Abstract

Background

Emergency treatment of bleeding esophageal varices (BEV) in cirrhotic patients is of prime importance because of the high mortality rate surrounding the episode of acute bleeding. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of randomized controlled trials of emergency surgical therapy and no reports of the costs of any of the widely used forms of emergency treatment. The important issue of direct costs of care was examined in a randomized controlled trial that compared endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) to emergency portacaval shunt (EPCS).

Methods

Two hundred eleven unselected consecutive patients with ultimately biopsy-proven cirrhosis and endoscopically proven acute BEV were randomized to EST (n = 106) or EPCS (n = 105). Diagnostic workup was completed, and EST or EPCS was initiated within 8 h. Criteria for failure of EST or EPCS were clearly defined, and crossover rescue treatment was applied, when primary therapy failed. Ninety-six percent of patients underwent more than 10 years follow-up, or until death. Complete charges for all aspects of care were obtained continuously for more than 10 years.

Results

Direct charges for all aspects of care were significantly lower in patients treated by EPCS than in patients treated by emergency EST followed by long-term repetitive sclerotherapy. Charges per patient, per year of treatment, and per year in each child’s risk class were significantly lower in patients randomized to EPCS. Charges in patients who failed endoscopic sclerotherapy and underwent a rescue portacaval shunt were significantly higher than the charges in both the unshunted sclerotherapy patients and the patients randomized to EPCS. This result was particularly noteworthy given the widespread practice of using surgical portacaval shunt as rescue treatment only when all other forms of therapy have failed.

Conclusions

In this randomized controlled trial of emergency treatment of acute BEV, EPCS was significantly superior to EST with regard to direct costs of care as reflected in charges for care as well as in survival rate, control of bleeding, and incidence of portal-systemic encephalopathy. These results provide support for the use of EPCS as a first line of emergency treatment of BEV in cirrhosis (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00690027).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extensive data reported during the past 60 years have provided clear evidence that bleeding esophageal varices (BEV) is a common and highly lethal complication of cirrhosis of the liver.1 The period surrounding the episode of acute bleeding has been reported to account for much of the mortality rate associated with BEV.1 A number of modalities of emergency treatment of BEV are in use including pharmacologic measures, endoscopic therapy, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and surgical portal decompression. There is no agreement which of these modalities is most effective, but there is general agreement that emergency treatment of BEV is of prime importance. Nevertheless, few randomized controlled trials of the various modalities of emergency treatment have been reported. In particular, no randomized trials involving emergency surgical therapy have been described. Moreover, little is known about the costs associated with emergency treatment of BEV, an important measure of the effectiveness of therapy.

From April 8, 1988, to December 31, 2005, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 211 unselected consecutive patients with cirrhosis and acute BEV in whom emergency and long-term repetitive endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) was compared with emergency direct portacaval shunt (EPCS). The trial was a community-wide endeavor and was known as the San Diego Bleeding Esophageal Varices Study. In two recent publications, we described the study in detail and reported the outcomes first with regard to control of bleeding and survival,2 and second with regard to development of portal-systemic encephalopathy (PSE).3 In a third publication, we compared EPCS to rescue PCS following failed EST.4 This report focuses on direct costs of care.

Patients and Methods

Design of Randomized Controlled Trial

Our two recent publications2,3 described our RCT and provided full information on the protocols and methods. These include (1) design of study; (2) patient eligibility; (3) definitions (BEV, unselected patients (“all comers”), emergency EST, long-term EST, EPCS, failure of emergency primary therapy, failure of long-term therapy, rescue therapy, informed consent); (4) randomization; (5) diagnostic workup; (6) quantitative child’s classification; (7) initial emergency therapy during workup; (8) endoscopic sclerotherapy; (9) emergency portacaval shunt; (10) posttreatment therapy; (11) lifelong follow-up; (12) quantitation of PSE; (13) data collection. The study protocol and consent forms were approved before the start of the study and at regular intervals thereafter by the UCSD Human Subjects Committee (Institutional Review Board). Figure 1 is a Consort Flow Diagram that shows the overall design and conduct of the RCT.5, 6

