Abstract

Cultured meat, i.e. meat produced in-vitro through the cultivation of animal stem cells, is a radical innovation that prepares to enter the market in the near future. It has the potential to substantially reduce the negative externalities of today’s meat production and consumption and pave the way for a more sustainable global food system. However, this potential can only be realized if cultured meat penetrates the mass-market, which renders consumer acceptance a critical bottleneck. Using structural equation modeling, the present paper investigates the role of hitherto neglected organizational factors (trustworthiness, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and extrinsic motives) as antecedents of consumer acceptance of cultured meat. To this end, a pre-post intervention design in terms of a two-part online questionnaire was used with the final sample consisting of 966 participants. We found that in addition to established antecedents on the product level, organizational trustworthiness and CSR have a significant influence on consumers’ willingness to buy cultured meat. The findings indicate that organizational factors matter for consumer acceptance of cultured meat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Today’s global food system leaves an enormous environmental footprint. A recent study in Nature Foods concludes that the global food system accounts for 35% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, with animal-based products being responsible for 57% of these outcomes (Xu et al. 2021). Given that a large portion of these emissions is generated by meat production (Poore and Nemecek 2018) and since the global demand for meat will continue to grow (Alexandratos and Bruinsma 2012), the negative external effects of the global food system are likely to magnify in the future.

A new direction to reduce the environmental footprint of the global food system is provided by cultured meat. Simply put, cultured meat is manufactured in-vitro, i.e. outside of a living animal through the use of animal stem cells and tissue-engineering techniques (Post 2012, 2014; Rischer et al. 2020). Notably, cultured meat has the potential to become a (nearly) perfect substitute for conventional meat (Datar et al. 2016; Treich 2021) as it goes along with the promise to have the same taste, appearance, and nutritional value as conventional meat (Djisalov et al. 2021; Post 2014). Moreover, it is anticipated that cultured meat products will be price-competitive with their conventional counterparts in the long run (Bryant 2020). However, as the in-vitro technology is still in an early phase of development, various technical and regulatory challenges need to be overcome for the large-scale production of cultured meat (Chen et al. 2022; Choudhury et al. 2020; Humbird 2021; Stephens et al. 2018). Accordingly, cultured meat has yet to prove in practice that it can replace conventionally produced meat.

Producing meat outside a living organism is a radical innovation that has the potential to promote sustainable development. A recent life-cycle assessment of cultured meat suggests that it will become the most environmentally friendly meat product if sustainable energy is used for its production (Sinke and Odegard 2021). Accordingly, a widespread integration of cultured meat into human diets can improve the sustainability performance of the global food system (Jairath et al. 2021). Under the assumption that cultured meat is real meat with (nearly) the same properties as conventional meat, its major advantage is the facilitation of a sustainable consumption “without sacrifice”. The possibility to consume sustainably without the need to give up on certain product features, such as taste and price, is a critical precondition for the promotion of more sustainable consumption habits (Luchs et al. 2012). However, widespread consumer acceptance of cultured meat cannot be taken for granted as consumers tend to reject innovations that radically break with familiar logics and habits (Heidenreich and Kraemer 2015; Heiskanen et al. 2007). This particularly applies to radical innovations in the food sector since the ingestion of new and unknown foods is potentially a direct danger to human health, leading consumers to be especially skeptical toward new foods (Pliner et al. 1993; Pliner and Salvy 2006).

Drawing on the example of a potential seller of cultured meat—a restaurant planning to serve cultured meat burgers—the present study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the factors that influence consumer acceptance of this food innovation. While consumer acceptance of cultured meat has begun to receive growing attention in academia in recent years (for an overview see Bryant and Barnett 2018, 2020; Pakseresht et al. 2022), existing studies on this topic are dominated by a product focus, i.e. consumer perceptions of product characteristics, such as taste (Rolland et al. 2020), naturalness (Wilks et al. 2021), nutritiousness (Gómez-Luciano et al. 2019), food safety (Bryant et al. 2020), and environmental performance (Palmieri et al. 2020), as well as a focus on consumers’ individual characteristics, such as demographics (Mancini and Antonioli 2019), frequency of meat consumption (Franceković et al. 2021), and attitudes toward new foods (Siegrist and Hartmann 2020). In contrast, the role of organizational factors, i.e. perceptions, evaluations, and cognitions about organizational attributes and actions (Brown and Dacin 1997), has been widely neglected thus far (for an exception, see Lin-Hi et al. 2022).

The present study is devoted to organizational factors in terms of organizational trustworthiness, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and the attribution of extrinsic motives as potential antecedents of consumer acceptance of cultured meat. We created a website of a fictitious restaurant that will offer cultured meat burgers and asked participants to evaluate its trustworthiness, corporate social responsibility, and the attributions of extrinsic motives. By investigating organizational trustworthiness and CSR, the study focuses on organizational factors that have been identified in the sustainability management literature as levers that enable companies to contribute to sustainable development (Gimenez and Tachizawa 2012; Hoejmose et al. 2012; Huq et al. 2014). For example, Meqdadi et al.’s (2017) findings suggest that trust plays an important role in spreading sustainability initiatives across supplier networks and the study by Orazalin (2020) indicates that companies with effective CSR strategies exhibit better environmental and social performance. Trust and CSR have also been demonstrated to be related to consumer acceptance of sustainable products. For instance, Konuk (2019) has found that trust in fair trade food labels has a positive effect on consumers’ willingness to buy these products and Nosi et al. (2020) have shown that there is a positive relationship between CSR image and consumer attitudes toward organic quinoa. Finally, the study integrates attributions of organizational motives. Given that cultured meat completely breaks with the traditional idea of meat production and is therefore perceived as unexpected and surprising (Van der Weele and Driessen 2019; Van der Weele and Tramper 2014), consumers are likely to engage in attributional reasoning and try to understand an organization’s motivation to sell cultured meat. Literature shows that stakeholders tend to be skeptical toward responsible organizational behaviors when they suspect extrinsic motives behind them, as demonstrated by studies on the introduction of an environmental innovation (Jahn et al. 2020) and on a corporate-initiated partnership with consumers to protect the environment (Romani et al. 2016).

Altogether, the present analysis of organizational factors builds on existing relationships in the sustainability management literature and asks the question of whether these factors also play a role in consumer acceptance of cultured meat. It can be argued that organizational factors are particularly relevant for consumer acceptance of cultured meat given its status as a radical innovation. From the perspective of individuals, a core characteristic of radical innovations is a high level of uncertainty regarding the consequences of their use, for example, in terms of the lack of reliable knowledge about the potentially functional and social disadvantages (Kleijnen et al. 2009; Ram and Sheth 1989; Rotolo et al. 2015).Footnote 1 In order to reduce uncertainty in purchasing decisions, consumers often rely on organizational factors (Brown 1998; Brown and Dacin 1997). Generally speaking, “what consumers know about a company can influence their reactions to the company’s products” (Brown and Dacin 1997, p. 79). In a nutshell: Organizational factors allow consumers to make inferences about unobservable product characteristics (Brown and Dacin 1997; Grabner-Kräuter 2002).

By investigating organizational trustworthiness, CSR, and the willingness to buy cultured meat, this study merges several topics that have been examined in the Journal of Business Economics: Sustainable consumption (Falke et al. 2022; Hankammer et al. 2021), consumer acceptance (Geiger et al. 2017; Kohl et al. 2018), diffusion of innovations (Schlichte et al. 2019; Stummer et al. 2021), and CSR (Graf and Wirl 2014; Neitzert and Petras 2022).

