Abstract

International business scholars have long recognized the potential influence of cultural differences on foreign divestment; however, the empirical results are mixed. Our study helps resolve this contradiction and contribute to the existing literature in three ways. First, we advocate the use of cultural friction metric, instead of the more traditional cultural distance approach. This overcomes a key limitation in the modelling the impact of cultural differences. The friction construct metric includes an index of firm-specific factors, referred to as the degree of ‘cultural interaction’. This index moderates the impact of cultural distance, reflecting firm—level differences. We also build on calls for more Positive Organizational Scholarship by challenging the negative bias in the international business literature and propose a curvilinear effect of cultural differences on divestment probability. Lastly, we investigate a potential boundary condition—the moderating effect of entry mode on the main hypothesis. Our empirical sample include 2120 Finnish foreign subsidiaries operating in 40 countries during 1970–2010. Our analyses confirm that the cultural differences, when measured by the friction metric, appear to be a significant and superior predictor of subsidiary divestment probability, and that the relationship appears to be U-shaped. Our robustness analyses also highlight the importance of which cultural framework is applied and controlling for selection bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Foreign direct investments (FDIs) have an important strategic role in multinational enterprises (MNEs). However, a significant number of these investments are subsequently divested (UNCTAD, 2021). As such, foreign divestment—referring to “the deliberate and voluntary liquidation or sale of all or a major part of an active operation” (Boddewyn, 1979)—is a sensitive decision because it has implications on MNEs’ growth and performance, their international portfolio, and shareholders’ value (Song & Lee, 2017; Tan & Sousa, 2019). As a result, this burgeoning literature has received remarkable attention from academic researchers (Peng & Beamish, 2019; Schmid & Morschett, 2020).

Within this stream of literature, numerous scholars have recognized the potential importance of cultural distance, or cultural differences,Footnote 1 between home and host countries to the divestment debate (Beugelsdijk & Welzel, 2018; Kang et al., 2017; Popli et al., 2016). However, the studies on foreign divestment and cultural differences (Meschi et al., 2016; Park & Chung, 2019; Wang & Larimo, 2020) have yielded mixed results: variously reporting positive, negative, and non-significant relationships. As such, our understanding of how cultural differences affect foreign divestment appears to be incomplete.

We argue that three key issues may explain the ambiguous findings in previous studies. First, numerous scholars (Konara & Mohr, 2019; Li et al., 2019; Popli et al., 2016; Shenkar, 2001; Singh et al., 2019) have criticized the use of the 'national cultural distance' metric—a quantitative score computed to measure differences between national cultures (Kogut & Singh, 1988). One aspect of these criticisms is that cultural distance only reflects differences at the national level (e.g., Shenkar, 2001), and does not reflect how individual firms may perceive and respond to cultural differences differently.

Second, scholars in the past may have overemphasized the negative effect of cultural differences in IB literature (Edman, 2016; Reus & Lamont, 2009; Stahl & Tung, 2015). Stahl and Tung (2015) have systematically reviewed the literature on cultural differences and assert that cultural differences do not always harm the outcomes of MNEs. Indeed, Singh et al. (2019) confirm that under certain conditions, cultural differences may yield positive outcomes. However, nonlinear modelling of cultural differences, allowing for both positive and negative effects, has not been included in previous foreign divestment studies.

Third, several studies on cultural differences have emphasized that contingency effects may influence the impact of cultural differences. The moderating role of entry mode is one such boundary condition (Beugelsdijk et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2015; Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Shenkar et al., 2008). However, empirical studies, in general, have neglected the role that entry mode choice may play in subsidiary survival (Mudambi & Zahra, 2007; Shaver, 1998); and amongst the few that have explored this moderating effect, the findings appear to be inconsistent.

By addressing these three concerns, our research aims to improve the understanding of the impact of cultural differences on foreign divestment, and thus, constituting foreign divestment literature in three ways. First, we build on the nascent work of Shenkar and his colleagues (e.g., Li et al., 2019; Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Shenkar, 2001, 2012), who first proposed the concept of cultural friction, and argue that it is superior to cultural distance when modelling the impact of cultural differences. We do so by applying their index of cultural friction as an alternative approach for modeling the impact of cultural differences. In keeping with the cultural distance approach, Luo and Shenkar (2011) define a key element of cultural friction as the separation between two national cultures. However, they depart from the cultural distance approach by arguing that this ‘separation’ will be moderated the degree of interaction between two entities (i.e., the MNE and the foreign market). As a result, they argue that cultural friction is context-specific. It includes not only the cultural distance, but also firm-level factors which may interact with the cross-cultural context. They refer to this latter group of factors as the degree of cultural interaction. We contend that this may be critical because the degree to which cultural differences influence foreign firms may depend on how the firms perceive and respond to the different contexts. Accordingly, the understanding of the impact of cultural differences could be explained more comprehensively by using the friction construct, instead of the traditional “national cultural distance” metric.

It is worth mentioning here that, while the cultural friction construct has received increasing attention, the application of it to empirically examine its impact has been extremely limited. Only a few previous studies have empirical tested the cultural friction metric (i.e., Koch et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2019); and, while in general, they have confirmed its statistical significance, none of them actually test the impact of cultural friction in direct comparison to the metric that it is purported to replace (i.e., cultural distance). In this regard, our paper makes a unique contribution because it not only tests the efficacy of Luo and Shenkar’s (2011) cultural friction index, but also directly compares that efficacy with the more traditional measure of cultural distance. By unbundling the main elements of the friction metric—i.e., the cultural distance and the degree of cultural interaction, we are able to compare the relative contributions of the two main components. Thus, in applying cultural friction to examine the influence of cultural differences, our study provides unique empirical evidence not only of the reliability, accuracy, and validity of the friction concept proposed by Shenkar (2001), but also its superiority over existing approaches.

In our second major contribution, we follow the recommendations of Stahl and Tung (2015) and embrace the Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS) perspective. This allows us to shed light on the nature of the role that cultural differences play in foreign divestment. Specifically, we question and test the “assumption of linearity" and the implicit belief that cultural differences always yield a negative impact on foreign firms. We theorize and propose that under some circumstances foreign firms may be able to capitalize on several benefits of operating in a different culture; thus, decreasing the likelihood of divestment. At low levels of cultural differences, these benefits may be quite substantial, and the foreign firms may be able to mitigate the negative effects of operating in a different culture. However, this effect is not unbounded, and eventually, a turning point is reached where the negative effects dominate the relationship. As such, local exploitation and exploration may no longer be effective; thus, increasing the likelihood of divestment.

Our third contribution concerns the moderating effect of entry mode choice on the impact of cultural friction on divestment. While prior international business scholars (e.g., Brouthers, 2013; Slangen & Hennart, 2008a; Zhao et al., 2017) have defined entry modes in a variety of different forms—e.g., wholly owned subsidiaries versus joint ventures, and greenfield investments versus acquisitions, Luo and Shenkar’s (2011) refer to entry mode choices as the latter (i.e., greenfield versus acquisition) when they developed the cultural friction construct. As a result, we follow the Luo and Shenkar’s (2011) definition as one of our main aims is to examine the validity of their construct—cultural friction. Thus, we examine the moderating role of entry mode in reshaping the influence of cultural differences on foreign divestment, arguing that entry mode has a differentiated impact on the costs and benefits that firms have paid or achieved in cross-cultural contexts (Malhotra et al., 2011; Slangen & Hennart, 2008a). We propose that entry mode may be a “distance closing mechanism” that moderates cultural differences–foreign divestment relationship.

