Abstract

Building on a business network perspective, the aim of this paper is to present a theoretical view for studying service MNEs in ICT (information communication technology) projects centred on the improvement of public services. The four interrelated concepts of cooperation, legitimacy, commitment and knowledge are applied in the analysis of two projects. Defining the projects as object-based services, the study manifests how service MNEs manage three types of actors (business, political and social) having their legitimacy in different systems. The cases illustrate cross-border activities where MNEs from Sweden, Spain and China join forces in Brazil with local business, social and political actors and cooperate to strengthen their competitive market position. The study concludes that successful cooperation is partially explained by the management’s ability to incorporate business resources into the needs of the socio-political actors. Furthermore, in object-based services, which are not similar to long-term business relationships, the three involved parties advance different types of relationships within a loose network structure. A key implication is that extensive public–private relationships are needed even when MNEs enjoy an established position in a foreign market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Fierce competition in foreign markets has encouraged multinational enterprises (MNEs) to engage in solving social problems since this can leverage business profits and, at the same time, increase MNEs’ legitimate position to non-business actors. Service MNEs, especially the ones belonging to the ICT (Information and Communication Technology) industry, have the potential to promote social progress with technologies that create inclusive growth, and increase business efficiency and innovation, mainly in developing markets (World Bank 2016). These MNEs increasingly provide technologies and services that contribute to societal improvements such as the development of applications in education, health and transportation, to name a few. Services developed through ICT technologies can also reduce the growth disparities between rural and urban areas (World Bank 2016) and have the potential to impact a country’s development when it comes to issues such as environmental sustainability and poverty reduction, which is in line with the United Nation’s millennium goals. As will be illustrated in this paper, the mitigation of such problems creates interdependence between private and public interests, and it becomes crucial to balance the interests that such cooperation between business and non-business actors may generate.

The increasing interchange between MNEs and non-business actors in recent years has attracted researchers studying the internationalisation of industrial firms. But despite the increasing role of pure service or services connected to products, research on how these MNEs manage their social and political environment has remained almost non-existent (Ghauri et al. 2012). Disregarding whether those in question are industrial or service firms, researchers like Polonsky and Jevons (2009), Hadjikhani et al. (2012) and Marquina and Morales (2012) have a general consensus that the management of social and political environments is the key marketing strategy that influences competition, market image and success in entry and expansion into foreign markets (Ghauri et al. 2012). Hence, relationships with socio-political actors are particularly relevant for service MNEs that operate globally and often find themselves embedded in a network structure containing both business and non-business actors (Jansson et al. 2007). Although the management of socio-political relationships has been recognised as an important strategic tool to help MNEs build legitimacy at home and in host markets (Hadjikhani et al. 2008), the interaction between business, policy makers and society remains underexamined in international service marketing, at least in comparison to the traditional networks of industrial firms.

When studying the internationalisation of service firms, researchers have focused on issues like the connection between internationalisation and the degree of intangibility or types of services. Considering the heterogeneous nature of services, researchers question whether theories concerning the internationalisation of goods can equally be used for all services and the following four idealised types have been suggested (Clark and Rajaratnam 1999): (a) contact-based services (such as consultancy services), (b) vehicle-based services (such as communication via wires and satellite, (c) asset-based (such as banks) and, (d) object-based (services integrated with physical objects). This paper concerns projects with an object-based mode of internationalisation, where MNEs in ICT projects promote social progress with electronic technologies creating inclusive growth, business efficiency and innovation.

Following the call from researchers, as well the increasing role of the service industry in the world economy (according to UNCTAD 2014, the service sector accounted in 2010 for 66.3% of global GDP), this paper contributes further knowledge on how firms in the service industry manage their relationships with socio-political actors in foreign markets. Research examining such relationships within international business and management literature tends to focus on the macro-level of activities commonly anchored on an MNE’s internationalisation phase (e.g., contact with host governments, trade associations, etc.). However, as Salmi and Heikkilä (2015) state, studies focusing on strategic activities are necessary when MNEs already have an established position and an ongoing business activity in a foreign market. So, our research question is: How do established international service firms cooperate with business and non-business actors to expand in the local foreign market? Building on empirical data from Brazil, the purpose of the paper is to present a theoretical view for studying service MNEs in international projects, and hereby contribute with further understanding of the interaction between the three actors—MNEs, society and political. By including both social and political actors in the business network, the study enhances our comprehension of firms’ entire market behaviour (Hadjikhani et al. 2016; Ring et al. 1990).

Building on a business network perspective, a theoretical view is presented and applied to the analysis of two ICT projects in Brazil. The theoretical framework consists of the four interrelated concepts of cooperation, legitimacy, commitment and knowledge and permits inclusion of the three heterogeneous actors into one united pattern for further understanding of their behaviours. The case analysis shows how these actors cooperate and solve conflicts despite their differing goals. The empirical illustration also contributes with knowledge to service MNE literature by presenting complex relationships where differences in goals, values and organisational practices require managerial abilities to minimise conflicts, and leverage business opportunities. The socio-political context also provides managerial implications to practitioners, who gain a more systematic understanding of their relationships in the political arena. While our main concern will be MNEs’ cooperation with public officials, interactions with civil society represented by NGOs (non-governmental organisations) will also be taken into account.

After a short summary of earlier contributions and a presentation of the conceptual framework, a method section follows where our qualitative study including two cases is described. The cases involve service MNEs within the ICT industry from Sweden, Spain, China and Brazil, working together with public officials and NGOs to improve public service in two Brazilian cities. We end the paper with a conclusion showing the complexities of relationships forming public-private interactions in service MNEs.

2 Earlier Contributions

In the introduction, we have pointed to the importance of studying firms interactions with non-business actors in an emerging market context. But how much research has been done within this area in the last decade? A search in Business Source Complete (2018), an extensive database covering more than 2100 active, full-text journals within business and economics, reveals the following for the period January 2010–June 2018: (The search was limited to peer-reviewed academic articles).

As can be seen in Table 1, almost 2800 articles deal with the internationalisation of companies, while fewer—584—have a focus on service firms. When ‘internationalisation of firms’ is combined with ‘emerging markets’ 379 articles are identified, while the number decreases to 67 when related to service firms. From the table it is also clear that more articles are dealing with ‘social’ rather than ‘political’ aspects and that only one article is found when ‘internationalisation of firms/service firms’, ‘emerging markets’ and ‘sociopolitical’ are combined. The article ‘Internationalization Through Sociopolitical Relationships: MNEs in India’ by Elg et al. (2015) was published in 2015 and the authors point to the importance of more empirical studies, including MNEs from varying countries.

Hence, this study encounters the three research paths of MNEs in services, politics and society in an emerging market context. As indicated in the table above, each of these paths has attracted a number of researchers, though each with a different theoretical and empirical basis. A service can be defined as internationalised when it operates in a foreign country, employing one or more of the four classifications stated in the introduction. The classifications further determine if and how the services become interconnected to business, society and political issues in foreign countries. Given the diversity in the nature of the service, internationalisation researchers state that no single theory is likely to be correct (see for example Richardson 1987). Authors like Clark and Rajaratnam (1999) connect the selection of a theory to the types and nature of services. In this vein the internationalisation model becomes related to the degree of, (a) intangibility, (b) heterogeneity, (c) perishability and (d) inseparability. While the first type (contact-based) presents the classic nature of services and interaction, the other types allow producers to be present without actually crossing national borders. But governments try to exercise a form of control, for example, in how information or communication is transmitted across their boundaries (Ross and Crossan 2012). ICT projects are mostly object-based, and the social goals are driven by mutuality and interdependence among the involved parties.

