Abstract

Understanding the antecedents of social entrepreneurship is critical for unleashing the potential of social entrepreneurship and thus for tackling social problems. While research has provided valuable insights into imprinting of the conventional entrepreneur, research on differences between social and conventional entrepreneurship suggests that social entrepreneurs evolve differently. Using survey data of 148 social entrepreneurs, we draw on the concepts of imprinting and critical incident recognition as a framework for understanding how social entrepreneur’s childhood experiences and parental exposure to social entrepreneurship affect social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. First, our results suggest that social entrepreneurs are imprinted by their childhood experiences but not by parental exposure to social entrepreneurship. Second, imprints tend to persist over time when they are linked to critical incidents regarding social entrepreneurship. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of imprinting mechanisms in social entrepreneurship contexts and highlight the importance of making examples of social entrepreneurship tangible to children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social entrepreneurship is increasingly valued as an effective means to tackle challenges such as climate change, digitization of operations and its social impacts, modern slavery, or the development towards a circular economy (Lumpkin et al. 2018; Rahdari et al. 2016; Saebi et al. 2019). Defined as “a process by which citizens build or transform institutions to advance solutions to social problems, such as poverty, illness, illiteracy, environmental destruction, human rights abuses and corruption, in order to make life better for many” (Bornstein and Davis 2010, p. 1), social entrepreneurship opens a unique and intriguing empirical context for the study of entrepreneurship phenomena (Parkinson and Howorth 2008). Consequently, social entrepreneurship has been receiving more attention in research (e.g. Kuhn and Weibler 2011; Schreck 2011; Salzmann 2013; Kraus et al. 2014; Phillips et al. 2014) and has been found to serve as a scalable role model for sustainable operations (Narang et al. 2014). Additionally, more and more corporations, such as the German producer of utility vehicles, MAN, aim at improving their reputation and CSR performance through stimulating social entrepreneurship. Still, a surprising lack of understanding of the drivers of social entrepreneurial activity exists (Hoogendoorn 2016). Particularly, how social entrepreneurs emerge remains unclear (Chandra and Shang 2017). Parkinson and Howorth (2008, p. 286) stress that knowledge on the antecedents of social entrepreneurship is of utmost importance because “without an understanding of why people engage in social entrepreneurship […], policies aimed at supporting the sector may be flawed”.

To overcome our limited understanding of social entrepreneurs’ emergence, Dacin et al. (2011) propose exploring existing theories in the context of social entrepreneurship. Indeed, some theoretical approaches have been adopted in social entrepreneurship research, for example personality-trait theory (e.g. Nga and Shamuganathan 2010; Miller et al. 2012) or the theory of planned behavior (e.g. Forster and Grichnik 2013; Politis et al. 2016). However, Hockerts (2017) highlights that theoretical approaches such as personality-trait theory, do not allow for identifying factors that can be manipulated (e.g. by education or political interventions), as personality traits are rather stable. In contrast, a burgeoning body of research in entrepreneurship has explored the enduring impact of past critical events on individual outcomes in the present and in the future, thereby accentuating imprinting theory (Marquis and Tilcsik 2013; Mathias et al. 2015). Imprinting theory offers a promising perspective, as it facilitates identifying antecedents of social entrepreneurship that can be manipulated, thereby allowing active support for the emergence of social entrepreneurship.

Mathias et al. (2015, p. 12) define “imprinting as a time-sensitive (…) learning process (…) that initiates a development trajectory”. Imprinting theory suggests that during sensitive periods, an individual’s cognitive models, norms, and values are highly susceptible to environmental forces (Mathias et al. 2015). Hence, during periods of cognitive unfreezing, formative experiences can shape entrepreneurial behavior durably. These formative experiences can stem from different sources, which Mathias et al. (2015) term sources of imprint. While most extant research deals with sources of imprint that occur in adulthood (e.g. Higgins 2005; McEvily et al. 2012), Marquis and Tilcsik (2013) highlight that further sensitive periods and further sources of imprints need to be considered. Existing studies in entrepreneurship have identified a range of sources of imprints and temporal phases of life (e.g. childhood, young adulthood) in which individuals are indelibly shaped by their environment (e.g. Mathias et al. 2015). However, it has not been researched whether some phases in life, such as childhood, are indeed more crucial time periods for certain imprints that are particularly relevant for social entrepreneurship.