2 Theory and Hypothesis Development

In order to develop our two main hypotheses, we first need to establish working definitions of the key constructs. The first of these concerns the related concepts of culture and cultural differences. The second section concerns the concept of cultural friction, and in particular how it differs from the more widely acknowledged concept of cultural distance. This section also delves into the reasons why cultural friction may be a more comprehensive and superior approach for modeling cultural differences. We then develop the first hypothesis concerning the curvilinear relationship between cultural friction and foreign divestment; and finally, we develop the second hypothesis concerning the moderating impact of entry mode.

2.1 The Concepts of Culture and Cultural Differences

The concepts of cultural and cultural differences, particularly using the metaphor of cultural distance, have been widely embraced in the IB literature (Konara & Mohr, 2019; Tung & Verbeke, 2010; Zaheer et al., 2012). In the words of the pre-eminent author in this field, Hofstede (1980, p 25) defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another.” Following a similar theme, though using slightly different terminology, and expanding on the number of underlying dimensions, Schwartz (1999) describes culture a set of values that are common across a society or cultural group. And more recently, the GLOBE project (House et al., 2004) explicitly builds on the earlier work of Hofstede, but again expands on the number of underlying dimensions, and proposes that each could be measured in terms practices and/or values. Nevertheless, while there remains open debate about the number of underlying cultural dimensions, and which of the three main cultural frameworks (i.e., Hofstede, Schwartz, or GLOBE) is the most appropriate approach for measuring of those dimensions, we believe it is fair to argue that the concept of culture as ‘a set of beliefs, values, and practices that are shared across a group of individuals’ is broadly accepted in the IB literature.

With respect to the concept of cultural differences, this simply refers to the differences between the dominant culture of one country and another. The main point of contention here is purely a methodological one—what approach is most appropriate to combine multiple dimensions into a single index? Historically, the Kogut and Singh (1988) approach—a variation Euclidean distance—is the most commonly used approach; however, Berry et al.’s (2010) Mahalanobis distance approach has gradually attracted more attention.

We should note here that while our hypotheses inherently concern culture and cultural differences, they are not contingent on any particular cultural framework, nor the metric for combining their dimensions into an index. As a result, while in the results section of this paper we initially report our results concerning the GLOBE Values framework for simplicity, we repeat all of the empirical tests for each of the main cultural frameworks.

2.2 Cultural Friction Versus Cultural Distance

As noted earlier, previous cross-cultural studies have tended to use the cultural distance approach (Kogut & Singh, 1988) to model the impact of cultural differences. Indeed, in our review of the existing cultural difference—foreign subsidiary divestment literature confirms this (see Table 1). In a review of 27 studies between 1996 and 2020 that have tested the relationship between cultural differences and foreign subsidiary divestment, all of the studies included a Hofstede-based form of cultural distance, either as the main independent variable or as a control variable. However, in parallel to this, numerous critics have argued that both the concept and operationalization of cultural distance have several weaknesses, such as illusions of symmetry, stability, linearity, causality, and discordance; and assumptions of corporate homogeneity and equivalence (see Drogendijk & Zander, 2010; Popli et al., 2016; Shenkar, 2001; Shenkar et al., 2008 for more details). Indeed, Shenkar (2001, p. 520) argues that “the appeal of the cultural distance construct is, unfortunately, illusory.” It is worth noting that, several exercises have been performed to overcome the aforementioned illusions of cultural distance. For instance, scholars have examined the moderating effect of various factors on cultural distance–firms’ internationalization relationship (Brouthers & Brouthers, 2001; Kang et al., 2017; Malhotra et al., 2011; Peng & Beamish, 2014; Wang & Schaan, 2008). Their findings point out the crucial role of focusing on firms’ specific conditions in measuring the cultural effect. Similarly, Popli et al. (2016) conceptualize the 'cultural experience reserve' to highlight the importance of contextual variation in conceptualizing the cultural differences.

It is in this same seminal article that Shenkar (2001) first suggested the friction metaphor as a superior approach. A subsequent article (Luo & Shenkar, 2011) then provided a more detailed conceptualization and methodology to understand and measure construct. In his words, Shenkar argues that cultural friction refers to both the scale and essence of the interface between interacting cultures (i.e., home and host cultures), and the interface when an operating business must straddle multiple cultures (Shenkar, 2001, p. 528). Simply stated, cultural friction more accurately reflects the overall impact that a different cultural context may have on a specific foreign firm, in contrast to the cultural distance approach which merely reflects national-level averages of cultural differences. Accordingly, cultural friction includes both the differences in national cultures and a range of firms’ specific factors accessing the actual interaction with the nationally cultural distance (Luo & Shenkar, 2011). In doing so, cultural friction reflects both the cultural distance (national level) and the degree of cultural interaction (firm level) (Koch et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2019). Cultural interaction refers to the level of interface between the foreign firm and the host cultural context. In essence, how intensely does the MNE, through its foreign subsidiaries, need to interact with the local culture. As such, the impact of cultural differences on MNE’s internationalization should be defined based on the combination between national cultural distance and firm level of cultural interaction. For example, when low levels of cultural distance are combined with low levels of cultural interaction, this will generate very low levels of cultural friction. In contrast, very high levels of cultural friction are created by the combination of high levels of cultural distance and high levels of cultural interaction. However, of more practical relevance to managers are scenarios such as where MNEs can respond to higher levels of cultural distance by entering such markets with lower levels of cultural interaction, allowing the firm to maintain more manageable levels of overall cultural friction, while still exploiting distant opportunities. Conversely, much higher levels of cultural interaction can be tolerated when lower levels of cultural distance are present, enabling the firm to exploit opportunities more rapidly and effectively.

In brief summary, the cultural friction approach has two particular advantages over the cultural distance approach. First, previous research has confirmed that the impact of cultural differences may vary depending on how firms involve the different contexts; and thus, the influence of cultural differences is probably not equal for all firms in a given pair of home–host countries (Singh et al., 2019; Slangen & Hennart, 2008b). Nevertheless, cultural distance is computed exclusively at the national level; and thus, is the same for all investments originating from the same pairs of home–host countries. In contrast, cultural friction is able to reflect contextual variations, and considers the nature of the subsidiary and its parent firm (Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Popli et al., 2016). Thus, cultural friction reflects both the scale and nature of the interaction between entities.

Second, cultural friction also allows for the fact that firms may respond differently to the same cultural differences at different stages in their internationalization (Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Popli et al., 2016; Shenkar, 2012). Cultural friction reflects why early entrants may suffer the differences more severely than later entrants, which may take advantage of the legitimacy spillover (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). Because of the aforementioned arguments, we contend that it is more appropriate and accurate to evaluate the effect of cultural differences using the more comprehensive friction-based approach, than by the simple distance-based approach.

Interestingly, although Shenkar’s numerous calls for fellow researchers to switch to the cultural friction approach (Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Shenkar, 2012; Shenkar et al., 2008, 2022) have received many citations,Footnote 2 the proposed index (Luo & Shenkar, 2011) has only attracted modest empirical application. Thus far, very few studies in the IB field have empirically tested the concept of cultural friction: Koch et al. (2016) has explored how individual leadership dimensions of cultural friction influence subsidiary survival; Singh et al. (2019) test the relationship between cultural friction and subsidiary performance; Joshi and Lahiri (2015) examine the impact of language friction on international alliance formation, and Popli et al. (2016) have explored the impact of cultural friction on deal abandonment. However, while they all endorse the concept of friction, none of these four studies actually employ and test the cultural friction index as proposed by Luo and Shenkar (2011). Indeed, to our knowledge, Li et al. (2019) is the only study to date that empirically tests the Luo and Shenkar index. They find it a statistically significant predictor of export performance. Unfortunately, they do not provide any comparison with a more traditional cultural distance metric. As a result, we argue that the most salient aspect of the cultural friction construct—i.e., being a superior approach to model cultural differences—remains untested in any setting. Therefore, we add to the literature by not only testing cultural friction in a novel context, but by also testing whether it is truly a superior approach for modeling cultural differences.

