Abstract

Background

Distal gastrectomy (DG) for gastric cancer can cause less morbidity than total gastrectomy (TG), but may compromise radicality. No prospective studies administered neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and few assessed quality of life (QoL).

Methods

The multicenter LOGICA-trial randomized laparoscopic versus open D2-gastrectomy for resectable gastric adenocarcinoma (cT1–4aN0–3bM0) in 10 Dutch hospitals. This secondary LOGICA-analysis compared surgical and oncological outcomes after DG versus TG. DG was performed for non-proximal tumors if R0-resection was deemed achievable, TG for other tumors. Postoperative complications, mortality, hospitalization, radicality, nodal yield, 1-year survival, and EORTC-QoL-questionnaires were analyzed using Χ2-/Fisher’s exact tests and regression analyses.

Results

Between 2015 and 2018, 211 patients underwent DG (n = 122) or TG (n = 89), and 75% of patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. DG-patients were older, had more comorbidities, less diffuse type tumors, and lower cT-stage than TG-patients (p < 0.05). DG-patients experienced fewer overall complications (34% versus 57%; p < 0.001), also after correcting for baseline differences, lower anastomotic leakage (3% versus 19%), pneumonia (4% versus 22%), atrial fibrillation (3% versus 14%), and Clavien-Dindo grading compared to TG-patients (p < 0.05), and demonstrated shorter median hospital stay (6 versus 8 days; p < 0.001). QoL was better after DG (statistically significant and clinically relevant) in most 1-year postoperative time points. DG-patients showed 98% R0-resections, and similar 30-/90-day mortality, nodal yield (28 versus 30 nodes; p = 0.490), and 1-year survival after correcting for baseline differences (p = 0.084) compared to TG-patients.

Conclusions

If oncologically feasible, DG should be preferred over TG due to less complications, faster postoperative recovery, and better QoL while achieving equivalent oncological effectiveness.

Mini-abstract

Distal D2-gastrectomy for gastric cancer resulted in less complications, shorter hospitalization, quicker recovery and better quality of life compared to total D2-gastrectomy, whereas radicality, nodal yield and survival were similar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.[1] Standard curative treatment consists of D2-gastrectomy combined with perioperative FLOT-chemotherapy in most countries, resulting in approximately 36–45% 5-year survival.[2,3,4,5] When determining the optimal surgical strategy for gastric cancer patients, accurate patient selection is crucial to safeguard oncological effectiveness. Gastric cancer limited to the distal or middle stomach is treated with distal (D2-)gastrectomy (DG), whereas total (D2-)gastrectomy (TG) is often required for gastric cancer located in the corpus, fundus, gastric cardia, or diffusely located, and for advanced disease stages or diffuse type tumors.[6]

Although both DG and TG are safe to perform, previous studies exposed several differences and concerns regarding their associated surgical and oncological outcomes.[7,8,9,10,11] DG may be associated with less morbidity, lower mortality, and better quality of life (QoL) compared to TG.[7,8,9,10] Furthermore, DG could be a sound alternative for TG for older patients with substantial comorbidities and reduced performance status. On the other hand, although overall survival may be comparable if stratified for disease stage, performing DG could compromise the proximal resection margin, especially for diffuse type tumors, and the remnant stomach is at risk for developing a new primary or secondary gastric malignancy.[7,11]

However, no prospective studies compared outcomes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and few assessed lymph node retrieval or quality of life, of which none in Western populations. Furthermore, there is heterogeneity among studies, most studies were retrospective and did not address the surgeon’s experience, and not all studies reported follow-up. Moreover, mainly Eastern populations were investigated, who differ from Western patients in disease stage, age, comorbidities, and BMI. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the role of DG and TG for Western gastric cancer patients, in particular after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, by comparing surgical and oncological outcomes including survival and quality of life after distal versus total D2-gastrectomy in the multicenter LOGICA-cohort.

Methods

Study Design

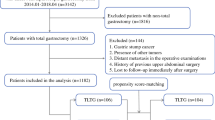

This study is a secondary analysis in the prospective, multicenter LOGICA-trial to compare surgical and oncological outcomes including QoL after DG versus TG for resectable gastric adenocarcinoma (cT1–4aN0–3bM0) in 10 Dutch hospitals. The randomized controlled LOGICA-trial (NCT02248519) compared laparoscopic versus open D2-gastrectomy and showed no significant differences in surgical nor oncological outcomes including QoL. The study protocol and results were published previously.[12,13] The LOGICA-trial was approved by institutional review boards at each participating center, and written consent was obtained for all patients.

