Abstract

BACKGROUND

Poor communication between referring clinicians and specialists may lead to inefficient use of specialist services. San Francisco General Hospital implemented an electronic referral system (eReferral) that facilitates iterative pre-visit communication between referring and specialty clinicians to improve the referral process.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of the study was to determine the impact of eReferral (compared with paper-based referrals) on specialty referrals.

DESIGN

The study was based on a visit-based questionnaire appended to new patient charts at randomly selected specialist clinic sessions before and after the implementation of eReferral.

PARTICIPANTS

Specialty clinicians.

MAIN MEASURES

The questionnaire focused on the self-reported difficulty in identifying referral question, referral appropriateness, need for and avoidability of follow-up visits.

KEY RESULTS

We collected 505 questionnaires from speciality clinicians. It was difficult to identify the reason for referral in 19.8% of medical and 38.0% of surgical visits using paper-based methods vs. 11.0% and 9.5% of those using eReferral (p-value 0.03 and <0.001). Of those using eReferral, 6.4% and 9.8% of medical and surgical referrals using paper methods vs. 2.6% and 2.1% were deemed not completely appropriate (p-value 0.21 and 0.03). Follow-up was requested for 82.4% and 76.2% of medical and surgical patients with paper-based referrals vs. 90.1% and 58.1% of eReferrals (p-value 0.06 and 0.01). Follow-up was considered avoidable for 32.4% and 44.7% of medical and surgical follow-ups with paper-based methods vs. 27.5% and 13.5% with eReferral (0.41 and <0.001).

CONCLUSION

Use of technology to promote standardized referral processes and iterative communication between referring clinicians and specialists has the potential to improve communication between primary care providers and specialists and to increase the effectiveness of specialty referrals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Effective specialty care depends on adequate communication between primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists. Most referrals rely on verbal and paper-based methods.1–4 Referrals suffer from vague consult questions3, inadequate pre-referral investigation4 and delayed communication.5–10 Whereas effective communication may reduce unnecessary or premature referrals11, poor communication contributes to physician dissatisfaction5, ambiguous expectations, delayed diagnoses, duplication of testing and fragmented care4,6, and adverse outcomes.12,13

The use of health information technology (HIT) has been associated with improved safety, efficiency and quality of health care.14–17 Innovative uses of HIT in coordinating specialty care may facilitate communication and effective access.2,5,18–21 Uptake of HIT systems has been slowed by high start-up costs, initial decreases in workplace productivity, unrealistic expectations and technological challenges.22,23 These barriers may be disproportionately experienced in the safety-net; however, if successful, HIT could reduce disparities by enabling broader access to health care.

We created and implemented an electronic referral and consultation system (eReferral) at San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (SFGH). eReferral uses a web-based program embedded in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate a structured review process for new specialty clinics referrals. eReferral allows for iterative communication between the referring provider and a specialist reviewer prior to or in lieu of new patient specialty appointments. We previously demonstrated that referring clinicians were highly satisfied with eReferral.2 In order to assess the impact of eReferral on the experiences of specialist clinicians, we conducted an encounter-based survey that examined the specialist’s perception of the quality and adequacy of communication, comparing referrals made through eReferral with those referred via paper-based methods. We hypothesized that clinicians seeing patients referred via eReferral would report lower levels of difficulty understanding the consultative question, lower rates of inappropriate referrals and lower rates of avoidable follow-up visits.

METHODS

Setting

Beginning in July 2005, SFGH, a city and county hospital staffed by University of California San Francisco physicians, implemented eReferral to improve the process of specialty referrals. SFGH is the main provider of specialty care for the uninsured and underinsured in San Francisco. SFGH and its affiliated clinics use a hybrid paper and EHR documentation system. Once a clinic adopts eReferral, it becomes the only mechanism for new patient referrals. We examined adult medical specialty clinics that were in the process of adopting eReferral: cardiology and pulmonary (January 2007), endocrinology and rheumatology (May 2007) and renal (January 2008); as well as two surgical specialty clinics, neurosurgery and orthopedics (July 2007).

Description of Referral Processes

Prior to eReferral, non-emergent referrals for specialty appointments were managed using a paper-based system. Referring providers filled out forms which were faxed or hand-carried to the specialty clinic. In all but two specialty clinics, clerical staff assigned these appointments on a first-received, first-scheduled basis. If a referring clinician needed an appointment sooner than offered, he or she could page the on-call subspecialty resident or fellow to request permission to “overbook” the patient.