Earlier theoretical contributions related to the topic of this paper are studies of governments’ coercive or/and supportive actions. The studies range from the presumption that management is a function of a response to the political environment (Cui and Jiang 2012; Meyer et al. 2014), to the design of coping strategies. The coping strategies view is often dealt with as the management of risk (Miller 1992), country risk ratings (Cosset and Roy 1991) or corporate structure (Cui and Jiang 2012). The focus of these contributions is mainly on a one-dimensional impact, i.e., the hierarchical power of political organisations and their impact on the firms’ market activities. Rather than focusing on service internationalisation, extensive attention has been given to topics related to international financial crises and the role of corporate governments (Ross and Crossan 2012) and governments (Howcroft et al. 2010). Linking economic crises to the role of governments involves issues from the interdependence of financial systems, to the behaviour of governments in different countries (Mendoza and Smith 2014), and their impact on social welfare (Benigno and Fornaro 2014). Hence, the presumption of one-sided action of political organisations to regulate the market, which is based on economic theories, suffers from a rather passive perspective. However, in line with Crane and Desmond (2002) and Hadjikhani et al. (2012), and building on a business network perspective, we suggest a triadic view for the analysis of relationships between non-business and business actors, i.e., actors from different spheres are seen to be actively influencing each other.

In recent years, it has been highlighted that the government and public expect MNEs to play critical roles in economic development, but also to engage in broader societal contributions (Yin and Zhang 2012). However, one limitation of these studies is that they mainly consider interactions with social actors such as NGOs, while not including the political actors. In this paper, the intention is to explore the interplay, and give insights into the cooperative behaviour of the three parties belonging in different systems.

2.1 A Theoretical View

Business relationships have been extensively explored in industrial marketing (see e.g., Ford et al. 2011) and international business studies (see e.g., Forsgren et al. 2015). But these studies rarely include relationships between socio-political and business firms. As illustrated above, our study goes beyond this mainstream view and, in line with the perspective of recent researchers like Hadjikhani et al. (2016), constructs the assumption that MNEs in the service industry are interwoven in a network containing both business and non-business actors (political and societal actors). The paper departs from the view that the business context includes the entire market, i.e., each different type of actor. The notion is that the strength of an MNE’s position is determined by its behaviour in three interrelated arenas: business, society and political. The MNE’s legitimate position includes its management of relationships with actors from both the business and political arenas, that secures the mutual gains of the involved firms, society and political actors. While the aim of the MNEs is to undertake strategic actions to develop new social solutions and improve their market position, political actors, such as government and public officials, cooperate with business actors to support projects for the demands of the people, with the purpose of improving their legitimate position. It lies in the long-term interests of the MNEs and also of the political actors, to manage the environment and gain business, political and social support for their actions (Ghauri and Park 2012; Nicholson and Salaber 2013). Therefore, relationships here are seen to include actors, some with a generalised exchange, while others have a specific exchange in the network, and, contrary to the industrial network, the reciprocity is not necessarily achieved through any direct benefit to one actor over another but may be achieved through an indirect benefit provided by another actor.

Hence, the theoretical view developed in this paper is based on an extended business network perspective (Thilenius et al. 2016). Similar to the business arena, the non-business arena is heterogeneous. Besides the government, it involves units like public officials, as well as other non-business actors functioning as intermediaries between the MNEs and the political units. While political actors, like government and public officials, put stress on the procurement setting for the needs of the society, service MNEs develop new technological solutions to satisfy the actors involved.

Political actors use their legitimate position to affect the market, and they determine and implement market rules that affect groups of firms homogeneously. The aim of business firms, on their part, is to undertake strategic actions towards governments and cooperate, to gain specific support and improve their legitimate market position. The cooperative activities are seen in this study from the perspective of the firms’ market legitimacy, combined with knowledge and commitment. Knowledge is composed of general and specific technological competence and social information about the parties in the network context. In this network, cooperation concerns activities involving both business and socio-political actors for developing new solutions. Legitimacy is defined as the position recognised by the surrounding actors in a business network. It is based on the strength and type of ties between a focal unit and others in the environment. Development or maintenance of a legitimate position is emphasised with different types of resources, including social and/or technological resources by the committed actors (Meyer et al. 2014). The greater the available business and political resources, the stronger the legitimate position of the firm in the market will be.

The actors’ knowledge of each other affects the level of cooperation. Knowledge can be explained in terms of the information available not only concerning the needs of the specific counterparts but also those of the partner and his connected actors (Sammarra and Biggiero 2008). It can, for example, encompass social, economic and technological aspects. However, to acquire political knowledge companies need to make commitment actions, which, for example, can include the establishment of a unit in a firm’s organisation to deal with all the information necessary for meeting the demands of political actors and the institutional environment. Political knowledge is information about political decisions, political decision makers and understanding the needs of the connected actors (such as consumers who will become affected by the decision). Investments are made in order to elaborate on the understanding of the network of relationships surrounding political units, and also their needs and available resources. Knowledge about political and social values is necessary because political actors are expected to satisfy different political and social groups with conflicting demands (Boddewyn and Doh 2011; Choi et al. 2014). Political organisations themselves are embedded with actors such as the media, voters, unions and people (customers), all of whom direct their actions differently. Due to MNEs’ knowledge about these actors, their needs and desires, the firms can become very influential. Hence, business and socio-political actors cooperate to perform specific activities and gain knowledge and legitimacy. Conversely, lack of knowledge, misunderstandings or lack of ability to manage social and political demands will have a negative effect on relationships, with cooperation turning into conflict.

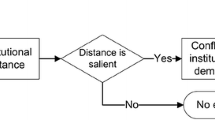

Thus, as illustrated below, the theoretical view is composed of the four interrelated concepts of: (a) knowledge, (b) commitment, (c) legitimacy and (d) cooperation (see Fig. 1). This view implies that MNEs form three different types of connection with three different bases for legitimacy, holding different knowledge and requiring different types of commitment needed for cooperation, in order to strengthen the MNE’s competitive market position. In this structure, business legitimacy is determined by the evaluation of connected actors including not only suppliers and customers, but also those in their non-business context. Political legitimacy relies on interaction with political actors reached from evaluation of the public, media and society, as well as business firms. Political actors also show gains in legitimacy when they can show commitment through cooperation with MNEs with a strong reputation. This can benefit political actors as they can show the gains in economic prosperity needed to keep their political or social position. Firms’ legitimacy is thus constructed by an accumulation of legitimacies reached in both business and non-business markets. However, legitimacy does not last forever, and it can be challenged at any point in time. Hence, even when an MNE enjoys a legitimate position in a foreign market, activities for sustaining legitimacy are vital to assure the firm’s growth. Conversely, a lack of legitimacy or deficit in legitimacy can become a liability of outsidership (Johanson and Vahlne 2009) and have a negative impact on the MNE’s competitive market position.

