Abstract

International social alliances—in which multinational enterprises (MNEs) and social enterprises (SEs) collaborate—are a vital source for the development and scaling up social innovations for value creation. Yet, these alliances face significant legitimacy challenges, which are more glaring in bottom-of-the-pyramid markets (BOPMs) within emerging and developing economies owing to weak and underdeveloped formal institutions. Drawing on the legitimacy, institutional, and social alliances literature, we develop a conceptual framework that explains the importance of developing social, institutional, and commercial legitimacy in international social alliances operating in BOPMs. We also explored the challenges faced by international social alliances in BOPMs and the factors that enable MNEs and SEs to build different types of legitimacy. We contribute to international business research by providing an understanding of various legitimacy building strategies enacted by international social alliances based in BOPMs for social value creation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There has been an increasing scholarly interest in examining social innovation and how it is enacted across different contexts (Adomako & Tran, 2022; Arranz et al., 2020; Dionisio & de Vargas, 2020; Rao-Nicholson et al., 2017; Unterfrauner et al., 2019). In contrast to technology-focused innovation, social innovation places greater emphasis on social, rather than just economic, objectives. Social innovation can be defined as the “development and implementation of new products, services or models to meet social needs and create new social relationships” (Murray et al., 2010: 3). Social innovation offers novel solutions to social problems, whereby the value generated benefits whole society, rather than individuals (Phills et al., 2008). Social innovation can have a wide range of outcomes that offer superior living conditions through improved health, social well-being, education, and employment, thus paving the way for better social inclusion, social justice, and social welfare. The growing impetus around social innovation is evident in the initiatives of the European Commission (EU Horizon 2020), the European Union’s Social Innovation Initiative, and the USA’s Social Innovation Fund. Such initiatives highlight the vital role played by social innovation in addressing pressing grand societal challenges.

Social enterprises (SEs) have made considerable contributions in fuelling social innovation globally. SEs are hybrid entities that address social needs through commercial activities (Esposito et al., 2022). They are hybrid because they simultaneously handle the contradicting logic of meeting commercial and social goals (Gigliotti & Runfola, 2022; Mason & Doherty, 2016; Zahra & Wright, 2016). Examples of SEs operating across the globe include Yunus Social Business, Arus Education, Micro X Labs, and Fab Foundation. SEs are sought by businesses, and public and governmental organizations to conduct research and find solutions for many pressing social issues, as they are locally embedded in such contexts and are aware of the prevailing opportunities and challenges (Ramani et al., 2017). SEs also seek collaborative partnerships with public and private organizations that can provide them with the resources and capabilities that are required to tackle complex social issues. Indeed, research on SEs has considered the importance of social networks across business disciplines (Bauwens et al., 2020; Gillett et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2021; Sakarya et al., 2012). In recent years, the social network perspective has gained prominence in the international business domain (Cuypers et al., 2020; Gözübüyük et al., 2020).

In such a context, attention is being devoted to the relevance of social alliances between SEs and multinational enterprises (MNEs) (e.g., Danone-Grameen Bank, Shell-d.light). As Gold et al. (2020) argued, social alliances between SEs and businesses are crucial in creating value by combining the social and traditional business logic in bottom-of-the-pyramid markets (BOPMs). Such alliances offer social capital and key know-how which are vital for the wider development of SEs, and are also beneficial in fostering social capital development in resource constraints communities for the generation of social impact (Littlewood & Khan, 2018). Social alliances play an important role in addressing grand social challenges through social innovation, while also enabling the capability development of alliance partners (cf. Kolk & Lenfant, 2015; Van Tulder et al., 2016).

SEs are especially relevant to BOPMs, which are very common in emerging and developing economies (Brix-Asala et al., 2021; Gold et al., 2020; Webb et al., 2010). BOP markets comprise around four billion people (70% of the world’s population) who mainly live in developing or emerging markets and constitute a five trillion-dollar per-year bloc of potential consumers that survive on less than two dollars per day (Hart & Christensen, 2002; Muthuri et al., 2020; Webb et al., 2010). These markets are often underserved (i.e., they face exclusion) and hence offer challenging but immense market potential for MNEs to engage in social innovation via the development of new products or services aimed at addressing societal needs. They pose ample avenues for MNEs, especially from an international business perspective, to expand their market and product scope for the generation of mutual value. These markets also suffer due to prevalent institutional voids (that may hinder market development, market participation, and market functioning), and SEs can play an important role in addressing such voids (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; Rao-Nicholson et al., 2017). This also calls for international venturing strategies (i.e., the adoption of frugal innovation) that consider the socio-economic and cultural contexts found in BOPMs, which, in turn, can establish an emotional connection with consumers.

In this study, we specifically focused on international social alliances in BOPMs, which could enable social innovation in the context of emerging and developing economies. Prior research indicates that alliances between MNEs and SEs could lay the foundations for a successful BOP business model (Andersen & Esbjerg, 2020). The extant literature has largely examined the joint development of capabilities, collaboration strategies, dynamics of power, and conflicts in social alliances (Berger et al., 2004; Huybrechts et al., 2017; Sakarya et al., 2012). Such partnerships are also formed to seek legitimacy, which is vital for a firm’s survival, aid access to resources, gain acceptability from relevant stakeholders, and overcome the liability of newness that is often associated with social innovation (Dacin et al., 2007; Dart, 2004; Sandeep & Ravishankar, 2015). When operating in emerging and developing markets that have underdeveloped and weak institutions, firms are particularly prone to issues linked to a lack of legitimacy (Khan et al., 2015; Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). According to Suchman (1995: 574), legitimacy is “a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions”. From an international business perspective, legitimacy can play a significant role in garnering trust and acceptability for a new product or service and overcoming any imperfections or constraints found in BOPMs, which, in turn, influence product or service attributes, and a firm’s distribution, pricing, and promotional campaigns. Yet, relatively few studies have explored international social alliances from a legitimacy perspective in the international business domain (Marano & Tashman, 2012; Kibler et al., 2018). As Sinkovics et al. (2014) argued, MNEs need to develop a capability of social embeddedness to generate business models that create social value in BOPMs.

Legitimacy can potentially offer dual (social and commercial) benefits to international social alliances involving SEs and MNEs. The establishment of partnerships with SEs can provide MNEs with the social legitimacy they need to operate in BOPMs (Webb et al., 2010), and may enable them to overcome institutional voids in such host markets, leading to their higher chances of survival. Moreover, association with MNEs can provide SEs with commercial legitimacy, as they often lack experience in handling commercial engagements, especially in terms of achieving economies of scale, and scaling up social innovation (Barraket et al., 2016; De Silva et al., 2020; Mitchell et al., 2015), and marketing their products or services for both bottom- and top-of-the-pyramid markets for the creation of social and economic value (cf. De Silva et al., 2020). In recent years, leading MNEs have formed international social alliances to deliver social value, which in turn enabled them to establish legitimacy. For example, Coca-Cola has formed partnerships with various SEs in different parts of the world to address social and environmental challenges, particularly those related to water conservation and community development (The Coca-Cola Company, 2023). This partnership exemplifies the proposition related to social legitimacy (Schätzlein et al., 2023). Coca-Cola collaborates with SEs to leverage their extensive networks and social reputation, thus gaining social legitimacy in various communities.

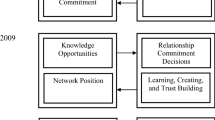

Drawing insights from the international business literature and institutional theory, we developed a conceptual model to explore MNEs and SEs cooperation in building legitimacy through social alliances, which is driven by (i) market constraints concerning the institutional environment of BOPMs, (ii) attributes of social innovation from BOPMs’ consumers’ perspective, and (iii) characteristics of SEs and international social alliances.