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: The next section outlines our research hypotheses, whereby in the first step, we focus on the antecedents on the product level in terms of product characteristics and emotional benefits, i.e. psychological advantages that consumers perceive from consumption. In the second step, we examine the role of the three organizational-level factors (trustworthiness, CSR, and extrinsic motives) in stimulating consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Section 3 provides the details on the design of the empirical study and in Sect. 4, we present the data analysis and results. The findings are discussed in Sect. 5. Section 6 describes the limitations of the study and Sect. 7 concludes the paper.

2 Hypotheses development

The market success of (new) products is closely related to the added value they provide to customers vis-à-vis incumbent products. In a nutshell: The higher the added value, the better consumers’ purchase-related attitudes. Customer value thereby derives from various sources and in the first place, from specific product characteristics, such as quality, user-friendliness, design, and added services (Gale 1994; Woodall 2003). Notably, customer value is a perceptual construct, which means that it is not solely derived from objective factors but is based on individuals’ subjective interpretations thereof (Woodruff 1997). Subjective assessments of product value are especially salient in the context of radical innovations since consumers’ knowledge about and experience with radical innovations is naturally limited.

In relation to food products, visual appearance, taste, texture, nutritional value, and food safety are among the most important product characteristics to generate customer value (Deliza et al. 2003; Shepherd 1990). Given that the first sensory contact with food is usually through the eyes (Wadhera and Capaldi-Phillips 2014), visual appearance of food plays a critical role in consumers’ decision making. Put simply, food that looks unappetizing puts consumers off, whereas food that looks appetizing “makes the mouth water”. In addition to visual impression, taste is a central factor in consumers’ food choice (Clark 1998; Liem and Russell 2019). The more preferred taste and the associated pleasure a product promises, the higher the chances for consumer acceptance. Even though the perception of this property seems to occur at a subconscious level, another significant factor involved in determining how people feel about food is its texture (Szczesniak and Kahn 1971). The optimum for each texture characteristic varies by food type (Jeltema et al. 2015), and it is especially appreciated when the texture is typical of the specific food, such as the juiciness of meat or fruit (Szczesniak and Kahn 1971). Since food consumption not only allows individuals to satisfy specific cravings, but also provides them with nutrients, nutritional value is another central product characteristic (Drichoutis et al. 2008; Kiesel et al. 2011). A good nutritional value allows consumers to comply with dietary guidelines and maintain a balanced diet. Finally, food safety is a fundamental aspect in food choice as food is directly absorbed into the body and thus, goes along with potentially harmful consequences for human health (Yeung and Morris 2001). In regard to new and unknown foods, food safety is particularly salient from consumers’ perspective due to the especially high (perceived) risk of getting sick or poisoned (Rozin 1976).

All of these product characteristics have already been found to affect the acceptance of cultured meat. For example, Tucker (2014) has shown that almost all study participants rejected cultured meat based on their sensory perceptions and that sensory appeal, such as appearance and texture, is crucial to consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Weinrich et al. (2020) have extended the findings on sensory expectations and found that consumers’ perceptions of bad taste of cultured meat negatively affected their intentions to try and consume the product. Moreover, Gómez-Luciano et al. (2019) have demonstrated that besides taste, the nutritional value of cultured meat is one of the most influential factors in consumer acceptance. In addition, the study by De Oliveira et al. (2021) has found that the most important attributes affecting consumer acceptance of cultured meat are safety and health aspects, such as the expected risk of zoonotic diseases and the expected food safety conditions. Accordingly, and in line with existing research, we put forth the following hypothesis:

H1: Positive perceptions of product characteristics (visual appearance, taste, texture, nutritional value, health and safety) have a positive impact on the acceptance of cultured meat.

Another source of customer added value on the product level are emotional benefits (Hartmann and Apaolaza Ibáñez 2006; Havlena and Holbrook 1986). Emotional benefits complement functional benefits and allow consumers to satisfy different psychological needs. Important emotional benefits of consuming a product include self-gratification (Kahneman and Knetsch 1992), social status enhancement (Griskevicius et al. 2010), and pride (Chang 2011). Notably, such emotional benefits differ from the previously described perceptions of product characteristics as they are embedded in consumers’ social contexts and are relevant for their social relationships.

Research demonstrates that emotional benefits are an important driver of sustainable consumption (Hartmann and Apaolaza Ibáñez 2006; Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez 2012). This is because sustainable products often go along with (perceptions of) disadvantages relative to conventional products, especially in regard to functional value attributes, such as price and (perceived) quality (Chang 2011; De Pelsmacker and Janssens 2007; Luchs et al. 2010). The realization of emotional benefits can compensate for the (perceived) loss in functional value and hence, promote the acceptance of a product with sustainability attributes. In the food sector, emotional benefits have been found to play an important role in the choice of sustainable products. For example, Apaolaza et al. (2018) have shown that the consumption of organic products is associated with increased emotional well-being, and Iweala et al. (2019) have demonstrated that choosing fair trade products evokes the feeling of warm glow. Since cultured meat has the power to become not only the most environmentally friendly meat product (Sinke and Odegard 2021) but also offers the potential to stop animal suffering (Hopkins and Dacey 2008), its consumption represents a form of prosocial behavior which, in turn, should provide consumers with emotional benefits and increase the perceived value of cultured meat. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived emotional benefits have a positive effect on the acceptance of cultured meat.

In light of consumers’ lack of knowledge about and experiences with radical innovations, radical innovations distinguish themselves through a high degree of uncertainty (O’Connor and Rice 2013; Rotolo et al. 2015). In this sense, radical innovations can be classified as credence goods whose market success hinges upon the question in how far consumers’ subjective feelings of uncertainty can be reduced. Since the possibilities to reduce uncertainty on the product level are naturally limited for radical innovations not yet available on the market, consumers search for information beyond the product itself (Grabner-Kräuter 2002; Maignan and Ferrell 2001). This means that secondary associations, i.e. associations not directly linked to the product, become relevant for purchasing decisions, including perceptions related to the organization (Keller 1993). Organizational factors offer a context for the evaluation of products and constitute a “basis for inferences about missing product attributes” (Brown and Dacin 1997, p. 80).

In this respect, organizational trustworthiness has been identified as a crucial factor for uncertainty reduction in previous research (Dirks and Ferrin 2001; Hart and Saunders 1997; Kramer 1999; Morgan and Hunt 1994). Especially for purchasing decisions, where information deficiencies are omnipresent, trust can complement or even replace the search for product-related information (Grabner-Kräuter 2002). Because perceived organizational trustworthiness signals a producer’s or seller’s benevolence, integrity, and competence (Mayer et al. 1995), it constitutes an important factor in the formation of product evaluations, especially when product performance is perceived as ambiguous (Gürhan-Canli and Batra 2004). Therefore, the uncertainty-reducing function of organizational trustworthiness can also promote the acceptance of radical innovations in the food sector (Siegrist et al. 2007). Hence, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H3: Organizational trustworthiness has a positive effect on the acceptance of cultured meat.

There is a broad academic debate on the question of how organizations can enhance their trustworthiness in the eyes of their stakeholders (e.g., Ben-Ner and Halldorsson 2010; Pirson and Malhotra 2011; Sirdeshmukh et al. 2002). Among the different factors that have been identified in this regard, CSR has been found to be a powerful means for trust building (Lin-Hi et al. 2015; Pivato et al. 2008; Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008). This is because CSR signals that an organization is concerned about the well-being of stakeholders and society as a whole (Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Siegel and Vitaliano 2007) and therewith reduces stakeholders’ perceived risk to be exploited in an exchange relationship (Lin-Hi et al. 2015). The positive link between CSR and trust from consumers’ perspective has been demonstrated by several empirical investigations (Lin et al. 2011; Pivato et al. 2008; Stanaland et al. 2011; Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008), leading Pivato et al. (2008, p. 3) to postulate that “the first result of a firm’s CSR activities is stakeholder trust.”

