Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Monitoring and modifying physicians’ prescribing behavior through prescription tracking is integral to pharmaceutical marketing. Health information organizations (HIOs) combine prescription information purchased from pharmacies with anonymized patient medical records purchased from health insurance companies to determine which drugs individual physicians prefer for specific diagnoses and patient populations. This information is used to tailor marketing strategies to individual physicians and to assess the effect of promotions on prescribing behavior.

DISCUSSION

The American Medical Association (AMA) created the Prescription Data Restriction Plan in an attempt to address both the privacy concerns of physicians and industry concerns that legislation could compromise the availability of prescribing data. However, the PDRP only prohibits sales representatives and their immediate supervisors from accessing the most detailed reports. Less than 2% of US physicians have registered for the PDRP, and those who have signed up are not the physicians who are targeted for marketing.

CONCLUSION

Although it has been argued that prescription tracking benefits public health, data gathered by HIOs is designed for marketing drugs. These data are sequestered by industry and are not generally available for genuine public health purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Pharmaceutical companies track prescriptions to develop and evaluate general marketing efforts and to tailor sales pitches to individual physicians.1 The information is also used to allocate samples, to design continuing medical education programs and direct-to-consumer campaigns, and to evaluate the effects of specific promotions on sales. Internally, pharmaceutical companies use prescription tracking to identify physicians to target, to delineate sales force territories, and to evaluate and compensate sales representatives who receive bonuses based on drug sales in their area.2,3

Prescription information is collected by health information organizations (HIOs), which have monitored prescriptions via surveillance technologies since the 1950s.4 Access to information regarding the prescriptions of individual physicians has been available since 1989.5 HIOs, also known as data-mining companies, act as brokers of this information, which they package from different sources to create detailed prescribing portraits of each physician. IMS Health is the largest HIO; others include Dendrite, Verispan, and Wolters Kluwer.6

Pharmacies, the primary source of prescribing data, sell patients’ prescription records that include the date, medication name, dose, and directions. Specific unique numbers are substituted for patient names. Prescribers are identified by number (usually state license or Drug Enforcement Administration numbers). IMS obtains records on about 70% of prescriptions filled in community pharmacies.6 Prescription information is also obtained from pharmacy benefit managers and wholesalers.3

In the United States, HIOs are able to reassociate physician identifiers with physician names by purchasing information from the American Medical Association (AMA), which maintains the Physician’s Masterfile, a database that contains demographic information on all U.S. physicians.6 Currently, the Masterfile includes approximately 900,000 M.D.s and D.O.s in the United States.7 According to a company that licenses Masterfile data, the AMA also receives “student information from medical schools, residency information from residency program directors, and practice information from over 2,100 different resources including medical organizations, institutions and government agencies.”8 The AMA has sold doctors’ demographic data to the pharmaceutical industry continuously since the 1940s.4

In contrast, Canada, Europe, and many other countries do not allow industry access to information on each physician’s prescriptions. Prescribing data for groups of physicians (known as “bricks”) are available, but not for individual physicians.2

In the U.S., not only are individual physicians’ prescriptions minutely monitored, but so are their patients’ medical records. Although patient names are not included, information gathered on individuals may include age, sex, geographic location, medical conditions, hospitalizations, laboratory tests, insurance copays, and medication use.9 Although detailed information is tracked on individuals over time, this commercial use of medical records complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), a federal statute that provides some medical privacy protections, because patient names are not included. Instead, unique numbers identify each individual.9

PharMetrics, a unit of IMS, has a database that “contains >2 [billion] health care events including the complete set of pharmacy and medical claims of >55 million Americans.”10 “Anonymized patient-level data” refines industry knowledge of physicians’ prescribing behavior by revealing “first- and second-line usage, diagnosis, compliance/persistency, and referral patterns.”11 Patient-level data “can help marketers understand which strategy will have the greatest effects on sales.”11

In other words, the linkage of medical claims with prescription data allows HIOs to offer pharmaceutical companies detailed information on every physician’s referral networks, patients, and preferred treatments for specific diagnoses in specific patient subpopulations. These data, usually updated on a weekly basis, allow ongoing analyses of how a physician’s prescribing behavior responds to personally tailored marketing strategies.