The paper makes several contributions. First, this study contributes to the international business literature by offering conceptual insights into the legitimacy requirements of both MNEs and SEs in forging international social alliances, specifically in BOPMs. Our findings throw light on the effects of market constraints (institutional environments) and the attributes of social innovation (sophistication and scalability) that necessitate the formation of international social alliances between MNEs, SEs, and other stakeholders to build legitimacy. This is significant considering the lack of international business studies on international social alliances from a legitimacy perspective (cf. Cuypers et al., 2020; Dart, 2004; Littlewood & Khan, 2018). Second, we addressed the influences of BOPMs’ consumer mindsets, which are based on aspects like affordability and resistance to change and may dictate the legitimacy needs of social innovation ventures formed between SEs and MNEs. Third, we developed a model suited to depict the need for social innovation and reputation of SEs in local environments to enable the formation of international social alliances with MNEs, which, in turn, support the development of social, institutional, and commercial legitimacy. We also developed several propositions that pave the way for future research studies on this important topic. Finally, we elucidate the characteristics that make SEs attractive partners for MNEs (to make up for their lack of legitimacy) in BOPMs while also exploring the forms of legitimacy that SEs lack, which are complemented by MNEs in local social alliances. Thus, our findings provide a more fine-grained understanding of the legitimacy contributions of both MNEs and SEs, which can complement one another in international social alliances, thus developing social innovation for BOPMs.

2 Conceptual Background

2.1 Social Enterprises and Legitimacy Building in Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Markets

Social enterprises (SEs) are hybrid organisations that aim to address social issues by engaging in commercial activity (Dacin et al., 2010; De Silva et al., 2020). This implies that such organizations seek a double-bottom line by focusing on both social and economic goals and are thus neither typical charities and non-profits nor commercial business enterprises. Three conditions have been suggested for firms to qualify as SEs (Ramani et al., 2017): (i) having market or non-market offerings that address social needs; (ii) being financially viable; and (iii) applying business management principles. As such, SEs are required to handle the competing logic involved in the simultaneous pursuit of social and commercial goals to attain mutual value creation for their local communities (cf. De Silva et al., 2020). They need the revenue generated from commercial activities to sustain their efforts towards the achievement of social objectives (Mason & Doherty, 2016). Some SEs may be more profit-oriented than others, depending on where they sit within the hybrid spectrum, but they need to have a social mission (Agarwal et al., 2018). The extent to which they give preference to social goals over commercial ones may depend on their origins and initial formation (Zahra et al., 2008). Due to competing social and commercial needs, their dual mission can cause SEs to face legitimacy issues in the eyes of relevant stakeholders (Mason & Doherty, 2016), which can cause them to struggle to acquire credibility (Sandeep & Ravishankar, 2015).

For SEs, a strong focus on both economic and social goals can create institutional ambiguity (Townsend & Hart, 2008). Commercial logic is more focused on economic surplus and higher returns, with an emphasis on competent technical and managerial expertise and a reliance on hierarchical structures as preferred governance mechanisms. The social logic is more focused on generating social value, relying mainly on governance mechanisms that are more democratic and may depend more on volunteers than paid staff (Pache & Santos, 2013). When dealing with this pluralism, SEs may encounter situations in which they need to make trade-offs and prioritise commercial and non-commercial social logics (Yang & Wu, 2016). For example, microfinance SEs are sometimes caught between the banking logic (i.e., setting high-interest rates to maximise profits) and the development logic (reducing interest rates for poor and underserved customers). Some of them have been shown to compromise by setting interest rates at intermediate levels (Pache & Santos, 2013). This duality also causes internal tensions for SEs in terms of priorities, values, and identities, which could hamper the development of social innovation. Another reason for the dual focus is the fact that SEs and other traditional charitable organisations cannot rely entirely on government funding and other such sources continually (Mitchell et al., 2015). For example, the UK’s government policies encourage SEs to be financially independent, while Social Firms UK recognises only those SEs that can generate at least 50% of their revenues via commercial activities (Mason, 2012).

Social enterprises also require legitimacy to overcome their ‘liability of newness’ (Suchman, 1995), especially while pursuing social innovation (Ruebottom, 2013). Legitimacy is required to propagate any ideas and thoughts related to the new social realities and market products/services brought about by social innovation (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). SEs also need to be perceived as credible institutions by relevant stakeholders (financiers, communities, government, and regulatory bodies) concerning their ability to drive, manage, and scale up commercially viable operations (Mason, 2012). SEs embedded in local communities, seek to address the social issues facing their host communities by developing novel solutions, which leads to significant institutional pressure (Pache & Santos, 2010; Seelos et al., 2011). As per institutional theory, the need for legitimacy pressures organisational entities to conform to institutional frameworks, which include regulative, normative, and cognitive elements (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 1995). MNEs can achieve this conformity through processes of coercive, normative, and mimetic isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Laws, regulations, and rules contribute to regulative or formal institutional arrangements, while informal institutions (normative and cognitive) draw from the cultural, moral, ethical, and social domains (Peng et al., 2009). Thus, institutions dictate the behaviour and strategic choices of organisations, making any deviations from acceptable institutional practices potentially costly for firms in terms of higher transaction costs (Lawrence et al., 2001; Peng, 2003). From an international business point of view, the additional risks that emerge from a lack of legitimacy may prevent firms from gaining acceptance from consumer groups and regulatory and government bodies, which, in turn, can restrict access to markets (Phillips et al., 2000). Thus, organisations are sometimes viewed as legitimacy-seeking systems (Dart, 2004).

The extant literature has addressed several forms of legitimacy—i.e. pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy (Suchman, 1995); social, relational, investment, alliance, and market legitimacy (Dacin et al., 2007); and formal and informal legitimacy (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). However, as they operate within a competing duality of logics, SEs struggle to simultaneously pursue both commercial and social legitimacy in the eyes of multiple stakeholders (Newth & Woods, 2014); hence, our conceptual model addresses these two forms of legitimacy. Social legitimacy denotes the level of social appropriateness, acceptance, and desirability of a firm’s existence and behaviour, and the contributions it makes to the general social good (Agarwal et al., 2018; Marano & Tashman, 2012). Conversely, commercial legitimacy refers to the perceived credibility of a firm in engaging in financially viable commercial trade, which stems from a history of sound financial performance and efficient business management in operating markets, and good infrastructure with a professional and competent workforce (Pache & Santos, 2013; Yang & Wu, 2016). In this study, we examine international social alliances operating in BOPMs—in which the legitimacy requirements of informal institutions are more prevalent because of the weakness of formal ones (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015; Dau et al., 2022)—we also focused on informal institutional legitimacy, which denotes the degree to which firms adhere to informal institutions, including the idiosyncratic norms, culture, tradition, ethics, and beliefs prevalent in the operating markets (cf. Dau et al., 2022; Peng et al., 2009; Rivera-Santos et al., 2012).

2.2 Social Innovation and International Social Alliances in Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Markets

Typically, international social alliances involve at least one partner with a focus on social goals and social value creation (which may be a non-profit or a SE) with the other partners being MNEs; hence, the alliance’s objectives can have both financial and social goals for mutual value creation (Berger et al., 2004). Prior research indicates that alliances between MNEs and SEs can lay the foundations for successful BOP business models and are a vital source of social innovation (Andersen & Esbjerg, 2020; Huybrechts et al., 2017). International social alliances differ from their commercial business counterparts as their key objectives could be finding solutions for societal challenges. These alliances are primarily based on resource complementarity and the co-creation of capabilities to achieve both commercial and social value (Selsky & Parker, 2005; Siemieniako et al., 2021). SEs operating in BOPMs contribute in terms of local knowledge and social capital through their social ties, networks, and trust with local communities, while MNEs contribute financial, technical, and managerial resources (Meng et al., 2023; Sakarya et al., 2012). The alliance-level objectives of such ventures include the creation of joint value and the building of community capacity (Sakarya et al., 2012). This helps to enhance the reputation and stakeholder appreciation of MNEs while helping to fund and enhance the image of SEs as well as enabling them to gain valuable knowledge for both social and economic value creation.

