Abstract

In this article, we examine the mechanisms of the corporate political activities of service multinational enterprises (SMNEs) operating in an emerging economy. Reporting the findings of qualitative interviews with key decision-makers in Ukraine, the article illuminates how SMNEs operating in turbulent institutional contexts can enact various corporate political strategies, including social responsibility activities, to mitigate market costs and develop legitimacy. The findings elucidate how government agencies and institutions may also invoke corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a strategy. The article makes key contributions; firstly, it underscores the complementary dynamics that exist between CPA and CSR strategies in host markets characterised by weak and incomplete institutions. Secondly, the article contributes to the relatively under-explored nature of service sector MNEs operating in such institutional contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Academic debates on how multinational enterprises (MNEs) internationalise their operations (Cuervo-Cazurra 2016; Fortwengel 2017; Regnér and Edman 2014), through foreign direct investment (FDI) and non-market strategies have focused predominantly on manufacturing and natural resource extraction firms. This is surprising given the fact that, comparing the 1990–1992 and 2010–2012 periods, global inward FDI within the service sector had grown by almost 908%, compared to 491% in the manufacturing sector (UNCTAD 2014). In general, MNEs are considered important players given their global influence and the activities in which they are confronted with a range of issues, stakeholders and institutional contexts, in both home and host countries (Kolk and Van Tulder 2010). Furthermore, recently, scholars have increasingly recognised the potential for MNEs to be not only part of the problem, but also perhaps part of the solution, with corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities being seen as having long-term implications for the international business (IB) realm (Fetscherin et al. 2010; Jamali et al. 2017; Park et al. 2014; Pisani et al. 2017; Preuss et al. 2016).

While a stream of studies on MNEs based on the service sector has emerged (Gleich et al. 2017; Kundu and Lahiri 2015; Kundu and Merchant 2008; Stevens et al. 2015), the extant IB literature has failed to keep pace with the growth of the service industries (Jaklič et al. 2012) and their associated processes of internationalisation over recent years. A decade ago, Kundu and Merchant (2008, p. 376), noted that “the challenge lies ahead in the development of theories of service multinational enterprise to explain the intricacies of service firms”. This challenge remains. There has been a dearth of research examining the ways in which service MNEs use non-market strategies (Contractor and Kundu 1998; Ghauri et al. 2014) in order to navigate the constraints placed on their business activities by turbulent and often uncertain institutional contexts (De Villa et al. 2018). This encompasses how they sustain the business micro-aspects of the corporate political activities (CPA) connected with corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions in their host countries (Saka-Helmhout and Geppert 2011; Stevens et al. 2016). Whilst the literature on non-market strategies has often been separated into the domains of CSR (Aguinies and Glavas 2012) and corporate political strategy—i.e., corporate political activity (CPA) (Lawton et al. 2013)—this article seeks to respond to calls advocating a better understanding of the interconnectivity between these two lines of intellectual enquiry (Frynas and Stephens 2014; Frynas et al. 2017; Rodriguez et al. 2006). This article seeks to address the gap in the extant literature on Service MNEs by examining the dynamics of in situ operations in relation to CPA and CSR; to do so, it focuses on Ukraine as an emerging economy context.

This article responds to calls for the examination of the effectiveness of political strategies in different contexts (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra 2016; Lawton et al. 2013a, b; Mellahi et al. 2016; Meznar and Nigh 1995) and, in particular, in the context of emerging economies (Doh et al. 2012; Hadjikhani et al. 2012). Whilst research on CPA has focused predominantly on firms located in the USA (Mattingly 2007) or in Western European countries (Hadjikhani and Ghauri 2001; Hillman and Wan 2005; Jiménez 2010), there is a clear need for more research on how firms entering emerging economies utilise forms of CPA (Puck et al. 2013). In such markets, firms face greater liability of foreignness due to the state of the institutional environments, which are in a state of flux (e.g., Hadjikhani et al. 2012; Luo et al. 2002; Zaheer 1995). As Kostova et al. (2008) highlighted, differences in the institutional environments confronting foreign firms are likely to impact on the latter’s political strategy success in developed and emerging economies. Despite the existence of studies on the importance of political stakeholders in emerging markets such as in China (Li et al. 2008), India (Elg et al. 2015) and in Russia (Okhmatovskiy 2010), there remains a dearth of empirical studies on lesser studied emerging economies—a case in point being Ukraine. While, in developed market economies, CPA focuses primarily on influencing, shaping, preventing, or gaining an early understanding of the regulatory developments affecting a firm’s market strategies (Doh et al. 2012; Lawton et al. 2013a; Jiang et al. 2015), in emerging market settings, firms often use CPA to offset any institutional voids (cf. Khanna and Palepu 2010). Our article’s empirical focus on Ukraine, an emerging economy in which the institutional framework remains fluid or void (Puffer et al. 2010), enables us to explore not just the strategic effects and outcomes of non-market strategies (Boddewyn 2016), but, importantly, also the mechanisms and processes pertaining to corporate political activities within these emerging economies. It also enables the exploration of the linkages between notions of CSR and CPA within such institutional environments (Demirbag et al. 2017).

Furthermore, while recent years have witnessed a growth in research on the corporate political strategies of foreign invested firms (Hillman and Wan 2005; Mondejar and Zhao 2013; Zhang et al. 2016), much of this attention has focused on negotiations between MNEs and host governments at the point at which the former enter a country, with a disproportionate lack of attention given to the post-entry political strategies and tactics in which firms engage (Hillman and Wan 2005; Rodriguez et al. 2006; Tasavori et al. 2015). Thus, this article provides novel insights in relation to the latter and directly responds to the objective of this Call for Articles to examine how in situ Service MNEs use CPA, connected with embedded CSR, to drive forward their business operations in different market contexts.

This article extends our understanding of mechanisms in organizational research (Anderson et al. 2006) by arguing that the corporate political activities of in situ Service MNEs are the product of entwined micro-level business-state relations. From a theoretical standpoint, our article argues for the need to move beyond focusing too heavily on macro-orientated market competition perspectives (Whittington 2012), providing, instead, theoretical frameworks that embrace and engage with how state capacity, in a variety of different contexts, impacts on firms’ strategic (micro-) choices. Rather than government influences being in decline (Khanna and Yafeh 2007; Puffer and McCarthy 2011), our findings demonstrate how, in the case of Ukraine, state capacity continues, in divergent ways, to influence specific non-market behaviours, and necessarily impacts upon the lived experiences of MNEs in such contexts. Against the backdrop of the above gaps, this article addresses the following research question:

How do mechanisms of in situ/post-entry Service MNEs CPA and CSR activities interact at the micro-level, and with what implications, contextualised in the non-Western European emerging economic context of the Ukraine?

This article is structured as follows. Firstly, we discuss the theoretical and contextual background to the study, bringing together Service MNC CPA, non-market and CSR literature within the business and management discipline. We then briefly outline the state-business relations in Ukraine. Next, the article outlines the methodology developed and employed by the study, which is followed by the presentation of our data and findings. We conclude the article with a discussion of the resultant insights, and of the implications and limitations of the findings.

2 Conceptual Background

2.1 Non-market and CSR Strategies

The study of strategy has focused primarily on the supra level of the competitive aspects of firm activities and behaviours (Bartlett and Ghoshal 2002). In consequence, the strategic literature has dedicated less attention to micro-practices (Jarzabkowski 2005) or to the institutional environment that shapes competitive strategy (Marquis and Raynard 2015). Thus, the development of an understanding of firm interaction in relation to institutional context(s) has formed the primary unit of analysis and shaped the burgeoning literature on ‘non-market’ strategies (Lux et al. 2011). The navigation of differing institutional and cultural contexts and non-market aspects constitutes an increasingly critical aspect of firm behaviours. Lawton et al. (2013a) signalled that the work on CPA that adopts a functionalist perspective tends to cast the firm’s environment as “apolitical” and “primarily concerned with regulatory compliance”, thus neglecting a multi-faceted, fine-grained, culturally contextual or more granular study of the domain (Demirbag et al. 2017).