In addition, CSR positively influences consumers’ product evaluations and, for example, leads to enhanced perceptions of product value (Grabner-Kräuter et al. 2018; Mohr and Webb 2005) and higher levels of perceived product reliability and quality (Chernev and Blair 2015; Maignan and Ferrell 2001; McWilliams and Siegel 2001). Hence, CSR can function as a signal for unobservable product characteristics (Calveras and Ganuza 2018; Siegel and Vitaliano 2007; Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008) which, in turn, reduces perceived uncertainties and positively affects consumers’ purchase intentions (Grabner-Kräuter et al. 2018). Accordingly, it can be expected that CSR has a positive influence on consumer acceptance of radical innovations such as cultured meat, for which secondary associations are particularly important given the inability of consumers to fully judge their primary attributes. The link between CSR and the intention to buy or use an innovative product has received support from empirical investigations of genetically modified foods (Pino et al. 2016). Moreover, it has been shown that negative information about a cultured meat producer regarding its CSR performance has a negative effect on consumer acceptance of cultured meat (Rabl and Basso 2021). Therefore, we posit the following hypotheses:

H4i: CSR has a positive effect on organizational trustworthiness.

H4ii: CSR has a positive effect on the acceptance of cultured meat.

Based on the notion that “people care less about what others do than about why they do it” (Gilbert and Malone 1995, p. 21), research in the trust domain indicates that the attribution of motives to organizational actions affects organizational trustworthiness (McAllister 1995; Rempel et al. 1985). A categorization of organizational motives is provided by the differentiation between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motives refer to an organization’s motivation to contribute to the well-being of society, whereas extrinsic motives are self-interest-driven and include, for example, financial incentives and strategic considerations (Du et al. 2007; Jahn et al. 2020). Typically, it is argued that organizational behaviors motivated by extrinsic rationales are, by tendency, perceived as unethical and are therefore often not accepted by consumers (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Vlachos et al. 2009). This is because extrinsic attributions convey the impression that an organization lacks moral traits such as benevolence and integrity. Since these traits belong to the fundamental antecedents of trustworthiness (Mayer et al. 1995), their attribution to an organization diminishes its perceived trustworthiness. Indeed, the negative relationship between the attribution of extrinsic motives and organizational trustworthiness has received empirical support in previous studies (Terwel et al. 2009; Vlachos et al. 2009).

Likewise, research suggests that the attribution of motives to organizational activities affects consumers’ acceptance of their products. For example, studies have shown that the attribution of extrinsic motives to advertising activities, sponsorships, environmental innovations, and cause-related marketing activities affects outcomes such as brand attitudes, attitudes toward the company, organizational credibility, brand loyalty, and product evaluation (Jahn et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2020; Moosmayer and Fuljahn 2013; Woisetschläger et al. 2017), all of which are important promoters of consumers’ willingness to buy a product (Aaker 1991). Furthermore, studies in the context of CSR have established a direct relationship between the attribution of extrinsic motives and purchase intentions (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Ellen et al. 2006). Accordingly, we expect that the attribution of extrinsic motives for doing business in the cultured meat sector should decrease consumer acceptance of cultured meat and postulate the following hypotheses:

H5i: The attribution of extrinsic motives has a negative effect on organizational trustworthiness.

H5ii: The attribution of extrinsic motives has a negative effect on the acceptance of cultured meat.

3 Study design

3.1 Procedure

We deployed a pre-post intervention design in terms of a two-part online questionnaire. After participants completed the first part of the questionnaire, they were directed to a website that served as an intervention, whereupon the second part of the questionnaire followed. The pre-post design was chosen because it allowed us to observe the difference in consumer acceptance before and after the intervention, accounting for additional effects due to the presentation of organizational information. This approach has been applied in other empirical studies to investigate the impact of new variables (e.g., Braddy et al. 2008; Hornsey et al. 2021; Mariconda and Lurati 2015).

In the first part of the questionnaire, after giving informed consent, participants were provided with textual information and illustrations to ensure they had basic knowledge about cultured meat and knew the products that could be made from it (e.g., meatballs, sausages, and burgers). Subsequently, participants answered several questions about their general willingness to buy a cultured meat burger in an undefined restaurant, the burger’s perceived characteristics, and the emotional benefits of consuming it.

The second part of the survey involved an intervention with a subsequent questionnaire. For the intervention, participants were directed to a website of a fictitious burger restaurant planning to offer cultured meat burgers in the future (“Alice in Burgerland”, see Appendix 1). The website contained the restaurant’s menu, including current pricing for burgers, sides, and drinks, as well as the information that burgers with cultured meat would soon be offered at the same price as conventional burgers. In addition, the website informed participants about organizational figures (e.g., number of employees), the restaurant’s competencies (e.g., experiences in the industry), and its social engagement (e.g., planting trees). To ensure that participants spent sufficient time on the website to read all the relevant information, a minimum of 120 s had to pass—a value based on a pilot test – before the “Continue” button appeared and participants could proceed with the survey.

After viewing the website, participants were directed back to the survey to answer the second part of the questionnaire. Again, participants were asked about their willingness to buy a cultured meat burger, but this time under the condition that it was offered by “Alice in Burgerland”. In addition, participants were asked to evaluate “Alice in Burgerland” in terms of its trustworthiness, CSR performance, and the attribution of extrinsic motives for doing business in the cultured meat sector. Finally, an attention check took place, followed up by questions on demographic information.

3.2 Data collection and sampling

Data collection took place over a period of seven days in August 2021 with a sample from Germany recruited through a market research institute. Participants received a monetary compensation for completing the questionnaire fully and conscientiously. The survey was designed following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003) to account for common method bias, for instance, by ensuring that participants were guaranteed the anonymity of their responses.

In total, 1065 participants filled out the questionnaire. Several steps of data cleaning took place. First, all participants who failed to pass the attention check and/or interrupted the questionnaire temporarily were excluded from the dataset. Second, responses with more than 30% missing data as well as those with systematic response patterns were excluded. Third, a speeding check was conducted by sorting out those participants who took less than one third of the median time to fill out the questionnaire.

The final sample consisted of 966 participants of which 473 were male, 492 female, and one identified as diverse. The mean age was M = 45.46 (SD = 14.3). Marginal quotas for age and gender were chosen. The gender distribution as well as the average age of the final sample thus roughly corresponded to the distribution of the population in Germany, which consists of 49.3% men and 50.7% women (Statistisches Bundesamt 2019) and has an average age of 44.6 years (Statistisches Bundesamt 2021). In terms of education, there was a certain tendency toward higher education compared to the German population (Statistisches Bundesamt 2019). More specifically, 24.84% of the participants stated that they had completed a university degree and 17.29% indicated that their highest degree was a (specialized) university entrance qualification. Comparatively fewer participants indicated that they had completed vocational training (36.54%), had a secondary school leaving certificate (15.84%), a lower secondary school leaving certificate (4.97%) or no school leaving qualification (0.31%). Two participants (0.21%) did not provide information on this question. Of the final sample, 867 participants stated that they followed either an omnivorous (N = 646; 66.87%) or a flexitarian (N = 221; 22.88%) diet. The remaining 99 participants were either vegetarian (N = 52; 5.38%), pescetarian (N = 28; 2.90%), or vegan (N = 19; 1.97%). The distribution of the diet types in our sample roughly resembles the overall distribution of diet types in Germany. Specifically, there were only slightly more participants following an omnivorous diet and less participants following a flexitarian diet compared to recent dietary data with 62.7% omnivores and 27.3% flexitarians (Veganz Group AG 2021).

3.3 Measures

The questionnaire was written and presented in German. English items were translated according to typical procedures. All items, except the items for product characteristics, were rated on a 7-point Likert-scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Table 2 in Appendix 2 provides the measurement items used in this study.