Some studies argue that international social alliances foster dependency on foreign aid and philanthropy, which may hinder the development of self-sustaining solutions and local capacity building by SEs and ultimately fail to effectively address the root causes of social challenges (Ceesay et al., 2022). Instead of enhancing the ability of SEs to address social challenges independently, social alliances may become accustomed to relying on ready-made solutions from external entities, including MNEs (Cacciolatti et al., 2020). This can further limit the autonomy and self-determination of SEs, which can undermine the legitimacy, ownership, and relevance of any initiatives aimed at addressing local challenges (Weidner et al., 2019). Despite these concerns, the proponents of international social alliances argue for a more balanced approach, wherein local SEs should take the lead in identifying problems, designing solutions, and driving initiatives while working with MNEs (Liu et al., 2021). A shift from short-term projects to long-term partnerships between MNEs and SEs could address the root causes and systemic issues of social challenges. This approach recognizes that sustainable change requires persistent efforts over time.

Collaboration between an MNE and SE can benefit both partners because it can enable them to separately focus on social (for SEs) and economic (for MNEs) objectives, which is what they do best (Yang & Wu, 2016). Approaches based on collaboration (rather than on competition) also better equip SEs to address the conflicts caused by pluralism in gaining dual legitimacy (i.e., social and commercial) from multiple stakeholders (Sandeep & Ravishankar, 2015). Such collaborative efforts can lead to social innovation that manifests itself in new or modified products, processes, technologies, or services that are suitable for BOP markets. In turn, social innovation can yield much-needed social value (Sinkovics et al., 2014), which may benefit underprivileged and underserved BOPM communities. As shown in Table 1, previous studies considered the interlinkages between social alliances and social innovation. Indeed, the extant scholarship suggests that social innovation is embedded in the social linkages with external partners that help MNEs extend their CSR efforts by setting new goals.

Social innovation can yield positive outcomes that contribute to satisfying the basic needs of a society, which can pertain to better health, education, employment, environmental protection, and poverty alleviation, etc. The potential of such innovation to generate a social impact is one of the main reasons why it is being extensively promoted by governments and other institutions (e.g., the EU’s Social Innovation Initiative, the USA’s Social Innovation Fund, the United Nations, and the European Commission). To be successful, any innovation needs to prove its feasibility in financial terms (viability) and in generating social impact (scalability) (Newth & Woods, 2014). Social innovation also requires resources in the form of infrastructure, finance, and human and collaborative networks (cf. Littlewood & Khan, 2018; Singh et al., 2023). Innovation can take the form of new or modified products, processes, services, technologies, interventions, business models, or combinations thereof (Choi & Majumdar, 2015). Social innovation comes in four broad categories: (i) focused on institutional change; (ii) improving quality or quantity of life; (iii) for the public good; and (iv) addressing social issues not met by business markets (Pol & Ville, 2009). Our study focuses on social innovation in BOPMs—i.e., addressing any unmet issues in these underserved markets by creating new products or services that deliver social value.

Despite its importance, social innovation is associated with the liability of newness that can hinder or challenge the potential of new initiatives in gaining legitimacy and trust within their respective ecosystems (Battistella et al., 2021; Nicholls et al., 2015). One of the primary challenges faced by social innovation is that it often challenges existing norms, systems, and power structures. This may lead to scepticism and resistance from any individuals, organizations, or communities that are keen in maintaining the status quo. Particularly, as social innovation due to its newness lacks a track record or an established reputation, it can struggle to gain the trust of potential stakeholders, including investors, partners, and beneficiaries (Reiser & Dean, 2017). The absence of a proven history of impact can hinder access to resources and support and thus the ability of social innovation to gain momentum (Pel et al., 2020). Moreover, the motivation and creativity of individuals drive the impetus to solve social needs. As argued by Battistella et al. (2021), the expected impact of social innovation should be aligned with the mission of SEs. In this regard, the different views, expectations and values of stakeholders should be considered. As such, the development of social innovation by SEs faces challenges in defining its motivations and vision (Alberio & Moralli, 2021).

Against this background, international social alliances between MNEs and SEs can be instrumental in addressing the challenges associated with the liability of newness in social innovation. Engagement with internal and external stakeholders is vital for generating social innovation because their acceptance and cooperation are crucial to ensure success at different stages (cf. Herrera, 2015; Littlewood & Khan, 2018). Social innovation can face several challenges, especially in BOPMs. Consumers may reject innovation and fail to understand its potential benefits (Gold et al., 2021; Ramani et al., 2017), which can represent a significant challenge for any marketing function as it might require the adoption of a marketing mix. Under these circumstances, it is critical that social innovation suit each BOPM’s socio-cultural settings to attain much-needed legitimacy and ensure its scaling up and further adoption by consumers. To get past the risk of being too new (Dacin et al., 2011), social innovation needs to gain legitimacy. This means becoming accepted by society and fitting in with the informal institutional frameworks that are common in emerging and developing markets. The perceived newness, market scepticism, and sophistication associated with social innovation can potentially contribute to this liability of newness (Dart, 2004; Decker & Obeng Dankwah, 2023).

Driving social innovation also requires institutional support, which is often absent in BOPMs, especially from formal institutions (Zahra et al., 2009). Hence, the market imperfections that are prevalent in BOPMs—in terms of lack of appropriate market access, market power, market security, and market homogeneity (Webb et al., 2010)—make it imperative for firms to resort to informal institutions to attain the legitimacy they need to design and develop social innovation. Further, the acceptance of any product or service delivered by social innovation by the BOPMs’ consumers—who are mostly low-income and cannot afford to get it wrong—is mainly determined by its affordability, price performance, and social value proposition (Anderson & Markides, 2007; Christensen et al., 2006; Newth & Woods, 2014).

Many MNEs engage in social innovation as an extension of their CSR commitments; this is normally referred to as corporate social innovation (cf. Adomako & Tran, 2022; Dionisio & de Vargas, 2020). However, MNEs are often perceived as sources of environmental and societal issues and are therefore not trusted enough by consumers and other relevant stakeholders in society (Zhao et al., 2014). Hence, they are likely to suffer from a lack of social legitimacy (or acceptance), especially when serving BOP consumers through social innovation. BOP markets are more strongly reliant on informal institutions due to their lack of efficient and effective formal ones (London & Hart, 2004; Webb et al., 2010). Institutional support also proves to be very crucial for social innovation (Mair & Marti, 2009; Zahra et al., 2009). In the absence of formal institutions, MNEs have to rely on informal networks, which they can struggle to access because they have little knowledge of local markets and their prevailing customs, traditions, and beliefs (Scott, 2008). Hence, MNEs are also likely to suffer from a lack of informal legitimacy, which is vital to drive social innovation in BOPMs. These different institutional logics significantly hinder MNEs from establishing legitimacy in BOP markets, thus making international social alliances highly relevant to such contexts.