Beyond imprinting processes, critical incidents, in terms of discontinuous and highly emotional experiences, have been identified as an important factor in influencing entrepreneurial activity (e.g. Cope and Watts 2000; Yiu et al. 2014; Mathias et al. 2015). In the context of entrepreneurial learning and training, critical incidents help participants to learn how to deal with risk and uncertainty in an entrepreneurial way (Minniti and Bygrave 2001). It has been argued that individuals not only learn from critical event recognition, but also develop their ability to think and act like entrepreneurs based on that experience (Cope and Watts 2000). However, the influence of critical incident recognition on social entrepreneurial activity, as well as their relevance for the imprinting process, has not yet been explored sufficiently.

Focusing on imprinting and critical incident recognition during childhood, this paper analyzes the emergence of social entrepreneurial activity on an individual level. Hence, this study addresses the following research questions: (1) How do sources of imprints during childhood influence social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood? (2) Does the recognition of critical incidents in childhood moderate the relationship between sources of imprints during childhood and social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood?

By addressing these research questions, we extend the discussion on imprinting in the context of social entrepreneurship to additional sensitive periods (i.e. childhood) and additional sources of imprints (i.e. own experiences, parental exposure to social entrepreneurship) upon individuals. Further, by introducing critical incidents to the debate, we investigate when sources of imprints during childhood exert a long-lasting effect. We build on quantitative data from an online survey of 148 social entrepreneurs to test our hypothesis. The results of a moderated regression analysis with bootstrapping indicate a positive influence from social entrepreneur’s childhood experiences on social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. This effect is leveraged by critical incident recognition regarding social entrepreneurship. When social entrepreneur’s childhood experiences coincide with the recognition of a critical incident, they open up a window of opportunity for imprinting, leading to a higher level of social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood.

Our research contributes to social entrepreneurship literature in three distinct ways. First, this study extends research on the emergence of social entrepreneurs by investigating how an individual’s background and childhood experiences influenced their social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. Several studies have confirmed that individuals make their career choices at a relatively early stage (Furlong and Biggart 1999; Byrne et al. 2012) and that in these early stages, individuals’ cognitions are especially susceptible to influences of others (Bandura 1986). Therefore, we extend imprinting theory by connecting imprinting forces during childhood to social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. Second, our research contributes to the discussion on imprinting on the individual level by investigating the effect of imprints on social entrepreneurs, as opposed to imprinting effects on an organization (cf. Ellis et al. 2017; Simsek et al. 2015). Previous research rarely investigated early imprinting at the individual level, missing important micro-level factors that predict the extent and potency of imprinting (Simsek et al. 2015). Third, we integrate the recognition of critical events into the imprinting process, thereby advancing the debate on why some individuals display imprinting effects while others do not (Tilcsik 2014). To date, extant research has emphasized the role of imprinting in entrepreneurial activity (Lee and Battilana 2013; Mathias et al. 2015) but falls short in explaining under which circumstances the individual’s imprintability toward formative experiences proves to be particularly high.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1 Antecedents of social entrepreneurship and imprinting

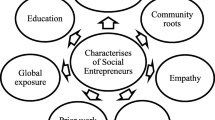

While considerable attention has been paid to the antecedents of conventional entrepreneurial activity and the characteristics of entrepreneurs, Prieto et al. (2012) claimed that the antecedents of social entrepreneurial activity and the characteristics of social entrepreneurs are under-researched (cf. Mair and Martí 2006; Miller et al. 2012; Sastre-Castillo et al. 2015). Defourny and Nyssens (2008: 4) define social entrepreneurs as “individuals launching new activities dedicated to a social mission while behaving as true entrepreneurs […]”. As Bacq et al. (2016: 703) point out, it is indeed their “intention and dominance of perceived social value creation over economic value creation” that makes social entrepreneurs unique. Specifically, social entrepreneurs distinguish themselves from their commercial counterparts in their motivations and intentions of actively doing good for society (Dacin et al. 2010; Zahra et al. 2009).

