Abstract

Despite growing concern in the social innovation (SI) literature about the tackling of grand challenges, our understanding of the role of multinational enterprises (MNEs) remains in its infancy. This article examines foreign MNE subsidiaries’ SI investments focusing on United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) in host countries. Using financial data from large, listed subsidiaries of foreign MNEs operating in India, along with hand-collected data from firms’ disclosures of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activity for five years starting in 2015, we utilise the externalities framework propounded by Montiel et al. (2021). This neatly translates the 17 UNSDGS into actionable goals to examine the efforts of foreign MNE subsidiaries in increasing positive externalities as opposed to reducing negative externalities via SI-related investment in host countries. The study also evaluates the effects of the local embeddedness of the foreign MNE subsidiaries on SI investment. We find that MNE subsidiaries tend to favour increasing positive externalities as compared to reducing negative externalities through their SI investments. Also, older subsidiaries tend to prioritize greater investments in SI projects related to reducing negative externalities and subsidiaries with higher MNE ownership tend to reduce investments in SI projects related to increasing positive externalities. We discuss possible interpretations of the exploratory results using the institutional logics perspective and conclude with implications for policy and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Societal grand challenges (e.g. poverty, hunger, migration, climate change) are receiving increasing attention from international business (IB) scholars primarily focusing on the role of MNEs because they “…transcend geographic, economic, and societal borders, and are therefore multinational by nature” (Buckley et al., 2017, p. 1046). Although government plays a pivotal role in implementing important international manifestos, MNEs are well-poised to take a central role in handling grand challenges given their global resources and capabilities, transfer of cutting-edge technologies and increasing emphasis on corporate CSR (Ajwani-Ramchandani et al., 2021; Eang et al., 2023; Sachs & Sachs, 2021). It has been repeatedly opined that without the active participation and commitment of MNEs, it will be impossible to tackle these grand challenges at scale (Ghauri & Cooke, 2022, p. 330; Witte & Dilyard, 2017). Additionally, it is important to note that MNEs are also under strong pressure from multiple stakeholders to balance their profit motive with wider societal needs.

In the IB literature, one of the areas requiring urgent attention is empirical investigation and validation of SI contributions by foreign MNE subsidiaries in host countries to the tackling of grand challenges. SI is defined as “…a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable, or just than existing solutions and for which the value created accrues primarily to society as a whole rather than private individuals” (Phills et al., 2008, p. 36). It has entered both academic as well as public discourses in recent years but, despite a vast body of literature focusing on the contribution of not-for-profit organisations, few scholars have attempted to understand the involvement of for-profit firms in SI using a case study approach (Altuna et al., 2015; Foroudi et al., 2021; Herrera, 2015; Molloy et al., 2020).

Although MNEs have been heavily criticised in the past for their negative environmental and social impacts in host countries (Giuliani & Macchi, 2013), it has been argued that we need to empirically examine and acknowledge their positive contributions to local communities through SI that help reduce economic inequality, attain social development and protect environmental resources (Dionisio & de Vargas, 2020). It is believed that firms with greater focus on SI may have a more positive societal impact (Lee et al., 2019), but there is still a complete dearth of empirical evidence focusing on the SI activities of subsidiaries of foreign MNEs in developing countries. It was recommended by Jones et al. (2016) that to achieve SDGs, MNE should actively work towards increasing positive externalities and reducing negative ones. Building upon these arguments, in this paper we examine the research question “whether MNEs choose SI projects which lead to increasing positive externalities or reducing negative externalities”. Connectedly, we also examine the conditions that impact this selection.

Adopting the externalities framework proposed by Montiel et al. (2021) based on the 17 UNSDGs, through this study we examine the SI investments of subsidiaries of foreign MNEs to compare whether they focus on improving positive externalities (e.g. knowledge, wealth and health) as opposed to reducing negative externalities (e.g. overuse of natural resources, harm to social cohesion and overconsumption) in developing countries. Increasing positive externalities involves society receiving incremental benefits from the activities of a firm without any ensuing payment, while reducing negative externalities relates to stakeholders suffering less due to the activities of a firm. Given these definitions, we propose that MNE subsidiaries choose investments in projects related to increasing positive externalities when they are following the market logic and choose investments in projects related to reducing negative externalities when they are following the community logic. We build this argument given the nature of the UNSDGs and associated projects defined as impacting positive or negative externalities.

There seems to be a consensus among IB scholars that a subsidiary’s local embeddedness plays a key role in its for-profit innovation endeavours (Meyer et al., 2011). However, we have limited evidence explaining why subsidiaries differ in terms of their SI investment. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the role played by the local embeddedness of foreign MNE subsidiaries in the context of SI for two reasons. First, we argue that higher local embeddedness of subsidiaries will improve their understanding of host country social issues as well as the challenges faced by key stakeholders, resulting in increased investments in SI. Second, the current literature posits that MNEs need access to local resources as well as partnerships in the host country in order to innovate (Andersson & Forsgren, 1996). Therefore, we posit that subsidiaries with higher local embeddedness will invest more in SI. More specifically, based on an in-depth literature review of IB literature, a subsidiary’s degree of local embeddedness measured by longer presence in host country (Foss & Pedersen, 2002; Rabbiosi & Santangelo, 2013; Williams & Du, 2014) and higher equity participation by local actors (Andersson & Forsgren, 1996; Bell et al., 2012) are hypothesised as key determinants of SI investments to increase positive and reduce negative externalities.

Our research contributes to the rapidly emerging literature on SI by exploring the role played by MNE subsidiaries in resolving societal grand challenges through investment in SI to improve positive externalities as well as reduce negative externalities in developing countries. Further, we argue that local embeddedness of MNE subsidiaries through higher local ownership and/ or longer presence in host countries will result in more SI spend. The contextual background for our study is the provision in the Companies Act 2013 that mandates large firms in India to spend at least 2% of their average net profits from the previous three years on socially beneficial projects (further details are given in the methods section), which constitutes a unique research settings for several reasons. This is the first and one of the unique laws in the world that mandates companies to spend for greater social advantage. Second, the act provides a list of mandated SI activities aligned with UNSDGs (Balon et al., 2022). Third, it forces firms to go beyond charitable donations by actively pursuing SI projects that help tackle societal challenges. We interpret our results using the institutional logics perspective (Thornton et al., 2012), which is our main theoretical contribution. The institutional logics perspective can be regarded as being within the wider institution-based view framework (Peng et al., 2023), being part of “one of most prominent schools of thought within organization studies at present” (Alvesson & Spicer, 2019, p. 199). Consequently, we are responding to the call that “a deepening and broadening the institution-based view is a must” in order to advance our understanding of how companies can help in the response to grand challenges (Peng et al., 2023).

2 Literature Review

2.1 Social Innovation

The disparate nature of the field of SI is reflected in it being described as a ‘container concept’ with no fixed definition (Edwards-Schachter et al., 2012; Lind et al., 2018). Thus, in addition to the definition above, SI has been variously defined as:

-

“concerned with innovations that are social both in their ends and in their means” (Mulgan, 2019, p. 113),

-

“a measurable, replicable initiative that uses a new concept or a new application of an existing concept to create shareholder and social value” (Herrera, 2015, p. 1469),

-

“the process in which an external social enterprise, originating in a different institutional context, enables embedded agency on the part of local communities” (Venugopal & Viswanathan, 2019, p. 801).

A systematic literature review of Corporate Social Innovation (CSI) was conducted by Dionisio and de Vargas (2020), who looked at how the concept of CSI has evolved and how it differs from other similar concepts such as CSR. They considered that CSR is more focussed on philanthropic initiatives mainly aimed at improving corporate reputation whereas CSI is a strategic alliance between companies and the social sector which applies energies to both solve the chronic problems of society and powerfully stimulate the business’ own development (Kanter, 1999).