Social enterprises, on the other hand, are likely to be more locally embedded, while also enjoying the trust and support of local communities (Tracey & Phillips, 2011). This social acceptance (social legitimacy) is very closely linked to the social causes that SEs pursue as well as the social value these enterprises generate for local communities. The networks, trust, and reciprocity (social capital) that SEs establish also serve as mechanisms suited to potentially replace formal institutions in BOPMs (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015). Thus, through their local embeddedness, SEs are better equipped to acquire the informal legitimacy that is essential to overcome the liability of newness (resistance to change) that comes with most social innovation (Dacin et al., 2011; Ruebottom, 2013). Hence, MNEs can potentially address their lack of informal and social legitimacy by forming international social alliances with SEs that have good social reputations, local presence, knowledge of the market, and community support. SEs, on the other hand, are generally perceived to be commercially inferior (Mitchell et al., 2015; Pache & Santos, 2013), especially in scaling up social innovation and achieving the economies of scale needed to be financially sustainable. This is mainly attributed to a lack of resources, infrastructure, and business acumen. Thus, SEs can tackle their lack of commercial legitimacy by forging international social alliances with MNEs, which have the resources and capabilities required to drive social innovation in BOPMs.

Drawing from the literature on the legitimacy of SEs, we focused on the characteristics that make SEs appear more socially acceptable but commercially inferior and, in turn, require them to enter into social alliances with MNEs to enhance the legitimacy of their joint ventures for social value creation in BOPMs (Ramadan et al., 2023). Considering the significance of institutional frameworks in attaining legitimacy and driving social innovation in BOPMs, we highlight how the effects of market imperfections or constraints can motivate MNEs to collaborate with SEs to enhance their informal legitimacy. In addition, we discuss how the attributes of social innovation can generate the liability of newness and encourage MNEs and SEs to form international social alliances, thereby enhancing the legitimacy of their ventures. Finally, from the BOPMs’ consumers’ perspective, the legitimacy needs of a venture can potentially influence the attributes of any product or service delivered by social innovation.

3 Conceptual Framework and Research Propositions

This section presents the conceptual framework (as shown in Fig. 1) and develops the relevant propositions. By drawing insights from the legitimacy literature, Fig. 1 shows how the characteristics of SEs in local communities and their focus on social innovation can lead MNEs to engage in international social alliances with SEs to gain social, institutional, and commercial legitimacy.

3.1 Social Legitimacy

Multinational enterprises are often perceived to be in the business of maximising profits and, as such, to not be trusted by relevant stakeholders as being interested in addressing pressing social causes or benefiting society (Zhao et al., 2014). They are often seen to be engaging in such endeavours as publicity gimmicks aimed at enhancing their social image as socially responsible businesses. A case in point is represented by Fast Fashion global brands, which are often accused of greenwashing (The Financial Times, 2023). MNEs often come under the scrutiny of governments, activist groups, and public interest concerns for being socially irresponsible (e.g., Gap, Nike, H&M, and BP, to name a few). Coca-Cola, for example, lost the license that allowed it to extract water for its plants in India due to allegations of groundwater depletion (Bijoy, 2006). Under such circumstances, MNEs need social licenses to operate in resource-constrained markets, which, in turn, requires them to engage with multiple stakeholders (cf. Ho et al., 2022; Moffat & Zhang, 2014).

Large corporations or firms are often not trusted by BOP consumers, who are largely illiterate and poor, and they fear being taken advantage of (Bertrand et al., 2006; Gold et al., 2020). Hence, in trying to create or develop new products or services for BOP markets, MNEs are likely to face resistance from local communities, especially if they have no prior experience in such markets, and are thus likely to receive less social acceptance and support. In BOP markets, traditional partners are often inconstant or absent (London & Hart, 2004), and the SEs operating in such markets thus prove to be more suitable alliance partners for MNEs to overcome this lack of acceptance and its associated mistrust. Several leading MNEs are forming partnerships with SEs to gain social licenses and acceptance when operating in different markets. For example, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has established a longstanding partnership with Save the Children to improve child health and nutrition in vulnerable communities worldwide (GSK, 2023). This collaboration, which focuses on healthcare access and education, enables GSK to enhance its social legitimacy and trustworthiness in the context of improving child health and nutrition.

Due to the nature of their pro-social business models, SEs may not be as opportunistic as traditional partners, have access to wide-reaching networks, and are socially embedded in local communities (Webb et al., 2010). SEs enjoy the trust of such communities as they are perceived to be oriented towards social justice, equality, and social welfare (Sakarya et al., 2012). They are also likely to become opinion leaders as they promote specific social causes and work towards addressing the social issues facing their local communities. Some SEs can be thought of as leaders in a specific area (Berger et al., 2004); for instance, by pioneering new programmes and practices aimed at improving the health of children and women. When such SEs endorse some food products as healthy, consumers will then value and trust those products more, and those who are invested in this cause may buy them. Prior engagements that have benefited society contribute further to these SEs credibility and enhance their ‘social’ brand equity (Sakarya et al., 2012). Just as commercial firms emphasise brand equity to gain reputation, visibility, and customer loyalty, SEs also enjoy social brand equity by way of their involvement and engagement in programmes that cater to the betterment of society. SEs endowed with greater social brand equity enjoy the respect and trust of their local communities and other regulatory bodies—and, more importantly, the average BOP consumer. Hence, by associating with SEs, MNEs are more likely to gain the social legitimacy they need to operate in BOPMs. Hence, we proposed:

P1a. The more an SE (i) has established extensive networks in local communities, (ii) is an opinion leader in the eyes of the relevant stakeholders, and (iii) has gained a reputation through social value creation with prior engagements, the more likely it is an MNE will engage in an international social alliance with it to secure social legitimacy for the venture

In BOPMs, social innovation requires a thorough understanding of the local context in terms of its socio-cultural elements. MNEs often lack this, hence the need to collaborate with local entities. There are examples like Credit Suisse’s partnerships with microfinance institutions, whereby these MNEs gained social legitimacy through collaborations in social innovation ventures. In turn, this helped them expand their presence in emerging markets (Mirvis et al., 2012, 2016). Most social innovation comes with social change, and overcoming the related liability of newness (Dacin et al., 2007; Dart, 2004) is one of the focus areas for many SEs engaged with such initiatives. The nature of the social innovation determines the extent of the social change required, which can vary from small incremental adjustments to large systemic ones that transform existing social systems (Zahra et al., 2009). Hence, the perceived newness of a change to a local context may trigger greater resistance because it may not conform to existing institutional (socio-cultural) norms and hence necessitate the establishment of social legitimacy (Ruebottom, 2013) through collaborations with SEs. BOPMs’ consumers are also bound to display market scepticism (Mangleburg & Bristol, 1998), which is a lack of trust in motives that consumers harbour when they suspect that any claims made about a product or service may be misleading. For BOPMs’ consumers, this distrust can be more accentuated towards MNEs, who are mostly viewed as mere profit-seeking entities (Bertrand et al., 2006). Hence, consumers are very much guarded against any initiatives that may result in them being taken advantage of; such situations demand greater social acceptance or legitimacy, which is achievable via international social alliances.

Consumers based in BOPMs may reject innovation because they cannot fully understand its potential benefits or use it due to a lack of the required skills or assets (Ramani et al., 2017). This is often the case if an innovation is very sophisticated, and BOPM consumers struggle to adapt it to their needs. SEs thus often resort to various activities—like educating consumers and spreading awareness—to facilitate the adoption of social innovation through their social alliances with MNEs and goodwill. For example, co-creation and distribution are examples of avenues of cooperation between MNEs and SEs. When Godrej and Boyce decided to develop a watered-down, cheap version of a refrigerator for the Indian rural market, they involved village women in the design process to ensure its acceptability. Further, the product was distributed by members of a micro-finance group (New Atlas). Hence, MNEs are more likely to resort to alliances with SEs to build the social legitimacy required to secure the social acceptance of innovation by BOPM consumers. This led us to suggest that:

P1b. The greater the levels of perceived (i) newness, (ii) market scepticism, and (iii) sophistication of social innovation in a local context, the greater the likelihood of MNEs forming international social alliances with SEs to acquire social legitimacy for the venture