Patient Selection and Randomization

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were listed in the LOGICA protocol.[12] In the LOGICA-trial, patients were randomly assigned to laparoscopic or open gastrectomy with a 1:1-ratio, and in the randomization procedure was stratified for extent of resection (DG or TG) and hospital of surgical treatment. In the current secondary analysis, all LOGICA-patients who underwent DG or TG with en-bloc D2-lymphadenectomy were included. Hence, patients without surgical resection, other surgery than DG/TG, and without D2-lymphadenectomy were excluded.

Staging and Treatment

Regional multidisciplinary tumor boards determined the staging and individual treatment strategy according to Dutch national guidelines, which is elaborated in the LOGICA-protocol.[4,12] Perioperative chemotherapy was recommended to all patients with advanced gastric cancer (cT3–4 and/or cN +) who were medically and physically fit to undergo this.

Consecutively, DG was performed for distal (pylorus, antrum) and middle (distal corpus) gastric cancer, whereas tumors located in the gastric cardia (Siewert type II/III according to TNM-8), fundus, upper corpus, or entire stomach were resected by TG.[14] The surgical procedures including gastrectomy, D2-lymphadenectomy according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA), complete omentectomy, and Roux-en-Y-reconstruction are described in the LOGICA study protocol.[12,15] Postoperative treatment protocols were described previously and based on enhanced recovery after surgery.[12] Postoperative complications were defined according to the Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group (ECCG) and graded following the Clavien-Dindo classification.[16,17] The histopathological resection specimen was evaluated according to the Dutch national guidelines and JGCA-classification.[4,15]

Surgeon Experience and Quality Control

Prior to the trial start, all surgeons completed the European Society for Surgical Oncology (ESSO) Training Program on Minimally Invasive Gastrectomy and at least two laparoscopic gastrectomies per surgeon were centrally reviewed by study proctors (RvH and JR).[18] Furthermore, each center performed ≥ 20 gastrectomies annually and was experienced in open gastrectomy and proficient in laparoscopic gastrectomy (≥ 20 laparoscopic cases per surgeon) for both DG and TG.

The LOGICA-trial included a mandatory surgical quality control, which comprised central assessment of intraoperatively taken photographs from the performed D2-lymphadenectomy, for which feedback was prospectively provided to participating surgeons on weekly basis.[13] Additionally, the LOGICA-protocol mandated that lymph node station nos. 1–7 were clearly marked at the resection specimen at the back-table in the operating room and station nos. 8, 9, 11p/11d, and 12a were collected in separate pathology containers.

Outcome Measures

The main outcome was overall postoperative complication rate after DG versus TG. In addition, both groups were compared regarding individual complications (i.e., anastomotic leakage, pneumonia, atrial fibrillation, ileus, abscess, pancreatic injury, chyle leakage, wound infection), mortality, oncological outcomes (e.g., radicality, marginal distances, lymph node yield, 1-year survival), intraoperative details (i.e., blood loss, operating time, conversion, additional organ resections), postoperative recovery (e.g., hospitalization, time to flatus and first oral intake, readmissions), and 1-year quality of life using EORTC QLQ-C30- and STO-22-questionnaires at baseline and after 6 weeks, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.[19,20,21] Furthermore, a cognitive workload questionnaire (The Subjective Mental Effort Questionnaire; SMEQ) was completed by surgeons immediately after surgery.[22]

Statistical Analysis

Outcomes were compared using the (independent sample) unpaired T-test or Mann–Whitney U-test depending on the data distribution. Categorical values were compared using Fisher’s exact (if ≥ 25% of values numbered ≤ 5) or Χ2-tests. Kaplan Meier curves were plotted for survival and compared with the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was utilized to analyze overall survival, and Poisson regression with robust error variances was applied to compare overall complications after DG versus TG, and in both analyses was adjusted for the baseline differences in age, comorbidities, disease stage, and histological subtype.[23,24] The time period for survival was time in days from inclusion to death due to any reason. QoL was compared using linear mixed-effects regression, adjusting for baseline-QoL and stratifying for hospital of surgical treatment. Differences in QoL-scores were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and categorized in trivial, small, medium, or large differences for each individual QoL-subscale separately according to previous QoL-guidelines to assess their clinical relevance.[25,26] A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests, which were performed by IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA).