3 Method

The analysis of the two cases is used to understand the main incentives for both business and socio-political actors to engage in cooperative forms of interaction. The case study method in a more complex cooperative structure, for instance the public-private structure, is helpful when attempting to capture actors’ differences in values, beliefs and intentions (Yin 2015). Moreover, the case study method is particularly attractive when ‘how’ questions are to be answered (Ghauri and Grønhaug 2005) and when the focus is on the phenomenon in a real-life context-specific situation (Yin 2015). Our choice is in line with Ghauri and Firth's (2009) view, that a case study allows the examination of the phenomenon in many dimensions and then facilitates a cohesive research interpretation. Therefore, we have applied a network perspective and consider actors’ different viewpoints in order to get a holistic explanation of the phenomena.

With regards to case selection, we considered factors such as product/service innovation, an emerging economy context and community impact. Although the cases involve projects within one country, we bring an international dimension since the firms involved are from several countries. For the data gathering, two strategies were used: 70 in-depth interviews collected in two periods (2013–2014) and (2015–2017) and the analysis of secondary sources (e.g., local/international news, company reports, etc.). The combination of interviews and secondary data allowed triangulation across and within data sources (Gibbert et al. 2008). Interviews were conducted with employees working for companies and other organisations (non-governmental, public officials and political authorities) that were involved in the project. Some interviews were in English, but the majority were in Portuguese. Most interviews were conducted face-to-face and some respondents were interviewed more than once (see Table 2 below). Questions were divided into: (1) detailed questions about the development of the business-socio-political relationships before, during and after the projects and (2) how such relationships strengthened the MNEs’ competitive market position. Respondents were chosen based on their direct involvement in the project, and subsequently a snowball technique has been used (Patton 2005).

N-Vivo has been used to code the data systematically. We follow Sinkovics et al. (2008) argument that the use of qualitative software can contribute to more reliable research findings and then support theory building. When analysing the data, we started by separating information for each case. First-order open codes were then developed based on the informants’ own words, aiming to identify emerging themes (Ghauri and Firth 2009). This resulted in an analysis of activities and respondents’ motivations and expectations developed before and during the project. We then generated second-order codes with a more specific theoretical background in mind, such as theory on political connections. Finally, the third round resulted in a more abstract level of coding in which knowledge, commitment and legitimacy emerged as key elements within business and socio-political cooperation, which allowed the design of our theoretical model (see Fig. 1).

3.1 Case Description

The cities in which the smart city projects have been developed and implemented are located in Brazil. The country deserves a brief overall description from a social and economic perspective. In 2012, the Brazilian economy was booming. An emerging and growing middle class was expanding its domestic consumption, and this attracted new foreign direct investment (FDI). With a population of over 200 million inhabitants, the Brazilian market provides great business opportunities. Brazil’s economic and social progress between 2003 and 2014 raised 29 million people out of poverty. The income level of the poorest 40% of the population rose on average by 7.1% (in real terms) between 2003 and 2014, compared to a 4.4% income growth for the population as a whole (World Bank 2017).

Despite the positive Brazilian context when this study started in 2012, unexpected economic, social, and political changes have impacted the Brazilian economy in recent years (2014–2017). For instance, the impeachment of the president has contributed to undermining the confidence of consumers and investors. Combined with political instability, the Brazilian economy has recently faced an increasing level of unemployment and economic stagnation. Such a dramatic change, and the country’s current overall context, depict quite well what Hadjikhani and Johanson (1996) define an emerging economy as being a ‘turbulent market’. With regard to innovation, indexes provided by World Bank (2017) show that Brazil is in a worse position in comparison to OECD countries in terms of number of patents, scientific publication and the number of students graduating in technology and engineering (Esteves and Feldmann 2016). While this reflects the country’s dependence on imported technologies, it can be a source of business opportunities for service MNEs from the ICT industry, not least if such technologies can be tailored for social progress. Hence, in a business environment which combines both opportunities and challenges, Brazil has become an interesting market to study, primarily when observation leads to an understanding of the strategies used by firms to succeed in such an unstable market.

The two projects presented in this paper are linked to the ‘smart city concept’ where interaction involved business, local government and NGOs. Case 1, named “The smart city project on urban mobility”, was an initiative that came from the local government, while case 2, named “Smart City”, was an initiative that came from the private sector to leverage business opportunities. Before describing the cases, it is relevant to present what a smart city is. United Nations define it as “an innovative city that uses ICTs and other means, to improve quality of life, efficiency of urban operation and services and competitiveness, while ensuring that it meets the needs of present and future generations, with respect to economic, social and environmental aspects” (UNCTAD 2014, p. 3) Therefore, transforming a city into a ‘smart city’ is particularly interesting to service MNEs, mainly if the government become early adopters of such technologies, which then act as catalysts for broad scale application (Zanella et al. 2014). Next, the cases will be further described with focus on the planning and implementation phases.

3.2 Case 1 “Smart City Project on Urban Mobility”

The project took place in Curitiba, a city well-known for its innovative BRT system (Bus Rapid Transit) which involves bus-only lanes that allow buses to travel efficiently along their routes without having to compete with other modes of transportation. It has received both national and international attention and was also acknowledged by UNFCCC (United Nation Framework of Climate Change Convention) as an innovative transport solution generating visibility for all actors involved.

The aim of the project was to introduce 3G technology to the city’s buses along with the development of an operational control centre (OCC) that could permit fleet monitoring and management in real time. In the project, buses, OCC, cameras, traffic lights and bus stops were connected via a mobile network. The main companies involved in the project were the Swedish firm Ericsson (which develops hardware and software for telecom services), the Brazilian firm Dataprom (whose business is the development of hardware/software for transport solutions) and the Spanish firm Telefonica/Vivo (a telecom operator that provides connectivity between devices). In addition, two non-business actors, URBS and ICI, were also involved in the project. URBS is a state-owned organisation whose main task is the operation and supervision of the city’s transit system, while ICI is a non-profit organisation responsible for the supply of IT (information technology) solutions to URBS. The municipality, through URBS, invested over 10 million USD in the project.

3.2.1 Planning Phase

URBS was facing several communication problems when monitoring the city’s transport system. The flow of information between URBS, private companies, bus drivers and passengers was very limited, besides the huge amount of manual work that was required to control the city’s transport and transit. URBS used an internal procedure called ‘vehicle control record’ to provide the plan of timetables and bus routes. Usually 3500 records were filled manually, and all the information gathered in one month took almost three months to be processed. Hence, there were constant delays and complaints.

In order to deal with the communication and transit problems, URBS joined forces with ICI to identify ways to increase efficiency in the city’s transport system. Together, they identified that implementing 3G technology could be a way to solve the problem, helping operators to predict demand and in turn improve bus schedules and routes. However, the implementation of such a solution was not as simple as it first appeared. It required several adjustments and adaptations to meet the city’s needs.

Despite being a software developer for URBS, ICI did not have a technological solution available in-house, so they coordinated the project together. There were 20 technicians from ICI working on the project. In addition, a study for economic feasibility was performed by LACTEC—a non-profit institute of scientific research and technology—whose advice was to build an operation control centre (OCC) to monitor the bus fleet via cameras connected to the centre online. The study was ordered by URBS to gain knowledge about how to improve the public services. The main recommendation was staff training, and revenue generation by installing cameras inside buses, enabling communication between URBS and its passengers, and serving as a marketing platform for companies to advertise. At the end of 2009, after agreeing to move forward, the first strategy was a partial adjustment of the electronic ticketing developed by Dataprom. The target was to have a system that allowed the use of a USB broadband modem inside Dataprom’s equipment. In the meantime, URBS and ICI were looking for a telecom operator that could provide the connectivity.

