Abstract

Background/Purpose

Medicare’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program disproportionately penalizes safety-net hospitals (SNH) caring for vulnerable populations. This study assessed the association of insurance type with 30-day emergency department visits/observation stays (EDOS), readmissions, and cumulative costs in colorectal surgery patients.

Methods

Retrospective inpatient cohort study using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (2013–2019) with cost data in a SNH. The odds of EDOS and readmissions and cumulative variable (index hospitalization and all 30-day EDOS and readmissions) costs were modeled adjusting for frailty, case status, presence of a stoma, and open versus laparoscopic surgery.

Results

The cohort had 245 private, 195 Medicare, and 590 Medicaid/uninsured cases, with a mean age 55.0 years (SD = 13.3) and 52.9% of the cases were performed on male patients. Most cases were open surgeries (58.7%). Complication rates were 41.8%, EDOS 12.0%, and readmissions 20.1%. Medicaid/uninsured had increased odds of urgent/emergent surgeries (aOR = 2.15, CI = 1.56–2.98, p < 0.001) and complications (aOR = 1.43, CI = 1.02–2.03, p = 0.042) versus private patients. Medicaid/uninsured versus private patients had higher EDOS (16.6% versus 4.1%) and readmissions (22.9% versus 14.3%) rates and higher odds of EDOS (aOR = 4.81, CI = 2.57–10.06, p < 0.001), and readmissions (aOR = 1.62, CI = 1.07–2.50, p = 0.025), while Medicare patients had similar odds versus private. Cumulative variable cost %change was increased for Medicare and Medicaid/uninsured, but Medicaid/uninsured was similar to private after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases.

Conclusions

Increased urgent/emergent cases in Medicaid/uninsured populations drive increased complications odds and higher costs compared to private patients, suggesting lack of access to outpatient care. SNH care for higher cost populations, receive lower reimbursements, and are penalized by value-based programs. Increasing healthcare access for Medicaid/uninsured patients could reduce urgent/emergent surgeries, resulting in fewer complications, EDOS/readmissions, and costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal surgeries (CRS) are among the most commonly performed procedures with high rates of complications,1 emergency department visits/observation stays (EDOS),2 and readmissions.2 CRS are resource intensive, and readmissions can more than double median hospital costs.3,4 However, readmissions may not reflect quality of care as a quality metric.3 For example, safety-net hospitals (SNH) have higher rates of complications and readmissions,5 but care for higher proportions of vulnerable patients who have increased rates of poor outcomes.5 Low socioeconomic status (SES) populations are associated with greater risk of morbidity,6 mortality,5 and poor health status.6 Current risk adjustment models do not include frailty7,8,9 and social risk factors10,11,12 which significantly impact patient outcomes.11,12,13,14,15 With the higher costs of care for low-SES populations, in addition to lower reimbursements, SNH are further penalized by current value-based programs.16,17

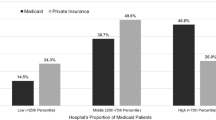

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is a Medicare value-based program used as a quality measure and to decrease healthcare spending. HRRP reduces payments to hospitals with higher 30-day readmissions than predicted by risk-adjustment models.18 The payment reductions have disproportionately penalized SNHs.19,20,21,22,23,24 Stratifying hospitals into five groups based upon percent of dual enrollment Medicare–Medicaid patients reduced but did not eliminate SNH penalties.25 The typical SNH still receives a 0.28% reduction across all Medicare payments and 91.6% of low-socioeconomic status/high-burden hospital experience penalties.25 Readmission penalties in 2019 impacted 75% of all hospitals.25

Our primary clinical objective was to assess the association of insurance type with 30-day EDOS and readmissions in an academic SNH serving a diverse population. Our cost objectives were to assess the association of insurance type with (1) the variable costs of the index hospitalization for patients without and with EDOS or readmissions, (2) the costs of the initial EDOS or readmission, (3) the cumulative costs of the index hospitalization and all 30-day EDOS and readmissions, and (4) return costs (sum of all 30-day EDOS and readmissions).

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data

This study used a retrospective cohort of inpatients undergoing CRS using data in the 2013–2019 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) at an academic medical center and SNH following STROBE Reporting Guidelines. NSQIP started at our hospital in April 2013 with random selection of colorectal surgeries. In mid-2016 all eligible colorectal surgeries were included in NSQIP. NSQIP registry provides standardized definitions of preoperative risk factors and complications.26,27,28 Patient self-reported race and ethnicity were derived from NSQIP variables and electronic health records (EHR). Dates of death were obtained from NSQIP and supplemented by EHR and the Social Security Death Master File.29 The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Texas Health San Antonio approved this study.