Results

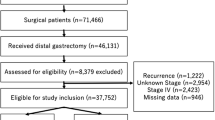

Between 2015 and 2018, 211 of the 227 LOGICA-patients (93%) were included (Fig. 1) and underwent DG (n = 122) or TG (n = 89). Patients were excluded if they did not undergo surgical resection of the tumor (n = 14), or underwent esophagogastric resection (n = 1) or D1 + /D1-lymphadenectomy (n = 1).

The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients undergoing DG were older (69 versus 66 years; p = 0.041) and had more comorbidities (88% versus 74%; p = 0.019), more distal tumors (77% versus 30%; p < 0.001), less diffuse type tumors (31% versus 51%; p = 0.005), and lower clinical T-stage (p = 0.001) compared to patients undergoing TG.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 157 of the 211 patients (74%) in similar proportions for DG- versus TG-patients (71% versus 79%; p = 0.240), and consisted of the MAGIC-regimen or an equivalent regimen (n = 120/157; 76%), FLOT-regimen (n = 28/157; 18%), or other regimens (n = 9/157; 6%).

Intraoperative Data

Intraoperative details are listed in Table 2. All patients (n = 211; 100%) underwent D2-lymphadenectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Jejunal pouch reconstruction was performed in 18% of TG-patients. Jejunal feeding tube placement (7% versus 30%; p < 0.001) was less often performed after DG than TG. The proportion laparoscopic resections was comparable regarding DG versus TG (48% versus 54%; p = 0.437). Unplanned splenectomy was performed less frequently during DG versus TG (0% versus 4%; p = 0.030), whereas pancreatectomy rate was not different (0% versus 2%; p = 0.177). DG led to significantly shorter operating time (mean 196 versus 218 min; p = 0.007) and less blood loss (median 200 versus 300 mL; p = 0.001) compared to TG, whereas intraoperative complications were similar (p = 0.230). The surgeon mental effort between DG and TG differed but did not reach statistical significance (53.9 versus 60.1; p = 0.087).

Postoperative Data

Postoperative complications and recovery are shown in Table 3. Overall postoperative complication rate was significantly lower after DG versus TG (34% versus 57%; p = 0.001). Also after correcting for confounders and for the baseline differences in age, comorbidities, histological subtype, and cT-stage using multivariable Poisson regression with robust error variances (Supplementary Table 1), there were significantly fewer overall postoperative complications after DG compared to TG (p < 0.001).

In addition, anastomotic leakage (3% versus 19%; p < 0.001), pneumonia (7% versus 23%; p = 0.003), atrial fibrillation (4% versus 14%; p = 0.020), and the severity of overall complications illustrated in Clavien-Dindo grading (p = 0.006) and anastomotic leakage illustrated in ECCG-grading (p < 0.001) were significantly lower in favor of DG compared to TG.[16,17] Other complications and 30-/90-day mortality rates were similar for both groups (p > 0.05).

The median number of days were significantly different in favor of DG-patients compared to TG-patients regarding time to first oral intake (90% versus 70% within 1 day; p = 0.005), time to first defecation (73% versus 55% within 4 days; p = 0.003), meeting discharge criteria (6 versus 8 days; p < 0.001), hospital stay (6 versus 8 days; p < 0.001), and intensive care unit (ICU) stay (88% versus 73% no ICU-admission at all; p = 0.006). Readmission rates within 30 days after discharge did not differ for both groups (12% versus 7%; p = 0.272).

Regarding surgical approach (laparoscopic versus open), there were no significant differences in postoperative complications, hospitalization, or postoperative recovery, which was further elucidated in detail in the previously published LOGICA-trial main results.[13]

Oncological Outcomes

Histopathological results are listed in Table 4. Patients selected for DG had 98% R0-resection rate (n = 120/122). After TG, R0-resection rate (91%; n = 81/89) was lower (p = 0.019), but the TG-group had larger tumor diameter (55 versus 35 mm; p = 0.023), higher clinical T-stages (p = 0.001), and more diffuse type tumors (51% versus 31%; p = 0.005). Hence, after correcting for these variables and confounders using multivariable logistic regression (Supplementary Table 2), the resection margin status between both groups was similar (p = 0.264).