With eReferral, referring clinicians use a web-based application that is integrated with SFGH’s EHR, the Siemens Invision/Lifetime Clinical Record. Referring providers initiate an electronic form that is populated with their contact information and the patient’s contact, demographic and clinical data from the EHR. A free text field is provided to enter the reason for consultation and pertinent clinical information. (See Fig. 1) A designated specialty reviewer (a physician specialist in medical specialties or a nurse practitioner in surgical specialties) reviews the referrals. Reviewers adjudicate each referral within 72 hours of submission and decide to either schedule or not schedule an appointment. If the reviewer deems that the appointment is necessary and there is sufficient information for the specialist seeing the patient to make a clinical decision, the appointment is scheduled. The reviewer can request the next available regular appointment or an expedited appointment. When the clinical question is not clear, the necessary work-up is not completed or the problem can be handled in the primary care setting, an appointment is not scheduled. The reviewer can ask for clarifying information, guide further evaluation or provide education as to how the referring provider can manage the issue. Referring and reviewing clinicians can communicate via eReferral in an iterative fashion until both agree that the patient does not need the appointment or the appointment is scheduled. (Fig. 2) All correspondence is conducted within eReferral and captured in the patient’s EHR. At the time of a specialty visit, the electronic referral form is printed and available to the specialty clinician as a hardcopy.2

In prior work that examined referring clinicians eligible to use eReferral, we found that 53.5% were attending physicians, 22.9% were nurse practitioners, and 23.6% were residents.2 The number of referrals for different specialties varied between 20 and 250 referrals per month. Reviewers spent between 5 and 15 minutes on each referral request and between 1 and 6 hours a week reviewing. During the study period, reviewers’ time was paid for by a grant.

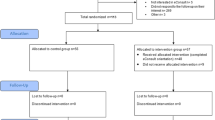

Study Participants

After calculating our sample size, we determined the number of questionnaires to collect per specialty depending on patient volume. For each specialty clinic, we selected different time periods to distribute the questionnaire so that approximately half of sessions would be when patients were referred via the paper-based system and half via eReferral. Within these time periods, we selected specific clinic dates randomly. For paper-based responses, we selected dates prior to when eReferral was being initiated. For eReferral responses, we chose dates far enough after the adoption of eReferral so that the majority of new patient appointments would have been scheduled via eReferral. Because of scheduling backlogs, we waited to administer post-eReferral questionnaires until the majority of new patients would have been referred via eReferral (up to 6 months after initiation of eReferral). We defined a new patient visit as the first time the patient was seen in that clinic in the past two years. We asked the first clinician who saw a new patient during randomly selected clinic sessions to fill out the questionnaire. If the first clinician to see the patient was a medical student, we excluded the response from the study.

Survey

Survey Method

We developed a 6-item paper-based questionnaire to assess the appropriateness of each specialty clinic visit and the adequacy of information about the clinical question and pre-visit work-up. Research or clinic staff appended questionnaires to patient charts for all eligible new-patient appointments during the selected clinic sessions. Questionnaires did not require the specialty provider to reveal any self-identifying information other than his/her level of training. We instructed clinicians to leave completed questionnaires in a collection envelope that study staff collected at the conclusion of each session.

For each participating clinic, research assistants attended the first 5–10 clinic sessions to answer any procedural questions; we did not share the study hypotheses. After the initial visits, study staff provided intermittent education about the survey to encourage participation. In order to calculate response rate, we randomly selected 1–3 clinic sessions in which we distributed the questionnaire for each specialty clinic. We compared the proportion of surveys returned to the known number of new patients seen during that session. We received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco.

Questionnaire Content

Participants first identified their level of training (medical student, resident, fellow, nurse practitioner/physician’s assistant, attending or other) and specified whether the patient was referred via eReferral, non-eReferral method (paper-based) or not known. Clinicians rated the difficulty of identifying the reason for the consultation as very difficult, somewhat difficult, or not difficult at all and rated the appropriateness of the referral as completely appropriate, somewhat appropriate, or not appropriate. Clinicians responded whether she or he would recommend a follow-up visit for the patient and if so, whether or not the follow-up visit could have been avoided if there had been a more complete work-up prior to the initial appointment. All responses were based on the clinical judgment of the specialist; we did not provide definitions of difficulty in identifying the reason for referral or the appropriateness of referral.

