Abstract

In this study, we use an empirical example to demonstrate how a multi-stage pattern matching process can inform and substantiate the construction of partial least squares (PLS) models and the subsequent interpretation of and theorizing from the findings. We document the research process underlying our empirical investigations of business – civil society collaborations in South Korea. The four-step process we outline in this paper can be used to ensure the meaningfulness of the structural model as well as to maximize the use of PLS for theorizing. This methodological advancement is particularly helpful in situations when literature reference points exist, but further contextual information may add nuances to prevalent knowledge. The findings from the qualitative flexible pattern matching part of the study prompted us to conduct a multi-group analysis. The resulting path changes in the base model led to the identification of four partnering strategies for business-CSO collaborations: (1) partnering for visibility; (2) partnering for compliance; (3) partnering for responsibility outsourcing; and (4) partnering for value co-creation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper uses an empirical example to demonstrate how a multi-stage pattern-matching process can inform and substantiate the construction of partial least squares (PLS) models and the subsequent interpretation of and theorizing from the findings. We document the research process underlying our empirical investigations of business – civil society collaborations in South Korea. We first outline why and how a multiple-pattern matching process can enhance the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). We then provide a framing for our empirical study and discuss how the study contributes to the international business and international management literature.

PLS-SEM as a method and SmartPLS as a software tool (Ringle et al. 2015) have rapidly gained popularity over the past decade. This is partially due to PLS-SEM’s suitability for predicting and theorizing, and its ability to deal with complex models, estimate formative constructs, and handle smaller sample sizes, among other features (Richter, Cepeda, et al. 2016; Ringle et al. 2020). However, despite the method’s high level of sophistication, its relative flexibility and the user-friendliness of the software have generated some unintended consequences (Zeng et al. 2021). Although PLS-SEM was originally designed to facilitate theory development through the exploration of data (Richter Sinkovics, et al. 2016; Ringle et al. 2020), researchers still need to bear in mind that an inductive approach in quantitative analysis requires sound conceptualization and operationalization and an adequate execution of data collection (Sinkovics 2018; Trochim 1989; Zeng et al. 2021; Wible and Sedgley, 1999). Therefore, it is important to focus more attention on methods and techniques that can be applied at the beginning of the research process to pave the way for generating sound PLS models and to enhance the benefits of theorizing with PLS (cf., Sinkovics 2016, 2018; Sinkovics et al. 2021b).

In this study, we draw on the pattern-matching framework to demonstrate how the use of qualitative techniques can strengthen the conceptualization and theory-building aspects of PLS. The overall pattern-matching process can be divided into three stages: partial, flexible, and full pattern matching (see Appendix Fig. 5 for an overview). By bringing together all three stages, our study demonstrates how they inform each other (see Fig. 1), specifically, how the first two stages support the development of a PLS model and the subsequent theorizing based on the empirical findings from 215 firm responses to a survey.

The multi-stage pattern matching process underlying this study. Source: adapted from (Sinkovics 2018)

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) frequently interact with sociopolitical stakeholders such as civil society organizations (CSOs) across their home as well as host countries (Sun et al. 2021). These interactions are considered an aspect of MNEs’ non-market strategies, and they contribute to MNEs’ competitiveness by reducing challenges associated with social, political, and institutional contexts (Mellahi et al. 2016). A growing number of international business studies have highlighted non-market strategies as an integral part of MNEs’ overall international business strategy (Boddewyn and Doh 2011; Cuervo-Cazurra et al. 2014; Doh et al. 2015, 2017; Kobrin 2015). Lucea and Doh (2012) propose that if MNEs are to design non-market strategies that appropriately fit their non-market context, they need to pay attention to four sociopolitical dimensions, namely, stakeholders, issues, networks, and geography. Therefore, there is a need to match what we know about these dimensions in frequently explored research settings such as the United States and Europe to knowledge generated in less frequently explored settings such as South Korea and other Asian and African geographies (cf., Doh et al. 2015). An additional factor that adds urgency to these explorations is the United Nations’ (UN 2015) stance on the importance of cross-sector partnerships for the attainment of the sustainable development goals (Bäckstrand 2006). In this paper, we define business–CSO collaboration as “a system of formalized cooperation between several institutions [involving at least one firm and one CSO], based on a legally contracted or informal agreement, links within cooperative activities and jointly adopted plans” (Wyrwa 2018, p. 123).

We chose South Korea as our research context because of the highly influential role that CSOs play in the country’s political and business environment. Understanding this context could help foreign MNEs in South Korea reduce institutional distance and design better non-market strategies. For instance, Kim et al. (2013) highlight a comment by a South Korean Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) manager: “we get too much political influence on CSR. I think this is typical in Korea … so businesses are not free to do what they think they should do anymore. Businesses have to pay attention to these pressures (from CSOs)” (p. 2584). As exemplified by this quotation, an important characteristic of South Korean CSOs is their active and direct participation in politics, both at an individual and group level. Many even become politicians themselves, and as a group they have been involved in the conception and running of past administrations.

Therefore, on a conceptual level, our study contributes to the international business and international management literature by furthering understanding of how the factors that drive the formation of business–CSO collaborations influence firms’ collaborative behavior and ultimately the outcomes of collaboration in the South Korean context. The findings hold important implications for MNEs aiming to expand into the South Korean market given the extent to which CSOs actively shape the sociopolitical environment. Further, an understanding of how South Korean firms engage with CSOs in their home country will aid future theorizing about their collaborative behavior with CSOs in host countries.

2 Partial and Flexible Pattern Matching to Pave the Way for Structural Model Specification

Appendix Fig. 5 provides an overview of the three stages of pattern matching. Partial pattern matching is completed either in the theoretical realm, where the researcher works with the literature to identify initial theoretical patterns, or in the observational realm, where the researcher starts with empirical observations to identify theoretical patterns (Bouncken et al. 2021; Shah and Corley 2006; Sinkovics 2018). Flexible pattern matching builds on partial pattern matching (Sinkovics 2018), either within the same study or in a subsequent study. Initial theoretical patterns are deduced from the literature or a previous inductive study and matched to observed patterns in empirical data. Therefore, flexible pattern matching combines a deductive and an inductive component. In other words, it seeks to identify matches and mismatches between initial expected patterns based on the literature and observed patterns that emerge from the empirical data while simultaneously allowing new patterns to emerge from the data (Bouncken et al. 2021; Sinkovics 2018). The third stage of pattern matching is full pattern matching. This aims to determine which alternative theory best explains an empirical observation. Structural equation modelling arguably represents the highest level of full pattern matching to date because it involves pattern matches at the structural level as well as the measurement level (cf., Hair et al. 2017; Sinkovics 2018).

