Abstract

Corporate valuation often relies on the assumption of a constant and homogenous growth rate. However, large firms frequently (re)balance their activities by diverting cash flows from some business units to fund investments in other units. We develop a value driver model of terminal value for a firm with two units. The model relaxes common assumptions and allows for cross-unit differences in the return on invested capital. We consider intra-unit and cross-unit investments and show their implications for firm value and the long-term development of key accounting variables. Our results help characterize business unit strategies that can be reconciled with popular firm strategies such as the constant payout and constant growth strategies. We find that popular valuation methods that assume both constant payout ratios and constant growth rates (e.g., Gordon and Shapiro, Manage Sci 3:102–110, 1956) constitute a restrictive special case of our model and should only be applied to firms with homogenous business units. We use a simulation analysis to compare our results with alternative valuation models and to illustrate the economic relevance of our findings. The simulation shows that an accurate depiction of business unit strategy is particularly useful if firms plan large-scale cross-unit investments into business units with high returns and if the cost of capital is low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Value-based management aims to identify strategies that maximize shareholder value (Rappaport 1997; Ittner and Larcker 2001; Young and O’Byrne 2001). Strategic decisions typically affect firm profitability over the long term. Therefore, valuation models should account for cash flows over a long time horizon and ideally be based on a going-concern premise. The literature provides various terminal value models that determine the value of cash flows in such a going-concern scenario. Many approaches are based on the value driver model by Gordon and Shapiro (1956) and develop valuation formulas under the premise that a firm’s free cash flow grows at a constant nominal rate.Footnote 1

Yet, this assumption is inapt to describe firms with multiple business units where strategies define the product-market mix and specify the development of the portfolio of business units. In multi-business organizations, the valuation outcome should reflect information on the positioning and rentability of a firm’s strategic business units. Strategy formulation typically involves the (re)balancing of firms’ activities, which requires diverting cash flows from some business units to fund investments in other units (Solomons 1965; Kontes 2010). Such cross-unit investments generally imply that cash flows at the business unit and firm level do not increase at a constant growth rate even if business units yield constant (but heterogeneous) returns.Footnote 2 Hence, existing valuation models typically fail to depict the accurate development of the firm’s accounting measures and the corresponding value implications.

This study i) analyzes how cross-unit investments in a multi-business organization affect the long-term development of a firm’s accounting variables and ii) identifies the corresponding value effects. We extend the value driver model of Gordon and Shapiro (1956) by considering a firm with two potentially heterogeneous business units that plans cross-unit investments in all future periods. We derive and interpret valuation formulas for this setting. Moreover, we use a simulation analysis to compare our model with alternative valuation approaches. Although there might be other interdependencies between business units, we focus on the consideration of cross-unit investments. The (re)allocation of capital among business units plays an important role in the strategy formulation of multi-business organizations (Solomons 1965; Kontes 2010).Footnote 3

This study relates to existing analytical literature on corporate valuation in multi-business organizations. Similar to our approach, Koller et al. (2015) and Meitner (2013) develop terminal value models for firms with two investment opportunities, which may be interpreted as business units. These models represent special cases of our analysis and serve as benchmark cases when evaluating the economic relevance of our results. Koller et al. (2015) require that firm growth is established by a single business unit while the nominal value of the capital invested in the other unit is held constant. This is restrictive not only because other (positive or negative) growth rates could be part of a firm’s strategy, but also because in the presence of inflation a constant invested capital in real terms requires positive net investments.Footnote 4 Therefore, the model does not offer sufficient degrees of freedom to depict realistic strategies.Footnote 5 Meitner (2013) studies potential valuation errors that might occur in accounting-based valuation approaches. The analysis presumes that free cash flows at the firm level grow at a constant nominal rate, although business units exhibit heterogeneous return on invested capital (ROIC). These assumptions imply a specific investment strategy of a firm: Cross-unit investments are chosen to balance the differences in both business units. In practice, firms have access to a richer set of investment strategies, which do not necessarily imply constant growth of the aggregate free cash flow. Such strategies cannot be depicted by Meitner (2013).

We consider a generalized valuation framework of a firm with two business units that potentially differ in their invested capital and ROIC. In each business unit, a constant share of the financial surplus is invested within the same unit (intra-unit investments). Moreover, a constant share of the surplus of one business unit is diverted and invested within the other unit (cross-unit investments). In contrast to previous literature, we allow for arbitrary intra-unit and cross-unit investment rates. We develop a free cash flow calculus to determine firm value and interpret the valuation formula. The literature on value-based management emphasizes the role of residual income in implementing value-enhancing strategies (Reichelstein 1997; Young and O’Byrne 2001). Therefore, we reformulate our free cash flow valuation formula as a residual income approach. We further illustrate how investors may use firms’ segment reporting to estimate the input parameters of our valuation model. As large firms frequently pursue financial targets, such as constant payout ratios and constant growth rates of the free cash flow at the firm level, we study under which conditions constant payout and constant growth strategies can be reconciled with our model assumptions. The analysis is complemented by a simulation study to compare our valuation model with the valuation models proposed by Gordon and Shapiro (1956), Koller et al. (2015), and Meitner (2013), and to illustrate under which conditions our results especially help improve valuation precision.

Our analysis contributes to the literature on corporate valuation in various ways. First, we extend models of terminal value allowing for more general investment strategies. Existing models only consider long-term growth in some business units (Daves et al. 2004; Koller et al. 2015) or assume that all units grow at a constant rate (Meitner 2013). By contrast, we determine growth rates based on a generalized value driver model with arbitrary investment rates. We further consider that firms hold invested capital in all of their business units. Previous literature assumes that firms have invested capital in only one unit before they start to fund additional investments in the steady-state period (Meitner 2013; Koller et al. 2015). Thus, we propose a unified valuation framework for firms with multiple business units that offers additional degrees of freedom.

Second, our analysis may assist in understanding the effects of a firm’s business unit strategy on the expected development of its financials. We show how intra- and cross-unit investment rates, as well as business unit rentability, affect forecasts of accounting measures such as invested capital, free cash flow, and residual income. Moreover, we study the long-term growth of these accounting measures, the long-term ROIC, and the long-term payout ratio. This is important as many firms pursue target payout or growth rates, for instance as a signal to investors (Stone 1972; Brav et al. 2005; Graham et al. 2005). We identify premises that ensure constant payout ratios or constant nominal growth of the free cash flow. Our results could help in formulating business unit strategies that are compatible with financial targets at the firm level. For instance, we show under which conditions the free cash flow grows at a constant rate although there may be considerable differences in the characteristics and the long-term development of single business units.

Third, our analysis may be useful not only for management with regard to the evaluation of strategic alternatives, but also for financial analysts and investors who can use our results for fundamental analysis and investment decisions. They typically do not have access to strategic information. Yet, our findings offer guidance on how to estimate value drivers based on disclosures about firms’ business units, which are typically part of mandatory financial reports. For instance, IFRS 8 requires public firms to disclose management information on the size and profitability of their business segments. We illustrate how such information may be used to learn about a firm’s investment strategy, to identify shifts in its business activities, and to assess implications for firm value. Furthermore, we use a simulation analysis to illustrate the benefits of our model. We compare valuation outcomes with the benchmark models of Koller et al. (2015) and Meitner (2013) and with the popular value driver model. We show that our model improves valuation precision by 3.4%–6.4%. As the practical application of more elaborate valuation models may be accompanied by considerable costs, we use sensitivity analysis to show under which conditions a more accurate valuation is particularly desirable. We find considerable valuation errors if firms plan large-scale cross-unit investments into business units with high returns and if the cost of capital is low. These factors crucially affect the value of the cross-unit investments, which is incorrectly depicted in the benchmark models.

Fourth, our results are related to empirical work on value creation in diversified firms. Empirical studies document a diversification discount, signifying that values of multi-business firms tend to be lower than the stand-alone values of their segments (Berger and Ofek 1995). While there may be benefits of diversification, such as a reduced tax burden or a higher debt capacity, the literature finds that they are typically outweighed by detrimental effects such as aggravated agency conflicts (Hoechle et al. 2012) and subsidizations of underperforming business units (Rajan et al. 2000). Our model explicitly considers cross-unit investments between business units that differ in their profitability. Our findings may help in identifying cross-unit investments and quantifying value gains (and potential losses) of cross-subsidization. Therefore, our results could be useful in establishing transparency with regard to the financial consequences of firm diversification.