Statistical Analysis

In the data analysis, we divided data from all completed questionnaires into two specialty categories: medical and surgical specialty groups. We used the new patient visit as the unit of analysis.

Regarding the mode of referral, we grouped “don’t know,” with paper-based referrals because all “don’t know” responses occurred before the initiation of eReferral. We collapsed “somewhat difficult” and “very difficult” as difficult. We collapsed “completely appropriate” and “somewhat appropriate” responses into the appropriate category in recognition that there is a range of appropriateness that may require further specialty evaluation.

We analyzed data from the medical and surgical specialty groups separately. For each questionnaire item, we compared the proportions of positive or negative clinician response for referrals made via paper-based methods with the proportions of responses for referrals made by eReferral. We measured statistical significance using Fisher’s exact test for 2 by 2 contingency tables, with a p-value threshold set at 0.05. We used simple descriptive statistics to characterize the participants and their responses.

RESULTS

We collected 540 questionnaires, 335 from medical and 205 from surgical clinics. We excluded 26 responses for medical clinics and nine responses for surgical clinics because they were completed by medical students, leaving 309 referrals from medical specialties and 196 referrals from surgical specialties for analysis. Referrals made through eReferral constituted 58.9% of all questionnaires collected from medical specialty clinics and 48.5% of questionnaires from surgical specialty clinics. Spot checks of clinics yielded an average response rate of over 70%; no clinic had an overall response rate less than 70%.

Questionnaires in the medical specialty clinics were completed by fellows (52.4%), attending physicians (28.2%) or resident physicians (18.8%). Questionnaires in the surgical specialty clinics were completed by residents (59.2%), mid-level providers (25.0%) or attending physicians (13.3%). The proportions did not vary depending on whether the referrals were paper-based or via eReferral (Table 1).

Dependent Variables

Difficulty in Identifying Clinical Question

Medical specialty clinicians reported difficulty identifying the reason for consultation or clinical question in 19.8% of new patient visits referred via the paper-based method vs. 11.0% of new patient visits referred using eReferral (p-value 0.03). In surgical specialty clinics, clinicians reported difficulty in 38.0% (paper-based) vs. 9.5% (eReferral) of visits (p-value <0.001, Table 2).

Appropriateness of Referral

Medical specialty clinicians considered the referral inappropriate for 6.4% of new patients referred via paper-based methods vs. 2.6% of new patients referred by eReferral (p-value 0.21). Surgical specialty clinicians considered the referral to be inappropriate for 9.8% (paper-based methods) vs. 2.1% (eReferral) of visits (p-value 0.03, Table 2).

Need for Follow-up

Medical specialty clinicians indicated that they requested follow-up for 82.4% of new patient visits referred via paper-based methods and 90.1% of new patient visits referred by eReferral (p-value 0.06). In surgical specialty clinics, clinicians indicated that they requested follow-up for 76.2% (paper-based) and 58.1% (eReferral) of visits (p-value 0.01, Table 2).

Avoidability of Follow-up

Of those cases that required a follow-up visit, medical specialty clinicians considered 32.4% of follow-up requests resulting from paper-based methods referrals and 27.5% of follow-up requests resulting from referrals by eReferral to be avoidable if a more complete workup had been done prior to the specialty visit (p-value 0.41). Surgical specialty clinicians considered 44.7% (paper-based) and 13.5% (eReferral) of follow-up requests to be avoidable (p-value <0.001, Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Most PCPs and specialists in the United States communicate with each other through referral letters, without pre-visit consultation. In this study, we compared visit-based questionnaires filled out by specialists before and after the initiation of a novel electronic referral and consultation system (eReferral). eReferral facilitated communication between referring clinicians and a specialist reviewer prior to the appointment. We found that with paper-based referrals, specialists had difficulty identifying the clinical question. In surgical specialties, there was higher percentage of inappropriate referrals and need for unnecessary follow-up. The adoption of eReferral was associated with improvements in these. Differences were more pronounced for the surgical than for the medical subspecialty clinics.

