Abstract

This study explores accelerated internationalization among inexperienced digital entrepreneurs who lack resources such as prior experience, knowledge, and networks, which previous research regards as prerequisites for such growth. Following an in-depth qualitative research methodology, the findings reveal three theoretical mechanisms through which inexperienced entrepreneurs can make international commitment decisions with regard to the internationalization of their digital firms. The first is a novel mindset-based approach through which an entrepreneur can make an affective commitment to the international stakeholders within a digital community. Entrepreneurs do that by applying pull-based tools in digital communication to build interest among potential network contacts. The second mechanism is a means-based approach following effectuation logic resulting in an effectual form of commitment to international stakeholders in the digital community. The mechanism relies on applying push-based tools for digital communication to facilitate interactions with known network contacts. The third mechanism is continuance commitment to international business that entrepreneurs can foster over time in tandem with accumulated international experiential knowledge. This research provides an entrepreneurial decision-making model that extends effectuation theory and integrates it with extant research. The resulting holistic entrepreneurial decision-making model explains the accelerated internationalization of digital firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Digital technologies enable entrepreneurial activity that incorporates novel technology and creates new business ventures. Consequently, there has recently been additional room for accelerated internationalization, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic (see e.g., Fraccastoro et al., 2021a). The current research perspective is that digitalization is changing entrepreneurs’ decision-making processes and outcomes such that they are becoming more fluid and feature goals that are less predefined than previously (Nambisan, 2017). Jiang and Tornikoski (2019) reported that inexperienced entrepreneurs face several forms of uncertainty, which they neither fully comprehend nor know how to address. Interestingly, the number of firms in several industries successfully achieving accelerated internationalization, despite their entrepreneurs being inexperienced, seems to be growing (Luostarinen & Gabrielsson, 2006; Rosenberg, 2018). The common feature of many of these entrepreneurs seems to be that they run digital ventures that successfully leverage networks (Bell & Loane, 2010). This study aims to extend extant research by investigating entrepreneurs’ decision-making in connection to the networking of digital firms during accelerated internationalization.

Prior research proposes that entrepreneurial decision-making logics, such as effectuation, can facilitate networking and mitigate the resource shortfall that can hinder young and inexperienced firms (e.g., Dew et al., 2011; Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019; Sarasvathy, 2001). A complementary perspective stems from an emerging digital entrepreneurship stream of research suggesting that different elements of digitalization – such as artifacts (e.g., mobile apps), platforms (e.g., Apple Appstore), and infrastructure (e.g., social media) – facilitate the decision-making and networking of entrepreneurs to potentially enable accelerated internationalization.

The empirical part of this study explores a globally renowned and successful digital entertainment company, to which we assign the pseudonym Alpha. Alpha has expanded from being a mobile-game developer to creating movies and being at the center of an extensive franchising business. The firm started as a university project and became a global industry leader in less than 15 years. The firm has faced many key events and made some great decisions throughout its existence despite its entrepreneurs having almost no prior international business experience or networks at the outset. Alpha’s success runs counter to the conventional wisdom on international business that holds entrepreneurs’ international experiential knowledge determines venture creation, growth, and foreign expansion (Eriksson et al., 1997; Kessler & Frank, 2009; Politis, 2005). Effectuation theory (Sarasvathy, 2001) does not explain accelerated internationalization by inexperienced entrepreneurs running digital ventures; albeit the extension of the theory to interpret networking behavior is beneficial (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019). The digital entrepreneurship stream of research has not addressed exceptional internationalization behavior either (Nambisan, 2017), although digitalization does have an intuitive appeal to explain this exceptional behavior.

Based on an extensive literature review of these two streams, we note a research gap around examining entrepreneurs’ decision-making in connection to networking within the digital community during accelerated internationalization. The current research also addresses the calls for studies focusing on digital entrepreneurs involved in accelerated internationalization, covering the entire firm lifecycle from birth to maturity (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Coviello, 2015). Consequently, this study focuses on the following research question: How do entrepreneurs’ decision-making logic and networking within the digital community interact over the course of accelerated internationalization?

The methodological approach selected in the current study responds to calls in recent international business research suggesting that the available qualitative research could benefit from greater methodological transparency (e.g., Ji et al., 2018). Instead of the currently popular positivistic approach, we are guided by the philosophy of social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, 1967; Burr, 1995; Ritchie et al., 2013), the ontological assumption of subjectivism, and the subjective epistemological assumption (Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2015), associated with the data of specific descriptions (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Ritchie et al., 2013), such as discourses, understood as comprising meaning frames (Edwards, 1997; Hall, 1997). Birkinshaw et al. (2011) suggested that the use of interpretative qualitative methods and techniques can provide a comprehensive understanding of different processes in international business research. When researchers open organizational processes with questions based on how, who, and why, qualitative methods can reveal individual and collective actions as they unfold over time (Doz, 2011).

We contribute to the earlier international entrepreneurship literature by extending the research on entrepreneurial decision-making into the digital networking context. More specifically, we frame our investigation with the literature of effectuation and digital entrepreneurship and also clarify the roles of a global mindset, entrepreneurial means, commitment, and learning and knowledge in the internationalization of inexperienced digital firms.

Accordingly, we propose a revised entrepreneurial decision-making model, advocating three decision-making alternatives applied by entrepreneurs to increase commitment within the digital community. The value of that contribution (see Corley & Gioia, 2011) lies in the new entrepreneurial decision-making model presented explaining accelerated internationalization. That explanation also makes a major contribution to international entrepreneurship research by unveiling entrepreneurial decision-making in the context of accelerated internationalization (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994; Prashantham et al., 2019; Sarasvathy, 2001). The explanation is particularly apposite regarding networking within the digital community. Furthermore, our model acknowledges the role of new digital environment and the emergence of digital entrepreneurship in accelerating internationalization, which has largely been ignored and may partly explain this behavior (Nambisan, 2017). Finally, the proposed framework contributes to research examining the maturing of firms undertaking accelerated internationalization (see also, Gabrielsson et al., 2014).