Schumpeter (1934) can be considered as one of the most influential theorists to describe how continual innovation within the economy gave rise to creative destruction and new opportunities. The related field of innovation studies has grown since the 1950s with the work of business academics such as Rosemary Kanter, Gary Hamel and Clayton Christensen looking into patterns of innovation, especially the problems involved in the early stages (Mulgan, 2019). An interesting twist is the concept of reverse innovation, which describes innovations originating in emerging contexts which then spread to more advanced ones (Immelt et al., 2009). Usually considered to be a relatively new phenomenon (von Janda et al., 2018), Govindarajan & Ramamurti, (2011) argued that developed country MNEs have always had the technical capabilities needed to develop products for emerging markets, but have not had the incentive to do so. This leaves an opportunity for local firms, but these may be hampered by a lack of the resources needed for product innovation, termed the ‘deficiency problem’ (Lim et al., 2013). Consequently, emerging market MNEs may have a competitive advantage since they do not suffer from such deficiencies and additionally have an awareness of local needs and so can take advantage of the ‘reverse innovation saga’ (Vadera, 2020). This marks the coming of age for affordable innovations and illustrates how both institutional voids and very low levels of per capita income demand a fundamental redesign of MNEs’ organisation design and business model (Sarkar, 2011).

The connections between reverse innovation and SI have been explored by Cannavale et al. (2021), since “innovations, whose primary goal is to suit customers’ social needs and enable to improve the wellbeing, are known in the literature as social innovation” (2021, p. 425). However, the history of SI can be considered to stretch “at least as far back as the cooperative and social business movements of the Victorian era (McGowan & Westley, 2015) but of course in a general sense SI is as old as civilisation itself” (Tracey & Stott, 2017, p. 57). Consequently, there is a case to be made for considering business innovation, whose motivation is financial profit, to be separate from social innovation, whose motivation is social, although there is undeniably an area of overlap.

For innovation to be social, local factors need to be considered as opposed to change being imposed from above in a blanket fashion. Steinfield and Holt (2019) take this perspective to develop a theory of the reproduction of SI in subsistence marketplaces with three modes – mimetic, facilitated and complex. Important factors are not only the attributes of the innovation, but also the knowledge and resources of local actors including bridging agents. This importance of the local context was also stressed by Venugopal and Viswanathan (2019) who argued that SI implementations in subsistence marketplaces often fail because they do not take the specifics of local communities into account. They contend that a process of ‘facilitated institutional work’ is needed whereby SI organisations need to legitimate themselves within local communities before disrupting aspects of the local institutional environment. They then need to help re-envision institutional norms or practices whilst resourcing the institutional change process. Institutions here are taken to be “’rules of the game’ that are evolved by humans in order to guide collective behaviour and reduce uncertainty in human exchange (North, 1990)” (Venugopal & Viswanathan, 2019, p. 803) and so clearly the local ‘rules of the game’ need to be taken into account before meaningful change can be brought about.

This emphasis on the importance of local factors illustrates the need for a corresponding theoretical foundation which is provided by the institutional logics perspective, which will now be reviewed.

2.2 Institution-Based View and the Institutional Logics Perspective

There are a number of standpoints by means of which international business and strategic management can be viewed and the institution-based view has increasingly been seen as a leader in this regard (Buckley et al., 2023; Meyer & Peng, 2016; Peng et al., 2023). Its strengths are “its quest for dynamic rather than static explanations of firm behavior, and its embrace of interdisciplinary approaches” (Peng et al., 2023, p. 353), including new institutional economics and MNE-government bargaining in IB (Meyer & Peng, 2016). This enables a cross-fertilisation of ideas across scholarly disciplines and brings insights “above and beyond those gained from firm-focused or actor-focused theories such as resource-based view and agency theory” (Meyer & Peng, 2016, p. 20). These facets, together with its broad scope and integrative and inclusive nature (Peng et al., 2023), mean that it can be regarded as being particularly appropriate for our current purposes. Alternative perspectives such as the industry and resource-based views have been criticised for their lack of attention to contexts (Peng et al., 2023), discounting the formal and informal institutions that provide much of the context of competition (Buckley et al., 2023; Kostova et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2008). Furthermore, these views were developed primarily in the context of the United States, where a relatively stable institutional framework applies equally across the board. However, this is not the case in an international context, especially for emerging economies such as our study context of India which presents a dynamic environment exemplified by the mandated change brought about by the Companies Act 2013. Consequently, we prefer in this instance to take an institution-based approach to interpret our results.

Within the overall framework of the institution-based view, the institutional logics perspective has come to be recognised as a leading perspective to analyse organisations subject to different institutional logics (Pache & Santos, 2013; Peng et al., 2023) and so it is especially apposite to current purposes. The institutional logics perspective (Thornton et al., 2012) has become a key concept (Gümüsay et al., 2020), proposing that society is composed of competing yet interdependent institutional orders – the family, community, religion, state, market, profession and corporation. With striking similarities to Max Weber’s concept of value spheres (Weber, 1920/1958), each institutional logic is made up of principles, such as sources of authority and identity, which organize and shape the interests and preferences of individuals and organizations, how they are likely to understand their sense of self and identity, how they act and their vocabularies of motive and salient language (Thornton et al., 2012). Thus, each logic has its own rationality and presents its own unique view of reality (Thornton et al., 2012). Consequently, action within each logic is “oriented towards determinate, incommensurable, ultimate values: divine salvation in religion, aesthetics in art, power in politics, property in capitalist markets, erotic love, knowledge in science” (Friedland, 2013, p. 5).

Organizations as well as individuals, are subject to multiple institutional logics (Greenwood et al., 2010) which may be competing or cooperating (Kraatz et al., 2020). As a result, institutional logics lead to distinctive forms of organisation in order to pursue the substances that motivate them (Mutch, 2021, p. 14). This is especially relevant for organizations such as MNE subsidiaries, which are particular instantiations of the corporation logic, operating in countries different from those of the parent since the institutional environment in the host country may differ significantly from that of the parent company. The subsidiary will commonly be expected to pursue profit and not social goals, which may therefore present a particular challenge for SI initiatives. Nevertheless, several studies emphasise the importance of the community logic in this regard. For example, Venkataraman et al. (2016) described how a NGO successfully improved social and economic conditions of women and families in rural India using a combination of market and community logics. Similarly as described above, Venugopal and Viswanathan (2019) argued that many SI implementations fail because they do not pay enough attention to the local ‘rules of the game’ which are part of the community logic. Consequently, the institutional logics perspective can be argued to be a useful perspective to use when considering how commercial organisations interact with non-market situations such as SI initiatives.

In sum, MNE subsidiaries face multiple seemingly conflicting logics. They are influenced by the market logic and the corporation logic from the parent company, as well as the state logic based on the laws and regulations in the host country in which they operate. We argue that in the case of India with the new regulations, the market logic needs to be managed together with the state logic. In addition, MNE subsidiaries are also influenced by the local community logic in the host country. This community is comprised of the people living next to operational sites, consumers, employees and local media among others. As a result, the choice of the SI projects by the MNE subsidiary may be impacted by a number of logics – those of the community, corporation, market and state.