The existing studies in this field mostly refer to the personality-trait approach (e.g. Nga and Shamuganathan 2010; Miller et al. 2012; Forster and Grichnik 2013) or intention-based models such as the theory of planned behavior (e.g. Forster and Grichnik 2013; Politis et al. 2016; Hockerts 2017). Further research on the antecedents of social entrepreneurship reveal a positive influence from economic, social and entrepreneurial skills on social entrepreneurial activity (e.g. Lepoutre et al. 2013; Scheiber 2016; Chandra and Shang 2017; Hechavarría et al. 2017). In contrast to intention-based or personality-trait models, imprinting theory has gained only limited attention in social entrepreneurship research so far. Imprinting occurs during sensitive phases in life, in which elements of the environment are “stamped” upon a focal entity and persist against further environmental changes. Imprinting theory posits that it is possible to imprint a certain propensity for entrepreneurship upon an individual. This can be conveyed through either direct experience with imprinting forces or indirect social mechanisms such as role models and strategic education (Marquis and Tilcsik 2013; Jaskiewicz et al. 2015). Diverse imprinting sources, such as family members (Aldrich and Kim 2007; Jaskiewicz et al. 2015; Suess-Reyes 2017), mentors (Azoulay et al. 2017), faculty members (Bercovitz and Feldman 2008), and institutional conditions (Higgins 2005; Dokko et al. 2009) have been identified. Research has demonstrated how imprinting processes shape individuals’ career choices (Higgins 2005; McEvily et al. 2012; Azoulay et al. 2017). Particularly during periods of career transition, individuals experience high levels of anxiety and cognitive unfreezing due to high degrees of novelty and uncertainty during these periods (Higgins 2005; Marquis and Tilcsik 2013). Under such circumstances, observing and comparing the behavior of peers, mentors, and leaders guide individuals toward reducing anxiety by obtaining “powerful cues as to how to behave” (Higgins 2005, p. 338).

In the context of social entrepreneurship, Lee and Battilana (2013) analyze how founders of social enterprises are subject to commercial imprints. They find three sources of such imprints, that is, the founders’ work experience, professional education and the work experience of the founders’ parents. Battilana et al. (2015) examine organizational factors that influence social and economic performance. Their results show that while social imprinting, in terms of a founder’s early emphasis on the social mission, improves an organization’s social performance, it exerts a negative influence on economic performance. In addition, on an organizational level of analysis, Siqueira et al. (2018) use imprinting theory to analyze how capital structure differs between social and commercial enterprises. They find support for the proposed differences and explain these differences based on the imprints of pro-social organizing. This brief summary shows that imprinting theory so far has been applied only sparsely in social entrepreneurship research and is concentrated on imprinting forces on the organizational, but not on the individual, level.

2.2 Sensitive periods and individual imprinting

Imprinting research shows that individuals are likely to experience several sensitive periods throughout their lives (Marquis and Tilcsik 2013). Therefore, it is important to determine during which periods individuals are most receptive to imprinting forces. Imprinting scholars agree that sensitive phases coincide with periods of transition, induced by a triggering event (Marquis and Tilcsik 2013; Simsek et al. 2015). Systematic analysis of transition periods in adulthood regarding work experience led to a better understanding of individual career paths (Higgins 2005; McEvily et al. 2012).

However, sensitive periods can also occur early during an individual’s lifetime. Psychologists (Bruhn 1985) as well as social psychologists (Bruner 2003) reveal the importance of childhood experiences in individual imprinting by probing their patients’ earliest memories as the first symbol of the self and a blueprint as to who a person becomes. Focusing on specific emotional events before the age of ten rather than on more generic memories (Bruhn 1985), earliest memories provide a projective tool to experiences that are the foundation for the self-concept (Bruner 2003). Indeed, several studies have confirmed that individuals make their career choices during relatively early life stages (Furlong and Biggart 1999; Byrne et al. 2012) and highlighted the importance of early experiences on an individual’s values and pro-social behavior (Kosse et al. 2020). Further, it has been shown that the memory of group experiences during childhood influences volunteering behavior in adulthood (Marzana et al. 2015). Extant literature on entrepreneurial intentions considered that attitudes toward starting a business might develop early in life, that is, during childhood experiences (e.g. Laspita et al. 2012; Jaskiewicz et al. 2015). Mathias et al. (2015) find that individuals are more likely to be intrigued by entrepreneurial pursuits and thus will be more likely to take entrepreneurial action when the intent to become an entrepreneur is imprinted on them early in life. Altogether, these findings illustrate that individuals are subject to time-sensitive periods during childhood, as children generally are more receptive to learning (in terms of an imprinting process).

2.3 Prior experience, critical incidents, and their influence on entrepreneurial activity

Entrepreneurship research considers an individual’s prior experience to be important antecedents of entrepreneurial activity. According to Marquis and Tilcsik (2013), personal experience is crucial to imposing an imprint on individuals. During sensitive periods, individuals are subject to a process of cognitive unfreezing, in which they learn and adopt norms, cognitive models, and behaviors from their environments (Tilcsik 2014; Azoulay et al. 2017). Types of experiences analyzed include educational experience (Tracey and Phillips 2007; Martin et al. 2013), work experience (Higgins 2005; McEvily et al. 2012), and experience of past entrepreneurial success (Jaskiewicz et al. 2015), among other life experiences (e.g. Corner and Ho 2010; Scheiber 2016).