THE PDRP

In recent years, prescription tracking has become a controversial issue among physicians. Several state legislatures have introduced bills restricting prescription tracking. The AMA met with industry and surveyed physicians, finding that although two-thirds of physicians opposed the availability of prescribing data to drug representatives, 77% of those would have their concerns alleviated if doctors could choose to protect their individual prescribing information.3

In response to industry and physician concerns, the AMA created the Prescription Data Restriction Plan (PDRP). Interested physicians visit a website (http://www.ama-assn.org/go/prescribingdata) and fill out a form requesting that their prescribing data be withheld from pharmaceutical sales representatives. To activate one’s PDRP rights online, a physician must check off or provide a reason for opting out and accept the vaguely ominous statement that, “Some of the information provided may be shared with entities outside the AMA in order to register and/or follow up on your concern.” Requests expire 3 years from when the physician signs up, and requests may take 6 months to take effect because drug companies are required to check the list quarterly and then have 90 days to restrict sales representatives access to these data.12

A pilot version of the PDRP was launched in California and several other states in May 2006; the program officially launched nationally in July 2006.7

Few doctors know about the PDRP. Soon after the program launched, a poll of 210 physicians found that only 18% were aware of the program; more than half (53%) were interested in signing up.13

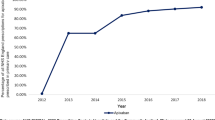

The AMA mailed no announcements to physicians because studies have shown that “direct mail to physicians is very inefficient,” according to the AMA’s Media Outreach Coordinator,7 who also noted that office staff often intercept physicians’ mail. Instead, the AMA placed ads or announcements in AMA publications and several medical journals, and e-mailed announcements to about 100,000 physicians, about 1,000 of whom subsequently signed up for the PDRP.7 By July 18, 2006, 2,900 of 800,000 practicing physicians had signed up for the PDRP.13 By May 2007, a year after the program began, about 1% of active physicians (7,476) doctors had opted out.14 By January 2008, almost 12,000 doctors (65% of whom are not AMA members) have signed up.15

Such low participation in the PDRP is predictable because opt-out options “are designed to maximize participation while preserving a patina of choice.”16 Default choices are perceived to be socially preferable, so opt-out options have resulted in increased default participation in situations as diverse as prenatal HIV testing, 401(k) savings plans, and medical journal reviewing.16

In its current form, the PDRP withholds some information from some industry representatives some of the time. Individual prescribing information is withheld only from pharmaceutical representatives and their immediate supervisors. All other employees retain full access to all the individual-specific prescribing information. As an industry article puts it, “The information available to the ‘home office’ will not change, regardless of physician enrollment in PDRP. This program will not affect headquarter business systems.”17 The most relevant information is still available to pharmaceutical representatives because the PDRP exempts information on “(a) deciles at the market or therapeutic class level, (b) segmented data that are not likely to reveal the actual or estimated activity of an individual physician, or (c) data on products ordered by physicians from pharmaceutical companies.”17

In other words, the PDRP does not restrict pharmaceutical companies from seeing, analyzing, and using prescribing data to promote specific drugs to the doctors who have opted out. However, the pharmaceutical representatives and managers are still provided the information that Dr. X is in the top 10% of doctors in terms of prescribing volume for antidepressants; in the top 20% for antibiotics; and is an “early adopter” of drugs. Pharmaceutical representatives enjoy full access to drug-specific details on chemotherapy or any other drugs dispensed or administered in physicians’ offices. An industry article notes that that although the PDRP “limits reps and their supervisors from accessing data on some physicians, it nonetheless enable companies to continue to run essential business applications that rely on prescriber data.”17

Whereas a massive physician sign-up of high prescribers for the PDRP would inconvenience pharmaceutical companies, “the opt-outs to date are generally lower-prescribing physicians, with 72% in the market-five decile or lower.”3 Doctors in the bottom half of prescribers are not targeted for marketing anyway.

AN ALTERNATIVE TO LAW

In 2006, New Hampshire passed a law banning commercial sale of prescribing data and was promptly sued by IMS and Verispan. On April 30, 2007, a federal judge ruled the New Hampshire law unconstitutional on the grounds that it restricts commercial free speech.18 The state plans to appeal the decision.

Other states are considering similar bills, but the decision in New Hampshire and the availability of the PDRP has had an effect. A preliminary injunction was granted to prevent enforcement of a Maine law (which is also being appealed), and Vermont is now modifying a law that it passed.15 The availability of the PDRP was key to a 2006 decision not to reintroduce California Assembly Bill 262 (narrowly defeated in 2004), which would have severely restricted the sale and use of prescription data.5

An industry publication explains, “Pharmaceutical manufacturers need to make the PDRP work, since the alternative, government legislation, is not in anyone’s best interest. Without PDRP, long-term access to physician-level data within the healthcare system is called into question.”5 The AMA’s PDRP brochure states that the program “responsibly honors the opinions of all physicians—and provides a more reasonable alternative to a “one-size-fits-all” legislative ban that ignores vital aspects of prescribing data use.”19

The industry-friendly nature of the PDRP is revealed in an article coauthored by AMA and IMS employees, which states, “The rules allow the industry to retain access to prescribing data for most purposes, but they require companies to police their own sales forces. If they succeed, legislators will turn their attention elsewhere, and the industry can hang onto one of its most valuable data sources.”17

RISKS AND BENEFITS OF RX TRACKING

Pharmaceutical interests argue that unrestricted access to prescribing data saves lives, money, and physicians’ time. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) has argued that prescriber data are needed to send out communications informing doctors of drug recalls and serious adverse effects.20 However, when the FDA orders a recall or mandates a new black box warning on a drug, the manufacturer is usually required to send a “Dear Health Care Provider” letter to all U.S. prescribers, not just to those who recently prescribed the drug.