Positive resection margins after DG (n = 2) were both diffuse type (distal) tumors extending into the proximal margin. After TG, the positive margins (n = 8) were either proximal (n = 4) or both proximal and distal (n = 4), of whom 7 patients (88%) had diffuse type tumors, and these 8 tumors were located proximal (n = 1), middle (n = 3), and distal (n = 4). Proximal margin distances were larger after DG (50 versus 28 mm; p = 0.002) as DG-patients had more distal tumors (77% versus 30%), while TG-patients had more proximal tumors (0% versus 25%) resulting in larger distances to distal margins (25 versus 40 mm; p = 0.030).

When evaluating resection margin status in subgroups (Supplementary Table 3), R1-resections occurred more frequently for diffuse versus intestinal type tumors for both DG-patients (95% versus 100% R0) and TG-patients (84% versus 98% R0). Regarding cT3-4- versus cT1-2-stage, more R1-resections were found for TG-patients (89% versus 100% R0), but not for DG-patients (98% versus 98% R0). After neoadjuvant chemotherapy (yes versus no), the resection margin status was similar after both DG (yes; 98% versus no; 100%) and TG (yes; 91% versus no; 90%). In multivariable regression analyses (Supplementary Table 2), diffuse type tumors were independently associated with positive resection margins (OR 10.04; p = 0.035), whereas cT-stage (OR 2.76; p = 0.371) and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (OR 1.03; p = 0.973) were not.

Median lymph node yield (28 versus 30 nodes; p = 0.490), (y)pT-stage (p = 0.089), and Mandard tumor regression grading (p = 0.400) were similar in both groups (p > 0.05).

Overall survival analyses are displayed in Table 5. Univariate analysis and Kaplan Meier curves (Supplementary Fig. 1) showed better overall survival for the DG- versus TG-group (p < 0.05), but did not incorporate differences in baseline. Hence, after adjusting for the baseline differences in age, comorbidities, tumor location, histological subtype, and cT-stage in multivariable analyses, overall survival for patients undergoing DG versus TG was not significantly different (p = 0.084). The only independent predictor for overall survival was administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (HR 0.41 [95% CI 0.20–0.87]; p = 0.020).

Quality of Life

[]The QoL differences reported by patients undergoing DG versus TG postoperatively at 6 weeks and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months are shown in Table 6. After correcting for baseline QoL and hospital of surgical treatment in the linear mixed-effects regression, QoL was significantly better after DG for global health, in 6 out of 7 functional scales, and for 13 of the 17 symptom scales during at least one or all time points [95% CI did not include 0 points difference]. When assessing clinical relevance, most significantly different QoL-values ranged ≥ 10 points favoring DG compared to TG with regard to global health, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, pain, reflux, insomnia, appetite loss, eating restrictions, diarrhea, role functioning, body image, anxiety, dry mouth, and taste. At all time points, the significant QoL-differences were also clinically relevant, categorized in either medium (41%) or small (59%) differences, without any trivial (0%) differences.[25,26]

[Edit]

The raw 1-year QoL-data are displayed in Supplementary Table 4 and 5. After DG, all functional and symptom scales seemed to restore to the preoperative baseline at 3 months after surgery. After TG, most items recovered generally in 6 months, and no full recovery within 12 months was found for pain, dysphagia, reflux, eating restrictions, diarrhea, and body image. For DG, global health-related QoL; role, emotional, and social functioning; pain; dysphagia; and anxiety showed median 6–17 points better QoL-values at 6–12 months than preoperatively. Such improvements were not found after TG.

The proportion of patients with preoperative weight loss was similar after DG and TG (56% versus 58%; p = 0.797). At 1 year postoperatively, 64% of patients (n = 73/115) had ≥ 2 kg weight loss, which occurred less frequently after distal than total gastrectomy (52% versus 83%; p = 0.003), as shown in Supplementary Table 6. Compared to preoperative weight, median weight differences at 1 year were significant (p < 0.001), showing − 4 kg after DG [IQR + 1 to − 8 kg] and − 10 kg after TG [− 5 to − 15 kg].

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the role of DG for Western gastric cancer patients by comparing surgical and oncological outcomes including quality of life after DG versus TG, in particular in a population where the vast majority of patients was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients selected to undergo DG experienced significantly fewer and less severe postoperative complications, also after correcting for baseline differences. Furthermore, DG-patients had better intraoperative surgical outcomes, shorter hospital and ICU stay, and quicker postoperative recovery compared to TG-patients. Moreover, the reported quality of life after DG was significantly better in most functional and symptom scales at one or all time points, and the significant differences were also clinically relevant based on previous guidelines.[25,26] Additionally, radicality and overall survival corrected for baseline differences were comparable between both groups, and postoperative mortality and lymph node yield were similar. These results confirm the surgical safety and oncological effectiveness of DG for Western gastric cancer patients if carefully selected based on tumor and patient characteristics, also after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and for advanced disease stage.

