Abstract

Introduction

The morbidity and mortality of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) have significantly decreased over the past decades to the point that they are no longer the sole indicators of quality and safety. In recent times, hospital readmission is increasingly used as a quality metric for surgical performance and has direct implications on health-care costs. We sought to delineate the natural history and predictive factors of readmissions after PD.

Methods

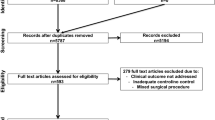

The clinicopathologic and long-term follow-up data of 1,173 consecutive patients who underwent PD between August 2002 and August 2012 at the Massachusetts General Hospital were reviewed. The NSQIP database was linked with our clinical database to supplement perioperative data. Readmissions unrelated to the index admission were omitted.

Results

We identified 173 (15 %) patients who required readmission after PD within the study period. The readmission rate was higher in the second half of the decade when compared to the first half (18.6 vs 12.3 %, p = 0.003), despite a stable 7-day median length of stay. Readmitted patients were analyzed against those without readmissions after PD. The demographics and tumor pathology of both groups did not differ significantly. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, pancreatic fistula (18.5 vs 11.3 %, OR 1.86, p = 0.004), multivisceral resection at time of PD (3.5 vs 0.6 %, OR 4.02, p = 0.02), length of initial hospital stay >7 days (59.5 vs 42.5 %, OR 1.57, p = 0.01), and ICU admissions (11.6 vs 3.4 %, OR 2.90, p = 0.0005) were independently associated with readmissions. There were no postoperative biochemical variables that were predictive of readmissions. Fifty percent (n = 87) of the readmissions occurred within 7 days from initial operative discharge. The reasons for immediate (≤7 days) and nonimmediate (>7 days) readmissions differed; ileus, delayed gastric emptying, and pneumonia were more common in early readmissions, whereas wound infection, failure to thrive, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage were associated with late readmissions. The incidences of readmissions due to pancreatic fistulas and intra-abdominal abscesses were equally distributed between both time frames. The frequency of readmission after PD is 15 % and has been on the uptrend over the last decade.

Conclusion

The complexity of initial resection and pancreatic fistula were independently associated with hospital readmissions after PD. Further efforts should be centered on preventing early readmissions, which constitute half of all readmissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic resection in the 1990s. Archives of Surgery. 1995;130(3):295–9; discussion 9–300. Epub 1995/03/01.

Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;125(3):250–6. Epub 1999/03/17.

Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2006;10(9):1199–210; discussion 210–1. Epub 2006/11/23.

Fernandez-del Castillo C, Morales-Oyarvide V, McGrath D, Wargo JA, Ferrone CR, Thayer SP, et al. Evolution of the Whipple procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgery. 2012;152(3 Suppl 1):S56-63. Epub 2012/07/10.

Schneider EB, Hyder O, Brooke BS, Efron J, Cameron JL, Edil BH, et al. Patient readmission and mortality after colorectal surgery for colon cancer: impact of length of stay relative to other clinical factors. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2012;214(4):390–8; discussion 8–9. Epub 2012/02/01.

Greenblatt DY, Weber SM, O'Connor ES, LoConte NK, Liou JI, Smith MA. Readmission after colectomy for cancer predicts one-year mortality. Annals of Surgery. 2010;251(4):659–69. Epub 2010/03/13.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(14):1418–28. Epub 2009/04/03.

Yermilov I, Bentrem D, Sekeris E, Jain S, Maggard MA, Ko CY, et al. Readmissions following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreas cancer: a population-based appraisal. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009;16(3):554–61. Epub 2008/11/13.

Reddy DM, Townsend CM, Jr., Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS, Riall TS. Readmission after pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer in Medicare patients. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2009;13(11):1963–74; discussion 74–5. Epub 2009/09/18.

Kastenberg ZJ, Morton JM, Visser BC, Norton JA, Poultsides GA. Hospital readmission after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: an emerging quality metric? HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2013;15(2):142–8. Epub 2013/01/10.

Gawlas I, Sethi M, Winner M, Epelboym I, Lee JL, Schrope BA, et al. Readmission After Pancreatic Resection is not an Appropriate Measure of Quality. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013. 20:1781–7

Ahmad SA, Edwards MJ, Sutton JM, Grewal SS, Hanseman DJ, Maithel SK, et al. Factors influencing readmission after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a multi-institutional study of 1302 patients. Annals of Surgery. 2012;256(3):529–37. Epub 2012/08/08.

Grewal SS, McClaine RJ, Schmulewitz N, Alzahrani MA, Hanseman DJ, Sussman JJ, et al. Factors associated with recidivism following pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2011;13(12):869–75. Epub 2011/11/16.

Kent TS, Sachs TE, Callery MP, Vollmer CM, Jr. Readmission after major pancreatic resection: a necessary evil? Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011;213(4):515–23. Epub 2011/08/16.

Emick DM, Riall TS, Cameron JL, Winter JM, Lillemoe KD, Coleman J, et al. Hospital readmission after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2006;10(9):1243–52; discussion 52–3. Epub 2006/11/23.

Warshaw AL, Thayer SP. Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2004;8(6):733–41. Epub 2004/09/11.

Veillette G, Dominguez I, Ferrone C, Thayer SP, McGrath D, Warshaw AL, et al. Implications and management of pancreatic fistulas following pancreaticoduodenectomy: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Archives of Surgery. 2008;143(5):476–81. Epub 2008/05/21.

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138(1):8–13. Epub 2005/07/09.

Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142(5):761–8. Epub 2007/11/06.

van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, Busch OR, de Wit LT, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Readmissions after pancreatoduodenectomy. The British Journal of Surgery. 2001;88(11):1467–71. Epub 2001/10/31.