For referrals made via eReferral, specialists reported higher rates of being able to determine the clinical question. Specialists’ difficulty understanding the consultative question provides insight into a failure of primary care-specialist collaboration. Despite its importance in providing effective specialty care4–6 and its impact on health outcomes13, the frequency and quality of information exchanged between PCPs and specialists is often inadequate.4,9,18 One study examining PCP-specialist communication using paper-based referrals found that 24% of referrals did not include an explicit consultation question.3 With eReferral, the use of HIT facilitated iterative communication and allowed specialty reviewers to clarify the consultative question by requesting additional information prior to scheduling an appointment. The electronic system also ensured that referring information was available and legible at the appointment. Despite these improvements, in approximately 10% of eReferrals, the reason remained difficult to ascertain. This finding may reflect different standards as to what constitutes a clear consultative question or may represent that reviewers decided to schedule the patient for an appointment rather than attempt to further clarify the clinical question. Our data cannot distinguish between these possibilities.

We also found decreases in the proportion of referrals deemed to be inappropriate in surgical clinics. Our findings suggest that eReferral may be an effective way to prevent inappropriate referrals from resulting in appointments in surgical clinics, thus saving unproductive visits. In surgical clinics, after the adoption of eReferral fewer new appointments required follow-up visits and of those, fewer were deemed to be avoidable. The iterative pre-visit communication may be responsible for this observation. Prior studies have shown that direct communication with specialist consultants has the potential to decrease unnecessary visits. In one study, generalists felt that 33% of all referrals could have been avoided if they had training in simple procedures or been able to speak with a specialist.11 eReferral was designed to provide an alternative to formal consults for some cases.

eReferral changes the work flow of all involved: for referring providers, instead of handwriting a referral and handing it to a medical assistant for processing, he or she enters the electronic referral via the EHR. In a significant proportion of cases, the referring provider, upon receiving the reviewer’s response, must obtain additional history or tests prior to the appointment being scheduled. Sometimes the referring provider manages the problem without a specialty visit, with guidance via the eReferral specialist reviewer. In a complementary study completed by our research group, we found that PCPs reported that specialists offered better pre-referral guidance and addressed the clinical question more effectively with electronic referrals than with paper-based methods.2 While specialist reviewers were paid by a grant during the study, the hospital now compensates them for their time spent reviewing.

This study contained several limitations. Our study’s design relied on a comparison of responses before and after the initiation of a new system; the pre-post design limits our ability to determine causality. We determined the impact of eReferral on the referral process solely based on specialty clinicians’ perceptions, rather than objective criteria. However, given the clinical heterogeneity of the disease states being cared for across specialty clinics, the use of more clinically-detailed criteria was not feasible. The study included specialty clinicians with a broad range of clinical expertise and comfort in dealing with issues encountered in specialty care. Thus, their judgments may have been affected by their level of training. However, this level of training did not differ substantially before and after the intervention. It is possible that some specialty clinicians filled out questionnaires on more than one visit, but we could not adjust for clustering. We do not know the training level of referring clinicians, but we do not have reason to believe that proportions are different between paper-based referrals versus eReferrals. Non-response could have introduced bias. However, our response rates were over 70% and specialist clinicians were not aware of study aims or hypotheses. Our study has several strengths. We evaluated the initiation of a comprehensive use of Health IT in a complex safety-net system, rather than a pilot study among early adopters. We have included a diverse set of specialty clinics to expand generalizability. The referring clinics were also diverse, staffed by a wide range of health care providers from different disciplines and training background and different organizational structures. The uptake and use of eReferral by referring providers and specialists attests to the system’s perceived functionality and usability.24 Because the survey is encounter based, recall or response bias is less likely.

HIT, used in this manner, represents an important opportunity to improve PCP-specialist communication by facilitating communication prior to specialty appointments. In current specialty care practice, specialists share management roles with primary care physicians20, but few models of shared care use computer-based systems effectively.19 Effective communication would not require electronic systems, but eReferral used computer technology to integrate referring provider’s requests with the EHR, to automate the routing of messages, and to send email reminders to referring providers. The delivery of high-quality specialty care requires clear and consistent communication between referring and specialty clinicians throughout the referral process.21 Lapses in communication result in iatrogenic complications, redundant testing and delayed diagnosis among other negative consequences in specialty care.4,6 An electronic referral system that allows a specialist reviewer to triage, clarify the consultative question, provide recommendations and to guide pre-visit evaluation can increase the appropriateness and effectiveness of specialty care.