2.3 The Curvilinear Linear Impact of Cultural Friction on Foreign Divestment

As mentioned in the introduction, the POS perspective (e.g., Stahl et al., 2016, 2017; Stahl & Tung, 2015; Tung & Stahl, 2018) played a major role in motivating our hypothesis concerning the impact of cultural friction on foreign divestment. In this stream of literature, Stahl and his colleagues have urged IB researchers to not only delve into the disadvantages of cultural differences (e.g., miscommunication, lack of trust, agency problems, transaction costs), but also into the advantages (e.g., learning, combinatory, synergistic benefits, diversity, arbitrage, and innovation). Specifically, Stahl et al. (2016) encourage future cultural studies to challenge the traditional biases concerning cultural differences (i.e., the assumption that they always yield negative outcomes).

Nevertheless, the POS lens is not a single theory per se, rather it represents a different view for considering a given phenomenon (Cameron, 2017; Caza & Caza, 2008; Stahl et al., 2016). The familiarity of a given phenomenon often biases our perceptions and “we tend to understand the world in ways that conform to [the] means available to us” (Caza & Caza, 2008, p. 21). Thus, the most important contribution of the POS perspective is not for pointing out surprising results, nor for proposing a new construct, but for challenging “the deficit model that shapes the design and conduct of organizational research”. As a result, numerous scholars advocate the use of this theoretical view to challenge the negative bias among previous cultural studies (Edman, 2016; Stahl & Tung, 2015), and highlight the potential benefits of cultural differences, in addition to the already heavily explored negative effects (Cameron, 2017; Stahl et al., 2016).

It is worth mentioning here that while the POS lens encourages a more balanced treatment of both positive and negative outcomes of the differences, one still needs to draw upon on specific theoretical mechanisms in order to develop a comprehensive proposal (Cameron, 2017; Edman, 2016). Thus, in the following sections, in order to develop our arguments concerning the curvilinear impact of cultural friction on foreign divestment, we will first focus on the synergistic benefits of cultural differences as espoused by Stahl et al. 2016, 2017). This perspective draws upon the resource-based view (Barney, 1991) and the organizational learning theory (Levinthal & March, 1993). We will then develop our arguments concerning the disadvantages of cultural differences by drawing upon institutional theory and the transaction cost perspective. We then bring these two perspectives together to make predictions concerning their net impact on foreign divestment.

2.3.1 The Potential Benefits of Cultural Friction

As already acknowledged, there has been minimal effort expended on developing theoretical explanations for the benefits of the cultural differences (Stahl et al., 2017), but a few alternative approaches have been flagged by various authors. In their special call, Stahl et al. (2017) propose that benefits of being culturally different could be explained based on the synergistic benefits that are rooted from the knowledge/resource-based view (Barney, 1991) and the organizational learning theory (Levinthal & March, 1993). In essence, the knowledge/resource-based view explains firm’s ability to acquire, transfer and utilize knowledge or resources from surrounding environments, e.g., host cultural environment, that later enhance firm performance and its survival. Organizational learning theory delves into the experience aspects that firms utilize to make organizational decisions and strategies. These two theories have been applied in previous foreign divestment studies (Delios & Beamish, 2001; Kim et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011). Adopting the two theories, previous studies explained that MNEs acquire, utilize, and transfer knowledge from previous transactions and interaction with the culturally different environment. In doing so, the MNEs enhance their ability to cope with liabilities of foreignness while enjoying local exploration and exploitation opportunities.

Prior scholars also explain the benefits of cultural differences based on the diversity literature (Cox & Blake, 1991; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). Elaborating on the information-processing theory, researchers report that cultural diversity brings different contributions to teams, e.g., broader territory of information, broader range of networks and perspective; and thus, enhancing problem-solving, creativity, innovation, system flexibility, and adaptability (Cox & Blake, 1991; Stahl et al., 2010; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). For instance, Cox and Blake (1991) state that cultural differences promote knowledge transfers, and that diversity brings net-added value to organization processes. Theorizing from the information/decision-making perspective, van Knippenberg and Schippers (2007) similarly explain that diversity brings broader knowledge, perspective and enhances work group quality, creative and innovation. Stahl et al. (2017) further propose that diversity yields benefits with respect to exploration via global activities, e.g., search, variation, experimentation, and discovery.

Diversity also provides positive agglomeration effects, e.g., to access different knowledge or resources embedded in foreign countries and relatively efficient diffusion among them, to generate more alternatives which are good for decision making process, and increase levels of flexibility (Arregle et al., 2009; Regnér & Edman, 2014). For instance, prior scholars show that MNEs and their subsidiaries can enhance the firm’s global competences by accessing a wider variety of knowledge and sources of learning, optimizing the value chain, and upgrading firms’ existing knowledge stock (Morosini et al., 1998; Nachum, 2010; Nachum et al., 2008; Zaheer et al., 2012). This can apply to different aspects of foreign performance: e.g., innovation, knowledge stock, customer preferences or other potential arbitrage opportunities, researchers reported positive outcomes of cultural differences (e.g., Edman, 2016; Stahl et al., 2016).

Other researchers (Gaur & Lu, 2007; Gomez-Mejia & Palich, 1997) have also framed the benefits of cultural differences in terms of arbitrage logics. Basically, arbitrage logic explains that MNEs operate in foreign countries to exploit differences between countries to optimize their organizational strategies in international markets; and thus, benefiting from these differences (Arregle et al., 2009, 2016; Regnér & Edman, 2014). For instance, Gaur and Lu (2007) confirmed that the exploration of location-specific advantages and exploration of firm-specific resources encourage firm’s internationalization. In this regard, operating in culturally distant context, MNEs and their subsidiaries may acquire certain benefits, e.g., providing a potential source of important value, learning opportunities, and networks (Arregle et al., 2016; Beugelsdijk et al., 2018; Regnér & Edman, 2014; Wang & Schaan, 2008). Hence, the arbitrage logic encourages MNEs to operate in culturally distant countries: however, the scope of arbitrage becomes narrower, the marginal benefits decline as the distance increases (Arregle et al., 2009, 2016; Gaur & Lu, 2007; Regnér & Edman, 2014).

As a result, we predict that when cultural differences reach very high levels, foreign firms may not always be able to capitalize on these advantages. In addition to the initial costs paid for setting up international operations, as the cultural differences increase, foreign subsidiaries must pay extra costs and take additional risks if they want to exploit and explore the related local resources and knowledge. For instance, Gaur and Lu (2007) confirm that operating in distant countries could provide opportunities for institutional arbitrage, but the scope of such arbitrage becomes narrower at high levels of differences. We also propose that firms can more easily integrate and upgrade their existing knowledge if the new knowledge is reasonably similar; but as the differences increase, conflicts are more likely to be triggered, and knowledge transfer becomes inefficient. Prior scholars confirm that knowledge transfer will only occur with reasonable costs if there is a relative proximity among countries (Arregle et al., 2009, 2016). Beugelsdijk et al. (2017) further assert that firms will probably incur more costs and time on travel, as well as have more communication and coordination challenges when doing business in foreign markets with greater differences from their homeland. Additionally, greater cultural differences may hamper trust development and communication between partners (Bjo et al., 2007). Hence, we propose that when operating at low levels of cultural differences, MNEs and their foreign subsidiaries may gain some advantages, but these benefits may only increase at a diminishing rate when the differences increase because the firm's ability to capture the cross-national benefits decreases.