3.2.2 Implementation Phase

Telefonica/Vivo was chosen due to its commitment to increase broadband coverage in several parts of the city. URBS bought around 3100 of Telefonica/Vivo’s chips for connectivity. At the end of 2011 and beginning of 2012, URBS set up an OCC and a similar centre was also implemented at Setransp in order to facilitate communication between URBS and the private transportation companies. Setransp is a trade union formed by 23 transport companies whose mission is to safeguard the interests of its members. As mentioned previously, the buses belong to the private companies and the government outsources the service. To implement the system, it was necessary to coordinate training for URBS and Setransp’s employees, involving 140 people, with 70 from each side. However, an OCC at Setransp was not a requirement from URBS but from the transport companies which were sceptical about the system. Hence, there were tensions between URBS and the transport companies who wanted to have more control over the system.

Once OCC was implemented, the new system did not function properly, and communication was lost several times. The main problem was that Telefonica/Vivo’s USB modem was being used under atypical conditions, causing data loss and malfunction. To solve the problem, technicians identified the need for a technology that could protect the USB from the external environment. Ericsson’s mobile broadband modules, originally developed for notebooks, appeared to be the right equipment and Ericsson sold 3000 modules at once. Finally, when all technologies were implemented and integrated into all equipment, a new communication problem arose in some areas of the city. Setransp was worried that the failure would impact their revenues and asked for a meeting to discuss the source of the problem.

Setransp’s manager stressed that the companies accused each other for the poor functioning of the system. Ericsson was accused of supplying a malfunctioning modem, while Telefonica/Vivo was accused of connectivity problems. Dataprom was also put under strong pressure, accused of failing to adjust its software. For URBS, Dataprom’s equipment was not working and it took some time to convince URBS that the problem was with the connectivity. Tensions and misunderstanding increased between the partners. Dataprom’s solution manager declared that it was tense when, for instance, Telefonica/Vivo’s manager stated that they were doing their best but Dataprom’s manager stressed: “Your best is bad for me! Should we try another telecom instead?” It turned out that the problem was with the connectivity, since Telefonica/Vivo had mismatched the city’s need for investment in the network. Once the coverage was applied correctly the system worked accurately. However, besides the technical problems, Telefonica/Vivo’s managers stressed the internal procedures to deal with political actors. In the MNE, there are different groups of managers dedicated to building relationships with different levels of the government. Managers emphasise the difficulties of developing and building relationships with the local mayors. They explained that “in the large cities the politicians and the public officials have a better knowledge of technology, while in the small cities most of the time it is necessary to educate them about the benefits and their impact on the municipality. Such a lack of knowledge makes it crucial for us to explain and inform them in the process of negotiation.”

When asked about the impact of the partnership in the companies’ business, Ericsson’s CSR consultant highlighted that: “The modules were developed for computers; it was the first time that we were using them in buses.” Asset tracking and transport became, therefore, a new market for the company and the project has since then been used globally as a reference case. The head of marketing and strategic department at Ericsson highlights the importance of developing projects. “A pilot project is very important to present. If it is a successful story it generates confidence in the market and in government eyes”, he stated. As, like Telefonica/Vivo, Ericsson also has a unit inside the organisation committed to dealing with and understanding what is important for the political actors. Both Ericsson and Telefonica/Vivo joined efforts to create a video, showing URBS’ president and the city mayor, as well as citizens, advocating in favour of the new technology.

On the political side, the project has been heavily used by the mayor in office, Richa, during the project. In his political campaigns (both in 2010 and 2014) innovative projects related to urban mobility were emphasised. His message was: “I will continue to invest in innovative projects to improve Parana’s urban mobility.” Hence, the mayor tried to link his image to the issue of urban mobility, and his campaign highlighted that: “Richa is the only mayor in Brazil to receive an award in the name of Curitiba City, in Washington DC for its Sustainable Transport, as well as being invited to talk at the World Week of Urban Mobility in Seoul.” Figure 2 presents a network view of the actors connected to each other in different phases of the project. The public sector is represented in striped black, while grey and black represent non-profit and business actors, respectively.

3.3 Case 2 “Smart City Project in Aguas, Brazil”

The main objective of the second project was to transform the city of Aguas into a digital hub with technology to improve public services, while serving as a showroom to generate business opportunities for service MNEs. The project included a range of applications such as smart parking, smart street lighting and e-government platforms. The major actors from the business side were Telefonica/Vivo, Ericsson, Huawei and ISPM. Ericsson and Telefonica/Vivo have worked together, as mentioned in the previous section. Huawei is a Chinese company specialising in telecommunication equipment and services, while ISPM is a Brazilian company specialising in the development of IoT (internet of things) platforms in 4G technologies. Other actors included the city’s mayor, public officials and two NGOs named ‘Vanzolini’ and ‘Telefonica Foundation’. The project received substantial local media coverage when implemented in 2015 and also received international visibility among the entrepreneurial community with recognition as being an innovative project by TM Catalyst Forum. The planning and implementation phases are described below.

3.3.1 Planning Phase

As project leader, Telefonica/Vivo made a proposal to the city mayor in 2014 to expand its technological solutions in alignment with the city’s social needs. With about 3000 inhabitants and a high level of those on the human development index, the city was chosen by the companies due to the low level of investment required. Telefonica/Vivo’s president asserted that: “A pilot project serves as a laboratory for the creation of public-private partnerships (PPPs), mainly in more populated municipalities.” Through a partnership agreement with the city mayor, but not as a PPP, and with an initial investment of over 510 million USD Telefonica/Vivo started replacing the old telephone exchange at different points in the city. To provide the whole solution it was also necessary to involve a constellation of other business partners (see Fig. 3). Another investment made by Telefonica/Vivo was in relation to its human resources. A team of managers with expertise in relationship development with public officials and mayors was organised. Teams not only included project managers, but also public relation managers, with the responsibility to monitor and reduce any negative impact of the project in the local media.

The Head of innovation at Telefonica/Vivo highlighted that: “We decided to work in areas where the mayor informed us that the city had problems to solve.” However, despite the innovative idea, Telefonica/Vivo had difficulties being understood by the public officials. The tourism secretary was one of the few public servants who understood the idea. According to him, the lack of technological knowledge, especially in small municipalities in Brazil, was a serious issue: “Some of them are illiterate with respect to technology. They did not know how the technology could help them.”

The tourism secretary was an important partner for the companies. He became the coordinator from the city side and was interested in the potential visibility that the project would bring to the city. Committed to the project idea, he started facilitating the project development by removing some practical obstacles, such as license requirements. But he also placed demands on the firms. For instance, when the companies wanted to charge for some of their services, he stressed: “You are multinationals and should better assess the city’s value. We have much more to lose than you, we are a small town. Both can win but if not, you will leave while the city stays. After presenting my arguments, companies understood the rules and values.” Once the project was understood from both sides the next phase was the process of implementing the technology.