2.3 UNSDGs, MNEs and Externalities

To help addresses grand challenges, in 2015 the 193 members of the United Nations formulated the 2030 agenda with 17 SDGs that are intended to “…stimulate action over the next 15 years in areas of critical importance for humanity and the planet” (UN General Assembly, 2015, p. 3). The 17 SDGs are (1) no poverty, (2) zero hunger, (3) good health and well-being, (4) quality education, (5) gender equality, (6) clean water and sanitation, (7) affordable and clean energy, (8) decent work and economic growth, (9) industry, innovation, and infrastructure, (10) reducing inequalities, 11) sustainable cities and communities, 12) responsible consumption and production, 13) climate action, 14) life below water, 15) life on land, 16) peace, justice, and strong institutions and 17) partnerships for the goals. These 17 SDGs present a broad range of environmental, economic and social goals that can be applied in all countries.

Despite multiple calls for IB scholars to prioritise these 17 SDGs in their research agenda (e.g., George et al., 2016; Liou & Rao-Nicholson, 2021; Montiel et al., 2021), the path is still not well-defined or empirically validated considering that these SDGs are espoused as country-level goals rather than firm-specific objectives. However, SDGs can act as lingua franca to bridge the disconnect emerging between MNEs, government, non-governmental agencies and society that potentially share common development objectives. SDGs can also help MNE managers to identify, classify and prioritise specific goals better aligned with firm mission and vision, as well as to work more closely with network partners that share similar aspirations for societal change (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2022; Gehringer, 2020). According to a report by PwC (2019), almost three quarters of the world’s largest companies have contributed to the SDGs demonstrating significant commitment by MNEs worldwide.

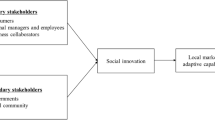

To further clarify the role of MNEs in achieving the UNSDGs, Montiel et al. (2021) propounded the concept of externalities as an important tool for social value creation and proposed a framework wherein these 17 SDGs are neatly divided into six broad categories, viz. (1) increasing knowledge (#4 and #9), (2) increasing wealth (#1, #5 and #8) and (3) increasing health (#2 and #3), (4) reducing the overuse of natural resources (#6, #7, #13 and #15), (5) reducing harm to social cohesion (#10, #11, #16 and #17) and (6) reducing overconsumption (#12 and #14) (see Fig. 1).

Positive and negative externalities adapted from Montiel et al. (2021)

Past studies have reported on the multifaceted role played by MNEs in the reduction of negative externalities aligned with UNSDGs, for example #6) tackling ground water depletion issues in local communities (Shapiro et al., 2018), #7) transitioning to renewable energy (Erin Bass & Grøgaard, 2021), #10) creating skilled jobs for local people (Jackson, 2014), #11) investing in the development of sustainable cities (Ordonez-Ponce & Talbot, 2023), #12) adopting eco-friendly technology in manufacturing value chains (Attah-Boakye et al., 2022), #13) influencing climate policies by working closely with governmental and non-governmental institutions (Kolk & Pinkse, 2008), #14) promoting sustainable tourism (Hatipoglu et al., 2019), #15) preserving land and water ecosystems (Rondinelli & Berry, 2000), #16) working proactively and positively with host country institutions to combat corruption (Keig et al., 2015) and #17) promoting access and usage of quality financial services especially among disadvantaged groups (Úbeda et al., 2023).

On the other hand, to increase positive externalities MNEs can take multifaceted actions such as #1) actively working towards poverty reduction and sustainable development in host countries (Ghauri & Wang, 2017), #2) contributing to food security and farm technology (Santangelo, 2018), #3) raising awareness of health issues and investing in public as well as private health infrastructure (Yang et al., 2012), #4) participating in vocational education and training to enable access to education in host countries (Dunning & Fortanier, 2007), #5) enabling female empowerment by partnering with micro-finance institutes (Terpstra-Tong, 2017), #8) collaborating with SMEs for balanced economic growth (Sinkovics et al., 2021) and #8) fostering innovation capacities especially in marginalised communities (Liou & Rao-Nicholson, 2021).

2.4 MNE Investments in SDGs for SI

Within the IB literature focusing on efforts by MNEs to tackle grand challenges by investing in SDGs, some recent studies investigated interesting aspects such as the involvement of MNE subsidiaries with local communities (Eang et al., 2023), energy transition (Erin Bass & Grøgaard, 2021), social value creation (Rygh, 2019), employee identification with sustainability initiatives (Munro & Arli, 2019), innovation ecosystem development (Nylund et al., 2021), partnership with small and medium-sized enterprises (Sinkovics et al., 2021), circular economy (Ajwani-Ramchandani et al., 2021), corporate sustainability reporting (Whittingham et al., 2023), natural resource consumption (Shapiro et al., 2018), green patents (van der Waal et al., 2021), food waste (de Visser-Amundson, 2022) and categorization of MNE roles by their impact on people, the planet, prosperity and peace (Kolk et al., 2017).

Montiel et al. (2021) espoused two types of possible investments by MNE subsidiaries in host countries, (1) internal investment in primary stakeholders with whom the subsidiary has an explicit contractual relationship (e.g. suppliers and employees) and (2) external investment in secondary stakeholders that will benefit from the firm’s voluntary actions (e.g. public interest groups, non-governmental organisations and local communities). One of the ways in which MNEs can help the host country to achieve SDGs is by channelling their external investment spend via CSR into various SI activities (Díaz-Perdomo et al., 2021). Here, “enterprises are encouraged to adopt a long-term, strategic approach to CSR, and to explore the opportunities for developing innovative products, services and business models that contribute to societal wellbeing and lead to higher quality and more productive jobs” (European Commission, 2011, p. 8). Eichler and Schwarz (2019) conducted a systematic literature review of 225 articles and found that almost 90% of the SI case studies on MNEs can be clearly mapped to one or several SDGs and concluded that SDGs can form a robust categorization system to map the SI activities of firms. An in-depth literature review (see Appendix A) suggests that IB scholars are increasingly using the framework propounded by Montiel et al. (2021) to understand the contribution by MNEs to achieving UNSDGs across different contexts. However, there is a clear paucity of empirical evidence investigating the CSR spend for SI activities by MNEs aligned with the concept of externalities (Montiel et al., 2021).

It has been well established within the IB literature that MNE subsidiaries often pursue country-specific investment strategies that are based upon their country of origin (Newenham-Kahindi, 2015), industry sector (Singh & Rahman, 2021), host country environment (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018) and often aligned with their parent company (Liou & Rao-Nicholson, 2021) to increase positive and reduce negative externalities. In this regard, it has been proposed that investment in positive externalities can help MNEs build a stronger competitive advantage (Montiel et al., 2021). For example, a study of the vision and mission statements of MNEs from Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) by Ali et al. (2018) found that Indian firms focus strongly on increasing positive externalities, such as industrial innovation and infrastructure, decent work and economic growth, compared with reducing negative externalities. However, Ordonez-Ponce and Talbot (2023) investigated the sustainability practices of multinationals from China and developed countries and found a significant focus by developed countries MNEs on reducing negative externalities such as poverty reduction, empowerment through education and investment in health facilities. Similarly, while investigating European and North American MNEs, van Zanten and van Tulder (2018) found that MNEs engage more with SDGs that “avoid harm” than those that “do good”. Overall, in the absence of any empirical evidence but considering that emerging economies like India with stronger economic growth demand higher investment in SI activities that increase positive externalities compared with reducing negative ones, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1

MNE subsidiaries will invest significantly higher CSR spend for SI activities to increase positive externalities rather than to reduce negative externalities in host countries.

2.5 Local Embeddedness of Foreign MNEs and SI

In order to accomplish their business and non-business objectives, foreign MNE subsidiaries interact with a host of internal and external stakeholders including local customers, suppliers, distributors, institutions, non-governmental organizations, media agencies, employees, competitors, investors and regulators (Crilly, 2011; Park & Ghauri, 2015; Reimann et al., 2012). Consequently they need not only to understand the local culture but also build relationships for innovation that is relevant in the host country context (Almeida & Phene, 2004). In simpler words, it is imperative for foreign MNE subsidiaries to strongly embed in the local environment, not only to acquire resources but also to build stronger local ties for locally meaningful SI.