2.3.2 The Disadvantages of Cultural Friction

In contrast to the preceding discussion, the potential direct negative effects of cultural differences on a firms’ internationalization—whether they are modeled as cultural distance or cultural friction—have been long acknowledged and discussed in the IB literature (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Kostova et al., 2008). However, scholars have employed a variety of theoretical perspectives in order to explain how and why these negative effects influence the survival of a foreign subsidiary. For instance, with respect to the institutional perspective, cultural differences are typically viewed as a form of informal institutional distance (e.g., Meyer et al., 2009) and/or cognitive distance (e.g., Gaur & Lu, 2007). This perspective provides a strong focus on how differences in the external environment can significantly influence organizational survival and success (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Kostova et al., 2008; Xu & Shenkar, 2002).

Alternatively, with respect to the transaction cost economics (TCE) perspective, cultural differences are seen as a potential source of two forms of uncertainty—internal uncertainty and external uncertainty (Dow et al., 2020). Internal uncertainty refers to the concern that the management of the foreign MNE is not able to effectively monitor the local agents operating on its' behalf (Anderson & Gatignon, 1986). As a result, the firm is potentially exposed to both opportunistic behaviour and slack. Conversely, external uncertainty refers to the ability of the management to appropriately communicate with, understand, and monitor the external environment. This creates a form of information asymmetry relative to local competitors, increasing the chance that the foreign MNE may not be able to operate as effectively in that environment. Underlying all three of the preceding perspectives is the assumption that cultural differences increase transaction and information-gathering costs and risks; and thus, may decrease the efficiency of operations, increase intra-organizational conflicts, and result in poor implementation of organizational actions.

Researchers have also confirmed that greater cultural differences create more unique strains between partners (Bjo et al., 2007; Reus & Lamont, 2009). In addition, Malhotra et al. (2011) confirm that at high levels of cultural differences, firms experience higher risks and costs associated with ex ante screening of the target value and ex post enforcement of IB activities. Kang et al. (2017) also agree that cultural differences increase start-up costs for foreign firms to access local information. López-Duarte et al. (2016) further argue that cultural differences increase costs regarding knowledge transfer and conflict-solving. Importantly, these costs and risks increase as firms enter countries with greater differences or have more interaction with the cross-cultural context.

Some researchers (i.e., Zeng et al., 2013a) have also argued that to decrease these costs, MNEs often create well-prepared plans to support their foreign subsidiaries. Previous interaction with the cross-cultural context also provides 'memory' for firms to mitigate these costs and risks (Popli et al., 2016; Shenkar, 2001, 2012). However, Nadolska and Barkema (2007) report that MNEs, when managing their foreign subsidiaries, often inappropriately use applications that have only surface similarities to previous investments. Accordingly, when the differences are much higher, the consequences of the inappropriate use are magnified, and may even lead the foreign investments to failure. In a similar vein, Zeng et al. (2013b) state that the well-prepared plans or prior experience may be effective only at low levels of differences and overusing them for highly culturally different countries may lead to wrong assumptions and stereotypes. Hence, we expect that the solutions that help decrease these costs and risks, may be nonlinear in their effect. Consequently, we propose that as the cultural differences become very large, the ability to mitigate the downside aspects of the differences weakens, and the overall disadvantages increase at an accelerating rate.It is important to note here that with respect to foreign divestment, all of the preceding theoretical perspectives yield a similar prediction—that cultural differences tend to be associated with an increase the probability that a foreign subsidiary is divested.

This perspective—i.e., that cultural differences have a negative effect on the internationalization of firms—is reinforced by multiple meta-analyses (Beugelsdijk et al., 2018; Magnusson et al., 2008; Reus & Rottig, 2009; Rottig & Reus, 2017; Tihanyi et al., 2005). While the empirical results of these meta-analyses indicate a weak effect, the overall effect does appear to be consistently negative. It appears that cultural differences result in a variety of challenges for firm's internationalization. Our own literature review, focussing more specifically on the impact of cultural differences on foreign subsidiary divestment, supports this. As already mentioned, Table 1 summarizes 27 studies between 1996 and 2020 that have tested the relationship between cultural differences and foreign subsidiary divestment. From within that sample, a total of 16 statistically significant positive effects were reported, compared to only three statistically significant negative effects.

2.3.3 The Net Impact of Cultural Friction on Foreign Divestment

With respect to the impact of cultural differences on foreign subsidiary divestment, we combine the two preceding perspectives—i.e. the benefits increasing but at a diminishing rate and the disadvantages gradually accelerating—essentially yields a U-shaped relationship (Haans et al., 2016). At low levels of cultural differences, the realized benefits of these differences rise faster than the costs; and thus, the net benefit to the foreign firms from the synergistic benefits and the increased arbitrage and diversity rises. In addition, at low levels of differences, foreign firms compensate for the modest additional costs through benefits such as enhancing their internal capacities by integrating new knowledge stock, improving creativity, accessing more diversified resources, and avoiding domestic competition. Firms can also manage modest communication and coordination challenges easily because of the technological advancements, previous experience, and the advantages of memory effect. Well-prepared plans are also useful for firms to overcome low levels of cultural differences. Accordingly, we argue that the probability of foreign divestment will initially decrease as the cultural differences increase.

However, at higher levels of cultural differences, the realized benefits plateau and the additional costs begin to rise more rapidly, and the firm reaches a turning point. The additional costs of greater cultural differences eventually begin to exceed the realizable benefits; and as a result, the probability of divestment begins to increase. We argue that high levels of cultural differences dramatically increase the complexity of the communication and coordination challenges, increase the cost, time and effort required; and trigger conflicts between MNEs and their local learning sources for which well-prepared plans or accumulated experience are not helpful and may lead to stereotypes (Zeng et al., 2013b). When the cultural differences are excessive, subsidiaries become more difficult to manage. Ex ante and ex post costs and risks also increase at higher levels of cultural differences (Malhotra et al., 2011). Furthermore, firms have more difficulties in transferring their competencies to subsidiaries, because of higher differences in value and belief systems. Integrating more disparate knowledge stock may be also more challenging. Similarly, when subsidiaries are having more functions and interactions with the host distant cultures, the negative influence of cultural friction will probably be perceived as higher.

It is also worth mentioning that prior scholars have raised a paradox in the effect of cultural differences, i.e., low levels of cultural differences lead to higher levels of divestment, and conversely, high levels of the differences may secure for a higher level of survival (Evans & Mavondo, 2002; Magnusson et al., 2014; O’Grady & Lan, 1996; Zeng et al., 2013a). Fundamentally, prior scholars propose that operating at low levels of culturally different countries, MNEs and their managers may underestimate the effect of differences, and thus, encountering stronger competitions with local peers (Evans & Mavondo, 2002; O’Grady & Lan, 1996; Zeng et al., 2013a); thereby, leading to higher rate of failure. In contrast, MNEs and their managers may be well-prepared, conduct extensive research and planning when doing business in greater levels of cultural differences (Evans & Mavondo, 2002; Zeng et al., 2013a). In addition, operating in higher distant countries may provide unique opportunities that support foreign firms to stay longer (Evans & Mavondo, 2002).

2.3.4 The Role of Firm-Level Factors in the Cultural Friction Approach

The last step in the logic building up to our first hypothesis is to emphasize the importance of considering firm-levels factors, or the so-called ‘cultural interaction’ (Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Shenkar, 2001, 2012). Put simply, cultural interaction refers to the level of interface between the foreign firm and the host market cultural context. Shenkar (2001) argues that cultural differences may have little or no influence on foreign firms if there is minimal contact or interaction with the local culture. However, high levels of interaction can dramatically increase the impact of any cultural differences. In other words, cultural interaction magnifies the impact of cultural differences (Jong & Houten, 2014; Nooteboom, 2000). In this regard, when firms interact with business partners from different cultures or with the cultural distant systems, they learn from each other at various levels (Jong & Houten, 2014; Regnér & Edman, 2014). The firm level of cultural interaction with the distant context may also result in different levels of uncertainty and risks (Arregle et al., 2016). Slangen and Hennart (2008b) similarly confirmed that MNEs spend additional costs, which are firm-specific when operating in culturally distant countries. Thus, the cultural interaction is critical to consider when investigating the impact of cultural differences because it brings into the equation the actual interactions between specific actors, rather than just relying on national averages of their differences (Orr & Scott, 2008; Shenkar, 2012).