Estimating Patient Frailty/Premorbid Conditions

Frailty was measured using the recalibrated Risk Analysis Index (RAI)7 using preoperative variables from NSQIP.30,31 RAI has been validated using NSQIP and Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program datasets.7,31,32 RAI exhibits collinearity33 with the Charlson Comorbidity Index. RAI is used as a single-variable estimate of patient-level variability that overcomes barriers to model fit encountered by less parsimonious models and has been used to risk adjust for medical comorbid conditions in multiple studies.30,34,35,36,37,38 RAI scores were grouped into robust (≤ 20), normal (21–29), frail (30–39), and very frail (≥ 40), as previously described.30,34,37,38

Procedure Identification, Stoma, Case Status, and 30-Day Complications

CRS were identified and categorized as open or laparoscopic surgeries using NSQIP principal Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (Supplementary Table 1). All CPT codes used for billing during the index hospitalization were assessed; patients with any CPT code specifying operative placement of a stoma or associated with the presence of a stoma (e.g., endoscopy performed through a stoma) were classified as having stoma regardless of the principal CPT code. Chart review was performed on cases with CPT codes with optional stoma placement to determine stoma status (Supplementary Table 1).

Case status was determined from NSQIP variables with urgent cases being defined as “no” responses to elective and emergency variables.39 Any complication was defined using the 20 NSQIP variables defining postoperative complications (Supplementary Table 2).

30-Day EDOS and Readmissions

NSQIP only tracks patients for 30 days after surgery and contains 30-day readmission variables from the date of surgery. We merged NSQIP data with EHR to determine readmissions and EDOS within 30 days of discharge from the index procedure’s hospitalization, to be consistent with the HRRP definition of 30-day readmissions.

Insurance Type and Cost Data

The identified, local NSQIP data were merged with EHR and managerial accounting data to determine insurance type and cost of the index hospitalization, readmissions, and EDOS. Insurance type was categorized based upon billing data for the encounter supplemented by EHR data and defined as (1) private insurance including workers’ compensation, (2) Medicare, and (3) Medicaid/uninsured including Medicaid, dual enrollment in Medicare/Medicaid, Charity Care, self-pay, or county indigent care programs (Supplementary Table 3). Patients enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid were allocated only to the Medicaid/uninsured group. “Other” included encounters billed to the Veterans Administration, Department of Corrections, or self-pay with > 1% of charges collected and were excluded.

Our hospital used EPSi for internal cost accounting. EPSi provides an array of accounting functions including real-time costing, budgeting, productivity measurement, and decision support. We defined variable costs as costs related directly to patient care occurring during the encounter, such as supplies and salaries, and include direct variable costs that vary directly with the quantity of resources provided for patient care. Variable costs were derived using direct measurements from a bottom-up approach, rather than calculated estimates derived from charges. Fixed costs include money used on facilities such as insurance for buildings and equipment and do not vary with the number of patients served. Fixed costs represent a substantial portion of a hospital’s budget40,41 and cannot be reduced in the short term.42 We used variable costs, as fixed costs are not directly related to patient care and vary between hospitals.43 Hospital fixed costs, outpatient, and professional fees were not included as the focus of this study was on variable costs to the hospital for an inpatient surgical procedure and subsequent EDOS and readmissions.44 The natural logarithm of variable costs was used, as previously described,45 after adjusting costs to 2019 dollars using the Personal Health Care Index.46

Exclusions

Cases were excluded due to (1) perineal or sacral procedures, (2) other insurance type, and (3) missing cost data for index hospitalization or readmission/EDOS costs, including readmissions to outside hospitals.

Patient mortality resulting in no or reduced chances of subsequent EDOS and readmissions were excluded, as previously described.20 Cases were excluded due to (1) death during the index hospitalization, (2) discharge to another acute care hospital, (3) discharge against medical advice, (4) death within 30 days of discharge when discharged to Hospice or Home on Hospice, and (5) death within 30 days of discharge without a 30-day EDOS or readmission. A sensitivity analysis was performed adding groups 1–5 (34 cases) to ensure clinical outcomes were robust to cohort selection (Fig. 1).

Cohort flow diagram. National Surgery Quality Improvement Program inpatient cases from 2013 to 2019. Cases were excluded for perineal or transsacral only procedures, “other” insurance status, and missing cost data. “Other” insurance status was defined as included encounters billed to the Veterans Administration, Department of Corrections, or self-pay with > 1% of charges collected. Cases were excluded for missing cost data and for patient mortality resulting in no or reduced chances of subsequent Emergency Department Visits/Observation Stays (EDOS) and readmissions leaving a final study cohort of 1030 cases. A sensitivity analysis was performed to add 34 previously excluded cases; the cases added for the sensitivity analysis are marked with bold text

