Abstract

Background

The frequency and management of gallstone disease (GD) in bariatric patients, including the role of routine prophylactic concomitant cholecystectomy (CCY), are still a matter of debate. This study aims to assess the risk of de novo GD in patients undergoing bariatric surgery (BS) and their predictive factors, as well as mortality and morbidity in prophylactic CCY compared to BS alone.

Methods

We performed a systematic review, searching PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science until April 2021. We performed a Bayesian meta-analysis to estimate the risk of GD development after BS and the morbidity and mortality associated with BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY. Sources of heterogeneity were explored by meta-regression analysis.

Results

The risk of de novo post bariatric GD was 20.7% (95% credible interval [95% CrI] = 13.0–29.7%; I2 = 75.4%), and that of symptomatic GD was 8.2% ([95% CrI] = 5.9–11.1%; I2 = 66.9%). Pre-operative average BMI (OR = 1.04; 95% CrI = 0.92–1.17) and female patients’ proportion (OR = 1.00; 95% CrI = 0.98–1.04) were not associated with increased risk of symptomatic GD.

BS + prophylactic CCY was associated with a 97% probability of a higher number of postoperative major complications compared to BS alone (OR = 1.74, 95% CrI = 0.97–3.55; I2 = 56.5%). Mortality was not substantially different between the two approaches (OR = 0.79; 95% CrI = 0.03–3.02; I2 = 20.7%).

Conclusion

The risk of de novo symptomatic GD after BS is not substantially high. Although mortality is similar between groups, odds of major postoperative complications were higher in patients submitted to BS + prophylactic CCY. It is still arguable if prophylactic CCY is a fitting approach for patients with a preoperative lithiasic gallbladder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery (BS) has been identified as the most effective treatment for clinically severe obesity, resulting in sustained weight loss and significant improvement in obesity-related comorbidities.1 Despite its benefits, BS is associated with a 3–28% incidence of symptomatic gallstone disease (GD),2 which is five times higher than the healthy population3.

Understanding the risk factors associated with GD development may be crucial for risk stratification and distinct patient management, especially since GD risk factors in the general population may not be predictive in patients submitted to BS.4, 5, 6

The varying incidence of symptomatic GD after BS has resulted in controversies regarding whether prophylactic concomitant cholecystectomy (CCY) should be performed. Currently, there are three approaches on this subject: (i) routine prophylactic cholecystectomy concomitant to BS for all patients (BS + prophylactic CCY), (ii) a selective prophylactic CCY only for those with positive findings on pre-operative ultrasound, and (iii) medical prophylactic treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).4,7,8 There may be some arguments in favor or against each of these options—for example, CCY could avoid stone-related complications, including further hospitalization and surgery; however, it is a technically challenging procedure. On the other hand, cholecystectomy after BS, for symptomatic GD, is also a procedure associated with technical difficulties.9,10 Despite these controversies, evidence on all of these options has not been systematically assessed.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to (objective i) quantify the risk of de novo asymptomatic or symptomatic GD after BS, (objective ii) identify predictive factors associated with de novo GD after BS, and (objective iii) compare the morbidity and mortality of BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY.

Material and Methods

This systematic review with meta-analysis follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines and the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews.11,12

Eligibility Criteria

We included observational studies assessing BS as an obesity treatment for patients with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities. For objectives i and ii (risk of de novo post-bariatric GD and its predictive factors), the outcome to be reported was GD development. It was defined as de novo episodes of symptomatic biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and acute pancreatitis, or de novo asymptomatic evidence of cholelithiasis on post-operative ultrasound. For objective iii (comparison of the morbidity and mortality of BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY), any of the following outcomes needed to be reported: postoperative mortality, duration of surgery, hospital length-of-stay (LOS), and major postoperative complications. BS + prophylactic CCY was defined as cholecystectomy concomitant to bariatric surgery for asymptomatic patients (with no or asymptomatic gallstones confirmed by preoperative ultrasound), who had not been submitted to a previous cholecystectomy.

More detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria, for each specific objective, are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Search Strategy

We searched three electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science) from inception until April 6, 2021 (when our search was performed). Search queries are detailed in Supplementary Table 2. This search was supplemented by a gray literature search (conference papers, clinical trials—ongoing or unpublished), as well as hand-searching references of primary studies and other relevant reviews that were included. No restrictions were set regarding language or publication year.

Study Selection and Data Collection Process

After removing duplicates, each study was independently assessed by two reviewers (F.C and M.R), first by title and abstract screening and then by full-text reading.

Two reviewers independently extracted data from selected studies using a predefined form purposely built for this systematic review. For each primary study, the following information was retrieved: authors’ identification, year of publication, country, study design, number of enrolled patients, type of performed BS, follow-up period, patients’ characteristics (distributions of gender, age, and pre-operative and post-operative body mass index (BMI)), frequency of co-morbidities, weight loss after surgery, and preoperative gallbladder status. The latter was classified as alithiasic or lithiasic gallbladder confirmed by ultrasonography. An alithiasic gallbladder was defined as a preoperative gallbladder without gallstones or sludge, and a lithiasic gallbladder was defined as a preoperative asymptomatic gallbladder with gallstones or sludge without being submitted to CCY.

