Abstract

Differences in educational goals between immigrants and the majority population have often been analysed at specific stages in their educational career. Little is known about longitudinal trajectories and the development of group differences over time. By applying common explanations (immigrant optimism, relative status maintenance, blocked opportunities, ethnic networks and information deficits), we derived specific hypotheses about the development of educational aspirations and expectations over time, focusing on families from Turkey. We drew upon data from the National Educational Panel Study to assess how aspirations and expectations for the highest school degree develop over the course of lower secondary education in Germany’s stratified school system. Applying a multi-actor perspective, we observed trajectories reported by students and their parents. First, we analysed the development of group differences. In line with prior research, we found higher aspirations and expectations for Turkish students and their parents at the beginning of lower secondary education in Germany once social background and achievement differences were controlled for. Origin gaps for students’ expectations and parents’ aspirations decreased over the course of lower secondary education. Second, intraindividual trajectories of aspirations and expectations revealed that parents of Turkish origin were more likely to experience downwards adaptations than majority parents, whereas students of Turkish origin were more likely to hold stable high aspirations and expectations than majority students.

Zusammenfassung

Unterschiede in den Bildungsaspirationen zwischen Personen mit Migrationshintergrund und der Mehrheitsbevölkerung wurden häufig an spezifischen Punkten der Bildungskarriere analysiert. Wenig ist jedoch über die Verläufe von Aspirationen und die Entwicklung ethnischer Unterschiede im Zeitverlauf bekannt. Unter Anwendung gängiger Erklärungsansätze (Immigrant optimism, relativer Statuserhalt, antizipierte Diskriminierung, ethnische Netzwerke und Informationsdefizite) leiten wir spezifische Hypothesen über die Entwicklung von Bildungsaspirationen und -erwartungen im Zeitverlauf ab und konzentrieren uns dabei auf Familien aus der Türkei. Wir greifen auf Daten des Nationalen Bildungspanels (NEPS) zurück, um zu untersuchen, wie sich die Aspirationen und Erwartungen für den höchsten Schulabschluss im Verlauf der Sekundarstufe I im stratifizierten Schulsystem Deutschlands entwickeln. Unter Anwendung einer Multi-Akteurs-Perspektive unterscheiden wir die von Schülerinnen und Schülern und ihren Eltern berichteten Aspirationsverläufe. Erstens analysieren wir die Entwicklung von Gruppenunterschieden. In Übereinstimmung mit früherer Forschung finden wir zu Beginn der Sekundarstufe I in Deutschland höhere Aspirationen und Erwartungen für türkische Schülerinnen und Schüler und ihre Eltern, wenn soziale Herkunft und Leistungsunterschiede kontrolliert werden. Die Herkunftsunterschiede für die Erwartungen der Schülerinnen und Schüler und die Aspirationen der Eltern nehmen im Verlauf der Sekundarstufe I ab. Zweitens zeigen die intra-individuellen Verläufe der Aspirationen und Erwartungen, dass türkischstämmige Eltern diese eher nach unten anpassen als Eltern der ethnischen Mehrheit, während türkischstämmige Schülerinnen und Schüler eine höhere Wahrscheinlichkeit stabil hoher Aspirationen und Erwartungen aufweisen als Schülerinnen und Schüler ohne Migrationshintergrund.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Educational achievement shapes the life course of individuals in modern societies. However, the educational achievement of certain immigrant groups tends to be lower than that of the majority population (e.g. Heath et al. 2008). Despite their lower educational achievement, immigrants’ educational aspirations and expectations often exceed those of their majority counterparts (e.g. Jackson 2012; Salikutluk 2016). This tendency has been documented for aspirations (also called idealistic aspirations; e.g. Dollmann 2017; Teney et al. 2013), which mainly reflect educational wishes, irrespective of constraints (e.g. Haller 1968), and for educational expectations (or realistic aspirations; e.g. Kao and Tienda 1995; Salikutluk 2016), where crucial restrictions, such as financial resources or academic performance, are considered (e.g. Haller 1968). For certain origin groups, high educational aspirations and expectations have been associated with more frequent transitions to higher school tracks once disadvantages due to social origin or educational performance were taken into account (e.g. Dollmann 2017; Heath and Brinbaum 2007; Jackson 2012). Under specific conditions, educational aspirations and expectations may thus partially compensate for immigrant disadvantages.

The high aspirations and expectations of different immigrant groups have mainly been documented in cross-sectional studies, often at central time points within the school career (e.g. Dollmann 2017; Relikowski et al. 2012; Teney et al. 2013). However, less is known about the development of immigrants’ aspirations and expectations over time. Both may evolve over the course of the educational career. In highly stratified school systems, aspirations and expectations might particularly develop during the period after the first educational transition into lower secondary education. Here, children are sorted into different ability tracks for the first time in their educational career. On the one hand, this transition is associated with new standards against which a child’s abilities are measured as well as with new information on potential career paths. Families might therefore (need to) update their evaluations of a student’s probability of success in a given school track or of the benefits of lower track credentials (Breen 1999). This might alter expectations over the course of lower secondary education. On the other hand, ability tracking brings about more homogeneous classroom contexts and social ties. For adolescent students, the educational norms and values of their peers become increasingly relevant (Raabe and Wölfer 2019). This might affect the aspirations of students over the course of lower secondary education.

Although both immigrant and majority families are exposed to such effects, they might shape aspirations and educational expectations to a different extent. Considering, for example, that families of certain origins tend to make more ambitious transitional decisions (e.g. Kristen and Dollmann 2009) and might thus be more likely to be confronted with “corrective” information on academic performance or educational pathways, immigrant families may more heavily adapt their educational expectations in the course of lower secondary education.

We contribute to the literature by studying the development of the aspirations and expectations of Turkish students and their parents and the majority population in Germany over the course of lower secondary education. Immigrants from Turkey make up one of the largest immigrant groups in Western Europe (Guveli et al. 2016) and have been shown to have particularly high educational ambitions (e.g. Salikutluk 2016), which in the second generation are higher than those of their peers in the majority population or immigrants of other origins (e.g. Stanat et al. 2010). First, we derived hypotheses on the aspirations and expectations of students and parents of Turkish origin and applied them to the development of educational aspirations and expectations. In a next step, we drew upon data from the National Educational Panel Study (Blossfeld and Roßbach 2019) to assess how the aspirations of Turkish students and their parents develop over the course of lower secondary education in Germany’s stratified school system.