3.3.2 Implementation Phase

Telefonica/Vivo’s team was formed of 15–20 people and consisted of technicians, developers, managers, etc., who gave support to both the city and the business partners. Although the technology had previously been developed by the firms, it required adjustment in the context of the city. The tourism secretary was interested in the smart parking solution, because the city doubles in population during weekends as it is famous for its water, which is used for hydrotherapy purposes. Another challenge was to reduce the electricity costs. Thus, Ericsson was chosen by Telefonica/Vivo to participate in developing parking and lighting solutions.

By equipping 500 parking spaces with sensors detecting whether the parking spaces were vacant or not, the intention was to cut down on traffic congestion and carbon emissions. The main challenge, however, was that most of the technology were developed for indoor (inside buildings) environments. According to the innovation manager at Telefonica/Vivo, this was the first time it had been done outdoors. The tourism secretary pointed out some of the problems, one being that the sensors of the smart parking solution only worked some of the time, which created frustration among the citizens. He affirmed that: “We were frequently asked by citizens for the reasons why the sensors worked well when the project was launched but not anymore. I felt a bit disappointed too.”

Another technology that did not work properly for two consecutive weeks was the smart lighting. However, despite being informed about the problem, both Ericsson and Telefonica/Vivo made a low commitment to solve it, affirmed the secretary. A critical episode was when a major holiday was approaching, and the city was expecting to receive 10,000 visitors. When asked how the problem was solved the secretary said: “I was furious. It was a problem for me to have the public park completely dark. I said to people at the companies: This is not my problem. It is your problem Telefonica/Vivo. Should I inform the media how things are working here? After that, the problem was solved.”

To enhance security in the city, 15 surveillance cameras were provided by Huawei to monitor the city. The project was important for Huawei as the brand was not yet well known in Brazil. The solution manager highlighted that “Being part of this project allowed us to show how the technology can be applied in real situations. It is our showroom.” But interactions were challenging, and the implementation was a learning process. According to the solution manager at Huawei, “We didn’t have any practical experience in cities. For example, it is easy to identify places where the cameras could be installed, but we did not think about a camera above the city bus terminal, which required electricity and connectivity.” Another difficulty Huawei faced within city hall was after the installation of its equipment. Managers expected that public officials would use them. The manager said to the mayor: “We gave you the technology. You need to have a team to operate it, but the mayor did not know who could operate them. After that we realised that staff training should be part of any project.”

Despite the challenge, when asked about the importance of such projects for Huawei’s local performance, the senior solution manager explained that: “Participating in the first smart city project in Brazil creates branding for the company, but also showcases the technology.” According to him, it is much easier to convince a client when it is possible to show how things function in practice, i.e., show how to solve a problem in a city setting. He claimed that the pilot project has generated several new business opportunities—around 20 different municipalities, i.e., mayors, have shown interest, and deals with mayors are in the process of negotiation. For the company, “Showing the technology functioning in practice in a city has increased Huawei’s market legitimacy and enhanced the message that we can deliver such a solution to any city in the world.”

Another partner invited by Telefonica/Vivo was ISPM. It had the responsibility for the maintenance of 400 remote solutions used across the health and education sectors. In addition, ISPM was in charge of integrating all services into its IoT platform. The company also develops digital application solutions in the health service, for example the scheduling of appointments and remote monitoring of clinical symptoms of patients via the internet. Furthermore, two apps have been developed which enable more direct engagement between citizens and the local government. According to the tourism secretary, such service apps are improving the public service image. For instance, complaints through social media, such as Facebook, which harm the image of the public authority on a broad scale, have been reduced. According to the secretary: “Citizens prefer to complain directly to the city hall because they are starting to have more trust in our response and problem solving.” In education, Telefonica/Vivo has donated 410 netbooks and tablets to students in the city’s public schools. The service allows access to digital content (e.g., books, videos and news). As part of the project, the Telefonica Foundation and Vanzolini Foundation together, have trained school teachers to use the new interactive platform. Telefonica Foundation’s coordinator highlighted that: “Having a foundation is strategically important, not only for showing corporate social responsibility, but also serving as a tool to engage with the public authorities.” Furthermore, because of several initiatives to improve citizens’ community life, the Telefonica Foundation has been able to reduce conflicts, and even avoid punishment from regulators of the Telefonica Group.

When asked about the importance of the project for the city, as well as the relationship between the private and public sector, the secretary highlighted that the cooperation had been very good. For example, “Ericsson has helped us to reduce our electricity bill by 35%. Bulbs send a message to us when they are close to expiring.” However, there has been a negative link between Telefonica/Vivo’s image with respect to the image of the city hall. He highlights that: “Citizens complain that they live in a smart city, but with poor connectivity at home. The poor service was perceived as a failure of city hall, although it was out of our control, and the scope of the project.” Figure 3 displays the project network view. Represented in black and dashed grey are the business actors while in striped black and grey are the political and non-profit actors respectively. In black are the service MNEs, which are the focus of our analysis.

4 Case Analysis

This section analyses the cooperative effort between service MNEs and socio-political actors in projects for smart cities. Similarities and differences between the cases are examined in connection to the main theoretical concepts of knowledge, commitment and legitimacy as important elements for cooperation. MNEs’ cross border political strategies to leverage business opportunities are also highlighted. Table 3 summarises the factors influencing the competitive market position of MNEs with socio-political interactions.

The MNEs in both cases were seeking to gain full advantage of the opportunities, with regard to the technology developed. To execute strategies effectively, they relied on networks consisting of multitudes of actors to create innovation and commercialisation of a new concept of products/services, named ‘the smart city concept’. The projects were used intentionally as a means to create the market for companies in Brazil and then expand the concept into Latin America. The most interesting strategy used by the firms was to successfully make a link between their profit goals whilst having a social purpose. Both projects had a societal need to fulfil and that was the starting point that united the service MNEs and socio-political actors, more precisely, public officials and NGOs, in a cooperative form of interaction (see Figs. 2 and 3). Projects with a social purpose, like those described in this study, created favourable contextual conditions for both social and economic welfare.

Interdependence and collective effort, moderated by the expectations for future benefits, helped to accommodate all different interest groups (see Table 3). While politicians could view such a project as a means to increase visibility and legitimacy in the eyes of citizens’, MNEs strategically used the projects as a marketing tool for promoting brand awareness, market creation and expansion, as well as strengthening their competitive position. For that, it was necessary to build political relationships with local business partners and NGOs in order to gain support and acceptance for their technologies, as well as to achieve market legitimacy.

4.1 Knowledge and Cooperation

One of the key aspects observed from the cases is that cooperation helped the MNEs to access an important political asset, i.e., socio-political experiential knowledge. Through the cooperation, service MNEs acquired knowledge with respect to the socio-political context that was beyond their business scope. Understanding the context was essential for the adaptation of the technology, and the development of services, to meet the city’s needs. As Hadjikhani et al. (2008) suggest, relationships between business and socio-political actors have a mutual nature, but contrary to business-to-business relationships, socio-political interactions are anchored on social and political values, rather than on pure economic value. Hence, in socio-political interactions, a source of competitive advantage lies in the ability to comprehend what the political interests are and turn such interests into support to facilitate business operations in foreign emerging markets (see Table 3). Therefore, managing relationships with public officials is rather complex and requires an approach that differs from the traditional market-based approach.