For objectives i and ii (risk of de novo post-bariatric GD and its predictive factors), we also retrieved information on the number of patients: (i) at risk of GD, (ii) at risk of symptomatic GD only (with information retrieved also for the time to symptoms), (iii) who developed GD, (iv) who developed symptomatic GD only, (v) who developed each GD presentation (such as biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and acute pancreatitis), and (vi) undergoing postoperative cholecystectomy. Both patients with no symptoms of cholelithiasis and either preoperative negative gallstone findings or preoperative positive gallstone findings were at risk of de novo symptomatic GD. In contrast, only patients with preoperative negative gallstone findings and primarily asymptomatic were considered at risk for de novo asymptomatic GD. Whenever provided, we retrieved data separately based on preoperative gallbladder status. Data related to other biliary conditions, such as gallbladder carcinoma or polyps, were not retrieved.

For objective iii (comparison between BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY), the additional following information was concerned: (i) number of patients submitted to BS alone and BS + prophylactic CCY; (ii) reason for prophylactic CCY; (iii) surgery duration; (iv) LOS; (v) major postoperative complications (medical complications—cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), respiratory failure, pneumonia, sepsis, venous thromboembolism, acute renal failure, and bleeding requiring transfusion; surgical complications—anastomotic leakage, organ space surgical site infection, the conversion rate of laparoscopic surgery, number of reoperations, and hospital readmission within 30 days); and (vii) postoperative mortality.

If distinct eligible publications reported data on the same patient cohort, the more recent and largest cohort was included. Authors were contacted whenever full texts were not available or to provide the relevant missing information. In study selection or data extraction, any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consulting a third senior reviewer (H.S.S) to reach a final decision.

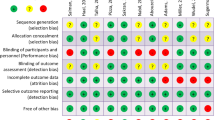

Quality Assessment

The quality of primary studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (F.C and M.R) using the National Institutes of Health quality assessment criteria for observational studies.13 To reach a consensus, divergent opinions regarding quality assessment were discussed with a third reviewer (H.S.S). This tool consists of a form with 14 yes-or-no questions (related to the research question, study population, exposure, outcome, blinding, follow-up, and statistical analysis) and a final quality rating (good, fair, or poor), classifying the study according to its potential risk of bias.13 The question about assessors being blinded regarding the exposure status was not possible to assess in any of the included studies.

Synthesis of Results

Given the inclusion of a large number of studies with no occurrence of events, we opted in performing a meta-analysis according to a Bayesian approach following a random-effects model based on a binomial likelihood.14 Compared to frequentist (“classical”) approaches, Bayesian meta-analysis deals more adequately with proportions equal to zero.

Bayesian methods provide estimations of posterior probability distributions of the parameters of interest, based on prior probability distributions and the observed data. In this study, for the risk of de novo post-bariatric GD, we computed the meta-analytical risk of GD and of symptomatic GD only. To compare outcomes between patients submitted to BS alone as index events versus those submitted to BS + prophylactic CCY, we computed meta-analytical odds ratio (OR) or mean differences (MD) depending on whether outcome variables were categorical or continuous, respectively. Of these results, we collected information on the mean values and respective 95% credible intervals (95% CrI; a range of values within which the true effect size measure lies, with a 95% probability).

Comparison between concomitant CCY and postoperative cholecystectomy was not quantitatively synthesized, due to the low number of available studies and substantial missing information.

Heterogeneity was assessed through an estimate of the I2 statistic—an I2 > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. Heterogeneity sources were explored through univariable meta-regression and subgroup analyses; – in particular, meta-regression allowed for the identification of potential predictive factors for the risk of de novo bariatric GD. Exponentials of the meta-regression coefficients were interpreted as OR. Finally, we also performed a separate meta-analysis for the development of symptomatic GD among patients with preoperative lithiasic versus alithiasic gallbladder.

For both the effect size measure and the τ parameter, we used uninformative prior distributions (dnorm (0, 0.00001) and dgamma (0.00001, 0.00001), respectively). We ran at least 40,000 iterations for each analysis with a burn‐in of 15,000 sample iterations. Meta‐analysis was performed using the rjags package of software R (version 3.5.0).

Results

Study Selection

The electronic literature search resulted in 5082 articles, of which 1808 were duplicates. After excluding 3184 records in the screening phase, 90 articles were fully read, of which a total of 42 were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).5,7,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 Hand-searching resulted in 23 additional articles, of which 8 were included.56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64 Ten authors were asked for additional information, as outcomes of interest were missing. Seven did not answer, and their studies were excluded from objectives i and ii. In total, 50 articles were included—39 for answering objectives i and ii (assessment of the risk of de novo symptomatic or asymptomatic GD and its predictive factors)5,7,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,51,52,55,56,58,62 and 14 for objective iii (comparing BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY).16,25,38,47,50,51,52,53,54,59,60,61,62,64

Flow diagram of study selection. BS, bariatric surgery; UDCA, Ursodeoxycholic acid; BS + CCY, prophylactic cholecystectomy concomitant to bariatric surgery; CY, cholecystectomy. aThis exclusion criteria is not applicable if patients with gallbladder in situ were individually reported. Objective i/ii—risk of de novo asymptomatic or symptomatic GD after BS and its predictive factors; objective iii—comparison of morbidity and mortality of BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY. 3 studies (Kim et al.; Tucker et al., Wanjura et al.) were used for 3 study objectives

Study Characteristics

A summary of included studies is presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3. The remaining characteristics are reported in Supplementary Table 3.1–3.4.