Regarding social entrepreneurship, Hockerts (2017) finds that prior experience with social organizations and social problems is positively related to social entrepreneurial intent. His findings further reveal a relation between students’ prior experience with social problems and their self-efficacy, that is, their belief in their own capabilities to perform a task. These results suggest that individuals imprinted by social-entrepreneurship experience are more likely to become social entrepreneurs whereas individuals who lack prior experience with social entrepreneurship are less likely. Additionally, research shows that experiences in childhood lay the path for an individual’s decision-making and values during adulthood (Furlong and Biggart 1999; Byrne et al. 2012; Laspita et al. 2012; Jaskiewicz et al. 2015). Therefore, we set up the following first hypothesis:

H1

Personal experience with social entrepreneurship during childhood imprints social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood.

In addition to personal experiences, entrepreneurial behavior also can be imprinted by the social context (Tilcsik 2014). Across different sources of social influence, family and parents have received the most attention in entrepreneurship research (e.g., Aldrich and Kim 2007; Eesley and Wang 2017; Suess-Reyes 2017). Laspita et al. (2012) show how parents and grandparents’ narratives about their former businesses shape the entrepreneurial intentions of their grandchildren. Likewise, parents give meaning to the concept of entrepreneurship through rhetorically reconstructed narratives of their own past entrepreneurial behavior (Jaskiewicz et al. 2015). Insights from psychological research underpin these findings. According to Pillemer (1998), parent–child-attachments form during sensitive periods, making children’s memory processes susceptible to the influence of their parents. During these sensitive periods, experiences with significant others (e.g. parents and grandparents) become encoded into implicit memory and serve as expectations that help children construct their frame of reference.

In line with these findings, imprinting theory posits that a propensity for entrepreneurship can be imprinted upon an individual indirectly through social mechanisms (Marquis and Tilcsik 2013). Carr and Sequeira (2007) find that children will have a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship if they perceive that relevant reference individuals and groups in their lives, such as family members, hold such attitudes. Parents might transmit entrepreneurial values, skills, and behavioral cues in a conscious and unconscious manner (Laspita et al. 2012). Since parents constitute an initial and long-lasting social-reference group for a child (Lee and Battilana 2013), parent–child interactions provide children with a frame of reference for self-evaluation and shared identity formation. Furthermore, the parent–child relationship is infused with a deeper and more prolonged level of social influence (captured in terms of exposure) relative to other sources of influence (Eesley and Wang 2017; Sørensen 2007). For example, parents pass their entrepreneurial experience rhetorically through narratives and storytelling, thereby motivating children and providing positive meaning to their understanding of entrepreneurship. Families nudge their children toward entrepreneurial work experience, fostering imprinting through childhood involvement in the family business (Jaskiewicz et al. 2015). Some studies argue that parental influence operates through “exposure” mechanisms in that children exposed to self-employed parents are more likely to look at self-employment as a legitimate “alternative to conventional employment” (Carroll and Mosakowski 1987, p. 576). Mathias et al. (2015, p. 19) conclude that “those individuals exposed to entrepreneurship at a young age, particularly through family, are repeatedly willing to take on new challenges by pursuing new businesses”.

As Lee and Battilana (2013) point out, parenting interactions not only imprint children toward specific types of work, but also toward pro-social activities similar to those of their parents. Forster and Grichnik (2013) note that voluntary behavior is spurred if individuals perceive that important people in their lives consider volunteering to be important. Likewise, in the context of pro-social behavior among Canadian youths, Pancer and Pratt (1999) find that parents’ social influence is among the initial factors that lead to volunteering. Hence, children of entrepreneurs, or children of socially engaged parents, are encouraged to import entrepreneurship or social responsibility, respectively, into their self-concepts. Based on these earlier findings, we present our second hypothesis:

H2

Parental exposure to social entrepreneurship during childhood imprints social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood.

In Hypotheses 1 and 2, we expect that personal experiences and parental exposure to social entrepreneurship influence social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. However, extant literature suggests that some experiences impart only a temporary influence on individuals, while others endure and alter individuals’ cognitive frames (Politis 2005), as well as shape their entrepreneurial mindset (McGrath and MacMillan 2000). Thus, an individuals’ imprintability, that is its’ receptivity towards imprinting, can vary. Tilcsik (2014), for example, suggests that prior work experience reduces the strength of imprinting during socialization. This raises the question of which factors influence an individuals’ imprint-ability as our understanding of circumstances under which an experience remains formative to entrepreneurs is limited (Martin et al. 2013).