Study Outcomes

Our main clinical analyses were the association of insurance type with EDOS and readmissions. Sub-analyses assessed the association of insurance type with EDOS and readmission risk factors of urgent/emergent cases,47 open abdominal procedures,3 presence of a stoma,3,47 and postoperative complications.47

Our cost analyses included the association of insurance type with (1) index hospitalization costs for patients without and with an EDOS or readmission, (2) costs of initial EDOS and readmission, (3) cumulative costs of the index hospitalization and subsequent 30-day EDOS and readmissions, and (4) return costs (sum of all 30-day EDOS and readmissions).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data was summarized using count and percentage, with continuous data using mean and standard deviation (SD) or medians with quartiles. Chi-square tests and F-tests tested differences between groups for categorical and continuous variables, except length of stay (LOS) and variable costs for (1) the index hospitalization, (2) EDOS, (3) readmissions, (4) cumulative costs, and (5) return costs which used Kruskal–Wallis tests. Logistic regression analyses were performed for case status and complications adjusting for a combination of RAI, open versus laparoscopic procedure, case status, and insurance type. Natural logarithms normalized the skewed LOS and variable costs reducing the impact of outliers, as previously described.45,48 Percent change/relative difference was calculated using the exponential function; %change = (eEstimate coefficients − 1)*100. Analyses were performed using R 4.1.0 (2021–05-18).

Results

Population Demographics

Our cohort consisted of 1030 cases of colorectal procedures (Fig. 1). Most cases (Table 1) were performed on male (52.9%) and White patients (90.1%), with a majority identifying as Hispanic (64.6%). Cases were performed on Medicaid/uninsured insurance patients (57.3%), private (23.8%), and Medicare (18.9%). Most patients were robust (61.7%) or normal (27.1%) based on RAI scores. Only 9.2% and 1.9% of cases involved frail and very frail patients, respectively, with Medicare patients having higher frailty scores.

Clinical Analysis Outcomes

Increased Urgent/Emergent Cases in Medicare and Medicaid/Uninsured Patients with Similar Odds of Having a Stoma and Open Abdominal Procedure

Urgent/emergent surgeries were higher in Medicaid/uninsured (47.6%) and Medicare (36.4%) patients versus private (28.6%, Table 1). Medicaid/uninsured (aOR = 2.15, CI = 1.56–2.98, p < 0.001), but not Medicare patients, had higher odds of an urgent/emergent surgeries versus private (Table 2). Increased odds of having a stoma or undergoing an open abdominal procedure were associated with frail and very frail patients (Table 2 M1 and M2). Adjusting for urgent/emergent cases (Table 2 M2) increased the odds of having a stoma (aOR = 2.53, CI = 1.95–3.31, p < 0.001) and undergoing an open abdominal procedure (aOR = 2.80, CI = 2.13–3.70, p < 0.001). Medicaid/uninsured (aOR = 1.37, CI = 1.01–1.86, p = 0.043) patients demonstrated higher odds of undergoing open abdominal surgery versus private (Table 2 M1) but were similar to private after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases (Table 2 M2).

Increased Complications in Medicare and Medicaid/Uninsured Patients

Higher odds of complications (Table 3 M1) occurred with open abdominal cases (aOR = 2.64, CI = 1.96–3.57, p < 0.001) and having a stoma (aOR = 3.39, CI = 2.55–4.53, p < 0.001). Complications were higher in Medicare (47.2%), followed by Medicaid/uninsured (44.2%) compared to private (31.8%, Table 1). Medicaid/uninsured (aOR = 1.43, CI = 1.02–2.03, p = 0.042) patients had higher odds of complications versus private (Table 3 M1). However, subgroup analysis for patients with a stoma showed similar odds of complications between all three insurance groups (Table 3 M2).

Increased 30-Day EDOS and Readmissions Among Medicaid/Uninsured Patients

Medicaid/uninsured patients had the highest rates of EDOS (16.6%, Table 1) and increased odds of EDOS (aOR = 4.81, CI = 2.57–10.06, p < 0.001) in all cases versus private after adjusting for frailty, open abdomen vs. laparoscopic surgery, urgent/emergent cases, and stoma (Table 3 M1). In the stoma subgroup, Medicaid/uninsured patients (aOR = 3.94, CI = 1.72–10.70, p = 0.003) had higher odds of EDOS (Table 3 M2). Medicaid/uninsured patients in the all cases group continued to have higher odds of EDOS (aOR = 4.66, CI = 2.47–9.75, p < 0.001) even after adjusting for complications (Table 3 M3).

