Abstract

This article investigates students’ access to social capital and its role in their educational decisions in the stratified German school system. We measure social capital as the availability of highly educated adults in adolescents’ and parents’ social networks. Using panel data on complete friendship as well as parental networks and the educational decisions of more than 2700 students from the CILS4EU-DE dataset, we show that social networks are segregated along socio-economic differences, which restricts access to social capital for socio-economically disadvantaged students. A comparison shows that parental networks tend to be substantially more segregated than children’s friendship networks. In addition, our results indicate that access to social capital is linked to academically ambitious choices—i.e., entering upper secondary school or enrolling in university. This relationship is especially pronounced for less privileged students.

Zusammenfassung

Der Beitrag untersucht den Zugang zu Sozialkapital und seine Rolle im Hinblick auf Bildungsentscheidungen im stratifizierten deutschen Schulsystem. Wir messen Sozialkapital durch die Verfügbarkeit von hochgebildeten Erwachsenen in den sozialen Netzwerken von Jugendlichen und ihren Eltern. Durch die Nutzung von Paneldaten, die komplette Freundschaft- und Elternnetzwerke und Bildungsentscheidungen von mehr als 2700 Schülerinnen und Schülern enthalten (CILS4EU-DE), zeigen wir, dass Sozialkapital ungleich über Schultypen verteilt ist und dass Beziehungen innerhalb der Schulen sozial segregiert sind. Im Hinblick auf die Vorteile durch Sozialkapital zeigen unsere Ergebnisse, dass es mit ambitionierten Bildungsentscheidungen – d. h. dem Übergang auf das Gymnasium oder Hochschulen – zusammenhängt. Dieser Befund zeigt sich insbesondere für weniger privilegierte Jugendliche.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many social scientists share the conviction that the reproduction of social inequality is closely linked to education in schools and universities (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990; Bowles and Gintis 1977; Hillmert and Jacob 2005). Within the larger endeavour of understanding the role of these institutions for lasting social inequality, sociologists have argued that educational choices influenced by actors’ socio-economic backgrounds can explain why social inequality persists (Boudon 1974; Jackson and Jonsson 2013; Stocké 2007).

In addition, previous research illustrates that social networks, and the social capital they offer, influence educational outcomes (Cherng et al. 2013; Raabe et al. 2019; Verhaeghe et al. 2015; Roth 2014; Crosnoe et al. 2003; Frank et al. 2008) and that the structure of networks tends to exacerbate inequalities (DiMaggio and Garip 2012; Jackson 2021; Chetty et al. 2022; Granovetter 1995, pp. 139–177). Social capital can increase intergroup inequalities because chances to access, mobilise and benefit from social capital are unequally distributed between social groups (Chetty et al. 2022; Behtoui and Neergaard 2010; DiMaggio and Garip 2012; Lin 2001).

Against this background, we connect networks to educational decisions to investigate (1) whether multiple types of social networks within schools are segregated along socio-economic lines and (2) how the social capital embedded in these networks is linked to educational decisions. In particular, we focus on adolescents’ friendship networks and contacts between their parents to study the formation of social capital—measured as contacts with highly educated parents—and its relationship to academically ambitious educational choices in the German school system.Footnote 1 Therefore, our study contributes to the literature on social capital and its role in labour market outcomes and school-to-work transitions (Behtoui 2007; Roth 2014; Verhaeghe et al. 2015). Moreover, our article is complementary to research on peer effects in the school setting that suggests the presence of classmates with a high socio-economic background is beneficial for students’ educational outcomes (Helbig and Marczuk 2021; Legewie and DiPrete 2012; Zimmermann 2018) by considering how network mechanisms generate social capital in the first place.

Our article offers several new insights by comparing segregation according to households’ socio-economic background in parental and student networks and studying the relationship between social capital and educational decisions. In particular, we consider whether preferences for others with similar backgrounds foster segregation along socio-economic differences above and beyond the opportunity structure for network formation (Wimmer and Lewis 2010). Previous research demonstrated that the opportunity to meet others with a different socio-economic background is limited owing to a combination of factors, such as segregated neighbourhoods (Denessen et al. 2005), school tracking (Jenkins et al. 2008; Karsten 2010) and school choices, which are shaped by households’ educational backgrounds (Jheng et al. 2022). We add to these studies by investigating whether network segregation along socio-economic differences is further exacerbated by relationship choices within schools in multiple types of relationships (i.e., we consider friendship networks and contacts among parents).

Furthermore, we investigated whether the benefits of social capital for educational decisions are more or less pronounced for adolescents without highly educated parents. Analysing differential returns to social capital is important to understand under which conditions social relationships contribute to social inequality or have the potential to mitigate it. Therefore, we answer a call by DiMaggio and Garip (2012), who made the criticism that the analysis of group-specific network effects is often not investigated or reported (for an exception, see Behtoui and Neergaard 2010).

Empirically, we analysed a longitudinal dataset that contains parental and friendship networks of German students in the 9th grade and information on their educational decisions at the end of secondary education. We used the information on students’ classroom-level friendships and contacts between their parents to identify whether students have access to highly educated adults. Recent advances in network analysis (Duxbury 2021; Lusher et al. 2012) allowed us to investigate whether households’ educational backgrounds contribute to the structure of social networks. In particular, these models enabled us to compare whether students’ and parents’ relationship choices restrict the access to social capital for socio-economically disadvantaged households net of compositional differences between schools (Jenkins et al. 2008; Wimmer and Lewis 2010). Subsequently, we employed regression techniques to study how social capital relates to long-term educational outcomes. Complete network data—i.e., information on relationships among all parents and students in a classroom—mitigated the limitations typically associated with self-reports of social relationships, such as a lack of knowledge of others’ characteristics or incorrect recollection of them (Killworth and Bernard 1976; Small 2017; Paik and Sanchagrin 2013; Marsden 1990).

Our results suggest that students’ and parents’ networks are segregated by educational background. Consequently, students from disadvantaged households—who already have fewer chances to access social capital, e.g., owing to neighbourhood segregation—experience a further disadvantage in accessing social capital owing to network formation. Results also show that parental networks exhibit more segregation along socio-economic differences than students’ friendship networks. Furthermore, our analyses reveal that social capital—especially when accessed through parental networks—plays a substantial role in adolescents’ educational decisions. Finally, our findings provide tentative evidence for the notion that social capital is particularly linked to ambitious educational choices when accessed by students from households without a university degree.

2 Theory and Past Research

The notion that social networks affect the outcomes of individuals, organisations and societies is widely shared among social scientists (Coleman 1988; Lin 2001; Burt 2009, 2005; Small 2004; Putnam 2007; Bourdieu 1986). In this regard, the concept of social capital proved useful when studying how individuals benefit from their social environment in various domains, such as the labour market (Granovetter 1995; Coleman 1988; Burt 2005; Behtoui 2016) or educational settings (Dika and Singh 2002; Morgan and Sorensen 1999; Cox 2017). The widespread use of social capital as a conceptual lens has led to diverse definitions of the term (Portes 1998; Fuhse 2021, pp. 37–39). Although some highlight that social capital consists of information and resources embedded in personal networks (Bourdieu 1986; Lin 2001), others understand network structure itself as a form of social capital, e.g. Burt (2005) and Portes (1998) argue that dense networks can facilitate individuals’ adherence to social norms (see also Coleman 1988).