For objectives i and ii, included studies were published between 2004 and 2019, with a cumulative sample size of 64,950 patients. Most were retrospective cohort studies (n = 24, 61.5%). The mean participants’ age was 40.9 years (SD = 9.3 years) with a female predominance (74.0%). Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGBP) was the most-performed BS type (13 studies, n = 46, 313, 71.3%). The mean follow-up period was of 29.0 months.

For objective iii, included studies were published between 1995 and 2006, with a cumulative sample size of 685,994 patients. Open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) was the most-performed BS type (5 studies, n = 653 405, 95.2%). Among patients undergoing prophylactic CCY (n = 26 461, 4%), 44% had negative findings for GD in pre-operative ultrasonography.

Risk of Developing De Novo Gallstone Disease

A total of 38,210 asymptomatic patients with only preoperative negative GD findings were at risk of de novo postoperative GD. The Bayesian meta‐analysis identified a post-bariatric risk of de novo GD of 20.7% (95% credible interval [95% CrI] = 13.0–29.7%), even though with severe heterogeneity (I2 = 75.4%). A higher BMI was associated, – with a 96% probability, – with higher odds of de novo GD (OR = 1.11; 95% CrI = 0.99–1.22). Other results of univariable meta-regression are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

A total of 63 938 asymptomatic patients with either preoperative negative or positive gallstone findings were at risk of de novo symptomatic GD. A total of 3312 developed symptomatic GD, corresponding to a meta-analytical risk of 8.2% (95% CrI = 5.9–11.1%), even though with high heterogeneity (I2 = 66.9%, Table 4). The three most common clinical presentations were biliary colic (n = 1559, 65.5%), cholecystitis (n = 120, 14.7%), and symptomatic choledocholithiasis (n = 37, 4.5%) (Supplementary Table 3.1). Almost all patients required postoperative cholecystectomy (n = 3 179, 96%). The results of univariable meta-regression and subgroup analyses are presented in Table 4. Regarding studies’ methodological characteristics, retrospective studies were associated, – with a 94% probability,—with lower odds of de novo symptomatic GD (OR = 0.60; 95% CrI = 0.31–1.10).

Pre-operative average BMI (OR = 1.04; 95% CrI = 0.92–1.17) and female patients’ proportion (OR = 1.00; 95% CrI = 0.98–1.04) did not impact the risk of de novo symptomatic GD. Although none of the assessed bariatric surgery types had a strong impact on GD risk, laparoscopic gastric banding (LAGB) was associated, – with an 82% probability,—with lower odds of de novo symptomatic GD. Insufficient data on co-morbidities and weight loss after surgery did not allow meta-regression analysis models to include these variables.

Comparison between bariatric surgery alone versus prophylactic cholecystectomy concomitant to bariatric surgery

Bayesian meta‐analysis identified that postoperative mortality was not substantially different between BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY (OR = 0.79; 95% CrI = 0.03–3.02; I2 = 20.7%). BS + prophylactic CCY was associated with 97% probability of a higher number of postoperative major complications compared to BS alone (OR = 1.74, 95% CrI = 0.97–3.55; I2 = 56.5%). The odds of organ space surgical site infection were similar between groups (OR = 0.97, 95% CrI = 0.05–4.71; I2 = 52.8%) (Table 5). Insufficient data on some complications, namely the conversion rate of laparoscopic surgery and hospital readmissions within 30 days did not allow such outcomes to be analyzed through meta-analysis.

Univariable meta-regression results are presented in Table 6. Neither age (OR = 1.22, 95% CrI = 0.87–1.68) nor female patients’ proportion (OR = 0.95, 95% CrI = 0.87–1.04) were associated with a relevant impact on the association between BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY on the occurrence of postoperative major complications. Although any type of bariatric surgery had no strong impact on postoperative major complications, they slightly changed through bariatric procedures—laparoscopic gastric banding (LAGB) was the one associated with lower chances (87%) of postoperative major complications between BS + prophylactic CCY versus BS alone (OR = 0.42, 95% CrI = 0.04–1.97). Moreover, prophylactic cholecystectomy concomitant to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), compared to prophylactic cholecystectomy concomitant laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGBP) (OR = 0.66, 95% CrI = 0.16–2.59 versus OR = 2.33, 95% CrI = 0.28–10.27), had a tendentially lower probability of postoperative major complications. Regarding Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, comparing open and laparoscopic approaches, the probability of postoperative major complications was not too dissimilar (OR = 1.64, 95% CrI = 0.33–4.80 versus OR = 2.33, 95% CrI = 0.28–10.27).

Patients submitted to BS + prophylactic CCY had a longer operative time—more than 29.2 min (95% CrI = 17.9–40.7), even though there was severe heterogeneity found (I2 = 89.3%). There were no relevant differences in hospital LOS (MD = − 0.1 days; 95% CrI = − 1.0–0.5; I2 = 74.3%) (Table 5).

Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

The results of the risk of bias assessments for included primary studies are presented in Table 1, and a detailed description is reported in Supplementary Table 5.1 and Table 5.2. Most studies (n = 47, 94%) did not justify the sample size, and 39 studies (78%) did not adjust for any potential confounding variables. For the remaining parameters, most studies were associated with a low risk of bias. Bastouly et al.56 were considered to have a high risk of bias, namely selection bias since patients were selectively invited.