In the present study, both DG and TG were oncologically effective and oncological outcomes were concordant with current standards.[2,3,4,27,28,29] Gastrectomy for gastric cancer is primarily aimed at achieving R0-resection, which has been correlated with prolonged survival.[30,31] In the current study, TG was often required for proximal, advanced, diffuse type gastric cancer with larger tumor size to achieve radical resections. Two previous meta-analyses did not compare resection margin status between DG and TG.[7,32] Although DG could theoretically compromise the proximal resection margin, our cohort presented a very good 98% R0-resection rate after DG. Additionally, this conclusion was robust to subgroup-analyses of only DG-patients for advanced disease stage (98%), diffuse type tumors (95%), and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (98%), which is in line with a previous study.[33] Furthermore, lymph node yield and overall survival stratified for disease stage and corrected for the baseline differences were comparable in both groups, as was also demonstrated in previous studies.[7,32] Therefore, our results strongly support performing DG for both early and advanced gastric cancer located in the middle and/or distal stomach, also for the diffuse histological subtype and irrespective of neoadjuvant treatment, but on the essential condition that the proximal resection margin is secured. To this end, intraoperative frozen sections show low rates of false-negative outcomes (1–2.5%) and are highly recommended, especially for diffuse type and signet ring cell carcinomas which independently predicted positive resection margins in our cohort and previous studies.[34,35,36,37]

Importantly, our results demonstrate that DG resulted in fewer and less severe postoperative complications (overall, anastomotic leakage, pneumonia, and atrial fibrillation), less blood loss and splenectomy, shorter operating time and hospital and ICU stay, quicker postoperative recovery, and better quality of life compared to TG. This is in line with a previous nationwide evaluation.[29] Additionally, a meta-analysis of 3554 patients containing mostly retrospective studies and few clinical trials, all without neoadjuvant chemotherapy, reported similar results favoring DG and showed that TG-patients suffer from higher complication and mortality rates, longer operating time, and more intraoperative blood loss.[7] Hence, DG results in optimal safety of surgery due to lower perioperative morbidity, shorter hospitalization, faster postoperative recovery, and better patient-reported outcomes, both with and without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This strongly supports performing DG after careful patient selection.

Patients in the current study experienced significantly better quality of life after DG versus TG regarding most functional and symptom scales at one or all time points in the 1-year follow-up (predominantly ≥ 10 points difference), possibly as a consequence of functional preservation of part of the stomach. Importantly, all significant differences were also clinically relevant and categorized in medium (41%) or small differences (59%) based on previous guidelines, without any trivial (0%) differences.[25,26] The current Western cohort presents unique and comprehensive prospective quality of life data with substantial improvements favoring DG. Interestingly, QoL-items after DG restored to the preoperative baseline faster than after TG (± 3 versus 6–12 months). Moreover, after DG, 7 items even reached better QoL-values at 6–12 months after surgery than preoperatively, whereas after TG several symptoms (pain, reflux, eating restrictions, diarrhea) did not fully recover within 12 months. The reported quality of life scores were comparable in value to a previous nationwide evaluation, suggesting that our results are representative.[38] Three previous single-center Asian studies without neoadjuvant chemotherapy assessed quality of life and presented similar conclusions.[8,9,10] Accordingly, although TG results in acceptable quality of life, DG leads to better quality of life, also after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