Acceptance: In line with existing research on consumer acceptance (e.g., Mancini and Antonioli 2020; Siegrist et al. 2018), acceptance of cultured meat was operationalized in terms of willingness to buy and measured pre and post intervention. We used the scale from Lin-Hi et al. (2022) which is based on Fenko et al. (2016). A sample item pre-intervention is: “I would consider ordering a burger with cultured meat at a restaurant” and post-intervention: “I would consider ordering a burger with cultured meat at Alice in Burgerland”. Overall, the scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95–0.96.

Product characteristics: To assess participants’ perceptions of the properties of cultured meat, a 7-point bipolar scale with anchors appropriate to the respective item, such as “not at all good”—“very good” for taste, was used. The established seven-item scale on product characteristics by Saeed and Grunert (2014) served as a basis from which items suitable for meat were selected and extended by one item regarding appearance. The final scale assessed how “tasty”, “visually appealing”, “nutritious”, “juicy”, and “healthy” participants believed cultured meat would be. The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Emotional benefits: Emotional benefits of consuming cultured meat were operationalized through feelings of warm glow. In line with typical scales to measure warm glow (e.g., Boobalan et al. 2021; Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez 2012; Hartmann et al. 2017), a four-item scale related to increased animal welfare was constructed with items like: “Eating a burger with cultured meat would give me a feeling of personal satisfaction as I can hereby contribute to animal welfare”. The scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95.

Organizational trustworthiness: To measure consumers’ perceptions of organizational trustworthiness, a three-dimensional scale by Gefen and Straub (2004) was used. It is comprised of 10 items that measure organizational integrity (α = 0.91), ability (α = 0.92), and benevolence (α = 0.91). A sample item is: “I expect that Alice in Burgerland puts customers’ interests before their own”.

CSR: To assess perceived CSR, a German four-item scale from Lin-Hi et al. (2020) was used, which itself is based on a scale developed by Stanaland et al. (2011). A sample item is: “Alice in Burgerland is committed to well-defined ethics principles”. The scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Extrinsic motives: The extrinsic motives participants attributed to “Alice in Burgerland” were measured by an established scale from Swaen and Chumpitaz (2008). Participants were asked whether they thought the restaurant was announcing to sell cultured meat burgers because “this gives them good publicity”, because “this lets them increase profits”, and because “this gets them more customers”. The scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

Control variables: Given existing findings regarding the link between the acceptance of cultured meat and age (Palmieri et al. 2020), gender (Bryant and Dillard 2019), and diet type (Bryant et al. 2019a), these three factors served as control variables regarding the willingness to buy cultured meat. To control for dietary preferences, participants were given a choice of five typical diets (e.g., omnivore, vegetarian, etc.) which were then summarized into the dichotomous variable of meat-eater vs. non-meat-eater.

4 Data analysis and results

Data preparation and all analyses were conducted in RStudio 1.3.1093 using the R-package “lavaan” (Rosseel 2012). A structural equation model (SEM; see Fig. 1) was tested which has the advantage of jointly testing the factorial structure of the individual variables as well as the pathways proposed in the hypotheses. A robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR; e.g., Brown 2015) was applied to calculate fit indices robust to non-normality. Additionally, age, gender, and dietary type were entered as control variables.

For evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was deployed on a measurement model consisting solely of the latent factors and their respective indicators. The measurement model yielded a good fit with the data (χ2 = 1309.192 (499), p < 0.0001, χ2/df = 2.62, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.962, RMSEA = 0.041, SRMR = 0.054) as the fit measures surpassed the thresholds established in the literature (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). The standardized factor loadings were statistically significant and ranged from 0.667 to 0.972, supporting the assumption of convergent validity among the measures. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs was higher than 0.5, further indicating convergent validity (Bagozzi and Yi 1988). The distinctiveness of the assessed variables, i.e. discriminant validity, was demonstrated by using a confidence interval approach. For each pair of factors, an interval was constructed as the correlation of the two plus minus its standard error and then it was assessed whether the number 1 was included. As this was not the case for any of the factor pairs, discriminant validity could be assumed (Koufteros 1999; Marcoulides 1998). Subsequently, internal consistency was addressed by observing the composite reliabilities, which all exceeded the recommended value of 0.7 (Hair et al. 2019) (see Table 1).

4.1 Preliminary analyses

Before carrying out the main analyses, a one-sample t test was conducted which compared the mean value of willingness to buy cultured meat before (M = 4.33, SD = 1.7) and after (M = 4.72, SD = 1.76) the intervention. The difference between the two mean values was significant (t(966) = − 13.21, p < 0.0001) and the average willingness to buy cultured meat was higher after viewing the website. This finding is a first indication that consumer acceptance of cultured meat can be influenced by information about the corresponding organization.

We observed rather high correlations between some of our variables, in particular, between organizational trustworthiness and CSR, as well as between the subdimensions of organizational trustworthiness. This is not surprising given that large correlations between these variables are to be expected due to the nature of their mutual relationship as proposed by theory. However, the correlations we observed appeared to be high compared to the literature and thus, we had to assure that this would not interfere with our main analyses. Hence, we examined both the distinctiveness of our constructs and potential multicollinearity.

High correlations may indicate that the constructs being measured are not distinct from each other, i.e. that they are part of the same construct (Brown 2015). Although this is unlikely in our case, given that discriminant validity has been established and the proposed factorial structure has strong theoretical support, we nevertheless wanted to take a closer look at this possibility. We followed the approach of Leiter and Durup (1994) as well as McCrory and Layte (2012) and the methodological advice from Byrant et al. (1999) to test competing models to ensure construct distinctiveness. Specifically, we accounted for high correlations between the subdimensions of trustworthiness (see Table 1) by collapsing the items onto a single factor and comparing it to the initially proposed second-order model where the three dimensions were left as separate factors loading onto a higher organizational trustworthiness construct. Compared to the second-order model, the corrected chi-square worsened significantly when all items loaded onto a single factor (Δχ2SB = 108.85(3), p < 0.0001; Satorra and Bentler 2001). Since this means that the single factor model performs worse, we measured organizational trustworthiness with the initial second-order model.

Additionally, we considered the high correlation between CSR and trustworthiness (0.939; see Table 1). To assess whether the two constructs were distinctive, the initially proposed measurement model was compared to a single factor model in which CSR was regarded as a fourth sub-dimension of organizational trustworthiness. The single factor model yielded a worse fit (Δχ2SB = 3.12(5), p = 0.682; Satorra and Bentler 2001) and, hence, was not superior to the one where CSR and organizational trustworthiness were modelled as separate factors, which led us to stick to the initially proposed model.

High correlations may further indicate potential multicollinearity within the sample, which may cause problems in SEM calculation and affect hypothesis testing. In examining this further, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), a standard indicator for assessing multicollinearity (O’Brien 2007), for the predictor variables (VIFProduct = 2.33, VIFWarmGlow = 2.33, VIFTrust = 9.55, VIFCSR = 10.13, VIFMotives = 1.02, VIFWTBPre = 1.61). The VIFs of the two highly correlated variables in organizational trustworthiness and CSR fell around the acceptable threshold of 10 (Gareth et al. 2013; Vittinghoff et al. 2006). In addition, the literature points out that VIFs alone should not inform the decision to accept or reject a predictor as it has to be viewed contextually (O’Brien 2007). We surmise that multicollinearity was not a problem in our sample due to the following reasons: First, discriminant validity was present, which is a highly relevant indicator for judging multicollinearity in the context of SEM (e.g., Farooq 2016). Second, and in line with Grewal et al. (2004), we concluded that our model was robust to multicollinearity as we had a high R2, good reliability, and a large sample (see also Dagger and O’Brien 2010; Ehrgott et al. 2011).