Our study of social capital in the school setting follows a strand of research that studies how information and resources embedded within social relationships can be mobilised by students and parents to realise specific goals, such as school-to-work transitions, college completion, or elevated academic achievement (Verhaeghe et al. 2015; Behtoui and Neergaard 2010; Behtoui 2007; Roth 2014, 2018).Footnote 2

2.1 Scope Conditions for the Mobilisation of Social Capital

Before we derive our theoretical expectations, we would like to point out two qualifications of our conceptualisation of social capital. First, we follow Flap and Völker (2001), who argue that social capital is goal specific because it is not an “all-purpose good” (Flap and Völker 2001, p. 302). For instance, actors’ strategic, work-related network ties can help to achieve a particular goal, such as getting a promotion at work, but may prove less helpful in realising different outcomes, such as job satisfaction regarding social aspects. Consequently, we study how a particular type of social capital—in our case, contact with highly-educated adults via friendship and parental networks—is related to the specific outcome of academically ambitious educational choices at the end of secondary education (Cherng et al. 2013; Helbig and Marczuk 2021; Choi et al. 2008).

However, we do not assume that actors’ mobilisation of social capital is necessarily deliberate, rational or strategic (Lin 1999; Small 2004, 2009), as, for instance, Bourdieu and his collaborators pointed out, perceptual dispositions, transmitted through social interaction or field positions, can reproduce inequality without actors’ deliberate strategizing (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990; Bourdieu 1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992; see also Fuhse 2021). In addition, a conversion between different forms of capital, such as economic, cultural and social capital, takes place in many settings and further complicates studying how social networks affect educational decisions or other life outcomes and vice versa (Lizardo 2006; Lewis and Kaufman 2018; Bourdieu 1986).Footnote 3

The second qualification for our conceptualisation of social capital is that network partners must be willing and able to share their resources and information. Previous scholarship suggests that this might not always be the case, e.g. when societal groups erect physical or symbolic boundaries to exclude others from their accumulated assets (Bourdieu 1984; Lamont 1992; Lamont and Molnár 2002; Tilly 1998; Wimmer 2013). Yet, we are confident that students have access to social capital embedded in their network environments because schools usually foster social interaction between students and parents alike. Although school choices segregate meeting opportunities for crossing socio-economic, racial or ethnic boundaries (Smith et al. 2016; Wimmer and Lewis 2010), we assume that once students are in the same classroom, they at least have the possibility of accessing information and resources through their social relationships. (Small (2009) made a similar argument for the case of childcare centres.) Subsequently, we derive theoretical expectations regarding the formation and usage of social capital in the German school system.

2.2 Network Segregation Along Socio-Economic Differences

Although many studies focus on the effects of social capital on individual outcomes, the question of how the distribution of actors across institutional space and network mechanisms mould access to social capital for socio-economically disadvantaged households is seldom addressed (cf., DiMaggio and Garip 2012). Previous research shows that individuals in high social positions tend to benefit from social capital (Behtoui 2016; Verhaeghe et al. 2015), but the sources of inequality in the access to social capital remain under-investigated. Here, we draw upon network research on segregation in social networks (McPherson 2004; McPherson et al. 2001) to study whether students’ and parents’ relationship choices exacerbate segregation along socio-economic lines.

It is well-known that the socio-economic composition of schools is shaped by neighbourhood segregation (Denessen et al. 2005), school tracking (Jenkins et al. 2008; Karsten 2010), and school choices (Jheng et al. 2022). Therefore, we expect opportunities to form social relationships with others from different socio-economic backgrounds to be restricted owing to the distribution of households between schools.Footnote 4 Relationship choices of students and parents within schools carry the potential to further increase segregation. According to the principle of homophily—in which people who are similar have an increased chance of associating with each other—advantaged children and parents tend to form relationships with similarly advantaged others (Malacarne 2017; McPherson et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2016). Sharing the same socio-economic background often provides fertile ground for forming relationships as actors with a similar socio-economic status tend to share similar tastes, cultural preferences and attitudes (Bourdieu 1984; Chan and Goldthorpe 2007).

H 1

Students and parents from similar socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to form relationships with one another.

Although previous research primarily investigated friendship networks, we analyse parental networks as an additional conduit through which information and resources can flow. This extension is fruitful because contact among parents should be more segregated according to socio-economic differences and is especially consequential for educational decisions. Whereas friendships among students form easily owing to shared foci for interaction (Feld 1981)—e.g. visiting the same classroom or sharing the same way to school—contacts among parents lack such foci for interaction and, thus, require more effort. Therefore, parental networks tend to be sparser and more segregated along socially relevant traits such as households’ migration history (Windzio 2015; Windzio and Bicer 2013). Another difference between students’ and parents’ networks is that friendships among students are characterised by various dimensions such as emotional support, sharing secrets, and helping each other with practical problems such as schoolwork (Kitts and Leal 2021). In contrast, we assume that most contacts among parents are less multi-faceted and predominantly used to exchange school-related information or coordinating their children’s out-of-school activities (Lareau 2011; Small 2009). Following these arguments, we expect that parents’ networks show stronger tendencies of socio-economic homophily than students’ networks.

H 2

Parents show a stronger tendency to form a relationship with others from a similar socio-economic background than students.

To conclude, we hypothesise that relationship choices among students and parents foster unequal access to social capital owing to network segregation and that socio-economic differences are more important for parents’ networks. In the next section, we discuss the potential consequences of unequal access to social capital for educational decisions.

2.3 The Role of Social Capital in Educational Decisions

In Germany, after completing their secondary education, adolescents decide if they will continue schooling and pursue a higher educational degree, start vocational training, or enter the labour market. This choice depends on the type of school students attend: whereas graduates from upper secondary school can enter tertiary education, students from the lower-track, intermediate-track and comprehensive schools are first faced with the decision to enter upper secondary education. Upon completion, these students can also enrol in a university. Therefore, we conceive of enrolment in an upper secondary education (Gymnasium) as an academically ambitious educational decision for students from the lower-track, intermediate-track and comprehensive schools. In comparison, we define pursuing tertiary education as an academically ambitious educational decision for students who attended upper-track schools (Dollmann 2017). Accordingly, we rely on the academic degree of peers’ parents as goal-specific social capital (Cherng et al. 2013; Helbig and Marczuk 2021; Flap and Völker 2001). Contact with highly educated households should foster academically ambitious educational decisions for various reasons. As advantaged individuals are equipped with the resources necessary to succeed in the educational system, they can also be helpful to others by providing direct assistance with homework or assignments (Flashman 2012). Regarding actual educational decisions, highly educated parents can provide information on educational options (Forster and van de Werfhorst 2019) and the possibilities that emerge with a better degree (Barone et al. 2018). Furthermore, they can provide reassurance on the feasibility of, and offer information on, the costs of a potential educational decision (Engelhardt and Lörz 2021; Grodsky and Jones 2007).

Indirectly, highly educated parents and their children can serve as role models because they tend to have higher educational ambitions and aspirations (Breen and Goldthorpe 1997; Stocké 2007), which may spill over to other students, for example, when discussing their academic plans. In a similar vein, they have a habitus that is geared towards the educational system (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990). Hence, we argue that highly educated parents not only positively affect the educational decisions of their children but also positively impact the educational decisions of other students.

H 3

Access to social capital increases the chances of making an academically ambitious decision.

Whereas research shows that network effects tend to benefit those who are already advantaged (DiMaggio and Garip 2012), we argue that—in the current case—adolescents with less educated parents will benefit from social capital. As educational decisions are linked to resources or information that already circulate among highly educated households, these households should experience diminished benefits of their social contacts (see also Helbig and Marczuk 2021). Academic expectations are already relatively high among this group, and ambitious choices tend to be the ‘default choice’. Hence, there is little room for improvement through social capital and a ceiling effect may be observed for this group. In comparison, less privileged households lack resources, information and role models to foster academically ambitious choices. Consequently, social capital should be especially valuable for students from a non-academic background and allow them to compensate for their lack of resources (Choi et al. 2008; Sokatch 2006).