2 Theoretical Review

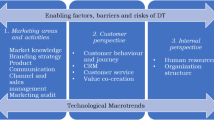

Our conceptual foundation is based on a systematic literature search of the most relevant journals related to studies investigating effectuation, networking, and digital entrepreneurship. We used Reuter’s Web of Science database and EBSCOhost (multiple databases) to perform an advanced search within relevant journals publishing international entrepreneurship research, such as Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Business Venturing, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of World Business, Management International Review, and Small Business Economics. We considered articles published up until 2021. We searched for the keywords internationalization, accelerated internationalization, effectuation, commitment, and digital entrepreneurship appearing anywhere in the text (including the title, abstract, keywords, and main text). Interestingly, the literature reviewed revealed that there is one stream of research under label entrepreneurs’ decision-making logic that covers research dealing with use of effectuation logic and networking. Moreover, there is another stream of research that can be labeled as digital entrepreneurship, which provides insights into how entrepreneurial firms can internationalize within the digital community. However, there is no mention in the literature about how entrepreneurial decision-making logic and related networking applies to digital entrepreneurship in the context of accelerated internationalization. The following sections review earlier research and draw conclusions based on those studies; we present our positioning against the identified key articles in Table 1.

2.1 Entrepreneurial Decision-Making

Earlier research suggests that international experiential knowledge exerts a key influence on accelerated internationalization, such that prior knowledge of foreign markets can enhance the speed with which an entrepreneurial team perceives opportunities (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005; Reuber & Fischer, 1997). Entrepreneurs are always at the heart of decisions and are also the key individuals from a learning perspective. Penrose (1966) asserted.

Experiential knowledge can only be learned through personal experience. With experiential knowledge, emphasis is placed on the change in the services the human resources can supply which arises from their activity… experience itself can never be transmitted, it produces a change – frequently a subtle change – in individuals and cannot be separated from them (p. 53).

The balance between entrepreneurial resources (e.g., international experiential knowledge) and international market conditions (e.g., market turbulence and position in a network) can cause uncertainty for entrepreneurial firms expanding internationally relatively soon after their foundation (see, e.g., Magnani & Zucchella, 2019). While more information can address uncertainty (Luce & Raiffa, 1957), decision-makers never have full access to all available information (Kirzner, 1973). Hence, they are cognitively limited and likely to fail to solve highly complex problems in an objectively rational way (Williamson, 1981). Effectuation theory is useful in unpredictable situations, such as new business environments where decision-makers have opportunities to shape a future in which forecasting is difficult or even inconceivable (Gabrielsson & Gabrielsson, 2013; Jiang & Tornikoski, 2019; Sarasvathy, 2001).

The effectuation process differs from the traditional planning-based approach, which Sarasvathy et al. (2014) refer to as causation. An effectual entrepreneur focuses on the means available and determines what can be done (Sarasvathy et al., 2014). The entrepreneur’s background, identity, knowledge, and active networks trigger the adoption of an effectuation logic, which is then reflected in her/his decision-making process and actual behaviour. Sarasvathy (2008) proposed three questions to capture the process: Who I am? What I know? Whom I know? The answers to these three questions present the entrepreneur with the available means which are the starting point for the effectual process. For instance, entrepreneurs ask themselves, “What can I do?” and then engages with the stakeholders, resulting in their making effectual commitments to stakeholders. An effectual commitment is a means-oriented commitment with other stakeholders within the network which the entrepreneur makes in exchange for a voice in shaping some focal market they seek for their own benefit (Van Mumford & Zettinig, 2022). In addition, Sarasvathy’s effectuation theory describes the effectual entrepreneur adopting an affordable loss approach rather than one focusing on expected returns. This trial-and-error process allows the entrepreneur to experiment with potential business opportunities without risking bankruptcy (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008).

Furthermore, effectual entrepreneurs must find committed partnerships that provide mutual benefits and new opportunities (Sarasvathy, 2001). Sarasvathy (2001) maintained that entrepreneurs who follow an effectual approach turn unexpected events into profitable opportunities that can lead to unexpected outcomes (Fisher, 2012). Rather than trying to analyze opportunities and avoid risks, effectual entrepreneurs control their future by focusing on shaping it through their own actions (Sarasvathy, 2008; Sarasvathy et al., 2014).

Some scholars have suggested that a global entrepreneurial mindset (“orientation to the world that shapes the behavior of the individual”, Rhinesmith, 1992, p. 63) and an immediate commitment decision are prerequisites of successful accelerated internationalization (Gabrielsson et al., 2008; Magnani & Zucchella, 2019; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). In that case, the commitment precludes an experiential knowledge prerequisite and is affective. Affective commitment is triggered by another party identifying with the global perspectives of the entrepreneurs and the opportunities they discover or create during the internationalization process (Gabrielsson et al., 2008; Meyer & Allen, 1991).

Over time, new goals emerge from actions that can be pursued if resources are acquired. Having acquired new resources (e.g., international experiential knowledge, funding, or networks), entrepreneurs may amend their perceptions of their firm’s mission, vision, or strategy. The effectuation process may also become one based more on causal decision-making. In causation, the entrepreneur focuses on the target, which involves asking what should be done using underutilized network relationships and with partners that could confer benefits (Engel et al., 2017; Vissa & Bhagavatula, 2012). Causal decision-making typically requires experiential knowledge of market opportunities and associated problems. Having that knowledge can facilitate commitment decisions involving a fear of loss into the international digital market and its networks, best described as continuance commitments (Gabrielsson et al., 2008; Meyer & Allen, 1991). When a venture has acquired sufficient experiential knowledge of operating in a foreign market, it might consider new market-specific investments.

Effectuation theory has been advancing in huge leaps in conjunction with networking. Galkina and Chetty (2015) established that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) utilize effectuation rather than causation to tackle the uncertainty of internationalization. The effectuation approach permits effectual commitments to network relationships, boosts the means available to their ventures and creates new opportunities. Coviello (2006), however, illustrated that intensifying international commitment through stronger and more strategically compatible international customer relationships may demand more planned networking (i.e., causation), and that a causally increased customer base and extended networks are likely to increase international revenues and learning in the case of an SME (Prashantham et al., 2019). Interestingly, Kerr and Coviello (2020) reconceptualized effectuation theory as a multilevel phenomenon that drives networking. The same research presented a model of how individual-level use of effectuation connects with dyadic interactions between people and mutual commitment, which ultimately explain entrepreneurial network dynamics. At this level, effectuation theory turns into an assessment of shared means and addresses the question “What can we do?” The answer can trigger changes to the structural and relational elements of a network.