At the broad level, the aim of non-market strategies and associated firm behaviours is generally to improve firm performance by “managing the firm’s institutional context” (Lux et al. 2011, p. 225). Thus, non-market strategies influence firm behaviours such as market entry choices (Elsahn and Benson-Rea 2018; Mellahi et al. 2016; Tasavori et al. 2015). Research on non-market activities tends to assume that firms are able to make choices about how, when, and why to engage in non-market strategic activities (Holburn and Vanden Bergh 2008). However, this may not be applicable to all context as activities such as, for example, CSR have been signalled as highly contextual (Crotty 2016; Demirbag et al. 2017). It is thus important to conduct studies that develop such contextualisation.

Furthermore, the functional perspectives of non-market strategies argue that CPA activities targeted at formal institutions generally work to ensure the mitigation of unfavourable policy changes (Henisz and Zelner 2012) and, with informal institutions, the imposition of restrictions of acceptable non-market practices (Biggart and Guillén 1999; Khan et al. 2015). Hence, in functionalist approaches, firms need to target non-market strategy activities at the key individuals who can affect policy making (Holburn and Vanden Bergh 2008), which forms the basis for CPA (Hillman et al. 2004). Thus, research on non-market strategies extends to aspects of lobbying or corruptive firm behaviours (Mauro 1995). Although this perspective on non-market strategies provides some indication of the rationale by which firms to engage in such activities, it neglects firm-level attributes such as the amalgam of CPA and CSR non-market resources and capabilities (e.g., Frynas et al. 2017). For example, a firm’s ties with specific individuals (Biggart and Guillén 1999; Dieleman and Boddewyn 2011) may provide an organization with access to resources unavailable to others. Therefore, a firm can use such partial ties to not only engage in non-market strategies, but to also mitigate political risks, with such ties forming a buffer against arbitrary institutional behaviours (Dieleman and Boddewyn 2011). However, the value of each of these ties may differ across organizations (Okhmatovskiy 2010); hence, some may enable pro-active non-market strategies while others may serve as reactive risk management of resources.

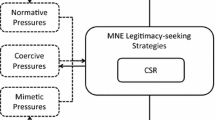

In addition to the functional perspective of non-market strategies, a more dynamic institutional theory, inspired by a deeper understanding of non-market strategies, is emerging. In this understanding, firms use non-market strategies to seek legitimacy (Reast et al. 2013) and overcome their liability of foreignness (e.g., Zaheer 1995) by, for example, aiming to influence the setting of agendas with relevant regulators or by finding access points that enable the forecasting of any changes to the non-market environment. In a review of non-market literature, Mellahi et al. (2016) found that stakeholder theory, agency theory, institutional theory, resource-based views, and resource dependency theory are often employed as theoretical lenses to examine non-market strategies. Each of these theoretical foci concentrates on different analytical levels, providing insights into how firms use non-market strategies in host markets. These underline how non-market strategic activities are used to attain legitimacy, access resources, garner support from stakeholders and develop resources and capabilities suited to navigate the competitive market environment (McWilliams and Siegel 2001).

Further important drivers of non-market literature are CSR (Aguinies and Glavas 2012; Demirbag et al. 2017) and corporate political strategy/CPA (Lawton et al. 2013a). In particular, CPA is a core aspect of non-market strategies because success in political markets facilitates success in competitive ones (Rajwani and Liedong 2015). Even more pertinent for the present argument, CPA is common to organizational activities in emerging and transition countries (Rajwani and Liedong 2015). Therein, CPA is often associated with issues of corruption, lobbying, and other activities aimed at influencing the ‘formal’ institutional environment (Lawton et al. 2013a). Within developed market economies, CPA focuses primarily on influencing, shaping, preventing, or gaining an early understanding of the regulatory developments affecting a firm’s market (and particularly entry) strategies (Doh et al. 2012; Lawton et al. 2013a). By contrast, where institutional contexts are unstable or missing, firms use CPA to offset institutional voids. This can often lead to exchange relationships between firms and the state, which can provide the former with legitimacy or, in some cases, result in them engaging in illicit and corrupt behaviours (Doh et al. 2012; Lawton et al. 2013a). Therein, Petrou (2015) noted that foreign firms might find themselves at a particular disadvantage, as they are not indigenous to established networks and therefore lack integration at both the individual and social group levels.

However, the non-market literature has hitherto focused on institutional context as a moderator of non-market strategies, with firms being able to shape and manage their contexts by engaging in such behaviours. There is less awareness of how the institutional context predicates specific firm non-market behaviours and strategies and the myriad individuals within and surrounding them. Therefore, Lawton et al. (2013a) and Frynas and Stephens (2014) issued a call to re-examine the role played by the state in the mechanics and mechanisms of non-market strategies.

2.2 Contextualising and Politicizing CSR as Part of CPA

CSR has traditionally been based upon the implicit understanding that firms voluntarily (Carroll and Shabana 2010) engage in responsible activities to which they are not legally obliged. Nevertheless, scholars have recently underscored the importance to fully understand CSR of the context within which business activities take place (Demirbag et al. 2017; Halme et al. 2009). Barkemeyer (2009) argued that Western approaches to CSR have limited relevance in non-Western institutional environments, especially in transitional countries. Moreover, Dobers and Halme (2009) argued that, in specific institutional environments in which institutions are weak, CSR may be understood and enacted in alternative ways, giving it a different ‘twist’. As a result, traditional assumptions about CSR have increasingly been challenged, with a corpus of scholars (Blasco and Zølner 2010; Chapple and Moon 2005) arguing the need for more contextualized research on CSR, one that appreciates the importance of varieties of institutional, legal, and cultural contexts (Halme et al. 2009). Recently, there has been an increase in studies on CSR in emerging and developing countries (Khan et al. 2015; Kolk and Van Tulder 2010; Park et al. 2014), including China (Li and Zhang 2010; Xu and Yang 2010). Nevertheless, within the former socialist regions of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, research has predominantly placed Russia as its empirical focus (Crotty 2016; Ray 2008).

Alongside the increased interest in how CSR is operationalized across different institutional contexts, there has been an increasingly ‘political’ turn (Scherer et al. 2016) with the emergence of the concept of ‘political CSR’ (Hadjikhani et al. 2008; Matten and Crane 2005; Scherer et al. 2016; Scherer and Palazzo 2011), which pays attention to how firms increasingly adopt governmental responsibilities beyond their economic, ethical, legal, and philanthropic ones. The firm often emerges as a ‘political actor’ in response to the regulatory vacuum, which exists around the activities of MNEs (Matten and Crane 2005; Palazzo and Scherer 2006).

As Scherer et al. (2016) argued, political CSR has emerged in response to limitations across three academic discourses. Firstly, within the international business (IB) literature—with some notable exceptions (Doh et al. 2012; Rodriguez et al. 2006)—much research has failed to fully explore the responsibilities of MNEs as a consequence of phenomena such as global sourcing and different forms of internationalization. Secondly, the continued ‘instrumental’ framing of CSR (Carroll and Shabana 2010) has assumed the existence of a demarcation between the economic and political realms and has hence failed to illuminate how, in response to the rapid forces of globalization, firms increasingly take on the provision of public goods within blurred political and economic domains. Finally, and holding particular pertinence to this article’s underlying argument, political CSR challenges the extant literature on CPA that, while explaining the conditions and the success of political strategies of firms (Hillman et al. 2004; Lawton et al. 2013; Lux et al. 2011), has remained too focused on an instrumental view of corporate politics, often taking no account of CSR research (Hillman et al. 2004). Rather than businesses simply influencing political environments in order to maximise their economic interests, political CSR sees firms becoming political actors, thus co-producing the specific institutional environments in which they operate (Scherer and Palazzo 2011).