H 4

Social capital is especially beneficial for children from a household without academically educated parents.

3 Data, Measures and Analytical Strategy

3.1 Data

The data for this study were gathered during the CILS4EU project (Kalter et al. 2017) and the CILS4EU-DE extension conducted as a follow-up study in Germany (Kalter et al. 2019). In the initial CILS4EU project, adolescents visiting the 9th grade were surveyed in four European countries (England, Germany, The Netherlands and Sweden). The first wave was conducted in 2010/2011 and the original project collected three waves. This article relies on the German subset of the data. The survey was administered with a two-level strategy. First, a school sample out of all schools hosting ~ 14-year-old adolescents was drawn. In this stage, schools with higher proportions of immigrant students were oversampled. Second, usually two classes per school were randomly selected for participation in the survey. In the first wave of the German part of the survey, 5013 students from 271 classes and 144 schools participated (with a response rate of ~ 80%). In addition to the student surveys, parents also answered a survey in Wave 1 (with a response rate of 78%). As an extension to the initial three waves, the German project team continued their efforts and collected five additional waves, amounting to eight waves in total.Footnote 5 This so-called CILS4EU-DE extension dataset recorded the participants’ educational and labour market careers.Footnote 6

A strength of this dataset is the combination of a panel structure with rich information on adolescents’ social networks. Besides regular survey questions, adolescents also reported their and their parents’ relationships during the first two waves. These sociometric items were designed to capture social networks at the classroom level, such as friendships or parental contacts.

For our analysis, we included students from lower-track schools (Hauptschule), intermediate-track schools (Realschule), comprehensive schools and schools with multiple tracks (Gesamtschule and Schule mit mehreren Bildungsgängen), and upper-track schools (Gymnasium). We excluded students from special needs schools and Rudolf Steiner schools because these school types are conceptually different or showed a sample size that was too small.

Moreover, as we relied on social network information, we excluded schools with a participation rate of less than 75%, because a lower participation rate may provide a bias in the social network information (Smith et al. 2016).Footnote 7 Missing values were imputed by predictive mean matching using the mice package in the statistical software R. We imputed ten datasets and constructed our social capital measure based on each. Our analysis sample consisted of 3998 participants (see Sect. 3.2 for details). However, models investigating educational decisions exclude cases with imputed values on the dependent variable, as this may introduce error. Hence, the sample size for these models was 2749.Footnote 8

3.2 Methods and Analytical Strategy

In the first part of our analysis, we investigated how educational background affects students’ and parents’ relationships within schools. We constructed networks from the reports of all participating adolescents in a classroom. Students were asked: “Who are your best friends in class?” and “Whose parents do your parents get together with once in a while or call each other on the phone?” Participants could name up to five friends and an unlimited amount of parental contacts (see Kruse and Jacob 2014).Footnote 9 These classroom networks formed the basis for studying whether friendship and parental contacts are shaped by students’ educational backgrounds. We also derived our measure of social capital from these networks.

3.2.1 The Structure of Networks

To study how socio-economic differences structure networks, we employed exponential random graph models (ERGMs; Butts 2008; Lusher et al. 2012).Footnote 10 These network models treat the global structure of an observed network as a dependent variable and investigate which local network tendencies—such as reciprocity—account for the network’s global structure (for details, see Lusher et al. 2012). For example, ERGMs can tell the analyst whether relationships between same sex students occur more often in the observed network than a random formation of relationships would suggest, given all other network tendencies accounted for by a particular model specification.

An advantage of ERGMs is that they take the opportunity structure according to a given attribute into account (e.g. the share of female students). Therefore, coefficients for homogeneity reflect the tendency to form ties with others who are similar above and beyond the number of intra-group relationships we would expect based on meeting opportunities (Wimmer and Lewis 2010).Footnote 11 For instance, a positive and statistically significant coefficient for same-sex ties would indicate that relationships are more likely to form among students of the same sex. We used ERGMs to derive estimates that are closer to students’ and parents’ genuine preferences in forming relationships with others who share a similar socio-economic background than descriptive measures (Bojanowski and Corten 2014). Comparable with regression models, analysts must control for other attributes that structure the network, such as their sex (Goodreau et al. 2009), to obtain estimates for the network patterns of interest and reduce the bias due to omitted variables. In summary, these models helped us to test our first hypothesis, that individuals tend to form relationships with others who have the same educational background (same academic degree).

Subsequently, we investigated differences in socio-economic segregation between friendship and parental networks. Owing to their exponential link function, the comparison of estimates between different ERG models is complicated by rescaling issues (Duxbury 2021; for similar issues with logistic regressions, see Mood 2010). Hence, to ensure a valid comparison of estimates, we calculated average marginal effects (AMEs) as recently proposed by Duxbury (2021). The advantages of AMEs are that they are robust against rescaling and allow for a substantial interpretation of coefficients. Also, by interpreting AMEs in relation to the density of a network (i.e., the baseline probability of forming a relationship), effect sizes can be compared between models (Kreager et al. 2021). Scaled AMEs can be interpreted as a change in the baseline probability to form a relationship if a network variable increases by one unit. For example, scaled AMEs for the same-sex coefficient tells us how much the overall probability of forming a friendship increases if two students share the same sex.

3.2.2 Social Capital Embedded in Networks

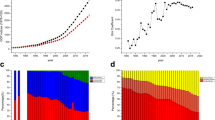

Although ERGMs help us to investigate whether relationships are structured along socio-economic differences, we now turn to the question of how individuals access social capital through their personal networks. To measure social capital, we first assigned the highest educational background of parents to each student. For this, we mostly relied on the parental questionnaire and substituted missing values with children’s reports. We extracted the personal network—i.e. ego networks—of each student and parent from the respective classroom-level network. Afterwards, we identified whether students have at least one friend who has a parent with an academic degree (see Fig. 1a, b). Similarly, we determined whether students’ parents have contact with at least one other parent with a university degree. The rationale behind this measurement is that we assume that one person in the network who can provide relevant information is sufficient to foster the observed educational decision.Footnote 12

a Sample ego networks of two students. The figure shows a theoretical sample friendship network. Students with a “1” have at least one academically educated parent. Although visual inspection suggests that students from highly educated households might tend to befriend each other in this network (see bottom left corner), ERG models allow us to identify whether this clustering is significantly different from randomness by considering other factors, such as students’ sex. As an example, two students are highlighted: Student A and Student B. Their respective ego networks can be seen in Fig. 1b. b Ego networks of Student A and Student B. The left figure shows the ego network of student A and the right the ego network of student B (see Fig. 1a). Although Student A does not have friends with academically educated parents, Student B has one such friend (indicated by “1”). Thus, for our purposes, Student B has social capital because she has “at least one” friend with academically educated parents. Student A does not have social capital

Information obtained through complete social network data is considerably less biased because participants do not have to know, remember or be aware of others’ characteristics (Marsden 1990); they solely have to report their own relationships. This is particularly useful when investigating adolescents’ social networks in combination with parental interviews because previous research shows that adolescents tend to have problems accurately reporting parents’ educational degrees (Engzell and Jonsson 2015).

In sum, we obtain two binary social capital measures: (1) students have at least one friend who has a parent with a university degree (0/1); (2) students’ parents have contact with at least one parent with a university degree (0/1).