Previous research suggests that entrepreneurial teams have an exceptional capacity for learning, which facilitates accelerated internationalization (Reuber & Fischer, 1997; Shrader et al., 2000). The age of a firm and the extent to which it is a knowledge intensive type are important for learning and rapid international growth (Autio et al., 2000; Puthusserry et al., 2020). Accordingly, young, knowledge-intensive firms enjoy the learning advantages of newness, which facilitate their learning about international expansion and help them avoid the barriers that impede learning among older firms. However, the assertion that new ventures benefit from moving immediately into international markets is controversial and does not seem to offer a satisfactory explanation of accelerated internationalization (Zhou & Wu, 2014).

Their ability to learn from partnerships can partially explain the accelerated internationalization of inexperienced firms (Mansoori & Lackéus, 2019; Read et al., 2016). Recently, Puthusserry et al. (2020) reported that SMEs utilize both internal and external sources of knowledge and apply various learning approaches, such as self-learning, trial-and-error, and experience during post-entry growth. Causation is particularly associated with information-based strategic responses (Van Werven et al., 2015; Vissa & Bhagavatula, 2012; Wiltbank et al., 2006, 2009), whereas effectuation is defined as a logic of entrepreneurial expertise that is dynamic and interactive – it creates new market opportunities and consists of two parallel cycles of acquiring new means and setting new goals (Fisher, 2012; Sarasvathy, 2008).

2.2 Digital Entrepreneurship

Digital entrepreneurship refers to new venture creation and the transformation of existing businesses through the development of new digital technologies and/or the novel application of such technologies (European Commission, 2015). A prominent researcher in this field, Nambisan (2017), argues that digital technologies (e.g., mobile computing, data analytics, social media, cloud computing, blockchain encryption, or crowdfunding) shape entrepreneurial processes and outcomes to make them less bounded and predefined. Therefore, the question of interest is whether digital entrepreneurship provides tools that help understand accelerated internationalization by inexperienced entrepreneurs in today’s digitalized economy, which is more dynamic and uncertain than ever before.

Digital entrepreneurship research lies at the intersection of entrepreneurship and digital technologies and addresses the implications of digitalization on entrepreneurial processes and outcomes (Nambisan, 2017). Digital entrepreneurship is enabled by three distinct but related elements of digital technology that might facilitate internationalization; digital artifacts, platforms, and infrastructures (Nambisan, 2017; Nzembayie et al., 2019). Digital artifacts are defined as applications or digital or media components that are part of new products or services and provide end-users with a particular functionality or value (Kallinikos et al., 2013; Nambisan, 2017; Nzembayie et al., 2019). For example, mobile apps, software, and media content are inherently borderless digital artifacts. Digital platforms are shared common sets of services and architectures that host complementary offerings, including digital artifacts (Elia et al., 2020; Nambisan, 2017; Parker et al., 2016). Digital marketplaces, such as Apple’s Appstore and the Google Play Store, are examples of digital platforms that provide instant international distribution channels for firms using those platforms as a complementor. Digital infrastructures are digital technology tools and systems that provide communication, collaboration, and/or computing capabilities to support digital entrepreneurship (Nambisan, 2017; Nzembayie et al., 2019). Cloud computing, social media, and data analytics are examples of digital infrastructures that facilitate international communication and collaboration.

Digital technologies can be an outcome of entrepreneurial processes but also of the environment (or context) where those processes are conducted (Elia et al., 2020). Accordingly, digital technologies connect entrepreneurial actors and provide a new environment for the entrepreneurial process and the emergence of digital communities, which together can form digital entrepreneurship ecosystems (Sahut et al., 2019). Ghezzi and Cavallo (2020) recently showed that digital startups in highly dynamic and unpredictable environments tend to commit to an ecosystem or network of partnerships to enhance their position and transfer value to their customers. Marketing communication incorporates two approaches: “push is targeted outbound communication originating from the marketer, while the pull is inbound communication that is initiated by the end-customer” (Unni & Harmon, 2007, p. 30). However, often this pull from end-customers has been created by more general type of marketing activities of the marketer. These, concepts may be important as earlier research examining the location specificity of social media communication has suggested that communication often is more general in the early phase of internationalization and becomes more targeted as the internationalization advances (Fraccastoro et al., 2021b). However, research on the role of digital technologies – such as digital artifacts, platforms, infrastructures, and the resulting digital entrepreneurship ecosystems – in enabling accelerated internationalization remains in its infancy.

3 Methodology

The study required a research philosophy and methods that offered the opportunity to explore and understand the entrepreneurs’ decision-making logics, networking, and digital entrepreneurship in one accelerated internationalizing SME in a modern, technology-oriented industry. The study applied the philosophy of social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, 1967; Burr, 1995; Ritchie et al., 2013), the ontological assumption of subjectivism, and the subjective epistemological assumption (Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2015, pp. 15–16) associated with the data of specific descriptions (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Ritchie et al., 2013), as presented in Table 2. These philosophical and methodological decisions produced unique insights into the complex phenomena of decision-making and networking among digital entrepreneurs involved in accelerated internationalization and the associated changes over time.

3.1 Empirical Context and Data Collection

The entrepreneurial behavior is studied within the context of a digital-based SME, here assigned the pseudonym Alpha. Alpha has undertaken accelerated internationalization and was selected as a case study because it operates in the game development industry – a highly technology-oriented field. In addition the internationalization was driven by inexperienced entrepreneurs.

Three university students keen to develop games founded Alpha in 2003. The students had won a game development contest that summer, which attracted the attention of established firms in the games development industry, leading to the creation of Alpha. Within three years, Alpha was drawing 25% of its total sales revenue from Europe, 50% from the United States, and 25% from Asia (including China, Korea, and Japan).

We conducted eight interviews applying the ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions of our study. The interviewees had been central to Alpha’s development and included the firm’s founders, chief executive officers (CEOs), a chief technical officer (CTO), and a chief marketing officer (CMO) (see Table 2). Additionally, a game industry expert was interviewed to provide an objective view of the industry and an external perspective on Alpha’s success. This interview was also used to confirm the data gathered from interviews with Alpha staff. Before engaging in the primary interviews, we invited two informants to participate in pilot interviews to refine the planned questions. All key informants were assigned pseudonyms to protect their identities.