Figure 1 demonstrates how we used the different stages of pattern matching to construct our structural (and later, measurement) model. Step 1 involved a systematic literature review (see Appendix Table 5 for the protocol). The aim was to obtain an understanding of what is known in the literature about business–CSO collaborations and what theories are commonly used to underpin investigations on this phenomenon. We conducted this literature review with the aim to derive an initial framework – that is, a collection of theoretical dimensions as a starting point for our structural model specification. In step 2, we conducted interviews and applied a flexible pattern-matching analysis technique to check the relevance of the theoretical dimensions that we had identified from the literature to our study context. This was necessary since most studies we identified were conducted in the United States and Europe, and we needed to ascertain that those insights were relevant for our South Korean context. Flexible pattern matching further allowed us to explore whether there were any theoretical dimensions that the literature had not yet uncovered but that were important in this context. Step 3 then entailed the finalizing of our structural model and the hypotheses.

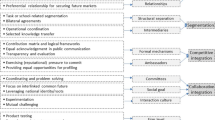

Appendix Table 7 lists the main theoretical dimensions, the corresponding operationalizations, and the expected theoretical patterns that we identified from the literature review. The three main dimensions correspond to the three phases of business–CSO collaborations: (1) formation, (2) implementation, and (3) outcomes (e.g., Selsky and Parker 2005). The formation phase refers to the factors that drive organizations to collaborate with CSOs. Prior studies suggest two main drivers (e.g., Dahan et al. 2010; Weber et al. 2017): The pressure from external stakeholders to collaborate with CSOs and the desire to gain access to the resources of CSOs. These drivers are linked to two main theories in the literature – stakeholder theory and the resource-based view.

The implementation phase of business–CSO collaborations may be linked to the collaborative behavior displayed by partners to achieve their shared objectives (Heckman and Guskey 1998). Our review of the literature uncovered three main concepts: interorganizational connectivity, shared resources, and trust in CSOs’ competence and good intentions (Jiang et al. 2015; Rivera-Santos and Rufín 2010; Weber et al. 2017). Interorganizational connectivity refers to “the communication and interaction mechanisms and relational structures that support the back-and-forth flow of knowledge and ideas” (Sinkovics et al. 2019, p. 132) in collaborations. The resource-sharing dimension includes the sharing of knowledge, capabilities, materials, human resources, and social capital. Lastly, the trust dimension can be broken down into “goodwill trust,” that is, trust that the partner wishes to contribute to the collaboration, and “competence trust,” that is, trust that the partner has the capability to contribute to the collaboration (Jiang et al. 2015; Lui and Ngo 2004). Finally, the outcomes phase of business–CSO collaborations encompasses two performance dimensions: business and social performance of the collaboration.

The fourth column in Appendix Table 7 offers sample comments to demonstrate observed patterns in the interview data (see Appendix Table 6 for an overview of firm characteristics in our sample). The last column in Appendix Table 7 provides the outcome of the flexible pattern match, that is, how the observations from the qualitative data compare against prior research results or theoretical expectations derived from the literature. The matches, mismatches, and emerging aspects provide a quality check for the meaningfulness of the structural model and form the basis for our hypotheses. Therefore, the hypotheses formulated below, in step 3 of the multi-stage pattern matching process (see Fig. 1), are partly grounded in the literature (step 1 in Fig. 1 corresponding to columns 1–3 in Appendix Table 7) and partly the result of theorizing based on the qualitative data analysis via flexible pattern matching (step 2 in Fig. 1 corresponding to columns 4–5 in Appendix Table 7). Figure 2 provides the structural model and the hypotheses.

2.1 The Relationship Between Stakeholder Pressure and Collaborative Behavior in Business–CSO Collaborations

Although our findings largely match the predictions from the literature regarding the fundamental relationships between stakeholder pressure and collaboration with CSOs (see Appendix Table 7), we found some differences in intensity stemming from the South Korean context. Specifically, whereas stakeholder pressure is expected to lead to a certain degree of connectivity between the firm and the CSO in most institutional contexts (c.f. Pagell et al. 2010), this relationship is likely to be much stronger in South Korea. This is a consequence of targeted government initiatives and the prominent and influential role of CSOs (Kim et al., 2013). Therefore, we hypothesized a positive relationship between stakeholder pressure and investment in interorganizational connectivity with the CSO.

Hypothesis 1a: A positive association exists between stakeholder pressure and investment in interorganizational connectivity

Our findings also corroborate evidence from other contexts that government-driven business–CSO collaborations may lead to resource sharing. This is because both the firm and the CSO may be required to sign written commitments to contribute resources to a given project (cf., Pratt Miles 2013). Consequently, the CSO may register a complaint if the firm does not share resources to the extent stipulated in the agreement, which in turn may lead to strict penalties (Tripsas et al. 1995). Hence, firms may be obliged to share resources with a CSO because of the government’s intervention. If a business–CSO collaboration is formed owing to consumer or client pressure, the parties may form joint teams to address the underlying issue as well as to perform public communication activities. Such activities may include joint promotional events, marketing campaigns, publications, and media briefings (Shumate and O’Connor, 2010). We found evidence in our qualitative data to support these expected patterns in the South Korean context. Further, we found that the resource-sharing level is higher when the competence level of the CSO is high.

Hypothesis 1b: A positive association exists between stakeholder pressure and investment in resource sharing with the CSO

However, stakeholder pressure to collaborate with CSOs may lead to low levels of goodwill trust in CSOs (cf., Jiang et al. 2015). This occurs because a firm may feel too concerned about the motives of a CSO to initiate collaboration, for example, a CSO’s intention to use information received through collaboration to fuel future criticism. Further, when collaboration is forced, a firm does not tend to have the opportunity to perform due diligence with respect to the CSO’s ability to contribute to the project outcome (cf., Rivera-Santos and Rufín 2010). We found evidence of this in our qualitative data. Specifically, when there is government pressure to collaborate with a specific CSO, firms do not feel they are in a position to refuse the collaboration, despite having little opportunity to gauge the CSO’s competence. This may lead to problems during the collaboration and reduced general trust in CSOs in future collaborations.