3.2.3 Consequences of Social Capital: Linear Probability Models and Causality

In the second part of our investigation, we focused on the role of social capital for individual educational decisions, making use of the longitudinal structure of the dataset. We treated students’ academically ambitious choices as the dependent variable and social capital as the main predictor in a regression framework. We employed linear probability models (LPMs) with school class fixed effects and clustered standard errors at the classroom level.

Our aim is to elaborate a connection between social capital and educational decisions that accounts for several sources of potential biases. Yet, we acknowledge that estimating the causal effects of networks on individual attributes is seldom feasible with observational data (for details, see Shalizi and Thomas 2011).

Researchers encounter several methodological challenges when identifying causal effects of social capital on educational or labour market outcomes (Mouw 2006). Unobserved heterogeneity due to the self-selection of individuals into social relationships and reverse causality may inflate estimates of the effect of social capital. Taking all relevant characteristics connected to relationship choices into account can solve the issue of unobserved heterogeneity. However, surveys often cannot provide measurements for all factors shaping networks. Therefore, it is complicated to establish causality (Elwert and Winship 2014; Mouw 2006; Shalizi and Thomas 2011). We addressed this issue by controlling for a variety of confounders and including classroom-level fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity between classrooms.

Another advantage of our analytical strategy is that it did not have the common issue of reversed causality because our social capital measures stemmed from social networks several years before the educational decisions analysed. Hence, although we cannot establish causal effects, our approach improves upon previous studies—especially studies that followed a cross-sectional design (see also Roth and Weißmann 2022).

3.3 Measurements

3.3.1 Dependent Variables in Regression Analyses

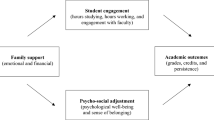

We investigated two types of educational decisions depending on the school track students visited (see Fig. 2). First, we assessed the decision to enter the academic track after the 10th grade for students from the lower and intermediate tracks and for comprehensive school students (including schools with several educational tracks, see ED1 in Fig. 2). Second, we considered the decision to enrol in university for students initially attending the academic track and for intermediate-track and comprehensive school students who previously decided to visit the academic track (i.e., ED1, see ED2 in Fig. 2).Footnote 13

Stylized version of German secondary education highlighting the educational decisions investigated. (Figure adapted from Dollmann and Weißmann 2019)

For this purpose, we used the CILS4EU-DE data from Waves 3 to 7. In each wave, participants were asked what they were “currently doing” regarding their educational and labour market situation. The options were “School”, “Apprenticeship/work-related training”, “Studying”, “Full-time job”, “Internship”, or “Something else”. If participants answered that they were currently in “School”, they were asked what kind of school they were attending.

Based on this information, for ED1, we identified lower-track, intermediate-track, and comprehensive-school students who reported that they attended the Gymnasium in at least one of the waves. For ED2, we identified academic-track students as well as intermediate-track and comprehensive-school students who reported that they were “studying” in at least one of the waves. The reference category contains all participants who chose the labour market, vocational training, or dropped out. Because of this reference category, we restricted the sample of the non-academic-track students in ED2 to those who had already realised ED1. Therefore, we excluded students who already made their educational decision towards vocational education or the labour market at an earlier stage, which would otherwise inflate the reference category.

We assigned an ambitious choice to students who made an upward decision after having left school, regardless of the timing of that decision. Hence, we included choices that occurred some years after students’ graduation because some students do not follow the usual timeframe owing to school year repetition, gap years or voluntary service (see appendix for a more detailed explanation).

3.3.2 Independent Variables in Regression Analyses

Concerning the LPMs investigating the consequences of social capital, we added a set of control variables, which previous research identified as relevant for relationship choices and educational decisions. We controlled for students’ parents with an academic background. Of the two parents, we obtained the highest educational level and assigned a “1” to students with one parent holding a university degree. Although Engzell and Jonsson (2015) showed that adolescents have problems accurately reporting their parents’ educational background, the CILS4EU project also conducted parental interviews in which parents provided information about their academic degrees. Therefore, when possible, we relied on parental reports to assess their educational background. For 85.49% of our analysis sample, the information provided by parents was available and the missing information was substituted by adolescents’ reports (with 15 missing values remaining).

We controlled for socio-economic status by using the International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI). This index captures the occupational status according to educational and income levels and ranges from 11 to 89. To avoid missing values, we assigned the value “10” if both parents are unemployed (see Plenty and Mood 2016) and divided the index by 10 so that our final index ranges from 1 to 8.9. Here, we also relied on parental reports when possible and substituted adolescents’ reports when necessary (with 102 missing values remaining).

Furthermore, we controlled for students’ ethnic group membership and considered several groups based on adolescents’ and their parents’ countries of origin. We utilised the pre-coded ethnic background variables provided in the CILS4EU dataset to differentiate between the following categories (see Dollmann et al. 2014): Germany, Turkey, Former Soviet Union, Poland, Former Yugoslavia, Italy, Non-Western, Western, and Other (with no missing values).

Regarding educational aspirations, students were asked, “What is the highest level of education you wish to get?”. The answer categories were (0) “No degree”, (1) “Degree from lower secondary school (Hauptschulabschluss)”, (2) “Degree from intermediate school (Realschulabschluss)”, (3) “Degree from upper secondary school (Abitur)”, and (4) “University degree”. From this question, we constructed three categories: (0) “Below upper secondary school degree”, (1) “degree from upper secondary school”, and (2) “university degree”. In our analyses “below upper secondary school degree” served as the reference category (51 missing values). Similarly, parents were asked, “What is the highest level of education you wish your child to get?” We derived a measure for parental aspirations that followed the above-mentioned scheme (36 missing values).

Regarding students’ school grades, we used the grades of the subjects “German”, “Maths”, and “English”. The German grading system ranges from 1 (very good) to 6 (insufficient). To ease interpretation, we recoded the variables ranging from “0” to “5”, where higher values reflect better grades. We averaged the grades across the above-mentioned subjects (66 missing values).

Last, to account for the opportunity to access social capital, we controlled for the outdegree—that is, the number of friends a student reports or the number of parental contacts respectively. We derived this information from classroom level networks of friendships and parental contacts. The construction of networks is described in Sect. 3.2.

3.3.3 Independent Variables in Network Models

Concerning the exponential random graph models (ERGMs), we focused on the socio-demographic control variables sex, ethnic minority status and educational background, following previous research on adolescents’ social networks (Goodreau et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2016). Based on these characteristics, we controlled for the tendency to have same-sex relationships (same sex), and whether two individuals with the same migration history are more likely to have a relationship (same majority/minority). Moreover, we investigated whether the same educational background increases the chances of forming a relationship (same academic background). In addition, we assessed whether children with highly educated parents are more active in their networks (activity academic degree), or whether they are chosen more often as their network partners (popularity academic degree). Activity refers to the number of nominations a person sends, and popularity refers to the number of nominations a person receives from others. We also included these effects for gender (activity female and popularity female). Since parents’ networks are undirected, we only captured the extent to which university-educated parents and parents of girls have more ties in total.Footnote 14

4 Results

4.1 Summary Statistics

Tables 1 and 2 summarise the statistics for both analysis samples. Additionally, we provided statistics that were differentiated for those with and without an ambitious decision. Although just around a quarter of students who finished the 10th grade on track other than the upper track transitioned to the academic track (ED1; Table 1), almost 70% of adolescents who attended the upper track enrolled in a university (ED2; Table 2). When comparing individuals with and without ambitious decisions, a substantially larger share of those who make an ambitious decision have access to social capital. Especially, when comparing social capital accessed through parental networks, the share is around twice as large. This descriptive overview already points to the relevance of social capital for educational decisions.