4.2 Main analyses and results

The results of the structural model in which we estimated all path coefficients are shown in Fig. 1. Overall, the final model had a good fit with the data (χ2 = 1667.475(605), p < 0.0001, χ2/df = 2.76, CFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.954, RMSEA = 0.043, SRMR = 0.056). Moreover, the model accounted for R2 = 75% of variance in the pre-intervention exposure willingness to buy cultured meat and for R2 = 86.2% of variance in the post-intervention exposure willingness to buy cultured meat.

Generally, our indicated p values are based on one-tailed testing as we addressed directional research hypotheses (Cho and Abe 2013; Jones 1952).

In Hypothesis 1, we expected that positive perceptions of product characteristics would have a positive effect on the acceptance of cultured meat. Indeed, characteristics of cultured meat significantly predicted participants’ willingness to buy (β = 0.224, p < 0.0001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

In Hypothesis 2, we anticipated that perceived emotional benefits would have a positive influence on the acceptance of cultured meat. Indeed, feelings of warm glow as an operationalization of the emotional benefits of consuming cultured meat significantly predicted its acceptance (β = 0.664, p < 0.0001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

In Hypothesis 3, we postulated that organizational trustworthiness would have a positive influence on the acceptance of cultured meat. Organizational trustworthiness had a significant impact on the willingness to buy cultured meat in the post-intervention exposure (β = 0.141, p = 0.027). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

In Hypothesis 4i, we assumed that CSR has a positive effect on organizational trustworthiness and in Hypothesis 4ii, we postulated that CSR has a positive effect on cultured meat acceptance. To test these hypotheses, the direct effects of CSR were analyzed, which yielded significant direct impacts on trustworthiness (β = 0.945, p < 0.0001) and willingness to buy (β = 0.126, p = 0.045). Additionally, we observed a significant indirect effect of CSR on willingness to buy mediated by trustworthiness (β = 0.134, p = 0.027). To further test the indirect effect, we used the bootstrap approach (Hayes 2013; Shrout and Bolger 2002), whereby we bootstrapped 5000 samples using a maximum likelihood estimator to obtain confidence intervals for the indirect path estimates. As we only considered directional hypotheses, we followed Preacher et al. (2010) and computed 90% confidence intervals in order to assess one-tailed significance tests (α = 0.05). The CI for the indirect effect of CSR on willingness to buy did not include zero (β = 0.191, CI [0.022; 0.363]), supporting the previous indication that trustworthiness partially mediates the relationship between CSR and the acceptance of cultured meat. Therefore, Hypotheses 4i and 4ii were both supported.

In Hypothesis 5i, we argued that the attribution of extrinsic motives negatively affects organizational trustworthiness and in Hypothesis 5ii, we anticipated that the attribution of extrinsic motives negatively affects the acceptance of cultured meat. Analogously to Hypotheses 4i and 4ii, we tested the direct as well as mediated paths, and found that neither the direct pathway towards organizational trustworthiness (β = 0.019, p = 0.174) nor the direct (β = − 0.022, p = 0.112) or indirect pathway (β = 0.003, p = 0.200) towards willingness to buy cultured meat were significant. Likewise, the bootstrapped indirect path estimate did include zero (β = 0.004, CI [− 0.001; 0.017]). Hence, Hypothesis 5i as well as Hypothesis 5ii were not supported.

5 Discussion

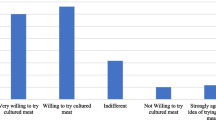

The present study was conducted in Germany. A few studies on consumer acceptance of cultured meat have been already carried out in this setting. For example, the first study in Germany has shown that the acceptance of cultured meat was moderate (Weinrich et al. 2020), with 57% of respondents reporting they would be willing to try it. A later study by Dupont et al. (2022) has found that 65% of German consumers were willing to try a cultured meat burger, and nearly 47% reported to be willing to replace conventional meat with cultured meat. A significantly higher willingness to consume cultured meat burgers was found among German children and adolescents when compared to other meat alternatives such as insect burgers (Dupont and Fiebelkorn 2020). In a cross-country comparison with French consumers, Germans expressed comparably high levels of enthusiasm toward cultured meat (Bryant et al. 2020), but in contrast, they showed relatively low acceptance of cultured meat relative to consumers from countries such as Mexico (Siegrist and Hartmann 2020). Finally, a recent study with German consumers has demonstrated that perceptions of organizational competence affect consumers’ willingness to buy cultured meat and startups and established companies have distinctive advantages in this regard (Lin-Hi et al. 2022). Finally, Moritz et al. (2022) have investigated a particular form of acceptance by focusing on political and policy actors in Germany.

5.1 Theoretical contribution

Given that the current research on consumer acceptance of cultured meat has been centered on product-related and consumer-related factors, its antecedents on the organizational level have been widely neglected. The lack of scholarly attention to organizational-level factors is also reflected in the fact that the existing debate on the acceptance of this food innovation has so far primarily taken place in food-related journals, such as Appetite (e.g., Bryant and Barnett 2019; Slade 2018; Wilks et al. 2021), Meat Science (e.g., Bryant et al. 2019b; Siegrist et al. 2018; Weinrich et al. 2020), and Food Quality and Preferences (e.g., Baum et al. 2021; Dupont and Fiebelkorn 2020; Gómez-Luciano et al. 2019). Thus, the innovation of cultured meat has not yet gained attention in management research.

The present paper makes several contributions to the literature on consumer acceptance of cultured meat and acceptance of innovations in general. First, it indicates that not only product-related factors function as antecedents of the acceptance of cultured meat but also second-order associations on the organizational level. Specifically, the results demonstrate that, in addition to product-related characteristics, higher levels of trustworthiness and perceptions of CSR can promote the acceptance of cultured meat. While existing research suggests that the positive relationship between trust and willingness to buy holds across different products and industries (Wang et al. 2022; Zaza and Erskine 2022; Zhuang et al. 2021), empirical findings on the link between CSR and buying intentions are inconclusive by tendency (Ali et al. 2010; Lee and Yoon 2018; Öberseder et al. 2014). Thus, the question arises as to what extent the paper’s finding on CSR are transferable to other contexts. We expect that our finding is not limited to cultured meat but also holds for other innovations. Given that consumers usually cannot fully assess the attributes of innovations when they are introduced to the market, innovations are typically surrounded by a considerable degree of acceptance-hindering uncertainty (Hoeffler 2003; Rogers 2003). Since CSR is a signal of a positive character of a company (Mohr and Webb 2005; Siegel and Vitaliano 2007), it reduces consumers’ perceptions of uncertainty and risk in buying decisions (Stanaland et al. 2011; Upadhye et al. 2019). In addition, it can be argued that the effect of CSR on acceptance should be stronger the higher the level of perceived uncertainty of an innovation. This view is echoed in the argument of Bhattacharya et al. (2021) who state that CSR is particularly relevant in higher-risk contexts. Accordingly, CSR should be especially potent in promoting the willingness to buy radical innovations given their high degree of novelty and the associated lack of familiarity.

Notably, we have collapsed commonly scrutinized product-related characteristics of cultured meat (visual appearance, taste, texture, nutritional value, and health and safety) onto one overarching factor which showed both a high reliability (α = 0.93) and a valid factorial structure within the overall measurement model. All tested attributes loaded highly (0.756–0.895) and significantly (p < 0.0001 for all loadings) onto this factor, suggesting that summarizing these variables into one scale is an approach that can be used in future research.