Scholars have argued that the local embeddedness of a foreign MNE subsidiary plays a crucial role in influencing its performance, innovation and competence development (Andersson et al., 2002; Gulati et al., 2000; Isaac et al., 2019; Rowley et al., 2000). Furthermore, past studies have also demonstrated that local embeddedness significantly influences subsidiary strategy making (Andersson & Forsgren, 2000). It has been posited that embeddedness not only helps improve subsidiaries’ capacity for absorbing local knowledge in dynamic host country environments (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998), but also augments their innovation activities due to close ties with local networks (Andersson et al., 2005).

Subsidiaries operating in host countries over time develop their local networks and connections, thus creating local embeddedness. In other words, the longer the subsidiary operates in a host country, the greater the local embeddedness of the MNE in the host country. The IB literature has established that subsidiary age captures the experience of the subsidiary in the host country and acts as an important indicator of organizational experience and hence learning based on local knowledge (Birkinshaw & Hood, 1998; Luo & Peng, 1999).

The knowledge gained through this experience enables the subsidiary to understand local challenges and issues, both business and social and cultural. This nuanced knowledge of local, social and cultural aspects is not available to new firms and especially not to newer foreign owned subsidiaries. It has long been argued by management scholars that relatively new subsidiaries of foreign MNEs operating in a host country suffer not only from the liability of foreignness (Zaheer, 1995) but also from the liability of newness. Relatively old subsidiaries are expected to develop assimilated knowledge to innovate in the local conditions (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Rabbiosi & Santangelo, 2013). Foss and Pedersen (2002) have shown that as older subsidiaries have a longer establishment and operational history, they tend to enjoy more autonomy and engage in more innovation compared with their younger counterparts. Also, as older subsidiaries have accumulated experience over a longer period, parent companies often perceive less risk and grant them more autonomy (Garnier, 1982; Raziq et al., 2013). Furthermore, older MNE subsidiaries will also have developed stronger ties with their local partners over a longer period of time (Williams & Du, 2014) providing a stronger foundation for collaborative innovation. Overall, IB scholars have well established that the local experience accumulated by subsidiaries over time results in greater localised efforts and innovation related to localised products and processes (Almodóvar & Nguyen, 2022; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Luo & Peng, 1999; Williams & Du, 2014).

In the context of SI, we argue that compared to younger firms, older MNE subsidiaries have had more time to embed in the host country, consequently providing a stronger accumulated knowledge base of local contexts through the sharing of experiences with multiple local stakeholders (Benito & Gripsrud, 1992). This culminates in better knowledge and awareness of key social challenges and greater investment in SI projects in host countries. Similarly, as argued by Foss and Pedersen (2002), since older subsidiaries are well-established compared to younger ones, they will have more opportunity to engage in locally relevant SI projects, since they possess more autonomy and resources accumulated over time. In a similar vein, since IB scholars have long established the role of trusted local partners augmenting for-profit innovation activities of foreign MNE subsidiaries (e.g., Du & Williams, 2017; London & Hart, 2004), we argue that MNE subsidiaries in emerging economies can use this well-established local partnership network to make much-needed social changes by investing in locally relevant SI projects. Overall, in the face of a lack of prior studies and evidence concerning investments to increase positive versus reducing negative externalities, we hypothesize that older subsidiaries will spend on both externalities to help tackle grand challenges. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2a

Older subsidiaries are associated with higher investments in positive externalities.

Hypothesis 2b

Older subsidiaries are associated with higher investments in negative externalities.

MNE subsidiaries are dually embedded both in the parent MNE as well as in the host country environment (Andersson & Forsgren, 1996). However, greater embeddedness in one of the environments reduces the ability of the subsidiary to embed in the other (Andersson & Forsgren, 1996). In other words when the subsidiary is embedded in the parent environment, the subsidiary is less embedded in the host country and the local environment.

One mechanism through which a subsidiary could gain embeddedness in the host country environment is through equity participation by local actors. In turn, these local actors may provide the required local networks and thus local host country embeddedness. Consequently, MNE subsidiaries, which are part of a cross-border joint venture for example, may achieve local embeddedness through the local partner.

Specifically, in the context of listed subsidiaries of foreign MNEs, local embeddedness could be achieved through the sharing of equity through local stock exchanges (Bell et al., 2012). This embeddedness could result in superior understanding of host country challenges and therefore result in increased SI investment. Due to local listing of shares, foreign MNE subsidiaries may have better access to host country knowledge and resources via local investors, the board of directors and other institutional actors such as regulators. We argue that such local actors help the subsidiary to develop external ties providing improved access to resources that would otherwise be out of the reach of the subsidiary. In addition, listing on local stock exchanges will also mandate inducting eminent executive and non-executive independent members onto the board of directors who can enable better access to local institutional practices, knowledge and networks. These eminent local actors would also act as a source of networks through their own board interlocks - in other words enhancing the subsidiary’s access to local networks. The local knowledge and networks provided to a locally listed subsidiary may also enable a foreign MNE subsidiary to better understand social issues faced by local communities and so invest in SI projects that help increase positive externalities and/ or reduce negative externalities in host countries.

From the perspective of pressures from various stakeholders, a locally listed subsidiary may have to engage in socially relevant investments which in turn may lead to SI. Media scrutiny and institutional requirements may also mandate socially relevant investments from foreign MNEs. Being locally listed may create the expectation by media, governmental institutions, local investors and not for profit organizations that subsidiaries of foreign MNEs need to contribute to overall societal development and therefore invest in socially relevant projects. These projects in the context of resource deficient emerging markets such as India, may result in socially relevant innovation. In the context of India, the federal government expects that private organizations may be better suited to make social investments thereby reducing government driven investments. Legal requirements to not just invest but also implement such requirements force MNE subsidiaries to bypass the inefficiencies of local government institutions in implementing social change. The expectation is that the superior managerial prowess of these non-governmental foreign actors results in greater return from such investments.

However, a subsidiary with lower levels of local embeddedness resulting from reduced local ownership, or in other words higher levels of parent ownership, will have reduced understanding of local institutional and social requirements. The reduced participation by local actors could result in limited embeddedness in the local environment. The higher parent embeddedness through greater parent ownership would in turn create the condition that the subsidiary is embedded in the MNE’s network to a greater extent compared with the local environment (Andersson & Forsgren, 1996). Therefore, a subsidiary which has greater embeddedness in the parent organization would be less inclined to invest in SI projects in the host country. However, in the absence of any empirical evidence concerning the effect of local embeddedness of foreign MNE subsidiaries on SI investment, we posit that:

Hypothesis 3a

Higher parent ownership is associated with lower investments in positive externalities.

Hypothesis 3b

Higher parent ownership is associated with lower investments in negative externalities.