In this study, companies’ access to market knowledge, social context and political knowledge is associated with two dimensions: technological and relational. The cases illustrate that technologies developed through the recombination of actors’ resources were the result of socio-political interactions. Thus, technological and relational aspects are intertwined. One interesting aspect observed in these cases, was that non-business actors became channels for ideas to companies. In case 1, the idea of having real time bus fleet management came from the non-business actors URBS and ICI, and the business firms benefited from it. As a consequence, Ericsson and Telefonica/Vivo have incorporated a public transport service into their global business portfolio. In case 2, MNEs were informed about societal problems and the needs of the city. Apps developed for health issues were a result of feedback from citizens. Furthermore, companies were allowed by the municipality to use the city as a showroom and also as a laboratory for learning and incremental development of their technologies.

The relationships developed between MNEs and socio-political actors created knowledge synergies that enhanced the integration of actors’ resources, generating mutual benefits. In addition, such support strengthened the companies’ position as service solution providers in an emerging concept, i.e., ‘smart cities’. Moreover, both cases illustrate that successful projects create connections among actors, build trust, enhance credibility and, depending on its scope, gain endorsement and receptiveness by public officials and also the host government. The difference observed between the cases is that in case 1, public officials were knowledgeable about the technology while in case 2, public officials were not familiar with the technology and the companies then faced more resistance due to the poor understanding of the potential benefits that it could generate.

Concerning the relationship dimension, discrepancies across the cases were larger in comparison to the technological dimension. Variation was observed in respect to coordination and actors’ expectations. Tensions, misunderstandings, as well as conflicts, emerged in both cases. However, case 1 was rather smooth in comparison to case 2. Sources of tension and conflicts were linked to technical problems, and success was strongly linked to URBS’s ability to coordinate the project with companies, i.e., the combination of URBS’s local market knowledge, its commitment and previous relational knowledge concerning business actors facilitated cooperation. For the MNEs studied in case 1, their long term established presence in the host country and relationship competence, contributed to the socio-political interaction. Another important aspect is the MNEs’ marketing knowledge, which helped to promote the project nationally and overseas.

In contrast, in case 2, conflicts, misunderstandings and even lack of knowledge, were observed with regard to the socio-political values. An example was the companies’ intentions to charge for services, while at the same time using the city to promote themselves. Such behaviour created discomfort at city hall and showed how the business firms did not understand vital differences between the business arena and the socio-political arena. In other words, the MNEs’ behaviour was more linked to business profits and short-term interests rather than in creating a new market and long-term relationships.

One possible explanation for the differences between the two cases is that in case 1 the non-business actors were used to participating in large projects. Hence, they were used to project management and B2B relationships which companies are more familiar with. This created a synergy effect when values and organizational practices intersected, which facilitated cooperation. In contrast, case 2 illustrates the public officials’ lack of knowledge in respect to the technology, and lack of experience in dealing with MNEs, i.e., the relational dimension. It is likely that in a small town, such as in case 2, project management with MNEs is less common.

4.2 Commitment and Cooperation

Commitment was observed with regards to both technological and relational dimensions. In the two cases, technological adaptation and service development improved public services. The difference observed is that in case 1 all actors were interested in the success of the project, despite the lack of financial resource commitment from the business actors. In case 2, however, commitment was observed by the firms’ investment in technology, as well as in relationship development. In case 2, despite the lack of financial resource commitment from the political actors, efforts were noticeable in a more relational aspect. Examples include the support obtained from public officials to the MNEs to reduce bureaucracy in order to speed up the project’s development (see Table 3). All MNEs had a unit committed to develop relationships, and understand what the agenda of the public authorities was. Another difference observed between the cases was related to the role of the NGOs. In case 1, the NGOs did not contribute with any financial resources, but rather gave local knowledge, while in case 2, financial contributions were observed by the NGOs donating part of the technology, such as tablets for the public schools.

Relationship commitment between the MNE executives and government officials is an important element for strengthening cooperative relationships and creating exchanges between actors. In volatile and uncertain business environments, such as emerging economies, firms are expected to rely more on personal ties. An interesting aspect of the firms’ relational commitment towards political actors in case 2, is the investment in business conferences. For example, Huawei organized, together with Telefonica, the event ‘Brazil Digital City Summit’ in Sao Paulo, to communicate to the market its technological know-how applicable to smart cities. The summit took place immediately after the launch of the smart city project and the main target audience were politicians and public officials working at different levels of government, since they are the main potential clients. Political leaders were not only invited to attend the summit, but some were also invited as guest speakers. The secretary for Science and Technology for social inclusion, talked at the summit about a PPP (Public-Private Partnership) between Huawei and MCTI (The ministry of science and technology) in another smart city project in Bahia State. Furthermore, diplomats from China were also invited as guest speakers at the event. When asked about the reasons for inviting diplomats, the senior manager at Huawei emphasised the increasing importance in the last decade of bilateral relationships between Brazil and China. He added that diplomats span boundaries, linking firms and public authorities. Despite having an annual global smart city summit, the event in Brazil seemed to be a local strategy for increasing visibility. Huawei knows that Brazil has numerous ongoing initiatives to adapt smart technologies, including international partnerships. Another strategy used by Telefonica/Vivo was to demonstrate its projects including the one described here, at the Smart City Expo World Congress that happens annually in Barcelona. The MNE aims to create a centre of global competences in designing smart cities.

When it comes to the Swedish MNE, Ericsson, the firm’s involvement in Curitiba (case 1) has resulted in further smart city initiatives involving the city mayor, other business partners, and research institutes from Sweden and Brazil. The cooperation is part of a bilateral agreement signed by the city’s mayor and the Swedish King, Carl XVI Gustaf. Swedish investment in Brazil started as early as the end of the 19th century, and Ericsson was a pioneer. So, compared to Huawei, Ericsson has had a long relationship with the country, as it has been present in Brazil for almost a century. It is important to highlight the MNEs ability to cooperate, and manage the societal and political demands. The ability to satisfy such demands also created room for influencing the institutional environment. ICT technologies, in application to cities, are a new service in both emerging and developed economies. In Brazil, there is not yet any regulation for such technologies, and recently (February 2017) the government made a public consultation with regards to the ‘smart city concept’. For Ericsson the project has been also relevant, for instance, another municipality that will use Ericsson’s Smart Lighting solution is Sao Jose dos Campos, also located in Sao Paulo state. Therefore, involvement in pilot projects in this area is a promising strategy. While political actors become acquainted with new technologies, companies may help to design a regulatory framework for pioneering technologies applied in cities. Hence, firms’ political behaviour in emerging markets is not limited to lobbying activities, but can also be connected with what Elg et al. (2008) refer to as other relevant activities, for instance projects for a social purpose, as a means to get business profits and support from socio-political actors in a foreign market.

4.3 Legitimacy and Cooperation

In addition to knowledge and commitment, legitimacy was another important concept that emerged from the data and explains part of the successful cooperation. It is important to stress, however, that while business legitimacy is primarily concerned with the evaluation of connected suppliers and customers, political legitimacy relies on how firms and citizens perceive the actions of political actors. Gains in social welfare have been emphasised in political science as important tools for increasing public trust. In this study, legitimacy is analysed in a business and a political dimension. Both cases show that improving public services using new technologies and services is an important ingredient for building and enhancing political legitimacy. For example, the project developed in case 1 has been heavily used by the mayor in his political campaigns. Evidently, if a city mayor shows improvements in traffic and transportation through projects, this is likely to gain citizens’ attention, which can turn into public votes. For the business actors the project improved market legitimacy with regard to their technological expertise, since it was recognised by UNFCCC as an innovative solution, providing international visibility for the firms involved. An increase in market legitimacy was also observed from society and the people who use/will use these technologies.