Hypothesis 1c: A negative association exists between stakeholder pressure and the level of trust in CSO.

2.2 The Relationship Between Accessing CSO Resources as a Driver for Collaboration and Firms’ Collaborative Behavior

We also found support for the general proposition that when a firm collaborates with a CSO to access its resources, it is more likely to build interorganizational connectivity. This is because building interorganizational connectivity allows partner organizations to understand the depth and breadth of each other’s resources (Ferreras-Méndez et al. 2015) as well as identify who holds the required knowledge in each organization. In general, CSOs possess knowledge about local communities or population segments on the fringes of the mainstream market. CSOs are also likely to have network ties with local community leaders (Dahan et al. 2010; Sinkovics et al. 2014). Further, in developing countries, CSOs are often hired by the government to design and deliver social projects on its behalf (Barr et al. 2005), and thus CSOs may possess high levels of social capital within government organizations (Den Hond et al. 2015). This can be leveraged by a firm to obtain regulatory approval and a “social license to operate” (Wilburn and Wilburn 2011). Since tacit knowledge is difficult to codify, it is mostly transferred through personal relationships (Nonaka 1994). Therefore, firms are required to implement communication strategies that facilitate information exchange between the two groups of employees.

Hypothesis 2a: A positive association exists between firms’ desire to access CSO resources and to invest in building interorganizational connectivity

We also found evidence to support that when a firm is driven to collaboration by the prospect of accessing CSO resources, it is more likely to implement strategies and routines that foster resource exchange. For instance, joint integrated teams allow partner organizations to become closer and access each other’s tacit knowledge (Lam 1997). Further, the presence of joint teams on public platforms and at public events signals a high degree of integration between CSO and firm, resulting in a better reputation. Our findings also indicate that co-location, such as shared office space, can further facilitate this process.

Hypothesis 2b: A positive association exists between firms’ desire to access CSO resources and firms’ desire to share their own resources in return

When a firm initiates a collaboration with a CSO to access the CSO’s resources, it is assumed that the firm is already aware of the potential of the CSO’s resources and is anticipating synergies between the two organizations’ resources. As opposed to situations in which the collaboration is stakeholder driven, a firm is more likely to undertake due diligence when the collaboration is motivated by a desire to access CSO resources. As a consequence, the firm will have a better understanding of the CSO’s level of expertise and capacity to achieve the overall objectives of the proposed collaboration (Rondinelli and London 2003; Seitanidi and Crane 2009). Therefore, when a collaboration is formed with a CSO to access the CSO’s resources without any pressure from external stakeholders, the role of trust in the CSO is likely to be more important for the collaboration (cf., Jiang et al. 2015) than when the collaboration is stakeholder driven.

Hypothesis 2c: A positive association exists between firms’ desire to access CSO resources and firms’ level of trust in the CSO.

2.3 The Relationship Between Collaborative Behavior and the Outcomes of Business–CSO Collaborations

In business–CSO collaborations, interorganizational connectivity is likely to play a bigger role than in the usual equity alliances. This is because of differences between the organizations in terms of culture, values, routines, performance measurement, leadership style, decision-making processes, and goals (Quélin et al. 2017). The findings from our interviews suggest that frequent and well-designed communication helps the collaborating partners to understand existing differences and fosters conflict resolution. Further, interorganizational connectivity also fosters a better understanding of the underlying issues that the project aims to address. Several respondents highlighted the importance of two-way communication and knowledge exchange to co-create solutions that were not only related to the company’s core business but also had significant societal implications. Examples include product design for the visually impaired or the design of environmentally friendly products. Therefore, interorganizational connectivity is expected to lead to positive business as well as social performance outcomes.

Hypothesis 3a: A positive association exists between investment in interorganizational connectivity and business outcomes in business–CSO collaborations.

Hypothesis 3b: A positive association exists between investment in interorganizational connectivity and social outcomes in business–CSO collaborations.

In the context of equity alliances, scholars have empirically confirmed a positive association between resource sharing and collaboration outcomes (Weber et al. 2017). Similarly, resource sharing in business–CSO collaborations is expected to lead to enhanced collaboration outcomes. CSOs often lack the financial resources required for their projects (Hale and Mauzerall 2004). Therefore, sharing financial and other resources with CSOs can be expected to lead to better social outcomes. Our interview data indicate that resource sharing may come in different shapes and sizes, including applying for government funds and co-designing products for an underserved population segment.

Hypothesis 4a: A positive association exists between a firm’s resource sharing with its CSO partner and business outcomes in the business–CSO collaboration.

Hypothesis 4b: A positive association exists between a firm’s resource sharing with its CSO partner and social outcomes in the business–CSO collaboration.

Based on the findings from the literature review, it is expected that a high level of trust in the CSO will lead to cost reductions in terms of legal, monitoring, and negotiation costs (Lui and Ngo 2004; Zaheer et al. 1998). In business–CSO collaborations, differences in objectives (Mars and Lounsbury 2009) can lead to delays in agreeing on the overall objectives of the collaboration and drafting its terms and conditions. Further, a high level of trust between partners is expected to facilitate discussion of social and business issues, including those external to the project. Moreover, when a firm’s trust in its CSO partner is high, it is more likely to draw on the partner in the product development process. Research and development–related information and product pipelines involve sensitive information that firms tend to protect (Dahan et al. 2010). While our interview data support the link between trust and the business outcomes of the collaboration, our findings suggest that trust in the CSO partner may be less relevant regarding social outcomes. Nevertheless, we hypothesize a positive relationship between trust and social outcomes to further test the theory in the second part of the study.

Hypothesis 5a: A positive association exists between a firm’s high level of trust in its CSO partner and business outcomes in the business–CSO collaboration.

Hypothesis 5b: A positive association exists between a firm’s high level of trust in its CSO partner and social outcomes in the business–CSO collaboration.

2.4 CSO Dominance and Firms’ Level of Standard Adoption

Two dimensions emerged during the flexible pattern matching process that seem to have an influence on how the relationships between our theoretical concepts play out. These are the level of dominance of a CSO within the industry and the level of standard adoption by the firm. The dominance of a CSO within the industry may be seen as a proxy for its experience and reputation. For example, one of our interviewees stated, “If a CSO is not dominant in a particular sector or domain [environmental or labor issue], it implies that they do not bring sufficient experience and knowledge to a particular collaborative project. When we collaborated with CSOs that were less influential in the past, we faced a lot of difficulties…”.