Direct Costs of Care

The EST and EPCS groups were compared with regard to direct costs of care. Complete UCSD charges were obtained for every patient entered in the RCT. In addition, all referring hospitals and referring physicians signed agreements to provide complete records of charges as they occurred. Prior to initiation of the study, UCSD Medical Center agreed to promptly provide copies of all hospital and outpatient charges on all patients at the time when the patients and insurance carriers were billed. Similarly, the UCSD Medical Group, which does the professional fee billing for all physicians who care for patients at UCSD Medical Center, agreed to promptly provide copies of all professional fee bills. Direct cost of care data were obtained from April 8, 1988 to November 11, 1999, after which there were too few survivors of EST to permit a valid comparison of direct cost data in the two study groups. In the final analysis, cost of care data from referring hospitals and non-UCSD physicians were not obtained for 30 of the 627 hospital readmissions (5%) and for 203 of the 4,757 readmission days (4%), equally divided between the EST and EPCS groups. This small deficiency in data collection had no influence on the overall results of the analysis.

Sources of healthcare funding or non-funding of all patients were identified at the time of entry in the study and continuously thereafter. Our analysis of direct costs of care has been accepted for oral presentation at a national meeting.

Statistical Analysis

The survival times were computed using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared between arms using the log-rank test. Quality of life indices were compared between arms using Fisher’s exact test (for categorical outcomes) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (WRT; for continuous outcomes). For the charges for care in each category and for each treatment arm, the mean, standard deviation, and range (minimum–maximum) were computed. The comparison between arms used the nonparametric WRT. The charges per day for index admission were computed by dividing the index admission charges by the number of days of hospitalization. The charges per year for post-index admission and total were obtained by dividing the charges by the number of years of follow-up. The comparison between arms used the WRT. The sources of healthcare funding were compared between arms using Fisher’s exact test. At the beginning of the study, it was decided in advance not to perform an interim statistical analysis of the data, so as not to diminish the power of the final analysis.

Results

Overall Outcome Data of EST versus EPCS

Our recent publications described the clinical characteristics of the 211 patients, findings on liver biopsy and initial upper endoscopy, results of laboratory blood tests, data on rapidity of therapy, data on control of bleeding, operative and endoscopic data, data on PSE, and data on survival.2,3 On entry in the RCT the two groups were similar in every important characteristics of cirrhosis and BEV. Histologic proof of cirrhosis was obtained in all patients. Mean and median times from onset of bleeding to entry in the San Diego BEV Study were less than 20 h in both groups of patients, and from onset of bleeding to start of EST or EPCS were less than 24 h. Excluding indeterminate deaths within 14 days unrelated to bleeding, EST achieved permanent long-term control of bleeding in only 20% of patients. In contrast, EPCS promptly and permanently controlled bleeding in every patient. Patients in the EST group required significantly more units of PRBC than those in the EPCS group because of continued or recurrent BEV. Survival rates at all time intervals and in all Child’s classes were significantly higher after EPCS than after EST (p < 0.001). Moreover, EPCS resulted in substantial long-term survival of patients in child’s risk class C who had the most advanced cirrhosis of the liver. The incidence of recurrent PSE following EST was 35%, which was more than twice the 15% incidence following EPCS (p < 0.001). EST patients had a total of 146 PSE-related hospital admissions, compared with EPCS patients who had 87 such hospital admissions (p = 0.003). Recurrent UGI bleeding was a major causative factor of PSE in almost one half of the EST patients.