Second, the paper transfers existing findings from sustainability management literature to the domain of consumer acceptance of cultured meat. In this respect, the result that warm glow has a positive effect on the acceptance of cultured meat echoes the finding that emotional benefits matter in sustainable consumption (Boobalan et al. 2021; Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez 2012; Hartmann et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2020). This provides a first indication that the literature on sustainable consumption can be applied to the study of cultured meat. In addition, by examining the role of organizational trustworthiness and CSR, the paper illuminates on the factors that are commonly regarded as facilitators of the synergetic interplay between ecological, economic, and social goals. On the one hand, the positive effects of trustworthiness and CSR on consumer acceptance indicate that (sustainability) management literature provides a valuable framework for managerial research on cultured meat. On the other hand, a high correlation between organizational trustworthiness and CSR raises some questions. On a general level, the question arises as to whether different organizational factors engender distinct effects on consumer acceptance of cultured meat. The high correlation between organizational trustworthiness and CSR could be the effect of study participants’ inability to meaningfully distinguish between these organizational factors. One explanation for such a potential effect is provided by the novelty of cultured meat. In fact, almost two thirds of participants stated that they were not very familiar with this innovation before taking part in the study. The lack of familiarity with the main subject of this study could have instilled the fatigue effect among participants: Due to the high amount of new information about cultured meat, participants might have experienced a high cognitive load (e.g., Paas and Van Merriënboer 1994; Paas et al. 2003; Sweller 2011). Accordingly, they might have already depleted most of their cognitive resources by processing completely new information, so that they were unable to distinguish the organizational factors in terms of trustworthiness and CSR, but simply rated the organization based on an overall impression. Since both trustworthiness and CSR are positively valenced constructs, a fatigue effect could explain the high correlation between the two factors.

Third, the lack of support for the hypotheses that the attribution of extrinsic motives has an effect on organizational trustworthiness and on the acceptance of cultured meat differs from existing research. Several studies have shown that extrinsic motives are generally negatively associated with organizational trustworthiness (Terwel et al. 2009; Vlachos et al. 2009, 2010). However, researchers have already pointed out that a strict differentiation between extrinsic and intrinsic might be too coarse (Ellen et al. 2006). In this respect, it has been argued that, besides considering extrinsic motives as opportunistic, consumers might also recognize that an organization needs to make profits while contributing to social welfare, so that intrinsic and extrinsic motives do not have to be seen as strictly opposite constructs (Du et al. 2007; Myers et al. 2013). In fact, previous research has also shown that extrinsic motives are not generally perceived negatively if they are evaluated by differentiating between strategic and purely egoistic motives, i.e. by separating “legitimate” profit-orientation from “selfish” impulses (Ellen et al. 2006).

Notably, the present paper does not only contribute to research on consumer acceptance of cultured meat but also to the literature on the acceptance of innovations in general. In our study, we tested a framework that considers several predictors of consumer acceptance which offers important insights into the dynamics that are at play when presenting innovations to consumers. Specifically, we contribute to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms between CSR and consumer acceptance of innovations by introducing a three-dimensional construct of organizational trustworthiness as a mediator. In doing so, we answer existing calls to explore causal chains related to the interplay between CSR and consumer responses, for instance, in terms of responses to innovations (Deng and Xu 2017; Hofenk et al. 2019; Romani et al. 2013).

Another contribution is related to the effect of CSR on consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Existing research on the acceptance of innovations is rooted in an instrumental paradigm, whereby user’s assessment of personal advantages/disadvantages from adopting an innovation or technology forms the center of the debate (e.g., Davis 1989; Featherman and Pavlou 2003; Kulviwat et al. 2007). Our study advances existing literature by highlighting the relevance of the normative dimension in the formation of acceptance. Ethics-related variables, such as CSR perceptions, thereby might be especially relevant for the acceptance of radical innovations since radical innovations, as already argued, are characterized by a high degree of uncertainty (O’Connor and Rice 2013). Given that uncertainty perceptions are subjective and have a non-rational dimension (Cross 1998), reducing uncertainty via instrumental approaches is limited. At the same time, ethics are a trusted mechanism for people to cope with uncertainty (Francot 2014) which, in turn, renders ethics-related variables suitable for promoting the acceptance of radical innovations.

Furthermore, the paper contributes to the general research on the acceptance of innovations through the specific timing of data collection. Specifically, the data stems from an emerging innovation, i.e. an innovation that has not yet been introduced to the local market. The investigation of the potential antecedents of consumer acceptance of an innovation prior to its introduction offers the opportunity to assess the predictive validity of findings after the launch of the innovation at different points of its diffusion lifecycle. Such pre-post launch comparisons are helpful in evaluating the quality of current research approaches and hence lay the foundation for the development of more advanced approaches for the sake of making better predictions about future phenomena. Additionally, such comparisons would also allow for a better assessment of the contributions that the current conceptual frameworks in the sustainability management literature make to the diffusion of innovations for sustainable development.

Finally, our findings can be related to the debate on frameworks for sustainability management. CSR is a vehicle for companies to contribute to sustainable development (Behringer and Szegedi 2016; Herrmann 2004; Moon 2007), whereby a specific stream of research focuses on sustainability-oriented innovations (Bacinello et al. 2020; Shahzad et al. 2020; Yoon and Tello 2009). For example, studies show that CSR has a positive effect on firms’ adoption of sustainability-oriented innovations (e.g., Poussing 2019), sustainable innovation ambidexterity (e.g., Khan et al. 2021), and sustainability-oriented invention patents applications (Hong et al. 2020). In this debate, CSR is understood as a mechanism that enhances organizational capability to innovate for sustainability. Our study adds a new layer to this debate by demonstrating that CSR improves consumer acceptance of innovations. This perspective matters for CSR as an effective framework for fostering sustainability management since sustainability-oriented innovations can only exert their beneficial effects if they are accepted by consumers.

5.2 Practical contribution

Given that today’s meat production and consumption leave an immense environmental footprint, cultured meat holds the promise to improve the sustainability performance of the global food system (Balasubramanian et al. 2021; Rischer et al. 2020). In addition to the technical challenges that need to be overcome (Zhang et al. 2020), consumer acceptance is a critical bottleneck for this innovation to become a mass-market product and realize its sustainability potential (Post et al. 2020). Ultimately, consumer acceptance is a fundamental precondition for cultured meat to be able to penetrate the mass-market and replace the environmentally-unfriendly way of today’s meat production and consumption.

After in December, 2020 Singapore approved a cultured meat product for commercial sale as the first country in the world (Ives 2020), regulatory pathways to market are also beginning to emerge in the EU and US (Dent 2021). Already now, companies around the world are preparing to enter into the market for cultured meat. Accordingly, it is valuable to begin to devote systematic attention to the factors that promote consumer acceptance. In a nutshell and in more managerial terms: There is a need to better understand the drivers that promote the market success of cultured meat.

The findings of the present paper demonstrate that the acceptance of cultured meat is not only determined by product characteristics but also by organizational factors. At the same time, the results indicate that organizational factors can spill over to consumer attitudes toward innovative products. The link between organizational factors and product evaluations is particularly important for radical innovations as they are surrounded by a high degree of uncertainty. Organizational factors provide a possibility for consumers to cope with uncertainties which, in turn, can result in higher levels of consumer acceptance. In sum, it seems to be valuable for future marketing strategies for cultured meat to not only focus on the product-related factors but also on managing and highlighting positive organizational factors.

Finally, the study suggests that emotional benefits consumers derive from the consumption of cultured meat positively influence their acceptance of this product. Since higher customer value typically improves product sales, the promotion of emotional benefits is a potential lever to drive the market success of cultured meat. Based on this, it appears to be valuable to communicate the social relevance and the high sustainability potential of cultured meat in order to increase emotional benefits for consumers.