We asked the participants to describe the entrepreneurs’ decision-making and networking associated with Alpha, from its founding to the present, focusing on the firm’s internationalization process and its development and maintenance. Each interview began with background questions before the interviewees were invited to provide an open-ended, chronological account of Alpha’s internationalization. We encouraged the key informants to describe their subjective perspectives (Haytko, 2004; Ritchie et al., 2013) regarding changes and key events. The research team sought to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the interviewees’ experiences and how they organized them (Polkinghorne, 1995). Previous research has established that influential and knowledgeable informants are the most reliable sources of information, particularly if they can recall important real-time events (Huber & Power, 1985; Kumar et al., 1993). The research team asked questions designed to acquire a holistic and detailed understanding of the phenomenon in question (Graebner, 2009; Lipton, 1977). Examples of the interview questions include: What was your vision in the beginning? How would you describe the different events of the internationalization process? How would you describe the entrepreneur’s decision-making process with respect to internationalization? And please describe the associated digital and non-digital networking of the entrepreneurs during this process.

This study used multiple data sources to avoid subject bias (Jick, 1979) and also gathered secondary data relating to Alpha’s lifecycle. A search of the firm’s websites, business publications, and annual reports resulted in the identification of 38 links related to the firm’s early history (2003–2009), 22 links related to the success of the Alpha brand (2009–2021), 28 links related to Alpha’s collaboration with global consumer brands (2014–2016), and 17 links related to the creation of a movie version of an Alpha game (2016–2017). The secondary data complemented the primary data, confirming Alpha’s key events and providing context for the interviews, including the changes in Alpha’s internationalization process over time. Having gathered the data, we used triangulation to ensure the validity of the interviews, cross-checked the primary interview data for consistency, and, when appropriate, compared them with the secondary data (Lupina-Wegener et al., 2015). The interviewees were contacted by telephone if clarification was required, a step calculated to increase the reliability and validity of the datasets by enhancing trustworthiness and credibility (Schwandt, 2001). Each interview was recorded and the transcripts sent to the interviewees for verification. There were no significant discrepancies that could not be explained by the iterative nature of the data collection. Table 3 describes the empirical interview data and the secondary data in detail.

3.2 Discourse Analysis

The deep, rich dataset encouraged us to find an appropriate method to explore the decision-making logic and digital entrepreneurship of the entrepreneurs at the heart of a digital accelerated internationalized SME. Therefore, we decided to focus on investigating the meanings (Riessman, 1993) embedded in the discourses of key informants from Alpha describing the firm’s internationalization process (Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2015; Hall, 1997). Because people describe how they think about a topic, event, or experience through discourse, this method allowed us to analyze the changes in meaning structures over time and, thus, to understand the interviewees’ decision-making processes and digital entrepreneurship during the firm’s internationalization process. One advantage of this approach is that the meanings found in informants’ discourses always follow the logic of their way of organizing and understanding real-life events and environments (Riessman, 1993).

Two researchers conducted the initial data analysis and carefully reviewed the data together to identify the key events in Alpha’s history; this process aligned with the recommendations of Lupina-Wegener et al. (2015). Next, each researcher continued their analysis individually to obtain a comprehensive overview of the key events. They explored the meanings by focusing on each key event and allowing changes in meaning to emerge inductively. Conducting two separate analyses and using the secondary data to support and strengthen the primary data helped the researchers interpret the key informants’ independent and shared meaning systems, which are socially constructed and understood as subjective (Burr, 1995; Haytko, 2004; Ritchie et al., 2013). In parallel with the meaning analysis, the researchers abductively discussed the relevant literature and their empirical interpretations to corroborate the most relevant insights (Kanitz et al., 2021).

Finally, the researchers compared their interpretations of the meanings and discussed any differences, resolving instances of disagreement through further discussion and data analysis, as suggested by Jick (1979). When they had developed a shared understanding, the researchers built the discourses together based on the meanings and followed a timeline of key events.

4 Findings

Exploring the interaction between entrepreneurs’ decision-making logic and networking within the digital community during Alpha’s accelerated internationalization revealed two discourses: the discourse of international experiential knowledge and decision-making logic and the discourse of international commitment to digital communities. Both discourses were identified in the entrepreneurs’ descriptions of the meanings that changed over time. Specifically, the discourses illustrated a path to overcoming a lack of international experimental knowledge, showed an evolution of decision-making logic, and recognized the commitment to international digital communities during Alpha’s accelerated internationalization. Table 4 summarizes the key events in Alpha’s history and the discourses in meanings that revealed the firm’s path to internationalization. Representative interview excerpts are presented to clarify the findings on each key event.

Below we have also summarized Alpha’s accelerated internationalization discourses to provide telling insights into the phenomena explored.

4.1 From the Assembly Game Development Contest to Collaboration with Beta

The Alpha founders were university students whose lack of international experiential knowledge was compensated for by their favoring an effectuation approach. They had a dream of becoming global, well-respected talents in digital programming (who I am). Because of their self-learned skills as amateur talents in mobile-game development, they believed in themselves and wanted to show their competence (what I know). However, regarding their international experiential knowledge, the entrepreneurs lacked the resources, dense social networks, and previous international management and industry expertise to facilitate the process of establishing a new venture with an international orientation.

In 2003, their success at Assembly, an influential game development contest, inspired them to develop more games and drew increased interest from important network contacts. In particular, the advice and support of industry experts attending the Assembly event reinforced the entrepreneurs’ belief in their digital abilities as game developers. Furthermore, success in this initial game contest provided a foundation for what our data indicate entrepreneurs should initially ask themselves: How can I interest others? The entrepreneurs joined crucial digital networks for game publishers, contacted international customers, participated in digital fairs, and contributed to digital communities (e.g., initial internet-based mobile-game actors and LinkedIn). By these means, they attracted more interest, creating a pull factor in digital networks. As a result, the young entrepreneurs were recognized as new digital talents among game developers in the mobile gaming industry network, which encouraged them to establish a new venture.

Although the entrepreneurs lacked international experiential knowledge, their capabilities in mobile-game development and digital communication (e.g., internet-based communication via email, blogs, forums, and chats) facilitated access to Beta, a multinational corporation (MNC) digital games publisher, in 2004. Because Beta management had identified the entrepreneurs behind Alpha as potential partners, the young entrepreneurs made an effectual commitment to the MNC game developer (new means) and instigated close collaboration with them. This effectual commitment included an investment from the Alpha side into research and development work in order to meet Beta’s expectations. The collaboration set the Alpha entrepreneurs up with a new insider position and provided access to the global digital community, which spurred the firm’s accelerated internationalization. The Alpha staff described their relationship with Beta as active and beneficial, and Beta invested considerable resources into the partnership and, thus, shared the risk of the new venture. Although Beta gave Alpha significant autonomy in the collaboration, the Alpha entrepreneurs recognized the need to become more independent in their digital entrepreneurship.