2 Theoretical Considerations

2.1 Students of Turkish Origin in the German Educational Context—The Relevance of Country Context in this Study

In the German educational context, compared with their majority peers, immigrant students tend to be disadvantaged with regard to most educational outcomes (e.g. Diehl et al. 2016). However, there are differences between ethnic and immigrated groups, and students of Turkish descent are a particularly low-achieving group (e.g. Olczyk et al. 2016a). A large part of immigrants’ disadvantages can be traced to social origin (Heath and Brinbaum 2007). Disregarding their disadvantages due to social background and school performance, immigrants of Turkish origin in particular have been shown to make more ambitious transitional choices and to prefer the academic track (Kristen and Dollmann 2009; e.g. Kristen et al. 2008). These tendencies have often been assumed to be linked to the particularly high educational aspirations of this group (Kristen and Dollmann 2009). High educational ambitions have also been shown for Turkish immigrants in other country contexts (see, for instance, Teney et al. 2013 for evidence in the Netherlands), despite them often displaying a lower school performance. Against this backdrop, it is valuable to examine the factors that shape the resilient aspirations of Turkish families. The German context should be especially fruitful for an examination of the development of educational aspirations and expectations. Owing to the stratified school system (e.g. Kerckhoff 2001), there are two important transition points. First, children are allocated to different educational tracks after Grade 4 when primary education ends (after Grade 6 in three German states). Students enter either upper-level secondary school (“Gymnasium”), which is aimed at qualifying students for higher tertiary education, or intermediate-level (“Realschule”) or lower-level (“Hauptschule”) secondary schools, which generally prepare students for vocational education. There has also been a growing share of comprehensive schools that contain either all three tracks (“Integrierte Gesamtschule”) or only the intermediate and lower tracks (“Schularten mit mehreren Bildungsgängen”). The second important transition takes place at the end of lower secondary education into upper secondary education, where families can choose between entering the vocational training system, continuing schooling to qualify for higher education, or entering the labour market. In contrast to the first transition, adolescents themselves should be significantly involved in the decision-making process here.

In the period between the first and second transitions, children adapt to the realities within their respective school tracks and learn about different educational and occupational paths that are commonly associated with each track. In addition, school and classroom composition become more homogenous. This affects the aspirations of the peers to which students are exposed and which might contrast with the perceived peer aspirations during primary education. Families are thus exposed to several cues that may prompt them to reconsider their aspirations and expectations after the first educational transition; associated changes can then be observed for a comparatively long period afterwards until the second transition at the end of lower secondary school takes place.

2.2 Theorising the Formation of Educational Aspirations and Expectations—The Conceptual Framework

Scholars distinguish between aspirations and expectations (e.g. Haller 1968). The former are assumed to capture educational wishes or hopes detached from potential restrictions stemming from an individual’s educational realities. The latter, by contrast, are assumed to reflect educational expectations that take crucial constraints, such as financial limitations or academic performance, into account. Therefore, aspirations should be higher than expectations overall.

Empirically, it has been shown that aspirations vary by socioeconomic status and immigration background (Gölz and Wohlkinger 2019; Stocké 2013; Zimmermann 2019; cross-sectional, e.g. Chykina 2019), as do expectations (Salikutluk 2016; cross-sectional, e.g. Buchmann and Dalton 2002; Gölz and Wohlkinger 2019; longitudinal, e.g. Kleine et al. 2009; Lorenz et al. 2020). Two approaches are generally used to explain such differences, namely, the Wisconsin model of status attainment and rational choice theory. The Wisconsin model (e.g. Sewell et al. 1969, 1970) is mentioned primarily when aspirations are of interest. The main idea here is that individuals’ own educational wishes are shaped by the educational norms and values of their significant others, such as their immediate family, as well as by those of their friends, peers or wider social network. Individuals are assumed to either imitate the educational norms or behaviours of these significant others (called models) or adapt to the educational expectations that are communicated to them (by so-called definers) (e.g. Woelfel and Haller 1971, p. 76). With regard to expectations or realistic aspirations, scholars commonly refer to rational choice theory (Becker and Gresch 2016). It is assumed that individuals’ educational expectations are the result of an evaluation process in which the costs and benefits of different school tracks are weighed against each other. Potential benefits are thereby assumed to be conditional on the perceived probability of success (Erikson and Jonsson 1996). This implies that aspirations should be more stable over time than expectations owing to the changing educational realities shaping the latter (e.g. Andrew and Hauser 2011; Hoenig 2019, p. 88).

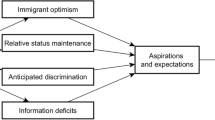

Furthermore, to explain group differences, especially between immigrated and majority populations, five main arguments are generally called upon. These are the notions of immigrant optimism (e.g. Kao and Tienda 1995), relative status maintenance (e.g. Engzell 2019), blocked opportunities (e.g. Pearce 2006), information deficits (e.g. Kao and Tienda 1998) and co-ethnic networks (e.g. Hao and Bonstead-Bruns 1998). The different theoretical arguments focusing on the effects of specific resources, values and norms could be linked to the general approaches of the Wisconsin model and rational choice theory. Group differences in aspirations and expectations, then, are the result of systematic differences in these resources, values and norms. We further argue that the theoretical arguments vary in their degree of time stability: Some of these arguments should be comparatively stable over students’ educational careers, whereas others might evolve and change—particularly after crucial educational transitions. Hence, they could be linked to the development of aspirations and expectations and might explain differences in aspirational and expectational trajectories between immigrated and majority families.

In the following, we describe how these factors are assumed to shape the aspirations and expectations of Turkish students and their parents in general and link them to the aspirational and expectational trajectories of Turkish families and majority families. We thereby derive predictions on how aspirations and expectations should evolve based on the different explanatory factors. Although we discuss which explanatory factors should be most relevant in light of the aspirational and expectational trajectories that we assess within the data, we cannot directly test each mechanism that may underlie the trajectories within our empirical analyses.

2.3 Factors Shaping Immigrants’ High Aspirations and Expectations and Their Development Over Time

In general, it is unlikely that any one factor affects only immigrants’ aspirations or only immigrants’ expectations. Rather, aspirations and expectations overlap—at least partially—and are empirically correlated (Buchmann and Dalton 2002, p. 101; Haller 1968, p. 485). Aspirations, for instance, can shape perceptions of the benefits that are associated with different school tracks in the evaluation of educational expectations. Consequently, factors that primarily shape aspirations should—in turn—also relate to expectations, and vice versa. To increase analytical precision, however, we will focus on the predominant effect that we expect. Thus, we will specify the mechanisms only for the aspirations or expectations that we assume to be particularly affected.

One argument highlights the role of immigrant optimism. The underlying assumption is that immigrants are positively selected in terms of motivation because they left their country of origin striving for a better life and upward mobility, particularly if they emigrated for economic reasons (e.g. Ogbu 1987). As first-generation immigrants are often unable to realise this goal themselves, they pass on this aim to the next generation, along with the idea that educational success is the “key to upward mobility” (Salikutluk 2016, p. 583). This also applies to a large proportion of the Turkish population in Germany. Most in this group immigrated as labour migrants, and therefore, one of their main migration motives should be a desire for upward mobility. For many first- and sometimes second-generation immigrants from Turkey, this goal cannot be fulfilled (e.g. Heath et al. 2008); thus, this aim is passed on to subsequent generations. Children therefore often perceive a strong obligation to realise their parents’ upward drive. The perceived importance of higher education for upward mobility should notably increase educational aspirations, particularly for first-generation parents. By transmission, these ideals then also shape students’ aspirations. Hence, we expect overall higher aspirations for Turkish families than for majority families. The desire for upward mobility represents a life goal that persists across generations for the Turkish group (Heath et al. 2008; Salikutluk 2016). We assume that—as a long-term goal—it is a relatively stable motivator that consistently fuels aspirations over the course of children’s educational careers. Consequently, we expect the aspirations of both Turkish parents and Turkish students to remain high over the course of lower secondary education.