Elaborating further on the cultural interaction, Shenkar and his colleagues have repeatedly urged future studies to delve into how firms interact with the cultural distant context to define the impact of cultural differences (Luo & Shenkar, 2011; Shenkar, 2001, 2012). For instance, firms having more international or host countries’ experience are more knowledgeable about host markets, while higher levels of subsidiary density potentially brings supports from subsidiary networks at local countries (Kim et al., 2012). However, as noted above that these benefits do come at a cost. Collectively, we argue that at low levels of cultural distance, the firm-level factors can reduce the negative aspects and shift where the 'turning point' occurs, but at very high levels of cultural distance, they cannot totally blunt the negative aspects. Consequently, we propose the following:

Hypothesis H1: Ceteris paribus, there will be a U-shaped relationship between cultural friction and the divestment probability among foreign subsidiaries

2.4 Moderating Effect of Entry Mode

In this research, we further develop our understanding of the impact of cultural friction on foreign divestment by investigating the moderating effect of entry mode, i.e., acquisition vs. greenfield. In general, we argue that depending on different entry modes, firm levels of cultural interaction are likely be different, leading to different levels of cultural friction. In particular, Luo and Shenkar (2011), Shenkar (2012) argue that acquisitions require more cross-cultural interaction or contact (surface area), which in turn may magnify the impact of cultural friction.

While to our knowledge, no other paper directly addresses the issue of whether entry via acquisition moderates the impact of cultural friction on foreign divestment, these arguments are echoed and tested in two related streams of research. Firstly, the numerous researchers in the field of literature, concerning the direct impact of entry via acquisition (as opposed to an entry via greenfield investment) on foreign subsidiary survival and longevity (i.e. Benito, 1997; Delios & Makino, 2003; Hennart et al., 1998; Shaver et al., 1997), have argued that acquisitions involve greater integration problems because the acquired firms come with an existing organizational culture which may resist or clash with the organizational culture of the MNE making the acquisition. In general, this body of literature has empirically confirmed that entry via acquisition is negatively associated foreign subsidiary survival. However, it is important to remember here that these results pertain to the direct impact of entry via acquisition on survival, and not its moderating effect on the cultural differences—foreign divestment relationship.

The second stream of the extant literature, and one which is arguable more directly relevant to a moderating relationship, concerns the extent to which cultural differences influences a firm's preference for foreign entry via acquisition (i.e. Brouthers & Brouthers, 2000; Drogendijk & Slangen, 2006; Slangen & Hennart, 2007). Once again, this stream of research focuses on the potential clash between the Head Office (HO) of the MNE and the employees of the acquired subsidiary. They tend to argue that as nationally cultural distance increases, the employees of the acquired firm will trust the culture and practices advocated by the HO even less; and thus, the friction increases.

However, in another paper by Slangen and Hennart (2008a), concerning the impact of entry via acquisition versus greenfield on foreign subsidiary performance, they propose an interesting twist to the literature. They argue that the preceding focus on the potential clashes between the MNE HO and the subsidiary can be referred to, in terms of institutional theory, as 'internal conformity pressures' (or costs). However, they also add that a firm may be subject to 'external conformity pressures', referring to the interactions between the subsidiary and the local market that it operates in. Slangen and Hennart (2008a) argue that acquisition lowers the firm's external conformity costs because it does not suffer from the liability of newness. In essence, entry via acquisition confers upon the MNE a set of assets (i.e., local knowledge and reputation) that the MNE would not possess (at least in the same abundance) if it were to enter via greenfield investment. Moreover, as the cultural differences increase, the challenges of the MNE replicating those assets via greenfield investment increase; thus, the advantages of an acquisition increase. This line of argument would suggest that entering a market via acquisition would reduce the level of cultural friction.

The two aforementioned series of arguments make diametrically opposite predictions—as acknowledged by Slangen and Hennart (2008a)—with the key distinction being whether one focuses on the cultural differences between the HO and the subsidiary (i.e., the internal conformity pressures) or the cultural differences between the subsidiary and the local market (i.e., external conformity pressures). However, for the purposes of this paper we propose the Luo and Shenkar (2011) perspective that at lower levels of cultural distance, acquisitions involve higher levels of interaction, leading to higher levels of cultural friction. Consequently, the negative effect of lower levels of cultural friction on foreign divestment will be stronger, as opposed to greenfields. On the other hand, at higher levels of cultural distance, acquisitions involve higher levels of interaction, leading to higher levels of cultural friction, compared to greenfields. Consequently, positive effect of higher levels of cultural friction on foreign divestment will be stronger. Taken together, we propose that acquisition could make the curved effect of cultural friction on foreign divestment be steeper. However, we acknowledge that due to competing effects (i.e., internal conformity versus external conformity), an equally valid competing hypothesis could be made.

Hypothesis H2: Ceteris paribus, the U-shaped relationship between cultural friction and the divestment probability will be steeper when the firm enters the host country via acquisition

3 Research Methodology

3.1 Sample

The empirical data for this study comprises FDIs in the manufacturing sector made by Finnish firms from 1970 to 2010 and follows up on those investments to the end of 2017. We collected the Finnish MNEs’ information by using the Thompson and ORBIS databases, systematic analysis of the annual reports, press releases of the investing firms, the data gathered in FDI surveys and direct contact with investing companies to identify especially greenfield investments and closures of foreign units.

Finland is a particularly good country as the basis for such an investigation. Despite its small scale in the global arena, in 2018, the Finnish economy was the eleventh most competitive nation of 140 ranked countries (Global Competitiveness Report, 2018). As a result, the country, along with other Nordic countries, accounts for a significant amount of outward FDIs. In addition, the Finnish national culture (e.g., using the Hofstede and GLOBE frameworks) differs from the cultures in the United States, Japan, and other non-Nordic countries, making the sample an excellent venue for investigating cultural differences. The year 2017 is used as the cut-off year for new investments to avoid the bias of the 2-year honeymoon effects (Gaur & Lu, 2007; Wang & Larimo, 2020).

In total, 2215 investments were identified of which 1030 cases (46.5%) when later divested. We then excluded 191 cases because of missing data. Thus, the final sample comprises 2120 investments made by 269 firms in 40 different host countries. Within this sample, 964 cases (45.5%) were divested at the cut-off time (year 2017).

Among the observations, 1486 cases are acquired subsidiaries (70.1%). This portion is relatively similar to studies that have reported the acquisition entry form for Western-based companies (Barkema & Vermeulen, 1998; Dow & Larimo, 2011; Shaver, 1998; Shaver et al., 1997). In addition, two thirds of investments are made in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries (1,531 cases), while the United States (309), Sweden (257), and Germany (179) are the top three most frequent host countries in the sample. Because the study is limited to the investments made in the manufacturing sector (SIC 20–39), the sample is more homogenous than those in several other studies, which have included a variety of sectors (i.e., Demirbag et al., 2011; Meschi et al., 2016; Mohr et al., 2016). The 40 host countries are listed in Appendix 1.

3.2 Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study is the probability of foreign divestment, and it is operationalized as 1 for divestment and 0 for survival. A subsidiary surviving at the end of the observation is treated as a censored case and coded as the number of years between the establishment year and the cut-off observation year. This practice is common in the divestment literature (Getachew & Beamish, 2017; Kang et al., 2017; Peng & Beamish, 2019).