To complement the abovementioned, several recommendations for surgical decision making can be stated. The surgical strategy (DG or TG) should primarily be based upon achieving a radical D2-gastrectomy, and may secondarily be adjusted to ensure safety of surgery. It should be noted that there is not always a “choice” for surgeons between performing DG or TG; for instance, proximal tumors are not eligible for distal gastrectomy. In the current study, the differences in baseline characteristics reflect this surgical selection process. Notably, the R0-resection rates after DG and TG (98% versus 91%) should be interpreted within the context of these baseline differences, since the TG-group contained proximal tumors and had larger tumor diameters (p = 0.023), higher cT-stages (p = 0.001), and more diffuse type tumors (p = 0.005), which predict positive resection margins.[30,31] In addition, patients selected to undergo DG were older and had more comorbidities compared to TG-patients. Since patients with older age, more comorbidities, poor performance status, and deteriorated body composition during neoadjuvant chemotherapy have been related to poorer surgical perioperative outcomes, such characteristics should also be taken into account when selecting patients for DG or TG.[39,40,41] Furthermore, although infrequently, gastric cancer of the remnant stomach after DG can occur at long-term, which should not be neglected in the surgical decision making.[11] Hence, incorporating both tumor and patient characteristics when balancing radicality, surgical risk and morbidity in order to determine the extent of resection (DG or TG) is crucial.

The costs of surgery are not always incorporated when clinically considering distal or total gastrectomy; however, this is highly relevant for hospital management. In the LOGICA-trial, we had previously assessed the cost-effectiveness of D2-gastrectomy in detail: the mean total costs of D2-gastrectomy including costs associated with surgery (e.g., hospitalization, diagnostic modalities, complications, re-interventions, medication, emergency visits, rehabilitation and nursing homes, and productivity loss) noted €21,939 per distal and €31,583 per total D2-gastrectomy.[42] This substantial cost-difference in favor of DG is mainly due to the lower complication rate, shorter hospitalization, and shorter operating time after DG versus TG, and may play a role in surgical decision making.

Since patients selected for DG differ in baseline from TG-patients by definition as described, this limits statistical comparison to some extent. However, the baseline differences are inherent to the indication per surgical procedure (DG/TG), and our findings consistently support DG in alignment with previously mentioned studies. Furthermore, several details of the Roux-en-Y reconstruction, including length of Roux-limbs and antecolic/retrocolic position and jejunal pouch formation and size, were not standardized in the LOGICA-trial, which could have resulted in (minor) differences in QoL-results between DG and TG.[43,44] Strengths of this study are the LOGICA-randomization procedure that stratified for extent of resection (DG/TG) and hospital of surgical treatment, therefore minimizing selection bias, hospital reporting bias for postoperative complications, and differences in surgical outcomes due to hospital variation. In addition, the current secondary LOGICA-trial analysis is the first to assess surgical and oncological outcomes for Western gastric cancer patients in a prospective multicenter cohort incorporating neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the first to report on quality of life after DG versus TG in a Western population. The reported outcomes may be considered high quality and representative for the Dutch population as 10 high-volume upper-GI centers participated.

In conclusion, Western gastric cancer patients selected for DG experienced fewer and less severe complications (overall, anastomotic leakage, pneumonia, atrial fibrillation), demonstrated quicker postoperative recovery, and reported substantial better quality of life, also after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, while oncological effectiveness after DG was safeguarded. Therefore, in selected patients where DG is oncologically feasible, DG should be preferred over TG. Alternatively, TG is safe and effective if adequate oncological control cannot be achieved with DG. To determine the optimal surgical strategy for each gastric cancer patient, it is crucial to individually balance radicality, surgical morbidity and quality of life.

Data Availability

Prof. dr. R. van Hillegersberf had full access to all trial data. The data are not publicly available for privacy reasons, and may be provided upon reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, Goetze TO, Meiler J, Kasper S, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a ra. Lancet 2019;393:1948–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1.

Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ, Smith DB, Langley RE, Verma M, Weeden S, Chua YJ MTP. Perioperative Chemotherapy versus Surgery Alone for Resectable Gastroesophageal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11–20.

Vereniging van Integrale Kankercentra. Dutch national guidelines. Diagnostics, treatment and follow-up of gastric cancer. Version 2.2. last updated: 2017–03–01. 2017:1-162.

Gertsen EC, Brenkman HJF, Haverkamp L, Read M, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. Worldwide Practice in Gastric Cancer Surgery: A 6-Year Update. Dig Surg 2021:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000515768.

Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965;64:31–49.

Li Z, Bai B, Xie F, Zhao Q. Distal versus total gastrectomy for middle and lower-third gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2018;53:163–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.03.047.

Huang CC, Lien HH, Wang PC, Yang JC, Cheng CY, Huang CS. Quality of life in disease-free gastric adenocarcinoma survivors: Impacts of clinical stages and reconstructive surgical procedures. Dig Surg 2007;24:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1159/000100920.