Odds of readmission (Table 3 M1) were increased with open abdominal surgeries (aOR = 1.73, CI = 1.20–2.51, p = 0.004) and having a stoma (aOR = 2.83, CI = 2.00–4.03, p < 0.001). Medicaid/uninsured patients demonstrated the highest rates of readmissions (22.9%; Table 1) and increased odds of readmissions (aOR = 1.62, CI = 1.07–2.50, p = 0.025) in all cases versus private after adjusting for frailty, open abdomen vs. laparoscopic surgery, urgent/emergent cases, and stoma (Table 3 M1). However, readmission odds in Medicaid/uninsured versus private were similar in the stoma subgroup (Table 3 M2) and also in the all cases group after adjusting for complications (Table 3 M3).

Sensitivity Analyses of Clinical Outcomes

Sensitivity analyses added 34 cases initially excluded with no or reduced chances of subsequent EDOS and readmissions. The expanded cohort was assessed using the clinical outcome variables present in Tables 2 and 3. Results were similar between the original and expanded sensitivity analysis cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Cost Analyses

Decreased Index Hospitalization Variable Costs Among Patients with a 30-Day EDOS or Readmission

The %change of variable costs was higher for open abdomen versus laparoscopic cases (Supplemental Table 4 M1–M3). Medicaid/uninsured patients (12.1%, Supplemental Table 4 M1) had higher %changes in variable costs versus private but were similar after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases while Medicare patients had 11.2% higher costs versus private (Supplemental Table 4 M3). Having a stoma (32.0–55.3%), experiencing any complication (66.1–67.6%) and urgent/emergent cases (28.7%) increased index hospitalization costs. Patients with an EDOS and/or readmission versus those without had decreased (− 9.1 to − 10.8%) index hospitalization costs (Supplemental Table 4 M2 and M3).

Decreased Index Hospitalization LOS Among Patients with a 30-Day EDOS or Readmission

The %change of LOS was higher for open abdomen versus laparoscopic cases and higher for patients with a stoma (Supplemental Table 5 M1–M3). After adjusting for complications and urgent/emergent cases, patients with a readmission and/or EDOS had lower relative difference LOS, than those without (Supplemental Table 5 M2 and M3). Medicaid/uninsured patients (16.9%, Supplemental Table 5 M1) had higher %changes in LOS versus private until adjusting for any complication and urgent/emergent cases (Supplemental Table 5 M3).

Similar First EDOS and Readmission Costs between Private, Medicare, and Medicaid/Uninsured patients

The %change of the first EDOS and first readmission variable costs was similar for Medicare and Medicaid/uninsured versus private (Supplemental Table 6). The %change of the first readmission variable costs increased by 82.3% and 35.9% for cases experiencing any complication or were urgent/emergent, respectively.

Increased Numbers of 30-Day EDOS and Readmissions in Medicaid/Uninsured Patients

Both Medicare and Medicaid/uninsured had increased rates of patients with EDOS, readmissions, and with both EDOS and readmission versus private. Medicaid/uninsured patients had the highest returns/case in each category (EDOS 0.22, readmissions 0.27, both 0.49; Table 4). Medicaid/uninsured patients had more successive EDOS and readmissions versus private. Multiple Medicaid/uninsured cases had between three and six EDOS within 30 days of discharge, as well as one case having four readmissions; none of the private or Medicare cases exhibited this increased frequency of multiple encounters.

Increased Cumulative Variable Costs Among Patients with a 30-Day EDOS or Readmission

Both Medicare (17.0%) and Medicaid/uninsured patients (10.8%) had higher %changes in cumulative costs versus private (Table 5 M1), but only Medicaid/uninsured was similar to private after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases (Table 5 M3). Patients with a 30-day readmission and/or EDOS had higher %change (34.5%, Table 5 M1) than those without either even after adjusting for complications (14.8%, Table 5 M2) and urgent/emergent cases (16.9%, Table 5 M3). Stoma (31.3%), any complication (73.8%), and urgent/emergent cases (28.5%) increased cumulative hospitalization costs (Table 5 M3).

Increased Cumulative Return Costs Among Medicaid/Uninsured Patients

Medicaid/uninsured patients (138.7 to 181.4%) had increased %change in cumulative return costs versus private, even after adjusting for complications and urgent/emergent cases (Table 6, M1-M3).

Increased Mean and Median Cumulative Variable Costs Among Medicare and Medicaid/Uninsured Patients

Descriptive statistics for mean and median dollars for the cumulative variable costs of the index hospitalization and all 30-day EDOS and readmissions were reported due to the right skewed variable costs. Mean and median variable costs increased with open abdomen and urgent/emergent cases versus laparoscopic and elective cases, respectively in all three insurance groups (Table 7). Medicare, Medicaid/uninsured, and private mean variable costs were highest, intermediate and lowest, respectively, for all cases and each of the subgroups.