3.3 Predictor Variables

3.3.1 Cultural Friction

To maintain consistence with the original authors, our study follows the approach of Luo and Shenkar (2011) for calculating cultural friction. Luo and Shenkar (2011) propose that cultural friction represents the combined effect of national-level differences in culture—specifically the classic Kogut and Singh (1988) cultural distance index- and three firm-specific factors—the speed of international expansion within the host country, the sequence of investments within the host country, and the overall quantity of investments in host country (also referred to by Luo and Shenkar as the surface area to maintain the alliteration). These three firm-level factors collectively represent the level of ‘cultural interaction’. In effect, cultural interaction can be seen as a moderator of cultural distance in the same vein as Brouthers and Brouthers (2001) and others (Kang et al., 2017; Malhotra et al., 2011; Peng & Beamish, 2014; Wang & Schaan, 2008) who have explored other contextual factors that might moderate the impact of cultural differences.

In Luo and Shenkar's original formulation (2011), national-level cultural differences were measured using Kogut and Singh's (1988) national cultural distance index. However, instead of using Kogut and Singh’s Hofstede-based distance measurement, our study initially applies the more recent GLOBE-based cultural dimensions and combines the various dimensions of culture using the Mahalanobis distance technique (Berry et al., 2010). The GLOBE framework (House et al., 2004) is recommended because of its sample reliability, comprehensiveness, and updating (Popli et al., 2016; Venaik & Brewer, 2010). In order to test our main models, we initially apply the GLOBE Values version. The GLOBE Practices version and two other cultural distance frameworks, specifically Hofstede (1980) and Schwartz (1992, 1994, 1999) are then introduced as robustness checks. In terms of combining dimensions, Mahalanobis distance is arguably more appropriate when the dimensions are non-orthogonal, as is the case with most frameworks (Berry et al., 2010; Konara & Mohr, 2019). The distance component is labeled CD in our subsequent models, with a suffix to indicate the underlying cultural framework (i.e., CD—GLOBE-Values).

To measure the level of firm interaction with the culturally different context (i.e., the firm-specific portion of the cultural friction index), we draw upon Luo and Shenkar (2011) and combine three factors: the contact surface (N), the firms’ internationalization speed (V), and the sequence of the investment (G).

-

The contact surface, N, is measured as sum of all the active foreign investments held by the parent firm in the host country at the end of the corresponding year. This represents how large an overall interaction the firm has in that country.

-

The firm's internationalization speed, V, is measured as the increase in the number of active foreign investments held by the parent firm in the host country in the corresponding year. When MNEs adopt a lower speed (V) of foreign expansion, they are better able to align their experiential knowledge with host country risks and uncertainty.

-

The sequence of the investment, G, reflects the firm’s prior experience in the host country at the time the investment is made. It is computed such that the first investment a parent firm makes in a specific country is coded as 0. Subsequent investments in that country are coded as 1—1/k, which k is the order of the investment. In this regard, the first investment will have the value of k is 1 and the second investment has the value of k is 2, respectively. All investments made in the same year have a similar value of k. Luo and Shenkar (2011) denote G to represent the sequence of international experience but given that a lower value for G (i.e., earlier entry) implies a higher level of cultural friction, this variable is incorporated in the Luo and Shenkar (2011) index as (1-G).

Taken together, we follow Luo and Shenkar’s (2011) approach and calculate cultural friction, CF, as follows:

where e is constant and equal to 2.7183. As was the case with CD variable, the CF variable typically includes a suffix indicating the underlying cultural framework involved (i.e., CF—GLOBE-Values). It is also worth noting that as MNEs may keep expanding or change their investment portfolio to a local country over the year, value of cultural friction of a foreign subsidiary in a local country is subject to change due to changes of N, V, G. In Appendix 2 we provide practical examples of the cultural friction calculations.

3.3.2 Entry Mode (Entry via Acquisition)

The entry mode that the parent firm uses to initially establish each foreign subsidiary is employed in this study to examine its moderating effect on cultural friction (i.e., the main hypothesized relationship). In this instance, entry mode (Acquisition) is a dummy variable, and coded as 1 if the subsidiary was established via an acquisition, and 0 if it was established via a greenfield investment (Jiang et al., 2015; Song, 2014a).

3.3.3 Control Variables

Our main analyses—i.e., concerning subsidiary divestment—include controls variables, which collectively cover three operating levels (parent-level, subsidiary-level, country-level), and have been previously confirmed to significantly influence the foreign divestment probability. Table 2 presents details on the variable definitions, measurement, and relevant supporting citations. At the parent level, we control for the size, product diversification, and R&D intensity. At the subsidiary level, we control for the subsidiary age, the relatedness of the unit, and the equity ownership level (wholly owned subsidiary WOS vs. joint ventures IJV). At the country level, we control for the country’s political risk in the year of the initial investment, the subsequent change in that political risk, host country income level and GDP growth. Given that previous studies (e.g., Qian et al., 2008, 2010) confirm that firm internationalization has regional as well as global elements, we add an eleventh control variable—firm regional experience—to control for this aspect. One final control variable—host country economic development—is used as an instrumental variable in our first stage Probit models.

3.3.4 Model Specification

A Cox’s proportional hazards model (Cox & Oakes, 1984) is typically applied in the foreign divestment literature (Kang et al., 2017; Pattnaik & Lee, 2014; Song & Lee, 2017). An advantage of the Cox’s model is the suitability for the modeling of different forms of event history data because the model needs no assumption of functional form for the underlying hazard function relative to parametric models (Lee et al., 2019; Song, 2014b). The model also allows for various types of underlying survival functions because the baseline function is not specified in the model (Berry, 2013). As such, the hazard rate can be presented as log-linear functions of the various firm- and subsidiary-level covariates (Kang et al., 2017). However, instead of using the basic Cox model, which assumes no unobserved heterogeneity or event dependence, we apply a frailty Cox proportional hazard model to test the likelihood of foreign divestment (Berry, 2013; Lee et al., 2019). This frailty model accounts for cluster-specific homogeneities as multiple subsidiaries are often nested within one MNE (Austin, 2017; Lee et al., 2019). The frailty models also consider whether the same firm may suffer the hazard more than once as a result of unmeasured causes (Berry, 2013).

Endogeneity problem One important issue that we need to consider methodologically is that many scholars have highlighted a potential endogeneity concern with respect to the entry mode choice (acquisition vs. greenfield) variable (Mudambi & Zahra, 2007; Peng & Beamish, 2014; Shaver, 1998). As such, its moderating effect on the relationship between cultural friction and foreign divestment raises an endogeneity issue. Endogeneity poses some subtle issues to both empirical analysis and theoretical implications (Peng & Beamish, 2014). Therefore, we adopt the two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) approach by Terza et al. (2008) to address the potential endogeneity problem. The 2SRI has been confirmed to provide a general consistence for both linear and curvilinear situations (Berry, 2013; Peng & Beamish, 2014; Terza et al., 2008).

We specify our two-stage models as follows. In the first-stage model, we apply a Probit regression analysis with the choice to enter via acquisition (= 1) or via greenfield investment (= 0) as the dependent variable. The independent and control variables are the same as in our aforementioned hazard models, plus host country economic development as an instrumental variable (Peng & Beamish, 2014; Shaver, 1998). Host country economic development qualifies as a valid instrument because it is confirmed to involve acquisition choice (Bhardwaj et al., 2007; Chan & Makino, 2007; Peng & Beamish, 2014), while its effect on foreign divestment is not significant in previous studies (Chan & Makino, 2007; Meschi et al., 2016; Tsang & Yip, 2007).