As outlined above, we have witnessed the development of more contextualized CSR approaches and the rise of a CPA literature within business and management studies. Nevertheless, the linkages between CSR and CPA remain a neglected area of research that has the potential to contribute to the existing understanding of firm non-market strategies. This article seeks to address this gap in the extant literature not by exploring how firms jointly mediate CSR and CPA policies but, rather, by examining the relationships between CSR and CPA in SMNC contexts (Ghauri et al. 2014), exploring to what extent firms seek an alignment (Birkinshaw 2011) between these two concepts.

2.3 Non-market Strategies: The Role Played by the Everyday in Emerging Market Contexts

While the existing non-market literature has focused on the notional unit of the ‘firm’, it has failed to examine the critical importance of the processes at the micro-level of non-market strategies. Within this article, we respond by developing a micro-level focus to complement the macro-level work already undertaken. Furthermore, for Mellahi et al. (2016), the development of the non-market strategy field requires for any analyses to be conducted in tandem with other disciplines such as philosophy, sociology, and the political sciences. Consequently, we examine the non-market strategy literature alongside its broader sociological and philosophical counterparts. This enables the role played by the processual, micro and ‘everyday’ (De Certeau 1984) dimensions of non-market strategies in business-state relations to surface in the empirical context of Ukraine.

De Certeau (1984) argued that institutions and their frameworks are the prima facie ‘producer’ of order and structure and of their resultant actions in society. De Certeau termed these structural and functionalist actions as ‘strategies’ that are exercised through the central repository of hegemonic institutional power (even, in relative terms, in weak institutional environments). The aim of such ‘strategies’, within De Certeau’s casting, is the control of individual actions. In response, individuals meet these institutional-strategic power structures by developing ‘tactics’, which are about “constantly manipulating events in order to turn them into opportunities”—where said opportunities, in this case, relate to benefits to the firm (De Certeau 1984, p. xix). When strategies fail to provide the necessary conditions—i.e., in the present case, if the formal practices for business-state mediation in Ukraine alone are not sufficient—tactics provide intelligent responses to dealing with the ‘everyday’.

The ‘opaque reality of local tactics’ suited to navigate and mediate the overarching strategies outlined by the state, to which De Certeau referred (De Certeau 1984, p. xxiii), can be evidenced in the CPA practices enacted in emerging economy contexts (Marquis and Raynard 2015). Tactics do not necessarily comply with the strategies put in place by the system. Indeed, individual actions may well develop alternative ways of engaging with the purported extant system and, in so doing, contravene and subvert it.

In applying the thinking outlined above to non-market strategies, we recognise how the latter emerge in varying institutional contexts. These forms of micro-foundational assertions suggest that, within an overall institutional framework, various institutions and bodies employ ‘strategies’ aimed at directing and controlling firm behaviours (Cooper et al. 2017; Felin et al. 2015). However, individuals and firms are likely to develop and utilise ‘tactics’ in order to work alongside, by-pass, and even replace parts of the intended institutional measures and mechanisms. On an everyday basis, these actions are operationalised by individuals employing tactics suited to counter and subvert the perceived constraints and oppression imposed by the strategies adopted by the institutional system. This dynamic raises an important issue in regard to the competing legitimacies of the formal institutional structures and strategies, which are normatively deployed, and the everyday tactics adopted by individuals. As such, there is a clear need for more granular, critical, individual-focused and micro-orientated studies of the CPA and CSR domains. The article continues with a discussion of the research context of Ukraine and the methodologies employed within this study.

3 Research Context

Context remains a key issue in management and organization studies (Child 2009; Meyer and Peng 2016). As Liu and Vrontis (2017) argued, it is essential that scholars, business practitioners, and policy-makers take into consideration the ‘context’ of sociocultural, economic, political, and institutional differences, especially within the context of emerging economies. As Liu and Vrontis (2017) argued, it is important that scholars recognise that the existing assumptions and boundary conditions of the existing theories within business and management studies may need to be critically challenged and then potentially modified when the topic of examination may exist within specific and often new contexts. We now provide some necessary context to this article.

Ukraine often scores poorly in global measures of corruption; Transparency International (2015) ranks the country 130th out of 167 in its ‘corruption perception index’. The rapid privatisation of state assets following the collapse of socialism led not to the embedding of real market relations in the country but, rather, to the appropriation of state assets by those who had connections to government (Williams et al. 2013), leading to Ukraine resembling a ‘predatory’ state (Grzymala-Busse 2008). The country’s institutional environment is evolving, which presents significant challenges to MNEs; thus, in such contexts, non-market strategies take centre stage in developing competitive advantages in emerging markets and in dealing with evolving business environments (Li et al. 2013; Puck et al. 2013).

3.1 Methodological Approach

To explore the nature of the non-market strategies utilised by foreign owned SMNEs operating in Ukraine, we adopted a qualitative design. Our approach was in line with the highlighting, by recent research, of the need for qualitative studies in the field of IB (Birkinshaw et al. 2011; Doz 2011; Welch and Piekkari 2017). Engaging in an inductive research methodology enabled the generation of rich, in-depth exploratory data (Bryman and Bell 2015; Ghauri 2004; Ghauri and Firth 2009; Ghauri and Grønhaug 2010) on how foreign owned SMNEs engage in non-market strategies as a means to develop sustainable market positions within Ukraine. In order to avoid ‘regional bias’ in a country with a strong regional diversity (Rodgers 2006), our data were generated in three key regional administrative centres: Kharkiv in the east, L’viv in the west. and in Kyiv, in the centre. Kharkiv is a predominantly Russian-speaking city (Rodgers 2006) and, to this day, remains a leading centre of heavy engineering. L’viv, which is close to the Polish border, remains a hotbed of Ukrainian nationalism and European leaning. Finally, Kyiv is the capital and the governmental and commercial centre of Ukraine.

In order to overcome any difficulties in regard to sampling bias, we engaged in a referral-driven sampling method. The lead author, who had lived and worked in Ukraine for several years, generated a list of potential firms through Internet searches and by contacting the Chambers of Commerce and other business associations in the three cities. Taking into account our overarching aim of exploring how foreign-owned SMNEs operated in Ukraine, domestically owned firms were excluded from the search. The list was based on existing known ‘warm’ contacts (access is notoriously difficult in Ukraine) and on a smaller number of possible contacts provided by referral (Stokes and Wall 2014). By following this rigorous process, we sought to overcome any potential risks associated with reliance on a narrow set of social contacts and to avoid any issues regarding sampling bias. As a result, 24 in-depth qualitative interviews lasting between 45 and 90 min were conducted in 2013 with the business-managers and business owners of nine foreign-owned SMNEs operating in Ukraine. These interviews were conducted in the Russian and Ukrainian languages with the consent of each respondent. The lead author is fluent in both languages, which enabled the establishment of a rapport with the respondents and ensured consistency in the translation of the interviews into the English language. The interviewee profiles are mapped in Table 1.

The interviews were semi-structured, meaning that some respondents were able to raise a number of issues, not on the interview schedule, that were relevant and were subsequently explored further (Silverman 2013). The interviews were recorded with the respondents’ consent and then transcribed and translated. The interviews revolved around Ukraine’s general business environment, the constraints affecting the undertaking of business in the country in general and as a foreign firm in particular, the relations with state bureaucrats, and the tactics employed to generate sustainable market positions for firms.