PhRMA also argues that, “Access to prescriber data allows pharmaceutical companies to target necessary prescription information to physicians which helps avoid a saturation of less relevant information to a broader physician audience.”20 An industry article states that, “Prescribing data allow pharmaceutical promotion to be relevant and specific, making the whole process more cost-effective (and sparing physicians from being bombarded with extraneous promotional materials and sales calls)….”17 Certainly, these data enable the identification of physicians relevant and specific to drug sales. Sales calls and promotional materials are preferentially showered on high-prescribing physicians and others who affect market share.1

The AMA, in testimony opposing legislation to restrict industry access to prescriber data, states that, “this information is critical to improving the quality, safety, and efficacy of providing patient care through evidence-based medical research.”21

The AMA is misguided on this point. Researchers do not need HIO data, which are too expensive for most individual researchers to purchase anyway.4 (IMS has occasionally provided limited data to some researchers without cost or at discount.20 Anecdotally, free data are older data and do not contain dates of service or other information routinely provided to paying customers.)

Although HIOs claim that the FDA relies on their data, the use of HIO data by the FDA for public health purposes is trivial. According to IMS’ 2006 Annual Report, “Sales to the pharmaceutical industry accounted for substantially all of our revenue in 2006, 2005, and 2004.”22

It bears noting that HIOs are not the only source of prescription data. Medicare, Medicaid, the military, the Veteran’s Administration, and large health maintenance organizations (HMOs) all have databases of medical and prescription information that have been extensively used by health services researchers. Databases of large HMOs can be used to examine commercially insured populations. The inclusion of race and ethnicity data makes Medicaid ideal for researching health outcomes in diverse populations (Medicaid covers 1 in 5 Americans, including 1 in 3 African Americans and 1 in 4 Latinos).23

Government data may be the most reliable for research purposes. One recent analysis found prescription data available from the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) superior to Medicaid data available from a commercial vendor.24 The coverage of outpatient prescription drugs through Medicare Part D will create a trove of prescription data on elders for researchers.

Public health research rarely requires the identification of individual physicians. HIOs package physicians’ names with prescriptions and patient medical records to facilitate pharmaceutical marketing efforts to manipulate individual prescribing habits.

There is no obligation for HIOs to share information with government regulators—even when such information affects public health. For example, sluggish sales of a migraine drug in 2003 led an unnamed company to hire IMS Health to determine why.25 IMS researchers hypothesized that lower-than-forecasted sales of the migraine drug could be because of decreased menopausal hormone use. Millions of women stopped taking menopausal hormones in mid-2002 when the Women’s Health Initiative showed that risks outweighed benefits for the most popular estrogen–progestin regimen. IMS examined the medical records of 41,403 women with migraines and found that those who stopped hormone therapy halved their use of migraine drug prescriptions. Women filled an average of 2.94 prescriptions for migraine medication during a 6-month period on hormone therapy compared with an average of 1.49 prescriptions during a 6-month period after they stopped hormones. More than half of the women (54%) filled no migraine drug prescriptions in the 6 months after quitting hormones.25

This very large study, which definitively linked migraines and hormone therapy, was never shared with physicians nor published in the medical literature. It was mentioned, in a publication directed exclusively at pharmaceutical marketers, as an example of the services HIOs provide to pharmaceutical companies. What other marketing studies with implications for public health are hidden in industry files? Pharmaceutical companies are required by law to report adverse events associated with their products to the FDA. HIOs should also be required to report adverse effects of therapies they study.

The commercial sale and use of prescriptions and medical records compromises the privacy of individual prescribers and patients, is not necessary for health services research, and may well have adverse effects on public health. The purpose of prescription tracking is to promote the use of the newest, most expensive drugs, a practice that threatens rational prescribing.

Assessment of the benefits and harms of medications should be a government function, implemented by researchers without commercial ties, and conducted solely in the public health interest. Public monies should be allocated to integrate existing public sources of health data and expand accessibility to researchers who will use these data in the interests of patients rather than industry profits.

References

Fugh-Berman A, Ahari S. Following the script: how drug reps influence prescribing. PLoS Med. 2007;4(4):e150. Available at http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040150. Accessed February 25, 2008.

Niles S. No way to fill in the blanks. Med Ad News. 2006;25(5):1–5. May.