In the second stage model, we apply a frailty survival analysis with foreign divestment probability, as described earlier, as the dependent variable. In this stage, we include all variables from the first-stage model, except for the instrumental variable, and add the first-stage residual. This allows us to address the potential endogeneity problem with the acquisition choice (Terza et al., 2008).

4 Findings

The descriptive statistics show a few high Pearson correlations among the variables; thus, the variance inflation factor (VIF) test is examined to diagnose any multicollinearity among variables. The result shows that multicollinearity is not a serious problem among our variables with the highest value at 1.76 (for firm size). Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables used in the study.

To test our hypotheses, we run our survival analyses with a 2-stage residual inclusion approach. Table 4 (Models 1 and 2) presents the first-stage Probit regression model with acquisition as the dependent variable. In Model 1, we include all eleven control variables to predict the acquisition choice, plus cultural friction. In Model 2, we include the aforementioned variables and the instrumental variable—host country economic development. The results show that nine of the 11 control variables have statistically significant coefficients in both models; and most important of all, cultural friction, and the instrumental variable both have statistically significant coefficients (p value < 0.01 and 0.001 respectively).

Table 5 (Models 3 to 8) represents our second-stage model, with the dependent variable as foreign divestment probability, to test the hypotheses. Model 3 is the base model with only the eleven control variables. Next, in Models 4 and 5, we add the cultural friction linear and square terms respectively to examine the first hypothesis (H1). Then, we test the second hypothesis (H2)—the moderating effect of acquisition choice—in Models 6–8, with the residual from the first-stage analysis (Model 2) included. In general, all the models are significant at high levels; and all but two of the eleven control variables have statistically significant coefficients.

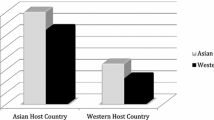

In hypothesis 1, we predict that cultural friction influences the foreign divestment probability following a U-shaped relationship. At low levels of cultural friction, it decreases the foreign divestment probability until a certain threshold; and from there on, at high levels of cultural friction, it increases the divestment probability. We refer to Haans et al. (2016) for guidance on how to examine such a U-shaped relationship. First, we check the significance and direction of both the linear and quadratic coefficients. In Model 5, our analysis shows that the coefficient of cultural friction is negative (β = -0.496, p value at 0.05 level), and the squared term is positive (β = 0.183, p value at 0.1 level) as predicted. Second, we analyze the slope of the curve on both ends of the data range, as suggested in Haans et al. (2016). More specifically, we adopt the following test β1 + 2*β2*XL and β1 + 2*β2*XH to provide evidence for the existing U-shaped relationship. In the formula, β1 and β2 are the estimated coefficients of the variable’s cultural friction and its squared term, respectively, and XL and XH represent the lowest and highest values of cultural friction in the data range, respectively. At the low end, the slope is negative and significant (-0.502, p-value = 0.025), and at the high end, the slope is positive and significant (0.504, p-value = 0.066). Third, we verify whether the turning point is located within the data range. To do so, we calculate the turning point (as—β1/2*β2), and it is equal to 1.35, which is well within the data range (0, 2.7). By way of example, this turning point is aptly illustrated by an actual case in our data set where a Finnish manufacturing firm invested in its sixth subsidiary (G = 1-(1/6) = 0.83) in Canada (CD = 4.52) in 1998. The firm was expanding rather aggressively in that region at the time and added a further five Canadian subsidiaries in the same year (V = 6). This brought them to a total of eleven Canadian subsidiaries by the end of the year (N = 11); thus, yielding a CF of 1.35. The resulting graph in Fig. 1 illustrates the relationship and provides evidence in support of Hypothesis 1.

As a result, we can confidently conclude that at low levels of cultural friction, the divestment probability decreases as the friction increases, but beyond a certain threshold, the foreign divestment probability increases as the cultural friction increases. In other words, we confirm that when operating at a very low level of cultural friction, MNEs may involve higher propensities of foreign divestment. This may reflect the O’Grady and Lane paradox (1996) where MNEs and their managers underestimate the degree of cultural differences. When the level of cultural friction increases to more moderate levels, MNEs appear able to manage the negative aspects of the cultural differences, effectively exploit the arbitrage opportunities, enjoy flexibility and diversity, and thus experience lower levels of divestment. However, this effect will be reverse past a certain threshold. That is, when operating at higher levels of cultural friction, foreign firms may encounter much higher transaction costs and more difficulties in exploit local resources, while well-prepared plans may lead to stereotypes and the arbitrage opportunities are narrower.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that acquisition choice will steepen the U-shaped relationship between cultural friction and the foreign divestment probability. In essence, we propose that the acquisition may both magnify the negative effects and enhance the benefits that firms may achieve at a particular level of cultural friction. Accordingly, Model 6 tests the direct effect of the acquisition on the probability of divestment. Models 7 and 8, respectively, test the moderating effect of acquisition choice on both the direct and quadratic forms of the cultural friction–foreign divestment relationship.

In keeping with H2, and following the methodology recommended by Haans et al. (2016), we expected that the interaction term between acquisition and cultural friction—quadratic effect would be significantly positive; thus, steepening the U shape relationship confirmed in Model 5. However, our expectations are not supported. In Model 6, acquisition does not appear to have any significant effect on foreign divestment, and this holds true for all subsequent models as well. In addition to that, the coefficient for the moderation of the direct effect of cultural friction is positive but not statistically significant in Models 7 and 8. Similarly, the direction of the coefficient for the moderation the quadratic effect is negative, but again non-significant. Thus, while these results hint that acquisition might modify the U-shaped effect of cultural friction, none of the interactions (linear and squared terms) are statistically significant. Therefore, our analysis does not support H2. We observe that entry via acquisition appears to neither influence the likelihood of foreign divestment, nor moderate the influence of cultural friction on foreign divestment.

Although the preceding results, which include a correction for selection bias, do not support H2, we feel that it is important to emphasize that earlier analyses that did NOT include a bias correction did indicate both a positive direct effect for acquisition and a moderating effect.Footnote 3 While we strongly endorse including a bias correction, these earlier results serve as an important caution for researchers. Although a simple interrogation of the data might indicate an important relationship (e.g., the role of entry via acquisition in our models), more subtle techniques such as two stage models correcting for sample bias are critical in determining the “true” state of affairs. In some respects, these results (i.e., both the absence of support for H2 and the misleading role of the acquisition variable) should not be surprising. While numerous prior studies (i.e., Benito, 1997; Delios & Makino, 2003) have found that acquisition plays an important role in subsidiary survival, most of these studies have not controlled for endogeneity. To our knowledge, only Shaver (1998) has explicitly used a two-stage correction factor for acquisitions, and indeed his work yields similar results to ours—i.e., the effect of the acquisition variable disappears after controlling for endogeneity.

To assist in interpretation, we further plot the relationship between cultural friction and the hazard ratio of divestment with the baseline of the survival model (h0) to describe the effect of cultural friction on the divestment probability in the time perspective (Fig. 2). As such, Fig. 2 presents three dimensions: cultural friction, the hazard ratio of the subsidiary, and the subsidiary age; and depicts a relationship that is initially negative and then positive as cultural friction increases. The U curve is consistent with the differing levels of divestment probability over time.

4.1 Post Hoc Robustness Tests

In addition to the analyses relating specifically to testing the hypotheses, we have also conducted two sets of robustness tests.