4.2 From Rebranding as Alpha Ltd. to the Launching of the Alpha Mobile Game

The Alpha entrepreneurs’ initial international experiential knowledge combined with the danger of overdependence and enhanced digital capability (as new means) in mobile-game development was the foundation of their self-efficacy. The perspective led to them adopting an effectual approach as a decision-making logic. Such entrepreneurial behavior enabled increasingly greater effectual commitment in global game development collaborations with several multinational corporations, and they felt able to bypass Beta, their MNC distributor. Alpha’s management created a push through digital communication (e.g., LinkedIn and other digital channels) by interacting with key players in the digital community – an example of employing effectual logic. Subsequently, the Alpha entrepreneurs committed to subcontract arrangements with several direct MNC customers in the digital mobile-game industry, which led them to invest the money received from an angel investor into rebranding the firm as Alpha Ltd. Such collaborations particularly helped the Alpha entrepreneurs recognize that they needed to gain brand visibility among consumers of the digital community (as new goals). To reduce the firm’s dependence on any single relationship and to pursue rapid international growth, Alpha sold its own mobile games to operators, which triggered a staff expansion in 2006.

Owing to the entrepreneurs’ very limited experience of building a profitable business partnership, the expansion was unsuccessful. The entrepreneurs almost lost their financial independence and the firm failed to realize its international sales forecasts. However, Alpha’s entrepreneurs learned more about the game development industry and used that knowledge to develop new and better games. The entrepreneurs’ digital capability, which now included analytical skills and a specific understanding of the global mobile-game industry, prompted the move toward a causation-based strategic decision to commercialize their first mobile game (a digital artifact). The game deliberately targeted consumers globally and, in time, proved an enormous success. The innovative touch-screen technology exposed the game to new consumers in the digital mobile-game industry and was enabled by the emerging digital global marketplaces or digital platforms.

Alpha now had international experiential knowledge of how the digital mobile-game industry worked and what attracted the digital community. They used that knowledge and applied a causation decision-making logic during the development process of their new mobile game. The entrepreneurs understood that reaching the firm’s end customers relied on leveraging the marketing resources and digital platforms available to large multinational companies. Accordingly, Alpha adopted a causation-based process, seeking network partners with strong relationships with Apple and Google. As a result, a UK-based agency introduced them to Apple UK, which led to Alpha products being prominently displayed in Apple’s marketplace listings, first in the UK and then globally. In 2009, the entrepreneurs’ continuance commitment to the Alpha brand and mobile-game development led to Alpha’s innovative mobile game being marketed as a breakthrough product in the App Store and Android Market. The game changed the way mobile games were played. In the global mobile game market, the entrepreneurs understood the need to apply a different set of international experiential knowledge competencies, including calculation skills, to their global investments and partner selection.

4.3 From the Expansion of New Industries to the Alpha Movie

The strong commitment of Alpha’s entrepreneurs to global digital business was now based on international experiential knowledge involving strong analytical skills to support strategic planning and causal decision-making. The Alpha entrepreneurs’ international experiential knowledge and analytical skills enabled them to form informed relationships involving continuance commitment with global consumer brand firms to leverage their global mobile-game brand to exploit new industry segments (new goals). Therefore, they targeted several franchising opportunities and quickly built partnerships with global consumer brands outside of the digital community. These new collaborations brought Alpha’s management team closer to the retail markets and pushed the firm toward new growth opportunities flowing from the expansion into highly diversified global consumer markets. The strong digital brand also led to unexpected contacts from various fields interested in associating their products with digitalization and gaming (new means).

However, the new strategy was unsuccessful and led to the fragmentation of Alpha’s businesses. The entrepreneurs’ extensive international experiential knowledge meant they recognized that their brand would deteriorate rapidly if Alpha relied only on leveraging the brand through international consumer firms. Consequently, the entrepreneurs began to explore developing a new digital business area. However, as they were unaware of the precise new direction it would take, the entrepreneurs applied a means-based approach. Having dispatched one of the entrepreneurs to the United States to explore possible avenues, the entrepreneurs used effectual networking to identify the digital movie industry as a potential area of expansion. They accordingly sought to collaborate with a leading global film studio and mutual commitments were made to develop a new movie based on the Alpha brand. The movie deal is an example of how a means-based effectuation approach (what I can do) can compensate for a lack of international experience in a new field. Alpha leveraged its strong brand to push through effectual commitments in new avenues to foster brand extension, and the entrepreneurs also formed an innovative collaboration with a world-leading global film studio. In May 2016, the computer-animated Alpha movie was released and enjoyed substantial worldwide success. This success was extremely important for the future of Alpha and its brand; it strengthened its global network position, and as a result, industry leaders sought to collaborate with Alpha. The discourses of the Alpha management informants reveal they view effectuation as an important decision-making tool that enables the firm to remain agile to exploit new digital business opportunities through innovative product development.

The postscript. In September 2017, Alpha entrepreneurs announced that the firm had collected 30 million euros through an initial public offering; the firm would subsequently be listed in 2017 on the NASDAQ stock exchange. Furthermore, by 2020, the Alpha entrepreneurs launched a second movie, and Alpha became recognized as a full-fledged global entertainment company.

5 Discussion

5.1 Synthesis and the Emerging Model

This study examines how entrepreneurs’ decision-making logic and networking interact within the digital community over the course of an accelerated internationalization process. Prior effectuation research in a non-digital context has focused on entrepreneurs’ means-based approach, in which they begin with three categories of means: who I am, what I know, and whom I know (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008). From a networking perspective, a central element in the means-based approach is the entrepreneurs’ question whom I know (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019). However, digital entrepreneurs adopting the means-based approach to accelerated internationalization require prior international networks, which they do not necessarily have, as was the case in our empirical research. Hence, our investigation in the digital context expands current understanding by identifying two possible alternative entrepreneurial decision-making paths in effectuation: a novel mindset-based approach and a means-based approach. The paths reveal the changing nature of entrepreneurs’ decision-making and networking during accelerated internationalization. Figure 1 presents an emerging entrepreneurial decision-making and networking model reflecting accelerated internationalization within the digital community.