We thematically analysed and coded the interview data in order to explore the emergent themes (Braun and Clarke 2006; Gaur and Kumar 2018; Ghauri 2004; Ghauri and Firth 2009; Ghauri and Grønhaug 2010). In keeping with Bryman (2012), the reliability of the coding was structured in order to prevent coder bias. The coding process was conducted independently by each author, with the overarching thematic categories identified to develop a coding scheme based on key themes to ensure consistent intra-coder reliability (King and Brooks 2016). The authors then applied this coding scheme, and the results were compared to ensure inter-coder reliability by identifying and addressing any discrepancies between the coders. This constant comparative method involved the continuous identification of emergent themes against the interview data and the use of analytic induction, whereby a researcher identifies the nature of a relationship and develops the narrative (Silverman 2013; Ghauri 2004; Ghauri and Firth 2009; Gaur and Kumar 2018).

The qualitative approach was particularly appropriate in enabling managers to articulate how they perceived the institutional environment and their firms’ reliance on non-market strategies to deal with institutional challenges. Quotes from the interviews are used to provide enhancement and to add voice to the study. Table 2 presents a summary of the responses to the key emerging issues and of the frequency of those responses. In many cases, consensus was found regarding the key areas of exploration; these responses could therefore be considered to be representative of the views of the majority of the respondents.

Our second and third order themes were derived by means of an iterative and comparative method (Silverman 2013). The final set of core categories emerged from our analysis of the interview data. The several themes we distilled are theorised in our discussion: formal and informal CPA, individual and institutional dynamics, outsourcing of blurred CPA activities, Aligning and blurring of CPA/CSR activities and coerced complementarity and isomorphic legitimation. We discuss each of these in turn in the following section, to which we now move to present our findings.

4 Findings and Discussion

4.1 Formal and Informal CPA: Individual and Institutional Dynamics

During the fieldwork, most of the managers interviewed spoke about the consequences of the difficulties linked to Ukraine’s transformation from a command- to a market-based economy (Williams et al. 2013). The managers highlighted that, besides ‘formal’ CPA activities such as lobbying (“We are a Russian firm and use our Chambers here in Ukraine to lobby interests through meetings with the various Ministries”, INT 10), the existing ‘rules of the game’ in Ukraine’s institutional milieu force firms to engage in explicitly corrupt activities to survive in the marketplace. Several managers outlined how they had been subjected to corruption, forced to adhere not only to the formal rules of business engagement but also to the informal rules of the game.

“We are an American owned firm. The state regulatory organs constantly check our systems. In order to gain approval, we need to pay these state officials. We’ve found out that it works like that here” (INT 14).

The institutional voids stemming from the weaknesses and or/lack of state capacity in Ukraine (Khanna and Palepu 2010; Puffer et al. 2010) were commonly mentioned by managers:

“We are a large multinational business. We have a competent tax department, which rarely makes mistakes. Here the tax administration tries, often shamelessly, to make out that we’re not paying our way correctly” (INT 24).

Individuals also spoke about the continuing legacies from Soviet times, with state bureaucrats constantly seeking to wield their ‘power’. Post-Soviet Ukraine’s chaotic attempts at economic transformation, which had been overseen by state bureaucrats (Williams et al. 2013), had led to insignificant economic reforms, but had enabled a minority elite to enrich themselves greatly (Åslund 2014), leaving the bureaucrats with pitifully low formal wages. In response, state actors have sought to ‘privatise’ their power, seeking to enrich themselves by often semi-legal or illegal means. Various non-market strategies have formed an integral part of this process. The respondents highlighted how state officials used different tactics—such as changing regulatory rules, refusing to give out and renew any necessary permits, and constantly postponing regulatory visits. As a manager of a large logistics chain summed up, “They know they have some power over us and use it for their advantage […] they make sure that we end up paying them in the end” (INT 15).

Indeed, the majority of our respondents saw the articulation of such a variety of tactics aimed at mediating, circumventing, and navigating Ukraine’s institutional milieu as something to be expected—“It’s just the way they do things here” (INT 8)—which confirmed Lawton et al. (2013a) argument that, in a weak institutional environment, informal or illegal CPA activities may become normalized within the everyday context. Several managers spoke about the importance of ‘razpil’—siphoning off—as a tactic aimed at protecting and buffering business interests by means of a network of trusted contacts:

“We have an IT business in Ukraine and across Central and Eastern Europe. The state officials constantly try to change the rules to catch us out and gain more monies for themselves. We’ve set up some ‘affiliate’ firms based in Ukraine and elsewhere. We pay these firms for services rendered and it keeps things ticking over there” (INT 18).

Such embedded networks involving ‘lubi druzi’—one’s own people—emerged during the late Soviet period as a means and a ‘tactic’ employed by individuals to navigate the intricacies of the Soviet deficit-ridden economy. Today, in Ukraine’s fluid institutional environment, they are being refashioned on monetarist terms—the obtainment of economic assets having replaced the former desire to source nearly unobtainable goods. Moreover, such findings lend weight to Rajwani and Liedong’s (2015) argument that, in some emerging economies, social capital ties can lead to manifestations of corrupt practices. Here, the contacts are ‘enabling’, in that they enable firms to avoid interaction with rapacious state actors. In many respects, our research affirms that the MNEs operating in Ukraine certainly expected, anticipated, and even embraced the use of informal practices in their engagement with state institutions.

4.2 The Outsourcing of ‘Blurred’ CPA Activities

While the respondents highlighted how managers were compelled to develop and variously enact an “opaque reality of local tactics” (De Certeau 1984, p. xxiii) in order to mediate the lack of institutional capacity in Ukraine—with the payment of ‘informal taxes’ clearly being one tactic inter alia—several managers also spoke about the difficulties they encountered, from a corporate culture perspective, in engaging in such behaviours. As a manager of an Austrian-owned IT business stated, “We know how paying a bribe gets things done quickly here, but we cannot just use our resources in this way; our bosses back home wouldn’t be pleased, let alone our shareholders” (INT 3).

In response to the need to adhere and align firm behaviours to the formal and informal rules of the game in Ukraine, often coupled with the need to simultaneously adhere to firm-level rules and policies in relation to ‘good practice and transparency’, several of the MNE managers highlighted how their firms had developed a tactic that involved the outsourcing of informal/illegal forms of CPA activities. To bypass the internal scrutiny of company bosses in the home countries and also, no less significantly, of shareholders, several firms were employing domestically-owned Ukrainian firms in ‘consultancy’ roles, charging them with the task of dealing with institutional actors. As a manager of an Austrian logistics firm stated:

“We’ve been working in Ukraine for over eight years. Things have been tough, especially at the start. Everything here seems to be ‘political’. We employ a consulting firm that provides the necessary services to smooth over issues with local bureaucrats” (INT 1).

Other respondents highlighted how local consultancy firms were paid in order “To make sure that there were no delays with import and export of our products” (INT 18); while other firms employed ‘consultants’ to ensure that government regulatory checks would all be passed smoothly (“We pay a firm who deals with all the regulatory work. Without them, we would have constant problems with the state officials”, INT 20). This ‘professionalization’ of outsourced services reflects the changing environment in which business-state and non-market relations take place in the Ukrainian context. While informal practices may have been the outcome of the ‘opportunistic’ tactics (De Certeau) adopted by firms to ‘get ahead’ and survive during the chaotic times of the 1990s, today, they have become increasingly culturally normalised and embedded practices. Moreover, several business managers explained how they employed ‘liaison officers’ whose roles were essentially those of fixers. Whilst ‘tolkachi’—a Soviet term used to identify ‘fixers’ (Rehn and Taalas 2004)—were employed by Soviet enterprises to navigate the maze of (post-) Soviet bureaucracies, today, we witness the formalization of these roles as a way for firms—particularly foreign owned MNEs—to navigate the predatory business and institutional environment Ukraine.