Conversely, the level of standard adoption by the partnering firm may be regarded as a proxy for the firm’s internal resources and capabilities that enables the firm to learn about and tackle social and environmental issues. The implementation of standards or other voluntary frameworks generally requires firms to develop processes, routines, and capabilities to learn about and address aspects of the targeted social and environmental issues. This in turn is expected to increase the level of value co-creation in the collaboration. The following comment from one of our interviews represents a case where there is no value co-creation: “We are not able to check every single step taken by the CSO in our project because of our resource constraints. As a small firm, we don’t have the time or human resources for that. We also don’t have much knowledge about what is required to fulfil these social and environmental standards. So, we just have faith in our CSO partner. We trust in what they are saying and what they are doing … and that the way they are carrying out the project will contribute to the community.” Examples of standards include the ISO 14000 suite covering environmental management and ISO 26000 Social Responsibility.

These two theoretical dimensions that emerged from the interview data can be used to create four scenarios: (1) Low standard adoption/Low CSO dominance, (2) High standard adoption/Low CSO dominance, (3) Low standard adoption/High CSO dominance, and (4) High standard adoption/High CSO dominance. Based on the qualitative data, we expected that the paths from the original model would change under these different conditions. However, we did not have sufficient data points to formulate hypotheses pertaining to how exactly the paths might be expected to differ across the four scenarios. Therefore, we drew on PLS-SEM’s suitability for exploration and conducted a multi-group analysis to examine whether – and, if yes, how – the paths changed across the four scenarios.

3 Full Pattern Matching with PLS-SEM

Step 4 in our multi-stage pattern matching approach encompasses the measurement model specification, model estimation, and results evaluation stages of the PLS-SEM analysis process (Ringle et al. 2020). We collected survey data between November 2018 and February 2019. We drew on the databases of two intermediary organisations – the CSR Forum and the CSR Academy in Seoul – to identify potential respondents (in total, 530 companies). The survey was sent to CSR managers by email. We also provided the option to complete the survey over the phone or offline (cf., Dillman et al. 2014). The survey was originally designed in English and then translated into Korean, which was validated by an accredited language expert.

We received a total of 224 responses (i.e., 42% response rate), out of which 215 were complete and valid. Table 1 provides an overview of the descriptive statistics. This distribution was in line with data from the National Statistical Office (2015), which shows that small and medium-sized enterprises in Korea account for 99.9% of the total number of Korean firms. More than half of the respondents (60.5%) considered their firms’ collaborations with CSOs to be either extremely important (31.2%) or very important (29.3%) (see Table 2).

3.1 Measures

All variables were measured using seven-point Likert scales, with 1 corresponding to strong disagreement and 7 to strong agreement. Stakeholder pressure was measured based on items involving a range of stakeholders, including (1) government, (2) supply chain, (3) CSOs, and (4) industry/trade associations (Van Huijstee and Glasbergen 2010). In most Asian countries, including South Korea, owing to their high power-distant culture, if a firm is “asked” or “invited” to collaborate by an organization with a presence in the regulatory, social, or business environment (most CSOs, supply chain collaborators, and government organizations fall into this category), this usually implies pressure. Access to CSO resources was measured by using items adapted from Dahan et al. (2010), comprising CSOs’ (1) social capital, such as networks and contacts, and (2) knowledge resources. The propensity of firms to build interorganizational connectivity was measured using items adapted from Jamali et al. (2011). Interorganizational connectivity was categorized into (1) project-specific, and (2) relation-specific interorganizational connectivity. The propensity of firms to share resources was measured using items adapted from Jiang et al. (2015), including (1) human resources, (2) knowledge resources, and (3) social capital in collaborations. The extent of trust in CSOs was adapted from Lui and Ngo (2004). The measurement items captured both (1) goodwill trust and (2) competence trust. Our dependent variables were the outcomes of business–CSO collaborations. The measures of social performance were adapted from Hansen and Spitzeck (2011), whereas the measures of business performance were adapted from Steckel and Simons (1992). We also controlled for firm size and past alliance experience. Firm size was measured in terms of the number of employees. Two dummy variables were created – “0” (or small-sized firms) if the number of employees was less than 500 and “1” (or large-sized firms) if the number of employees was ≥ 500. Similarly, “0” was created if firms had no past alliance experiences with CSOs and “1” if they had past alliance experiences with CSOs. Since our control variables were categorical, the effect of each dummy variable was analyzed via a bootstrapping procedure with a resample of 4,999 (Henseler et al. 2016). Results indicated that control variables did not exhibit any significant effect on dependent variables.

3.2 Common Method Bias

We employed the marker variable technique to address the potential issue of common method bias (Rönkkö and Ylitalo 2011). We chose the level of information technology to use as a marker variable because it was not theoretically correlated with any constructs in our research model. The mean correlation coefficient value for the marker item was 0.035, indicating an insignificant influence of common method bias. We further included this marker as a control variable (i.e., additional exogenous variable predicting each endogenous construct) in our PLS model (Rönkkö and Ylitalo 2011). We compared the results of the marker model with those of our baseline model. Since we noted minimal changes to the estimates for the path coefficients had occurred and all significant effects remained significant, we concluded that common method bias was not a concern in this research.

3.3 Measurement Model Assessment

First, we assessed item reliability using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) for each construct. CR is considered a more suitable measure of reliability for the PLS-SEM method (Hair et al. 2018). All constructs had CR and alpha values above 0.7, confirming a high level of internal consistency reliability (see Appendix Table 8). Second, discriminant validity was assessed based on the cross-loading criterion suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Third, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) is the only estimated model-fit criterion in PLS path modelling (Henseler et al. 2016; Hu and Bentler 1998). We found an SRMR value of 0.055, which indicated a good model fit for PLS-SEM analysis (Henseler et al. 2016). Overall, it may be concluded that we had a reliable and valid measurement model (Table 3).

Last, we evaluated endogeneity according to the systematic procedure proposed by Hult et al. (2018). The Gaussian copula approach (Park and Gupta 2012) to endogeneity testing was inapplicable owing to criteria violations; thus, we pursued endogeneity using the control variable approach in PLS-SEM (Hult et al. 2018). We applied two control variables, firm size and past alliance experience, in the model. According to Arndt and Sternberg (2000), firm size is an important factor influencing corporate behavior such as collaboration. Since small firms tend to lack resources, they are likely to engage in collaboration. Path coefficients between the control variables and the endogenous variable are explained in Appendix Table 9. The findings confirm that the control variables had no significant effect on the dependent variables. Therefore, we can conclude that this research had no endogeneity issues, and the findings confirm that the PLS-SEM model was robust.