In fact, when considering only high-quality studies, the risk of symptomatic GD is of 7.5% (95% CrI = 5.2–10.6%; I2 = 59.1%). Such a trend was not observed for asymptomatic or symptomatic GD. Having a high risk of bias was also related,—with 93% probability,—with a weak association between BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY on the occurrence of postoperative major complications (OR 0.49; 95% CrI = 0.16–1.27).

Discussion

The main findings of our study were the following: (1) the risk of developing de novo symptomatic gallstone disease after BS is not substantially high (8.2%), although three times higher than the healthy population; (2) GD predictive factors after BS are not similar to those of the general population, except for preoperative average of BMI in asymptomatic or symptomatic GD; and (3) patients who underwent prophylactic CCY had a longer operative time and a higher rate of postoperative complications than those who underwent BS alone, but mortality and hospital LOS were similar.

Some of the pathogenic mechanisms that can explain why patients after BS are at risk of developing GD include an increased biliary cholesterol concentration following rapid weight loss, gallbladder hypomotility secondary to vagal nerve resection and a decreased cholecystokinin secretion, an increased secretion of calcium and biliary mucin, and a disturbed enterohepatic circulation of biliary salts.5,6,37,65 Our meta-analysis showed that the risk of developing symptomatic GD is 8.2%, in a mean follow-up of 29.0 months. Warschkow et al.8 reported a similar percentage (6.8%), although the cumulative sample size was lower and only LRYGBP was performed. Our risk might be slightly underestimated since a clear decrease in the risk of de novo symptomatic GD was observed for retrospective studies, which might be explained by information bias. In fact, considering only prospective studies, this risk rises to 11.2%. Therefore, our findings, regarding the risk of developing symptomatic GD after BS, may call into question the pertinence of prophylactic CCY. Theoretically, one of the reasons to routinely perform cholecystectomy concomitant to BS concerns the prevention of later biliary complications (symptomatic choledocholithiasis, acute cholangitis, and biliary pancreatitis), mainly because endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is routinely impossible to perform after LRYGBP.8,66 In the present study, similar to other meta-analyses,8,67 symptomatic choledocholithiasis occurred in 37 patients (4.5%) and acute pancreatitis in 23 (2.8%). As a rare event, it does not uphold a prophylactic CCY.

Understanding predictive factors for gallstone formation after BS could influence distinct patient management, including a selective approach for BS + prophylactic CCY. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis exploring this topic. Through meta-regression and subgroup analyses, we found that neither higher pre-operative BMI, nor female patients’ proportion appear to be risk factors. However, we were only able to assess data at the study level. Assessing whether having a high BMI or being a female as risk factors for GD development would require an assessment of individual participant data. In our study, LAGB was associated with lower odds of de novo symptomatic GD. This could be explained by the fact that this restrictive bariatric procedure does not alter gastrointestinal transit, biliary contraction mechanisms, and enterohepatic circulation.36,68 On the contrary, in the RYGBP procedure, the altered anatomy, the division of the vagus nerve, and reduced cholecystokinin may lead to gallbladder dysmotility.18,69 It was not possible to understand the association between symptomatic GD and excessive weight loss. Although rapid weight loss is classically pointed to as the main predictive factor,7 it is not consensual across individual studies.4,6,26,27,36

We performed a separate meta-analysis to understand the impact of preoperative gallbladder status (lithiasic versus alithiasic) in the development of symptomatic GD. There is a 30% probability of symptomatic GD being more common in patients with preoperative lithiasic gallbladder than with preoperative alithiasic gallbladder (OR = 1.51; 95% CrI = 0.31–3.77). Moreover, according to the literature, severe biliary complications after bariatric surgery (symptomatic choledocholithiasis, acute cholangitis, and biliary pancreatitis) are more common in patients with asymptomatic preoperative gallstones.70,71 These arguments might reinforce a more selective approach, where patients with asymptomatic GD would undergo prophylactic CCY, given that, after RYGBP, ERCP is impossible to perform. However, from an expectant management perspective, surgery would be avoided in 88% of these patients and, consequently morbidity of a concomitant procedure. Furthermore, as ultrasound has a low sensibility in patients with obesity, there is no ideal screening method for patient selection. In meta-regression, studies enrolling only patients with alithiasic gallbladders were associated with higher odds of de novo symptomatic GD compared to studies enrolling patients with alithiasic and lithiasic gallbladders. These two approaches (separate meta-analysis versus meta-regression) may seem to contradict each other. However, the first approach evaluates individual participant data, whereas the second evaluates data at a study level, aiming to measure covariable impact in heterogeneity.

Regarding safety, we observed similar results in postoperative mortality and hospital LOS in patients submitted to BS + prophylactic CCY in comparison to BS alone. On the other hand, operative time and odds of postoperative major complications were higher in patients submitted to BS + prophylactic CCY. Concomitant cholecystectomy is a technically challenging procedure, which could account for these findings. Gallbladder position, often embedded in a steatosis liver, the inadequate position of the trocars, and operator fatigue are some issues to be pointed out.4,66,72 It is worth mentioning that there could be a selection bias present, when assessing the outcome operation BS + prophylactic CCY. In some studies,38,51,62 patients had an indication for prophylactic CCY, but the procedure was abandoned due to insufficient exposure of the right upper quadrant, patients’ comorbidities, surgeon preference, or technical difficulties. Other meta-analyses reached identical results,10,67,70,73 but it is worth noting that these authors studied cholecystectomy concomitant to bariatric surgery for both prophylactic and symptomatic management.