A related line of thought pertains to the idea of relative status maintenance. It has been argued that immigrant parents may wish for their children to surpass not only their absolute but also their relative socioeconomic position (e.g. Engzell 2019). If, for instance, medium-level certificates place parents in the upper deciles of the social structure of their country of origin, children need to obtain higher educational degrees in destination countries where educational expansion has progressed further and faster to reach a similar status (see Becker and Gresch 2016, p. 87). Recent research suggests that nearly half of the immigrants of Turkish origin who entered Germany through labour migration held higher educational degrees than a large part of the remaining population (Spörlein et al. 2020). As educational expansion has progressed faster in Germany than in Turkey, immigrant children need to attain higher educational degrees within the German school system to obtain a social position that is at least as high as their parents’ relative status in the country of origin. Immigrant parents may thus have comparatively higher educational goals for their children. Such arguments primarily affect the perceived value of (higher) education, in turn shaping the aspirations mainly of immigrant parents and students. Here, too, we expect higher overall aspirations for Turkish parents and students than for majority families. As (relative) status maintenance also reflects a long-term or life goal, we also expect the aspirations of Turkish families to remain high over the course of lower secondary education. A potential limitation to this argument could be that this mechanism requires multiple additional assumptions that may be called into question: It implies that immigrated families can correctly specify their relative status position in both the country of origin and the country of destination and, at the same time, are aware of educational qualifications needed to achieve them in one context and the other.

Another argument relates to the anticipation of blocked opportunities due to discrimination. We elaborate on this for discrimination in different societal contexts because different contexts can lead to different predictions. First, it is assumed that immigrant families may fear discrimination in the labour market and in access to vocational education. This can bring about educational overcompensation and increased reliance on the protective effects of higher education (e.g. Jackson 2012; Sue and Okazaki 2009). Furthermore, as a discriminated group, Turkish families might also perceive negative events unrelated to discrimination as discriminatory based on prior negative experiences (Schaeffer 2019, p. 66). Consequently, beliefs in educational protection (through higher education) may shape the formation of educational expectations. Hence, according to this line of argumentation, we expect positive effects of anticipated discrimination in the labour market as well as higher educational expectations among Turkish parents and students than among majority families. Thus far, it is unclear how the perception of discrimination changes over time for immigrant families and how this relates to expectations. We assume that for Turkish families, the anticipation of discrimination may be present throughout the educational career. As they are exposed to actual discrimination (e.g. Kaas and Manger 2012) and negative attitudes in the German context (e.g. Steinbach 2004), these families might internalize their groups’ marginalized status in society, causing the anticipation of discrimination to vary little over time. In this case, anticipated discrimination would be a continuous motivator that increases the educational expectations of Turkish families over the whole course of lower secondary education. Empirical evidence on this subject, however, is scarce, perhaps not least because the opposite can also be the case: Anticipated discrimination may lead to resignation, demotivation or to the conscious rejection of norms and values of the majority, such as educational investments (Ogbu 1987, 1992; Skrobanek 2007), hence causing lower expectations of Turkish families than those of majority families. Under the condition that we assume a relatively continuous exposure to discrimination of Turkish students and parents, this negative effect could intensify over time and lead to a reduction of educational expectations in the course of lower secondary education.

Second, immigrants and their descendants may experience discrimination in school, which could, in turn, affect their assessment of success probabilities when forming educational expectations. Thus, we expect the negative effects of experienced discrimination and anticipate the educational expectations of Turkish students and parents to be lower than those of majority families. Experiences of discrimination within school could be singular events that affect different students at different times in their educational careers or continuous, recurring incidents that are associated with unfavourable attitudes of teachers or classmates. Experienced discrimination in school could thus be associated with fluctuating expectations (in the case of singular events) or with continuously decreasing expectations for Turkish families (in the case of recurring incidents) over the course of lower secondary education; therefore, here, we have no uniform prediction.

Furthermore, various arguments can be subsumed under information deficits (e.g. Kao and Tienda 1998; Salikutluk 2016). Immigrant families might be less familiar with the specificities of the German school system and the standards necessary to complete higher school tracks (Kao and Tienda 1998; Salikutluk 2016). They may thus inaccurately assess children’s probability of success in different tracks. In addition, although immigrant families tend to strive for prestigious positions in the labour market, they can be less aware that such positions may also be obtainable even through the vocational track or by attending universities of applied sciences in the German context (Kristen et al. 2008, p. 132). This is assumed to increase the expected benefits of higher-track credentials. Such arguments are primarily linked to the formation of educational expectations. Additionally, there are arguments related to the way in which information about educational credentials is processed: Vocational tracks and practical universities are less common in the Turkish context, and there are some indications that being assigned to such tracks is itself seen as less prestigious (Kristen et al. 2008, p. 132). Consequently, the educational expectations of Turkish parents and students may be higher than those of majority members upon entry into lower secondary education.

However, information deficits may not always persist to the same extent over the course of students’ educational careers. In highly stratified school systems, the period after students’ first meaningful transition, i.e. to lower secondary education, may be particularly relevant here. On the one hand, children are sorted into different ability tracks, which generates new standards and frames of reference against which a child’s performance is measured. Families thus receive new information that indicates whether their children may succeed in this track. On the other hand, towards the end of lower secondary education, students may be provided with external information on career possibilities and the educational tracks that lead to them. Although information on vocational education and its possibilities has been more prevalent in the lower school track, the federal employment agency recently increased efforts to provide information about vocational training and practical universities in higher school tracks as well. In line with Bayesian learning theory, families may update their evaluations of different educational credentials in light of the new information they receive (e.g. Breen 1999). Although German families on average have more information that they can consider about the school system before the first transition, Turkish families are more likely to gain new information through the track attendance that follows the first transition, which may change their expectations after the transition. Consequently, the educational expectations of Turkish families may change more than those of majority members.

These mechanisms should especially pertain to students and, to a lesser extent, parents of Turkish origin. Turkish children who enter the German school system are more exposed to interethnic frames of reference in the class context, receive frequent formal and informal feedback from teachers and tend to have better language abilities than their parents (e.g. Diehl and Schnell 2006). When expectations are unreasonably high, they are thus exposed to more and potentially corrective information, causing them to update their evaluations of their probability of success more rapidly and noticeably than their parents. Therefore, we expect that changes in the educational expectations of Turkish students should start earlier and be more defined than those of their parents.

Last, the high aspirations and expectations of immigrants have also been linked to embeddedness in co-ethnic networks (e.g. Hao and Bonstead-Bruns 1998; Wicht 2016). Ambitious educational goals can be widespread in ethnic communities, and community members function as role models that guide norms, values and behaviour. Such arguments tie in with models of status attainment, in which significant others provide relevant orientation and shape an individual’s preferences (Sewell et al. 1969). This should primarily affect the formation of aspirations. Insofar as educational goals are widespread within the Turkish community in Germany, we expect higher aspirations in Turkish families than in majority families.