4.1.1 Testing the Impact of Cultural Differences with Other Cultural Frameworks

The first set of robustness tests involves replicating our results for Models 4 and 5 (Table 5) using alternative cultural frameworks. First, we replicate our results using the GLOBE-Practices measures, in place of the GLOBE–Values measures (Models 9 and 10 in Table 6). Next, we replicate our main models with the 4-dimension version of Hofstede’s framework (Models 11 and 12 in Table 6).Footnote 4 This latter replication is particularly relevant given Luo and Shenkar’s (2011) original formulation, where they proposed measuring friction by using the Hofstede cultural dimensions. We also conduct the same analyses using the Schwartz (1994) cultural dimensions—please see Models 13 and 14 respectively. The Schwartz’s cultural framework is relevant among IB studies because it overcomes several apparent limitations of Hofstede’s work (Drogendijk & Slangen, 2006; López-Duarte & Vidal-Suárez, 2013). The empirical results indicate that when using the cultural friction approach, the results concerning the role of cultural friction appear to be consistent across different cultural frameworks. The U-shaped relationship is supported in all cases. However, the next robustness test provides an interesting caveat to this conclusion.

4.1.2 Comparing Cultural Friction Versus Cultural Distance

Given that the cultural friction index that we are exploring in this paper includes cultural distance as one element, simply confirming the significance of the cultural friction coefficient does not prove that the cultural friction approach is superior to the classic approach of measuring cultural distance. One needs to unpack the index and ensure that both the direct effect of firm-specific elements of the index and their moderating impact on the cultural distance component of the index are significant. In particular, the moderating term needs to be significant to justify combining the two elements multiplicatively into a single index.

As a result, in Table 7, we decompose the cultural friction index into two elements. We begin with Model 4 as reported earlier in Table 5; however, in Model 15, we then remove the cultural friction metric, and replace it with the corresponding cultural distance metric (CD—GLOBE Values). It is important to note here that while Model 4 does allow us to make a visual comparison of the relative impact of cultural friction and cultural distance, strictly speaking it does not allow us to determine whether one approach is statistically superior to the other as they are not nested models. Nevertheless, inspection of Model 4 is informative for a special reason—the coefficient for cultural friction is statistically significant (– 0.126, p < 0.10), but in opposite direction to the cultural distance coefficient in Model 15 (0.192, p < 0.01)! This reversal of the direction is particularly unexpected given that CD—GLOBE Values is a component of the CF—GLOBE Values index. However, Models 16 and 17 partially clarify the situation by unbundling the friction index.

Models 16 and 17 are designed to allow us to statistically compare the relative contributions of cultural friction and cultural distance by capitalizing on the fact that cultural distance index (CD) is a subset of the overall cultural friction index (CF). Thus, we can create a series of nested models—Models 15, 16 and 17. We do this by splitting the friction index into three parts:

-

the cultural distance component (CD),

-

the firm-specific component of ‘cultural interaction’, which we labeled as NVG, and

-

the interaction term between the two (z (CD x NVG).

Specifically, NVG = eV(1−G) * N. This NVG component reflects the integrated effect of the contact surface (N); the speed (V), and the stage (G); and thus, represents the firm-level context variables. The interaction term (z (CD x NVG)) is created by re-centered both of the first two components (i.e., CD and NVG) and multiplied their z scores together to create a moderating variable.Footnote 5 This moderating variable is in effect the measure of whether the firm-specific context variables magnify (i.e., moderate) the impact of cultural differences (as measured by a Kogut and Singh style cultural distance index). However, quite fortuitously, Models 16 and 17 also allow us to untangle the surprising results mentioned earlier concerning the contrast between Models 4 and 15.

Model 16 is the first step in the process where we add to the model only the direct effect of the cultural interaction term (NVG). In Model 16, the coefficient for cultural distance (CD) is still positive and statistically significant (+ 0.195, p < 0.01), consistent with Model 15. However, the coefficient for NVG is negative and statistically significant (– 0.070, p < 0.05)—i.e., the surprising negative impact on divestment probability appears to the direct effect of the cultural interaction term (NVG). In Model 17, when the interaction term is added, the coefficients for the direct effect of cultural distance (CD) and cultural interaction (NVG) remain broadly the same as in Model 16, and the coefficient for the interaction between the two (z (CD x NVG)) is positive and significant coefficient (+ 0.132, p < 0.05). In effect, this latter coefficient in Model 17 for z (CD x NVG) confirms Shenkar and Luo’s original proposition—that the firm-specific degree of cultural interaction positively magnifies the impact of cultural differences. Thus, strictly speaking cultural interaction is critical. Moreover, the statistical significance of Model 17 over Model 3 (Δ Chi Sq = 8.746, p-value < 0.05) indicates that the cultural friction approach of incorporating the degree of cultural interaction (NVG) appears to provide a more accurate prediction of subsidiary divestment. However, the elephant in the room is still the surprising negative direct effect of the NVG variable.

To expand on these findings even further, we repeat our previous testing with other three cultural frameworks and the results are reported in Table 8. In each instance, we again split the friction index into three parts: the cultural distance component (CD) and the firm-specific component (NVG), and the moderating term (z (CD x NVG)). The most important insight here is that the statistical significance of cultural distance metric varies dramatically depending on the cultural framework employed. The Schwartz framework (Models 22 and 23) yields results broadly consistent with our GLOBE-Values results (Models 16 and 17). In contrast, for the other two cultural frameworks—GLOBE-Practices and Hofstede—neither the distance terms, nor the moderating terms, are statistically significant (Models 18–21). Indeed, it would appear that for these later two cultural frameworks, the significant cultural friction results reported Table 6 are primarily drive by the predictive power of the NVG term. However, we want to strongly argue that these anomalous results do not imply a weakness or flaw in the cultural friction approach. To us, the core issue here is a fundamental weakness in some of the underlying distance frameworks—at least with respect to predicting subsidiary divestment. This is a concern that has been echoed by numerous commentators stretching from Shenkar (2001) to Maseland et al. (2018). Even if one adopts the cultural friction approach, one still needs to be cautious about which cultural framework it is based on.

4.1.3 Other Post hoc tests

In addition to the two aforementioned sets of robustness checks, we have also carried out several minor robustness checks, for which we only report the results in the Appendices. First of all, the GLOBE group (House et al., 2004) also aggregate countries into ten clusters based on their cultural dimensions. Using these clusters, we re-structure our database and rerun main models at cluster level, instead of country level. It is important to note that by doing this, foreign investments of Finnish MNEs to other Nordic country (within the same cluster) are coded as domestic investments. The results remain largely similar as cultural friction has a curved effect (U-shaped) on foreign divestment. We present the results in the Online Appendix 3. In a final set of robustness checks, we further examine the divestment rate between subsamples with different economic development levels, based on the OECD categories. The results are robust in the subsamples. For brevity, we do not report these results.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

IB scholars have traditionally proposed that cultural differences, measured using the distance approach, increase the subsidiary divestment propensity. However, as mentioned earlier, the empirical studies to date concerning this proposed relationship have yielded ambiguous results. This ambiguity has led to criticism of the negative bias among cultural studies and of the validity of the cultural distance construct. As such, we advocate for a switch to cultural friction, a concept that has been proposed by Shenkar (2001, 2012) and others (Koch et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2019). In keeping with this call, we explore in this paper whether the cultural friction approach might help resolve some of the ambiguity. While the concept of cultural friction has received substantial attention in terms of commentary (i.e., Shenkar, 2012; Shenkar et al., 2008), formal testing of the index proposed by Luo and Shenkar (2011) has been extremely limited. We also embrace the call of Stahl and Tung (2015) and the POS perspective, and explore whether cultural differences may have a positive effect, as well as a negative effect on firm internationalization. In particular, we suggest that depending on the level of cultural friction, cultural differences may provide more benefits than challenges to foreign subsidiaries, leading to the curvilinear influence on the subsidiary divestment probability. In embracing and exploring these two issues, along with other more minor innovations, we posit that our paper makes several important, although at times unexpected, contributions to the literature.

6 Theoretical Contributions