Discussion

This study comprehensively assessed the association of insurance type with EDOS, readmissions, and cumulative variable costs across CRS at an academic, SNH serving a diverse range of SES patients. Increased odds of complications, index hospitalization, return, and cumulative costs present in Medicaid/uninsured patients were driven by higher rates and increased odds of urgent/emergent cases. Urgent/emergent cases were associated with higher odds of having a stoma and open abdominal procedures; further contributing to the increased odds of complications, EDOS, and readmissions. However, the three insurance groups had similar odds of complications in the stoma subgroup, suggesting that the need to create a stoma was the driving factor in outcomes, rather than insurance type.

Increased index hospitalization and cumulative variable costs among Medicaid/uninsured insurance patients were similar to private after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases, while Medicare patients had higher %change even after adjusting for case status. Demographics for age and frailty scores were similar between private and Medicaid/uninsured patients, compared to Medicare patients whom were older with higher frailty scores potentially contributing to the increased costs. Open abdominal procedures, presence of a stoma, complications, and urgent/emergent cases were associated with increased index hospitalization and cumulative costs. The variation in index hospitalization costs by insurance type was consistent with prior studies49 including complications having the highest associated costs.50,51 Our study demonstrated that Medicaid/uninsured patients undergo more urgent/emergent surgeries, increasing the odds of open abdominal surgery, which was associated with more complications and higher costs versus private. Medicare and Medicaid/uninsured patients cost more and reimburse less than patients with private insurance.52,53

This study is one of the first to evaluate the return and cumulative costs of multiple EDOS and readmissions. While the 1st EDOS and readmission costs were similar across insurance type, return costs were 154% higher for Medicaid/uninsured patients due to the increased frequency of EDOS and readmission encounters even after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases. Medicaid/uninsured patients had higher odds of readmissions versus private after adjusting for urgent/emergent cases but not after adjusting for complications. Our Medicaid/uninsured group included patients with dual enrollment in Medicare/Medicaid. The use of readmissions as a quality metric has serious implications. Patient factors,54 urgent/emergency surgeries,55,56 and complications after discharge57 are major factors driving readmissions and return visits. Though SNH have higher readmission rates,25 studies show SNH provide similar quality care to low-burden hospitals.58,59,60,61 However, multiple studies demonstrate that SNH are disproportionately penalized by HRRP,22,23,62 worsening disparities between SNH that largely care for vulnerable populations.17,23 The increased index hospitalization, cumulative, and return costs and penalties for worse outcomes22,23,62 further strain resources at SNH. Including risk adjustment for urgent and emergent cases and could improve the accuracy of quality metrics. A possible solution to decreasing costs from urgent/emergent surgeries is improving outpatient and preventive care for Medicaid/Uninsured patients. Furthermore, the use of readmissions as a quality metric has been criticized as readmissions are heavily influenced by medical conditions and social factors that hospitals and clinicians cannot reasonably control.63 While the majority of procedures in our cohort are not covered by HRRP, we think it is important to study surgical readmissions to inform future decisions by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and private insurance companies regarding expanding or initiating readmissions policies.

Medicaid/uninsured patients had higher odds of EDOS versus private even after adjusting for complications. Studies suggest that many emergency department visits after CRS could be prevented.64,65,66 Our data suggests that Medicaid/uninsured patients are using the emergency department as substitute for outpatient care, further adding to costs.

Limitations

This study used a retrospective cohort and does not establish causal relationships. NSQIP provides a representative sample of surgeries but does not include all procedures for a healthcare system. This study only examined the clinical outcomes and costs observed by a single institution. Outside hospital EDOS and readmissions were not included secondary to missing cost data and our focus was on the impact of Medicaid/uninsured patients on SNH costs. We used complications available in NSQIP; various surgeries have specific complications not included in these analyses.

Conclusions

Increased rates and odds of urgent/emergent colorectal cases in Medicaid/uninsured populations drive increased odds of complications and higher index hospitalization and cumulative costs versus private patients suggesting lack of access to outpatient care. Return costs were were 154% higher for Medicaid/uninsured patients versus private due to the increased frequency of EDOS and readmission encounters. SNH care for higher cost populations while receiving lower reimbursements and are further penalized by current value-based programs such as HRRP. Increasing access to care for Medicaid/uninsured patients could reduce urgent/emergent surgeries resulting in fewer complications, EDOS/readmissions, and costs.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Schmidt reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Veterans Health Administration. Dr. Shireman reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Veterans Health Administration and salary support from Texas A&M University, South Texas Veterans Health Care System and the University of Texas Health San Antonio during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Disclaimer

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the United States government.

Data Availability

The data for this study is not available as it contains proprietary cost data and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

References

Bamdad MC, Brown CS, Kamdar N, Weng W, Englesbe MJ, Lussiez A. Patient, Surgeon, or Hospital: Explaining Variation in Outcomes after Colectomy. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2022;234(3):300-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/xcs.0000000000000063.