3 Methods

3.1 Context

India was the first country in the world to mandate that large companies (based on a definition of size where the firm met at least one of three requirements in any financial year, viz., 1) net worth of INR 500 crore ~ USD 60 million or more, 2) turnover (total sales) of INR 1,000 crore ~ USD 120 million or more or 3) a net profit of INR 5 crore ~ USD 660,000 or more - based on the exchange rate 1 USD = INR 82.80) spend at least 2% of average net profits (from the preceding three years) on socially beneficial activities by enacting Sect. 135 of the Companies Act 2013 (hereafter referred as the Act). The Act defines a socially beneficial activity as one that serves societal needs such as gender equality, poverty reduction, child mortality reduction, vocational skill enhancement etc. In other words, the Act allows for the alignment of the UN SDG goals and those identified by the Sect. 135. Furthermore, the Act also mandates that, rather than simply transferring funds in the form of donations to charitable causes, firms must use their resources to actively implement socially value accretive projects. Consequently, charitable financial donations are not considered to comply with the Act (Bansal et al., 2021). It is to be noted that under the Act, companies which fail to comply with the provisions relating to CSR expenditure must explain in their annual report the reasons for reduced expenditure and failure to comply with the provisions is punishable by a penalty equal to twice the unspent amount or Rs. 1 crore, whichever is less (Beloskar & Rao, 2022). It has been observed that many firms have spent more than the minimum amount on CSR activities (Beloskar & Rao, 2022). In addition, the Act also mandates an impact assessment of CSR spend on social activities by independent agencies. CSR related disclosures to be made in the annual financial report include details of the CSR policy and the CSR initiatives undertaken during the year.

This presents a unique research setting for several reasons. First, this unprecedented law mandates companies to spend on CSR. Second, this law provides a list of mandated SI activities which are aligned with UNSDGs. Third, it mandates companies to pursue SI projects and not rely on charitable donations to non-governmental agencies. Lastly, the law also mandates an impact assessment of the CSR spend to be carried out by independent agencies. CSR related disclosures made in annual financial reports include details of CSR policy and the CSR initiatives undertaken during the year. These mandatory disclosures form the basis of our dataset for analysis.

3.2 Data

The sample was created using locally listed subsidiaries of foreign (non-Indian) MNEs. Whilst this phenomenon is uncommon in developed countries, it is not unique to India. For example, in addition to India, subsidiaries of Nestle are listed in Malaysia and Nigeria. Similarly, Unilever subsidiaries are listed in India, Pakistan and Indonesia. Abbott, GSK, and ABB also have multiple subsidiaries which are locally listed in different countries. We started with the most frequently traded MNE subsidiaries in India. We used the websites of the largest stock exchanges in India - BSE (formerly known as the Bombay Stock Exchange) and NSE (National Stock Exchange) - to identify these companies. NSE has a NIFTY MNC index which was of particular interest to us. To maintain consistency among the companies and their CSR projects we restricted the sample to manufacturing companies. We had to also restrict our sample to subsidiaries with listed (publicly held) parent companies, so that we could calculate parent size, which we used as a control for parent effects in our analyses.

We finally had data on 41 subsidiaries from 35 parents from the years 2015 to 2019. The law was enforced in 2014 and 2015 was the year of the first annual reports published by the companies containing the CSR details which we needed to classify based on the framework from Montiel et al. (2021). We restricted our data collection period to end in 2019 to avoid any possible impact of Covid-19 on CSR spending. There are a total of 61 subsidiaries of foreign owned MNEs in India listed on the BSE500, which covers the largest 500 companies based on market capitalization. However, shares of all the BSE500 companies are not traded equally. The 41 subsidiaries in our sample were the top 41 traded companies of these 61, thus giving us approximately two thirds coverage of the possible universe of subsidiaries. Restricting our sample to those firms which were highly traded ensured that these subsidiaries published their annual reports consistently and that these reports were available publicly.

3.3 SI Related Variables

The amount of money invested in CSR projects as a proportion of the total sales was calculated as CSR Intensity, which was used as the dependent variable in model 1 to test hypothesis 1.

We identified the amount invested in different projects and each of the projects was then identified as relating to either increasing positive externalities or reducing negative externalities. To test hypotheses 2a and 3a, we calculated the amount invested by the subsidiary in projects relating to increasing positive externalities as a proportion of total CSR investments. We refer to this variable as the Positive CSR Intensity (Positive CSR Int.). We use Positive CSR Int. as the dependent variable in model 2. In this vein, to test hypotheses 2b and 3b we calculated the amount invested by the subsidiary in projects relating to decreasing negative externalities as a proportion of total CSR investments. We refer to this variable as the Negative CSR Intensity (Negative CSR Int.). We use Negative CSR Int. as the dependent variable in model 3.

If the company invested in SI projects relating to increasing positive externalities, we coded a dummy variable – Positive Externalities Investments - as 1 and otherwise 0. Similarly, if the company invested in SI projects relating to decreasing negative externalities, we coded a dummy variable – Negative Externalities Investments - as 1 and otherwise 0. We used these variables to test hypothesis 1.

3.4 Subsidiary and MNE Related Variables

We used CMIE Prowess to calculate the subsidiary level variables. CMIE Prowess has been extensively used to access financial and ownership information for foreign owned MNE subsidiaries in India (Chari & Banalieva, 2015; Garg et al., 2022; for a recent review of papers using India as context refer to Mukherjee et al., 2022; Sewak & Sharma, 2020). Subsidiary Tenure was calculated as the logarithmic value of time since incorporation of the subsidiary and MNE Ownership as the percentage equity owned by the MNE.

In addition, we operationalised Subsidiary Performance as the ratio of profit after taxes and the net fixed assets. Subsidiary Size was measured as the logarithmic value of total sales measured in Indian Rupees million. We used CMIE Prowess to access this financial information for the subsidiaries We used Mergent Online to calculate MNE Size as the logarithmic value of total sales of the MNE measured in US$ millions. We used subsidiary performance, subsidiary size and MNE size as control variables in our analyses.

3.5 Analyses

Our data had MNE subsidiary financials and attributes measured over multiple years. This panel nature of our data necessitates that the statistical estimation of our data is either fixed effects or random effects. The choice between fixed effects and random effects was based on the results of a Hausman test. The Hausman test gave a Chi Squared value of 20.79 (p-value = 0.0041), thus indicating a preference for fixed effects estimation. A fixed effects estimation also accounts for unobserved and/ or unmeasured attributes that are time invariant (Hill et al., 2020). In our analyses we therefore use fixed effects analyses to test our hypotheses. We included fixed effects for the subsidiary, parent MNE and time. Through this, we were able to account for both observed and unobserved attributes specific to the subsidiary, MNE and period of analyses including but not limited to the industry in which the subsidiary operated. In addition, to alleviate challenges arising from heteroskedasticity, we used robust standard errors.

4 Results

In Table 1 we present the descriptive statistics and the corelation table. As expected, the Positive Externalities Investments and Positive CSR Intensity as well as the Negative Externalities Investments and Negative CSR Intensity have high correlations. But since we do not have them in the same regression model, the high correlations would not impact the analyses and its interpretation.

Incidentally, approximately 93% of the observations in the sample have Positive Externalities Investments coded as 1. This statistic, combined with the number of subsidiaries investing in socially relevant projects, indicates that all subsidiaries investing in socially relevant projects invest in projects relating to increasing positive externalities. The other 7% are the cases where the subsidiaries did not invest in social projects because they had non-profitable operations. From the descriptive statistics we see some support for our assertions in hypothesis 1.

Before estimating the analyses, in Table 2 we first considered the variance inflation factor (VIF) values. In Table 2 Model 1, the average VIF was 1.3 and maximum for any variable was 1.5. In Models 2 and 3, the average VIF was 1.2 and maximum for any variable was less than 1.4. Since all VIF values were well below 4, and the pair-wise correlations were low, we concluded that multi-collinearity was not a major concern in our analyses.

In Table 2 Model 1, we present the analyses with CSR Intensity as the dependent variable and we test hypothesis 1. In Model 1, we focus on the statistical significance level and sign for Positive Externalities Investments and Negative Externalities Investments. The slope estimate for Positive Externalities Investments is significant and positive (p-value = 0.066), while the slope estimate for Negative Externalities Investments is not statistically significant. This indicates empirical support for hypothesis 1.