In this context, Mathias et al. (2015) as well as Breugst et al. (2015) emphasize critical incidents in the entrepreneur’s early lived experience that continue to manifest themselves in an enduring way throughout their life history. Cope and Watts (2000) refer to critical events as salient moments or discontinuous experiences of prime importance. Although critical events tend to be perceived as negative experiences, Snell (1992) emphasizes that learning is promoted exceptionally during difficult situations. In line with this finding, Ellis et al. (2006, p. 670) interpret critical events as the “fuel that intensifies cognitive processes”, thereby altering cognitive frames and mental models that govern subsequent action. Cope and Watts (2000, p. 114) add that a critical incident is “essentially an emotional event” that arouses intense feelings and involvement with critical experiences. In a qualitative study on the causes of social entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurs pointed to significant events that provided direct exposure to circumstances (for example, visiting developing countries, living in inner cities) and that differed significantly from their familiar environments (Shumate et al. 2014). Those critical events not only “triggered a major change in the trajectory of their life”, but also “directly informed the type of social venture they formed” (Shumate et al. 2014, pp. 411–412). Researching antecedents of social entrepreneurship in China, Yiu et al. (2014) find that certain stressful experiences in the past (for example, rural poverty or unemployment) predict social entrepreneurial behavior. Likewise, comparing social entrepreneurs to high-tech entrepreneurs, Yitshaki and Kropp (2016) identify (disruptive) life events as a trigger of social activity.

In search of a better understanding of the impact of critical events on entrepreneurial learning, Cope and Watts (2000) conducted interviews with six small-business owners to examine how they entered the business realm. The results unveil that critical incidents constitute powerful learning events for entrepreneurs. Exploring how individuals change their thoughts and actions in response to critical events, Lindh and Thorgren (2016) find that individuals recognize strong emotions caused by critical incidents and subsequently reflect upon them. The recognition of a critical event thus heightens an individuals’ susceptibility to learn and adapt. Following this logic, an individuals’ awareness of discontinuous, critical events might open a window of imprintability (Higgins 2005; Marquis and Tilcsik 2013). As critical incidents usually contain highly emotional content, individuals’ receptivity toward formative experiences is triggered during these periods (Cope and Watts 2000). Thus, individuals might receive stronger imprints if they recognize critical incidents regarding the imprinted content. In a similar vein, Schein (1971) argues that an individual’s receptivity to imprinting forces depends on the level of novelty and uncertainty of a situation or context (Schein 1971). The novelty aspect captures the degree to which an individual is familiar with a context through prior experience and socialization in similar contexts. Uncertainty refers to an individual’s ambiguity toward appropriate behaviors and roles in a given context, for example, when taken-for-granted knowledge and assumptions are challenged or discarded (Pittaway and Cope 2007). Lindh and Thorgren (2016) argue that entrepreneurs recognize critical events because they stimulate strong emotions and feelings, such as fear of failing or feeling inadequate. In discontinuous periods, individuals suffer from anxiety and stress. To reduce uncertainty, people’s susceptibility toward learning from their social environments rises sharply (Schein 1971; Tilcsik 2014). Accordingly, Carr and Sequeira (2007) argue that during periods of discontinuity, children can obtain imprints through their parents’ behaviors and reactions. Gordon and Nicholson (2008) describe how a father and leader of a family firm severed contact with his eldest son due to an act of disapproval; this critical incident arouse intense emotions on the younger brothers, making them susceptible to negative imprints.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the recognition of critical incidents renders individuals particularly receptive toward formative experiences as well as indirect learning mechanisms. Consequently, we propose Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

H3a

Critical incident recognition during childhood increases the effect of personal experiences on social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood.

H3b

Critical incident recognition during childhood increases the effect of parental exposure on social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood.

Figure 1 displays an overview of our hypotheses.