2 A valuation model with two business units and heterogeneous ROIC

2.1 Model setup

We consider a firm with two business units, referred to as units A and B.Footnote 6 As typical in the theoretical literature, the valuation is based on a given investment and financing strategy.Footnote 7 The strategy formulation relates to the business unit level. To depict the long-term consequences of managers’ strategy choices, we assume a going concern. Both business units generate financial surpluses in all future points in time (\(t=1,2,...\)). We assume that the firm’s lifetime is divided into two forecast periods (Arzac 2008; Titman and Martin 2011). In the explicit forecast period, financial surpluses are predicted using detailed forecasting models that consider contractual relationships and the expected market development. In the steady-state period, both units have arrived in a steady state such that cash flow forecasts follow a simple pattern. In the following analysis, we focus on the determination of the terminal value, that is, the value of the cash flows in the steady-state period (Titman and Martin 2011).Footnote 8 For notational convenience, we define \(t=0\) as the beginning of the steady-state period. Moreover, let \(E[\widetilde{IC}_t^A]\) and \(E[\widetilde{IC}_t^B]\) denote the expected invested capital in business units A and B at time t.Footnote 9 The invested capital at time \(t=0\) results from the planning process in the explicit forecast period.

We assume that the firm strategy implies forecasts of business unit profitability. The units possibly differ in their specific ROIC, that is, the ratio of the expected net operating profit less adjusted taxes (NOPLAT) and the invested capital at the beginning of the respective period. We assume constant ROIC for both units in the steady-state period:

where  denotes the NOPLAT of unit \(i \in \left\{ A,B \right\}\) at time \(t\ge 1\). Profitability may differ across business units. For instance, unit A represents the firm’s previous field of business and unit B an investment opportunity that is important in the future. In this case, it is likely that unit A is characterized by a higher ROIC because it can build on existing relationships to its suppliers and customers (Daves et al. 2004; Koller et al. 2015). We do not impose any assumptions on the relative magnitude of \(ROIC^A\) and \(ROIC^B\) to allow for more general firm strategies.Footnote 10

denotes the NOPLAT of unit \(i \in \left\{ A,B \right\}\) at time \(t\ge 1\). Profitability may differ across business units. For instance, unit A represents the firm’s previous field of business and unit B an investment opportunity that is important in the future. In this case, it is likely that unit A is characterized by a higher ROIC because it can build on existing relationships to its suppliers and customers (Daves et al. 2004; Koller et al. 2015). We do not impose any assumptions on the relative magnitude of \(ROIC^A\) and \(ROIC^B\) to allow for more general firm strategies.Footnote 10

In line with existing terminal value models, we assume that firm strategy translates into constant net investment rates (Koller et al. 2015).Footnote 11 The strategy specifies intra-unit net investments, as well as cross-unit investments at the business unit level. The intra-unit investment rates \(n^A\), \(n^B \in [0,1]\) define net investments as the share of the NOPLAT of units A and B that is reinvested within the same business unit. In addition, a constant share \(n^{AB}\) of business unit A’s NOPLAT after intra-unit investments is used to fund additional investments in unit B.Footnote 12 We refer to \(n^{AB}\) as the cross-unit investment rate. Given the NOPLATs at time \(t\ge 1\), the business units’ expected net investments are given by:

\(\overline{n}^{AB} = n^{AB} \cdot (1-n^A)\) represents the effective cross-unit investment rate related to the NOPLAT of unit A. The net investment rates shape the development of the invested capital over time:

The firm’s expected free cash flow equals its NOPLAT after net investments:Footnote 13

Finally, we assume active debt management with a constant leverage ratio and make the simplifying assumption that the same weighted average cost of capital k applies to the cash flows of both business units.Footnote 14 Moreover, we assume that investments in both units are not value-destroying; that is, \(k \le \min \{ROIC^A,ROIC^B\}\). Otherwise, investments should be omitted.

In practice, the business units of a firm may be subject to different types of interdependencies. We focus on cross-unit investments, where cash flows earned in one unit are used to fund investments in other units. Such practices play a major role in the process of strategy formulation. Budgets are reallocated over the long term to optimize the product portfolio (e.g., to shift capital toward more profitable products) and account for changes in the firm’s environment (Solomons 1965; Kontes 2010). Defining constant cross-unit investment rates captures the idea of long-term capital reallocations and naturally extends existing terminal value models, which typically assume constant net investment rates at the firm or business unit level.

In addition to cross-unit investments, there might be other types of interdependencies: For instance, business units potentially face cost-sided or demand-sided interdependencies (e.g., the joint use of non-financial resources or complementarities in demand in related product markets). Such interdependencies should be considered in the forecast of rentability. Furthermore, firms’ investment in multiple business units may be a measure to diversify their operational and financial risk. If the business units are exposed to common risk factors, adjustments to the business portfolio would affect firm risk and debt capacity (Lewellen 1971). Thus, cross-unit investments may have an additional effect on the firm value by increasing debt tax shields and changing the firm’s cost of capital. We assume a constant cost of capital and neglect such financing considerations, leaving potential extensions for future research. We also neglect potential tax benefits of diversification that may be related to shifts in financial outcomes of a firm’s business units (Majd and Myers 1987). Instead, we focus on changes in the firm’s operational performance and their implications for firm value.

2.2 Benchmark analysis

To illustrate the features of our model, we compare it with existing valuation approaches. First, assume that the business units are independent (\(n^{AB} = 0\)). Thus, the terminal value can be determined by applying the value driver model of Gordon and Shapiro (1956) at the business unit or firm level.Footnote 15

Benchmark

(Gordon and Shapiro 1956 ) Independent business units, \(n^{AB}=0\)

-

(a)

A firm’s terminal value is the sum of the business unit values \(E[\tilde{V}_0^A]\) and \(E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\) according to the value driver model with the nominal growth rates \(g^i = n^i \cdot ROIC^i\):

-

(b)

With homogenous units (\(ROIC = ROIC^A = ROIC^B\), \(n = n^A = n^B\) ), the value driver model can be applied at the firm level, with the uniform growth rate \(g = n \cdot ROIC\):

Without cross-unit investments, the stand-alone values of the business units can be determined using the value driver model. The expected free cash flow of unit \(i \in \{ A,B\}\) at \(t=1\) is obtained by applying the payout ratio \(1 - n^i\) to the NOPLAT,  . It is easy to see that this free cash flow grows at the constant nominal rate of \(g^i = n^i \cdot ROIC^i\). Thus, the stand-alone value of unit i is the value of a perpetuity with constant growth \(g^i\) and cost of capital k (Gordon and Shapiro 1956).Footnote 16 A firm’s terminal value is the sum of the stand-alone values, as illustrated in benchmark case (a). If we further assume that the firm plans identical net investment rates in both units and that there are no differences in the ROIC, the value driver model can even be applied to firm-level data as shown in benchmark case (b).

. It is easy to see that this free cash flow grows at the constant nominal rate of \(g^i = n^i \cdot ROIC^i\). Thus, the stand-alone value of unit i is the value of a perpetuity with constant growth \(g^i\) and cost of capital k (Gordon and Shapiro 1956).Footnote 16 A firm’s terminal value is the sum of the stand-alone values, as illustrated in benchmark case (a). If we further assume that the firm plans identical net investment rates in both units and that there are no differences in the ROIC, the value driver model can even be applied to firm-level data as shown in benchmark case (b).

Arguably, the usefulness of these formulas in valuing a portfolio of business units is limited. Firms distinguish business units due to differences in the underlying economic conditions. Therefore, it is unlikely that these units are equally profitable. Moreover, it seems artificial to assume that firms formulate business unit strategies without considering cross-unit investments. Technological development and changes in firms’ competitive environment require firms to balance their business portfolio and to shift resources from some business units to others.

Meitner (2013) and Koller et al. (2015) consider cross-unit investments under restrictive assumptions. The valuation formulas are presented as benchmark models (c) and (d).