3.4 Confirmatory Tetrad Analysis

We applied confirmatory tetrad analysis (CTA-PLS), widely considered an appropriate approach, to determine whether the latent construct was reflective or formative (Hair et al. 2017). This statistical measure is based on an assessment of construct indicators. The latent construct is considered reflective when all the tetrad values are non-significant (Hair et al. 2017). Appendix Table 10 provides the CTA-PLS results, indicating that none of the tetrads displayed a statistically significant difference from 0, which confirms the reflective nature of the constructs (Gudergan et al. 2008).

3.5 Assessment of the Structural Model

In accordance with Hair et al. (2013), the structural model was evaluated with R2, corresponding t-values, effect sizes (f2) and predictive relevance (Q2). First, we assessed the effect sizes, which signify the strength of relationship among variables (Appendix Table 11). Second, we performed a blindfolding procedure to evaluate the predictive relevance of the path model (Hair et al., 2018). We evaluated the predictive relevance of the latent constructs by adopting cross-validated redundancy Q2 and cross-validated communality Q2 (Fornell and Cha 1994). The Q2 values of all latent constructs were greater than zero, indicating the predictive relevance of the model (Appendix Table 11).

Appendix Table 12 and Fig. 3 provide an overview of the outcomes of hypothesis testing. With the exception of H1c indicating a positive association between stakeholder pressure and trust in CSOs, and H5b indicating a positive association between trust in CSOs and the social performance of the collaboration, we found support for all hypotheses in the main model. We discuss the results in more detail in the Discussion and Conclusions section.

3.6 Multi-Group Analysis

Appendix Table 13 provides an overview of the measurement invariance testing. We used a MICOM (measurement invariance of composite models) procedure involving a three-step approach: (1) configural invariance, (2) compositional invariance, and (3) equality of composite mean values and variances (Henseler et al. 2016). After completing the MICOM procedure, we conducted multi-group analysis across the four scenarios that emerged from the flexible pattern-matching aspect of the study based on high/low combinations of the focal firms’ standard adoption and high/low combinations of the CSOs’ dominance within the industry. Splitting the data along these dimensions resulted in sub-groups of 36, 38, 43 and 35 observations. All sub-groups exceeded the acceptable minimum sample size of 34 (Hair et al. 2018). The level of adoption of standards and CSO dominance were measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Extremely), and a cut-off value of ≥ 4 (median) was used to determine groups.

Figure 4 provides a graphical overview of the findings, while Appendix Table 14 presents the standardized coefficients and t-values. Table 4 summarizes R2 values and the effect sizes for the full model as well as for the four models for each scenario.

The findings tell a compelling story demonstrating the power of SmartPLS for theorizing and pattern matching at the highest level (cf., Liu et al. 2020; Sinkovics, 2018; Sinkovics et al., 2021b). We discuss the findings and their implications in the next section.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we employed a multi-stage pattern-matching process to identify from the literature the main dimensions that shape the outcomes of business–CSO collaborations and examine to what extent and how they apply in our specific study context, South Korea. The underpinning rationale for combining qualitative and quantitative methods in this study was to support the process of theorizing in stages, and specifically to ensure the meaningfulness of the structural model as well as to maximize the use of PLS for theorizing. This methodological advancement is particularly helpful in situations for which literature reference points exist but further contextual information may be required to add nuances to prevalent knowledge. The findings from the qualitative flexible pattern-matching stage of the study revealed that although the general theoretical concepts and the relationships between these concepts may largely hold in the South Korean context, they may mask a more complex and nuanced story. This can be largely explained by the unique history and strong role of civil society in South Korea resulting in a high level of trust of citizens in CSOs (cf., Bae and Kim 2013; Willis 2020).

Additionally, two dimensions emerged from the qualitative interviews that prompted us to explore them further with a multi-group analysis in SmartPLS. Without the flexible pattern-matching aspect of the study, we would not have identified these dimensions and the study would have lost some of its richness. The level of CSO dominance within the industry and the level of standard adoption of the collaborating firm provided us with four scenarios that in turn led to the identification of four partnering strategies in our data. In the remainder of this section, we describe and discuss the findings. We conclude by outlining the implications of the findings for MNEs wishing to enter the South Korean market and providing some suggestions for future research.

Although we hypothesized a negative association between stakeholder pressure and firms’ trust in CSOs, this relationship was consistently insignificant in the main model, as well as across the four scenarios. The other consistent result across all models (main model and models 1–4) was the non-significant relationship between trust in CSOs and the social outcomes of collaboration. Additionally, we found deviations from the main model in scenarios 1 and 2 (see Fig. 4). In scenario 1 (Low standard adoption/Low CSO dominance), only five paths were significant. The focal firm’s desire to access CSO resources had a positive association with interorganizational connectivity and resource sharing. Interorganizational connectivity in this scenario only had a significant impact on the social outcome of collaboration, whereas resource sharing had a significant impact on both business and social outcomes. In scenario 2 (High standard adoption/Low CSO dominance), neither stakeholder pressure nor firms’ desire to access CSO resources had a significant impact on trust in CSOs. Additionally, trust in CSOs in this scenario only had an impact on the business outcome of the collaboration. The effect sizes provided in Table 4 helped us theorize about the implications of these results.

In general, (see full model and models 2–3 in Table 4), stakeholder pressure to collaborate was less effective in driving firms’ collaborative behavior in a business–CSO partnership than firms’ motivation to access CSO resources. Further, in the presence of stakeholder pressure to collaborate, the importance of trust in CSOs seemed to be crowded out by the importance of satisfying the stakeholder that exercised the pressure. This was especially relevant in scenarios 2 and 4 where the focal firms had a high level of standard adoption and, by extension, a higher visibility to stakeholders. In these two scenarios, stakeholder pressure had a medium effect on interorganizational connectivity and a small effect on resource sharing. Investment in interorganizational connectivity would be necessary to demonstrate sufficiently to stakeholders that they fulfil their responsibilities in the partnership and thus comply with societal expectations, which would be required to obtain or retain their social license to operate (cf., Prno and Slocombe 2012; Wilburn and Wilburn 2011).