Children’s social networks and significant others can change, especially after the first transition at the end of primary education. Aspirations are thus likely to change after this period. Turkish families, however, seem to be characterised by a high degree of solidarity (Merz et al. 2009), and adolescents can feel a strong obligation towards their parents (e.g. Vedder and Oortwijn 2009). In addition, Turkish immigrants have a greater tendency to enter co-ethnic friendships (e.g. Schacht et al. 2014), which should apply to students both inside and outside the school. These friendships can be characterised by similar educational goals, leading to the strengthening and maintenance of parental ideals. Hence, we assume that Turkish students’ aspirations might be less prone to change over the course of lower secondary education than those of the majority population and that they closely mirror their parents’ aspirations.

In addition to shaping aspirations, ethnic communities can provide resources conducive to educational success, which may increase the perceived probability of success in higher school tracks and, hence, shape the formation of expectations. In principle, resources that are available within ethnic networks may also change over the course of students’ educational careers. Individuals who are better endowed with valuable resources may, for instance, move in or out of ethnic enclaves, which may alter students’ probability of success and thus affect families’ expectations. However, such changes would be less systematic and affect different individuals at different points in time, foregoing uniform predictions. Table 1 summarises the central theoretical assumptions and predictions.

Based on these theoretical assumptions, we can formulate predictions on the initial and trajectorial differences between Turkish and majority families: We expect higher aspirations for Turkish families—owing to immigrant optimism, relative status maintenance, ethnic networks—as well as higher expectations—owing to anticipated discrimination in the labour market and information deficits—than those of majority families. During the course of lower secondary education, the majority of the suspected processes support the prediction that the aspiration gap between Turkish and majority families remains stable. Only experienced discrimination in school and information deficits suggest a decrease in the gap in educational expectations. It should be noted that these predictions are specified only for aspirations or expectations that we assume are particularly affected. Furthermore, it should be noted that different mechanisms may be at work simultaneously, and they do not have to take place in isolation from each other; interrelations are plausible.

3 Methods

In the following sections, we present the steps we took to empirically examine the development of differences in the aspirations and educational expectations of Turkish and majority families. We then describe the trajectories of these differences for students as well as their parents.

3.1 Data

3.1.1 The National Educational Panel Study

To assess the development of inequalities in aspirations and expectations in German lower secondary education, we relied on the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), a large-scale multicohort panel study (Blossfeld and Roßbach 2019). Thus far, the NEPS comprises the only dataset within the German context containing repeated measurements of educational aspirations and expectations for the whole lower secondary education stage. Using Starting Cohort 3 (NEPS-SC3),Footnote 1 we followed students from Grade 5, after the transition to lower secondary education in Germany, up to Grade 9, before students from lower tracks leave general schooling and enter vocational education.

3.1.2 Sample Selection

As educational prospects are not fully comparable, we excluded students from special needs institutions (“Förderschulen”). For reasons of longitudinal comparability, we also excluded students who were sampled at a later point in Grade 7. As we focus on the differences between majority students and those of Turkish origin, we disregarded students from other immigrant origins. This left us with a total sample of 3986 students and 19,930 student-years.

3.1.3 Missing Data

As complete information on aspirational trajectories was highly selective with regard to our central model variables (Table A.6 in the Appendix), we imputed missing data with fully conditional specifications to obtain a balanced panel. To take serial correlation into account, we imputed the data in wide format, utilising earlier and later measurements where possible for the imputation of time-varying variables (Young and Johnson 2015). The proportion of missing information was relatively large for some variables (Table 2). We therefore generated 100 imputed datasets (White et al. 2011). As multiple so-called auxiliary variables that correlated with both data missingness and the level of aspiration were available, we included imputations of the outcome variables in our analyses (Sullivan et al. 2017).Footnote 2 Furthermore, we imputed data separately by origin group to account for expected origin-specific processes in the formation of aspirations as well as potential differences in factors associated with non-response and attrition. The imputations were combined using Rubin’s rules (Rubin 1987).

3.2 Variables

In the following, we describe the operationalisation of all considered constructs. Table 2 presents the associated variable characteristics and distributions separately for Turkish and majority respondents.

3.2.1 Outcome: Educational Aspirations and Expectations

We examined the aspirations and expectations of students and their parents. Both were asked about the school degree that they wished to obtain, irrespective of the current school situation (aspirations or idealistic aspirations), either for themselves (students) or their child (parents); they were also asked about the degree that they realistically believe they can obtain, given all current restrictions (expectations or realistic aspirations)—again for themselves (students) or their child (parents). As aspirations and expectations for no degree or the lowest degree were rare (between 1.4% for parents’ aspirations in Year 5 and 12.1% for students’ expectations in Year 9), we merged them with those for intermediate degrees and distinguished only between the general higher education entrance qualification (“Abitur”) and lower degrees.Footnote 3 Aspirations and expectations were measured yearly from Grade 5 to 9 for students and Grade 6 to 9 for parents.

3.2.2 Immigrant Origin

Immigrant origin was operationalised through the country of birth of students, parents and grandparents (Olczyk et al. 2016b). We differentiated between majority students and students of Turkish origin. We restricted the latter group to students from the first to the 2.75th migration generation; thus, at least one parent was born in Turkey. Students from the third generation (at least one grandparent born abroad) were excluded from the main analyses. Information on country of birth was obtained upon panel entry.

3.2.3 Controls

We considered the school type the students currently attend based on a preconstructed variable (see Bayer et al. 2014) as well as retrospective student reports. Only a very low number of students of Turkish origin were enrolled in combined lower and intermediate multitrack schools in Grade 5. Thus, we combined low/intermediate multitrack schools with lower-level secondary schools (“Hauptschule”). Moreover, we included the yearly grade point averages based on grades in maths and German.Footnote 4 Last, we also controlled for parents’ highest International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI-2008), parents’ highest education based on the International Standard Classification of Education, and students’ gender.

3.3 Analytical Strategy

Adopting a holistic longitudinal perspective, we first described how the educational aspirations of students and their parents developed over the course of lower secondary education on a population level. We conducted “state-probability analyses” (Brüderl et al. 2019) based on logistic regression models to estimate the predicted probability curves of high degree aspirations and expectations over the course of lower secondary education. By introducing the interaction terms of origin and year dummies, we allowed for non-linear group-specific aspiration and expectation trajectories. Without control variables, this model reflects the observed development of aspirations and expectations. To identify the development of aspirations depending on immigrant origin, we controlled for social background, performance in terms of grades and school type in the next step. In this way, we assessed the aspirational and expectational differences between students of Turkish origin and majority students net of social background and performance differences in analogy to immigration-specific secondary effects.Footnote 5 In addition, we controlled for students’ gender, as aspirations vary by gender.