Benchmark

Alternative models of terminal value with two business units

-

(c)

Koller et al. (2015): If a firm does not invest in unit B before \(t = 1\), the nominal capital of unit A is held constant, and the cross-unit investment rate equals the net investment rate of unit B, \(E[\widetilde{IC}_0^B] = n^A = 0\), \(n^{AB} = n^B\), the terminal value is given by

-

(d)

Meitner (2013): With no initial capital in business unit B, that is, \(E[\widetilde{IC}_0^B] = 0,\) and a cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB} = (g^B - g^A)/(ROIC^B - g^A)\), the terminal value is

Koller et al. (2015) assume that the nominal value of unit A’s invested capital is held constant. Moreover, the cross-unit investment rate is assumed to be identical to the intra-unit investment rate of unit B. As this unit is initially not endowed with invested capital, the firm value is the sum of two components: The first component reflects the stand-alone value of unit A in the absence of cross-unit investments. This unit generates a perpetuity of  , which is discounted at the firm’s cost of capital k. The second component represents the net value contribution of the cross-unit investments. This component depends on the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB} = n^B\) and on the growth rate \(g^B\) of unit B. Intuitively, any growth in business unit A should affect both the stand-alone value of unit A and the net contribution of the cross-unit investments. We confirm this intuition in our generalized model.

, which is discounted at the firm’s cost of capital k. The second component represents the net value contribution of the cross-unit investments. This component depends on the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB} = n^B\) and on the growth rate \(g^B\) of unit B. Intuitively, any growth in business unit A should affect both the stand-alone value of unit A and the net contribution of the cross-unit investments. We confirm this intuition in our generalized model.

For given returns and intra-unit investment rates, Meitner (2013) assumes cross-unit investments that ensure a constant growth rate of the firm’s free cash flow. Given the assumptions of benchmark case (d), the firm’s aggregate free cash flow at \(t=1\) is

and grows at the constant rate \(g^B\).Footnote 17 The terminal value corresponds to the value of a perpetuity with growth rate \(g^B\) and cost of capital k. The simple valuation formula in case (d) comes at a cost: The model implicitly imposes restrictive assumptions regarding the balancing of the units’ budgets and rules out a variety of business unit strategies. Our valuation approach offers additional degrees of freedom and is therefore useful in depicting firms’ terminal value with higher precision.Footnote 18

3 Model analysis

3.1 Long-term development of accounting measures and firm value

First, we use the definitions in the previous section to develop inductively closed-form solutions for the business units’ accounting measures. Lemma 1 illustrates how the value drivers of both units jointly affect the accounting measures if we consider cross-unit investments.Footnote 19

Lemma 1

Development of the business units’ accounting measures

-

(a)

The invested capital, NOPLAT, and net investments of business unit A are given by

-

(b)

The invested capital, NOPLAT, and net investments of business unit B are

All investments in business unit A are funded from its NOPLAT according to the net investment rate \(n^A\) and yield a return of \(ROIC^A\). Consequently, the invested capital, NOPLAT, and net investments of this unit grow at the nominal rate \(g^A\). By contrast, the expected accounting measures of unit B depend on both growth rates \(g^A\) and \(g^B\), which is an intuitive result. Periodically, a constant share \(\overline{n}^{AB}\) of the NOPLAT in business unit A is invested into unit B. The rate \(g^A\) determines the growth of this NOPLAT and therefore, the magnitude of the cross-unit investments. Once the firm has diverted the budget from business unit A into unit B, all subsequent investments yield \(ROIC^B\) and are characterized by the growth rate \(g^B\). Lemma 1 (b) shows that the invested capital, NOPLAT, and net investments in unit B do not grow at a constant rate.

To understand the long-term development of a firm, we analyze the growth rates of invested capital, net investments, NOPLAT, and free cash flow at the firm level:

We further study the firm’s aggregate return \(ROIC_t\) and total payout ratio \(q_t\) at time t:

Proposition 1 shows the effects of the planning premises on the long-term development of these measures. Based on Lemma 1 , we determine the growth rates, ROIC, and payout ratio according to equations (7, 8) and study their limit values.

Proposition 1

The long-term development of the growth rates, ROIC, and payout ratio

-

(a)

The growth rates of the firm’s invested capital, net investments, NOPLAT, and free cash flow gradually converge toward the maximum of the business units’ growth rates:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow \infty } g_t^x = \max \{g^A,g^B\} \ \ \ {for}\ x \in \left\{ IC,NI,NOPLAT,FCF \right\} . \end{aligned}$$ -

(b)

The limits of the firm’s ROIC and payout ratio are given by,

$$\begin{aligned} &\displaystyle ROIC^\infty = \mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow \infty } ROIC_t = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} ROIC^B & \mathrm{\it{if}}\ g^B \ge g^A\\ \lambda ^{ROIC} \cdot ROIC^A + (1 - \lambda ^{ROIC}) \cdot ROIC^B & \mathrm{\it{if}}\ g^B< g^A \end{array} \right. ,\\ & q^\infty = \mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow \infty } q_t = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 - n^B & \mathrm{\it{if}} \ g^B \ge g^A\\ \lambda ^q \cdot (1 - n^A) \cdot (1 - n^{AB}) + (1 - \lambda ^q) \cdot (1 - n^B)&{} \mathrm{\it{if}} \ g^B < g^A \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$with weights \(\displaystyle \lambda ^{ROIC} = \frac{g^A - g^B}{g^A - g^B + \overline{n}^{AB} \cdot ROIC^A}\) and \(\displaystyle \lambda ^q = \frac{g^A - g^B}{g^A - g^B + \overline{n}^{AB} \cdot ROIC^B}.\)

The growth rates of the accounting measures converge to the maximum of \(g^A\) and \(g^B\). Thus, we find that long-term forecasts of growth rates should not be interpreted as the average growth of a firm’s business units, but reflect the business that yields the maximum growth. This unit has a dominant effect on firm financials in the long-run. Interestingly, this result is independent of the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB}\). Even if the investments in unit B are primarily funded by cross-unit investments, the long-term growth of the firm’s aggregate free cash flow solely depends on the growth established within both units.

The development of the firm’s ROIC depends on the relative magnitude of both growth rates. For \(g^B \ge g^A\), the total ROIC converges to the return in business unit B. By contrast, the limit of the total ROIC is a weighted average of the returns \(ROIC^A\) and \(ROIC^B\) of both units for \(g^B < g^A\). This result reflects the fact that the growth rate \(g^B\) exclusively influences financial surpluses of unit B, while the growth rate \(g^A\) has an impact on both units. For high values of \(g^A\), both units continue to be important for the firm, and the long-term ROIC depends on the specific investment rates. A similar result is obtained with regard to the firm’s total payout ratio \(q_t\). It approaches the payout ratio \(1-n^B\) of unit B if this unit’s growth rate exceeds the growth in unit A. For \(g^B < g^A\), the long-term payout ratio is a weighted average of the effective payout ratios \((1-n^{AB}) \cdot (1-n^A)\) and \(1-n^B\) of both units.Footnote 20

In Corollary 1, we focus on the case wherein business unit A is characterized by a higher growth rate than unit B. We study how the value drivers affect the weights \(\lambda ^{ROIC}\) and \(\lambda ^{q}\) of unit A’s ROIC and the payout ratio in the determination of \(ROIC^\infty\) and \(q^\infty\).

Corollary 1

Assume \(g^B < g^A\). The weights \(\lambda ^{ROIC}\) and \(\lambda ^{q}\) related to unit A’s return and payout ratio increase in the net investment rate and return of this unit and decrease in the net investment rate and return of unit B and in the cross-unit investment rate.

Business unit A is more important for the long-term development of the firm if this unit yields a higher return and if a larger part of its NOPLAT is reinvested within unit A. By contrast, the firm’s long-term ROIC and payout ratio are rather aligned with unit B if this business unit is characterized by a high ROIC and high net investment rate. If the firm chooses a higher cross-unit investment rate, this implies additional investments into unit B. Thus, the total ROIC and the payout ratio approach \(ROIC^B\) and \(1-n^B\).

Our model provides a deeper understanding of the development of accounting measures in a steady-state period. Although our assumptions do not adhere to the common idea of constant and uniform growth of all relevant metrics, we provide a closed-form valuation formula that offers a tractable way to determine terminal value in a free cash flow calculus. The process of firm valuation can be divided into three steps. First, we determine the stand-alone values \(E[\tilde{V}_0^A]\) and \(E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\) of both units according to benchmark model (a). Second, we identify the net contribution \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\) of cross-unit investments to firm value. Cross-unit investments reduce the free cash flow in early periods, but increase the cash flow in later periods. \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\) represents the present value of these changes. The firm’s terminal value is determined in a third step by adding up the three components. Proposition 2 shows the free cash flow calculus.