References

Chen AH, Yee HF Jr. Improving the primary-specialty care interface: getting from here to there. Arch Int Med. 2009;169:1–3.

Kim Y, Chen AH, Keith E, Yee HF Jr, Kushel MB. Not perfect, but better: primary care providers’ experiences with electronic referrals in a safety net health system. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):614–9.

McPhee SJ, Lo B, Saika GY, Meltzer R. How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Arch Intern Med. 1984;144(6):1265–8.

Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, Sussman AJ, Fairchild DG, Bates DW. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):626–31.

Wood ML. Communication between cancer specialists and family doctors. Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:49–57.

Epstein RM. Communication between primary care physicians and consultants. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(5):403–9.

Navaneethan SD, Aloudat S, Singh S. A systematic review of patient and health system characteristics associated with late referral in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:3.

Forrest CB, Glade GB, Baker AE, Bocian A, von Schrader S, Starfield B. Coordination of specialty referrals and physician satisfaction with referral care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(5):499–506.

Stille CJ, McLaughlin TJ, Primack WA, Mazor KM, Wasserman RC. Determinants and impact of generalist-specialist communication about pediatric outpatient referrals. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1341–9.

Rosser JE, Maguire P. Dilemmas in general practice: the care of the cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(3):315–22.

Donohoe MT, Kravitz RL, Wheeler DB, Chandra R, Chen A, Humphries N. Reasons for outpatient referrals from generalists to specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):281–6.

Levin A. Consequences of late referral on patient outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(Suppl 3):8–13.

Olivotto IA, Gomi A, Bancej C, et al. Influence of delay to diagnosis on prognostic indicators of screen-detected breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94(8):2143–50.

Jha AK, Ferris TG, Donelan K, et al. How common are electronic health records in the United States? A summary of the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(6):w496–507.

Leu MG, Cheung M, Webster TR, et al. Centers speak up: the clinical context for health information technology in the ambulatory care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):372–8.

Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2526–34.

Simon SR, Kaushal R, Cleary PD, et al. Physicians and electronic health records: a statewide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):507–12.

Bergus GR, Emerson M, Reed DA, Attaluri A. Email teleconsultations: well formulated clinical referrals reduce the need for clinic consultation. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(1):33–8.

Smith SM, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Does sharing care across the primary-specialty interface improve outcomes in chronic disease? A systematic review. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(4):213–24.

Wegner SE, Lathren CR, Humble CG, Mayer ML, Feaganes J, Stiles AD. A medical home for children with insulin-dependent diabetes: comanagement by primary and subspecialty physicians-convergence and divergence of opinions. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e383–7.

Stille CJ, Jerant A, Bell D, Meltzer D, Elmore JG. Coordinating care across diseases, settings, and clinicians: a key role for the generalist in practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):700–8.

Pizzi LT, Suh DC, Barone J, Nash DB. Factors related to physicians’ adoption of electronic prescribing: results from a national survey. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(1):22–32.

Crosson JC, Isaacson N, Lancaster D, et al. Variation in electronic prescribing implementation among twelve ambulatory practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):364–71.

Palm JM, Colombet I, Sicotte C, Degoulet P. Determinants of user satisfaction with a Clinical Information System. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006;614–618.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ellen Keith for her assistance in managing the project. We thank Kuan-Lung Daniel Chen, Lynette LC Chen, Theo A. Yonn-Brown, and Patricia Hom for their assistance with distributing and collecting questionnaires.

Funding

Drs. Chen, Bell, Yee and Kushel and Mr. Guzman received funding from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, through contract # HHSA290200600017, Task Order No. 3. Drs. Chen, Yee and Kushel and Mr. Guzman received funding from the San Francisco Health Plan. Dr. Yee was partially funded by the William and Mary Ann Rice Memorial Distinguished Professorship.

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Chen and Yee note that they have served as independent consultants for public, non-profit organizations interested in implementing the UCSF/SFGH eReferral model. No other authors report any conflicts or financial interests.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim-Hwang, J.E., Chen, A.H., Bell, D.S. et al. Evaluating Electronic Referrals for Specialty Care at a Public Hospital. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 1123–1128 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1402-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1402-1