6 Limitations and future research

As with all research, the present study has some limitations. First, we examined the acceptance of cultured meat on the intentional and not on the behavioral level. Although intentions and behavior are related, they do not always go hand in hand (Sheeran and Webb 2016). In particular, in the field of sustainable consumption, the intention-behavior-gap is a widespread phenomenon (Carrington et al. 2014; ElHaffar et al. 2020). However, because cultured meat is presently not accessible to most consumers, it is not possible to measure consumers’ reactions towards cultured meat in terms of real buying behavior. Thus, as long as cultured meat is still in development phase, future research should use different methodological approaches to investigate consumer acceptance from different perspectives and therewith, prepare the ground for assessing real consumer behavior when cultured meat becomes available on supermarket shelves.

Second, given the high correlation between organizational trustworthiness and CSR, the distinctiveness of constructs and multicollinearity is another limitation of our study. However, the theoretical background of the model, discriminant validity, the testing of competing models, and the application of criteria from the literature suggest that our main analyses do not generally suffer from these issues. Nevertheless, no definite conclusion can be drawn whether trustworthiness and CSR affect the acceptance of cultured meat individually or in combination. Therefore, on the one hand, the findings show that organizational attributes are significant predictors of consumer acceptance of cultured meat. On the other hand, due to the high correlation, we cannot make any statements regarding the relative importance of either factor and the manner in which they interact with one another in this particular context. There are several ways to approach these limitations in future research: In order to ascertain whether the high correlation between CSR and trustworthiness was specific to our study or is a general phenomenon for the acceptance of cultured meat, the study could be replicated with a different sample. Furthermore, since experimental approaches avoid the problem of multicollinearity (Slinker and Glantz 1985), an experimental study could be carried out in which trustworthiness and CSR are manipulated both independently from each other and in combination, which would allow to examine the individual and combined influence of these variables on the acceptance of cultured meat. In general, more research is needed to understand the impact of organizational factors on consumer acceptance of cultured meat.

Third, in addition to the product characteristics we chose for our study, previous research has shown that other variables on the product level, such as perception of naturalness (e.g., Siegrist and Hartmann 2020; Siegrist and Sütterlin 2017; Siegrist et al. 2018; Wilks et al. 2021) and environmental friendliness (Circus and Robison 2019; Palmieri et al. 2020; Verbeke et al. 2015) influence consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Thus, we did not include all possible variables that may be of relevance when considering acceptance from a product characteristics perspective. Nonetheless, in our model, product characteristics are only relevant to acceptance in the pre-intervention stage. Since the impact of organizational factors on acceptance is tested in the post-intervention phase and since the correlations between product characteristics and organizational factors have not been modelled, their role as antecedents of acceptance is independent of the actual product characteristics chosen (or not chosen) in the present study. Nevertheless, future research on consumer acceptance of cultured meat would benefit from the inclusion of additional product characteristics-related variables, which could be gleaned from existing research on other food innovations.

Fourth, the study was conducted with a sample of German consumers. Yet, previous studies have demonstrated that regional and cultural variables have an effect on consumer acceptance of cultured meat (e.g., Bryant et al. 2019a; Bryant and Sanctorum 2021). In consequence, the generalizability of the study’s results is limited. Accordingly, it would be interesting to investigate potential effects of organizational factors in different cultural and regional settings. In this respect, a replication study in a cross-cultural setting could contribute to a better understanding of the role of organizational factors for consumer acceptance of cultured meat.

Fifth, our study participants were recruited by an online market research company. Although care was taken to generate data that as closely as possible represents the general population in terms of socio-demographic characteristics such as gender and age, a sampling bias cannot be ruled out. Participants in market research are mainly motivated by financial gains and may not be interested in the topic (Gómez-Luciano et al. 2019) which, in turn, could reduce their attention (Goodman et al. 2012). Against this backdrop, it seems to be valuable to replicate the study in future research with different samples.

7 Conclusion

When Winston Churchill famously claimed that we “shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium” in 1931, the idea of cultivating meat in a bioreactor seemed like pure science fiction. Yet, the vision of cultured meat is on the way of becoming reality. On the technical side, producing meat outside the living organism in a sustainable way is already possible on a small scale (Sinke and Odegard 2021) and the barriers to the scale-up of the production are being gradually removed. In light of this, the question of how cultured meat can be successfully introduced to the mass-market is becoming increasingly important.

The findings of the present study suggest that the acceptance of cultured meat is not only determined by the product itself but also by factors related to organizations. Hence, the study demonstrates that (sustainability) management research is able to contribute to consumer acceptance of cultured meat by revealing new antecedents. Yet, as mentioned before, management research has thus far neglected the innovation of cultured meat. Against the backdrop of the sustainability potential of cultured meat, it is to be hoped that this paper captures (sustainability) management scholars’ attention to this innovation.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

In the context of food innovations, uncertainty regarding health implications is particularly salient for consumers as foods are directly absorbed into the body (Yeung and Morris 2001).

References

Aaker DA (1991) Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. Free Press, New York, NY

Alexandratos N, Bruinsma J (2012) World agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 revision. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome

Ali I, Rehman KU, Yılmaz AK, Nazir S, Ali JF (2010) Effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer retention in the cellular industry of Pakistan. Afr J Bus Manag 4:475–485. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM.9000245

Apaolaza V, Hartmann P, D’Souza C, López CM (2018) Eat organic–Feel good? The relationship between organic food consumption, health concern and subjective wellbeing. Food Qual Prefer 63:51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.07.011

Bacinello E, Tontini G, Alberton A (2020) Influence of maturity on corporate social responsibility and sustainable innovation in business performance. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27:749–759. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1841

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16(74–94):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

Balasubramanian B, Liu W, Pushparaj K, Park S (2021) The epic of in vitro meat production—a fiction into reality. Foods 10:1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061395

Baum CM, Bröring S, Lagerkvist CJ (2021) Information, attitudes, and consumer evaluations of cultivated meat. Food Qual Prefer 92:104226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104226

Becker-Olsen KL, Cudmore BA, Hill RP (2006) The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J Bus Res 59:46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.01.001

Behringer K, Szegedi K (2016) The role of CSR in achieving sustainable development-theoretical approach. Eur Sci J 12:10–25

Ben-Ner A, Halldorsson F (2010) Trusting and trustworthiness: what are they, how to measure them, and what affects them. J Econ Psychol 31:64–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.001

Bhattacharya A, Good V, Sardashti H, Peloza J (2021) Beyond warm glow: the risk-mitigating effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR). J Bus Ethics 171:317–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04445-0

Bhattacharya CB, Korschun D, Sen S (2009) Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J Bus Ethics 85:257–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9730-3

Boobalan K, Nachimuthu GS, Sivakumaran B (2021) Understanding the psychological benefits in organic consumerism: an empirical exploration. Food Qual Prefer 87:104070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104070

Braddy PW, Meade AW, Kroustalis CM (2008) Online recruiting: the effects of organizational familiarity, website usability, and website attractiveness on viewers’ impressions of organizations. Comput Hum Behav 24:2992–3001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.05.005

Brown TA (2015) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press, New York, NY

Brown TJ (1998) Corporate associations in marketing: antecedents and consequences. Corp Reput Rev 1:215–233. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540045

Brown TJ, Dacin PA (1997) The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. J Mark 61:68–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100106

Bryant CJ (2020) Culture, meat, and cultured meat. J Anim Sci 98:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaa172

Bryant CJ, Anderson JE, Asher KE, Green C, Gasteratos K (2019a) Strategies for overcoming aversion to unnaturalness: the case of clean meat. Meat Sci 154:37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.04.004

Bryant C, Szejda K, Parekh N, Deshpande V, Tse B (2019b) A survey of consumer perceptions of plant-based and clean meat in the USA, India, and China. Front Sustain Food Syst 3:11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00011

Bryant C, Barnett J (2018) Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: a systematic review. Meat Sci 143:8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.04.008

Bryant CJ, Barnett JC (2019) What’s in a name? Consumer perceptions of in vitro meat under different names. Appetite 137:104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.02.021