Proposition 2

The terminal value \(E[\tilde{V}_0]\) is the sum of the stand-alone values of both units, \(E[\tilde{V}_0^A]\) and \(E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\), and the net contribution of the cross-unit investments \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\):

If we neglect cross-unit investments, the business units would become independent of each other. The value \(E[\tilde{V}_0^i]\) of unit \(i \in \{ A,B\}\) can be determined according to the value driver model with growth rate \(g^i\) and cost of capital k. Cross-unit investments change free cash flows to the shareholders and debtors in two ways. First, in each period, only a share \(1 - n^{AB}\) of business unit A’s surplus is distributed, which reduces the firm’s free cash flow. Second, the retained amount is used to fund investments in unit B and results in incremental free cash flow in all future periods. The net value contribution \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\) aggregates the value-reducing effect from higher retention of the surpluses in unit A and the value-enhancing effect due to the increasing future free cash flow generated in unit B.

Note that the net value contribution of cross-unit investments \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\) depends on the growth rates of both business units. If the growth rate \(g^A\) of unit A increases, this implies higher periodic NOPLAT in this unit and higher subsidies to unit B. Each investment in unit B is followed by an infinite sequence of reinvestments according to the net investment rate \(n^B\) and thus, yields financial surpluses that grow at the nominal rate \(g^B\).

Corollary 2

The value of cross-unit investments \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\) is increasing in both business units’ ROICs and net investment rates, but decreasing in the firm’s cost of capital:

We assume that the rentability of business unit B exceeds the cost of capital. Thus, cross-unit investments into unit B always generate a positive value \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\): It is beneficial to retain and invest cash flows into unit B rather than distribute them. Therefore, it is not surprising that a higher rentability \(ROIC^B\) and net investment rate \(n^B\) increase \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\). Moreover, a higher cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB}\) and a higher return \(ROIC^A\) in unit A increase the magnitude of the value-enhancing cross-unit investments and the component \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\). The effect of the net investment rate in unit A is less obvious. Increasing \(n^A\) reduces the share \(\overline{n}^{AB}\) of the NOPLAT of unit A that is invested into unit B. At the same time, the additional net investments in unit A raise future surpluses of this unit and allow for higher cross-unit investments in all subsequent periods. Corollary 2 shows that the latter effect is dominant. Not surprisingly, a higher cost of capital reduces the benefits of cross-unit investments.

The benchmark models mainly differ in the value contribution of the cross-unit investments \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\). The application of the value driver model at the business unit level according to the benchmark model (a) neglects this component completely. Benchmark model (b) presumes a constant net investment rate at the firm level and does not reflect the dynamic development of the investments in both business units. Models (c) and (d) impose assumptions on the level of the cross-unit investment rate, either equalizing \(n^{AB}\) with the net investment rate of unit B (Koller et al. 2015) or assuming that the firm’s free cash flow grows at a constant rate (Meitner 2013). Moreover, model (c) does not consider the nominal growth within unit A and the complementary effect of both units’ growth rates on \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{AB}]\). Ignoring the growth within unit A may lead to severe forecasting errors. Proposition 1 shows that the accurate depiction of the relative magnitude of \(g^A\) and \(g^B\) crucially affects the forecasts of accounting measures.

3.2 Business unit strategy and residual income measures

An obvious application of our results concerns value-based management. Firms may translate alternative business unit strategies into value drivers and assess their implications for the development of accounting measures and firm value. The literature on value-based management emphasizes the role of adequate performance metrics in strategy implementation and particularly highlights potential benefits of residual income: This measure is closely related to value creation and can help prevent myopic behavior of a firm’s management (Reichelstein 1997; Young and O’Byrne 2001). Furthermore, empirical work shows that valuation methods based on residual income are frequently used in corporate practice (Plenborg 2002; Damodaran 2005; Imam et al. 2008). Therefore, we highlight the link between business unit strategy and residual income valuation.

Residual income accounts for the fact that revenues should cover operating expenses as well as the firm’s capital cost. Thus, the residual income of unit \(i \in \{ A,B\}\) at time t is

According to the conservation property of residual income, the terminal value of a firm equals the sum of the initially invested capital and the market value added (MVA):

The MVA \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0]\) can be interpreted as the value contribution of investments in the steady-state period. In Corollary 3, we illustrate the development of the business units’ residual income and state a valuation formula based on a residual income approach.

Corollary 3

Development of residual income and firm value

-

(a)

The residual incomes of business units A and B at time t are given by

-

(b)

The terminal value is the sum of the initially invested capital, the stand-alone MVAs of the units \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^i]\), \(i \in \{ A,B\}\), and the MVA of the cross-unit investments \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^{AB}]\):

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle E[\tilde{V}_0] = E[\widetilde{IC}_0] + E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^A] + E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^B] + E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^{AB}] \end{aligned}$$with \(\displaystyle E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^i] = \frac{ROIC^i - k}{k - g^i} \cdot E[\widetilde{IC}_0^i] , E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^{AB}] = \frac{\overline{n}^{AB} \cdot ROIC^A \cdot (ROIC^B - k)}{(k - g^A) \cdot (k - g^B)} \cdot E[\widetilde{IC}_0^A].\)

Unit A does not receive any cross-unit investments, and the unit’s residual income grows at the rate \(g^A\). However, the residual income of unit B is affected by the growth established by both units and does not increase at a constant rate. The residual income of unit \(i \in \{ A,B\}\) is proportional to the excess return \(ROIC^i - k\) that is attainable in this unit.

The formula in Corollary 3 (b) has a similar structure as the discounted cash flow calculus in Proposition 2. If we neglect cross-unit investments, both NOPLAT and invested capital of unit \(i \in \{ A,B\}\) grow at the rate \(g^i\). Thus, the residual income grows at the same rate, and we obtain \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^i]\). The cross-unit investments at time t are given by \(\overline{n}^{AB} \cdot ROIC^A \cdot E[\widetilde{IC}_{t - 1}^A]\), which implies an incremental residual income of \(\overline{n}^{AB} \cdot ROIC^A \cdot E[\widetilde{IC}_0^A] \cdot (ROIC^B - k)\) at time \(t+1\). This residual income grows at the rate \(g^B\). If we consider the growth \(g^A\) of unit A’s NOPLAT, we obtain \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^{AB}]\) according to Corollary 3. The terminal value is the sum of the initially invested capital and the MVAs.

3.3 Learning value drivers from business unit data

The results of the previous sections may be useful for a firm’s management to assess business unit strategies with cross-unit investments. External parties, such as investors or financial analysts, typically do not have access to firms’ strategic plans and cannot directly apply our findings. Yet, our results offer guidance with regard to estimating a firm’s value drivers if external parties have basic financial information on the firm’s business units.

For instance, the IASB requires public companies to disclose such information in their segment reporting. According to IFRS 8, affected firms are supposed to report information on total assets, profit, interest expense, depreciation, and income tax expense for sufficiently large operating segments. Identification of the relevant segments and the presented accounting numbers must be consistent with internal management information. Firms are allowed to aggregate segments only if they share similar economic characteristics. Arguably, external parties do not make significant mistakes if they interpret these segments as the firm’s strategic business units and use segment data to infer information about business unit strategy.Footnote 21

To illustrate a simple estimation that is consistent with our model framework, assume that there is financial information on a firm with two business units, \(i \in \{ A,B\}\), for three years, \(t \in \{ 0,1,2\}\). If we assume that the three years represent the beginning of the steady-state period and that the realized accounting variables are close to their expected values (i.e., \(x_t^i = E[\tilde{x}_t^i]\) for \(x \in \{NOPLAT,IC\}\)), it is sufficient to know the units’ invested capital and NOPLAT. Based on this information, the net investments are given by \(NI_t^i = IC_t^i - IC_{t - 1}^i\). The units’ returns can be estimated using the formulas in Lemma 1:

Given these returns, we can use the data to infer the net investment rate of unit A,

the net investment rate \(n^B\), and the cross-unit investment rate \(\overline{n}^{AB}\) related to the NOPLAT as follows:

These estimates may be used to forecast the business units’ accounting measures (Lemma 1 and Proposition 1) or to determine the firm’s terminal value (Proposition 2). Note that this approach may lead to considerable estimation errors if the accounting variables are very volatile and realized values deviate from the expected values. In this case, it may be inevitable to consider data for more than three periods.