We estimated the predicted probabilities of high degree aspirations and expectations and their 95% confidence intervals (based on student cluster robust standard errors). State-probability analyses indicated how origin-specific levels of aspiration develop over the course of lower secondary education. However, they did not allow for clear conclusions about the amount of intraindividual variability. For example, a population-level decrease of 10 percentage points may be caused by the fact that 10% of the students switched from high to low aspirations, whereas all other students maintained their initial aspirations. However, it could just as well be that 50% decreased their initially high aspirations, whereas 10% maintained their initial aspirations and 40% developed high aspirations. Therefore, we provided additional descriptive evidence on variability for majority students and students of Turkish origin. We constructed four simplified patterns of individual aspiration trajectories between Grade 5 (for parents: Grade 6) and Grade 9: stable low, downward change, upward change and stable high.Footnote 6 We reported the distributions of the patterns for parents’ and students’ aspirations and expectations. We further differentiated our analyses by initial school type to put the trajectory patterns into context. To estimate differences based on immigrant background, we account for social background and performance differences in a similar manner to the first analysis step.Footnote 7

4 Results

4.1 Development of Origin Gaps

First, we examined the development of aspirations and expectations at the group level. Figure 1 shows the observed aspirations and expectations of students and parents of Turkish origin and those of majority students and parents in the course of lower secondary education. Despite their lower social background and grades compared with majority families, Turkish families showed similar or higher levels of aspirations and expectations at the beginning of lower secondary education. During lower secondary education, aspirations and expectations slightly declined by up to 10 percentage points in the majority group. For Turkish parents’ aspirations and Turkish students’ expectations, the decline was even more pronounced (Fig. 1, top left and bottom right).

Observed probabilities of high aspirations and expectations for students and parents of Turkish origin and those of majority students and parents (without controls for social background and performance). Notes: Observed probabilities and 95% confidence intervals based on logistic regressions without control variables; N = 3986. (Source: Own calculations based on NEPS-SC3)

Figure 2 shows the development net of achievement and social background differences.

Predicted probabilities of high aspirations and expectations for students and parents of Turkish origin and those of majority students and parents (net of social background and performance). Notes: Predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals based on logistic regressions controlling for gender, parents’ highest ISEI, parents’ highest school degree, school type, and grade point average, including interactions of immigrant background with parents’ highest ISEI, school type and grade point average. For full models and exact values, see the online appendix (Tables A.2 and A.3). N = 3986. (Source: Own calculations based on NEPS-SC3)

Our results confirmed known positive effects of Turkish origin for both educational aspirations and expectations at the beginning of lower secondary education. Hence, students and parents of Turkish origin had a significantly higher overall probability of striving for “Abitur” than their majority counterparts, and the probabilities were generally higher for aspirations than for expectations. Over the course of lower secondary education, aspirations and expectations generally decreased for immigrant and majority families. However, the patterns for aspirations and expectations differed slightly (see Fig. 2).

The gaps between minority and majority parents’ aspirations (Fig. 2, top left) decreased between Grade 6 and Grade 9 (from 26.9 to 8.3 percentage points; Chi-squared = 11.6, p < 0.01), but the origin gaps remained stable for students’ aspirations (from 13.4 to 11.4 percentage points; Chi-squared = 0.5, p = 0.50). In addition, Turkish students seemed to adjust their aspirations slightly later than their parents.

Parents’ expectations (Fig. 2, top right) fluctuated slightly, and the corresponding origin gap decreased only slightly (from 14.3 to 7.6 percentage points; Chi-squared = 1.5, p = 0.22). Students’ expectations decreased over the course of lower secondary education, with a sharper decline for students of Turkish origin (by 17.3 percentage points) than for majority students (7.6 percentage points). Origin differences declined significantly (from 15.4 to 5.6 percentage points; Chi-squared = 8.6, p < 0.01).

In general, Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate how group differences in aspirational and expectational trajectories developed during secondary education. As the development of group differences did not give us any indications of intraindividual trajectories, in the next section, we analysed the changes in aspirations and expectations for students and parents separately.

4.2 Intraindividual Changes in Aspirations and Expectations

Figure 3 shows how aspirations and expectations changed between the first and last measurement during lower secondary education for students and parents of Turkish origin and for the majority population. Furthermore, we showed the results not only for the whole group but also based on the school type attended in Year 5. Each bar in Fig. 3 presents the simplified aspirational and expectational trajectories between Grade 5 (or 6, for parents) and Grade 9. We distinguished the following patterns:

-

1.

Stable low: Aspirations and expectations were low at the beginning and end of secondary school;

-

2.

Downward change: Aspirations and expectations were high at the beginning of the secondary level and were adjusted downwards in the course of secondary school.

-

3.

Upward change: Aspirations and expectations were low at the beginning and high at the end of lower secondary school.

-

4.

Stable high: Ambitions were high at the start and at the end of secondary school.

Observed patterns of aspirational and expectational trajectories: comparisons between Grade 5 (Grade 6 for parents) and Grade 9 by initial school type (without controls for social background and performance). Notes: Observed patterns based on multinomial logistic regressions without controls. N = 3986. Bar labels show percentages ≥ 5%. Significance levels of probability differences between Turkish origin and majority: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Low lower-level secondary and multitrack low/intermediate schools, Int intermediate-level secondary schools, Comp comprehensive schools, Upper upper-level secondary schools, All all school types. (Source: Own calculations based on NEPS-SC3)

With regard to the majority population, both aspirations and expectations were generally stably low for the lower school type, whereas they were generally stably high for the academic type (Fig. 3a, c, e, g). We observed slightly more upward and downward adjustment of ambitions in the intermediate school type and in comprehensive schools than in the lower and upper secondary school types. These patterns were similar for parents and children in the majority population.

The aspirations and expectations of Turkish families revealed a different picture (Fig. 3b, d, f, h). The stably low pattern occurred less often in lower and intermediate schools as well as in comprehensive schools. This was particularly evident for parental aspirations (Fig. 3a, b). In the lower track, only slightly more than 20% of the parents had consistently low aspirations, whereas this applied to almost 80% of native parents. On the other hand, we also observed that the proportion of those who had stable high aspirations or expectations was lower in the Turkish group. The proportions of those who had to adjust their aspirations and expectations downwards were more pronounced among Turkish parents and students than in the majority population.

Furthermore, parents and students of Turkish origin more often reported upward changes and were characterised by less intraindividual stability. In addition, although aspirations and expectations here were more often stably high in lower tracks of secondary education, they were less often stably high in higher school tracks.

Figure 4 shows the patterns of individual change net of social background and performance. This captured origin differences that would exist if there were no group differences in social background and performance. The probability of experiencing downward trajectories was significantly increased for Turkish parents but not for Turkish students. Immigration-specific differences in upward trajectories could only be observed with regard to parents’ expectations. Although the probability of stable high aspirations and expectations did not increase for Turkish parents compared with the majority, Turkish students were more likely to hold stably high aspirations and expectations than majority students. Finally, students and parents of Turkish origin had a lower likelihood of stably low aspirations and expectations.

Predicted patterns of aspirational and expectational trajectories: comparisons between Grade 5 (Grade 6 for parents) and Grade 9 (net of social background and performance). Notes: Predicted probabilities of patterns based on multinomial logistic regressions with controls (gender, parents’ highest ISEI, parents’ highest school degree, school type in first and last grade, and grade point average in first and last grade, including interactions of immigrant background with parents’ highest ISEI, school type, and grade point averages). For full models and exact values, see the online appendix (Tables A.4 and A.5). N = 3986. Bar labels show percentages ≥ 5%. Significance levels of probability differences between Turkish origin and majority: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (Source: Own calculations based on NEPS-SC3)

4.3 Robustness of the Main Results

To check the robustness and generalisability of our results, we performed several additional analyses (Figs. A.2 and A.3 in the online appendix). We first carried out our central analyses on the aspirational and expectational trajectories of students who may be more likely to adjust their aspirations; namely, students in low and intermediate tracks. Furthermore, we also reconducted our analyses while considering only Turkish origin students of the second generation (generation 2.0, with both parents born in Turkey) and while including the third generation (generation 3.0–3.75); we also examined an alternative threshold for high degree aspirations. Although patterns varied to a certain extent, the general tendencies remained comparable.