In Table 2 Model 2, we present the analyses with Positive CSR Intensity as the dependent variable and test hypotheses 2a and 3a. We find the slope estimate for subsidiary age is not statistically significant, but the slope estimate for MNE ownership is significant and negative. That is, statistically older subsidiaries are not investing in SI projects that are associated with increasing positive externalities. However, higher MNE ownership of the subsidiary results in lower investments in SI projects that are associated with increasing positive externalities. This indicates statistical support for the assertions of hypothesis 3a but not hypothesis 2a.

In Table 2 Model 3, we present the analyses with Negative CSR Intensity as the dependent variable and test hypotheses 2b and 3b. We find the slope estimate for subsidiary age is statistically significant and positive, but the slope estimate for MNE ownership is not significant. That is, statistically older subsidiaries invest in SI projects that are associated with decreasing negative externalities. However, higher MNE ownership of the subsidiary does not statistically impact the investments associated with decreasing negative externalities. This indicates statistical support for the assertions in hypothesis 2b but not hypothesis 3b.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Our analyses support hypothesis 1 and so suggest that MNE subsidiaries in India tend to invest in projects which increase positive externalities rather than reduce negative externalities. Additionally, older subsidiaries tend to have greater investments in reducing negative externalities (hypothesis 2b) whilst subsidiaries with higher MNE parent ownership tend to invest less in increasing positive externalities (hypothesis 3a).

Our findings for hypotheses 2 and 3 are consistent with the subsidiary embeddedness literature. Older subsidiaries are expected to be more embedded in the host country and so engage more in socially relevant projects which could lead to SI. Subsidiaries with higher parent ownership tend to be more embedded in the MNE environment and are therefore less likely to engage locally. However, what is interesting in our sample is that subsidiary age is related to greater investments in reducing negative externalities whereas parent ownership is related to less investments in increasing positive externalities. This indicates that there is a choice being exercised by these subsidiaries possibly based on certain company (parent and/ or subsidiary) and host/ home country characteristics which warrants further investigation.

The fact that the choices apparently being made by the MNE subsidiaries seem to be influenced by factors requiring further investigation is not surprising. The context-dependent nature of SI is acknowledged by scholars in that it is heavily shaped by particular opportunities from historical circumstance, for example at a macro-level prevailing types of institution and industry, prevailing technologies and availability of capital (Mulgan, 2019). Similarly, the importance of the local context at the micro-level is apparent since it has been found that SI implementations in subsistence marketplaces often do not have the intended effect because they do not take the specifics of local communities into account (Venugopal & Viswanathan, 2019). These aspects suggest that it may be useful to view SI in terms of the institutional logics perspective - not only in terms of the environment in which SI is being attempted but also in the way it can be fruitfully brought to bear on the organisation attempting to implement SI. This approach could be useful not only in the interpretation of our current results but also for identifying pointers for future research.

Mutch (2021) describes organisations as bundles of practices given relatively enduring but distinctive form, not just economic in nature, in order to pursue the substances which motivate them. In this sense, commercial organisations including MNEs can be viewed as instantiations of the corporate logic, being normally organised for the pursuit of financial profit, with corresponding structures and mindsets. They would usually not pursue UNSDGs unless for ulterior motives which has been a common criticism of CSR – that companies espouse to it only for reputational purposes (Dionisio & de Vargas, 2020). However, CSR is being mandated in the unique context of India, which can be considered to be a change in the prevailing state logic. Consequently, MNE subsidiaries are in the unusual position of being forced to pursue unaccustomed ends, whilst the corporation logic of the MNE as a whole remains relatively unchanged. Our findings that this results in them being more involved in the increase of positive externalities (hypothesis 1) is consistent with the literature in that this seems to be favoured generally by MNEs, for example to build a stronger competitive advantage (Ali et al., 2018; Montiel et al., 2021) When the ties to the parent MNE are relatively stronger, there is less investment in the increase of positive externalities (hypothesis 3a). However, when the MNE subsidiary is more embedded in the local community, there is relatively more spend on the reduction of negative externalities (hypothesis 2b). Altogether, an argument can be made that commercial organisations are normally motivated by the corporation and market logics in a manner which is more consistent with the positive externalities of increasing wealth, knowledge and health. However, when these motivations are weakened by a greater degree of embeddedness in the local community, there is a relative increase in the recognition of the importance of reducing negative externalities – the reduction of the overuse of natural resources, harm to social cohesion and overconsumption. This indicates a change in values in the sense of what is being perceived as valuable and important. The MNE subsidiaries with higher MNE ownership see increasing wealth, knowledge and health as being relatively valuable and important, whereas the subsidiaries with greater local embeddedness place more value on reducing the harm caused by pollution, resource overuse and inequality. In terms of an institutional logic based view, the impact of the change in the state logic is dependent on the form of the corporation logic within the MNEs and their subsidiaries. The higher degree of local embeddedness can be seen as a relative weakening of the ties between parent and subsidiary, a weakening of the salience of the corporation and market logics and an increase in that of the community logic. This results in greater emphasis being placed on reducing the harm associated with negative externalities and the importance of organisations embracing this combination of market and community has been emphasised by other scholars as mentioned above (Venkataraman et al., 2016; Venugopal & Viswanathan, 2019).

5.1 Contributions and Implications

Our paper makes two theoretical contributions. Firstly, the above discussion demonstrates the value of applying the theoretical lens afforded by the institutional logics perspective to empirical results. By definition, SI is about the social and so a wider perspective is needed than that provided by other commonly used approaches such as the resource-based view. With its explicit focus on non-market logics such as that of the community, the institutional logics perspective provides a suitable way of examining SI, the demonstration of which in our paper is a significant theoretical contribution to the literature. A further contribution is to the SI literature on India. To date, no other scholars have undertaken an empirical evaluation of company reports to show the impact of the mandated Act on SI initiatives. Consequently, our paper can claim to provide this contribution.

Secondly, our results indicate that, as subsidiaries spend more time in emerging markets, they become more aware of the nuanced social-economic situation of the host country constituents. Consequently, the subsidiary then attempts to solve such issues through reducing negative externalities. In other words, consistent with embeddedness arguments, as the subsidiary becomes more locally embedded it may develop SI projects connected to the community logic and thus attempt to reduce negative externalities. In contrast, higher MNE embeddedness reduces the propensity to follow the community logic and increases adherence to the market logic of the MNE. We therefore contribute by connecting SI with embeddedness and the logics perspective, especially in the contexts of the market and community logics.

Our research also leads to the following practical and policy implications. MNE subsidiaries undertaking SI initiatives can be more conscious of the difference between the categories of UNSDGs, their associated positive and negative externalities and the factors which may be important in their choice of which to influence. If they are relatively new to the host country, the usual path is for them to seek to increase positive externalities whilst reducing negative externalities becomes more usual as subsidiaries become more embedded in local communities. Awareness of this trend may then inform their choice, for example by seeking differentiation and going against it. This could take the form of new entrants deliberately targeting the reduction of negative externalities in the form of implementing superior standards in comparison to domestic competitors. Such standards may be directed at reducing the overconsumption of natural resources (e.g. improving energy efficiency and increasing renewable energy use), reducing harm to social cohesion (e.g. widening access to employment and refraining from corruption) and reducing overconsumption (e.g. establishing product repair, reuse and recycling facilities and establishing local waste management facilities). This could lead to them being seen as being more innovative and responsible by host country governments and citizens, increasing sales and enabling the recruitment of better employees, especially younger, more educated ones who may be more concerned about the impact of companies on society. Policy implications include a similar awareness of this pattern for government bodies which may consequently attempt to influence it in line with their objectives by mandating which group of UNSDGs the MNE initiatives should seek to address. If most MNE subsidiaries are targeting positive externalities, incentives in the form of tax breaks could be given to companies working to decrease negative externalities in order to achieve a more balanced result overall.