Direct Costs of Care

Table 1 summarizes the funding sources for all patients in the San Diego BEV Study. Medi-Cal, which in California is the form of Medicaid for low-income individuals, was the most frequent third-party carrier, accounting for 44% of third-party insurance coverage. A combination of Medi-Cal and Medicare provided healthcare insurance for 16% of patients, mainly those whose income was low and who were age 62 years or older, or had been declared permanently disabled. Patients whose income was below the poverty line and had no other healthcare insurance received coverage in 11% of the cases from San Diego County Medical Services. Fourteen percent of the patients had no healthcare insurance and 8% had private insurance. There were no significant differences in the funding sources of the two treatment groups. It is important to recognize that both the charges and actual costs of care were unrelated to the type of healthcare insurance or non-insurance held by each patient. For example, all EPCS patients received identical charges for a portacaval shunt unrelated to healthcare insurance or non-insurance. Similarly in the EST group the standard charges for a session of endoscopic sclerotherapy were not affected by a patient’s health insurance or non-insurance.

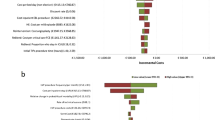

Table 2 and Fig. 2 show the charges for hospitalization and outpatient care in thousands of US dollars in the EST and EPCS treatment groups. As expected, the charges for all aspects of the index admission in patients who underwent EPCS were significantly greater than the charges for initial EST (p < 0.001). However, these charges were offset by significantly greater charges for post-index care in the EST group, in large measure because of recurrent BEV and the need for repeated readmissions to the hospital. In the final analysis, the total post-index charges were significantly greater in patients who were treated by EST compared to those who underwent EPCS (p < 0.001), and the total overall charges for emergency and long-term care required over a number of years were greater in patients who received emergency followed by long-term repetitive EST, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). Note however that the charges in the EPCS group were spread over a significantly longer period of time.

Table 3 and Fig. 2 show the important relationship between charges and days or years of required care. When related to length of survival and, therefore, days or years during which care was required, EPCS was significantly less expensive than EST in every aspect of care except for the index admission. Charges for post-index care per year in the EST and EPCS groups, respectively, were a mean $108,500 versus $25,100 (p < 0.001). Total overall charges for care of patients who entered the RCT were a mean $168,100 per year in the EST group, versus $39,400 per year in the EPCS group (p < 0.001).

Table 4 shows the charges according to Child’s risk classes assigned at the index admission. Total overall charges per patient were lower in the EPCS group, but the differences from the EST group were not significant except in Child’s class C. However, when charges were related to the more meaningful index of years of required treatment, mean total charges per year were significantly lower in patients randomized to EPCS than in those randomized to EST in all Child’s classes (p = 0.004 to <0.001). Since the EPCS patients lived much longer than the EST patients, the direct costs were spread over significantly more years and, therefore, the direct cost per year were much lower.

Table 5 and Fig. 2 compare the charges made to the 50 patients who failed EST and then underwent a rescue PCS, with the charges made to EST patients who did not have a rescue PCS and, additionally, with the charges made to patients in the EPCS group. Compared to EST patients who did not undergo a rescue PCS, mean total charges in patients who needed a rescue PCS were significantly higher per patient (p < 0.001) and per year (p = 0.02). Moreover, rescue PCS in the EST group was significantly more costly than EPCS per patient (p < 0.001) and per year (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In the San Diego BEV Study, we did not determine actual costs of care but used charges as an indicator of costs. After meetings with hospital administrations at UCSD Medical Center and the referring hospitals, it was made clear that obtaining actual cost data over the long follow-up period would not be possible. It was recognized that, as Finkler has pointed out, “on average charges must exceed costs because of the need for expansion and replacement of equipment and facilities,...to cover care to the indigent and courtesy care; costs of community service; and items disallowed by Blue Cross, Medicare, and Medicaid”.7 However, the purpose of our RCT was not so much to determine the true costs of emergency treatment but to compare EST versus EPCS. In that comparison, use of charge data was valid and meaningful. Patients in both groups received identical charges for all given items of care such as room rate, ICU rate, laboratory tests, endoscopy, and so on.

Another aspect of the cost of care which we did not measure was in the important category of indirect costs due to mortality and morbidity. These consist mainly of loss of earnings due to premature death and loss of earnings due to days lost from work, including days lost from full-time housekeeping for women. Indirect costs represent a substantial fraction of the costs of illness and can be measured by using life tables and data produced by the U.S. Bureau of the Census and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics as we have done in the past.8,9 Because EST, compared to EPCS in our RCT, had a significantly lower survival rate, shorter length of survival, and poorer quality of life due to recurrent BEV, recurrent PSE, and the need for repeated hospitalization, there can be no doubt that indirect costs of care were substantially higher in patients treated by EST than in those who underwent EPCS.