Within the mindset-based approach – a novel process revealed by our research – the entrepreneur mindset is driven by a global vision, which steers the search for new network contacts, initially with a focus on the question of how can I/we interest others? The aim is to obtain affective commitment within the digital community. For entrepreneurs lacking prior international experiential knowledge or networks, our empirical evidence suggests that utilizing pull-based digital communication channels can be effective. In that case, digital communications can reach a wide audience without relying on specific knowledge about network partners, with an objective to raise interest within a wider audience to make inbound connections. The tools involved are typically internet-enabled, such as forums and blogs, and can increase the visibility of a venture and actualize an affective commitment to stakeholders in the digital community.

The means-based approach initially focuses on what I can do. It begins with networking with existing contacts and moves to effectual commitment with the stakeholders in the digital community. Our empirical findings reveal that Alpha’s entrepreneurs were only able to adopt a means-based approach once they had acquired initial networks. When it is possible to adopt that process, it will reflect the original effectual model (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019; Sarasvathy, 2001). However, our research suggests digital ventures employ means such as prior network contacts through a push-based approach making outbound connections to a targeted audience using, for example, emails, video negotiations, and interactive social media communication channels. Thereby, the digital communication targets known network partners, eventually leading to effectual commitment to the stakeholders in the digital community. Based on above discussion, we offer our first synthesis (See also Fig. 1).

Synthesis 1: (a) During accelerated internationalization, entrepreneurs can follow (a) an initial global mindset-based approach leading to affective commitment, or (b) an entrepreneurial means-based approach leading to effectual commitment to the stakeholders within the digital community.

The empirical evidence suggests that following the effectuation process by relying on either a mindset- or a means-based approach may involve adopting new means or setting new goals. A new finding pertaining to Sarasvathy’s (2001) model is that doing so requires harnessing learning and international experiential knowledge. Typical means are, for instance, a new network contact or new learned international experiential knowledge. For the Alpha entrepreneurs, their initial use of a mindset-based process resulted in a new network contact (the MNE Beta) that bolstered their initial resources (Whom I know) and enabled the subsequent means-based effectuation process.

In the next event, effectual decision-making resulted in the entrepreneurs acquiring new international experiential knowledge relating to the constraints of being dependent on a single partner. The situation persuaded Alpha to increase the number of partners involved in subsequent key events. This evidenced a converging cycle of constraints on the transformation of the new digital artifact that brought the firm back to adopting a means-based effectual approach and asking, “What can I do.” Hence, we offer the following synthesis:

Synthesis 2: An entrepreneur that has established mutual commitment with the stakeholders within the digital community can embark on a repeated process of effectuation based on learning by following either (a) an expanding cycle of resources or (b) a converging cycle of constraints on the transformation of new digital artifacts.

Recording the changes to the discourses over time enabled us to see beyond the initial choice between effectual decision-making and causal networking (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019). The discourses revealed novel insights into the relation between learning and entrepreneurial decision-making, leading to different types of international commitments, including continuance commitment. Our findings indicate that the Alpha entrepreneurs’ effectual decision-making process and networking with the digital community generated learning. That learning, in turn, facilitated strategic causation-based decision-making and continuance commitments to international markets. This enabled the firm to make a huge investment in launching the main Alpha mobile game through digital platforms (Appstore, Google Play). Synthesis 3 below is intended to crystallize the changing process.

Synthesis 3: During accelerated internationalization, the entrepreneurs will learn while engaging in effectual networking and accumulate international experiential knowledge that enables them to engage in causation-based decision-making when actualizing continuance commitment.

Our findings also demonstrate that when the digital firm becomes mature, the entrepreneurs’ decision-making starts to resemble that of its larger and more established counterparts. The empirical evidence indicated that the entrepreneurs’ accumulated international experiential knowledge allows them to either adhere to an international experiential-based continuance commitment or return to effectuation. The latter course would demand committing to the expanding cycle of new means-based resources or the converging cycle of new goals necessary to overcome constraints to the transformation of new digital artifacts. Sticking with the new means-based approach was evident when the Alpha entrepreneurs started to expand into new industries through brand extension and the enhanced brand awareness attracted new (potential) partners. The new goals cycle was applied when the company realized that the strategy was depleting its brand value, forcing it to return to applying the effectuation process during its next iteration into film production. Therefore, our entrepreneurial decision-making and networking model of accelerated internationalization (see Fig. 1) extends earlier effectual networking research (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019) by demonstrating the feedback loops available to a mature firm. Hence, we offer the following synthesis:

Synthesis 4: As internationalization advances in a digital firm and the entrepreneurs engage in causal decision-making to attain continuance commitment, they may temporarily (a) return to effectuation by following the expanding cycle of resources or (b) the converging cycle of constraints on the transformation of the new digital artifacts.

5.2 Theoretical Contribution

The context for this study is that of entrepreneurs’ decision-making and networking within the digital community when engaging in accelerated internationalization, doing so successfully, despite lacking experiential knowledge. This phenomenon was investigated by focusing on two literature streams: entrepreneurial decision-making and digital entrepreneurship. An examination of qualitative research identified three entrepreneurial decision-making and networking paths for entrepreneurs to adopt in the course of accelerated internationalization (see Fig. 1).

This research contributes to the international entrepreneurship research field in the following ways. First, in terms of originality (Corley & Gioia, 2011), the study provides a holistic depiction of the entrepreneurial decision-making and networking paths available to digital entrepreneurs engaging in accelerated internationalization, an area on which earlier research has been silent. We thus extend effectuation theory (Read et al., 2016; Sarasvathy, 2001) and effectual networking research (Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019) by introducing the entrepreneurial mindset-based approach. That approach targets obtaining affectual commitment as an alternative to means-based effectual commitments. Our model (Fig. 1) also explains how entrepreneurs might engage in causal decision-making and the associated networking with increased continuance commitment; if they have accumulated international experiential knowledge.

Second, this study adds scientific utility (Corley & Gioia, 2011) to international entrepreneurship research. Explanations of the alternative means available to international entrepreneurs through digital networking remain underdeveloped (see e.g., Fraccastoro et al., 2021b). We present two alternative approaches: A pull-based digital communication approach that stimulates inbound contacts and eventual affective commitment among a wider audience without having specific knowledge of possible network partners; and a push-based approach in which digital communication is applied with specific network partners in mind.