Our results should be interpreted with caution, owing to the observed heterogeneity, which suggests important differences between studies.

Through meta-regression, covariates such as age and the proportion of females did not have a relevant impact on the association between BS alone versus BS + prophylactic CCY in concern to postoperative major complications. We also found that no type of bariatric surgery had a strong impact on postoperative major complications. In the open RYGBP era, prophylactic concomitant cholecystectomy was advocated due to the higher risk of symptomatic gallstone disease, technical difficulties in re-operation, and low morbidity with concomitant cholecystectomy. With current minimally invasive procedures, postoperative major complications seem to outdo the relatively low incidence of symptomatic gallstone.7,51 There are only a few studies and no systematic reviews comparing postoperative complications between LSG and LRYGBP with prophylactic CCY. Based on our data, the addition of prophylactic CCY either to LSG or LRYGBP was not associated with an increase in major complications.

Postoperative cholecystectomy safety could modify the perspective regarding prophylactic CY. While it would have been interesting to explore the morbidity and mortality of BS + prophylactic CCY versus postoperative cholecystectomy, we were not able to perform a meta-analysis due to a limited number of studies. Reduced intra-abdominal fat and liver size after BS26 make delayed cholecystectomy technically easier to perform. Warschkow et al.8 found that the risk of suffering a complication during subsequent cholecystectomy is only 0.1%. Randomized controlled studies are still needed to assess surgical complications, operative time, LOS, and mortality associated with subsequent cholecystectomy.

This systematic review has some limitations worth noting. First, severe heterogeneity was found, explained by different study designs and eligibility criteria. To explore possible sources of heterogeneity, meta-regression and subgroup analysis were preformed, even though they did not account for all heterogeneity. The impact of distinct exclusion criteria, mainly in objectives i and ii (risk of de novo post-bariatric GD and its predictive factors), might be an explanation—some authors18,32,58 excluded patients with preoperative positive findings for GD in ultrasonography, while others20,23,29 did not, leading to a possible overestimation of GD development. Second, this systematic review lacks randomized controlled trials to provide strong evidence to support our findings. Third, almost half of the included studies did not have a low risk of bias, which could impact our results on the risk of de novo GD and postoperative complications rate, particularly, as the quality of the primary studies’ was found to be a moderator variable of heterogeneity.

There are also strengths in our study. The main methodological strength of this study is its meta-analytical approach to quantitative synthesis. The main advantage of Bayesian meta‐analysis is its use of exact methods, dealing more adequately with zero‐cells. Second, we performed a comprehensive search, encompassing three different electronic bibliographic databases and not using exclusion criteria based on the date or language of publication. Third, regarding eligibility criteria, to estimate the risk of post-bariatric de novo GD, studies that included prophylactic treatment with UDCA after BS or patients submitted to cholecystectomy prior or concomitant to BS, were excluded avoiding the risk of underestimation. Finally, meta-regression and subgroup analysis allowed the identification of predictive factors for gallstone formation.

In conclusion, after BS, the risk of developing GD is not substantially high, and severe biliary complications are extremely rare. Although there were no substantial differences in postoperative mortality or hospital length-of-stay, the determined risk of symptomatic GD and the higher risk of postoperative complications do not seem to justify performing prophylactic CCY in patients with alithiasic gallbladder. Doubts remain if a selective approach is advantageous since patients with preoperative gallbladder pathology have some increased risk of symptomatic GD. Randomized controlled studies might be considered to further clarify the role of prophylactic CCY as a selective approach. For future studies, we make the following recommendations: (i) postoperative cholecystectomy versus prophylactic CCY safety should be further explored; (ii) excess weight loss should be reported more consistently since findings are still not consensual regarding its lithogenic influence.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugerman HJ, Livingston EH, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547-59. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013. PubMed PMID: 15809466.

Jonas E, Marsk R, Rasmussen F, Freedman J. Incidence of postoperative gallstone disease after antiobesity surgery: population-based study from Sweden. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(1):54-8. Epub 20090504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2009.03.221. PubMed PMID: 19640806.

Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012;6(2):172-87. Epub 20120417. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172. PubMed PMID: 22570746; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3343155.

Chang J, Corcelles R, Boules M, Jamal MH, Schauer PR, Kroh MD. Predictive factors of biliary complications after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(9):1706-10. Epub 20151114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2015.11.004. PubMed PMID: 26948453.

Guzman HM, Sepulveda M, Rosso N, San Martin A, Guzman F, Guzman HC. Incidence and Risk Factors for Cholelithiasis After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2019;29(7):2110-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03760-4. PubMed PMID: 31001756.

Li VK, Pulido N, Fajnwaks P, Szomstein S, Rosenthal R, Martinez-Duartez P. Predictors of gallstone formation after bariatric surgery: a multivariate analysis of risk factors comparing gastric bypass, gastric banding, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(7):1640-4. Epub 20081205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-0204-6. PubMed PMID: 19057954.

Morais M, Faria G, Preto J, Costa-Maia J. Gallstones and bariatric surgery: to treat or not to treat? World journal of surgery. 2016;40(12):2904-10.

Warschkow R, Tarantino I, Ukegjini K, Beutner U, Güller U, Schmied BM, et al. Concomitant cholecystectomy during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese patients is not justified: a meta-analysis. Obesity surgery. 2013;23(3):397-407.