3 Method

3.1 Data collection and sample description

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a quantitative study of social entrepreneurs using a standardized online questionnaire. Many social entrepreneurship studies are based on student samples (e.g. Nga and Shamuganathan 2010; Hockerts 2017) and analyze social entrepreneurial intentions rather than actual activity. Empirical studies on social entrepreneurs and their actual social entrepreneurial activity are scarce. However, earlier research showed that entrepreneurial activity might differ substantially from entrepreneurial intention (Hörisch et al. 2019). In line with this finding, Saebi et al. (2019) call for observable actions as outcome variables (e.g. the launch of a venture) rather than self-reported intentions. Therefore, we collected data from actual social entrepreneurs in Germany. Address data from social ventures was obtained from online databases, such as startsocial.de and Social Impact Lab. Altogether, 667 social entrepreneurs were contacted by phone to request participation. Due to missing data, eight responses needed to be excluded from the dataset, resulting in 148 respondents who completed the online survey (response rate of 22.2 percent). To examine the likelihood of non-response bias, early responses were compared to individuals that responded after the follow-up email as recommended in the literature (Armstrong and Overton 1977). A t-test was used to compare the two groups in terms of the mean responses for the variables parental exposure to social entrepreneurship, personal experience with social entrepreneurship, critical incident recognition and social entrepreneurial activity. The results show no significant differences between early and later responses (Wilk’s lambda = 0.974, p > 0.42); therefore, non-response bias seems to be a minor concern in our study. The descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables are summarized in Table 1.

3.2 Measures

The measurement scales for the variables were adopted from earlier research and modified for the present study’s context of social entrepreneurship. The items in the questionnaire were translated from English to German. To minimize the risks of translation bias, front- and back-translation of the survey instrument were used. An overview of all measured employed is given in the Appendix.

The dependent variable, extent of social entrepreneurial activity, was operationalized based on an item established by Stuart and Abetti (1990) and Forbes (2005) who captured the number of (conventional) ventures started by an individual. We transferred this measure to the context of social entrepreneurship. First, we provided a short explanation of social entrepreneurship by outlining that a social venture puts the creation of a social or ecological value in the center of its business activity. Then we asked respondents to state the total number of social ventures they have founded. We regarded this count measure as more objective as a subjective measure on, for example, the self-reported social impact which is prone to social desirability. Using an objective measure of social impact was not possible due to the different types and areas of the social ventures in our sample ranging from education, migration to health. To compensate for skewness, we used the logarithm of the total number of social ventures founded.

For the independent variables, respondents were asked about parental exposure, personal experience, and critical incidents regarding social entrepreneurship during their childhood. Childhood was defined as the age between four and ten years (Tippelt 2002). Three items were used to measure personal experience with social entrepreneurship, indicating the extent of being involved in social projects during school and leisure time in the individuals’ childhood. Building on previous research (Chrisman et al. 2012; Steinberg et al. 2002) this measure was adapted to the social-entrepreneurship context. The questionnaire also outlined that a social project is an activity with limited time and resources to achieve a social goal and differentiated to social ventures in that a social project is not an economic and legal entity. Testing Cronbach’s alpha (0.774) confirmed the reliability of this measurement approach, as the recommended value of 0.7 was exceeded (Bagozzi and Yi 2012). Parental exposure to social entrepreneurship was modified from Bosma et al. (2012) measure of entrepreneurial role models and consists of three items that measure, on a five-point rating scale, the extent of parents’ engagement in social projects during an individual’s childhood and how much parents were perceived as being role models regarding their social engagement. Again, the Cronbach’s alpha, 0.894, for parental exposure to social entrepreneurship clearly exceeded the critical threshold of 0.7.

The measure critical incident recognition regarding social entrepreneurship was modified from Bjorck and Thurman (2007) using a two-step approach. First, respondents were asked whether they recognized a specific event during their childhood that was important to their later decisions to start the social venture (yes = 1, no = 0). If the answer was “yes”, respondents described the specific event in a few sentences. This verbal answer was evaluated independently by two experts, and non-critical incidents (for example, being raised abroad) were recoded. We used three criteria on determining the existence of a critical incident regarding social entrepreneurship:

-

Is it a central, time-limited, and unique event? (then code as yes = 1)

-

Does the event relate to social issues? (then code as yes = 1)

-

Is it an ongoing activity (for example, permanent commitment), thereby making you unable to name a concrete event? (then code as no = 0)

Testing Krippendorf’s alpha (0.765) confirmed the inter-coder reliability of this procedure. Altogether, 33 individuals (21.2 percent) experienced a critical incident regarding social entrepreneurship in their childhood. As a second step in this two-step approach, respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which the respective event affected their decision to found a social venture, using a five-point scale. The weighted measure of the dummy variable, combined with the strength of influence, was included in the analysis, taking the minimum value zero (for respondents with no critical incidents) and the maximum value five (for respondents who experienced a critical incident that affected them strongly in their future decisions to start social ventures).