Only four studies of the presumed direct costs of emergency treatment of BEV have been reported, all of them involving small numbers of selected patients who underwent short follow-up. None of the studies determined the actual costs of care attributable to each individual patient. In 1984 and 1987, Cello and associates reported the results of a short-term RCT of emergency treatment of BEV conducted at a county general hospital.10,11 EST (n = 32) was compared with EPCS (n = 32) in highly selected patients with what they defined as Child’s class C cirrhosis. We have commented previously on this trial.2,3,12 Almost half of the patients died during the index hospitalization. Charges for healthcare were used as a surrogate for costs, and details for obtaining charge data were sketchy. Cello and associates reported that healthcare charges were similar in the EST and EPCS treatment groups.

In 1997, Cello and associates reported the results of a short-term RCT of emergency treatment of BEV in which EST (n = 25) was compared to TIPS (n = 24) in highly selected patients admitted to three hospitals, namely, a county general hospital, a veterans administration hospital, and a university teaching hospital.13 Follow-up information was obtained through face-to-face interviews, telephone interviews, or retrospective chart reviews. The costs of healthcare were determined but, considering the mode of follow-up, the data were incomplete. Moreover, the three hospitals differed in the assessment of hospital costs and professional fees, if any. The authors concluded that healthcare costs did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups.

In 1997 and again in 2003, Rosemurgy and colleagues reported the results of a RCT in which TIPS and H-graft portacaval shunt were compared in selected patients, most of whom were treated electively.14,15 In the 1997 report only eight patients underwent emergency therapy and in the 2003 report, which was restricted to patients in Child’s class C, only 13 patients were randomized to emergency care. Charges were used as a proxy for costs and a number of significant charges were excluded from the analysis. The authors concluded in both reports that there was no significant difference in charges for care between the two forms of treatment.

In 1999, Gralnek and colleagues reported the economic impact of endoscopic therapy of BEV in a RCT that compared EST versus endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) in selected patients who had only 1 year of follow-up.16 Only 21 patients in the study underwent emergency treatment, and three of these were lost to follow-up, leaving only 16 patients for analysis of the direct costs of emergency care. The patients were treated at a veterans hospital and a university teaching hospital, but the distribution of patients among these two facilities in which the costs of care were undoubtedly different, was not provided. Direct costs for all 16 patients were estimated from the “UCLA estimated institutional combined fixed and variable costs for each of the services or procedures adjusted to the 1995–96 rate.” Professional fee reimbursement was estimated using the 1996 AMA CPT codes and Medicare fee schedule. The actual costs engendered by individual patients were not determined. The authors concluded that median total direct costs and resource utilization were similar between EST and EVL.

At least 15 studies have been reported in which hypothetical models have been used to estimate cost of care of elective treatment aimed at primary prevention or secondary prophylaxis of BEV. Several recent publications have summarized these hypothetical studies.17–19 None of these studies have included emergency treatment or therapy by surgery or TIPS. The Markov model and an event simulation model have been used most widely to calculate costs of healthcare.20 The validity of these studies as a means of determining costs of healthcare is questionable because the calculations are based on a number of assumptions extracted from selected studies in the literature performed by other workers. Conclusions are the result of calculations, not personal observations, and are dependent on the accuracy of the reported observations of others.