Sasaki A, Nakajima J, Nitta H, Obuchi T, Baba S, Wakabayashi G. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with a history of gastrectomy. Surg Today. 2008;38(9):790-4. Epub 20080828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-007-3726-y. PubMed PMID: 18751943.

Tustumi F, Bernardo WM, Santo MA, Cecconello I. Cholecystectomy in Patients Submitted to Bariatric Procedure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2018;28(10):3312-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3443-1. PubMed PMID: 30097898.

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors). Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895435609001802.

National Heart L, Institute B, Health NIo, Health UDo, Services H. Study quality assessment tools. Availabe online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health‐topics/study‐quality‐assessment‐tools (accessed on 1206). 2019.

Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ, Ades A. Evidence synthesis for decision making 3: heterogeneity—subgroups, meta-regression, bias, and bias-adjustment. Medical Decision Making. 2013;33(5):618-40.

Abu Abeid S, Szold A, Gavert N, Goldiner I, Grynberg E, Peretz H, et al. Apolipoprotein-E genotype and the risk of developing cholelithiasis following bariatric surgery: a clue to prevention of routine prophylactic cholecystectomy. Obes Surg. 2002;12(3):354-7. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089202321087850. PubMed PMID: 12087994.

Ahmed AR, O’Malley W, Johnson J, Boss T. Cholecystectomy during laparoscopic gastric bypass has no effect on duration of hospital stay. Obesity surgery. 2007;17(8):1075-9.

Aldriweesh MA, Aljahdali GL, Shafaay EA, Alangari DZ, Alhamied NA, Alradhi HA, et al. The Incidence and Risk Factors of Cholelithiasis Development After Bariatric Surgery in Saudi Arabia: A Two-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Surg. 2020;7:559064. Epub 20201022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2020.559064. PubMed PMID: 33195385; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7641899.

Alimoğulları M, Buluş H. Predictive factors of gallstone formation after sleeve gastrectomy: a multivariate analysis of risk factors. Surg Today. 2020;50:1002–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-01971-2.

Alsaif FA, Alabdullatif FS, Aldegaither MK, Alnaeem KA, Alzamil AF, Alabdulkarim NH, et al. Incidence of symptomatic cholelithiasis after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and its association with rapid weight loss. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(2):94-8. https://doi.org/10.4103/sjg.SJG_472_19. PubMed PMID: 32031160; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7279075.

Amstutz S, Michel JM, Kopp S, Egger B. Potential Benefits of Prophylactic Cholecystectomy in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Bypass Surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25(11):2054-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1650-6. PubMed PMID: 25804356.

Anveden A, Peltonen M, Naslund I, Torgerson J, Carlsson LMS. Long-term incidence of gallstone disease after bariatric surgery: results from the nonrandomized controlled Swedish Obese Subjects study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(10):1474-82. Epub 20200601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2020.05.025. PubMed PMID: 32654897.

Aridi HD, Sultanem S, Abtar H, Safadi BY, Fawal H, Alami RS. Management of gallbladder disease after sleeve gastrectomy in a selected Lebanese population. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2016;12(7):1300-4.

Brockmeyer JR, Grover BT, Kallies KJ, Kothari SN. Management of biliary symptoms after bariatric surgery. Am J Surg. 2015;210(6):1010-6; discussion 6-7. Epub 20150911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.003. PubMed PMID: 26454652.

Chen J-H, Tsai M-S, Chen C-Y, Lee H-M, Cheng C-F, Chiu Y-T, et al. Bariatric surgery did not increase the risk of gallstone disease in obese patients: a comprehensive cohort study. Obesity surgery. 2019;29(2):464-73.

Coşkun H, Hasbahçeci M, Bozkurt S, Çipe G, Malya FÜ, Memmi N, et al. Is concomitant cholecystectomy with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy safe? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25(6):624-7.

D'Hondt M, Sergeant G, Deylgat B, Devriendt D, Van Rooy F, Vansteenkiste F. Prophylactic cholecystectomy, a mandatory step in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(9):1532-6. Epub 20110713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1617-4. PubMed PMID: 21751078.

De Oliveira CIB, Chaim EA, Da Silva BB. Impact of rapid weight reduction on risk of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery. Obesity surgery. 2003;13(4):625-8.

El Hadidi A, Noaman N, Abdelhalim M, Taha A, Shetiwy M, Attia MS. Is concomitant cholecystectomy with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy mandatory? The Egyptian Journal of Surgery. 2019;38(3):418.

Hasan MY, Lomanto D, Loh LL, So JBY, Shabbir A. Gallstone Disease After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in an Asian Population-What Proportion of Gallstones Actually Becomes Symptomatic? Obes Surg. 2017;27(9):2419-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2657-y. PubMed PMID: 28401383.

Karadeniz M, Görgün M, Kara C. The evaluation of gallstone formation in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass due to morbid obesity. Turkish Journal of Surgery/Ulusal cerrahi dergisi. 2014;30(2):76.

Kiewiet RM, Durian MF, van Leersum M, Hesp FL, van Vliet AC. Gallstone formation after weight loss following gastric banding in morbidly obese Dutch patients. Obes Surg. 2006;16(5):592-6. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089206776945020. PubMed PMID: 16687027.

Kzilkaya M,Yilmaz S. The Fate of the Gallbladder in Patients Admitted to Bariatric Surgery. Haseki Tıp Bülteni. 2021; 59(1):80-84. https://doi.org/10.4274/haseki.galenos.2021.6716.