Kent TS, Sachs TE, Callery MP, Vollmer CM, Jr. The burden of infection for elective pancreatic resections. Surgery. 2013;153(1):86–94. Epub 2012/06/16.

Warschkow R, Ukegjini K, Tarantino I, Steffen T, Muller SA, Schmied BM, et al. Diagnostic study and meta-analysis of C-reactive protein as a predictor of postoperative inflammatory complications after pancreatic surgery. Journal of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Sciences. 2012;19(4):492–500. Epub 2011/11/01.

Stojadinovic A, Brooks A, Hoos A, Jaques DP, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. An evidence-based approach to the surgical management of resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2003;196(6):954–64. Epub 2003/06/06.

Schulick RD. Complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: intraabdominal abscess. Journal of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Surgery. 2008;15(3):252–6. Epub 2008/06/07.

Rosemurgy AS, Luberice K, Paul H, Co F, Vice M, Toomey P, et al. Readmissions after pancreaticoduodenectomy: efforts need to focus on patient expectations and nonhospital medical care. The American Surgeon. 2012;78(8):837–43. Epub 2012/08/04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Discussant

Dr. Charles Vollmer, Jr. (Philadelphia, PA): Readmissions in GI surgery is the “it” topic today, as evidenced by three papers at the Pancreas Club, as well as two separate offerings at this conference, all on the heels of two major presentations at the American Surgical over the last 2 years. Of all subsets of GI surgery, pancreatectomy poses the biggest threat for readmission due to its inherent features. The Massachusetts General Hospital group once again sets a benchmark for care as they describe one of the lowest contemporary readmission rates for pancreatectomy.

It certainly feels as if readmission is being thrust upon us as a quality metric. Unfortunately, like most of these current quality indicators we are increasingly being held accountable for, policy wonks have “leaped before they looked,” and I am afraid that is the direction this too is taking. Practically, we are not even close to understanding the mechanics of this metric. First and foremost, we do not really know what the “norm” is for this, nor the variance from it. Secondly, if there is variance, risk adjustment processes are necessary to interpret the ultimate outcomes. While this paper presents some basic preop comorbidities, age, and ASA class, none of them were predictive with the exception of preop nutritional status. We desperately need, and await, better sophistication in describing preop acuity for those undergoing pancreatectomy, if not all surgical patients. Quite simply, ASA status is not good enough.

Perhaps the most important data comes from Fig. 2 in the paper where the inverse relationship between duration of stay and readmissions is depicted. These competing entities cannot each be optimized. So, Dr. Fong, I ask you, which is the more realistic quality indicator for us? If I interpret it correctly, the “sweet spot,” or intersect of the slopes, occurs around day 10–11. In these times of pathways, and with a push to decrease LOS down to 6–7 days, is cost the answer to the puzzle? What costs more, a readmission, or 3–4 days more in the hospital managing complications?

Back to the variance issue. Your data clearly show that the surgeon is not the driver—at least when judged by volume. If there is no variance between the surgeons, there are no outliers to be either reprimanded or emulated. So, if not us, then who should be accountable for this if it becomes a quality indicator?

Finally, I applaud the authors for this comment from the manuscript, “Readmissions are likely artifacts of variation in illness severity rather than an indicator of poor patient care.” I also appreciate the author's reference to a phrase we coined in our paper on this topic where we questioned if readmissions following pancreatectomy are a “necessary evil.” I have since had second thoughts on this, as I am not convinced it is an “evil” at all. We need to be vociferous about this in the face of the external forces who are acting on our behalf without appreciating both our travails and our patients' misfortunes. The implication is that readmissions are the result of poor judgment and/or shoddy work by the practitioner. This paper should help set that misconception straight.

Closing Discussant

Dr. Zhi Ven Fong: Thank you for your insightful comments, Dr. Vollmer. Indeed, now that monetary penalties for excessive readmission rate among hospitals are more of a reality than mere proposals, the metric has garnered increasing interest among surgeons with fears that such policies could include surgical patients. This transference of policy to patients undergoing a complex procedure such as a pancreaticoduodenectomy, however, is not appropriate. Based on our data, readmissions after a Whipple were not a result of subpar quality of care, but rather “rescue” readmissions that managed complications that manifested late in the postoperative course and are not captured by the index admission.

In addressing your first question, we do not have data on the cost of a readmission or retaining patients for an additional 3–4 days to manage late complications. We do, however, have data showing that less than 15 % of our total cohort of patients over 10 years would have required those extra few days to prevent their readmission. Hence, we think it would be counterintuitive to be subjecting 85 % of the discharge-ready patients to an additional 3–4 days of hospital stay to avoid those readmissions. Rather, we should use readmission as a safety mechanism (as opposed to the initial coined term, necessary evil) to allow us to safely discharge patients as early as critical pathways dictate.

In regard to your second question, we do not think that anyone should be accountable to these readmissions. To date, there is no evidence-based practice that prevents any of the main reasons for readmission after a pancreaticoduodenectomy, namely intra-abdominal abscess, delayed gastric emptying, and ileus. It will be, however, our fault if we fail to recognize the need for a readmission in this vulnerable cohort of patients (fivefold increase in mortality) and shut the door on them because of pressure from insurance companies and reimbursement policies. We reiterate your comment that the concept that readmissions after a Whipple procedure are an indicator of substandard care provided should be stamped out. Rather, they are essential in this current era where physicians are expected to do more with less, particularly after a complex procedure such as a pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fong, Z.V., Ferrone, C.R., Thayer, S.P. et al. Understanding Hospital Readmissions After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Can We Prevent Them?. J Gastrointest Surg 18, 137–145 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2336-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2336-9