There has been one recent RCT conducted by Henderson and colleagues that compared TIPS and distal splenorenal shunt and included cost of care calculations.21,22 The RCT involved 140 highly selected patients with well-compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh score of nine or less) who were admitted to five centers that were geographically distant from each other. The patients underwent TIPS or distal splenorenal shunt aimed at preventing variceal rebleeding. Nine hundred nine patients (85%) were excluded from the RCT and 33 refused to participate. Actual costs of care, or charges, or reimbursements were not determined. Cost analysis used diagnosis-related groups (DRG)-based costs for inpatient events and current processing terminology procedures (CPT)-based costs for outpatient events. National Medicare reimbursements from year 2003 were used for each DRG, inflated to year 2004 costs using the medical care inflation index. It was noted that a specific DRG for TIPS did not exist and had to be estimated based on Cleveland Clinic data applied to all five centers. Clearly, all costs of care were not included in the calculations. The authors concluded that there was no overall significant difference in the cost of managing these selected good-risk patients with either TIPS or distal splenorenal shunt.

The results of our RCT of emergency treatment of acute BEV followed by 9.4 to 10 years or more of follow-up indicate that direct costs of care as reflected by charges for all aspects of care were significantly lower in patients treated by EPCS than in those treated by EST. Overall charges per patient, charges per year of treatment, and charges per year in each Child’s risk class were significantly lower in patients with BEV randomized to EPCS than in patients randomized to emergency followed by long-term repetitive EST.

Of particular note were the charges in patients who failed EST and underwent a rescue PCS. Charges for such patients were significantly higher than the charges required by EST patients who did not have a rescue shunt as well as by the patients who underwent EPCS. This finding is noteworthy because the main use of surgical shunts in recent years in the USA and abroad has been as elective rescue treatment for failure of endoscopic therapy and other forms of treatment of esophageal varices. Our study indicates that such use of surgical shunts is not only substantially less effective than EPCS, but also is much more costly.

The reasons why EPCS was less costly than EST are very likely a consequence of differences in effectiveness of emergency treatment of BEV. The most important determinants of effectiveness of therapy are survival rate, control of bleeding, and incidence of recurrent PSE. As we have observed in our recent reports, compared to EST, EPCS produced a significantly greater survival rate, was much more effective in controlling bleeding, and was followed by less than one half the incidence of PSE.

The effects of EPCS and, therefore, the significantly lower charges for care, were the result of several critical aspects of care in our RCT: (1) simplification of the diagnostic workup so that emergency diagnosis was accomplished entirely at the bedside in a mean 4.4 h; (2) development of an organized system of pre- and post-therapy care; (3) a rigorous, lifelong program of follow-up with intensification of efforts to obtain dietary protein control and abstinence from alcohol; and (4) permanent (99%) long-term patency of the portacaval shunt.

As a final note, comment is warranted regarding the use of EST rather than EVL in this RCT, and the absence of TIPS. Our use of EST has received strong support from studies published in 2003, 2005 and 2006 that have questioned replacement of EST by EVL.23–26 We discussed this issue and the justification for our use of EST in our recent publications.2,4 It is noteworthy that currently, in our four-county community of 8.5 million people, gastroenterologists with whom we have had regular and frequent contact use EST more frequently than EVL. At the time when EVL was introduced at our institution we were well into our RCT and made the decision not to change from EST to EVL.

With regard to TIPS, which was popularized long after our RCT was initiated, it has become the most widely used procedure of choice when it is believed that portal decompression is needed. However, as we have pointed out previously, TIPS has a high rate of stenosis and occlusion, a resultant high incidence of PSE, and limited durability. The TIPS occlusion rate has been reduced by the recent introduction of the polytetrafluorethylene-coated stent, but the rates of occlusion and PSE are still much higher than the incidences of these serious complications following portacaval shunt in all of our studies. Recently, we completed a RCT comparing TIPS and EPCS and are in the process of analyzing the data for publication.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this RCT of emergency treatment of acute BEV in 211 unselected, consecutive patients with cirrhosis of all grades of severity, EPCS resulted in significantly lower charges for all aspects of care, even when failure of EST to control bleeding was treated by rescue PCS as salvage therapy. Charges for EPCS were substantially lower overall, as well as in relation to days or years of survival, and in each Child’s class. While charges are not identical to actual costs, and indirect costs were not determined, it is reasonable to conclude that the actual costs of EPCS, both direct and indirect, were significantly lower than the costs of EST. When added to the other demonstrated benefits of EPCS, specifically a higher and longer survival rate, markedly better control of bleeding, and significantly lower incidence of recurrent PSE, the results of our analysis of healthcare charges provide support for the use of EPCS as a first line of emergency treatment of BEV. Moreover, the results of this RCT raise questions about the widespread practice of using surgical portal-systemic shunt mainly or only as salvage therapy for failure of other modalities of therapy.