Regarding the institutional differences in social capital access, Table 3 shows the high degree of segregation by educational background between school types. Although around 47% of the students in the highest track belong to households with at least one highly educated parent, only about 6% of children in the lower and 14% in the intermediate track have a university-educated parent. These compositional differences also translate into unequal access to social capital across school types. Around 20% of students in the lower track have access to social capital, whereas more than 85% of upper-rack students have at least one friend with highly educated parents.

In general, parental networks offer less access than their children’s relationships and upper-track schools allow more students to access social capital. The higher number of highly educated parents in this track may explain this pattern. However, prior work on parental involvement also shows that socio-economically advantaged parents are more involved in their children’s school life (Lareau 2011), which elevates their chances of accessing social capital. To conclude, our results illustrate that the distribution of adolescents across school types is closely linked to their access to social capital.

4.2 Measuring Segregation with Network Models

In the next step, we performed ERGMs to investigate the relationship patterns among adolescents (Table 4) and their parents (Table 5) within schools.Footnote 15 Coefficients indicate whether particular local network structures appear more often than expected by random chance when considering all other parameters in a specification. For instance, the same-sex coefficients reflect whether students tended to befriend same-sex peers more often than classmates of the opposite sex.

In support of our theoretical expectations, the results show that adolescents and parents tend to select others with similar educational backgrounds, leading to segregated networks: Relationships between two individuals with the same educational background are more likely than relationships across educational groups. Besides the institutional restrictions to accessing social capital (i.e. between school type differences), relationship patterns restrict access even further for those without a university background above and beyond the opportunity structure.

Moreover, highly educated parents are better connected in parental networks, which aligns with our descriptive findings. However, friendship and parents’ networks in lower-track schools are exceptions to these patterns. Here, students did not show a preference for those similar to them regarding educational background.

Scaled AMEs in Tables 4 and 5 allow us to compare the extent of network segregation in friendship and parental networks. When comparing the scaled AMEs, we find support for our second hypothesis: Parental networks tend to be substantially more segregated by educational background than friendship networks. In all school types, except for lower-track schools, the chances of two parents forming a relationship is around twice as high as that of two adolescents with academically educated parents. For example, in higher-track schools, the baseline probability of forming a friendship increases by 26%. In comparison, this probability increases by 192% for same-sex adolescents and by 45% for two minority (or majority) adolescents. Hence, the extent of socio-economic segregation is smaller than that of ethnic segregation or sex segregation. Nevertheless, socio-economic network segregation results in a social capital deficit for households without a university education, especially concerning social capital accessed through parental networks.

Taken together, these findings suggest that access to social capital is not only restricted by differences in the opportunity structure across schools—as highly educated families tend to cluster in the upper track—but also because of the formation of social relationships within schools. Moreover, parents tend to segregate more according to their academic backgrounds than their children.

4.3 Social Capital and Ambitious Choices

This section investigates whether adolescents’ academically ambitious choices are associated with their social capital. We present the results for two different decisions: (1) the decision to enter the academic track in Table 6 (i.e. ED1 in Fig. 2) and (2) the decision to enrol in a university in Table 7 (i.e. ED2 in Fig. 2).

Our results indicate that social capital is associated with both educational decisions, which aligns with the third hypothesis. There are, however, slight differences between the investigated decisions. Considering the decision to go to university (Table 7), social capital embedded in friendship (b = 0.13, p < 0.05) as well as parental networks (b = 0.11, p < 0.01) shows a significant association. The magnitude of the association is comparable with that of other established factors associated with ambitious choices, such as academic background (b = 0.09, p < 0.01).

Regarding the decision to enter the academic track (Table 6), only social capital embedded in parental networks shows a significant association (b = 0.10, p > 0.10). Moreover, this association is only marginally significant, but in a similar magnitude to that of students’ (b = 0.1, p > 0.001) and parents’ (b = 0.1, p > 0.01) aspirations to obtain a degree from upper secondary school.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, taken together, these results provide evidence for the third hypothesis, which states that social capital is beneficial for academically ambitious educational decisions.

In the next step, we investigate how social capital is related to educational decisions for individuals with and without an academic family background. To this end, we split the sample by academic background. For both educational decisions (Tables 6 and 7), the results suggest that social capital might be particularly beneficial for students from households without a university degree, providing evidence for our fourth hypothesis.

Model 2a in Table 6 shows that social capital embedded in parental networks of families without a university degree increases the chances of entering the academic track by 15% (b = 0.15, p < 0.05), making social capital comparable with an improvement of one school grade (b = 0.12, p < 0.001). Table 7 shows a similar picture. For non-academic families (Model 2b), social capital accessed by students (b = 0.15, p < 0.1) and their parents (b = 0.1, p < 0.1) is associated with entering university.

On the other hand, the results for social capital embedded in networks of families with tertiary education provide less evidence for either educational decision. To avoid overinterpretation of our results, we point out that social capital accessed by students from households with a university degree (Table 7, Model 3b) is almost statistically significant at the 10%-level and may, therefore, also play a role in adolescents’ educational careers (b = 0.14, p > 0.1). Nevertheless, taking all the results together, we find indicative evidence for our fourth hypothesis, that social capital is beneficial for households without academically educated parents, especially when embedded in parental networks.

To summarise, our models reveal that social capital provides various benefits regarding adolescents’ educational decisions. Social capital embedded in adolescents’ and parental networks seems to play a distinct role in students’ decisions to enrol in universities. In comparison, social capital embedded in parental networks appears to be more relevant to adolescents’ decision to enter upper-track schools after finishing the 10th grade on a different school track. Additionally, our results provide tentative evidence that social capital seems to be particularly useful when accessed by households without academically educated parents. For these families, social capital may be a substitute for a lack of resources at home.

5 Discussion

Our study addressed the interplay between socio-economic background, social networks, and educational decisions in the German school system. We analysed the networks and educational decisions of over 2700 students with network models and regression techniques to investigate the formation of social capital and its link with academically ambitious educational choices. In general, the analyses supported our theoretical expectations and highlight the importance of social capital in the academic setting.

Our results revealed that students and parents tend to form relationships with others who share the same educational background. However, parents tend to form relationships based on socio-economic differences more often than their children. This difference may be explained by more opportunities in adolescents’ school life to connect with their peers (Feld 1981). However, it may also be explained by parents’ higher selectivity with regard to relationship partners (Windzio and Bicer 2013).

In addition, the findings indicate that social capital embedded in students’ friendships and parental networks fosters academically ambitious choices. We find that parents’ social capital is beneficial for both educational decisions studied, which again highlights the relevance of parents in their children’s educational careers (Hoenig 2019; Roth 2018; Roth and Weißmann 2022). In comparison, social capital accessed through students’ friendship networks only shows a clear link to the decision to visit university. A possible explanation for this difference could be that adolescents’ agency regarding their educational careers increases as students grow older, which may also increase the relevance of the networks in which they are embedded.

Moreover, at a younger age, children’s friendships may be less reliable circuits for social capital than parental contacts. Even if friends come from highly educated households, it is unclear whether further conditions for accessing social capital—such as visiting these households—are fulfilled. If friendships with peers from advantaged households are restricted to the school setting, social capital might show diminished benefits for ambitious academic decisions.

The more substantial role of social capital accessed through relationships among parents may also be explained by differences in relationship choices and content at this earlier stage of the educational career. Friendships encompass many aspects, such as mutual expectations, trust or school advice (Kitts and Leal 2021), which may evolve during different life stages. Further research is necessary to clarify under which conditions social capital embedded in students’ relationships has its positive effects.