Lumpkin ST, Strassle PD, Fine JP, Carey TS, Stitzenberg KB. Early Follow-up After Colorectal Surgery Reduces Postdischarge Emergency Department Visits. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(11):1550-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001732.

Hyde LZ, Al-Mazrou AM, Kuritzkes BA, Suradkar K, Valizadeh N, Kiran RP. Readmissions after colorectal surgery: not all are equal. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(12):1667-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3150-3.

Damle RN, Cherng NB, Flahive JM, Davids JS, Maykel JA, Sturrock PR et al. Clinical and financial impact of hospital readmissions after colorectal resection: predictors, outcomes, and costs. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(12):1421-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000251.

Wang W, Hoyler MM, White RS, Tangel VE, Pryor KO. Hospital Safety-Net Burden Is Associated With Increased Inpatient Mortality and Perioperative Complications After Colectomy. J Surg Res. 2021;259:24-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.11.029.

Carmichael H, Dyas AR, Bronsert MR, Stearns D, Birnbaum EH, McIntyre RC et al. Social vulnerability is associated with increased morbidity following colorectal surgery. Am J Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.03.010.

Arya S, Varley P, Youk A, Borrebach JD, Perez S, Massarweh NN et al. Recalibration and External Validation of the Risk Analysis Index: A Surgical Frailty Assessment Tool. Ann Surg. 2020;272(6):996-1005. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003276.

Fagard K, Leonard S, Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Wolthuis A, Prenen H et al. The impact of frailty on postoperative outcomes in individuals aged 65 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(6):479-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.06.001.

Robinson TN, Wu DS, Stiegmann GV, Moss M. Frailty predicts increased hospital and six-month healthcare cost following colorectal surgery in older adults. Am J Surg. 2011;202(5):511-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.06.017.

Visenio MR, Bilimoria KY, Merkow RP. Surgical Cancer Care for Dually Eligible Beneficiaries: Taking Care of America's Vulnerable Patients. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(4):e217587. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.7587.

Taylor K, Diaz A, Nuliyalu U, Ibrahim A, Nathan H. Association of Dual Medicare and Medicaid Eligibility With Outcomes and Spending for Cancer Surgery in High-Quality Hospitals. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(4):e217586. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.7586.

Diaz A, Hyer JM, Barmash E, Azap R, Paredes AZ, Pawlik TM. County-level Social Vulnerability is Associated With Worse Surgical Outcomes Especially Among Minority Patients. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):881-91. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000004691.

Hyde LZ, Valizadeh N, Al-Mazrou AM, Kiran RP. ACS-NSQIP risk calculator predicts cohort but not individual risk of complication following colorectal resection. Am J Surg. 2019;218(1):131-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.11.017.

Sastow DL, White RS, Mauer E, Chen Y, Gaber-Baylis LK, Turnbull ZA. The Disparity of Care and Outcomes for Medicaid Patients Undergoing Colectomy. J Surg Res. 2019;235:190-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.056.

LaPar DJ, Bhamidipati CM, Mery CM, Stukenborg GJ, Jones DR, Schirmer BD et al. Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):544–50; discussion 50–1. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e8fd75.

Thompson MP, Waters TM, Kaplan CM, Cao Y, Bazzoli GJ. Most Hospitals Received Annual Penalties For Excess Readmissions, But Some Fared Better Than Others. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):893-901. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1204.

Glance LG, Kellermann AL, Osler TM, Li Y, Li W, Dick AW. Impact of Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status on Risk-adjusted Surgical Readmission Rates. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):698-704. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001363.

Hospitalization Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). www.cms.gov. 2019. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed 2–22–2022 2022.

Banerjee S, Paasche-Orlow MK, McCormick D, Lin MY, Hanchate AD. Readmissions performance and penalty experience of safety-net hospitals under Medicare's Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07741-9.

Zogg CK, Thumma JR, Ryan AM, Dimick JB. Medicare's Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program Disproportionately Affects Minority-serving Hospitals: Variation by Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Disproportionate Share Hospital Payment Receipt. Ann Surg. 2020;271(6):985-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003564.

Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Hu J, Kind AJH, Zaslavsky AM, Nagasako EM et al. Adjusting for social risk factors impacts performance and penalties in the hospital readmissions reduction program. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):327-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13133.

Favini N, Hockenberry JM, Gilman M, Jain S, Ong MK, Adams EK et al. Comparative Trends in Payment Adjustments Between Safety-Net and Other Hospitals Since the Introduction of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program and Value-Based Purchasing. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1578-80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.1469.

Shih T, Ryan AM, Gonzalez AA, Dimick JB. Medicare's Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in Surgery May Disproportionately Affect Minority-serving Hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(6):1027-31. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000778.

Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of Hospitals Receiving Penalties Under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342-3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.94856.

McCarthy CP, Vaduganathan M, Patel KV, Lalani HS, Ayers C, Bhatt DL et al. Association of the New Peer Group-Stratified Method With the Reclassification of Penalty Status in the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192987. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2987.

Kao LS, Dimick JB, Porter GA. How do administrative data compare with a clinical registry for identifying 30-day postoperative complications? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(6):1187-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.09.002.

Lawson EH, Zingmond DS, Hall BL, Louie R, Brook RH, Ko CY. Comparison between clinical registry and medicare claims data on the classification of hospital quality of surgical care. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):290-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000707.

Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Jr., Steeger JE, Rowell KS, Bartzokis K, Tomeh MG et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):6-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031.

Navar AM, Peterson ED, Steen DL, Wojdyla DM, Sanchez RJ, Khan I et al. Evaluation of Mortality Data From the Social Security Administration Death Master File for Clinical Research. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(4):375-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0198.

Yan Q, Kim J, Hall DE, Shinall MC, Jr., Reitz KM, Stitzenberg KB et al. Association of Frailty and the Expanded Operative Stress Score with Preoperative Acute Serious Conditions, Complications and Mortality in Males Compared to Females: A Retrospective Observational Study. Ann Surg. 2023;227(2):e294-e304. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000005027.

Rothenberg KA, Stern JR, George EL, Trickey AW, Morris AM, Hall DE et al. Association of Frailty and Postoperative Complications With Unplanned Readmissions After Elective Outpatient Surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194330. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4330.

Hall DE, Arya S, Schmid KK, Blaser C, Carlson MA, Bailey TL et al. Development and Initial Validation of the Risk Analysis Index for Measuring Frailty in Surgical Populations. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):175-82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4202.

Ghirimoldi FM, Schmidt S, Simon RC, Wang CP, Wang Z, Brimhall BB et al. Association of Socioeconomic Area Deprivation Index with Hospital Readmissions After Colon and Rectal Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(3):795-808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04754-9.

George EL, Hall DE, Youk A, Chen R, Kashikar A, Trickey AW et al. Association Between Patient Frailty and Postoperative Mortality Across Multiple Noncardiac Surgical Specialties. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):e205152. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5152.

George EL, Massarweh NN, Youk A, Reitz KM, Shinall MC, Jr., Chen R et al. Comparing Veterans Affairs and Private Sector Perioperative Outcomes After Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6488.

Reitz KM, Varley PR, Liang NL, Youk A, George EL, Shinall MC, Jr. et al. The Correlation Between Case Total Work Relative Value Unit, Operative Stress, and Patient Frailty: Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2021;274(4):637-45. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000005068.

Shinall MC, Jr., Arya S, Youk A, Varley P, Shah R, Massarweh NN et al. Association of Preoperative Patient Frailty and Operative Stress With Postoperative Mortality. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(1):e194620. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4620.

Shinall MC, Jr., Youk A, Massarweh NN, Shireman PK, Arya S, George EL et al. Association of Preoperative Frailty and Operative Stress With Mortality After Elective vs Emergency Surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2010358. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10358.

Mullen MG, Michaels AD, Mehaffey JH, Guidry CA, Turrentine FE, Hedrick TL et al. Risk Associated With Complications and Mortality After Urgent Surgery vs Elective and Emergency Surgery: Implications for Defining "Quality" and Reporting Outcomes for Urgent Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):768-74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0918.

Roberts RR, Frutos PW, Ciavarella GG, Gussow LM, Mensah EK, Kampe LM et al. Distribution of variable vs fixed costs of hospital care. JAMA. 1999;281(7):644-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.7.644.

Chandra C, Kumar S, Ghildayal NS. Hospital cost structure in the USA: what's behind the costs? A business case. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(4):314-28. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526861111125624.

Reinhardt UE. Spending more through 'cost control:' our obsessive quest to gut the hospital. Health Aff (Millwood). 1996;15(2):145-54. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.15.2.145.

Kalman N HB, Schulman K, Shah B. . Hospital overhead costs: the neglected driver of health care spending? . J Health Care Finance. 2015;41(4).

Kim J, Jacobs MA, Schmidt S, Brimhall BB, Salazar CI, Wang CP et al. Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing Surgical Inpatient Charges, Total Costs, and Variable Costs as Hospital Cost Savings Measures. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(50):e3207.

Denton TA, Luevanos J, Matloff JM. Clinical and nonclinical predictors of the cost of coronary bypass surgery: potential effects on health care delivery and reimbursement. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(8):886-91. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.8.886.

Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting Health Expenditures for Inflation: A Review of Measures for Health Services Research in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(1):175-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12612.