“In Ukraine, we employ a group of ‘security specialists’ to find out not only what our competitors are doing but also if they are breaking the law. This is useful as it gives us leverage. We need to stay focused, though, and remember that there will also be people watching us” (INT 8).

Several interviewees spoke about the dangers of ‘raiderstvo’—corporate raiding or asset grabbing—which involves the illicit acquisition of part of or the whole of a business (Hanson 2014). Such ‘asset grabbing’ involved private firms working alongside and in cahoots with a variety of institutional actors (law enforcement, tax authorities, and the judiciary), often exploiting loopholes in Ukraine’s legal system to seize private assets. Managers outlined how fixers were also being used to “keep check on what the government is thinking” (INT 17), and deal with any reputation issues related to their firms in Ukraine and protect them from any potential unwelcome interest from the state and/or other competitors.

4.3 The Aligning/Blurring of CPA/CSR Activities

4.3.1 Seeking Legitimacy

The findings suggest that most of the firms were engaged, to varying degrees, in aligning forms of CPA/CSR activities. The examples below illustrates how, upon developing their business operations in Ukraine, foreign-owned firms had chosen to engage in philanthropic activities as a way to seek legitimacy (Elg et al. 2017) across a wide range of stakeholders.

“Our firm purchased a large installation and we soon realised its importance to the city in which we work. In Soviet times, the installation had been part of a complex that had hosted social provisions for the city; nursery schools and health clinics. We have continued in that tradition and we think it’s been well appreciated” (INT 12).

As highlighted by the above example, there is a legacy of vertical paternalism originating from Soviet times, one that some firms have chosen to perpetuate as a corporate strategy in Ukraine. Moreover, our interviewed managers also noted how their CSR activities often provided social services, substituting for the state’s lack of capacity in the field. As a manager of a Polish-owned fashion retail firm stated,

“When we started our business here, we became aware that the local sports fields had become derelict. The city council was responsible for their upkeep but didn’t have any money. We stepped in and we now make sure the local people have good facilities” (INT 7).

Other managers also outlined how their firms were engaging in such ‘voluntary’ forms of CSR (Davis 1973), providing services, such as childcare, related to corporate philanthropy and social responsibility.

4.3.2 Coerced Complementarity and Isomorphic Legitimation

Traditional approaches to CSR in Western contexts assume that, when a firm engages in CSR activities, motivated by an instrumental or normative bias, it does so voluntarily (Crotty 2016). However, several business managers outlined how, since developing their business in Ukraine, their firms had increasingly been coerced into becoming engaged in CSR activities. A manager of a Turkish-owned transportation firm asserted:

“We know the rules and how things work here. When we arrived, we invested time and money in getting to know the local state elites. It was clear that there was an expectation for us to deliver not only jobs for local people and pay our taxes but to do more. We were shown some social projects in the city that needed funding. Since then, we have made strategic decisions to fund them. It works like that” (INT 23).

These sentiments were echoed by several respondents, highlighting how, in Ukraine’s weak institutional environment, in which the state actors were either unwilling or lacked the capacity to fulfil their social obligations to the citizenry, large firms, particularly foreign MNEs, were ‘asked’ and ‘expected’ to provide assistance. The ‘coerced’ nature of such CSR activities echoes similar findings reported by Crotty (2016) in her study of provincial Russia. Moreover, it theoretically highlights how, in specific institutional contexts, firms may ‘substitute’ for the state (Matten and Crane 2005). While such substituting effects were evident—“We have been asked by the state to make sure that the health centre in our district remains fully stocked with medicines” (INT 4)—they did not occur solely in Ukraine. In fact, several managers highlighted the implicit linkages between a firm’s CPA and CSR activities. A manager of a large Russian-owned IT firm stated.

“It’s like a see-saw. In theory, firms have a choice, but they don’t really. We can either engage in social projects, assisting the local government, or we’ll end up paying lots in terms of lobbying and consultancy fees. The only constant is that we’ll end up paying” (INT 11).

Here, we witness how engaging in CSR activities not only means substituting for the state in terms of its responsibilities to society at large, it also leads to substituting or ‘offsetting’ effects in terms of lobbying (CPA) costs. While we witnessed the interplay of CPA and CSR activities, complementary effects also surfaced between CPA and CSR policies. Some of our interviewed managers highlighted how, in some instances, their firms were expected to engage in both informal/illegal CPA activities and simultaneously invest resources into CSR policies.

“Where we’ve worked before, to be honest, you pay the right people and you are allowed to get on with your business. Here, things are different. We pay the right people and employ consultants to keep the state officials off our backs. However, they want more. They want us to invest in lots of social programmes too” (INT 5).

Other managers highlighted how CPA and CSR activities often “go hand in hand” (INT 10) and demonstrated how the increase in ‘artificial trust’ between business and the polity generated by the alignment of CPA and CSR activities (Liedong et al. 2015), coerced complementarity between CPA and CSR as a product of the ‘weak-strong’ nature of institutions within Ukraine’s institutional space. Moreover, both the CPA and CSR activities—in which the firms were engaging in order to adhere to the rules of the game predicated by the state—aided both firms and state alike in increasing their legitimacy across society (Kostova and Zaheer 1999) and were thus necessarily mutually reinforcing.

“We understand the rules of the political game now. We need to pay some informal taxes and also we need to fund some social programmes. We benefit from improving our reputation as a foreign business interested in local issues. For the state officials, it’s is a ‘win–win’ too. They manage to receive some monies and also show to the local population how they’ve attracted international business to the region” (INT 22).

Such sentiments represent a form of emerging organizational isomorphism in which the ‘rules of the game’ are driving the alignment and homogeneity of firm behaviours in Ukraine (Keig et al. 2015) in order to improve firm/state mutual legitimacy. However, what is significant is that, instead of driving corporate social irresponsibility (Keig et al. 2015), as might be expected, Ukraine’s corrupt institutional environment in fact drives socially responsible behaviours in conjunction with more informal/illegal corporate political activities.

5 Conclusions

This study responds to the core objectives of the Call for Articles aimed at examining how SMNEs engage in internationalisation activities; in particular, it underscores the mechanisms through which SMNEs seek to develop legitimate market positions within emerging economies (Elg et al. 2015, 2017). The article addresses the overlapping of CPA and CSR across international contexts by exploring the tactics enacted by foreign-owned SMNEs operating in Ukraine. In doing so, it contributes to the extant literature relating to how firms use non-market strategies across different institutional contexts (e.g., Ghauri et al. 2014; Lawton et al. 2013a; Lawton et al. b; Meznar and Nigh 1995); in the context of emerging economies in particular (Doh et al. 2012; Elsahn and Benson-Rea 2018). Furthermore, the article responds to calls to integrate the two dominant domains of non-market strategy of CPA and CSR (Baron 2001; Frynas and Stephens 2014; Frynas et al. 2017; Rodriguez et al. 2006).

This article contributes to the extant literature on the behaviours of MNEs within emerging economies (Akbar and Kisilowski 2015; Elg et al. 2015, 2017; Hillman and Wan 2005; Puck et al. 2013)—and, in particular, on how foreign firms utilise CPA within this context (Elsahn and Benson-Rea 2018; Puck et al. 2013)—by focusing on the mechanisms involved in non-market strategies (De Villa et al. 2018; Lawton et al. 2013a). As such, while the extant literature has focused strongly on the determinants of political strategies (Blumentritt and Nigh 2002; Meznar and Nigh 1995), there is a need for empirical analyses to be conducted not only on the outcomes of political strategies (Li et al. 2008) but also on the effectiveness of political strategies across different contexts (Demirbag et al. 2017; Getz 1997). Rather than focusing on how MNEs negotiate with host governments upon entering foreign markets (Hillman and Wan 2005; Mondejar and Zhao 2013; Zhang et al. 2016), our empirical findings extend the extant knowledge in this area by highlighting how SMNEs, use a variety of post-entry CPA and CSR tactics to navigate and offset any institutional voids (Khanna and Palepu 2010) in order to establish market legitimacy (Elg et al. 2017; Kostova and Zaheer 1999) and to overcome their liability of foreignness (Zaheer 1995).