The average BOPMs’ consumer may be uneducated and not have a regular source of income and, hence, may exhibit interests, behaviours, and priorities that are very different from those of urban or semi-urban consumers (Chelekis & Mudambi, 2010). Another characteristic of BOPMs’ consumers is that they often exhibit high brand loyalty (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015)because, being poor, they cannot afford to take the risk of switching brands. Hence, the pricing of any products/services introduced to BOPMs (as part of social innovation ventures) is vital for social acceptance and to convince consumers to buy such products/services and possibly switch from any existing ones. Thus, affordability is a very important aspect that has the potential to drive and dictate the course of social innovation, especially if enhancing social legitimacy is crucial for the venture. The more affordable an innovation is, the better it justifies the social value of the related products/services. The purpose served by innovation is equally important in terms of its performance—i.e., it must either meet a hitherto unmet need or satisfy it better. Thus, a product/service’s price/performance ratio also needs to be attractive for it to be socially accepted (Christensen et al., 2006). In addition, the products/services in BOPMs also need to have value propositions that highlight their social aspects (Ramani et al., 2017). This is needed for the social acceptance of any product/service because it resonates with the ideas of social justice, equality, and integration. Thus, we suggested:

P1c. The greater the international social alliance venture’s need for social legitimacy, the more likely it will be to have a greater focus on (i) affordability, (ii) an attractive price-performance ratio, and (iii) social value propositions

3.2 Institutional Legitimacy

BOPMs are characterised by several market-related constraints (London et al., 2010), such as lack of market access (lack of market information, standards, and requirements; poor infrastructure); lack of market power (lack of proper links to buyers, suppliers, and other markets; information asymmetry; lack of transparency and enforcement); and lack of market security (fluctuation in demand and price; lack of alternative markets). BOPMs are also heterogeneous (Dembek & York, 2022; Hammond et al., 2007) and will present institutional elements that vary between rural pockets or regions. Further, BOPMs also exist in urban areas—for example, in slums located right in the middle of major cities like Mumbai (India)—and may be very different from rural BOPMs (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015). This implies that firms operating in BOPMs, especially from an international business perspective, are dealing with multiple heterogeneous BOPM segments (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015). This also means that any legitimacy requirements will also need to cater to the heterogeneity of BOPMs for mutual value creation.

The institutional environments in BOPMs located in emerging and developing economies are very unstable and underdeveloped (Khanna & Palepu, 1997). BOPMs are almost devoid of or have unstable and non-functional formal institutions; hence, their socio-economic activities are mostly driven by informal institutions (London & Hart, 2004; Webb et al., 2010). Personal networks based on mutual trust, understanding, obligation, and reciprocity—along with taken-for-granted business practices—often play a major role in such environments, which makes it even more difficult for outsiders to operate in them (Tracey & Phillips, 2011). Informal institutions are likely to drive the institutional legitimacy needs in such markets (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015). However, the SEs that operate in such markets are often adept at dealing with these conditions and use their social capital via personal relationships, mutual trust, and reciprocity to negotiate the institutional voids (Webb et al., 2010). MNEs, on the other hand, are more likely to struggle with the informal mechanisms prevailing in such markets; this, in turn, poses significant challenges for them to gain the social license they need to operate in them. Hence, the greater the uncertainties in BOPMs concerning these constraints, the more likely MNEs will resort to alliances with SEs to enhance their informal institutional legitimacy. Based on this discussion, we proposed the following:

P2a. The greater the lack of (i) market access, (ii) market power, (iii) market security, and (iv) market homogeneity, the more likely MNEs will be to engage in international social alliances with SEs to acquire informal institutional legitimacy for their ventures

As mentioned earlier, social innovation mostly involves social change and may require behavioural changes in consumers’ attitude (El-Baba & Fakih, 2023). Further, in BOPMs, social innovation is highly likely to challenge existing societal norms, culture, traditions, and prevailing beliefs—by challenging existing moral and cognitive frameworks—and to play an important role in dictating what social behaviours are acceptable in BOPMs. In such situations, SEs often resort to rhetoric and narratives to build institutional legitimacy (informal) and to gain acceptance for new ideas driven by social innovation (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994; Creed et al., 2002). Rhetoric and language can be effectively used by SEs to propagate ideas related to new social realities validate arguments, and thus build the credibility required to drive social innovation (Dacin et al., 2011; Watson, 1995). Rhetoric or narratives can either appeal to the cultural mindset and beliefs found in BOPMs, effectively challenging them by aligning the change agenda to the potential benefits or interests of the community. These strategies help SEs overcome the liability of newness associated with social innovation.

An example of this can be represented by the social change associated with the sanitary pad revolution in India (BBC, 2014). This social change went against the existing myths, traditions, and prevailing beliefs of rural women in India, which were just some of the obstacles to the adoption of low-cost sanitary pads. In such cases, the scepticism of BOPMs’ consumers and the fear of going against norms and traditions can potentially reduce the credibility of such ventures. Hence, there is a need to build sufficient informal legitimacy by establishing new social realities that need to be institutionalised. Thus, the more social innovation is new and sophisticated to BOPMs, the more likely it is to challenge current informal institutional settings, which makes it even more necessary for MNEs to engage with SEs to enhance their informal institutional legitimacy, which can also support their moral and cognitive legitimacy (cf. Barron, 1998; Foreman & Whetten, 2002). Therefore, we proposed:

P2b. The greater the levels of perceived (i) newness, (ii) market scepticism, and (iii) sophistication of social innovation in a local context, the greater the likelihood of MNEs forging international social alliances with SEs to enhance their informal institutional legitimacy for their ventures

3.3 Commercial Legitimacy

Social enterprises are required to be both socially and commercially legitimate (Newth & Woods, 2014); as such, they have a double bottom line—i.e., they focus on both commercial and social goals (De Silva et al., 2020). However, the pressures for SEs to be financially viable are increasing, and they are finding it difficult to sustain their operations by relying only on government or public funding and donations (Mason, 2012; Mitchell et al., 2015). Furthermore, these factors will determine the level of their commercial engagement and the importance of being seen as commercially legitimate. Engaging in different social causes can require varying levels of resources. Addressing pressing social issues will require greater resources—i.e., financial, managerial, technical, and infrastructural ones (Mair & Marti, 2009). If SEs lack these resources or capabilities, the relevant stakeholders may not perceive their ventures as commercially legitimate. Further, SEs need to reinvest the revenue generated from commercial activities in their other social missions and sustain their efforts towards social value creation (Arslan et al., 2022; Mason & Doherty, 2016). SEs may also lack the experience needed to operate commercial ventures.

Increasing numbers of SEs are now operating in highly competitive environments in which they have to compete for funds and resources with other non-profit organizations, charities, third sector organizations, as well as commercial businesses (Sakarya et al., 2012). This means that they need to be able to develop competitive advantages, be more efficient, and prove their ability to trade to survive in such markets (Mason, 2012). SEs can also have strong competitors in BOPMs, especially in urban ones. Prior research indicates the presence of competition between MNEs and domestic companies in BOPMs (Angeli & Jaiswal, 2015). To address some of these issues and strive to be perceived as more commercially legitimate, some SEs try to adopt more professional management practices and structures, while trying to imitate other commercial entrepreneurial ventures or successful SEs. For example, SEs are seen to adopt formal business planning and structure to achieve legitimacy while seeking investment and engagement from financial stakeholders (Barraket et al., 2016). An example is Microsoft Canada which has joined forces with NGOs and SEs, like the CIBC Foundation, to help increase access to skills-based training, certifications and employment while advancing the digital economy. The social impact alliance of Microsoft and the CIBS foundation is helping NPower Canada to bolster current job training programmes and expand the Canadian Tech Talent Accelerator programme (Microsoft, 2022). Microsoft is thus compensating for institutional voids and gaining commercial legitimacy while expanding its presence in emerging markets.

