Assisted suicide, depression, and the right to die. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2000;6(2):467–88.

Low JA, Pang WS. Is euthanasia compatible with palliative care? Singapore Med J. 1999;40(5):365–70.

Luce JM, Alpers A. End-of-life care: what do the American courts say? Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2 Suppl):N40–5.

Burns JP, Edwards J, Johnson J, Cassem NH, Truog RD. Do-not-resuscitate order after 25 years. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1543–50.

Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953–63.

White DB, Evans LR, Bautista CA, Luce JM, Lo B. Are physicians' recommendations to limit life support beneficial or burdensome? Bringing empirical data to the debate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(4):320–5.

Layde PM, Beam CA, Broste SK, et al. Surrogates' predictions of seriously ill patients' resuscitation preferences. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(6):518–23.

Zhukovsky DS, Hwang JP, Palmer JL, Willey J, Flamm AL, Smith ML. Wide variation in content of inpatient do-not-resuscitate order forms used at National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers in the United States. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(2):109–15.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Funding Source

Associated Medical Services, Incorporated provided financial assistance in the form of a fellowship grant to three of the authors (JD, JM, and HB). This money was used to pay for recording equipment and professional transcription services.

Statement of Submitting Author

JD has had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

JD, RWS, JM, and LH all contributed to study design. JD and TL conducted literature searches. JD, TL, and RWS conducted the interviews and analyzed the data. All authors participated in data interpretation. JD wrote the original manuscript, and all authors participated in critical revision.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Downar, J., Luk, T., Sibbald, R.W. et al. Why Do Patients Agree to a “Do Not Resuscitate” or “Full Code” Order? Perspectives of Medical Inpatients. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 582–587 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1616-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1616-2