This study contributes to the extant understandings of strategic firm responses within IB research (Doh et al. 2012; Regnér and Edman 2014) by showcasing how context and agency (MNE strategies and institutional actors) are inherently interdependent within international business settings and how they have the power to constitute each other in distinct ways (McGaughey et al. 2016). As such, this article makes an important theoretical contribution by highlighting the need to better understand the mechanisms in organizational research (Anderson et al. 2006). We argue that the corporate political activities of SMNEs in the specific emerging market setting of Ukraine are the product of entwined micro-level business-state relations (e.g., Felin et al. 2015). The findings demonstrate that SMNEs not only have to engage in political activities with the state upon entering the Ukrainian market, but also need to maintain such political activities during the post-entry stage in order to survive in contexts in which institutions are in a state of flux.

We find that SMNEs engage in a variety of CPA tactics across formal and informal spheres in order to navigate the institutional milieu in Ukraine. Our findings demonstrate how SMNEs also often tactically employ domestic Ukrainian firms to mediate and engage with the often rapacious and incoherent state bureaucracies. Moreover, in a further contribution, we find that SMNEs also engage in CSR activities—in concert with government agencies—as a device through which to execute CPA, although the institutional actors often coerce these activities. SMNEs are forced to undertake a variety of ‘social’ obligations that necessarily have a substituting effect. While the engagement in such activities clearly involves organizational and economic costs for the firm, SMNEs profit from them by improving their legitimacy (Elg et al. 2017) not only in the eyes of predatory and corrupt state officials (Lawton et al. 2013a) but also in terms of society at large and of gaining access to an attractive market (Brouthers et al. 2008).

In responding to calls to integrate approaches from different academic disciplines to extend our understanding of the nature of non-market strategies (cf. Frynas et al. 2017), this study makes the theoretical contribution of employing De Certeau’s (De Certeau 1984) framework of ‘strategies’ and ‘tactics’. By doing so, the article demonstrates how, in the specific institutional ‘rules of the game’ of Ukraine, SMNEs are forced not only to maintain strong market capabilities but also to engage in proactive CPA and CSR activities. Theoretically, our findings extend the scant attention given to the linkages between the two dominant domains within the non-market strategy literature (Frynas and Stephens 2014; Frynas et al. 2017; Rodriguez et al. 2006) by demonstrating how, in Ukraine, SMNEs are forced to align their CPA and CSR activities in the face of predatory state strategies. Seeking to move beyond the normative claims that CPA and CSR should be aligned, as a theoretical concept and contribution, our article’s findings show how, under specific institutional conditions, coerced complementarity (CSR modulating and moderating CPA) emerges as a clear tactic among SMNEs in order for them to prosper against the backdrop of evolving institutions. By engaging in CSR activities, which substitute for state inefficiencies and incapacities, SMNEs are able to also substitute these costs for reduced ‘informal taxes’ to different institutional actors. The findings highlight not only the importance of the institutional context in seeking to further examine the linkages between CPA and CSR activities, but also how an alignment between CPA and CSR activities does not necessarily lead to increased trust between firms and the polity (Liedong et al. 2015). Instead, SMNEs engage in tactics involving the alignment of their CPA and CSR activities in response to the predatory and coercive behaviours of the state. As such, in response to calls for a re-examination, at a granular level, of the function of the state with regard to the market (Frynas and Stephens 2014), our article highlights and makes managerial implications in relation to how state capacity (or incapacity) predicates specific non-market behaviours and necessarily impacts upon the lived experiences of SMNEs. Contrary to the existing literature, which states that any corrupt behaviours enacted by its competitors may impact upon an SMNE’s decision to also engage in corporate social irresponsible (CSiR) activities to maintain its market position (Keig et al. 2015), our empirical study finds that SMNEs, and the individuals within them, can simultaneously engage in pseudo-legal and informal/corrupt activities (CPA activities) and formal CSR ones. Thus, these findings offer very fine-grained micro level insights into the deployment of non-market strategies by SMNEs in emerging markets (Felin et al. 2015).

6 Implications for Practice

The empirical findings outlined in this article also have implications for business practitioners and policy-makers. Firstly, they highlight the importance of recognising the specific challenges faced by business managers of SMNEs based in developed economies when seeking to enter and, crucially, remain within often uncertain and politically risky emerging market ones. Nonetheless, firms can exploit the experience gained by operating in such ‘risky’ environments as an opportunity to develop wider in-house management learning and training, particularly in terms of strategic thinking related to entering other foreign markets by means of non-market strategies.

However, while our findings have encapsulated the dynamics and tactics that have emerged as a result of the entwined business-state relations within Ukraine, it is important to take account of the fact that a ‘one size fits all’ approach may not prove effective for SMNEs operating across diverse institutional contexts. Furthermore, when considering their strategic choices while operating within such institutional settings, business managers may also need to reflect not only on questions pertaining to their firms’ legitimacy within the host countries, but also on the views of wider firm stakeholders, including their shareholders within their home country environment and further afield. Secondly, while, in this article, we have underscored how context and agency are interdependent, it is also important to recognise that their multiple embeddedness may enable SMNEs to play proactive roles in enabling processes of institutional dynamics and change within emerging market contexts. When operating in emerging markets, managers need to carefully align both CPA and CSR in order to develop competitive advantages and survive during the post-entry stage.

7 Limitations and Future Research

In terms of limitations, this study was localized geographically within several cities in Ukraine and necessarily involved, by dint of geography, time, and political access, only a limited number of interviewees. While the views expressed by the interviewees cannot be considered to be representative of those of all business managers in Ukraine—which limits the generalizability of the findings—the value of this research lies in the rich contextual insights it provides. Further research could adopt a mixed-methods approach and expand the study topic both geographically and in terms of sample size and diversity by including other specific business sectors. Also, the study was confined to foreign-owned SMNEs operating in Ukraine. A potential avenue for future research may involve an examination of the extent to which domestically owned firms in Ukraine are similarly forced to negotiate with state structures and the extent to which SMNEs in Ukraine may gain strategic advantages by developing joint ventures with domestic firms aimed at offsetting the predatory strategies of the state. Future studies could also focus on managerial practices—by adopting a strategy as a practice lens (e.g., Jarzabkowski 2005)—on the processes behind CSR/CPA in different markets, and on the perceptions of the state actors operating in such challenging institutional environments.

References

Aguinies, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Akbar, Y. H., & Kisilowski, M. (2015). Managerial agency, risk, and strategic posture: Nonmarket strategies in the transitional core and periphery. International Business Review, 24(6), 984–996.

Anderson, P. J. J., Blatt, R., Christianson, M. K., Grant, A. M., Marquis, C., & Neuman, E. J. (2006). Understanding mechanisms in organizational research: Reflections from a collective journey. Journal of Management Inquiry, 15(2), 102–113.

Åslund, A. (2014). Why Ukraine is so poor, and what could be done to make it richer. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 55(3), 236–246.

Barkemeyer, R. (2009). Beyond compliance—below expectations? CSR in the con-text of international development. Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(3), 273–288.

Baron, D. P. (2001). Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 10(1), 7–45.

Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (2002). Building competitive advantage through people. Sloan Management Review, 43(2), 34–41.

Biggart, N., & Guillén, M. (1999). Developing difference: Social organization and the rise of the auto industries of South Korea, Taiwan, Spain, and Argentina. American Sociological Review, 64(5), 722–747.