In some cases, SEs have indicated that they are not perceived to be professionally and financially strong, especially if they have a non-profit status, which can sometimes prove to be a hurdle when they want to compete in markets with a certain business image (Pache & Santos, 2013). Another example would be Aspire, which is a UK-based social venture that was initially very successful in helping the homeless. However, when it decided to expand and grow (in a franchising mode) to achieve the economies of scale needed to be commercially viable, it failed because of several issues with its business model (Tracey & Jarvis, 2007). Another SE that competes with commercial firms has reported that an excessive emphasis on its social mission had adversely affected its ability to procure more customers (Mitchell et al., 2015). This prompted it to adopt an external commercial outlook while satisfying its social obligations internally. Some SEs even downplay their social mission in their promotional materials for revenue generation, instead emphasising product quality (Mitchell et al., 2015). Many SEs also recognise the negative impact of commercial failure on their social missions, which may pose questions about their credibility and commercial legitimacy. All of the above discussions indicate a general notion of SEs as commercially inferior, which can contribute to a lack of commercial legitimacy in their pursuit of commercial activities. This led to the following proposition:

P3a. The more an SE (i) is subject to competition from other commercial ventures, (ii) is subject to pressures to be financially viable, (iii) has resource-intensive social causes to address, and (iv) is relatively less experienced in handling commercial activities, the more likely it will be to engage in international social alliances with MNEs to acquire commercial legitimacy for the venture

Designing social innovation in terms of products or services often requires SEs to think like mainstream commercial businesses managing consumer expectations, market characteristics and suitability to the local context (Ramani et al., 2017). One of the important success factors for social innovation is the extent of its social impact, which places greater focus on its scalability, which also involves several challenges. The business dimension plays a vital role in the scalability and sustainability of social innovation (Sandeep & Ravishankar, 2015). As discussed earlier, SEs are often perceived as lacking business acumen in such situations (Tracey & Jarvis, 2007). SEs can obtain the resources and infrastructure required to scale up innovation and achieve wider social impact by collaborating with MNEs (Arnold et al., 2020; Huybrechts et al., 2017). Hence, networks and partnerships with MNEs are seen as vital in enhancing the commercial legitimacy of SEs, which, in turn, helps them with scaling up social innovation. For example, Novartis, a pharmaceutical company, initiated the Novartis Access Program to provide affordable medicines for non-communicable diseases in low-income countries (Novartis, 2015). It collaborates with various partners, including governments and NGOs, in ensuring that affordable medicines reach underserved populations in developing countries. This suggests that SEs need commercial legitimacy, especially when it comes to achieving the economies of scale needed to sustain their efforts towards social value creation (Lashitew et al., 2022).

SEs that engage in social innovation often face resource constraints, especially concerning finance, management skills, technical expertise, and infrastructure (Mair & Marti, 2009). The extent of such constraints is even greater when the innovation entails higher degrees of sophistication and novelty, which, in turn, may require extensive R&D and well-planned business and marketing strategies, demanding the services of experienced professionals. For example, Hitachi is engaged in social innovation and one of the stories on their website highlights how Hitachi’s technological expertise is used to implement the innovative idea of a poor farmer to remedy the shortage of water in his farm (Hitachi Social Innovation). The extent of any resource constraints is even more prominent in BOPMs (Fajardo et al., 2021; London et al., 2010), potentially resulting in a lack of legitimacy for SEs to commercially pursue their ventures. Hence, they often resort to networking with external partners to address this state of affairs. Thus, we suggest that:

P3b. The greater the level of perceived (i) challenges to the scalability of the social innovation, (ii) novelty, and (iii) sophistication, the greater the likelihood of SEs forming international social alliances with MNEs to acquire commercial legitimacy for their ventures

4 Discussion and Conclusions

In this article, we aimed to provide key insights, from the international business literature and a legitimacy perspective, into the international social alliances established between MNEs and SEs for the design, development, and scaling up of social innovation in BOPMs. Recently, SEs have attracted considerable research attention (Phillips et al., 2015; Rao-Nicholson et al., 2017). However, such enterprises face legitimacy-related challenges as they strive to maintain the delicate balance between their social and commercial goals (Mason & Doherty, 2016; De Silva et al., 2020). MNEs also increasingly face legitimacy challenges while operating in emerging and developing markets, which suffer from weak and underdeveloped institutional infrastructure (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; Peng et al., 2008). In addition, social innovation is associated with social change, which may face societal resistance, also making legitimacy a vital resource for any firm engaging in such ventures. Hence, the establishment of international social alliances between SEs and MNEs can potentially alleviate some of the legitimacy challenges they face as they engage in social innovation in BOPMs (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). Few studies in the international business domain have examined international social alliances from a legitimacy perspective; thus, this conceptual study offers important theoretical and practical insights (Cuypers et al., 2020).

Scholarship suggests that firms face different types of legitimacy-related challenges, with commercial, institutional (informal), and social legitimacy being some of the major ones (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). Legitimacy is also a central notion in institutional theory (Meyer & Scott, 1983; Suchman, 1995). Hence, drawing from the institutional theory and legitimacy literature on SEs, we explored three key forms of legitimacy needed by both MNEs and SEs forging international social alliances to develop social innovations for BOPMs. From the international business perspective, social innovation enacted through alliances provides ample opportunities for MNEs to expand their product and market scope. However, legitimacy plays a significant role in securing the required social acceptance (for new products and services) and addressing the challenges associated with the idiosyncratic norms, traditions, beliefs, and values prevalent in BOPMs. Our focus was on the social, institutional, and commercial legitimacy requirements that can be addressed by international social alliances, which, in turn, are vital for driving social innovation in BOPMs.

In terms of social legitimacy, we argue that institutional voids and underdeveloped intermediaries cause business enterprises to face greater challenges in establishing social legitimacy in BOPMs (Khanna & Palepu, 1997). In such contexts, firms also face trust-related issues, thus, forming social ties with key stakeholders can be important for MNEs to develop legitimacy and overcome any liability of foreignness (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Zaheer, 1995). The pro-social business model and social embeddedness of SEs in BOPMs may provide MNEs with social legitimacy, thus helping them to develop trust with BOPM consumers (Gold et al., 2020; Webb et al., 2010).

Furthermore, firms face institutional legitimacy challenges in BOPMs due to the evolving nature of formal institutions and the important role played by informal ones in helping firms establish institutional legitimacy (Khann & Palepu, 1997, 2000; Webb et al., 2010; Peng, 2003; Wright et al., 2005). As SEs have well-established networks with local actors in BOPMs, any international social alliance formed with them will provide MNEs with the institutional legitimacy they sorely need to overcome any trust deficit in BOPMs. Last, from the SEs’ perspective, we argue that such enterprises will face commercial legitimacy-oriented challenges while driving social innovation, which, in turn, may hinder their growth (Turker & Vural, 2017; Zamantili Nayir & Shinnar, 2020). Such enterprises are establishing dual business models that integrate commercial and social elements (De Silva et al., 2020). Against such a backdrop, SEs face greater challenges to establish their commercial legitimacy; hence, forming international social alliances with MNEs will provide them with the business acumen and infrastructure necessary to scale up social innovation for both base- and top-of-the-pyramid customers (De Silva et al., 2020).

As there has hitherto been a limited examination of the various legitimacy issues confronted by international social alliances across different institutional contexts, our study contributes to understanding the legitimacy-related issues found in international social alliances. The propositions put forward in this paper indicate the context-dependent nature of the legitimacy that firms need when operating in different institutional settings. Therefore, it becomes difficult for organizations to strike a trade-off or balance different legitimacy requirements when dealing with different institutional logic and stakeholder demands.