However, in scenario 3, the partnering CSO had low dominance in the industry, whereas in scenario 4 partner CSOs had high dominance. The dominance of CSOs seemed to influence the perceived trust of the focal firm in their CSO partner’s competence and goodwill and in turn the extent to which there was an attempt to co-create value. In scenario 4, trust in the CSO partner had a strong effect on the business outcome of the collaboration, whereas in scenario 2 it only had a medium effect. Further, in scenario 4, firms’ motivation to access CSO resources seemed to be more substantial than in scenario 2. This is evidenced by the significant path between the desire to access CSO resources and the level of trust in CSOs, as well as the medium effect of firms’ motivation to access CSO resources on their propensity to share their resources with the CSO. In scenario 2, this effect was small. This implies that focal firms in scenario 2 used their partnerships with CSOs strategically, yet not for co-creating solutions. Based on these insights, we can label the partnering strategy in scenario 4 “partnering for co-creation” and the partnering strategy in scenario 2 “partnering for compliance.”

In scenarios 1 and 3, firms had a low level of standard adoption. However, in scenario 1, firms partnered with non-dominant CSOs, whereas in scenario 3, firms partnered with dominant CSOs. Again, the role of trust in a business–CSO collaboration appeared to play a more important role when partnering with dominant CSOs. In scenario 3 (Low standard adoption/High CSO dominance), firms’ trust in their CSO partners had a strong effect on the business outcomes of the collaboration. Interestingly, only interorganizational connectivity had a noteworthy, even if small, effect on the social outcome of the collaboration, despite the fact that the path from resource sharing to the social outcome was significant. Firms in this scenario had little knowledge and experience with social and environmental issues. Therefore, they relied heavily on the CSO partner to implement the project. The strong effect of trust on business outcomes combined with the small effect of interorganizational connectivity and resource sharing on both business and social outcomes supports this proposition. This raises a question about how much learning takes place in the partnering firm, because the strategy seems to be to outsource the social or environmental project. Therefore, we label the partnering strategy in scenario 3 “partnering for responsibility outsourcing.”

Lastly, in scenario 1 (low standard adoption/low CSO dominance) stakeholder pressure was not relevant for any of the collaborative behaviors. This indicates that firms in this scenario tended to fly under the radar of stakeholders. They likely collaborated with CSOs to gain more visibility and capture the attention of stakeholders. This interpretation is underpinned by the lack of importance of trust in their CSO partners. Further, interorganizational connectivity only had a significant impact on social performance, and not on business performance. Hence, while these firms wished to understand what CSOs were doing, they did not interfere. They most likely needed this information for communication and public relation purposes. Therefore, we label the partnering strategy in scenario 1 “partnering for visibility.”

These findings reinforce results from other contexts – that stakeholder pressure on its own is insufficient to achieve meaningful and lasting outcomes (cf., Sinkovics et al. 2016). Further, even in an environment where CSOs abound and the government has initiatives in place to facilitate interaction between firms and CSOs, the right match is difficult to achieve. Our four scenarios indicate the existence of four partnering strategies that firms adopt, depending on the degree of competence match between firms and their CSO partners. MNEs wishing to enter South Korea are advised to seek collaboration with CSOs to enhance their legitimacy.

However, the differences across the four scenarios imply that MNEs may need to adjust their partnering strategy depending on the extent of their existing knowledge relevant to the project they seek to establish. Partnering with dominant CSOs seems to produce the highest business and social benefits when both parties have complementary resources and the project is both societally relevant and connected to the firm’s core business. Therefore, MNEs are advised to search for such complementarities to maximize the benefits from the collaboration. However, if MNEs are not able to secure collaboration with dominant CSOs, they are advised to undertake due diligence because less dominant CSOs may struggle with high staff turnover, which can cause disruptions in a project, or they may not possess the right combination of capabilities needed for value co-creation. Therefore, if MNEs cannot secure collaboration with dominant CSOs despite having complementary resources, it may be more beneficial to adopt a “partnering for visibility strategy,” focusing on a project that is in the competence domain of a less dominant CSO and outside the immediate competence domain of the firm. This way, the MNE can gain visibility vis-à-vis stakeholders but is not tempted to take too much control of the project. The MNE may thus focus on building interorganizational connectivity to learn about the issue and utilize the project duration to gauge whether future collaborations and mutual skill upgrading is feasible.

Future research will need to uncover additional factors that contribute to enhancing the social outcomes of business–CSO collaborations. Although interorganizational connectivity and resource sharing seem to have a significant impact on social outcomes, the R2 values derived in this research indicate additional important dimensions that were not part of this study. Future research will also need to control in more detail for the breadth and the depth of collaboration projects (Sinkovics et al. 2021c, 2021d) and examine the micro-foundations of progressing toward value co-creation at the highest level where the project is related to the core business of the firm and simultaneously has a meaningful societal impact (Sinkovics et al. 2015, 2021a). Further, future research is needed to explore details of the dark side of stakeholder pressure (cf., Sinkovics et al. 2016). Government intervention and policy are needed to safeguard against the harmful opportunism of the private sector as well as to guide and incentivize desired behavior (Hamilton 2022; Hofstetter et al. 2021; Sinkovics et al. 2021d). However, interventions are not without unintended consequences, and we need to learn more about how to create safeguards to recognize and remedy such consequences early in the implementation process.

References

Arndt, O., & Sternberg, R. (2000). Do manufacturing firms profit from intraregional innovation linkages? An empirical based answer. European Planning Studies, 8(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/713666423

Bäckstrand, K. (2006). Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. European Environment, 16(5), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.425

Bae, Y., & Kim, S. (2013). Civil society and local activism in south korea’s local democratization. Democratization, 20(2), 260–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2011.650913

Barr, A., Fafchamps, M., & Owens, T. (2005). The governance of non-governmental organizations in uganda. World Development, 33(4), 657–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.09.010

Batchelor, J. H., & Burch, G. F. (2011). Predicting entrepreneurial performance: Can legitimacy help? Small Business Institute Journal, 7(2), 30–45.