Park S, Chung HY, Lee SS, Kwon O, Yu W. Serial comparisons of quality of life after distal subtotal or total gastrectomy: What are the rational approaches for quality of life management? J Gastric Cancer 2014;14:32–8. https://doi.org/10.5230/jgc.2014.14.1.32.

Lee SS, Chung HY, Kwon OK, Yu W. Long-term quality of life after distal subtotal and total gastrectomy: symptom- and behavior-oriented consequences. Ann Surg 2016;263:738–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001481.

Hanyu T, Wakai A, Ishikawa T, Ichikawa H, Kameyama H, Wakai T. Carcinoma in the Remnant Stomach During Long-Term Follow-up After Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: Analysis of Cumulative Incidence and Associated Risk Factors. World J Surg 2018;42:782–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4227-9.

Haverkamp L, Brenkman HJF, Seesing MFJ, Gisbertz SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Luyer MDP, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer, a multicenter prospectively randomized controlled trial (LOGICA-trial). BMC Cancer 2015;15:556.

Van der Veen A, Brenkman HJF, Seesing MFJ, Haverkamp L, Luyer MDP, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, et al. Laparoscopic Versus Open Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer (LOGICA): A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:978–89. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.20.01540.

American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition. Ann Oncol 2018;14:345. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdg077.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer 2020;24:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y.

Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, Chang AC, Darling GE, Benoit D’Journo X, et al. International Consensus on Standardization of Data Collection for Complications Associated With Esophagectomy. Ann Surg 2015;262:286–94.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13.

European Society for Surgical Oncology (ESSO). European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO) hands-on course on minimally invasive gastrectomy and esophagectomy 2014. https://www.essoweb.org/courses/esso-hands-course-minimally-invasive-esophagectomy-and-gastrectomy-2022/. Accessed 20 Nov 2022.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–78.

Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, Vickery C, Arraras J, Sezer O, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2260–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2004.05.023.

Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. Eur Organ Res Treat Cancer 2001;30:1–67.

Zijlstra F. Efficiency in work behaviour: a design approach for modern tools. Doctoral thesis, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands 1993. Available at: https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3Ad97a028b-c3dc-4930-b2ab-a7877993a17f.

Zou G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh090.

Knol MJ, Le Cessie S, Algra A, Vandenbroucke JP, Groenwold RHH. Overestimation of risk ratios by odds ratios in trials and cohort studies: Alternatives to logistic regression. Cmaj 2012;184:895–9. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101715.

Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, St-James MM, Fayers PM, Brown JM. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:89–96. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0107.

Osoba BD, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the Significance of Changes in Health-Related Quality-of-Life Scores. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:139–44.

van der Werf LR, Busweiler LAD, van Sandick JW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, the Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit (DUCA) Group. Reporting National Outcomes After Esophagectomy and Gastrectomy According to the Esophageal Complications Consensus Group (ECCG). Ann Surg 2019;271:1095–101.

Busweiler LAD, Jeremiasen M, Wijnhoven BPL, Lindblad M, Lundell L, van de Velde CJH, et al. International benchmarking in oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery. BJS Open 2019;3:62–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50107.

Gertsen EC, Brenkman HJF, Seesing MFJ, Goense L, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R, et al. Introduction of minimally invasive surgery for distal and total gastrectomy: a population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:403–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.08.015.

Wang SY, Yeh CN, Lee HL, Liu YY, Chao TC, Hwang TL, et al. Clinical impact of positive surgical margin status on gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:2738–43. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0616-0.

Kim SY, Hwang YS, Sohn TS, Oh SJ, Choi MG, Noh JH, et al. The predictors and clinical impact of positive resection margins on frozen section in gastric cancer surgery. J Gastric Cancer 2012;12:113–9. https://doi.org/10.5230/jgc.2012.12.2.113.

Qi J, Zhang P, Wang Y, Chen H, Li Y. Does total gastrectomy provide better outcomes than distal subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165179.

Lee HJ, Hyung WJ, Yang HK, Han SU, Park YK, An JY, et al. Short-term outcomes of a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy to open distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer (KLASS-02-RCT). Ann Surg 2019;270:983–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003217.

Aurello P, Magistri P, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Novi L, Antolino L, et al. Surgical management of microscopic positive resection margin after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A systematic review of gastric R1 management. Anticancer Res 2014;34:6283–8.

Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, Jean-Pierre T, Mariette C. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg 2009;250:878–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b21c7b.