Lasnibat JP, Molina JC, Lanzarini E, Musleh M, von Jentschyk N, Valenzuela D, et al. Colelitiasis en pacientes obesos sometidos a cirugía bariátrica: estudio y seguimiento postoperatorio a 12 meses. Revista chilena de cirugía. 2017;69(1):49-52.

Manatsathit W, Leelasinjaroen P, Al-Hamid H, Szpunar S, Hawasli A. The incidence of cholelithiasis after sleeve gastrectomy and its association with weight loss: a two-centre retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Surgery. 2016;30:13-8.

Melmer A, Sturm W, Kuhnert B, Engl-Prosch J, Ress C, Tschoner A, et al. Incidence of Gallstone Formation and Cholecystectomy 10 Years After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25(7):1171-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1529-y. PubMed PMID: 25589017.

Moon RC, Teixeira AF, DuCoin C, Varnadore S, Jawad MA. Comparison of cholecystectomy cases after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(1):64-8. Epub 20130604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.04.019. PubMed PMID: 23932005.

Nagem R, Lazaro-da-Silva A. Cholecystolithiasis after gastric bypass: a clinical, biochemical, and ultrasonographic 3-year follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2012;22(10):1594-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0710-4. PubMed PMID: 22767176.

Nougou A, Suter M. Almost routine prophylactic cholecystectomy during laparoscopic gastric bypass is safe. Obesity surgery. 2008;18(5):535-9.

O'Brien PE, Dixon JB. A rational approach to cholelithiasis in bariatric surgery: its application to the laparoscopically placed adjustable gastric band. Arch Surg. 2003;138(8):908-12. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.138.8.908. PubMed PMID: 12912752.

Papavramidis S, Deligianidis N, Papavramidis T, Sapalidis K, Katsamakas M, Gamvros O. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy after bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(7):1061-4. Epub 20030428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-002-9169-z. PubMed PMID: 12712384.

Patel JA, Patel NA, Piper GL, Smith III DE, Malhotra G, Colella JJ. Perioperative management of cholelithiasis in patients presenting for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: have we reached a consensus? The American Surgeon. 2009;75(6):470-6.

Patel KR, White S, Tejirian T, Han SH, Russell D, Vira D, et al. Gallbladder management during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: routine preoperative screening for gallstones and postoperative prophylactic medical treatment are not necessary. The American Surgeon. 2006;72(10):857-61.

Pineda O, Maydon HG, Amado M, Sepulveda EM, Guilbert L, Espinosa O, et al. A Prospective Study of the Conservative Management of Asymptomatic Preoperative and Postoperative Gallbladder Disease in Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2017;27(1):148-53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2264-3. PubMed PMID: 27324135.

Plecka Ostlund M, Wenger U, Mattsson F, Ebrahim F, Botha A, Lagergren J. Population-based study of the need for cholecystectomy after obesity surgery. Br J Surg. 2012;99(6):864-9. Epub 20120307. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8701. PubMed PMID: 22407811.

Portenier DD, Grant JP, Blackwood HS, Pryor A, McMahon RL, DeMaria E. Expectant management of the asymptomatic gallbladder at Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2007;3(4):476-9.

Sakcak I, Avsar FM, Cosgun E, Yildiz BD. Management of concurrent cholelithiasis in gastric banding for morbid obesity. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(9):766-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283488adb. PubMed PMID: 21712718.

Santos BF, Spaniolas D, Trus T. Concurrent cholecystectomy at the time of laparoscopic gastric bypass does not increase short-term morbidity, mortality, or length of stay. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2014;219(4):e1-e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.07.392. PubMed PMID: WOS:000361111400004.

Sioka E, Zacharoulis D, Zachari E, Papamargaritis D, Pinaka O, Katsogridaki G, et al. Complicated gallstones after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. J Obes. 2014;2014:468203. Epub 20140703. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/468203. PubMed PMID: 25105023; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4106056.

Taha MIA, Freitas Jr WR, Puglia CR, Lacombe A, Malheiros CA. Fatores preditivos de colelitíase em obesos mórbidos após astroplastia em Y de Roux. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 2006;52:430-4.

Tarantino I, Warschkow R, Steffen T, Bisang P, Schultes B, Thurnheer M. Is routine cholecystectomy justified in severely obese patients undergoing a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure? A comparative cohort study. Obesity surgery. 2011;21(12):1870-8.

Tucker O, Fajnwaks P, Szomstein S, Rosenthal R. Is concomitant cholecystectomy necessary in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery? Surgical endoscopy. 2008;22(11):2450-4.

Wanjura V, Szabo E, Osterberg J, Ottosson J, Enochsson L, Sandblom G. Morbidity of cholecystectomy and gastric bypass in a national database. Br J Surg. 2018;105(1):121-7. Epub 20171018. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10666. PubMed PMID: 29044465.

Wood SG, Kumar SB, Dewey E, Lin MY, Carter JT. Safety of concomitant cholecystectomy with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: a MBSAQIP analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(6):864-70. Epub 20190320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2019.03.004. PubMed PMID: 31060907.

Zilberstein B, Pajecki D, Andrade CG, Eshkenazy R, De Brito ACG, Gallafrio ST. Simultaneous gastric banding and cholecystectomy in the treatment of morbid obesity: is it feasible? Obesity surgery. 2004;14(10):1331-4.