3.4 Analysis of special cases

Empirical research on financial strategy choices shows that firms frequently pursue strategies that reduce the volatility of accounting variables over time. For instance, the survey by Graham et al. (2005) indicates that firms pursue a smooth development of accounting earnings because “smooth earnings make it easier for analysts and investors to predict future earnings”, and such dynamics are associated with less risk.Footnote 22 In line with this observation, Stone (1972) argues that firms engage in cash management to smooth cash flows. Brav et al. (2005) find evidence regarding firms’ endeavors to smooth dividends and highlight the prevalence of target payout ratios. We conclude that strategy formulation typically relies on the target levels of value drivers, such as growth rates and payout ratios.

Due to their high practical relevance, we analyze the conditions for a constant payout or constant growth strategy within our model setting. Specifically, we assume that firms try to maintain either a time-invariant payout ratio or constant growth of free cash flow (\(q_t = q\) or \(g_t^{FCF} = g^{FCF}\) for \(t \ge 1\)), for instance, as a signal to potential investors. Both objectives are consistent with the assumptions of the value driver model according to benchmark case (b). A constant net investment rate n at the firm level implies a constant payout ratio \(q=1-n\) and (for a given ROIC) a constant growth rate \(g^{FCF} = n \cdot ROIC\). The previous analysis documents that strategy formulation at the business unit level does not necessarily yield such results, even if intra- and cross-unit investment rates are constant.

Proposition 3 shows under which conditions our model can be aligned with the objectives of a constant payout ratio or constant growth of the aggregate free cash flow.Footnote 23

Proposition 3

Special cases of the terminal value model

-

(a)

A constant payout strategy requires that \(n^A \le n^B\) and that the (effective) payout ratios related to the NOPLAT of business units A and B are identical:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle q = (1 - n^{AB}) \cdot (1 - n^A) = 1 - n^B \ \ \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \ n^{AB} = \frac{n^B - n^A}{1 - n^A}. \end{aligned}$$ -

(b)

For \(g^B \ge g^A\), achieving constant growth of a firm’s free cash flow requires that

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle (1 - n^{AB}) \cdot \left( 1 - \frac{g^A}{ROIC^B} \right) = 1 - n^B \ \ \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \ n^{AB} = \frac{g^B - g^A}{ROIC^B - g^A}. \end{aligned}$$

The proposition shows that constant payout and constant growth strategies represent special cases of our model. The conditions in parts (a) and (b) ensure that the payout ratio according to (8) and the growth rate of the free cash flow according to (7) are time invariant. Both conditions have a very intuitive interpretation. A constant payout strategy can be achieved if both units effectively apply the same payout ratio.Footnote 24 In this case, the limit of the total ROIC according to Proposition 1 (b) can be simplified as follows

Furthermore, the valuation formula can be restated in the following way:

The special case in Proposition 3 (b) is useful for understanding valuation models that assume constant growth of the free cash flow. These models do not necessarily assume economic homogeneity of a firm’s business units; instead, constant growth of the free cash flow may be the result of a complex disaggregate budgeting process with multiple business units that potentially grow at different rates. Our analysis highlights the assumptions that nevertheless yield constant growth of the firm’s free cash flow.Footnote 25 The firm’s free cash flow grows at the rate

It is important to note that a constant growth strategy neither implies constant growth rates of total NOPLAT, net investments, and invested capital nor is accompanied by a constant ROIC at the firm level. Thus, the development of the firm’s accounting measures cannot be depicted by the value driver model. The valuation formula can be simplified to

The simplicity of (17) comes at the cost of the cross-unit investment rate having to meet the condition in Proposition 3 (b). If a firm’s strategy violates this condition, the formula may cause significant errors. For a constant growth strategy, the firm’s long-term ROIC and payout ratio approximate the ROIC and payout ratio of unit B:

Corollary 4 studies the applicability of the value driver model in our setting with two business units.

Corollary 4

The special cases of constant payout and constant growth strategy coincide if both business units exhibit identical ROIC, that is, for \(ROIC = ROIC^A = ROIC^B\). In this case, the terminal value can be determined using the value driver model:

Corollary 4 highlights the role of intra-firm heterogeneity in our valuation approach. The application of the value driver model according to benchmark case (b) requires constant payout ratios and constant growth of the firm’s free cash flows. To obtain this result, the two special cases must coincide. However, this cannot occur unless the units generate identical ROIC. For all other cases, firm value must be determined with the valuation formula presented in Section 3.1.

4 Simulation analysis

4.1 Premises

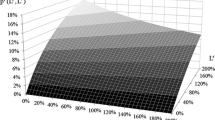

To illustrate the economic relevance of our model, we use a simulation analysis and compare our results with those of the benchmark models introduced in Section 2.2. We consider a population of 100,000 firms with a given business unit strategy according to our model setup.

The benchmark models cannot correctly depict the firms’ strategy formulation. Their results are subject to valuation errors. In the following, we briefly describe the application of the benchmark models to the data. Benchmark model (a) applies the value driver model to each unit. The model does not offer any degree of freedom to consider the cross-unit investment rate. Therefore, we neglect the cross-unit investments and determine the firm value \(E[\tilde{V}_0^a]\) as the sum of the stand-alone values \(E[\tilde{V}_0^A]\) and \(E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\).

Benchmark model (b) relies on the assumptions of a constant ROIC and net investment rate at the firm level. Given our model of business unit strategies, these assumptions are not satisfied. Thus, the application of model (b) requires a heuristic to determine the value drivers. We estimate the parameters given the first period’s accounting information:

It is evident from the previous analysis that these numbers do not correspond to the firm’s actual ROIC and net investment rate in any period \(t \ge 2\). We use the value drivers in (19) to determine the terminal value \(E[\tilde{V}_0^b]\).

Benchmark model (c) does not consider the nominal growth in business unit A. Therefore, we neglect any positive intra-unit investment rate \(n^A\). Furthermore, the cross-unit investment rate must be fixed at the level of the intra-unit investment rate of unit B, \(n^{AB} = n^B\). Moreover, the benchmark model does not consider the initial capital in unit B. While the latter assumption clearly limits the model’s applicability, it is not related to the depiction of cross-unit investments and can easily be relaxed. To ensure comparability of the simulation results, we extend the model for the invested capital in unit B. The terminal value is given by \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{c'}] = E[\tilde{V}_0^c] + E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\), where the stand-alone value \(E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\) reflects the contribution of the initial capital in unit B.

According to benchmark model (d), the information on the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB}\) is neglected. Instead, cross-unit investments are chosen to ensure a constant growth strategy. Following the above-mentioned argument, we also extend the model for initial capital in unit B, \(E[\tilde{V}_0^{c'}] = E[\tilde{V}_0^c] + E[\tilde{V}_0^B]\). This guarantees comparability of the simulation results and a fair assessment of the benchmark model.

4.2 Simulation results

First, we illustrate the results on our generalized valuation model. Table 1 provides an analysis of the terminal value, the long-term ROIC, and long-term payout ratio.

The population of firms has an average terminal value of 36,805.19 with a standard deviation of 7,981.73.Footnote 26 The sensitivity analysis reveals the most influential value drivers. Not surprisingly, the cost of capital k has a large (negative) impact on terminal value. The sensitivity of the terminal value to the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB}\) is \(2.7\%\) and exceeds the sensitivity to the intra-unit investment rates, which is negligible in our numerical example. The consideration of cross-unit investments affects the relative importance of the units’ value drivers. Part of the cash flow earned in unit A is not distributed, but is invested into unit B and has an additional effect on value creation. Thus, the initial capital, ROIC, and intra-unit investment rate of unit A have larger impact on terminal value than the respective value drivers of unit B.