Birkinshaw, J. (2011). Do you really know where you are going? Business Strategy Review, 22(1), 41–45.

Birkinshaw, J., Brannen, M. Y., & Tung, R. L. (2011). From a distance and generalizable to up close and grounded: Reclaiming a place for qualitative methods in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 573–581.

Blasco, M., & Zølner, M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in Mexico and France: Exploring the role of normative institutions. Business and Society, 49(2), 216–251.

Blumentritt, T. P., & Nigh, D. (2002). The integration of subsidiary political activities in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(1), 57–77.

Boddewyn, J. J. (2016). International business-government relations research 1945–2015: Concepts, typologies, theories and methodologies. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 10–22.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brouthers, L. E., Gao, Y., & McNicol, J. P. (2008). Corruption and market attractiveness influences on different types of FDI. Strategic Management Journal, 29(6), 673–680.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85–105.

Chapple, W., & Moon, J. (2005). Corporate social responsibility in Asia: A seven country study of CSR web site reporting. Business and Society, 44(4), 415–441.

Child, J. (2009). Context, comparison, and methodology in Chinese management research. Management and Organization Review, 5(1), 57–73.

Contractor, F. J., & Kundu, S. K. (1998). Modal choice in a world of alliances: Analyzing organizational forms in the international hotel sector. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(2), 325–356.

Cooper, S. C. L., Stokes, P., Liu, Y., & Tarba, S. Y. (2017). Sustainability and organizational behavior: A microfoundational perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(9), 1297–1301.

Crotty, J. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in the Russian federation: A contextualized approach. Business and Society, 55(6), 825–853.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2016). Multilatinas as sources of new research insights: The learning and escape drivers of international expansion. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 1963–1972.

Davis, K. (1973). The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. Academy of Management journal, 16(2), 312–322.

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

De Villa, M. A., Rajwani, T. S., Lawton, T., & Mellahi, K. (2018). To engage or not to engage with host governments: Corporate political activity and host-country political risk. Global Strategy Journal, 9(2), 208–242.

Demirbag, M., Wood, G., Makhmadshoev, D., & Rymkevich, O. (2017). Varieties of CSR: Institutions and socially responsible behaviour. International Business Review, 26(6), 1064–1074.

Dieleman, M., & Boddewyn, J. (2011). Using organization structure to buffer political ties in emerging markets: A case study. Organization Studies, 33(1), 71–95.

Dobers, P., & Halme, M. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(5), 237–259.

Doh, J., Lawton, T., & Rajwani, T. (2012). Advancing non-market strategy research: Institutional perspectives in a changing world. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(3), 22–39.

Doz, Y. (2011). Qualitative research for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 582–590.

Elg, U., Ghauri, P. N., Child, J., & Collinson, S. (2017). MNE microfoundations and routines for building a legitimate and sustainable position in emerging markets. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(9), 1320–1337.

Elg, U., Ghauri, P. N., & Schaumann, J. (2015). Internationalization through sociopolitical relationships: MNEs in India. Long Range Planning, 48(5), 334–345.

Elsahn, Z. F., & Benson-Rea, M. (2018). Political schemas and corporate political activities during foreign market entry: A micro-process perspective. Management International Review, 58(5), 771–811.

Felin, T., Foss, N. J., & Ployhart, R. E. (2015). The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. The Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 575–632.

Fetscherin, M., Voss, H., & Gugler, P. (2010). 30 Years of foreign direct investment to China: An interdisciplinary literature review. International business review, 19(3), 235–246.

Fortwengel, J. (2017). Understanding when MNCs can overcome institutional distance: A research agenda. Management International Review, 57(6), 793–814.

Frynas, J. G., Child, J., & Tarba, S. Y. (2017). Non-market social and political strategies—new integrative approaches and interdisciplinary borrowings. British Journal of Management, 28(4), 559–574.

Frynas, J., & Stephens, S. (2014). Political corporate social responsibility: Reviewing theories and setting new agendas. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(4), 483–509.

Gaur, A., & Kumar, M. (2018). A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. Journal of World Business, 53(2), 280–289.

Getz, K. A. (1997). Research in corporate political action: Integration and assessment. Business & Society, 36(1), 32–72.

Ghauri, P. (2004). Designing and conducting case studies in international business research. In R. Marschan-Piekkari & C. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business (pp. 109–124). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Ghauri, P. N., & Firth, R. (2009). The formalization of case study research in international business. der markt, 48(1–2), 29–40.

Ghauri, P. N., & Grønhaug, K. (2010). Research methods in business studies: A practical guide. London: Pearson Education.

Ghauri, P., Tasavori, M., & Zaefarian, R. (2014). Internationalisation of service firms through corporate social entrepreneurship and networking. International Marketing Review, 31(6), 576–600.

Gleich, W., Schmeisser, B., & Zschoche, M. (2017). The influence of competition on international sourcing strategies in the service sector. International Business Review, 26(2), 279–287.

Grzymala-Busse, A. (2008). Beyond clientelism: Incumbent state capture and state formation. Comparative Political Studies, 41(4–5), 638–673.

Hadjikhani, A., Elg, U., & Ghauri, P. N. (2012). Business, society and politics: Multinationals in emerging markets (Vol. 28). Emerald: Bingley.

Hadjikhani, A., & Ghauri, P. N. (2001). The behaviour of international firms in socio-political environments in the European Union. Journal of Business Research, 52(3), 263–275.

Hadjikhani, A., Lee, J. W., & Ghauri, P. N. (2008). Network view of MNCs’ socio-political behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61(9), 912–924.

Halme, M., Roome, N., & Dobers, P. (2009). Corporate responsibility: Reflections on contexts and consequences. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(1), 1–9.

Hanson, P. (2014). Reiderstvo: asset-grabbing in Russia. London: Chatham House.

Henisz, W., & Zelner, B. (2012). Strategy and competition in the market and non-market arenas. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(3), 40–51.

Hillman, A., Keim, G., & Schuler, D. (2004). Corporate political activity: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 30(6), 837–857.

Hillman, A. J., & Wan, W. P. (2005). The determinants of MNE subsidiaries’ political strategies: Evidence of institutional duality. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3), 322–340.

Holburn, G., & Vanden Bergh, R. (2008). Making friends in hostile environments: Political strategy in regulated industries. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 521–540.

Jaklič, A., Ćirjaković, J., & Chidlow, A. (2012). Exploring the effects of international sourcing on manufacturing versus service firms. The Service Industries Journal, 32(7), 1193–1207.

Jamali, D., Karam, C., Yin, J., & Soundararajan, V. (2017). CSR logics in developing countries: Translation, adaptation and stalled development. Journal of World Business, 52(3), 343–359.

Jarzabkowski, P. (2005). Strategy as practice. London: Sage Publications.

Jiang, Y., Peng, M., Yang, X., & Mutlu, C. (2015). Privatization, governance, and survival: MNE investments in private participation projects in emerging economies. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 294–301.

Jiménez, A. (2010). Does political risk affect the scope of the expansion abroad? Evidence from Spanish MNEs. International Business Review, 19(6), 619–633.

Keig, D. L., Brouthers, L. E., & Marshall, V. B. (2015). Formal and informal corruption environments and multinational enterprise social irresponsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 52(1), 89–116.

Khan, Z., Lew, Y. K., & Park, B. I. (2015). Institutional legitimacy and norms-based CSR marketing practices: Insights from MNCs operating in a developing economy. International Marketing Review, 32(5), 463–491.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (2010). Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Khanna, T., & Yafeh, Y. (2007). Business groups in emerging markets: Paragons or parasites? Journal of Economic Literature, 45(2), 331–372.

King, N., & Brooks, J. M. (2016). Template analysis for business and management students. Croydon: Sage Publications.