Thus, our study of international social alliances provides important conceptual insights suited to understanding the different types of legitimacy challenges faced by the partners in such alliances and the social innovation and institutional environment aspects that influence their legitimacy requirements in emerging and developing markets. In doing so, we integrated key insights from the literature on SEs, institutions, and legitimacy to provide a more fine-grained conceptual view of social alliances driving the social innovation enacted in different contexts (Phillips et al., 2015).

4.1 Practical and Policy Implications

By focussing on legitimacy within the international social alliances operating in BOPMs, we provided important implications for practitioners and policymakers. From the practitioners’ perspective, our study has important implications for MNEs, SEs, and NGOs. First, we highlighted the importance of international social alliances between MNEs and SEs about harnessing the unique strengths of each party for mutual value creation. MNEs bring financial resources, global reach, and expertise in scaling operations, while SEs offer a deep understanding of local communities and innovative social solutions. When seeking international social alliances, managers should emphasize that such relationships must offer the strengths and resources that can maximize their collective impact. Specifically, managers should identify partners that can complement their organizations’ capabilities and fill any gaps in their expertise. A shared commitment to a common purpose can strengthen the partnership and enhance its legitimacy. Second, our study indicates that international social alliances promote the building of social, commercial, and institutional legitimacy. In this regard, managers should conduct thorough research and engage with local stakeholders to understand the specific needs and challenges found in the BOPMs they serve. This would help MNEs to work with SEs and tailor initiatives fit to suit the cultural, economic, and social context of the target area, which can, in turn, support legitimacy building. Third, practitioners should educate BOPM consumers about the benefits and proper use of any social innovation introduced by MNEs. This would empower customers to make informed choices suited to improve their quality of life.

From the policymakers’ perspective, understanding the propositions outlined in this study can help in the design of educational and training programs that recognize and support legitimacy-building strategies. These programs can encourage the involvement of SEs, helping them to develop the skills and capabilities necessary to collaborate effectively with MNEs. They can also facilitate knowledge sharing and promote networking events to foster collaboration and learning between different stakeholders. Furthermore, governments and local bodies can offer financial incentives such as grants, subsidies, or low-interest loans to both MNEs and SEs in BOPMs that are engaged in socially impactful projects. These grants could be provided for various purposes, including product development, market research, capacity building, and expansion into underserved areas. For example, subsidies could be provided for energy-efficient technologies, clean water initiatives, or affordable healthcare services. In addition, governments could encourage partnerships between MNEs, SEs, and local communities to ensure that any international social alliances are developed in consultation with those they intend to benefit.

4.2 Limitations and Future Research Agenda

Although our study makes important contributions, it is marred by several limitations that offer avenues for future research. First, we highlighted three key legitimacy concerns from the SEs’ and MNEs’ points of view, identifying a need to examine external environmental influences and legitimacy (e.g., Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), future research could thus explore the impact of different legitimacy challenges on the nature of social innovation and social alliance performance in BOPMs.

Second, future studies could examine the optimal structure of international social alliances the nature of their governance across developed and emerging markets, and the impact of alliance structure and governance on social innovation in BOPMs.

Third, this study’s conceptual nature implies that we did not collect any primary data to test our propositions. Therefore, future studies could empirically test the propositions that we put forward in this study. In doing so, researchers could engage in survey-based comparative research by collecting data from different BOPMs. For example, data could be gathered from BOPMs in Asian, African, and Latin American regions and comparisons could be made to understand the differences in the international social alliances established in different regions.

Fourth, cultural and institutional distances could affect alliance legitimacy in BOPMs, where information asymmetry and uncertainty are pervasive. Future studies could consider cultural and institutional distances as moderators and determine their impact on different types of legitimacy (moral, cognitive, social, internal, and external) within the contexts of international social alliances. Further, the legitimacy requirements for MNEs are constantly evolving, and legitimacy is a perishable resource (Mason, 2012). However, MNEs could face ongoing threats to their legitimacy—e.g., cultural and ethical misalignment, failure to comply with local laws and regulations, and lack of transparency in business practices, among others. Thus, future research could focus on the influence of such threats on developing and maintaining the legitimacy required to drive social innovation in BOPMs. Firms may also require different forms of legitimacy during different stages of social innovation. Hence, they may also trade off one form of legitimacy for another, depending on the stage of innovation and other external influences. The dynamics of power at play in international social alliances could also be dictated by the evolving nature of the legitimacy requirements of the partners involved. Hence, scholars could examine legitimacy as a dynamic concept, thus shedding further light onto many of the aspects discussed above. Such studies could investigate these issues in international social alliances based on developed and emerging/developing markets.

Fifth, although our study highlighted the characteristics of social innovation as a driver of international social alliances, greater attention should be paid to the antecedents of social innovation in BOPMs. Hence, future studies could examine legal, political, financial, social, and technological drivers of social innovation in BOPMs. For example, future investigations could address (i) how legal structures for SEs influence their ability to innovate and scale, (ii) what impact investment funds, microfinance institutions, and venture capital have on social innovation; (iii) how advancements in emerging technologies—such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and renewable energy solutions—are transforming social innovation in BOPMs; and (iv) how legal reforms and political support combine with financial innovations to create an enabling environment for social innovation. Sixth, our framework and its associated propositions provide an important initial reference to examine the multiple types of legitimacy needed by international social alliances operating in BOPMs. Future studies could refine our model and propositions as—due to their broad nature and the context-specificity of different types of legitimacy—they may not be applicable in different institutional settings. Finally, future studies could also pay greater attention to the consequences of social innovation on BOPMs, and it would be interesting to examine both the positive and negative impacts of social innovation on such markets’ consumers and alliance partners.

4.3 Conclusions

International social alliances with SEs have the potential of generating loyalty among target consumers and boosting brand image, both of which have long-term implications for the profitability of MNEs (Rodriguez et al., 2013). The collaboration between Starbucks and NGOs such as Oxfam and the Ford Foundation is one such example (Argenti, 2004). The process whereby these evolve, and the role played by perceptions of legitimacy in enhancing loyalty and brand image need a greater in-depth study aimed at informing appropriate strategies for companies pursuing the social alliance mode.

We highlighted the effects of the market constraints found in BOPMs—due to the lack of adequate institutional environments—on the legitimacy requirements of MNEs in international social alliances. This, especially from an international business perspective, means that MNEs can struggle to understand the nature of consumer demand (with its multiple segments) and expectations, and face additional issues in managing supply chains (El-Tannir, 2019). In addition, such markets’ demand fluctuates periodically, offering little security in terms of continuity. This means that MNEs have to rely on SEs to access the informal institutions and knowledge of local markets. The demand side of BOPMs also challenges MNEs, with highly price-sensitive consumers who are very risk averse, reluctant to switch from existing products/services, and often do not trust the intentions of MNEs. Hence, it is vital for MNEs to attain a social endorsement from SEs and to adopt a frugal approach towards social innovation, focusing on aspects of affordability and attractive price-performance ratios, and embedding the social value of the innovation in their value proposition.

From the international business perspective, this calls for strategies such as the use of social network brokers, who interpret and transfer knowledge across groups, and more conventional forms of buyer-supplier alliance networks that are more concentrated on social activities. As many BOPMs do not have access to emerging technologies, MNEs may have to rely on local networks to build legitimacy and transition from outsidership to insidership. SEs typically employ the strategy of connecting with locals to further gain legitimacy and receive ongoing support and acceptance. It further means that MNEs need to choose, as alliance partners, SEs that are well embedded in BOPM communities, with the high social brand equity and social acceptance that are vital to the success of any social innovation venture.