Third, the current research incrementally extends the international entrepreneurship research field (Corley & Gioia, 2011): The developed model and the three associated mechanisms offer a solid basis on which researchers could build comprehensive qualitative and longitudinal research. Specifically, effectuation theory (Galkina & Atkova, 2020; Galkina & Chetty, 2015; Prashantham et al., 2019; Sarasvathy, 2001; Sarasvathy et al., 2014) and international new venture theory concerning accelerated internationalization (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994, 2005; Paul & Rosado-Serrano, 2019) could be extended to address what happens to the role of entrepreneurs as firms expand mature (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Gabrielsson et al., 2014). As internationalization advances, the decision-making may become more embedded at the firm level; however, our research indicates that the emphasis of decision-making may also start to alter between firm-level causal networking and entrepreneur-driven effectual networking.

6 Managerial Implications, Limitations, and Future Recommendations

Following Corley and Gioia (2011), our findings can guide digital entrepreneurs acting as decision-makers and managers of accelerated internationalizing firms. The findings reveal how inexperienced entrepreneurs can choose from three different entrepreneurial decision-making and networking paths to achieve commitment within the digital community. The options depend on the entrepreneurs having the skills to use appropriate digital communication tools to expand their network contacts and achieve the necessary commitment among the digital actors. The findings also show that as resources expand, the form of decision-making absorbs more causal elements, and thus, inexperienced entrepreneurs’ decision-making comes to resemble that of their more experienced counterparts. However, our research emphasizes the importance of the entrepreneur cultivating organizational agility by retaining the option to implement entrepreneurial decision-making when a new opportunity calls for it. That agility is particularly important for digital entrepreneurs operating in an environment in a state of flux. Naturally, the current study – albeit offering a nuanced and processual understanding of a successful digital firm – suffers from the limitations specific to qualitative studies. Therefore, future longitudinal and processual qualitative research as well as quantitative panel studies that could provide more insights into the applicability of our proposed model and its generalizability to different contexts would be welcome.

Moreover, the entrepreneurial decision-making model for accelerated internationalization presented in our research could prove very useful in entrepreneurial education, particularly as there is a strong demand across society to promote digital entrepreneurship, as evident, for instance, in universities being expected to produce more science-based entrepreneurs, but there being few initiatives to ensure those often inexperienced graduates can select the most viable path to follow in their internationalization.

Availability of Data and Material

Can be provided by the first author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Autio, E., Sapienza, H. J., & Almeida, J. G. (2000). Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 909–924. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556419

Bell, J., & Loane, S. (2010). ‘New-wave’ global firms: Web 2.0 and SME internationalisation. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(3–4), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02672571003594648

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality. Anchor.

Birkinshaw, J., Brannen, M. Y., & Tung, R. L. (2011). From a distance and generalizable to up close and grounded: Reclaiming a place for qualitative methods in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.19

Burr, V. (1995). An introduction to social constructionism. Routledge.

Cavusgil, S. T., & Knight, G. (2015). The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.62

European Commission. (2015). Digital transformation of European industry and enterprises. Retrieved June 16, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/9462/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

Coviello, N. (2006). The network dynamics of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(5), 713–731. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400219

Coviello, N. (2015). Re-thinking research on born globals. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.59

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Dew, N., Read, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2011). On the entrepreneurial genesis of new markets: Effectual transformations versus causal search. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 2(12), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-010-0185-1

Doz, Y. (2011). Qualitative research for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.18

Edwards, D. (1997). Discourse and cognition. Sage Publications.

Elia, G., Margherita, A., & Passiante, G. (2020). Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 150(119791), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119791

Engel, Y., Kaandorp, M., & Elfring, T. (2017). Toward a dynamic process model of entrepreneurial networking under uncertainty. Journal of Business Venturing, 3(21), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.001

Eriksson, K., Johanson, J., Majkgård, A., & Sharma, D. D. (1997). Experiential knowledge and costs in the internationalization process. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(2), 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137508829_2.

Eriksson, P., & Kovalainen, A. (2015). Qualitative methods in business research: A practical guide to social research. Sage.

Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.x

Fraccastoro, S., Gabrielsson, M., & Chetty, S. (2021b). Social media firm specific advantages as enablers of network embeddedness of international entrepreneurial ventures. Journal of World Business, 56(3), 101164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101164

Fraccastoro, S., Gabrielsson, M., & Pullins, E. B. (2021a). The integrated use of social media, digital, and traditional communication tools in the B2B sales process of international SMEs. International Business Review, 30(4), 101776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101776

Gabrielsson, M., Gabrielsson, P., & Dimitratos, P. (2014). International entrepreneurial culture and growth of international new ventures. Management International Review, 54(4), 445–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-014-0213-8

Gabrielsson, M., Kirpalani, V. M., & Dimitratos, P. (2008). Born globals: Propositions to help advance the theory. International Business Review, 17(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2008.02.015

Gabrielsson, P., & Gabrielsson, M. (2013). A dynamic model of growth phases and survival in international business-to-business new ventures: The moderating effect of decision-making logic. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(8), 1357–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.07.011

Galkina, T., & Atkova, I. (2020). Effectual networks as complex adaptive systems: Exploring dynamic and structural factors of emergence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(5), 964–995. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719879670

Galkina, T., & Chetty, S. (2015). Effectuation and networking of internationalizing SMEs. Management International Review, 55(5), 647–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0251-x

Ghezzi, A., & Cavallo, A. (2020). Agile business model innovation in digital entrepreneurship: Lean startup approaches. Journal of Business Research, 110, 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.013

Graebner, M. E. (2009). Caveat venditor: Trust asymmetries in acquisitions of entrepreneurial firms. Academy of Management Journal, 5(23), 435–472. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.41330413

Hall, C. (1997). Social work as narrative storytelling and persuasion in professional texts. Aldershot.