We also find tentative evidence for the notion that social capital is particularly beneficial for adolescents from less privileged households. For these families, social capital may substitute for a lack of resources, which provides them with a path towards more advanced schooling and degrees. However, considering our results together, our study highlights that the necessary preconditions for such a compensation mechanism are often not fulfilled: school choices, and thereby the opportunity to meet peers from a highly-educated household, are shaped by parents’ socio-economic characteristics. In addition, relationships within schools are segregated according to students’ educational backgrounds. Further research should investigate which factors facilitate crossing these boundaries between and within schools to improve access to social capital for those social groups that might benefit most from it.

Our article contributes to the existing literature in several ways. We used complete networks of multiple types of social relationships (i.e. adolescents’ friendships and contacts between parents), which enabled us to generate novel findings. The analysis of complete networks allowed us to identify patterns indicative of segregation according to socio-economic differences above and beyond the opportunity structure. In addition, our study highlights that parents’ networks are more segregated than friendship networks and reveal the central role of social capital accessed through parental networks for educational outcomes, whereas many network studies have focused on friendship or advice networks (Cherng et al. 2013; Crosnoe et al. 2003; Raabe et al. 2019; Roth 2018; Roth and Weißmann 2022; Smith et al. 2016).

Our study investigated group-specific outcomes of social networks and linked them to the greater discourse on social inequality (DiMaggio and Garip 2012). Complete classroom-level networks allowed us to ensure the robustness of our results regarding potential biases stemming from self-reports and add to the previous literature by highlighting the importance of social capital for educational careers (Behtoui 2016; Roth 2014, 2018; Verhaeghe et al. 2015).

Moreover, as the data used here stem from the highly stratified German school system, we provide a conservative test for the notion that social capital is beneficial, as students are already pre-sorted into different school tracks and educational careers (Roth 2017). Considering the German school system, however, it is conceivable that social capital may be more relevant after elementary school. First, parents may need to rely more on their social resources owing to the variety of educational options at this decisive point in their children’s educational career. Second, providing social capital access to families without academically educated parents—e.g., by reducing the socio-economic segregation of neighbourhoods or social networks—may be especially beneficial in improving their children’s educational prospects. As the social selectivity at this stage of the German school system is particularly high (Ehmke and Siegle 2005), fostering relationships between less and more educated parents at this early stage may increase the chances of less advantaged children attending higher school tracks owing to the provision of information or knowledge of challenges and subsequent steps ahead.

We acknowledge several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, we did not establish a causal effect of social capital. With the observational data at hand, we could not rule out unobserved latent homophily regarding relationship patterns (Shalizi and Thomas 2011). However, we took multiple steps to address this issue by employing a longitudinal analytical setup: our measurement of social capital and the educational decisions are a couple of years apart. To account for endogenous selection, we controlled for relevant socio-demographic and other variables associated with the outcome and selection. Moreover, we employed fixed effects at the classroom level: This approach accounts for unobserved and observed heterogeneity between classes and the selection of students in classrooms. Thus, this procedure rules out alternative explanations at the contextual level, such as class composition, teacher effects or regional differences. Although we were unable to identify a causal effect, our approach took important steps in this direction (Roth and Weißmann 2022; Verhaeghe et al. 2015).

Second, we relied on nominations within classes. Although adolescents spend an extensive amount of time with their classroom peers, and these relationships can be considered particularly important for their educational development (Legewie and DiPrete 2012; Zimmermann 2018), we did not consider how social capital may have been accessed outside the school context. Although adolescents have a significant share of friends from their class, omitting parental contacts outside school could lead to potential biases. Parents can access social capital in their neighbourhoods, workplace or voluntary associations. However, as these social foci tend to be segregated according to socio-economic status and ethnic background (McPherson 2004), the chances of socio-economically disadvantaged parents accessing social capital are potentially reduced—though certainly not impossible.

Moreover, we relied on adolescents’ reports of their parents’ contacts. Arguably, this is not ideal as adolescents might not be aware of all the communication between their parents. It would be preferable to obtain parental contacts directly from parents. Although parental surveys were administered in CILS4EU, this network information was not gathered, likely because of the challenges associated with collecting complete network information. Other research projects conducting complete parental networks followed a similar approach (e.g. Bicer et al. 2014). Future projects may improve on the measurement of parental networks by gathering information directly.

Third, we have not answered the question of how social capital is generated to its full extent. More specifically, we did not address the conversion between different forms of capital, especially from cultural capital to social capital (Bottero and Crossley 2011; Lewis and Kaufman 2018; Lizardo 2006, 2016). As cultural capital can be considered particularly relevant in the educational system (Jæger and Breen 2016; Bourdieu and Passeron 1990), more research should focus on how advantages in cultural capital may translate into social network advantages in schools.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings provide a fertile ground for future research on the role of social capital through different sources for educational decisions and intergenerational mobility more broadly.

Notes

We understand academically ambitious choices as the transition from lower track, intermediate track, and comprehensive schools into the academic track, and from upper track schools as well as (for the subset of students who realised the first decision) from intermediate track and comprehensive schools into higher education—as opposed to vocational education or the labour market.

Note that another branch of the literature studies how densely connected social networks and intergenerational closure—i.e., when students’ parents are acquainted—bolster educational outcomes (Geven and van de Werfhorst 2020; Morgan and Sorensen 1999). Studying both types of social capital would go beyond the scope of our investigation but is an exciting avenue for future research.

Although we acknowledge the possible conversion of different forms of capital and control for other types of capital in addition to social capital, such as households’ educational background, in our analyses, modelling conversion dynamics in detail would go beyond the scope of our investigation.

The German school system consists of three secondary school tracks, which are hierarchically ordered according to students’ prior academic abilities: lower (Hauptschule), intermediate (Realschule), and upper secondary (Gymnasium). Additionally, the school system offers comprehensive schools, which combine these three school tracks and allow students to obtain a certificate that is necessary to go to university. Research shows that the allocation of students is significantly structured by a child’s background: children with an advantaged socio-economic background are more likely to attend the higher tracks than socio-economically disadvantaged children (Jenkins et al. 2008; Kristen and Granato 2007; Solga and Wagner 2010). Consequently, a higher share of the student body in upper secondary schools comes from advantaged households, as opposed to the other school types. This first step restricts the opportunities for relationships because the composition of a context determines the pool of possible interaction partners (Blau 1994).

The 8th wave was released after finishing the data analysis of this project.

In addition to the original sample, in Wave 6, a refreshment sample of around 3000 individuals was drawn to make up for panel attrition. However, as we connect information from Wave 1 with the later waves, we did not use this refreshment sample.

This rule led to the exclusion of around 28% of classes (for a similar sample reduction, see Smith et al. 2016).

Additional analyses do not reveal any substantial bias regarding panel drop-out on relevant variables. However, minor differences can be seen regarding adolescents’ educational aspirations and ethnic origin. Students with very high university aspirations and students from the former Soviet Union and non-Western countries have a higher chance of remaining in the sample (see Table 8 in the appendix).

Although we considered the directedness of the friendship network, we treated the parental network as an undirected network. If researchers conceptualize a network as undirected, they assume that relationships are reciprocal or symmetric and lack directionality. Examples of undirected networks are co-presence ties (i.e. actors spending time together) or communication ties established by two actors engaging in a conversation. In both cases, researchers usually choose an undirected network to represent relations because being co-present or communicating involves both actors automatically. In comparison, directed networks allow researchers to consider relationships that can be one-sided or oriented from one person to another. For instance, friendships can be unreciprocated—if actor A believes B to be their friend, but B does not—and therefore, it is often fruitful to represent them as a directed network (Wasserman and Faust 1994). The rationale behind this is that the question capturing the parental networks does not indicate directionality. Moreover, we believe that some students may not have known about the contacts their parents have, whereas others did.