In case 2, the project improved political legitimacy for the political actors and market legitimacy for the business actors. For example, the ‘app’ through which citizens can contact city hall directly has helped to increase trust in the public service, and consequently improved the city’s political image. Overall, the cases exemplify situations when business, political and societal interests intersect. The incentive of winning elections keeps politicians looking for projects that have high visibility with voters. ICT projects with the potential for community development, and improvement of government efficiency, not least in emerging economies with limited public investment, will leverage government attention and support for the MNEs that develop such technologies. Achieving legitimacy can be considered a strategic goal for an MNE, and an important step towards counterbalancing the liability of outsidership (Johanson and Vahlne 2009). For the studied firms, the combined aspects of their technological know-how, commitment to adapt their technology, as well as their learning process of understanding the social and political values, enhanced the MNE’s competitive local market position.

Relating back to the investments in business conferences as discussed in the previous section, there is a clear difference in terms of legitimacy between Ericsson and Huawei. Huawei’s senior manager stressed that the Chinese company is still not well known, even given its recent presence, in the Brazilian market, and that to build legitimacy they must increase commitment by relying on important boundary spanners such as—but not limited to—diplomacy, to build brand acceptance in the local market. Yet, strengthening cooperative relationships with social and political actors is helping Huawei’s competitive position, since it created support for the brand’s acceptance. Therefore, the lack of embeddedness and deficit in legitimacy is an additional obstacle for the Chinese subsidiary. This is in line with Eden and Miller (2004), who stress that firms engaging in an institutionally different host market are under pressure to gain social acceptance for survival. An example of increased legitimacy is Ericsson’s expansion of its four-year partnership with the municipality of Sao Jose dos Campos. The goal is the management of an emergency response system comprising 500 connected cameras, software systems, and 205 km of fibre optic cables. The partnership signed in 2016 includes Ericsson’s first contract to manage services related to smart city, within the public safety sector in Latin America. The new advancement of the partnership will have support from city hall, through the Technology Park located in the municipality. The Minister of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication, said: “Ericsson is a reference in terms of the means of development in the country and the world, as well as in improving quality of life. This agreement gives us all the opportunity to absorb knowledge, especially in the area of public safety. Now, we will rely heavily on this platform and take advantage of Ericsson’s knowledge to bring more security to all corners of Brazil” (Ericsson Homepage 2018).

An interesting aspect observed is the strategy of Telefonica/Vivo. In contrast to the other partners, the company uses its non-profit foundation to enhance market legitimacy, gain market knowledge and get involved in different types of interaction with government and public officials. To achieve legitimacy, the foundation promotes several initiatives to improve citizens’ lives in several municipalities within the country, and in other Latin America countries. With a non-profit focus, the foundation in Brazil has reduced conflicts, and even penalties due to ‘poor connectivity’, from regulators of the Telefonica Group. Poor service created a delay in case 1 that temporarily affected the image of the city hall, and similarly in case 2, a negative effect was observed with regard to the image of the city hall. Citizens’ dissatisfaction and frustration at living in a smart city, but having a poor internet connection, created citizens’ expectations that the problem should immediately be solved by city hall.

Further analysis of the relationships shows that legitimacy is a critical dimension, but also a relatively complicated one. The complexity of this dimension is that it is strongly connected to credibility and trust. On one hand, the project brought services that benefited society, but lack of business legitimacy in certain areas that were not directly related to the project reduced the benefit generated. This affected the project’s image and firm’s competitive position within the network. Therefore, legitimacy in this case can have a moderating effect on cooperation, knowledge, commitment and companies’ competitive position. It is important to note that legitimacy will change the impact of actors’ perception within the network with regard to willingness to cooperate, to share and acquire knowledge, as well as to commit to the relationship. Despite the deficit of legitimacy of some of the business actors, the net value of legitimacy was superior to the costs associated with the deficit of legitimacy. Such a situation also has implications for business to business relationships, since partners will assess and be willing to cooperate with others that not only enjoy legitimacy in the local market, but also have a potential to reinforce, within the network, the legitimacy of the other partners.

In addition to knowledge, commitment and legitimacy discussed above, cooperation with political actors can create new business opportunities. Not least, the use of new technologies can generate several benefits, for instance cost reduction, an improvement in the efficiency of public services, and transparency. Having government as earlier users can help companies to speed up the technological adoption on a broad scale, as Zanella et al. (2014) state. Another interesting aspect is that interaction with public officials constitutes a valuable resource since they are knowledgeable about what the needs of the society are. The exchange of ideas between MNEs and public officials thus assist companies to design their technology towards societal issues, which can generate public approval and political support.

Case 1 illustrates how the firms through the cooperation, learned how to interact with the public sector and how to gain access to local market information, as well as understanding public sector demands and needs. This type of cooperation is hard for other firms to copy and constitutes, thus, a source of competitive advantage. Ericsson later replicated the project described in case 1, with some adaptation to the local market, in Serbia, while Dataprom replicated it in Colombia. In both markets the public sector was in charge of the project. In case 2, such a strategy to create a project addressing a societal problem was a means, through cooperation, of enhancing both business and political legitimacy, while enhancing competitiveness (see Table 3). Thus, the importance of cooperation for competing for the business actors is clear. This strategy worked well, and the MNEs involved stressed that the project had opened a communication channel with the federal government, and that public officials at the top of the hierarchy were interested to know more about smart city technologies.

5 Conclusion

The theoretical view developed in this paper shows how actors who belong to different systems and have different legitimate grounds, can cooperate to achieve mutual gains. While the level of involvement in business activities explains the process of cooperation and knowledge building for technological and social adaptation, the process of commitment in the non-business market is identified as a variable, ranging from adaptation to influential behaviour, that satisfies the needs of society (Hadjikhani and Ghauri 2001). The paper stands on the view of researchers like Marquina and Morales (2012), that management of the non-business environment is a key competitive marketing strategy that influences market image and success in entry and expansion in foreign markets (Ghauri et al. 2012). Hence, the study supports the argument that competitive positioning holds the mechanism of management of three parallel interrelated processes of business and socio-political actors (Hadjikhani et al. 2016). Service MNCs in their attempt to strengthen their competitive position have to manage socio-political relationships that are essential and supplement their business activities.

Relating to the view of heterogeneity in services and classification scheme (Litteljohn et al. 2007), and the complications in employing views from manufacturing firms’ studies, this paper presented two object-based projects. Based on business network theory, we proposed a theoretical view on competitive behaviour, by applying the four interrelated concepts: knowledge, commitment, legitimacy and cooperation. The process of increasing knowledge and commitments, and the will for cooperation, is recognized as necessary for reaching diversified goals of different parties. Despite belonging to different systems and having diversified goals, the actors cooperate to reach mutual benefits. It can be concluded that the more political and social knowledge, as well as commitment, the more legitimacy an MNE may gain, and the more specific support it can receive from the social and political actors. On the other hand, a low level of political knowledge and commitment leads to low levels of cooperation, and the MNE will perceive the relationship as coercive, weakening the legitimacy and competitive position.