5.2 Limitations and Future Research

Our study has the following limitations. First, we empirically examined the SI investments made by MNE subsidiaries in India but our results are based on data from large firms in the manufacturing sector. Therefore, future research on mid or small-sized firms, the service sector or comparing developed and developing countries may provide further insights. Second, we compared overall spend on positive and negative externalities by subsidiaries to tackle grand challenges. One potential direction for future research is to explore SI investments in different types of positive and negative externalities to bring a more nuanced understanding of the role played by foreign MNE subsidiaries. Third, our results show that ownership and subsidiary age underpin the SI investments. Future studies using qualitative data could provide insights into the reasoning behind the differences in positive versus negative externalities investment based on other key subsidiary characteristics. These could include such aspects as organisation structure and purpose, aimed at shedding light on institutional factors such as the corporation logic and the relative salience of market and community logics. In addition, future studies could include other variables in a model potentially associated with subsidiary embeddedness, such as industry type, market conditions and collaboration with local NGOs engaged in SI.

In conclusion, although we stress that our results should be viewed as more exploratory than conclusive, we contend that they do throw up some fascinating pointers as to future research possibilities. It is clear that the research context of India represents a unique situation, but it is not unreasonable to suggest that the results may also have a more general applicability. Our findings suggest that whilst MNEs can play an important role in SI, they may be influenced by a number of factors in their choice of the type of SI they aim to promote. These seem to include the degree of local embeddedness and ownership of the parent MNE although clearly there are others which will be important. Whilst the institutional logics perspective may suggest that this can be interpreted in terms of the relative influence of the corporate, market and community logics, further research is needed before this can be firmly asserted.

References

Ajwani-Ramchandani, R., Figueira, S., Torres de Oliveira, R., Jha, S., Ramchandani, A., & Schuricht, L. (2021). Towards a circular economy for packaging waste by using new technologies: The case of large multinationals in emerging economies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 125139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125139

Ali, S., Hussain, T., Zhang, G., Nurunnabi, M., & Li, B. (2018). The Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals in BRICS Countries. Sustainability, 10(7), 2513. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/7/2513.

Almeida, P., & Phene, A. (2004). Subsidiaries and knowledge creation: The influence of the MNC and host country on innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 25(8–9), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.388.

Almodóvar, P., & Nguyen, Q. T. K. (2022). Product innovation of domestic firms versus foreign MNE subsidiaries: The role of external knowledge sources. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 184, 122000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122000.

Altuna, N., Contri, A. M., Dell’Era, C., Frattini, F., & Maccarrone, P. (2015). Managing social innovation in for-profit organizations: The case of Intesa Sanpaolo. European Journal of Innovation Management, 18(2), 258–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-06-2014-0058.

Alvesson, M., & Spicer, A. (2019). Neo-institutional theory and organization studies: A mid-life crisis? Organization Studies, 40(2), 199–218.

Andersson, U., & Forsgren, M. (1996). Subsidiary embeddedness and control in the multinational corporation. International Business Review, 5(5), 487–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/0969-5931(96)00023-6.

Andersson, U., & Forsgren, M. (2000). In search of Centre of Excellence: Network Embeddedness and Subsidiary roles in multinational corporations. MIR: Management International Review, 40(4), 329–350. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40836151.

Andersson, U., Forsgren, M., & Holm, U. (2002). The strategic impact of external networks: Subsidiary performance and competence development in the multinational corporation. Strategic Management Journal, 23(11), 979–996. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.267.

Andersson, U., Björkman, I., & Forsgren, M. (2005). Managing subsidiary knowledge creation: The effect of control mechanisms on subsidiary local embeddedness. International Business Review, 14(5), 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2005.07.001.

Attah-Boakye, R., Adams, K., Yu, H., & Koukpaki, A. S. F. (2022). Eco-environmental footprint and value chains of technology multinational enterprises operating in emerging economies. Strategic Change, 31(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2479.

Balon, V., Kottala, S. Y., & Reddy, K. S. (2022). Mandatory corporate social responsibility and firm performance in emerging economies: An institution-based view. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stae.2022.100023.

Bansal, S., Khanna, M., & Sydlowski, J. (2021). Incentives for corporate social responsibility in India: Mandate, peer pressure and crowding-out effects. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 105, 102382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2020.102382.

Barbaglia, M., Bianchini, R., Butticè, V., Elia, S., & Mariani, M. M. (2023). The role of environmental sustainability in the relocation choices of MNEs: Back to the home country or welcome in a new host country? Journal of International Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2023.101059.

Bell, R. G., Filatotchev, I., & Rasheed, A. A. (2012). The liability of foreignness in capital markets: Sources and remedies. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.55.

Beloskar, V. D., & Rao, S. V. D. N. (2022). Corporate social responsibility: Is too much bad?—Evidence from India. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 29(2), 221–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10690-021-09347-3.

Benito, G. R., & Gripsrud, G. (1992). The expansion of foreign direct investments: Discrete rational location choices or a cultural learning process? Journal of International Business Studies, 23, 461–476.

Birkinshaw, J., & Hood, N. (1998). Multinational Subsidiary Evolution: Capability and Charter Change in Foreign-owned Subsidiary companies. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 773–795. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.1255638.

Bu, M., Xu, L., & Tang, R. W. (2023). MNEs’ transfer of socially irresponsible practices: A replication with new extensions. Journal of World Business, 58(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101384.

Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. (2017). Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9), 1045–1064. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0102-z.

Buckley, P. J., Cui, L., Chen, L., Li, Y., & Choi, Y. (2023). Following their predecessors’ journey? A review of EMNE studies and avenues for interdisciplinary inquiry. Journal of World Business, 58(2), 101422.

Cannavale, C., Claudio, L., & Simoni, M. (2021). How social innovations spread globally through the process of reverse innovation: A case-study from the South Korea. Italian Journal of Marketing, 2021(4), 421–440.

Chari, M. D., & Banalieva, E. R. (2015). How do pro-market reforms impact firm profitability? The case of India under reform. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 357–367.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 128–152.

Crilly, D. (2011). Predicting stakeholder orientation in the multinational enterprise: A mid-range theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 694–717. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.57.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Doh, J. P., Giuliani, E., Montiel, I., & Park, J. (2022). The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals: Pros and Cons for Managers of Multinationals. AIB Insights, 22(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.46697/001c.32530.

de Visser-Amundson, A. (2022). A multi-stakeholder partnership to fight food waste in the hospitality industry: A contribution to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 12 and 17. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(10), 2448–2475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1849232.

Díaz-Perdomo, Y., Álvarez-González, L. I., & Sanzo-Pérez, M. J. (2021). A way to boost the impact of business on 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Co-creation with non-profits for Social Innovation [Hypothesis and theory]. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719907.

Dionisio, M., & de Vargas, E. R. (2020). Corporate social innovation: A systematic literature review. International Business Review, 29(2), 101641.

Du, J., & Williams, C. (2017). Innovative projects between MNE subsidiaries and local partners in China: Exploring locations and inter-organizational trust. Journal of International Management, 23(1), 16–31.

Dunning, J. H., & Fortanier, F. (2007). Multinational Enterprises and the New Development paradigm: Consequences for host Country Development. Multinational Business Review, 15(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/1525383X200700002.

Eang, M., Clarke, A., & Ordonez-Ponce, E. (2023). The roles of multinational enterprises in implementing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals at the local level. Business Research Quarterly, 26(1), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/23409444221140912.

Edwards-Schachter, M. E., Matti, C. E., & Alcántara, E. (2012). Fostering quality of life through social innovation: A living lab methodology study case. Review of Policy Research, 29(6), 672–692.