We further study which factors affect a firm’s long-term ROIC and long-term payout ratio as defined in Proposition 1. Clearly, both units’ ROICs affect the long-term ROIC. As suggested by the theoretical analysis, the ROIC of unit B is particularly important with a sensitivity of \(98.7\%\). This unit receives subsidies from unit A, supporting its long-term growth and stressing its relevance for the long-term development of the firm. The variation of the long-term payout ratio is mainly explained by the intra-unit investment rates (\(-45.8\%\) and \(-48.4\%\) for units A and B, respectively). The long-term payout ratio is the weighted average of the effective payout ratios \((1 - n^A) \cdot (1 - n^{AB})\) and \(1 - n^B\) of the business units. Interestingly, the impact of the cross-unit investment rate is negligible. Increasing levels of \(n^{AB}\) reduce the effective payout ratio of unit A but simultaneously reduce the weight \(\lambda ^q\) assigned to this value; that is, the payout ratio of unit B becomes more important for the long-term development of the firm. Furthermore, the ROICs of both units affect \(q^\infty\). They change the relative size of the units and thereby, the weight \(\lambda ^q\).

Second, we compare our model results with the benchmark models. For each model \(x \in \{ a,b,c',d'\}\) and each observation, we study the sign of the valuation error, as well as the absolute and relative valuation errors

Table 2 documents the frequency of undervaluations, as well as the arithmetic mean, maximum, and standard deviation of the valuation errors. Moreover, we provide a sensitivity analysis of the relative valuation errors. Recall that model (d) requires that the growth rate of unit B exceeds the growth rate of unit A (\(g_B \ge g_A\) ) to avoid the economically questionable case of negative cross-unit investments. Therefore, we impose different numerical assumptions to allow for an unbiased comparison.Footnote 27

The simulation results show that all benchmark models cause considerable mean valuation errors in the range of 1,401.89–2,540.41, which represents a mean deviation of 3.4–\(6.4\%\) of the terminal values. The valuation outcome of model (a) is generally too low, all other models cause under- or overvaluations. The models show noteworthy differences in the maximum valuation error. While models (a), (c), and (d) are accompanied by maximum errors of \(22.0\%\) to \(25.8\%\), model (b) causes severe errors of up to \(56.9\%\).

The sensitivity analysis identifies two parameters that have similar effects on the relative valuation error in all benchmark models. First, the cross-unit investment rate has a substantial impact. This is not surprising as all models consider the cross-unit investments incorrectly. Model (a) completely neglects such investments. In model (b), investments are incorrectly considered by a constant net investment rate at the firm level. Models (c) and (d) either equalize the cross-unit investment rate with the intra-unit investment rate of unit B or use cross-unit investments to ensure a constant growth strategy. Second, the firm’s cost of capital reduces the relative error \(p^x = a^x /E[\tilde{V}_{0}]\) in all models. While the cost of capital reduces both the absolute error \(a^x\) and the value \(E[\tilde{V}_{0}]\), its effect on the numerator is stronger. The absolute error mainly relates to the value contribution of the cross-unit investments, which is particularly sensitive to the cost of capital.

The remaining sensitivities can be explained by the specific model features. Model (a) completely neglects the cross-unit investments. We assume that such investments yield a return that exceeds the firm’s cost of capital. Thus, the benchmark model generally implies undervaluation. On average, the valuation error is \(6.3\%\), with a maximum error of \(25.2\%\) and a standard deviation of \(4.4\%\). The valuation error is sensitive to the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB}\) (\(73.0\%\)) and to the ROIC of unit B (\(10.7\%\)), which crucially determines the contribution of the cross-unit investments.

Benchmark model (b) is based on the assumption of a constant ROIC and net investment rate at the firm level, which we estimate from the numbers in the first period. Proposition 1 shows that the actual ROIC and net investment rate might increase or decrease over time, depending on the relative size of the units’ ROICs. Thus, model (b) leads to under- and overvaluations. We identify undervaluation in \(29.0\%\) of all observations. The mean valuation error of \(3.4\%\) is comparably low. Yet, the standard deviation is higher than in the other models, and the maximum error amounts to \(56.9\%\), which is more than twice the error in any other benchmark model. This result is intuitive. Model (b) presumes time-invariant value drivers and is insensitive to intertemporal shifts in the size of the units. All other models separately forecast both units’ accounting measures and are at least partially able to depict their long-term development. The error of benchmark model (b) is particularly sensitive to the ROICs of both units (\(15.5\%\) and \(-3.5\%\) in units A and B, respectively): According to Proposition 1, \(ROIC^A\) and \(ROIC^B\) determine the long-term ROIC and have a crucial influence on the misspecification in (19).Footnote 28

Benchmark model (c) causes the highest mean valuation error of \(6.4\%\). This model is characterized by two misspecifications. First, it does not consider any growth in unit A. This generally causes undervaluation. The corresponding error is most severe if the ROIC and intra-unit investment rate of unit A are high, as both parameters jointly determine the growth rate \(g^A = n^A \cdot ROIC^A\). Second, the cross-unit investment rate is equalized with the intra-unit investment rate of unit B. This further aggravates the undervaluation if the actual cross-unit investment rate is higher than this intra-unit investment rate, \(n^{AB} > n^B\). By contrast, the model tends to overstate the terminal value if the net investment rate exceeds the cross-unit investment rate. In our numerical setting, most observations satisfy the condition \(n^{AB} > n^B\). Therefore, the majority of valuation outcomes are too low (\(96.9\%\)). The error is aggravated for increasing \(n^{AB}\) and decreasing \(n^{B}\) (with corresponding sensitivities of \(69.9\%\) and \(-2.4\%\)). Such variations aggravate the misspecification for the majority of our observations.

The valuation outcome of benchmark model (d) is based on a fictitious cross-unit investment rate \((g^B - g^A)/(ROIC^B - g^A)\) that ensures constant growth of the free cash flow. If the cross-unit investment rate \(n^{AB}\) exceeds this threshold, the benchmark model implies undervaluations. For our numerical example, this is the case for \(82.7\%\) of the population. This error is aggravated if the cross-unit investments in unit B are important, that is, if this unit yields a high return. Therefore, \(ROIC^B\) has considerable impact on the error with a sensitivity of \(7.2\%\). The mean relative valuation error of model (d) is \(4.7\%\).

Altogether, the simulation analysis shows that our model is particularly useful in improving valuation precision if firms plan considerable cross-unit investments. Thus, the simulation analysis confirms the high relevance of a correct representation of value-creating cross-unit investments as an essential aspect of business unit strategy (Solomons 1965; Kontes 2010). Moreover, the benefits of our valuation approach are high if firms exhibit low cost of capital and if subsidized business units yield a high return. In the latter case, the value contribution of cross-unit investments should be estimated more precisely.

5 Implications for corporate valuation theory and practice

In this study, we develop a terminal value model that is based on a firm’s strategy formulation at the business unit level. We consider a setting with heterogeneous business units and show the implications of (intra- and cross-unit) investments for i) the long-term development of the firm’s accounting measures and ii) the terminal value of the firm. The framework with two business units generalizes existing work and can easily be extended to more than two business units. We further characterize strategy choices that cause constant payout ratios and constant growth of the free cash flow. Our results contribute to the valuation literature in several ways.

Our model extends the valuation approaches of Koller et al. (2015) and Meitner (2013), who impose additional assumptions on a firm’s cross-unit investments. Such investments are essential if firms try to manage the long-term development of their business portfolio (Solomons 1965; Kontes 2010). Valuation approaches should offer sufficient degrees of freedom to depict firms’ plans to (re-)allocate budgets among business units. We develop discounted cash flow and a residual income approaches that allow for arbitrary cross-unit investment rates and show how business unit strategies translate into firm value.

Moreover, our model framework allows us to study how value drivers affect expectations about a firm’s future accounting measures. We delineate expected invested capital, free cash flow, and residual income as a function of the investment strategy and business unit rentability. We also illustrate the long-term development of the total ROIC and payout ratio. Management can use these results to review the plausibility of their planning assumptions. Managers frequently pursue long-term targets on the aggregate level such as target payout ratios or growth rates. Our results can be used to reconcile such long-term targets with the strategy formulation at the business unit level. In addition, we study under which conditions a business unit strategy implies constant payout ratios and constant growth of the aggregate free cash flow – strategies that have high practical relevance and are frequently considered in alternative valuation models. A special case that is characterized by both constant payout ratios and constant growth of the free cash flow can only occur if the firm’s business units exhibit identical ROIC. Therefore, the application of the value driver model by Gordon and Shapiro (1956) is limited to settings with homogenous business units. This finding is remarkable given the prominent role of the value driver model in valuation practice. Our results challenge the assumption of uniform value drivers in analyzing and valuing firms that operate in multiple business areas.