Haytko, D. L. (2004). Firm-to-firm and interpersonal relationships: Perspectives from advertising agency account managers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304264989

Huber, G. P., & Power, D. J. (1985). Retrospective reports of strategic-level managers: Guidelines for increasing their accuracy. Strategic Management Journal, 6(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060206

Ji, J., Plakoyiannaki, E., Dimitratos, P., & Chen, S. (2018). The qualitative case research in international entrepreneurship: A state of the art and analysis. International Marketing Review, 36(1), 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-02-2017-0052

Jiang, Y., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2019). Perceived uncertainty and behavioral logic: Temporality and unanticipated consequences in the new venture creation process. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.06.002

Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392366

Kallinikos, J., Aaltonen, A., & Marton, A. (2013). The ambivalent ontology of digital artifacts. Mis Quarterly, 37(2), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.02

Kanitz, R., Huy, Q. N., Backmann, J., & Hoegl, M. (2021). No change is an island: How interferences between change initiatives evoke inconsistencies that undermine implementation. Academy of Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0413

Kerr, J., & Coviello, N. (2020). Weaving network theory into effectuation: A multilevel reconceptualization of effectual dynamics. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(2), 105937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.05.001

Kessler, A., & Frank, H. (2009). Nascent entrepreneurship in a longitudinal perspective: The impact of person, environment, resources and the founding process on the decision to start business activities. International Small Business Journal, 27(6), 720–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609344363

Kirzner, I. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press.

Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting inter-organizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1633–1651. https://doi.org/10.5465/256824

Lipton, J. P. (1977). On the psychology of eyewitness testimony. Journal of Applied Psychology, 6(2), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.62.1.90

Luce, R. D., & Raiffa, H. (1957). Games and decisions. John Willey and Sons. Inc.

Luostarinen, R., & Gabrielsson, M. (2006). Globalization and marketing strategies of born globals in SMOPECs. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(6), 773–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.20122

Lupina-Wegener, A., Schneider, S., & van Dick, R. (2015). The role of outgroups in contracting a shared identity. A longitudinal study of a subsidiary merger in Mexico. Management International Review, 55(5), 677–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0247-6

Magnani, G., & Zucchella, A. (2019). Coping with uncertainty in the internationalisation strategy: An exploratory study on entrepreneurial firms. International Marketing Review, 36(1), 131–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-02-2017-0042

Mansoori, Y., & Lackéus, M. (2019). Comparing effectuation to discovery-driven planning, prescriptive entrepreneurship, business planning, lean startup, and design thinking. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00153-w

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055.

Nzembayie, K. F., Buckley, A. P., & Cooney, T. (2019). Researching pure digital entrepreneurship—a multimethod insider action research approach. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 11, e00103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2018.e00103

Oviatt, B., & McDougall, P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400128

Oviatt, B., & McDougall, P. (2005). Defining international entrepreneurship and modeling the speed of internationalization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 537–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00097.x

Parker, G. G., Van Alstyne, M. W., & Choudary, S. P. (2016). Platform revolution: How networked markets are transforming the economy and how to make them work for you. WW Norton & Company. Retrieved June 10, 2021, from https://www.amazon.com/Platform-Revolution-Networked-Markets-Transforming/dp/0393249131

Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual internationalization vs born-global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. International Marketing Review, 36(6), 830–858. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2018-0280

Penrose, E. (1966). The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford University Press.

Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 399–424.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103

Prashantham, S., Kumar, K., Bhagavatula, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2019). Effectuation, network-building and internationalisation speed. International Small Business Journal, 37(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242618796145

Puthusserry, P., Khan, Z., Knight, G., & Miller, K. (2020). How do rapidly internationalizing SMEs learn? Exploring the link between network relationships, learning approaches and post-entry growth of rapidly Internationalizing SMEs from Emerging Markets. Management International Review, 60(4), 515–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-020-00424-9

Read, S., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Dew, N. (2016). Response to Arend, Sarooghi, and Burkemper Cocreating effectual entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review, 4(1), 528–536. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0180

Reuber, A. R., & Fischer, E. (1997). The influence of the management team’s international experience on the internationalization behaviors of SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(4), 807–825. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490120

Rhinesmith, S. H. (1992). Global mindsets for global managers. Training & Development, 46(10), 63–69.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis (Vol. 30). Sage.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (Eds.). (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

Rosenberg, J. Associated Press. (2018). https://financialpost.com/pmn/business-pmn/young-entrepreneurs-overcome-inexperience-and-skeptics. Retrieved May 31, 2021 from https://apnews.com/900a7ece42304204b9dbeff94c489e3f

Sahut, J. M., Iandoli, L., & Teulon, F. (2019). The age of digital entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 56, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00260-8

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378020

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Effectuation: Elements of entrepreneurial expertise. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sarasvathy, S. D., Kumar, K., & York, J. G. (2014). An effectual approach to international entrepreneurship: Overlaps, challenges, and provocative possibilities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12088

Schwandt, T. A. (2001). Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Sage.

Shrader, R. C., Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (2000). How new ventures exploit trade-offs among international risk factors: Lessons for the accelerated internationization of the 21st century. Academy of Management Journal, 43(6), 1227–1247. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556347

Unni, R., & Harmon, R. (2007). Perceived effectiveness of Push vs. Pull mobile location based advertising. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 7(2), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2007.10722129

Van Mumford, J., & Zettinig, P. (2022). Co-creation in effectuation processes: A stakeholder perspective on commitment reasoning. Journal of Business Venturing, 37(4), 106209.

Van Werven, R., Bouwmeester, O., & Cornelissen, J. P. (2015). The power of arguments: How entrepreneurs convince stakeholders of the legitimate distinctiveness of their ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(4), 616–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.001

Vissa, B., & Bhagavatula, S. (2012). The causes and consequences of churn in entrepreneurs’ personal networks. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 6(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1138

Williamson, O. E. (1981). The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87(3), 548–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1138

Wiltbank, R., Dew, N., Read, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2006). What to do next? The case for non-predictive strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 27(10), 981–998. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.555

Wiltbank, R., Read, S., Dew, N., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2009). Prediction and control under uncertainty: Outcomes in angel investing. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(2), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2007.11.004

Zhou, L., & Wu, A. (2014). Earliness of internationalization and performance outcomes: Exploring the moderating effects of venture age and international commitment. Journal of World Business, 49(1), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.10.001

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital. Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Alpha’s timeline

Appendix: Alpha’s timeline

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gabrielsson, M., Raatikainen, M. & Julkunen, S. Accelerated Internationalization Among Inexperienced Digital Entrepreneurs: Toward a Holistic Entrepreneurial Decision-Making Model. Manag Int Rev 62, 137–168 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00469-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00469-y