Eichler, G. M., & Schwarz, E. J. (2019). What sustainable development goals do Social innovations address? A Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Social Innovation Literature. Sustainability, 11(2), 522. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/2/522.

Elg, U., & Hånell, S. M. (2023). Driving sustainability in emerging markets: The leading role of multinationals. Industrial Marketing Management, 114, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.08.010.

Erin Bass, A., & Grøgaard, B. (2021). The long-term energy transition: Drivers, outcomes, and the role of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(5), 807–823. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00432-3.

European Commission (2011). A Renewed EU Strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility European Commission. Retrieved July 28 from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0681andfrom=ES.

Ferrón Vílchez, V., Carrasco, O., P., & Serrano Bernardo, F. A. (2022). SDGwashing: A critical view of the pursuit of SDGs and its relationship with environmental performance. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65(6), 1001–1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2022.2033960.

Foroudi, P., Akarsu, T. N., Marvi, R., & Balakrishnan, J. (2021). Intellectual evolution of social innovation: A bibliometric analysis and avenues for future research trends. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 446–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.03.026.

Foroudi, P., Marvi, R., Cuomo, M. T., Bagozzi, R., Dennis, C., & Jannelli, R. (2022). Consumer perceptions of Sustainable Development Goals: Conceptualization, Measurement and Contingent effects. British Journal of Management, 34(3), 1157–1183. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12637.

Foss, N. J., & Pedersen, T. (2002). Transferring knowledge in MNCs: The role of sources of subsidiary knowledge and organizational context. Journal of International Management, 8(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(01)00054-0.

Friedland, R. (2013). The gods of institutional life: Weber’s value spheres and the practice of polytheism. Critical Research on Religion, 1(1), 15–24.

Garg, G., Sewak, M., & Sharma, A. (2022). Learning from older siblings: Impact on subsidiary performance. International Business Review, 31(3), 101957.

Garnier, G. H. (1982). Context and decision making autonomy in the Foreign Affiliates of U.S. multinational corporations. Academy of Management Journal, 25(4), 893–908. https://doi.org/10.5465/256105.

Gehringer, T. (2020). Corporate foundations as Partnership brokers in supporting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability, 12(18), 7820. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/18/7820.

George, G., Howard-Grenville, J., Joshi, A., & Tihanyi, L. (2016). Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 1880–1895.

Ghauri, P. N., & Cooke, F. L. (2022). MNEs and United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The New frontiers of International Business: Development, evolving topics, and implications for practice (pp. 329–344). Springer.

Ghauri, P. N., & Wang, F. (2017). The Impact of Multinational Enterprises on Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction: Research Framework. In International Business & Management (Vol. 33, pp. 13–39). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1876-066X20170000033002.

Giuliani, E., & Macchi, C. (2013). Multinational corporations’ economic and human rights impacts on developing countries: A review and research agenda. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(2), 479–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bet060.

Govindarajan, V., & Ramamurti, R. (2011). Reverse innovation, emerging markets, and global strategy. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3-4), 191–205.

Greenwood, R., Díaz, A., Li, S., & Lorente, J. (2010). The multiplicity of institutional logics and the heterogeneity of organizational responses. Organization Science, 21(2), 521–539.

Gulati, R., Nohria, N., & Zaheer, A. (2000). Strategic networks. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:3<203::AID-SMJ102>3.0.CO;2-K.

Gümüsay, A. A., Claus, L., & Amis, J. (2020). Engaging with grand challenges: An institutional logics perspective. Organization Theory, 1(3), 2631787720960487.

Hanoteau, J. (2023). Do foreign MNEs alleviate multidimensional poverty in developing countries? Eurasian Business Review, 13(4), 719–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-023-00246-3.

Haritas, I., & Das, A. (2023). Simple doable goals: A roadmap for multinationals to help achieve the UN’s sustainable development goals. Society and Business Review, 18(4), 618–645. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-06-2022-0167.

Hatipoglu, B., Ertuna, B., & Salman, D. (2019). Corporate social responsibility in tourism as a tool for sustainable development. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2358–2375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0448.

Herrera, M. E. B. (2015). Creating competitive advantage by institutionalizing corporate social innovation. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1468–1474.

Hill, T. D., Davis, A. P., Roos, J. M., & French, M. T. (2020). Limitations of fixed-effects models for panel data. Sociological Perspectives, 63(3), 357–369.

Immelt, J. R., Govindarajan, V., & Trimble, C. (2009). How GE is disrupting itself. Harvard Business Review, 87(10), 56–65.

Isaac, V. R., Borini, F. M., Raziq, M. M., & Benito, G. R. G. (2019). From local to global innovation: The role of subsidiaries’ external relational embeddedness in an emerging market. International Business Review, 28(4), 638–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.12.009.

Jackson, T. (2014). Employment in Chinese MNEs: Appraising the Dragon’s gift to Sub-saharan Africa. Human Resource Management, 53(6), 897–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21565.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The internationalization process of the Firm—A model of Knowledge Development and increasing Foreign Market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490676.

Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016). The sustainable development goals and business. International Journal of Sales Retailing and Marketing, 5(2), 38–48.

Kanter, R. M. (1999). From spare change to real change: The social sector as beta site for business innovation. Harvard Business Review, 77(3), 122–123.

Keig, D. L., Brouthers, L. E., & Marshall, V. B. (2015). Formal and Informal Corruption environments and multinational enterprise Social Irresponsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 52(1), 89–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12102.

Kolk, A., & Pinkse, J. (2008). A perspective on multinational enterprises and climate change: Learning from an inconvenient truth? Journal of International Business Studies, 39(8), 1359–1378. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.61.

Kolk, A., Kourula, A., & Pisani, N. (2017). Multinational enterprises and the sustainable development goals: What do we know and how to proceed? Transnational Corporations, 24(3), 9–32.

Kostova, T., Beugelsdijk, S., Scott, W. R., Kunst, V. E., Chua, C. H., & van Essen, M. (2020). The construct of institutional distance through the lens of different institutional perspectives: Review, analysis, and recommendations. Journal of International Business Studies, 51, 467–497.

Kraatz, M., Flores, R., & Chandler, D. (2020). The value of values for institutional analysis. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 474–512.

Lane, P. J., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19(5), 461–477.

Lee, R. P., Spanjol, J., & Sun, S. L. (2019). Social Innovation in an interconnected world: Introduction to the Special Issue. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(6), 662–670.

Lim, C., Han, S., & Ito, H. (2013). Capability building through innovation for unserved lower end mega markets. Technovation, 33(12), 391–404.

Lind, C. H., Kang, O., Ljung, A., & Forsgren, M. (2018). MNC involvement in social innovations: The issue of knowledge, networks and power. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 16(1), 79–99.

Liou, R. S., & Rao-Nicholson, R. (2021). Multinational enterprises and sustainable development goals: A foreign subsidiary perspective on tackling wicked problems. Journal of International Business Policy, 4, 136–151.

Liu, W., & Heugens, P. P. M. A. R. (2023). Cross-sector collaborations in global supply chains as an opportunity structure: How NGOs promote corporate sustainability in China. Journal of International Business Studies. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00644-9.

London, T., & Hart, S. L. (2004). Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 350–370.

Luo, Y., & Peng, M. W. (1999). Learning to Compete in a transition economy: Experience, Environment, and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2), 269–295. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490070.

McGowan, K., & Westley, F. (2015). At the root of change: The history of social innovation. New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research, 52–68.

Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. (2016). Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 47, 3–22.

Molloy, C., Bankins, S., Kriz, A., & Barnes, L. (2020). Making sense of an interconnected world: How innovation champions drive social innovation in the not-for‐profit context. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 37(4), 274–296.