Boddewyn, J., & Doh, J. (2011). Global strategy and the collaboration of MNEs, NGOs, and governments for the provisioning of collective goods in emerging markets. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3–4), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.26

Bouncken, R. B., Qiu, Y., Sinkovics, N., & Kürsten, W. (2021). Qualitative research: Extending the range with flexible pattern matching. Review of Managerial Science, 15(2), 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00451-2

Brugmann, J., & Prahalad, C. K. (2007). Cocreating business’s new social compact. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 80–90.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Inkpen, A., Musacchio, A., & Ramaswamy, K. (2014). Governments as owners: State-owned multinational companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(8), 919–942. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.43

Dahan, N. M., Doh, J. P., Oetzel, J., & Yaziji, M. (2010). Corporate-NGO collaboration: Co-creating new business models for developing markets. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.11.003

Den Hond, F., De Bakker, F. G. A., & Doh, J. (2015). What prompts companies to collaboration with NGOs? Recent evidence from the Netherlands. Business and Society, 54(2), 187–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650312439549

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). Wiley.

Doh, J., McGuire, S., & Ozaki, T. (2015). The journal of world business special issue: Global governance and international nonmarket strategies: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.10.002

Doh, J., Rodrigues, S., Saka-Helmhout, A., & Makhija, M. (2017). International business responses to institutional voids. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0074-z

Elkington, J. (1998). Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environmental Quality Management, 8(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/tqem.3310080106

Ferreras-Méndez, J. L., Newell, S., Fernández-Mesa, A., & Alegre, J. (2015). Depth and breadth of external knowledge search and performance: The mediating role of absorptive capacity. Industrial Marketing Management, 47, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.02.038

Fornell, C., & Cha, J. (1994). Partial least squares. In R. P. Bagozzi (Ed.), Advanced methods of marketing research (pp. 52–78). Blackwell.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Gudergan, S. P., Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2008). Confirmatory tetrad analysis in PLS path modeling. Journal of Business Research, 61(12), 1238–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.012

Hahn, R., & Gold, S. (2014). Resources and governance in “base of the pyramid”-partnerships: Assessing collaborations between businesses and non-business actors. Journal of Business Research, 67(7), 1321–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.09.002

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. J. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.016

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Hair, J. F. J., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2018). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage Publications.

Hale, T. N., & Mauzerall, D. L. (2004). Thinking globally and acting locally: Can the johannesburg partnerships coordinate action on sustainable development? The Journal of Environment & Development, 13(3), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496504268699

Hamilton, S. G. (2022). Public procurement – price-taker or market-shaper? Critical Perspectives on International Business, 18(4), 576–615. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-08-2020-0116

Hansen, E. G., & Spitzeck, H. (2011). Measuring the impacts of NGO partnerships: The corporate and societal benefits of community involvement. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 11(4), 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701111159253

Harangozó, G., & Zilahy, G. (2015). Cooperation between business and non-governmental organizations to promote sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 89, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.092

Heckman, R., & Guskey, A. (1998). The relationship between alumni and university: Toward a theory of discretionary collaborative behavior. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 6(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.1998.11501799

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Hofstetter, J. S., De Marchi, V., Sarkis, J., Govindan, K., Klassen, R., Ometto, A. R., et al. (2021). From sustainable global value chains to circular economy—different silos, different perspectives, but many opportunities to build bridges. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 1(1), 21–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00015-2

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Hult, G. T. M., Hair, J. F., Proksch, D., Sarstedt, M., Pinkwart, A., & Ringle, C. M. (2018). Addressing endogeneity in international marketing applications of partial least squares structural equation modeling. Journal of International Marketing, 26(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.17.0151

Jamali, D., Yianni, M., & Abdallah, H. (2011). Strategic partnerships, social capital and innovation: Accounting for social alliance innovation. Business Ethics: A European Review, 20(4), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2011.01621.x

Janney, J. J., Dess, G., & Forlani, V. (2009). Glass houses? Market reactions to firms joining the un global compact. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0052-x

Jiang, X., Jiang, F., Cai, X., & Liu, H. (2015). How does trust affect alliance performance? The mediating role of resource sharing. Industrial Marketing Management, 45, 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.02.011

Kim, C. H., Amaeshi, K., Harris, S., & Suh, C.-J. (2013). CSR and the national institutional context: The case of South Korea. Journal of Business Research, 66(12), 2581–2591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.05.015

Kobrin, S. J. (2015). Is a global nonmarket strategy possible? Economic integration in a multipolar world order. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.10.003

Lam, A. (1997). Embedded firms, embedded knowledge: Problems of collaboration and knowledge transfer in global cooperative ventures. Organization Studies, 18(6), 973–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069701800604

Linton, A. (2005). Partnering for sustainability: Business–NGO alliances in the coffee industry. Development in Practice, 15(3–4), 600–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520500075664

Liu, C.-L.E., Sinkovics, N., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2020). Achieving relational governance effectiveness: An examination of B2B management practices in Taiwan. Industrial Marketing Management, 90, 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.08.004

Lucea, R., & Doh, J. (2012). International strategy for the nonmarket context: Stakeholders, issues, networks, and geography. Business and Politics, 14(3), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1515/bap-2012-0018

Lui, S. S., & Ngo, H.-Y. (2004). The role of trust and contractual safeguards on cooperation in non-equity alliances. Journal of Management, 30(4), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.02.002

Mars, M. M., & Lounsbury, M. (2009). Raging against or with the private marketplace?: Logic hybridity and eco-entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Inquiry, 18(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492608328234

Mellahi, K., Frynas, J. G., Sun, P., & Siegel, D. (2016). A review of the nonmarket strategy literature: Toward a multi-theoretical integration. Journal of Management, 42(1), 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617241

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

Office, N. S. (2015). No. of Korean SMEs & employees by year. https://www.mss.go.kr/site/eng/02/10204000000002016111504.jsp. Accessed 21 Apr 2020

Pagell, M., Wu, Z., & Wasserman, M. E. (2010). Thinking differently about purchasing portfolios: An assessment of sustainable sourcing. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 46(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2009.03186.x

Park, S., & Gupta, S. (2012). Handling endogenous regressors by joint estimation using copulas. Marketing Science, 31(4), 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1120.0718

Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2008). The decision to persist with underperforming alliances: The role of trust and control. Journal of Management Studies, 45(7), 1217–1243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00791.x

Plante, C. S., & Bendell, J. (1998). The art of collaboration: Lessons from emerging environmental business–NGO partnerships in Asia. Greener Management International: The Journal of Corporate Environmental Strategy and Practice, 24(4), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.978-1-907643-14-9_15

Pratt Miles, J. (2013). Designing collaborative processes for adaptive management: Four structures for multistakeholder collaboration. Ecology and Society, 18(4), 5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05709-180405

Prno, J., & Slocombe, D. S. (2012). Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resources Policy, 37(3), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002