Social alliances also facilitate the international market orientation of MNEs, as SEs often have a better awareness of the ground realities and act as agents of change regarding consumer tastes and preferences. Scholars have commented that NGOs are better than companies at forming coalitions and can act as change agents in disrupting markets (Argenti, 2004). Tobacco is an example of this. Therefore, international social alliances can enable companies to proactively study the changes taking place in BOPMs. To this end, it is important to manage the legitimacy of such alliances in the eyes of the BOPM consumers and other stakeholders.

References

Adomako, S., & Tran, M. D. (2022). Local embeddedness, and corporate social performance: The mediating role of social innovation orientation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(2), 329–338.

Agarwal, N., Chakrabarti, R., Brem, A., & Bocken, N. (2018). Market driving at bottom of the pyramid (BOP): An analysis of social enterprises from the healthcare sector. Journal of Business Research, 86, 234–244.

Alberio, M., & Moralli, M. (2021). Social innovation in alternative food networks. The role of co-producers in Campi Aperti. Journal of Rural Studies, 82, 447–457.

Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670.

Andersen, P. H., & Esbjerg, L. (2020). Weaving a strategy for a base-of‐the‐pyramid market: The case of Grundfos LIFELINK. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3687–3701.

Anderson, J., & Markides, C. (2007). Strategic innovation at the base of the pyramid. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(1), 83–88.

Angeli, F., & Jaiswal, A. K. (2015). Competitive dynamics between MNCs and domestic companies at the base of the pyramid: An institutional perspective. Long Range Planning, 48(3), 182–199.

Argenti, P. A. (2004). Collaborating with activists: How Starbucks works with NGOs. California Management Review, 47(1), 91–116.

Arnold, M. G., Gold, S., Muthuri, J. N., & Rueda, X. (Eds.). (2020). Base of the pyramid markets in Asia: Innovation and challenges to sustainability. Routledge.

Arranz, N., Arroyabe, M., Li, J., & de Fernandez, J. C. (2020). Innovation as a driver of eco-innovation in the firm: An approach from the dynamic capabilities theory. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1494–1503.

Arslan, A., Buchanan, B. G., Kamara, S., & Al Nabulsi, N. (2022). Fintech, base of the pyramid entrepreneurs and social value creation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 29(3), 335–353.

Barraket, J., Furneaux, C., Barth, S., & Mason, C. (2016). Understanding legitimacy formation in Multi-goal firms: An examination of Business Planning practices among Social Enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 54, 77–89.

Barron, D. N. (1998). Pathways to legitimacy among consumer loan providers in New York City, 1914–1934. Organization Studies, 19(2), 207–233.

Battistella, C., Dangelico, R. M., Nonino, F., & Pessot, E. (2021). How social start-ups avoid being falling stars when developing social innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management, 30(2), 320–335.

Bauwens, T., Huybrechts, B., & Dufays, F. (2020). Understanding the diverse scaling strategies of social enterprises as hybrid organizations: The case of renewable energy cooperatives. Organization & Environment, 33(2), 195–219.

BBC (2014). ‘The Indian sanitary pad revolutionary’ https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-26260978 Accessed on July 2018.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2004). Social alliances: Company/nonprofit collaboration. California Management Review, 47(1), 58–90.

Bertrand, M., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2006). Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 8–23.

Bijoy, C. R. (2006). Kerala’s Plachimada struggle: a narrative on water and governance rights. Economic and Political Weekly, 4332–4339.

Brix-Asala, C., Seuring, S., Sauer, P. C., Zehendner, A., & Schilling, L. (2021). Resolving the base of the pyramid inclusion paradox through supplier development. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(7), 3208–3227.

Cacciolatti, L., Rosli, A., Ruiz-Alba, J. L., & Chang, J. (2020). Strategic alliances and firm performance in startups with a social mission. Journal of Business Research, 106, 106–117.

Ceesay, L. B., Rossignoli, C., & Mahto, R. V. (2022). Collaborative capabilities of cause-based social entrepreneurship alliance of firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 29(4), 507–527.

Chelekis, J., & Mudambi, S. M. (2010). MNCs and micro-entrepreneurship in emerging economies: The case of Avon in the Amazon. Journal of International Management, 16, 412–424.

Choi, N., & Majumdar, S. (2015). Social innovation: Towards a conceptualisation. In Technology and innovation for social change (pp. 7–34). Springer.

Christensen, C. M., Baumann, H., Ruggles, R., & Sadtler, T. M. (2006). Disruptive innovation for social change. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 94–100.

Creed, W. E. D., Scully, M. A., & Austin, J. R. (2002). Clothes make the person? The tailoring of legitimating accounts and the social construction of identity. Organization Science, 13(5), 475–496.

Cuypers, I. R., Ertug, G., Cantwell, J., Zaheer, A., & Kilduff, M. (2020). Making connections: Social networks in international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(5), 714–736.

Dacin, M. T., Oliver, C., & Roy, J. P. (2007). The legitimacy of strategic alliances: An institutional perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 169–187.

Dacin, P. A., Dacin, M. T., & Matear, M. (2010). Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3), 37–57.

Dacin, M. T., Dacin, P. A., & Tracey, P. (2011). Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions. Organization Science, 22(5), 1203–1213.

Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(4), 411–424.

Dau, L. A., Chacar, A. S., Lyles, M. A., & Li, J. (2022). Informal institutions and international business: Toward an integrative research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(6), 985–1010.

De Silva, M., Khan, Z., Vorley, T., & Zeng, J. (2020). Transcending the pyramid: Opportunity co-creation for social innovation. Industrial Marketing Management, 89, 471–486.

Decker, S., & Obeng Dankwah, G. (2023). Co-opting business models at the base of the pyramid (BOP): Microentrepreneurs and multinational enterprises in Ghana. Business & Society, 62(1), 151–191.

Dembek, K., & York, J. (2022). Applying a sustainable business model lens to mutual value creation with base of the pyramid suppliers. Business & Society, 61(8), 2156–2191.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Dionisio, M., & de Vargas, E. R. (2020). Corporate social innovation: A systematic literature review. International Business Review, 29(2), 101641.

El Baba, W., & Fakih, A. (2023). COVID-19 and consumer behavior: Food stockpiling in the US market. Agribusiness, 39(2), 515–534.

El-Tannir, A. A. (2019). A supplier strategy to Control the Bullwhip Effect. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(2), 498.

Esposito, P., Doronzo, E., & Dicorato, S. L. (2022). The financial and green effects of cultural values on mission drifts in European social enterprises. Business Strategy and the Environment, Forthcoming.

Fajardo, X. R., Arnold, M. G., Muthuri, J. N., & Gold, S. (Eds.). (2021). Base of the pyramid markets in Latin America: Innovation and challenges to sustainability. Routledge.

Foreman, P., & Whetten, D. A. (2002). Members’ identification with multiple-identity organizations. Organization Science, 13(6), 618–635.

Gigliotti, M., & Runfola, A. (2022). A stakeholder perspective on managing tensions in hybrid organizations: Analyzing fair trade for a sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment.

Gillett, A., Loader, K., Doherty, B., & Scott, J. M. (2019). An examination of tensions in a hybrid collaboration: A longitudinal study of an empty homes project. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(4), 949–967.

Gold, S., Chowdhury, I. N., Huq, F. A., & Heinemann, K. (2020). Social business collaboration at the bottom of the pyramid: The case of orchestration. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(1), 262–275.

Gold, S., Arnold, M. G., Muthuri, J. N., & Rueda, X. (Eds.). (2021). Base of the pyramid markets in affluent countries: Innovation and challenges to sustainability. Routledge.

Gözübüyük, R., Kock, C. J., & Ünal, M. (2020). Who appropriates centrality rents? The role of institutions in regulating social networks in the global islamic finance industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(5), 764–787.

GSK (2023). A lifesaving partnership. https://www.gsk.com/media/5379/save-the-children-partnership-brochure.pdf.