Abbreviations

- BEV:

-

Bleeding esophageal varices

- TIPS:

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

- EST:

-

Endoscopic sclerotherapy

- EPCS:

-

Emergency portacaval shunt

- PCS:

-

Portacaval shunt

- UGI:

-

Upper gastrointestinal

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PRBC:

-

Packed red blood cells

- PSE:

-

Portal-systemic encephalopathy

- EVL:

-

Endoscopic variceal ligation

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Orloff MJ, Portal hypertension and portacaval shunt. In: Surgical Research, W. Souba, D. Wilmore, eds., Harcourt Brace, San Diego, 2001, pp. 637–701.

Orloff MJ, Isenberg JI, Wheeler HO, Haynes KS, Jinich-Brook H, Rapier R, Vaida F, Hye RJ. Randomized trial of emergency endoscopic sclerotherapy versus emergency portacaval shunt for acutely bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis. J Am Coll Surg 2009; 209:25–45.

Orloff MJ, Isenberg JI, Wheeler HO, Haynes KS, Jinich-Brook H, Rapier R, Vaida F, Hye RJ. Portal-systemic encephalopathy in a randomized controlled trial of endoscopic sclerotherapy versus emergency portacaval shunt treatment of acutely bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis. Ann Surg 2009; 250:598–610.

Orloff MJ, Isenberg JI, Wheeler HO, Haynes KS, Jinich-Brook H, Rapier R, Vaida F, Hye RJ. Emergency portacaval shunt versus rescue portacaval shunt in a randomized controlled trial of emergency treatment of acutely bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis—Part 3. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; in press.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001; 285:1987–1991.

Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:663–694.

Finkler SA. The distinction between costs and charges. Ann Intern Med 1982; 96:102–109.

Orloff MJ, Ellwein LB, Folkman MJ, Kirklin JW, Mankin HJ, Najarian JS, Reemtsma K, Shires GT. Contributions of surgical research to health care. In: Study on Surgical Services for the United States, G Zuidema, ed., Lewis Advertising Co., Baltimore, 1975, 153–184.

Orloff MJ. Contributions of research in surgical technology to health care. In: Technology and the Quality of Health Care, R.H. Egdahl and P.M. Garman, eds., Aspens Systems Corp., Rockville, MD, 1978, 71–103

Cello P, Grendell JH, Crass RA, Trunkey DD, Cobb EE, Heilbron DC. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus portacaval shunt in patients with severe cirrhosis and variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 1984; 311:1589–94.

Cello JP, Grendell JH, Crass RA, Weber TE, Trunkey DD. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus portacaval shunt in patients with severe cirrhosis and acute variceal hemorrhage. Long-term follow-up. N Engl J Med 1987; 316:11–15.

Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Orloff SL, Rambotti M, Girard B. Three decades of experience with emergency portacaval shunt for acutely bleeding esophageal varices in 400 unselected patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 180:257–272.

Cello JP, Ring EJ, Olcott EW, Koch J, Gordon R, Sandhu J, Morgan DR, Ostroff JW, Rockey DC, Bacchetti P, LaBerge J, Lake JR, Somberg K, Doherty C, Davila M, McQuaid K, Wall SD. Endoscopic sclerotherapy compared with percutaneous transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt after initial sclerotherapy in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126:858–865.

Rosemurgy AS II, Bloomston M, Zervox EE, Goode SE, Pencev D, Zweibel B, Black TJ.. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus H-graft portacaval shunt in the management of bleeding varices: a cost-benefit analysis. Surgery 1997; 122(4):794–799.