A further conclusion is that as an outcome of idiosyncratic relationships, the commitments in business, political and social arenas diffuse and affect the relationships in each area, as illustrated by Fig. 4. The higher the ‘pure’ business commitment, the greater the firm’s legitimacy among political and social actors in foreign markets, and the more legitimacy the firm and political units will gain. The higher the influence, the more privileged the firm is in its business activities. Interestingly, as the cases illustrate, despite a variety of gains in terms of knowledge and legitimacy, all parties acted to preserve a kind of mutuality in not harming the other parties.

Furthermore, distinguishing socio-political relationships from business relationships leads to another conclusion which concerns the aspect of political agenda. The two cases had different agendas, involving different units and differences in their network structure. To become involved in a project, the management function of the service MNE must generate a proposal which is grounded on the need of the society, as well as political units. The uniqueness of this agenda can be explained as the management’s ability to incorporate their business resources into the needs of the political actors and others in the political system. The key implication is that, extensive public-private networking is still needed, even when MNEs enjoy an established position in a foreign market. Hence, from a business point of view, public-private cooperation is a source of competitive advantage.

The network defined for this study is a set of actors–MNEs from Sweden, Brazil, China and Spain, as well as local government, public officials, society, NGOs and several other intermediaries, including diplomats from China and Sweden–linked to one another in the development of object-based services. The interaction among these actors constitutes a loose network. Contrary to an industrial network (Ford 1990) the network in this study is contingent upon a situation in which the position of political actors is not stable, since the values of the connected actors are changing. In such networks, MNEs devote lots of time to finding out about the political actors’ positions, about the social needs of the people, newcomers and new ideas released in the media, and even about their competitors’ political activities. A commitment to new relationships, such as social relationships, is a way for managers to keep relationships alive.

Our study opens new doors for further research on how the four conceptual elements, in this loosely structured network, change in this process. Following suggestions of researchers like Ghauri and Firth (2009) the cases have provided knowledge on the behaviour of three interconnected actors. However, to enable generalisation, this study calls for new research, holding additional cases, as well as statistical measures, for validation of the theoretical views.

From a practical perspective, our results provide useful guidelines for practitioners. A managerial implication is that to manage such relationships, managers need to identify what norms, values and beliefs drive the actors involved, and how to manage when such norms and values intersect. For firms seeking growth opportunities, it is beneficial to understand that political skill is essential for building, maintaining, and using social networks. Identifying boundary spanners is very important when building legitimacy and creating new business opportunities. We conclude that in order to strengthen their competitive market position, service MNEs should: (a) approach people with diverse political influence, which can generate future business opportunities, (b) show genuine interest and commitment concerning societal needs, and find technologies that can help public authorities to solve societal problems, (c) try to bring benefits in terms of cost reductions for mayors, since emerging economies have limited budgets for urban development in comparison to developed economies; and finally (d) cultivate close relationships with mutual interests.

References

Benigno, G., & Fornaro, L. (2014). The financial resource curse. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 116(1), 58–86.

Boddewyn, J., & Doh, J. (2011). Global strategy and the collaboration of MNEs, NGOs, and governments for the provisioning of collective goods in emerging markets. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3–4), 345–361.

Business Source Complete (2018). https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/results?vid = 7&sid = bc163592-7498-4aaf-90f4-1fe85379780e%40sessionmgr4007&bquery = (Internationalization + AND + %22of%22 + AND + firms)&bdata = JmRiPWJ0aCZjbGkwPVJWJmNsdjA9WSZjbGkxPURUMSZjbHYxPTIwMTAwMS0yMDE4MDYmY2xpMj1QVDgzJmNsdjI9KFBUK0FjYWRlbWljK0pvdXJuYWwpJnR5cGU9MCZzaXRlPWVob3N0LWxpdmU%3d. Accessed 23 Aug 2018.

Choi, S., Jia, N., & Lu, J. (2014). The structure of political institutions and effectiveness of corporate political lobbying. Organization Science, 26(1), 158–179.

Clark, T., & Rajaratnam, D. (1999). International services: Perspectives at century’s end. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(4–5), 298–310.

Cosset, J.-C., & Roy, J. (1991). The determinants of country risk ratings. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(1), 135–142.

Crane, A., & Desmond, J. (2002). Societal marketing and morality. European Journal of Marketing, 36(5–6), 548–569.

Cui, L., & Jiang, F. (2012). State ownership effect on firms’ FDI ownership decisions under institutional pressure: A study of Chinese outward-investing firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(3), 264–284.

Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. (2004). Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. In M. A. Hitt & J. L. C. Cheng (Eds.), Theories of the multinational enterprise: diversity, complexity and relevance (pp. 187–221). Amsterdam: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Elg, U., Ghauri, P. N., & Schaumann, J. (2015). Internationalization through sociopolitical relationships: MNEs in India. Long Range Planning, 48(5), 334–345.

Elg, U., Ghauri, P., & Tarnovskaya, V. (2008). The role of networks and matching in market entry to emerging retail markets. International Marketing Review, 25(6), 674–699.

Ericsson Homepage (2018). https://www.ericsson.com/en/press-releases/latin-america/2017/2/brazilian-government-and-ericsson-join-forces-to-develop-public-safety-iot. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

Esteves, K., & Feldmann, P. R. (2016). Why Brazil does not innovate: A comparison among nations. RAI Revista de Administração e Inovação, 13(1), 29–38.

Ford, D. (1990). Understanding business market: interaction, relationships, networks. London: Academic Press.

Ford, D., Gadde, L. E., Håkansson, H., & Snehota, I. (2011). Chichester: Managing business relationships. Chichester: Wiley.

Forsgren, M., Holm, U., & Johanson, J. (2015). Knowledge, networks and power—The Uppsala School of International Business. In U. Holm, et al. (Eds.), Knowledge, networks and power (pp. 3–38). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ghauri, P., & Firth, R. (2009). The formalization of case study research in international business. Der Markt, 48(1–2), 29–40.

Ghauri, P., & Grønhaug, K. (2005). Research methods in business studies: A practical guide. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Ghauri, P., Hadjikhani, A., & Elg, U. (2012). The three pillars: Business, state and society: MNCs in emerging markets. In A. Hadjikhani, et al. (Eds.), Business, Society and Politics (Vol. 28, pp. 3–16). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Ghauri, P., & Park, B. (2012). The impact of turbulent events on knowledge acquisition. Management International Review, 52(2), 293–315.

Gibbert, M., Ruigrok, W., & Wicki, B. (2008). What passes as a rigorous case study? Strategic Management Journal, 29(13), 1465–1474.

Hadjikhani, A., & Johanson, J. (1996). Facing foreign market turbulence: Three Swedish multinationals in Iran. Journal of International Marketing, 4(4), 53–74.

Hadjikhani, A., Elg, U., & Ghauri, P. (2012). Business, society and politics: Multinationals in emerging markets. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Hadjikhani, A., & Ghauri, P. (2001). The behaviour of international firms in socio-political environments in the European Union. Journal of Business Research, 52(3), 263–275.

Hadjikhani, A., Lee, J. W., & Ghauri, P. (2008). Network view of MNCs’ socio-political behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61(9), 912–924.

Hadjikhani, A., Lee, J. W., & Park, S. (2016). Corporate social responsibility as a marketing strategy in foreign markets: the case of Korean MNCs in the Chinese electronics market. International Marketing Review, 33(4), 530–554.