As control variables, we included respondents’ age and gender, and whether the individual’s family owns a business (cf. Sørensen 2007; Hechavarría et al. 2017; Suess-Reyes 2017). To reduce the risk of common-method bias, the study uses an objective and quantitative measure, that is, the total number of social ventures founded, for the dependent variable. Furthermore, the variable for critical incidents is based on descriptions and rated by two independent coders. Still, we tested for common-method bias and performed Harman’s single-factor test by entering all items into one exploratory factor analysis. The principal component analysis with varimax rotation showed that the first factor only accounted for 26.3 percent of the total variance. Thus, common-method bias does not seem to be an issue, as no single factor accounted for most of the measures’ covariance. Correlations higher than 0.80, variance-inflation factors (VIFs) above 10 (Kennedy 1992), and condition indices (CIs) over 30 (Grewal et al. 2004) typically indicate serious multicollinearity problems. Analyses show that VIFs are below 1.4, and CIs are below 2.8. These values, combined with the relatively low correlation coefficients (see Table 1), indicate that multicollinearity is unlikely to be a concern in the present study.

4 Results

To test the hypotheses, a moderated regression analysis with bootstrapping was carried out using PROCESS as developed by Preacher and Hayes (2004). The results are displayed in Table 2. In Model 1 only the control variables are included. Model 2 additionally encompasses the main effects of parental exposure to social entrepreneurship during childhood and personal experience with social entrepreneurship during childhood. It indicates that personal experiences with social entrepreneurship during childhood significantly increase future social entrepreneurial activity (b = 0.037, SE = 0.016, p < 0.05, Table 2, Model 2), which supports Hypothesis 1. The more experiences individuals gained in their early lives, the higher their likelihood to engage in social entrepreneurial activity later in life. In contrast, the effect of parental imprints on the extent of future social entrepreneurial activity is not significant, which means that Hypothesis 2 is not supported.

Regarding the proposed interaction effects (Model 3), we find support for a positive interaction effect of personal experience and critical incident recognition on social entrepreneurial activity. Thus, the effect of personal experience during childhood on future social entrepreneurial activity is stronger if individuals experienced critical incidents regarding social entrepreneurship, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3a (b = 0.020, SE = 0.009, p < 0.01, Table 2, Model 3).

Figure 2 depicts the plot of the significant interaction effect of personal experience and critical incident recognition. It illustrates that the interaction effect of personal experience during childhood on future social entrepreneurial activity is significantly stronger with a high level of critical incident recognition (b = 0.070, SE = 0.019, p < 0.01) than with a low level (b = 0.009, SE = 0.021, n.s.). This finding suggests that experiencing one or more critical incidents spurs the positive effect of personal experience on social entrepreneurial activity. Put differently, individuals who gained social entrepreneurship experience and recognized critical incidents during childhood are more likely to engage in social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. In contrast, we do not find empirical support for the interaction effect of parental imprints and critical incident recognition, that is, Hypotheses 3b must be rejected.

Regarding the control variables, age, gender, and family business elicit a significant positive impact on social entrepreneurial activity (Model 1), that is, as expected the number of social ventures founded is higher for older individuals, men, and those from entrepreneurial families.

5 Discussion and conclusions

This study investigates the role of early exposure to social entrepreneurship through personal experiences, as well as parental experiences in explaining the extent of social entrepreneurial activity in adulthood. Based on our theoretical arguments and econometric results, we conclude that individuals’ personal experience with social entrepreneurship during childhood is a strong impetus for the extent of future social entrepreneurial activity. Thus, we support the claim by Marquis and Tilcsik (2013) that research making use of imprinting theory should factor in further sensitive periods, as we found that childhood is a particularly relevant sensitive period for imprinting social entrepreneurial activity, even though it is largely neglected in current entrepreneurship research on imprinting.

5.1 Dissimilarities regarding antecedents of social and conventional entrepreneurs

Research from other theoretical backgrounds found similarities regarding the antecedents of social and conventional entrepreneurship. For example, individual psychological factors, such as compassion or self-efficacy, have been shown to be associated with entrepreneurs’ social goals (Smith and Woodworth 2012; Forster and Grichnik 2013), revealing similarities to findings from conventional entrepreneurial research (e.g. Caliendo et al. 2009; Gruber 2010; Urbig et al. 2012). Likewise, Politis et al. (2016) found that social entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by similar factors as commercial entrepreneurial intentions. Yet, scholars also find support for individual differences between social and conventional entrepreneurs, specifically regarding their entrepreneurial identity (Fauchart and Gruber 2011; Yitshaki and Kropp 2016; Chandra and Shang 2017; Wry and York 2017) and their relevant past experience (Yiu et al. 2014). We add to these insights on similarities and dissimilarities between the antecedents of social and conventional entrepreneurship by showing that personal experience constitutes an important imprinting source for social entrepreneurs. Thus, our results extend earlier insights on imprinting in conventional entrepreneurship (Marquis and Tilcsik 2013; Mathias et al. 2015) to the context of social entrepreneurship.