We highlight the usefulness of our results for external parties such as financial analysts and investors who do not have access to strategy information. Given financial disclosures about a firm’s operating segments, external parties learn about a firm’s investment strategy and future business model (Kang et al. 2017). Our results offer a simple way to estimate the relevant value drivers and to use them in fundamental analysis and firm valuation. Hence, our results are useful not only for the management’s endeavors to identify and substantiate value-increasing strategies, but also for deciphering firm disclosures on the long-term development of a firm’s accounting measures. We further use a simulation study to illustrate that such efforts may be worthwhile. If we assume that firm strategy can be depicted by our valuation model, alternative valuation formulas yield significant errors. The relative precision of our model is particularly high in cases of considerable cross-unit investment rates and high rentability of the business units that are subsidized. Under these conditions, the valuation formulas identified in this paper may be particularly useful although they are associated with slightly higher complexity.

Finally, our results on the relations of forecasts at the firm and business unit level relate to empirical work on value creation. We provide insights on the interplay of value drivers, accounting measures, and firm value, which may be useful for work on the interrelation of accounting characteristics and value (Penman et al. 2018). Other empirical studies identify a diversification discount that is partly related to firms’ cross-subsidization of under-performing business units (Rajan et al. 2000). Our study helps in estimating the value gains and losses associated with cross-unit investments and may therefore be useful in establishing transparency with regard to the financial consequences of firm diversification.

Our results are subject to several limitations. First, we do not consider differences in the business units’ cost of capital. This is arguably a legitimate simplification in various practical settings. Yet, there are firms that operate in multiple markets and face substantial differences in operational risk. Firms may also define specific financing strategies for their business units to address different liquidity requirements and tax treatments. The additional consideration of heterogeneous operational and financial risks could therefore be a useful extension of our model. Moreover, our valuation model relies on forecasts of the ROIC and investment rates. Such value driver models have shortcomings in valuing firms in technology and knowledge-based industries that heavily rely on intangible assets. Our model requires estimates of invested capital and ROIC not only at the firm level but also at the business unit level and is therefore prone to estimation errors. Additional refinements and alternative value drivers may be helpful in mitigating these errors. Finally, we focus on cross-unit investments in multi-business organizations. Aside from cross-unit investments, there may be other types of interdependencies such as the joint use of non-financial resources or product market interactions. All in all, our analysis provides a sound theoretical basis for further research on the valuation of diversified firms.

Notes

The literature has developed extensions of this model aiming for a more general depiction. For example, cash flows follow a long-term adjustment process based on the convergence of returns or growth rates (O’Brien 2003; Elton et al. 2014). For an overview and critical discussion see Elton et al. (2014), Palepu et al. (2019), and Schwetzler (2019).

This problem is closely related to the aggregation of relative performance indicators such as return on investment which has been discussed extensively in the accounting literature (Jacobson 1987).

Aside from cross-unit investments, there may be other types of interdependencies that we do not consider such as the joint use of non-financial resources or product market interactions (Solomons 1965).

In a similar model setup, Daves et al. (2004) assume an exogenously given growth rate of the total invested capital that is unrelated to business unit profitability. This assumption lacks theoretical foundations. It is unclear whether it can be aligned with established model premises: Models of corporate investment typically assume that firms’ financial surpluses correspond to those of a sequence of structurally identical investment projects (Friedl and Schwetzler 2011; Penman 2013).

Following previous literature, we do not consider a division into more than two business units (Meitner 2013; Koller et al. 2015). This simple case is sufficient to illustrate our results, which can easily be extended to a firm with more business units. Note that we do not discuss the optimal trade-offs in establishing multiple business units. Such results are clearly beyond our analysis, which focuses on the precision of valuation models. We do not discuss the benefits of more precise information for managers and investors.

In line with other literature on corporate valuation, we do not study optimal strategy choice. Yet, our results may be used to illustrate the effects of alternative investment strategies. An analysis of optimal strategies requires a more comprehensive model, for instance considering costs of financial distress.

Given the detailed information, determining the value in the explicit forecast period is less challenging from a theoretical perspective.

The tilde \((\widetilde{\,\cdot \,})\) denotes variables that are random at the time of valuation. An overview of mathematical symbols used in our study is provided in Appendix A.

Although it seems convenient to assume that firms reallocate resources from units with low rentability to more profitable units, empirical studies document that the opposite might be true (Rajan et al. 2000).

Note that business unit rentability and the investment strategy are not mutually independent. Intuitively, capital rationing motivates business unit managers to invest into the most profitable projects and increases the expected return on investment. We do not discuss the relation of the investment rates and returns but assume that the input data of the valuation has been chosen in a consistent way.

We focus on one-directional cross-unit investments from unit A to unit B. An extension of our model to mutual cross-unit investments can easily be achieved, but is economically questionable.

We add the superscripts A or B to indicate that a variable relates to this unit. The variables at the firm level are used without superscript, that is, \(E[\tilde{x}_t] = E[\tilde{x}_t^A] + E[\tilde{x}_t^B]\) for \(x \in \left\{ IC, NI, NOPLAT, FCF \right\}\).

The benchmark models are presented as discounted cash flow calculus. In Appendix B, we provide the corresponding valuation formulas in a residual income approach.

We implicitly assume that the cost of capital exceeds both units’ growth rates (i.e., \(k > g^i\)), which is not a major limitation given realistic parameter ranges.

Meitner (2013) uses his model to illustrate potential benefits of cash flow- compared with accounting-based valuation models. Our results hint at limitations of the value driver model in depicting intra-firm heterogeneity. Yet, we do not focus on the comparison of cash flow- and accounting-based valuation models.

All proofs are provided in Appendix C. A more detailed technical appendix is available upon request.

Benchmark models (c) and (d) assume that \(g^B \ge g^A\). Therefore, the long-term development of the firm is completely aligned with that of unit B. Proposition 1 highlights cases where the limiting values of the total ROIC and payout ratio reflect the value drivers of both units. This is the case if the firm shifts budgets from units with high growth rates to units with lower growth rates.

Empirical work shows that investors and analysts use segment reports and that the precision of their forecasts depends on segment reporting standards; see Baldwin (1984), Berger and Hann (2003), and Kang et al. (2017). Moreover, managers are aware of the external use of segment information and strategically bias reports, see Wang et al. (2011), You (2014), and Haight (2019).

Interestingly, most of the CFOs who participate in this survey admit that they would forgo value maximization to smooth earnings (Graham et al. 2005).

We study a payout ratio that relates to the firm’s NOPLAT and therefore, defines both shareholders’ and debtholders’ claims against the firm.

For \(n^A > n^B\), a constant payout strategy according to Proposition 3 (a) implies a negative cross-unit investment rate, which is questionable from an economic viewpoint.

To exclude the economically unreasonable result of negative cross-unit investment rates, we require that \(g^B \ge g^A\). Note that this restriction implies \(ROIC^B > g^A\).

The growth rates in our sample lie within the range \([0.45\%; 2\%]\). Our assumptions reflect realistic ranges for the ROICs and growth rates of the business units (Koller et al. 2015).

This limits the comparability of the simulation results across the different models. Yet, the insights from the simulation analysis do not change if we apply all models to the same data set.

This argument is substantiated by the simulation results. We compare the ROIC according to (19) with the long-term ROIC and measure the relative misspecification error \((ROIC - ROIC^\infty )/ROIC^\infty\) . This error has a small mean of \(0.2\%\) but a high standard deviation of \(9.5\%\). The variation in the misspecification error can be largely explained by the ROICs of the units A and B with sensitivities of \(50.0\%\) and \(-49.9\%\).