Rawson K. Flying blind: learning to live without physician prescribing data. RPM Report. 2007 (January). Windhover Information. Available at http://therpmreport.com/. Accessed February 25, 2008.

Greene JA. Pharmaceutical marketing research and the prescribing physician. Ann Int Med. 2007;146:742–8.

Alonso J, Menzies D. Just what the doctor ordered. Pharm Exec. 2006; (Successful Sales Management Supplement) 26(5):14–6. May.

Steinbrook R. For sale: physicians’ prescribing data. New Engl J Med. 2006;354(26):2745–7.

Telephone interview with Robert Mills, Media Relations, AMA. December 8, 2006 and May 29, 2007.

Medical Marketing Service. Available at http://mmslists.com/main.asp (View lists; Physicians). Accessed March 18, 2007.

Tsang J-P, Rudychev I. The sample equation. Med Mark Media. 2006;41(2):53–8. February.

IMS. IMS Annual Report 2006. Available at http://www.imshealth.com/vgn/images/portal/CIT_40000873/44/9/80649404IMS_2006_AR.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2008.

Nickum C, Brand R. Using integrated data sets to truly differentiate physicians. Product Manag Today. 2005;16(8). September. Available at http://www.PMToday.com.

American Medical Association. Physician Data Restriction Program (PDRP). Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/12054.html#1. Accessed February 25, 2008.

Herscovits B. Small percentage of physicians enroll in PDRP. Pharm Exec Direct. 2006. (July 19). Available at http://www.pharmexec.com/pharmexec/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=359195&searchString=PDRP. Accessed February 25, 2008.

Lee C. Doctors, Legislators Resist Drugmakers’ Prying Eyes. Washington Post 2007 (May 22):A01.

Iskowitz M. New options arm doctors who say, ‘Don’t use my Rx data.’ Med Mark Media. 2008. January 24. Available at http://www.mmm-online.com/New-options-arm-doctors-who-say-Dont-use-my-Rx-data/article/104483/. Accessed February 24, 2008.

Tsai AC. Prescriber profiling (letter). Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(1):81. Available at http://www.annals.org/cgi/eletters/146/10/751-15848. Accessed February 25, 2008.

Musacchio RJ, Hunkler RA. More than a game of keep-away. Pharmaceutical Executive 2006 (May 1). Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/432/pdrppharexecmay06.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2008.

IMS Health Incorporated, et. al. v. Kelly Ayotte, as Attorney General of the State of New Hampshire. Case No. 06-cv-280-PB. Opinion No. 2007 DNH 061 P. Available at http://pharmedout.org/news.htm (see decision under Court Strikes Law Barring Sale of Drug Data).

American Medical Association. PDRP: the choice is yours. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/432/pdrp_brochure.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2007.

Statement of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) Maryland Senate Bill 266. February 1, 2007. Presented at hearing March 1, 2007.

Ross W. The battle of New Hampshire: a state law banning commercial use of prescription audit data is meant to protect physicians’ privacy. Med Mark Media. 2006;41(11):60–4. November. Available at http://www.mmm-online.com/The-Battle-of-New-Hampshire/article/35425/h. Accessed February 25, 2008.

IMS 2006 Annual Report. Available at http://www.imshealth.com/ims/portal/front/articleC/0,2777,6599_8650_81159942,00.html. Accessed April 24, 2008.

Crystal S, Akincigil A, Bilder S, Walkup JT. Studying prescription drug use and outcomes with Medicaid claims data: strengths, limitations, and strategies. Med Care. 2007;45(10 Suppl 2):S58–65.

Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Palumbo CM, Newcomb C, Bilker WB. Quality of Medicaid and Medicare data obtained through Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Med Care. 2007;45(12):1216–20.

Von Allmen H, Stuchlach W. Traveling through time to more accurately forecast brand performance. Product Manag Today. 2006;17(9):12–3. September.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Christopher J. McGinn for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest disclosure

Dr. Fugh-Berman is the Principal Investigator of PharmedOut.org, a project supported by a grant from the Attorney General Prescriber and Consumer Education Grant Program, created as part of a 2004 settlement between Warner-Lambert, a division of Pfizer, Inc., and the Attorneys General of 50 States and the District of Columbia, to settle allegations that Warner-Lambert conducted an unlawful marketing campaign for the drug Neurontin® (gabapentin) that violated state consumer protection laws. The views expressed in this article are her own and do not reflect the views of the funder. Dr. Fugh-Berman has served as a paid expert witness on the plaintiff’s side in litigation regarding menopausal hormone therapy and is a consultant regarding pharmaceutical marketing practices in several pending legal cases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fugh-Berman, A. Prescription Tracking and Public Health. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 1277–1280 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0630-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0630-0