Rosemurgy AS, Zervos EE, Bloomston M, Durkin AJ, Clark WC, Goff S. Post-shunt resource consumption favors small-diameter prosthetic H-graft portacaval shunt over TIPS for patients with poor hepatic reserve. Ann Surg 2003; 237(6):820–825.

Gralnek IM, Jensen DM, Kovacs TO, Jutabha R, Machicado GA, Gornbein J, King J, Cheng S, Jensen ME. The economic impact of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: cost-effectiveness implications of endoscopic therapy. Hepatology 1999; 29:44–50.

Talwalker JA. Cost effectivenss of treating esophageal varices. Clin Liver Dis 2006; 10:679–689.

Plevris JN, Haynes PC. Treating bleeding oesophageal varices with vasoactive agents: good value for money? Curr Med Res Opin 2007; 23(7):1745–47.

Imperiale TF, Klein RW, Chalasani N. Cost-effectiveness analysis of variceal ligation vs. beta-blockers for primary prevention of variceal bleeding. Hepatology 2007; 45:870–878.

Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision-making: a practical guide. Med Decision Making 1993; 13:322–338.

Henderson JM, Boyer TD, Kutner MH, Galloway JR, Rikkers LF, Jeffers LJ, Abu-Elmagd K, Connor J, DIVERT Study Group. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:1643–51.

Boyer TD, Henderson JM, Heerey AM, arrigain S, Konig V, Connor J, Abu-Elmagd K, Galloway J, Rikkers LF, Jeffers L, DIVERT Study Group. Cost of preventing variceal rebleeding with transjugular intrahepatic portal systemic shunt and distal splenorenal shunt. J Hepatol 2008; 48:407–414.

Krige JE, Shaw JM, Bornman PC. The evolving role of endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices. Wld J Surg 2005; 29:966–973.

Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Peura D, Johnson D, Lanza F, Foutch PG, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR. An assessment of the management of acute bleeding varices: a multicenter prospective member-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:2424–2434.

Gralnek IM, Jensen DM, Kovacs TOG, Jutabha R, Gornbein J, Cheng S, King J, Jensen ME. The economic impact of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: cost-effectiveness implications of endoscopic therapy. Hepatology 1999; 29:44–50.

Triantos CK, Goulis J, Patch D, Papatheodoridis GV, Leandro G, Samonakis D, Cholongitas E, Burroughs AK. An evaluation of emergency sclerotherapy of varices in randomized trials: looking the needle in the eye. Endoscopy 2006; 38:797–808.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many residents in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Surgery who played a major role in the care of patients in this study. We thank the many physicians practicing in San Diego, Imperial, Orange, and Riverside counties for their help with patient recruitment, referral, and long-term follow-up. We thank Professors Harold O Conn, Haile T Debas, and Peter Gregory, who served voluntarily as an External Advisory, Data Safety, and Monitoring Committee. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: Isenberg, Orloff, Wheeler; acquisition of data: Haynes, Hye, Isenberg, Jinich-Brook, Orloff, Rapier; drafting of manuscript: Haynes, Hye, Orloff, Vaida; critical revision: Haynes, Hye, Jinich-Brook, Orloff, Vaida; statistical analysis: Isenberg, Orloff, Vaida; guarantor: Marshall J. Orloff, M.D. accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study and has had full access to the data and control of the decision to publish.

Financial support

Supported by grant 1R01 DK41920 from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Surgical Education and Research Foundation (501(c)(3)) (clinicaltrials.gov NCT 00690027). The sponsors played no role in the conduct of the study or in this report of the results and analysis.

Conflicts of interest

There was no conflict of interest relevant to this article on the part of any of the authors and no financial interests, relationship, or affiliations.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Orloff, M.J., Isenberg, J.I., Wheeler, H.O. et al. Direct Costs of Care in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Endoscopic Sclerotherapy versus Emergency Portacaval Shunt for Bleeding Esophageal Varices in Cirrhosis—Part 4. J Gastrointest Surg 15, 38–47 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1332-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1332-6