5 Summary and Discussion

Previous research has focused primarily on why aspirations and expectations often differ between immigrants and the majority population at specific stages in their educational career. Much less is known about aspirational and expectational trajectories and the development of group differences. By applying common explanations, we derived assumptions about the development of aspirations and expectations, focusing on Turkish families. In general, we expected that aspirations and expectations would be higher and more stable in Turkish families than in majority families. If there are changes in the gap between Turkish and majority families, then they should be observable primarily in the expectational trajectories and less in the aspirational. The theoretical considerations suggested that a change in educational expectations among Turkish parents and students might take place, particularly because of a reduction in information deficits in the course of lower secondary education.

In line with our assumptions and prior research, we found higher aspirations and expectations for Turkish families at the beginning of lower secondary education in Germany once social background- and performance-based disadvantages were taken into account. For Turkish and majority students, aspirations and expectations continuously decreased over the course of lower secondary education. The similar patterns of the two groups may be due to the fact that in Germany’s stratified school system, the demands and wishes that students are exposed to are very similar within the individual school types and affect students of different origins in the same way. Hence, in relatively homogeneous contexts, there should be few and similar changes due to processes of social influence (see for example Buchmann and Dalton 2002; Lorenz et al. 2020 for results pointing in this direction). However, although the expectation gap between the two groups shrunk, differences remained for students’ aspirations at the end of this educational stage. The consistently higher aspirations of Turkish students might reflect time-stable goals that are associated with immigrant optimism and relative status maintenance. As suggested by prior research (Salikutluk 2016), Turkish students seem to strongly internalize their parents’ striving for upward mobility and—in our case—follow this goal throughout the lower secondary education stage.

Turkish parents, by contrast, exhibited a sharp decline in educational aspirations, and the gap with majority members decreased over the course of lower secondary education. Their educational expectations and the associated gap with majority members, however, decreased only slightly. Hence, although we assumed that reduced information deficits and anticipated and perceived discrimination shape parents’ expectations and that stable factors such as immigrant optimism and relative status maintenance are associated with aspirations, empirical patterns suggested the opposite. A potential explanation could be related to the level of aspirations and expectations that all parents had at entry into this educational stage. The aspirations of Turkish parents were extremely high, with nearly all aspiring to higher education entry certificates. Considering that, on average, majority students outperformed their Turkish counterparts, the aspirations of Turkish parents may thus be more “off” at the beginning of this educational stage and have more room to change and adapt to educational realities. The educational expectations of Turkish parents as well as the expectations and aspirations of majority parents started at a lower level, with less room for downward changes. In general, this finding also illustrates that educational aspirations can be more affected by adaptations than commonly assumed. In line with recent research, which showed the negative consequences of large discrepancies between educational aspirations and expectations (Boxer et al. 2011; Greenaway et al. 2015; Schotte et al. 2017), the adjustment of educational goals may be a protective mechanism for families.

A comparison of the intraindividual patterns of aspirations and expectations in Grades 5 (or 6) and 9 revealed that Turkish parents experienced downward adjustments more often, whereas Turkish students held stably high aspirations and expectations more often. These findings are very important, as they showed the highly dynamic nature of aspirations and expectations in Turkish families. In particular, the strong need to adjust aspirations and expectations downwards became obvious. This trend will continue in the further course of education considering the high number of Turkish parents who still had consistently high aspirations, even though their children were assigned only to lower tracks. In majority families, it actually seemed to be more the case that the educational decision, once made, was not questioned further and that educational aspirations and expectations were very stable, at least in the lower track and academic track of the German educational system.

The reported patterns indicated a two-pronged strategy: On the one hand, for children who show high educational goals despite poorer conditions, extra support opportunities could be offered to promote the realisation of these educational goals. On the other hand, if it is unrealistic to achieve educational goals, target programs should provide information about alternative pathways to avoid high drop-out rates or “optimism traps” (Tjaden and Hunkler 2017). Such programs may help to avoid long-term resignation and demotivation in the education system.

Overall, the much stronger adjustments in educational aspirations and expectations among Turkish adolescents and parents after the transition to lower secondary education can be understood as an indication that immigrant families find it much more difficult to assess the consequences of this early educational decision. This aspect should be considered in the discussion about the strong structuring and early tracking in the German education system.

Future research should go a step further and study the mechanisms underlying differences in aspirational and expectational trajectories by considering the degree of time stability of the explanatory factors. Furthermore, the consideration of the developments in different school tracks should be carried out, and the arguments put forward should be specified accordingly to be able to pick up on differential patterns depending on the type of school attended. Aspirational and expectational trajectories and the reasons behind them may also vary between different immigrant groups; for instance, students originating from the former Soviet Union have been shown to have aspirations that differ from those of their Turkish peers at around Grade 9 (e.g. Salikutluk 2016). Hence, future research should examine the development of aspirations and expectations of other immigrant groups by adapting the theoretical arguments to their specific situation. Finally, there may be cross-country differences in how educational aspirations and expectations develop, particularly when school systems are more egalitarian and less stratified, as in most Scandinavian countries.

Finally, this study also has some limitations. First, our measurement of aspirations and expectations is limited to whether the highest school degree (“Abitur”) is aspired to or expected. In doing so, we had to ignore differences between degree levels below the Abitur owing to low case numbers. Furthermore, we were not able to measure individual uncertainties in the strength of aspirations as well as possible fine-grained differences, e.g. in the degree of ideality or the likelihood of obtaining the different school degrees (Stocké 53,54,a, b). Second, the proportions of missing values are relatively high in late panel waves, especially in the parent surveys. We attempted to minimise possible bias due to selective panel attrition by multiply imputing the data while considering the longitudinal structure of the data, possible origin-specific dropout mechanisms and auxiliary variables that are associated with the level of aspirations and/or the probability of attrition. Nevertheless, unobserved systematic bias cannot be completely ruled out.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the literature on immigrant aspirations and expectations in several ways. Taking a longitudinal approach, this paper demonstrated that the educational aspirations and educational expectations of immigrant families evolved over time and that these developments differed—in part—from those of the majority population. We thereby assessed the educational aspirations and expectations of the largest immigrant group in Germany for a period that is commonly associated with changes in performance standards and peer composition in stratified school systems. Overall, our study highlights the need to move beyond static conceptualisations of immigrant aspirations and their underlying motives. It also calls upon future research to examine such processes more closely in general and for subgroups in particular.

Notes

Starting Cohort 3 (10.0.0), https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC3:10.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data were collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Since 2014, the NEPS has been carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg, in cooperation with a nationwide network.

As auxiliaries, we used the first and the last measurement of a series of student variables (school satisfaction, subjective health, friends’ aspirations, perceived parental aspirations, self-esteem, books in household, success probability and benefits of intermediate and high degrees) and parent variables (books in household, child health) as well as birth month, immigrant generation category (1.0–1.5, 2.0, 2.25–2.75, 3.0–3.75), and grades at the end of primary school.