Li VK, Pulido N, Martinez-Suartez P, Fajnwaks P, Jin HY, Szomstein S, et al. Symptomatic gallstones after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(11):2488-92. Epub 20090404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0422-6. PubMed PMID: 19347402.

Bastouly M, Arasaki CH, Ferreira JB, Zanoto A, Borges FG, Del Grande JC. Early changes in postprandial gallbladder emptying in morbidly obese patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: correlation with the occurrence of biliary sludge and gallstones. Obes Surg. 2009;19(1):22-8. Epub 20080812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9648-y. PubMed PMID: 18696168.

Caruana JA, McCabe MN, Smith AD, Camara DS, Mercer MA, Gillespie JA. Incidence of symptomatic gallstones after gastric bypass: is prophylactic treatment really necessary? Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2005;1(6):564-7.

Coupaye M, Calabrese D, Sami O, Msika S, Ledoux S. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2017;13(4):681-5.

Dakour-Aridi HN, El-Rayess HM, Abou-Abbass H, Abu-Gheida I, Habib RH, Safadi BY. Safety of concomitant cholecystectomy at the time of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2017;13(6):934-41.

Dorman RB, Zhong W, Abraham AA, Ikramuddin S, Al-Refaie WB, Leslie DB, et al. Does concomitant cholecystectomy at time of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass impact adverse operative outcomes? Obesity surgery. 2013;23(11):1718-26.

Juo YY, Khrucharoen U, Chen Y, Sanaiha Y, Benharash P, Dutson E. Cost analysis and risk factors for interval cholecystectomy after bariatric surgery: a national study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):368-74. Epub 20171121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.015. PubMed PMID: 29519664.

Kim J-J, Schirmer B. Safety and efficacy of simultaneous cholecystectomy at Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2009;5(1):48-53.

Scott DJ, Villegas L, Sims TL, Hamilton EC, Provost DA, Jones DB. Intraoperative ultrasound and prophylactic ursodiol for gallstone prevention following laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(11):1796-802. Epub 20030910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-002-8930-7. PubMed PMID: 12958683.

Sucandy I, Abulfaraj M, Naglak M, Antanavicius G. Risk of Biliary Events After Selective Cholecystectomy During Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch. Obes Surg. 2016;26(3):531-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1786-4. PubMed PMID: 26156307.

Yang H, Petersen GM, Roth MP, Schoenfield LJ, Marks JW. Risk factors for gallstone formation during rapid loss of weight. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(6):912-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01300390. PubMed PMID: 1587196.

Veyrie N, Servajean S, Berger N, Loire P, Basdevant A, Bouillot J-L. Complications vésiculaires après chirurgie bariatrique. Gastroentérologie clinique et biologique. 2007;31(4):378-84.

Doulamis IP, Michalopoulos G, Boikou V, Schizas D, Spartalis E, Menenakos E, et al. Concomitant cholecystectomy during bariatric surgery: the jury is still out. The American Journal of Surgery. 2019;218(2):401-10.

Sneineh MA, Harel L, Elnasasra A, Razin H, Rotmensh A, Moscovici S, et al. Increased Incidence of Symptomatic Cholelithiasis After Bariatric Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass and Previous Bariatric Surgery: a Single Center Experience. Obes Surg. 2020;30(3):846-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04366-6. PubMed PMID: 31901127.

Al-Jiffry BO, Shaffer EA, Saccone GT, Downey P, Kow L, Toouli J. Changes in gallbladder motility and gallstone formation following laparoscopic gastric banding for morbid obesity. Canadian journal of gastroenterology. 2003;17(3):169-74.

Xia C, Wang M, Lv H, Li M, Jiang C, Liu Z, et al. The Safety and Necessity of Concomitant Cholecystectomy During Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Obesity: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2021;31(12):5418-26. Epub 20210926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05713-2. PubMed PMID: 34564789.

Yardimci S, Coskun M, Demircioglu S, Erdim A, Cingi A. Is concomitant cholecystectomy necessary for asymptomatic cholelithiasis during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy? Obesity Surgery. 2018;28(2):469-73.

Uy MC, Talingdan-Te MC, Espinosa WZ, Daez ML, Ong JP. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the prevention of gallstone formation after bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2008;18(12):1532-8. Epub 20080624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9587-7. PubMed PMID: 18574646.

Leyva-Alvizo A, Arredondo-Saldana G, Leal-Isla-Flores V, Romanelli J, Sudan R, Gibbs KE, et al. Systematic review of management of gallbladder disease in patients undergoing minimally invasive bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(1):158-64. Epub 20191031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2019.10.016. PubMed PMID: 31839526.

Acknowledegments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the Obesity Integrated Responsibility Unit (CRI-O) group members.

Data extracted from included studies, data used for all analyses, and any other materials used in the present systematic review and meta-analysis are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design. F. Amorim-Cruz, H. Santos-Sousa, M. Ribeiro, A. Costa-Pinho and B. Sousa-Pinto were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. F. Amorim-Cruz, H. Santos-Sousa and B. Sousa-Pinto were involved in the drafting of the article. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the article. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key points

• The risk of symptomatic GD after BS is not substantially high.

• Gallstone disease predictive factors after BS are not like those of the general population.

• Prophylactic cholecystectomy would have higher postoperative complications.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amorim-Cruz, F., Santos-Sousa, H., Ribeiro, M. et al. Risk and Prophylactic Management of Gallstone Disease in Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and A Bayesian meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 27, 433–448 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-022-05567-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-022-05567-8