We used the ergm function of the statnet package (v. 2019.6) in R.

Other applications of ERGMs also control for endogenous network processes, such as triadic closure (e.g. Wimmer and Lewis 2010). We decided to estimate specifications without higher-order terms because they can complicate the interpretation of coefficients, especially if analysts are interested in the role of node attributes for network structure (see Martin (2020) for a similar line of argumentation).

We also investigated whether the number of contacts or the share of contacts with an academic background provide benefits for educational choices. These results show that the threshold lies between ‘0’ and ‘1’ contacts to individuals with academic background. Our models do not suggest that additional contacts provide additional benefits. A larger share of contacts with an academic background—although estimates point in the same direction—is not statistically significant in most models. Results are available upon request.

For ED2, we decided to drop lower-track students because case numbers were relatively small. Few students had social capital in the way in which we conceptualised it and/or enrolled in universities. Although we find a strong positive association between social capital and the decision to enrol in university for lower-track students, we do not want to introduce bias because of the very small case numbers.

We estimated additional models only entailing educational background as an independent variable. Results remain qualitatively similar in these more basic specifications and are available upon request.

As small and sparse networks (e.g. parents’ networks) tend to produce convergence issues, we constructed the respective matrices for each school type separately (for a similar approach combining all classroom-level networks of one school, see Kruse et al. 2016).

Academic family background does not remain significant after controlling for school grades and educational aspirations in this model.

References

Barone, Carlo, Giulia Assirelli, Giovanni Abbiati, Gianluca Argentin and Deborah De Luca. 2018. Social origins, relative risk aversion and track choice: A field experiment on the role of information biases. Acta Sociologica 61:441–459.

Behtoui, Alireza. 2007. The distribution and return of social capital: Evidence from Sweden. European Societies 9:383–407.

Behtoui, Alireza. 2016. Beyond social ties: The impact of social capital on labour market outcomes for young Swedish people. Journal of Sociology 52:711–724.

Behtoui, Alireza, and Anders Neergaard. 2010. Social capital and wage disadvantages among immigrant workers. Work, Employment and Society 24:761–779.

Bicer, Enis, Michael Windzio and Matthias Wingens (eds.). 2014. Soziale Netzwerke, Sozialkapital und ethnische Grenzziehungen im Schulkontext. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Blau, Peter Michael. 1994. Structural contexts of opportunities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bojanowski, Michał, and Rense Corten. 2014. Measuring segregation in social networks. Social Networks 39:14–32.

Bottero, Wendy, and Nick Crossley. 2011. Worlds, fields and networks: Becker, Bourdieu and the structures of social relations. Cultural Sociology 5:99–119.

Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, opportunity, and social inequality: Changing prospects in western society. New York: Wiley.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. J. Richardson, 241–258. New York: NY: Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean Claude Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in education, society, and culture. London; Newbury Park, Calif: Sage.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bowles, Samuel, and Herbert Gintis. 1977. Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. New York: Basic Books.

Breen, Richard, and John H. Goldthorpe. 1997. Explaining educational differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society 9:275–305.

Burt, Ronald S. 2005. Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burt, Ronald S. 2009. Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press.

Butts, Carter T. 2008. Social network analysis with sna. Journal of statistical software 24:1–51.

Chan, Tak Wing, and John. H. Goldthorpe. 2007. Social stratification and cultural consumption: Music in England. European Sociological Review 23:1–19.

Cherng, Hua-Yu Sebastian, Jessica McCrory Calarco and Grace Kao. 2013. Along for the Ride: Best Friends’ Resources and Adolescents’ College Completion. American Educational Research Journal 50:76–106.

Chetty, Raj et al. 2022. Social capital II: Determinants of economic connectedness. Nature 608:122–134.

Choi, Kate H., R. Kelly Raley, Chandra Muller and Catherine Riegle-Crumb. 2008. Class composition: Socioeconomic characteristics of coursemates and college enrollment. Social Science Quarterly 89:846–866.

Coleman, James S. 1988. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology 94:S95–S120.

Cox, Amanda Barrett. 2017. Cohorts, ‘siblings,’ and mentors: Organizational structures and the creation of social capital. Sociology of Education 90:47–63.

Crosnoe, Robert, Shannon Cavanagh and Glen H. Elder. 2003. Adolescent friendships as academic resources: The intersection of friendship, race, and school disadvantage. Sociological Perspectives 46:331–352.

Denessen, Eddie, Geert Driessena and Peter Sleegers. 2005. Segregation by choice? A study of group-specific reasons for school choice. Journal of Education Policy 20:347–368.

Dika, Sandra L., and Kusum Singh. 2002. Applications of social capital in educational literature: A critical synthesis. Review of Educational Research 72:31–60.

DiMaggio, Paul, and Filiz Garip. 2012. Network effects and social inequality. Annual Review of Sociology 38:93–118.

Dollmann, Jörg. 2017. Positive choices for all? Ses- and gender-specific premia of immigrants at educational transitions. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 49:20–31.

Dollmann, Jörg, and Markus Weißmann. 2019. The story after immigrants’ ambitious educational choices: Real improvement or back to square one? European Sociological Review 36:32–47.

Dollmann, Jörg, Konstanze Jacob and Frank Kalter. 2014. Examining the diversity of youth in Europe. A classification of generations and ethnic origins using CILS4EU data (technical report). Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung: Arbeitspapiere 156.

Duxbury, Scott W. 2021. The problem of scaling in exponential random graph models. Sociological Methods & Research 1–39.

Ehmke, Timo, and Thilo Siegle. 2005. ISEI, ISCED, HOMEPOS, ESCS. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 8:521–539.

Elwert, Felix, and Christopher Winship. 2014. Endogenous selection bias: The problem of conditioning on a collider variable. Annual Review of Sociology 40:31–53.

Engelhardt, Carina, and Markus Lörz. 2021. Auswirkungen von Studienkosten auf herkunftsspezifische Ungleichheiten bei der Studienaufnahme und der Studienfachwahl. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 73:285–305.

Engzell, Per, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2015. Estimating social and ethnic inequality in school surveys: Biases from child misreporting and parent nonresponse. European Sociological Review 31:312–325.

Feld, Scott L. 1981. The focused organization of social ties. American Journal of Sociology 86:1015–1035.

Flap, Henk, and Beate Völker. 2001. Goal specific social capital and job satisfaction: Effects of different types of networks on instrumental and social aspects of work. Social networks 23:297–320.

Flashman, Jennifer. 2012. Academic achievement and its impact on friend dynamics. Sociology of Education 85:61–80.

Forster, Andrea G, and Herman G. van de Werfhorst. 2019. Navigating institutions: Parents’ knowledge of the educational system and students’ success in education. European Sociological Review 48–65.

Frank, Kenneth A., Chandra Muller, Kathryn S. Schiller, Catherine Riegle-Crumb, Anna Strassmann Mueller, Robert Crosnoe and Jennifer Pearson. 2008. The social dynamics of mathematics coursetaking in high school. American Journal of Sociology 113:1645–1696.

Fuhse, Jan. 2021. Theories of social networks. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Networks, eds. Ryan Light and James Moody, 34–49. Oxford University Press.

Geven, Sara, and Herman G. van de Werfhorst. 2020. The Role of Intergenerational Networks in Students’ School Performance in Two Differentiated Educational Systems: A Comparison of Between- and Within-Individual Estimates. Sociology of Education 93:40–64.