In panel waves one to three (Grades 5 to 7), four degrees were distinguished (no degree, degrees from “Hauptschule”, degrees from “Realschule” and “Abitur”). After the third panel wave, additional degrees were distinguished for the “Hauptschule” (“qualifizierender Hauptschulabschluss”, “erweiterter Hauptschulabschluss”) and for restricted higher education entrance qualifications (“Fachhochschulreife”, “fachgebundene Hochschulreife”), which we categorized as lower degrees. As a robustness check, we also considered restricted higher education entrance qualifications in the definition of high aspirations, which yielded very similar results (online appendix Fig. A.2 and Fig. A.3, b, g, l, q).

Grades from one school year were collected in the following year. We opted for end-of-year grades (which partially comprise the results of school tests taken after the measurement of aspirations) rather than last year’s grades as achievement measures because they provided a more valid assessment of achievement with respect to the actual school track. This introduced no serious problems of reverse causality, as the causal effects of expectations on achievement have been shown to be minuscule (Dochow and Neumeyer 2021).

Previous research has shown that immigration-specific secondary effects are particularly pronounced among students with low social background and among students with low performance (Dollmann 2017; Relikowski et al. 2012; Salikutluk 2016) or, put differently, that minority students’ aspirations and expectations are less associated with social background and performance. Although such interactions are not the focus of this paper, we accounted for them in the analyses to correctly estimate differences depending on immigrant origin across the distributions of socioeconomic status and achievement. The interactions are illustrated in the Appendix (Appendix, Fig. A.1).

Note that the patterns are simplifications of the trajectories between Grade 5/6 and Grade 9 without considering what happens in the years in between (Grade 6/7 to Grade 8). In fact, patterns we described as stable might include short-term deviations (e.g. low high low low), and patterns we described as change might include multiple changes (e.g. low high low high). Together, these fluctuating patterns have been found for about one fifth of lower secondary students (Dochow and Neumeyer 2021).

We did not further differentiate by initial school type in this step of the analysis because individual trajectory patterns rarely occur in specific school types and, therefore, it was not possible to estimate their frequency while accounting for control variables.

References

Andrew, Megan, and Robert M. Hauser. 2011. Adoption? Adaptation? Evaluating the formation of educational expectations. Social Forces 90:497–520.

Bayer, Michael, Frank Goßmann and Daniel Bela. 2014. NEPS technical report. Generated school type variable t723080_g1 in NEPS-SUFs of starting cohorts 3 and 4. NEPS working paper no. 46. Bamberg: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, National Educational Panel Study.

Becker, Birgit, and Cornelia Gresch. 2016. Bildungsaspirationen in Familien mit Migrationshintergrund. In Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf: Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten, eds. Claudia Diehl, Christian Hunkler and Cornelia Kristen, 73–115. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, and Hans-Günther Roßbach (eds.). 2019. Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Boxer, Paul, Sara E. Goldstein, Tahlia DeLorenzo, Sarah Savoy and Ignacio Mercado. 2011. Educational aspiration–expectation discrepancies: Relation to socioeconomic and academic risk-related factors. Journal of Adolescence 34:609–617.

Breen, Richard. 1999. Beliefs, rational choice and baysian learning. Rationality and Society 11:463–479.

Brüderl, Josef, Fabian Kratz and Gerrit Bauer. 2019. Life course research with panel data: An analysis of the reproduction of social inequality. Advances in Life Course Research 41:100247.

Buchmann, Claudia, and Ben Dalton. 2002. Interpersonal influences and educational aspirations in 12 countries: The importance of institutional context. Sociology of Education 75:99–122.

Chykina, Volha. 2019. Educational expectations of immigrant students: Does tracking matter? Sociological Perspectives 62:366–382.

Diehl, Claudia, and Rainer Schnell. 2006. “Reactive ethnicity” or “assimilation”? Statements, arguments, and first empirical evidence for labor migrants in Germany. International Migration Review 40:786–816.

Diehl, Claudia, Christian Hunkler and Cornelia Kristen. 2016. Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf. Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Dochow, Stephan, and Sebastian Neumeyer. 2021. An investigation of the causal effect of educational expectations on school performance. Behavioral consequences, time-stable confounding, or reciprocal causality? Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 71:100579.

Dollmann, Jörg. 2017. Positive choices for all? SES- and gender-specific premia of immigrants at educational transitions. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 49:20–31.

Engzell, Per. 2019. Aspiration squeeze: The struggle of children to positively selected immigrants. Sociology of Education 92:83–103.

Erikson, Robert, and Jan O. Jonsson. 1996. Can education be equalized? The Swedish case in comparative perspective. Stockholm: Westview Press.

Gölz, Nicole, and Florian Wohlkinger. 2019. Determinants of students’ idealistic and realistic educational aspirations in elementary school. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 22:1397–1431.

Greenaway, Katharine H, Margaret Frye and Tegan Cruwys. 2015. When aspirations exceed expectations: Quixotic hope increases depression among students. PLoS ONE 10:1–17.

Guveli, Ayse, Harry B. G. Ganzeboom, Lucinda Platt, Bernhard Nauck, Helen Baykara-Krumme, Şebnem Eroğlu, Sait Bayrakdar, Efe K. Sözeri, Niels Spierings and Sebnem Eroglu-Hawskworth. 2016. Intergenerational consequences of migration. Socio-economic, family and cultural patterns of stability and change in Turkey and Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haller, Franz J. 1968. On the concept of aspiration. Rural Sociology 33:484–487.

Hao, Lingxin, and Melissa Bonstead-Bruns. 1998. Parent-child differences in educational expectations and the academic achievement of immigrant and native students. Sociology of Education 71:175–198.

Heath, Anthony, and Yaël Brinbaum. 2007. Guest editorial. Explaining ethnic inequalities in educational attainment. Ethnicities 7:291–304.

Heath, Anthony F., Catherine Rothon and Elina Kilpi. 2008. The second generation in Western Europe: Education, unemployment, and occupational attainment. Annual Review of Sociology 34:211–235.

Hoenig, Kerstin. 2019. Soziales Kapital und Bildungserfolg. Differentielle Renditen im Bildungsverlauf. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Jackson, Michelle. 2012. Bold choices: How ethnic inequalities in educational attainment are suppressed. Oxford Review of Education 38:189–208.

Kaas, Leo, and Christian Manger. 2012. Ethnic discrimination in Germany’s labour market: A field experiment. German Economic Review 13:1–20.

Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1995. Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly 76:1–19.

Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1998. Educational aspirations of minority youth. American Journal of Education 106:349–384.

Kerckhoff, Alan C. 2001. Education and social stratification processes in comparative perspective. Sociology of Education 74:3–18.

Kleine, Lydia, Wiebke Paulus and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 2009. Die Formation elterlicher Bildungsentscheidungen beim Übergang von der Grundschule in die Sekundarstufe I. In Bildungsentscheidungen. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft Sonderheft, eds. Jürgen Baumert, Kai Maaz and Ulrich Trautwein, 103–125. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kristen, Cornelia, and Jörg Dollmann. 2009. Sekundäre Effekte der ethnischen Herkunft: Kinder aus türkischen Familien am ersten Bildungsübergang. In Bildungsentscheidungen, eds. Jürgen Baumert, Kai Maaz and Ulrich Trautwein, 205–229. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kristen, Cornelia, David Reimer and Irena Kogan. 2008. Higher education entry of turkish immigrant youth in Germany. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49:127–151.