Quélin, B. V., Kivleniece, I., & Lazzarini, S. (2017). Public-private collaboration, hybridity and social value: Towards new theoretical perspectives. Journal of Management Studies, 54(6), 763–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12274

Richter, N. F., Cepeda, G., Roldán, J. L., & Ringle, C. M. (2016a). European management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Management Journal, 34(6), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.08.001

Richter, N. F., Sinkovics, R. R., Ringle, C. M., & Schlägel, C. (2016b). A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 376–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-04-2014-0148

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). Smartpls 3. SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com

Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

Rivera-Santos, M., & Rufín, C. (2010). Odd couples: Understanding the governance of firm–NGO alliances. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0779-z

Rondinelli, D. A., & London, T. (2003). How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: Assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations. Academy of Management Perspectives, 17(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2003.9474812

Rönkkö, M., & Ylitalo, J. (2011). PLS marker variable approach to diagnosing and controlling for method variance. International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS) Proceedings, 8

Sakarya, S., Bodur, M., Yildirim-Öktem, Ö., & Selekler-Göksen, N. (2012). Social alliances: Business and social enterprise collaboration for social transformation. Journal of Business Research, 65(12), 1710–1720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.012

Seitanidi, M. M., & Crane, A. (2009). Implementing CSR through partnerships: Understanding the selection, design and institutionalisation of nonprofit-business partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9743-y

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31(6), 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279601

Shah, S. K., & Corley, K. G. (2006). Building better theory by bridging the quantitative–qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1821–1835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00662.x

Shumate, M., & O’Connor, A. (2010). The symbiotic sustainability model: Conceptualizing ngo–corporate alliance communication. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 577–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01498.x

Sinkovics, N. (2016). Enhancing the foundations for theorising through bibliometric mapping. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1108/imr-10-2014-0341

Sinkovics, N. (2018). Pattern matching in qualitative analysis. In C. Cassell, A. Cunliffe, & G. Grandy (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (pp. 468–485). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430236.n28

Sinkovics, N., Sinkovics, R. R., & Yamin, M. (2014). The role of social value creation in business model formulation at the bottom of the pyramid – implications for MNEs? International Business Review, 23(4), 692–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.12.004

Sinkovics, N., Sinkovics, R. R., Hoque, S. F., & Czaban, L. (2015). A reconceptualisation of social value creation as social constraint alleviation. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 11(3/4), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-06-2014-0036

Sinkovics, N., Hoque, S. F., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2016). Rana Plaza collapse aftermath: Are CSR compliance and auditing pressures effective? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 29(4), 617–649. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-07-2015-2141

Sinkovics, N., Choksy, U. S., Sinkovics, R. R., & Mudambi, R. (2019). Knowledge connectivity in an adverse context: Global value chains and Pakistani offshore service providers. Management International Review, 59(1), 131–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-018-0372-0

Sinkovics, N., Gunaratne, D., Sinkovics, R. R., & Molina-Castillo, F.-J. (2021a). Sustainable business model innovation: An umbrella review. Sustainability, 13(13), 7266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137266

Sinkovics, N., Liu, C.-L., Sinkovics, R. R., & Mudambi, R. (2021b). The dark side of trust in global value chains: Taiwan’s electronics and it hardware industries. Journal of World Business, 56(4), 101195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101195

Sinkovics, N., Sinkovics, R. R., & Archie-Acheampong, J. (2021c). The business responsibility matrix: A diagnostic tool to aid the design of better interventions for achieving the SDGs. Multinational Business Review, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/mbr-07-2020-0154

Sinkovics, N., Sinkovics, R. R., & Archie-Acheampong, J. (2021d). Small- and medium-sized enterprises and sustainable development: In the shadows of large lead firms in global value chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 4(1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00089-z

Steckel, R., & Simons, R. (1992). Doing best by doing good: How to use public purpose partnerships to boost corporate profits and benefit your community. EP Dutton

Sun, P., Doh, J. P., Rajwani, T., & Siegel, D. (2021). Navigating cross-border institutional complexity: A review and assessment of multinational nonmarket strategy research. Journal of International Business Studies. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00438-x

Teegen, H., Doh, J. P., & Vachani, S. (2004). The importance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in global governance and value creation: An international business research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(6), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400112

Tripsas, M., Schrader, S., & Sobrero, M. (1995). Discouraging opportunistic behavior in collaborative r & d: A new role for government. Research Policy, 24(3), 367–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(93)00771-K

Trochim, W. M. K. (1989). Outcome pattern-matching and program theory. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(4), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90052-9

UN (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembley 70 session. Retrieved 12 December, 2021, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

Van Huijstee, M., & Glasbergen, P. (2008). The practice of stakeholder dialogue between multinationals and NGOs. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(5), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.171

Van Huijstee, M., & Glasbergen, Pi. (2010). Business–NGO interactions in a multi-stakeholder context. Business and Society Review, 115(3), 249–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8594.2010.00364.x

Weber, C., Weidner, K., Kroeger, A., & Wallace, J. (2017). Social value creation in inter-organizational collaborations in the not-for-profit sector – give and take from a dyadic perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 54(6), 929–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12272

Wible, J. R., & Sedgley, N. H. I. (1999). The role of econometrics in the neoclassical research program. In R. F. Garnett (Ed.), What do economists know? : New economics of knowledge (pp. 169–190). Routledge

Wilburn, K., & Wilburn, R. (2011). Achieving social license to operate using stakeholder theory. Journal of International Business Ethics, 4(2), 3–16.

Willis, C. N. (2020). Democratization and civil society development through the perspectives of gramsci and tocqueville in South Korea and Japan. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 5(4), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891119867401

Wyrwa, J. (2018). Cross-sector partnership as a determinant of development – the perspective of public management. Management, 22(1), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.2478/manment-2018-0009

Zaheer, A., McEvily, B., & Perrone, V. (1998). Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organization Science, 9(2), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.2.141

Zeng, N., Liu, Y., Gong, P., Hertogh, M., & König, M. (2021). Do right PLS and do PLS right: A critical review of the application of PLS-SEM in construction management research. Frontiers of Engineering Management, 8(3), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42524-021-0153-5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Appendix Fig. 5

See Appendix Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sinkovics, N., Kim, J. & Sinkovics, R.R. Business-Civil Society Collaborations in South Korea: A Multi-Stage Pattern Matching Study. Manag Int Rev 62, 471–516 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00476-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00476-z