Bryant C, Barnett J (2020) Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: an updated review (2018–2020). Appl Sci 10:5201. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10155201

Bryant C, Dillard C (2019) The impact of framing on acceptance of cultured meat. Front Nutr 6:103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00103

Bryant C, Sanctorum H (2021) Alternative proteins, evolving attitudes: comparing consumer attitudes to plant-based and cultured meat in Belgium in two consecutive years. Appetite 161:105161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105161

Bryant C, van Nek L, Rolland N (2020) European markets for cultured meat: a comparison of Germany and France. Foods 9:1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091152

Byrant FB, Yarnold PR, Michelson EA (1999) Statistical methodology: VIII. Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in emergency medicine research. Acad Emerg Med 6:54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00096.x

Calveras A, Ganuza JJ (2018) Corporate social responsibility and product quality. J Econ Manag Strategy 27:804–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12264

Carrington MJ, Neville BA, Whitwell GJ (2014) Lost in translation: exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. J Bus Res 67:2759–2767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.09.022

Chang C (2011) Feeling ambivalent about going green. J Advert 40:19–32. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367400402

Chen L, Guttieres D, Koenigsberg A, Barone PW, Sinskey AJ, Springs SL (2022) Large-scale cultured meat production: trends, challenges and promising biomanufacturing technologies. Biomaterials 280:121274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121274

Chernev A, Blair S (2015) Doing well by doing good: the benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. J Consum Res 41:1412–1425. https://doi.org/10.1086/680089

Cho HC, Abe S (2013) Is two-tailed testing for directional research hypotheses tests legitimate? J Bus Res 66:1261–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.023

Choudhury D, Tseng TW, Swartz E (2020) The business of cultured meat. Trends Biotechnol 38:573–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.02.012

Circus VE, Robison R (2019) Exploring perceptions of sustainable proteins and meat attachment. Br Food J 121:533–545. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2018-0025

Clark JE (1998) Taste and flavour: their importance in food choice and acceptance. Proc Nutr Soc 57:639–643. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19980093

Cross FB (1998) Facts and values in risk assessment. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 59:27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0951-8320(97)00116-6

Dagger TS, O’Brien TK (2010) Does experience matter? Differences in relationship benefits, satisfaction, trust, commitment and loyalty for novice and experienced service users. Eur J Mark 44:1528–1552. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011062952

Datar I, Kim E, d’Origny G (2016) New harvest. In: Donaldson B, Carter C (eds) The future of meat without animals, 1st edn. Rowman & Littlefield, London, pp 121–131

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13:319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Deliza R, Rosenthal A, Silva ALS (2003) Consumer attitude towards information on non conventional technology. Trends Food Sci Technol 14:43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-2244(02)00240-6

Deng X, Xu Y (2017) Consumers’ responses to corporate social responsibility initiatives: the mediating role of consumer–company identification. J Bus Ethics 142:515–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2742-x

Dent M (2021) Which country will be the next to approve cultured meat? IDTechEx. https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-article/which-country-will-be-the-next-to-approve-cultured-meat/23835. Accessed 30 Oct 2021

De Oliveira GA, Domingues CHDF, Borges JAR (2021) Analyzing the importance of attributes for Brazilian consumers to replace conventional beef with cultured meat. PLoS ONE 16:e0251432. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251432

De Pelsmacker P, Janssens W (2007) A model for fair trade buying behaviour: the role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. J Bus Ethics 75:361–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9259-2

Dirks KT, Ferrin DL (2001) The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ Sci 12:450–467. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640

Djisalov M, Knežić T, Podunavac I, Živojević K, Radonic V, Knežević NŽ, Bobrinetskiy I, Gadjanski I (2021) Cultivating multidisciplinarity: manufacturing and sensing challenges in cultured meat production. Biology 10:204. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10030204

Drichoutis AC, Lazaridis P, Nayga RM, Kapsokefalou M, Chryssochoidis G (2008) A theoretical and empirical investigation of nutritional label use. Europ J Health Econ 9:293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-007-0077-y

Du S, Bhattacharya CB, Sen S (2007) Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: the role of competitive positioning. Int J Res Mark 24:224–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2007.01.001

Dupont J, Fiebelkorn F (2020) Attitudes and acceptance of young people toward the consumption of insects and cultured meat in Germany. Food Qual Prefer 85:103983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103983

Dupont J, Harms T, Fiebelkorn F (2022) Acceptance of cultured meat in Germany—application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Foods 11:424. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030424

Ehrgott M, Reimann F, Kaufmann L, Carter CR (2011) Social sustainability in selecting emerging economy suppliers. J Bus Ethics 98:99–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0537-7

ElHaffar G, Durif F, Dubé L (2020) Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: a narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. J Clean Prod 275:122556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556

Ellen PS, Webb DJ, Mohr LA (2006) Building corporate associations: consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. J Acad Mark Sci 34:147–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070305284976

Falke A, Schröder N, Hofmann C (2022) The influence of values in sustainable consumption among millennials. J Bus Econ 92:899–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-021-01072-7

Farooq R (2016) Role of structural equation modeling in scale development. J Adv Manag Res. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-05-2015-0037

Featherman MS, Pavlou PA (2003) Predicting e-services adoption: a perceived risk facets perspective. Int J Hum Comput Stud 59:451–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00111-3

Fenko A, Kersten L, Bialkova S (2016) Overcoming consumer scepticism toward food labels: the role of multisensory experience. Food Qual Prefer 48:81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.08.013

Franceković P, García-Torralba L, Sakoulogeorga E, Vučković T, Perez-Cueto FJ (2021) How do consumers perceive cultured meat in Croatia, Greece, and Spain? Nutrients 13:1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041284

Francot LMA (2014) Dealing with complexity, facing uncertainty: Morality and ethics in a complex society. ARSP: Arch Rechts Sozialphilos 100:201–218

Gale BT (1994) Managing customer value: creating quality and service that customers can see. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY

Gareth J, Daniela W, Trevor H, Robert T (2013) An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R. Springer, New York, NY

Gefen D, Straub DW (2004) Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 32:407–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2004.01.006

Geiger I, Kluckert M, Kleinaltenkamp M (2017) Customer acceptance of tradable service contracts. J Bus Econ 87:155–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-016-0817-5

Gilbert DT, Malone PS (1995) The correspondence bias. Psychol Bull 117:21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21

Gimenez C, Tachizawa EM (2012) Extending sustainability to suppliers: a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag 17:531–543. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211258591

Goodman JK, Cryder CE, Cheema A (2012) Data collection in a flat world: the strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. J Behav Decis Mak 26:213–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1753

Gómez-Luciano CA, de Aguiar LK, Vriesekoop F, Urbano B (2019) Consumers’ willingness to purchase three alternatives to meat proteins in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Food Qual Prefer 78:103732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103732

Grabner-Kräuter S (2002) The role of consumers’ trust in online-shopping. J Bus Ethics 39:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016323815802

Grabner-Kräuter S, Krisch U, Breitenecker R (2018) Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility communication in Hong Kong. In: Cauberghe V, Hudders L, Eisend M (eds) Advances in advertising research IX. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden, pp 219–230

Graf C, Wirl F (2014) Corporate social responsibility: a strategic and profitable response to entry? J Bus Econ 84:917–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-014-0739-z

Grewal R, Cote JA, Baumgartner H (2004) Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models: implications for theory testing. Mark Sci 23:519–529. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1040.0070

Griskevicius V, Tybur JM, Van den Bergh B (2010) Going green to be seen: status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J Pers Soc Psychol 98:392–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017346

Gürhan-Canli Z, Batra R (2004) When corporate image affects product evaluations: the moderating role of perceived risk. J Mark Res 41:197–205. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.41.2.197.28667

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2019) Multivariate data analysis, 8th edn. Cenage Learning, Hampshire