Lorenz, Georg, Zsófia Boda, Zerrin Salikutluk and Malte Jansen. 2020. Social influence or selection? Peer effects on the development of adolescents’ educational expectations in Germany. British Journal of Sociology of Education 41:643–669.

Merz, Eva-Maria, Ezgi Özeke-Kocabas, Frans J. Oort and Carlo Schuengel. 2009. Intergenerational family solidarity: Value differences between immigrant groups and generations. Journal of Family Psychology 23:291–300.

Ogbu, John U. 1987. Variability in minority school performance: A problem in search of an explanation. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 18:312–334.

Ogbu, John U. 1992. Understanding cultural diversity and learning. Educational Researcher 21:5–14.

Olczyk, Melanie, Julian Seuring, Gisela Will and Sabine Zinn. 2016a. Migranten und ihre Nachkommen im deutschen Bildungssystem: Ein aktueller Überblick. In Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf. Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten, eds. Claudia Diehl, Christian Hunkler and Cornelia Kristen, 33–70. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Olczyk, Melanie, Gisela Will and Cornelia Kristen. 2016b. Immigrants in the NEPS. Identifying generation status and group of origin. NEPS working paper no. 4. Bamberg: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, National Educational Panel Study.

Pearce, Richard R. 2006. Effects of cultural and social structural factors on the achievement of white and Chinese American students at school transition points. American Educational Research Journal 43:75–101.

Raabe, Isabel J., and Ralf Wölfer. 2019. What is going on around you: Peer milieus and educational aspirations. European Sociological Review 35:1–14.

Relikowski, Ilona, Erbil Yilmaz and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 2012. Wie lassen sich die hohen Bildungsaspirationen von Migranten erklären? Eine Mixed-methods-Studie zur Rolle von strukturellen Aufstiegschancen und individueller Bildungserfahrung. In Soziologische Bildungsforschung, eds. Rolf Becker and Heike Solga, 111–136. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Rubin, Donald B. 1987. The calculation of posterior distributions by data augmentation: comment: a noniterative sampling/importance resampling alternative to the data augmentation algorithm for creating a few imputations when fractions of missing information are modest: the SIR algorithm. Journal of the American Statistical Association 82:543–546.

Salikutluk, Zerrin. 2016. Why do immigrant students aim high? Explaining the aspiration–achievement paradox of immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review 32:581–592.

Schacht, Diana, Cornelia Kristen and Ingrid Tucci. 2014. Interethnische Freundschaften in Deutschland. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66:445–458.

Schaeffer, Merlin. 2019. Social mobility and perceived discrimination: Adding an intergenerational perspective. European Sociological Review 35:65–80.

Schotte, Kristin, Oliver Winkler und Aileen Edele. 2017. Die Schulzufriedenheit von Heranwachsenden mit türkischem und ohne Zuwanderungshintergrund: Welche Rolle spielt die Kluft zwischen idealistischen und realistischen Bildungsaspirationen? Empirische Pädagogik 31:432–459.

Sewell, William H., Archibald O. Haller and Alejandro Portes. 1969. The educational and early occupational attainment process. American Sociological Review 34:82–92.

Sewell, William H., Archibald O. Haller and George W. Ohlendorf. 1970. The educational and early occupational status attainment process: Replication and revision. American Sociological Review 35:1014–1027.

Skrobanek, Jan. 2007. Wahrgenommene Diskriminierung und (Re)Ethnisierung bei Jugendlichen mit türkischem Migrationshintergrund und jungen Aussiedlern. Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation 27:265–284.

Spörlein, Christoph, Cornelia Kristen, Regine Schmidt and Jörg Welker. 2020. Selectivity profiles of recently arrived refugees and labour migrants in Germany. Soziale Welt 71:54–89.

Stanat, Petra, Michael Segeritz and Gayle Christensen. 2010. Schulbezogene Motivation und Aspiration von Schülerinnen und Schülern mit Migrationshintergrund. In Schulische Lerngelegenheiten und Kompetenzentwicklung: Festschrift für Jürgen Baumert, eds. Wilfried Bos, Eckhard Klieme and Olaf Köller, 31–57. Münster: Waxmann.

Steinbach, Anja. 2004. Soziale Distanz. Ethnische Grenzziehung und die Eingliederung von Zuwanderern in Deutschland. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Stocké, Volker. 2013. Bildungsaspirationen, soziale Netzwerke und Rationalität. In Bildungskontexte. Strukturelle Voraussetzungen und Ursachen ungleicher Bildungschancen, eds. Rolf Becker and Alexander Schulze, 269–298. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Stocké, Volker. 2014a. Idealistische Bildungsaspirationen. Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis197.

Stocké, Volker. 2014b. Realistische Bildungsaspiration. Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis216.

Sue, Stanley, and Sumie Okazaki. 2009. Asian-American educational achievements: A phenomenon in search of an explanation. Asian American Journal of Psychology S:45–55.

Sullivan, Thomas R., Katherine J. Lee, Philip Ryan and Amy B. Salter. 2017. Multiple imputation for handling missing outcome data when estimating the relative risk. BMC Medical Research Methodology 17:134.

Teney, Celine, Perrine Devleeshouwer and Laurie Hanquinet. 2013. Educational aspirations among ethnic minority youth in Brussels: Does the perception of ethnic discrimination in the labour market matter? A mixed-method approach. Ethnicities 13:584–606.

Tjaden, Jasper D., and Christian Hunkler. 2017. The optimism trap: Migrants’ educational choices in stratified education systems. Social Science Research 67:213–228.

Vedder, Paul, and Michiel Oortwijn. 2009. Adolescents’ obligations toward their families: Intergenerational discrepancies and well-being in three ethnic groups in the Netherlands. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 40:699–717.

White, Ian R., Patrick Royston and Angela M. Wood. 2011. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine 30:377–399.

Wicht, Alexandra. 2016. Occupational aspirations and ethnic school segregation: Social contagion effects among native German and immigrant youths. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42:1825–1845.

Woelfel, Joseph, and Archibald O. Haller. 1971. Significant others, the self-reflexive act and the attitude formation process. American Sociological Review 36:74–87.

Young, Rebekah, and David R. Johnson. 2015. Handling missing values in longitudinal panel data with multiple imputation. Journal of Marriage and the Family 77:277–294.

Zimmermann, Thomas. 2019. Social influence or rational choice? Two models and their contribution to explaining class differentials in student educational aspirations. European Sociological Review 36:65–81.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project numbers 335816694 and 390731161. The DFG was not involved in decisions regarding the research process or the publication.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Online Appendix: https://kzfss.uni-koeln.de/sites/kzfss/pdf/Neumeyer_et_al.pdf

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neumeyer, S., Olczyk, M., Schmaus, M. et al. Reducing or Widening the Gap? How the Educational Aspirations and Expectations of Turkish and Majority Families Develop During Lower Secondary Education in Germany. Köln Z Soziol 74, 259–285 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-022-00844-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-022-00844-5