Keller DS, Swendseid B, Khorgami Z, Champagne BJ, Reynolds HL, Jr., Stein SL et al. Predicting the unpredictable: comparing readmitted versus non-readmitted colorectal surgery patients. Am J Surg. 2014;207(3):346-51; discussion 50-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.09.008.

Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O'Hagan A, Thompson SG. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 2011;20(8):897-916. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1653.

Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Bear HD. Insurance and inpatient care: differences in length of stay and costs between surgically treated cancer patients. Cancer. 2012;118(20):5084-91. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27508.

Selby LV, Gennarelli RL, Schnorr GC, Solomon SB, Schattner MA, Elkin EB et al. Association of Hospital Costs With Complications Following Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):953-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1718.

Healy MA, Mullard AJ, Campbell DA, Jr., Dimick JB. Hospital and Payer Costs Associated With Surgical Complications. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(9):823-30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0773.

Hartman M, Martin A, Nuccio O, Catlin A. Health spending growth at a historic low in 2008. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):147-55. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0839.

Levit K, Smith C, Cowan C, Sensenig A, Catlin A. Health spending rebound continues in 2002. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(1):147-59. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.147.

Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding Variation in 30-Day Surgical Readmission in the Era of Accountable Care: Effect of the Patient, Surgeon, and Surgical Subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2215.

Hoehn RS, Wima K, Vestal MA, Weilage DJ, Hanseman DJ, Abbott DE et al. Effect of Hospital Safety-Net Burden on Cost and Outcomes After Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(2):120-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3209.

Hajirawala L, Leonardi C, Orangio G, Davis K, Barton J. Urgent Inpatient Colectomy Carries a Higher Morbidity and Mortality Than Elective Surgery. J Surg Res. 2021;268:394-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.06.081.

Morris MS, Deierhoi RJ, Richman JS, Altom LK, Hawn MT. The relationship between timing of surgical complications and hospital readmission. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(4):348-54. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4064.

Ando T, Adegbala O, Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Takagi H. The impact of safety-net burden on in-hospital outcomes after surgical aortic valve replacement. J Card Surg. 2019;34(11):1178-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocs.14187.

Lopez RC, Rennert RC, Brandel MG, Abraham P, Hirshman BR, Steinberg JA et al. The effect of hospital safety-net burden on outcomes, cost, and reportable quality metrics after emergent clipping and coiling of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2019;132(3):788-96. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.10.Jns18103.

Hoyler MM, Tam CW, Thalappillil R, Jiang S, Ma X, Lui B et al. The impact of hospital safety-net burden on mortality and readmission after CABG surgery. J Card Surg. 2020;35(9):2232-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocs.14738.

Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1134-42. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1303118.

Ryan AM, Burgess JF, Jr., Pesko MF, Borden WB, Dimick JB. The early effects of Medicare's mandatory hospital pay-for-performance program. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):81-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12206.

Cram P, Wachter RM, Landon BE. Readmission Reduction as a Hospital Quality Measure: Time to Move on to More Pressing Concerns? JAMA. 2022;328(16):1589-90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.18305.

Eustache J, Hopkins B, Trepanier M, Kaneva P, Fiore JF, Fried GM et al. High incidence of potentially preventable emergency department visits after major elective colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08514-x.

Wong DJ, Roth EM, Sokas CM, Pastrana Del Valle JR, Fleishman A, Gaytan Fuentes IA et al. Preventable Emergency Department Visits After Colorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64(11):1417-25. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000002127.

Jones D, Musselman R, Pearsall E, McKenzie M, Huang H, McLeod RS. Ready to Go Home? Patients' Experiences of the Discharge Process in an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Program for Colorectal Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(11):1865-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3573-0.

Funding

This research was supported by grant U01TR002393 (Kim, Jacobs, Wang, Brimhall, Schmidt, Manuel, Damien, and Shireman), from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the Office of the Director, NIH, Clinical Translational Science Awards UL1TR002645 (Wang, Brimhall, Schmidt, Manuel, and Shireman) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH and P30AG044271 from the National Institute on Aging, NIH (Shireman and Brimhall).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Drs. Shireman and Kim, Mr. Jacobs, and Ms. Manuel had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Shireman, Schmidt, Jacobs, Kim, Brimhall, and Damien.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Tetley, Jacobs, and Shireman.

Critical revision for important intellectual content and final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Jacobs, Kim, Wang, and Damien.

Obtained funding: Shireman, Brimhall, Schmidt, Damien, and Wang.

Administrative, technical, or material support: all authors.

Supervision: Shireman.

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jacobs, M.A., Tetley, J.C., Kim, J. et al. Association of Cumulative Colorectal Surgery Hospital Costs, Readmissions, and Emergency Department/Observation Stays with Insurance Type. J Gastrointest Surg 27, 965–979 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-022-05576-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-022-05576-7