References

Arzac ER (2008) Valuation for mergers, buyouts, and restructuring, 2nd edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Baldwin BA (1984) Segment earnings disclosure and the ability of security analysts to forecast earnings per share. Acc Rev 59(3):376–389

Berger PG, Hann R (2003) The impact of SFAS No. 131 on information and monitoring. J Acc Res 41(2):163–223

Berger PG, Ofek E (1995) Diversification’s effect on firm value. J Financ Econ 37(1):39–65

Bradley M, Jarrell GA (2008) Expected inflation and the constant-growth valuation model. J Appl Corp Financ 20(2):66–78

Brav A, Graham JR, Harvey CR, Michaely R (2005) Payout policy in the 21st century. J Financ Econ 77(3):483–527

Damodaran A (2005) Valuation approaches and metrics: a survey of the theory and evidence. Found Trends Financ 1(8):693–784

Daves PR, Ehrhardt MC, Shrieves RS (2004) Corporate valuation: a guide for managers and investors, 4th edn. Cengage Learning, Boston

Elton EJ, Gruber MJ, Brown SJ, Goetzmann WN (2014) Modern portfolio theory and investment analysis, 9th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Friedl G, Schwetzler B (2011) Terminal value, accounting numbers, and inflation. J Appl Corp Financ 23(2):104–112

Fuller RJ, Kerr HS (1981) Estimating the divisional cost of capital: an analysis of the pure-play technique. J Financ 36(5):997–1009

Gordon MJ, Shapiro E (1956) Capital equipment analysis: the required rate of profit. Manage Sci 3(1):102–110

Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2005) The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J Acc Econ 40(1):3–73

Haight TD (2019) Earnings shortfalls and strategic profit allocations in segment reporting. Acc Horizons 33(4):37–58

Harris RS, Pringle JJ (1985) Risk-adjusted discount rates — extensions from the average-risk case. J Financ Res 8(3):237–244

Hoechle D, Schmid M, Walter I, Yermack D (2012) How much of the diversification discount can be explained by poor corporate governance? J Financ Econ 103(1):41–60

Imam S, Barker R, Clubb C (2008) The use of valuation models by UK investment analysts. Eur Acc Rev 17(3):503–535

Ittner CD, Larcker DF (2001) Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. J Acc Econ 32(1):349–410

Jacobson R (1987) The validity of ROI as a measure of business performance. Am Econ Rev 77(3):470–478

Kang T, Khurana IK, Wang C (2017) International diversification, SFAS 131 and post-earnings-announcement drift. Contemp Acc Res 34:2152–2178

Koller T, Goedhart M, Wessels D (2015) Valuation: measuring and managing the value of companies, 6th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Kontes P (2010) The CEO, strategy, and shareholder value. Wiley, Hoboken

Lewellen WG (1971) A pure financial rationale for the conglomerate merger. J Financ 26(2):521–537

Majd S, Myers SC (1987) Tax asymmetries and corporate income tax reform. In: Feldstein Martin (ed) Effects of taxation on capital accumulation. Elsevier, Chicago, pp 343–376

Meitner M (2013) Multi-period asset lifetimes and accounting-based equity valuation: take care with constant-growth terminal value models!. Abacus 49(3):340–366

Miles JA, Ezzell JR (1980) The weighted average cost of capital, perfect capital markets, and project life: a clarification. J Financ Quant Anal 15(3):719–730

Miles JA, Ezzell JR (1985) Reformulating tax shield valuation: a note. J Financ 40(5):1485–1492

O’Brien TJ (2003) A simple and flexible DCF valuation formula. J Appl Financ 13(2):54–62

Palepu KG, Healy PM, Peek E (2019) Business analysis and valuation - IFRS edition, 5th edn. Cengage Learning, Andover

Penman SH (2013) Financial statement analysis and security valuation, 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, Boston

Penman SH, Reggiani F, Richardson SA, Tuna I (2018) A framework for identifying accounting characteristics for asset pricing models, with an evaluation of book-to-price. Eur Financ Manag 24(2):488–520

Plenborg T (2002) Firm valuation: comparing the residual income and discounted cash flow approaches. Scand J Manag 18(3):303–318

Rajan R, Servaes H, Zingales L (2000) The cost of diversity: the diversification discount and inefficient investment. J Financ 55(1):35–80

Rappaport A (1997) Creating shareholder value: a guide for managers and investors, 2nd edn. Free Press, New York

Reichelstein S (1997) Investment decisions and managerial performance evaluation. Rev Acc Stud 2(2):157–180

Schwetzler B (2019) Unternehmensbewertung und Terminal Value - Konvergenz von Wachstumsraten, Renditen oder Assets? Corp Financ 6(1–2):57–65

Solomons D (1965) Divisional performance. Measurement and control, Irwin, Homewood

Stone B (1972) The use of forecasts and smoothing in control-limit models for cash management. Financ Manag 1(1):72–84

Titman S, Martin JD (2011) Valuation: the art and science of corporate investment decisions, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Boston

Wang Q, Ettredge M, Huang Y, Sun L (2011) Strategic revelation of differences in segment earnings growth. J Acc Public Policy 30(4):383–392

You H (2014) Valuation-driven profit transfer among corporate segments. Rev Acc Stud 19:805–838

Young SD, O’Byrne SF (2001) EVA and value-based management: a practical guide to implementation. McGraw-Hill, New York

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ralf Diedrich, Michael Ebert, Christoph Kuhner, Helmut Maltry, Burkhard Pedell, Stephen Penman and participants at the 39th Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association and the 79th Annual Meeting of the VHB for their helpful comments on prior versions of this paper.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: overview of mathematical symbols

\(a^x\) | Absolute valuation error of model \(x \in \{ a,b,c',d'\}\) |

\(E[\widetilde{FCF}_t^i]\), \(E[\widetilde{FCF}_t]\) | Free cash flow of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm) at time \(t\ge 1\) |

\(g^i\) | Growth rate within unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\); \(g^i = n^i \cdot ROIC^i\) |

\(g^x_t\) | Growth rate of \(x \in \{IC,NI,NOPLAT,FCF\}\) in period \(t\ge 1\) |

\(E[\widetilde{IC}_t^i]\), \(E[\widetilde{IC}_t]\) | Invested capital of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm) at time \(t\ge 0\) |

k | Weighted average cost of capital |

\(\lambda ^{ROIC}\), \(\lambda ^{q}\) | Weights in the limit of the total ROIC and payout ratio |

\(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^i]\), \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0]\), \(E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^{AB}]\) | Stand-alone MVA of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm/ the cross-unit investments) |

\(n^i\) | Intra-unit investment rate of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) |

\(\overline{n}^{AB}\), \(n^{AB}\) | Cross-unit investment rate related to the NOPLAT (after intra-unit investments) of unit A |

\(E[\widetilde{NI}_t^i]\), \(E[\widetilde{NI}_t]\) | Net investments of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm) at time \(t\ge 1\) |

| NOPLAT of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm) at time \(t\ge 1\) |

\(p^x\) | Relative valuation error of model \(x \in \{ a,b,c',d'\}\) |

\(q_t\), \(q^\infty\) | (Long-term) payout ratio of the firm at time \(t \ge 1\) |

\(E[\widetilde{RI}_t^i]\), \(E[\widetilde{RI}_t]\) | Residual income of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm) at time \(t\ge 1\) |

\(ROIC^i\), \(ROIC_t\), \(ROIC^\infty\) | (Long-term) return on invested capital of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm at time \(t \ge 1\)) |

\(s^x\) | Sign of the valuation error with model \(x \in \{ a,b,c',d'\}\) |

\(E[\widetilde{V}_0^i]\), \(E[\widetilde{V}_0]\), \(E[\widetilde{V}_0^{AB}]\) | Stand-alone value of unit \(i\in \{A,B\}\) (the firm/ cross-unit investments) |

\(E[\widetilde{V}_0^x]\) | Terminal value with model \(x \in \{ a,b,c,c',d,d'\}\) |

\(E[\widetilde{V}_0^{cp}]\), \(E[\widetilde{V}_0^{cg}]\) | Terminal value with a constant payout (growth) strategy |

1.1 Appendix B: benchmark models based on residual income

Benchmark model (a) | \(E[\tilde{V}_0^a] = E[{\widetilde{IC}_0}] + \underbrace{\textstyle \frac{ROIC^A - k}{k - g^A} \cdot E[\widetilde{IC}_0^A]}_{ = E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^A]} + \underbrace{\textstyle \frac{{ROI{C^B} - k}}{{k - {g^B}}} \cdot E[\widetilde{IC}_0^B]}_{ = E[\widetilde{MVA}_0^B]}\) |