Kolk, A., & Van Tulder, R. (2010). International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. International Business Review, 19(2), 119–125.

Kostova, T., Roth, K., & Dacin, M. T. (2008). Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 994–1006.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management review, 24(1), 64–81.

Kundu, S. K., & Lahiri, S. (2015). Turning the spotlight on service multinationals: New theoretical insights and empirical evidence. Journal of International Management, 21(3), 215–219.

Kundu, S. K., & Merchant, H. (2008). Service multinationals: Their past, present, and future. Management International Review, 48(4), 371–377.

Lawton, T., McGuire, S., & Rajwani, T. (2013a). Corporate political activity: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(1), 86–105.

Lawton, T., Rajwani, T., & Doh, J. (2013b). The antecedents of political capabilities: A study of ownership, cross-border activity and organization at legacy airlines in a deregulatory context. International Business Review, 22(1), 228–242.

Li, Y., Peng, M., & Macaulay, C. (2013). Market-political ambidexterity during institutional transitions. Strategic Organization, 11(2), 205–213.

Li, W., & Zhang, R. (2010). Corporate social responsibility, ownership structure and political interference: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(4), 631–645.

Li, J. J., Zhou, K. Z., & Shao, A. T. (2008). Competitive position, managerial ties, and profitability of foreign firms in China: An interactive perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(3), 339–352.

Liedong, T. A., Ghobadian, A., Rajwani, T., & O’Regan, N. (2015). Toward a view of complementarity: Trust and policy influence effects of corporate social responsibility and corporate political activity. Group and Organization Management, 40(3), 405–427.

Liu, Y., & Vrontis, D. (2017). Emerging market firms venturing into advanced economies: The role of context. Thunderbird International Business Review, 59(3), 255–261.

Luo, Y., Shenkar, O., & Nyaw, M. K. (2002). Mitigating liabilities of foreignness: Defensive versus offensive approaches. Journal of International Management, 8(3), 283–300.

Lux, S., Crook, T., & Woehr, D. (2011). Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity. Journal of Management, 37(1), 223–247.

Marquis, C., & Raynard, M. (2015). Institutional strategies in emerging markets. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 291–335.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179.

Mattingly, J. E. (2007). How to become your own worst adversary: Examining the connection between managerial attributions and organizational relationships with public interest stakeholders. Journal of Public Affairs, 7(1), 7–21.

Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(3), 681–712.

McGaughey, S. L., Kumaraswamy, A., & Liesch, P. W. (2016). Institutions, entrepreneurship and co-evolution in international business. Journal of World Business, 51(6), 871–881.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

Mellahi, K., Frynas, J., Sun, P., & Siegel, D. (2016). A review of the non-market strategy literature: Towards a multitheoretical integration. Journal of Management, 24(1), 143–173.

Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. (2016). Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(1), 3–22.

Meznar, M., & Nigh, D. (1995). Buffer or bridge? Environmental and organizational determinants of public affairs activities in American firms. The Academy of Management Journal, 38(4), 975–996.

Mondejar, P. R., & Zhao, P. H. (2013). Antecedents to government relationship building and the institutional contingencies in a transition economy. Management International Review, 53(4), 579–605.

Okhmatovskiy, I. (2010). Performance implications of ties to the government and SOEs: A political embeddedness perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1020–1047.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 71–88.

Park, B. I., Chidlow, A., & Choi, J. (2014). Corporate social responsibility: Stakeholders influence on MNEs’ activities. International Business Review, 23(5), 966–980.

Petrou, A. (2015). Arbitrariness of corruption and foreign affiliate performance: A resource dependence perspective. Journal of World Business, 50(4), 826–837.

Pisani, N., Kourula, A., Kolk, A., & Meijer, R. (2017). How global is international CSR research? Insights and recommendations from a systematic review. Journal of World Business, 52(5), 591–614.

Preuss, L., Barkemeyer, R., & Glavas, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in developing country multinationals: Identifying company and country-level influences. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(3), 347–378.

Puck, J. F., Rogers, H., & Mohr, A. T. (2013). Flying under the radar: Foreign firm visibility and the efficacy of political strategies in emerging economies. International Business Review, 22(6), 1021–1033.

Puffer, S., & McCarthy, D. (2011). Two decades of Russian business and management research: An institutional theory perspective. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(2), 21–36.

Puffer, S., McCarthy, D., & Boisot, M. (2010). Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The impact of formal institutional voids. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 441–467.

Rajwani, T., & Liedong, T. (2015). Political activity and firm performance within non-market research: A review and international comparative assessment. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 273–283.

Ray, S. (2008). A case study of Shell at Sakhalin: Having a whale of a time? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(3), 173–185.

Reast, J., Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Vanhamme, J. (2013). Legitimacy-Seeking organizational strategies in controversial industries: A case study analysis and a bidimensional model. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 139–153.

Regnér, P., & Edman, J. (2014). MNE institutional advantage: How subunits shape, transpose and evade host country institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(3), 275–302.

Rehn, A., & Taalas, S. (2004). ‘Znakomstva I Svyazi’(Acquaintances and connections)–Blat, the Soviet Union, and mundane entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(3), 235–250.

Rodgers, P. (2006). Understanding regionalism and the politics of identity in Ukraine’s Eastern Borderlands. Nationalities Papers, 34(2), 157–174.

Rodriguez, P., Siegel, D. S., Hillman, A., & Eden, L. (2006). Three lenses on the multinational enterprise: Politics, corruption, and corporate social responsibility. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 733–746.

Saka-Helmhout, A., & Geppert, M. (2011). Different forms of agency and institutional influences within multinational enterprises. Management International Review, 51(5), 567–592.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2011). The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48(4), 899–931.

Scherer, A. G., Rasche, A., Palazzo, G., & Spicer, A. (2016). Managing for political corporate social responsibility: New challenges and directions for PCSR 2.0. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3), 273–298.

Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. London: Sage Publications.

Stevens, C. E., Makarius, E. E., & Mukherjee, D. (2015). It takes two to tango: Signaling behavioral intent in service multinationals’ foreign entry strategies. Journal of International Management, 21(3), 235–248.

Stevens, C. E., Xie, E., & Peng, M. W. (2016). Toward a legitimacy-based view of political risk: The case of Google and Yahoo in China. Strategic Management Journal, 37(5), 945–963.

Stokes, P., & Wall, T. (2014). Research methods. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Tasavori, M., Zaefarian, R., & Ghauri, P. N. (2015). The creation view of opportunities at the base of the pyramid. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 27(1–2), 106–126.

Transparency International. (2015). Corruption perceptions index 2015. Berlin: Transparency International.

UNCTAD (2014). World Investment Report, Annex Table 26—Estimated World Inward FDI Flows, by Sector and Industry, 1990–1992 and 2010–2012.

Welch, C., & Piekkari, R. (2017). How should we (not) judge the ‘quality’ of qualitative research? A re-assessment of current evaluative criteria in International Business. Journal of World Business, 52(5), 714–725.

Whittington, R. (2012). Big strategy/small strategy. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 263–268.

Williams, C. C., Round, J., & Rodgers, P. (2013). The role of informal economies in the post-Soviet world: The end of transition?. London: Routledge.

Xu, S., & Yang, R. (2010). Indigenous characteristics of Chinese corporate social responsibility conceptual paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 321–333.

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341–363.

Zhang, Y., Zhao, W., & Ge, J. (2016). Institutional duality and political strategies of foreign-invested firms in an emerging economy. Journal of World Business, 51(3), 451–462.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodgers, P., Stokes, P., Tarba, S. et al. The Role of Non-market Strategies in Establishing Legitimacy: The Case of Service MNEs in Emerging Economies. Manag Int Rev 59, 515–540 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-019-00385-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-019-00385-8