Squires MH, Kooby DA, Pawlik TM, Weber SM, Poultsides G, Schmidt C, et al. Utility of the Proximal Margin Frozen Section for Resection of Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A 7-Institution Study of the US Gastric Cancer Collaborative. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:4202–10. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3834-z.

McAuliffe JC, Tang LH, Kamrani K, Olino K, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF, et al. Prevalence of False-Negative Results of Intraoperative Consultation on Surgical Margins during Resection of Gastric and Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg 2019;154:126–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3863.

Brenkman HJF, Tegels JJW, Ruurda JP, Luyer MDP, Kouwenhoven EA, Draaisma WA, et al. Factors influencing health-related quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer. Gastric Cancer 2018;21:524–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0771-0.

Van Gestel YRBM, Lemmens VEPP, De Hingh IHJT, Steevens J, Rutten HJT, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, et al. Influence of comorbidity and age on 1-, 2-, and 3-month postoperative mortality rates in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:371–80. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2663-1.

Yan Y, Yang A, Lu L, Zhao Z, Li C, Li W, et al. Impact of Neoadjuvant Therapy on Minimally Invasive Surgical Outcomes in Advanced Gastric Cancer: An International Propensity Score-Matched Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:1428–36. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09070-9.

Zhang Y, Li Z, Jiang L, Xue Z, Ma Z, Kang W, et al. Impact of body composition on clinical outcomes in people with gastric cancer undergoing radical gastrectomy after neoadjuvant treatment. Nutrition 2021;85:111135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2020.111135.

Van der Veen A, Van der Meulen M, Seesing M, Brenkman H, Haverkamp L, Luyer M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic vs open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an economic evaluation alongside a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2023;158(2):120–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.6337.

Brenkman HJF, Correa-Cote J, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. A Step-Wise Approach to Total Laparoscopic Gastrectomy with Jejunal Pouch Reconstruction: How and Why We Do It. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:1908–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-016-3235-7.

Gertler R, Rosenberg R, Feith M, Schuster T, Friess H. Pouch vs. no pouch following total gastrectomy: meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2838–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all LOGICA-patients and everyone from the participating hospitals who contributed in including patients, completing the data collection or locally coordinating the LOGICA-trial. For providing an unrestricted educational grant to enable proctoring of laparoscopic gastrectomy in participating centers before starting the LOGICA-trial, the authors thank Johnson & Johnson.

COLLABORATORS (LOGICA Study Group): Hylke JF Brenkman1, Maarten F.J. Seesing1, Misha DP Luyer2, Jeroen EH Ponten2, Juul JW Tegels3, Karel WE Hulsewe3, Bas PL Wijnhoven4, Sjoerd M Lagarde4, Wobbe O de Steur5, Henk H Hartgrink5, Ewout A Kouwenhoven6, Marc J van Det6, Eelco Wassenaar7, P. van Duijvendijk7, Werner A Draaisma8, Ivo AMJ Broeders8, Susanne S Gisbertz9, Donald L van der Peet10, Hanneke WM van Laarhoven10*.

1*UMC Utrecht, Department of Pathology, Utrecht, The Netherlands. 2Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, Department of Surgery, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. 3Zuyderland Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Sittard, The Netherlands. 4Erasmus UMC, Department of Surgery, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 5Leiden UMC, Department of Surgery, Leiden, The Netherlands. 6ZGT Almelo, Department of Surgery, Almelo, The Netherlands. 7Gelre Hospitals Apeldoorn, Department of Surgery, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands. 8Meander Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Amersfoort, The Netherlands. 9Amsterdam UMC, Location VUmc, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 10Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 10*Amsterdam UMC, Location AMC, Department of Medical Oncology, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Funding

The LOGICA-trial (NCT02248519) was funded by ZonMw (The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development), project number 837002502.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Richard van Hillegersberg: consulting or advisory role: intuitive surgical, Medtronic. Jelle Ruurda: consulting or advisory role: intuitive surgical. Lodewijk Brosens: advisory role: Bristol Myers Squibb. Grard Nieuwenhuijzen: consulting or advisory role: Medtronic. The other authors have no disclosures. All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Jongh, C., van der Veen, A., Brosens, L.A.A. et al. Distal Versus Total D2-Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: a Secondary Analysis of Surgical and Oncological Outcomes Including Quality of Life in the Multicenter Randomized LOGICA-Trial. J Gastrointest Surg 27, 1812–1824 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-023-05683-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-023-05683-z