Goodreau, Steven M., James A. Kitts and Martina Morris. 2009. Birds of a feather, or friend of a friend? Using exponential random graph models to investigate adolescent social networks. Demography 46:103–125.

Granovetter, Mark S. 1995. Getting a job: A study of contacts and careers. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Grodsky, Eric, and Melanie T. Jones. 2007. Real and imagined barriers to college entry: Perceptions of cost. Social Science Research 36:745–766.

Helbig, Marcel, and Anna Marczuk. 2021. Der Einfluss der innerschulischen Peer-Group auf die individuelle Studienentscheidung. Journal for Educational Research Online 2021:30–61.

Hillmert, Steffen, and Marita Jacob. 2005. Institutionelle Strukturierung und inter-individuelle Variation. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 57:414–442.

Hoenig, Kerstin. 2019. Soziales Kapital und Bildungserfolg: Differentielle Renditen im Bildungsverlauf. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Jackson, Matthew O. 2021. Inequality’s economic and social roots: The role of social networks and homophily. Available at SSRN 3795626.

Jackson, Michelle, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2013. Why does inequality of educational opportunity vary across countries? In Determined to Succeed? Ed. Michelle Jackson, 306–338. Stanford University Press.

Jenkins, Stephen P., John Micklewright and Sylke V. Schnepf. 2008. Social segregation in secondary schools: How does England compare with other countries? Oxford Review of Education 34:21–37.

Jheng, Ying-jie, Chun-wen Lin, Jason Chien-chen Chang and Yuen-kuang Liao. 2022. Who is able to choose? A meta-analysis and systematic review of the effects of family socioeconomic status on school choice. International Journal of Educational Research 112:101943.

Jæger, Mads Meier, and Richard Breen. 2016. A dynamic model of cultural reproduction. American Journal of Sociology 121:1079–1115.

Kalter, Frank et al. 2017. Children of immigrants longitudinal survey in four European countries (CILS4EU)—reduced version. Reduced data file for download and off-site use. https://dbk.gesis.org/dbksearch/sdesc2.asp?no=5656&db=e&doi=10.4232/cils4eu.5656.3.3.0. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Kalter, Frank, Irena Kogan and Jörg Dollmann. 2019. Children of immigrants longitudinal survey in four European countries—Germany (CILS4EU-DE)—reduced version. Reduced data file for download and off-site use. https://dbk.gesis.org/dbksearch/sdesc2.asp?no=6656&db=e&doi=10.4232/cils4eu-de.6656.4.0.0. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Karsten, Sjoerd. 2010. School segregation. In Equal opportunities? The labour market integration of the children of immigrants, 193–209. OECD.

Killworth, Peter D., and H. Russell Bernard. 1976. Informant accuracy in social network data. Human Organization 269–286.

Kitts, James A., and Diego F. Leal. 2021. What is(n’t) a friend? Dimensions of the friendship concept among adolescents. Social Networks 66:161–170.

Kreager, Derek A., Jacob T. N. Young, Dana L. Haynie, David R. Schaefer, Martin Bouchard and Kimberly M. Davidson. 2021. In the eye of the beholder: Meaning and structure of informal status in women’s and men’s prisons. Criminology 59:42–72.

Kristen, Cornelia, and Nadia Granato. 2007. The educational attainment of the second generation in Germany: Social origins and ethnic inequality. Ethnicities 7:343–366.

Kruse, Hanno, and Konstanze Jacob. 2014. Sociometric fieldwork report. Children of immigrants longitudinal survey in 4 European countries. wave 1‑2010/2011, v1.1.0. Mannheim.

Kruse, Hanno, Sanne Smith, Frank van Tubergen and Ineke Maas. 2016. From neighbors to school friends? How adolescents’ place of residence relates to same-ethnic school friendships. Social Networks 44:130–142.

Lamont, Michèle. 1992. Money, morals, and manners: The culture of the French and the American upper-middle class. University of Chicago Press.

Lamont, Michèle, and Virág Molnár. 2002. The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28:167–195.

Lareau, Annette. 2011. Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. 2nd ed., with an update a decade later. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Legewie, Joscha, and Thomas A. DiPrete. 2012. School context and the gender gap in educational achievement. American Sociological Review 77:463–485.

Lewis, Kevin, and Jason Kaufman. 2018. The conversion of cultural tastes into social network ties. American Journal of Sociology 123:1684–1742.

Lin, Nan. 1999. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections 22:28–51.

Lin, Nan. 2001. Social Capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lizardo, Omar. 2006. How cultural tastes shape personal networks. American Sociological Review 71:778–807.

Lizardo, Omar. 2016. Why “cultural matters” matter: Culture talk as the mobilization of cultural capital in interaction. Poetics 58:1–17.

Lusher, Dean, Johan Koskinen and Garry Robins (eds.). 2012. Exponential random graph models for social networks: theory, methods, and applications. 1. Aufl. Cambridge University Press.

Malacarne, Timothy. 2017. Rich friends, poor friends: Inter-socioeconomic status friendships in secondary school. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 3:237802311773699.

Marsden, Peter. 1990. Network data and measurement. Annual Review of Sociology 16:435–463.

Martin, John Levi. 2020. Comment on geodesic cycle length distributions in delusional and other social networks. Journal of Social Structure 21:77–93.

McPherson, Miller. 2004. A Blau space primer: Prolegomenon to an ecology of affiliation. Industrial and Corporate Change 13:263–280.

McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin and James M. Cook. 2001. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology 27:415–444.

Mood, C. 2010. Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review 26:67–82.

Morgan, Stephen L., and Aage B. Sorensen. 1999. Parental networks, social closure, and mathematics learning: A test of Coleman’s social capital explanation of school effects. American Sociological Review 64:661.

Mouw, Ted. 2006. Estimating the causal effect of social capital: A review of recent research. Annual Review of Sociology 32:79–102.

Paik, Anthony, and Kenneth Sanchagrin. 2013. Social isolation in America: An artifact. American Sociological Review 78:339–360.

Plenty, Stephanie, and Carina Mood. 2016. Money, peers and parents: Social and economic aspects of inequality in youth wellbeing. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45:1294–1308.

Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24:1–24.

Putnam, Robert D. 2007. E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian political studies 30:137–174.

Raabe, Isabel J., Zsófia Boda and Christoph Stadtfeld. 2019. The social pipeline: How friend influence and peer exposure widen the stem gender gap. Sociology of Education 92:105–123.

Roth, Tobias. 2014. Effects of social networks on finding an apprenticeship in the German vocational training system. European Societies 16:233–254.

Roth, Tobias. 2017. Interpersonal influences on educational expectations: New evidence for Germany. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 48:68–84.

Roth, Tobias. 2018. The influence of parents’ social capital on their children’s transition to vocational training in Germany. Social Networks 55:74–85.

Roth, Tobias, and Markus Weißmann. 2022. The role of parents’ native and migrant contacts on the labour market in the school-to-work transition of adolescents in Germany. European Sociological Review 38:707–724.

Shalizi, Cosma Rohilla, and Andrew C. Thomas. 2011. Homophily and contagion are generically confounded in observational social network studies. Sociological Methods & Research 40:211–239.

Small, Mario Luis. 2004. Villa Victoria: The transformation of social capital in a Boston barrio. University of Chicago Press.

Small, Mario Luis. 2009. Unanticipated gains: Origins of network inequality in everyday life. Oxford University Press.

Small, Mario Luis. 2017. Someone to talk to. Oxford University Press.