Extant research on conventional entrepreneurship also observed that the experience and recognition of critical incidents could exert a positive effect on entrepreneurial learning, as well as on entrepreneurial activity (Snell 1992; Cope and Watts 2000; Cope 2005; Pittaway and Cope 2007; Lindh and Thorgren 2016; Mathias et al. 2015). We extended this knowledge to the context of social entrepreneurship and specified that critical incident recognition exert a moderating influence that can leverage the influence of early imprints on social entrepreneurial activity.

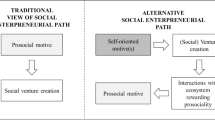

While we found similarities between the antecedents of social and conventional entrepreneurship regarding the influence of personal experience with the respective phenomenon and critical incident recognition, this is not the case for parental influence. Early exposure to social entrepreneurship through parents did not exert a significant influence on the extent of individual’s social entrepreneurial activity. This marks a difference regarding conventional entrepreneurship research, which frequently found that entrepreneurial behavior is passed from one generation to the next (e.g. Sørensen 2007). Interestingly, while exposure to social entrepreneurship through parents was not found to be significant, our results concerning the control variable family business suggest that individuals whose families own a (conventional) business are more likely to show higher levels of social entrepreneurial action. A possible explanation for this finding would be that individuals from entrepreneurial families are less reluctant to become active in entrepreneurship, thereby displaying higher intensities of social entrepreneurial action. Further, being embedded in a family business can promote the entrepreneurial proclivity of children via multiple mechanisms, such as parental role-modeling or entrepreneurial legacy (e.g. Jaskiewicz et al. 2015).

However, there is a difference between exposure to conventional entrepreneurship through family businesses and exposure to parents’ social entrepreneurial behavior. While prior findings suggest that entrepreneurial role modeling precedes future conventional entrepreneurial activity, our findings indicate that social role modeling by parents does not significantly influence future social entrepreneurial activity. We recommend further research to be conducted to investigate in detail the effect of different exposure types on social entrepreneurial behavior.

5.2 Implications for theory and practice

Taken together, the above findings document that imprinting theory is informative in social entrepreneurship research as it can explain social entrepreneurial activity. Research on the antecedents of social entrepreneurial activity mainly builds on the personality-trait approach (Nga and Shamuganathan 2010; Miller et al. 2012; Smith and Woodworth 2012) and intention-based approaches (Forster and Grichnik 2013; Politis et al. 2016; Hockerts 2017). Our paper adds to prior research on the emergence of social entrepreneurs (e.g. Scheiber 2016; Chandra and Shang 2017) by opening a new explanatory approach. Our results show that social entrepreneurship research can be enriched by imprinting theory, and that models explaining the emergence of social entrepreneurial activity can benefit from incorporating elements of imprinting theory. Interestingly, large databases on entrepreneurship, for example, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, which are widely used to explain the emergence of social entrepreneurial activity (e.g., Estrin et al. 2013; Stephan et al. 2015; Hechavarría et al., 2017), do not yet include variables derived from this theoretical approach.

Our research further extends the discussion on imprinting on the individual level by investigating the effect of imprints on the social entrepreneur, as opposed to imprinting effects on an organization (cf. Simsek et al. 2015; Ellis et al. 2017) or on the conventional entrepreneur (cf. Marquis and Tilcsik 2013; Mathias et al. 2015). Most imprinting research on the individual level focuses on imprinting during adolescence and how this affects entrepreneurial activity (Higgins 2005; McEvily et al. 2012). We extend this body of research by connecting imprinting forces during childhood to social entrepreneurial activity, thereby adding theoretical value. Our results illustrate that personal experiences with social entrepreneurship during childhood seem to be more relevant than imprinting effects through third parties, such as parents.

A further theoretical contribution from our study is the integration of critical events into the imprinting process. To date, research has emphasized the role of imprinting in entrepreneurial activity (Lee and Battilana 2013; Mathias et al. 2015), but it did not explain sufficiently how this process is performed and fell short in explaining why some individuals who were subject to imprinting were influenced by the imprint while others were not. As a notable exception, Tilcsik (2014) argues that imprinting strength depends on the extent of learning during socialization, that is, deep and powerful imprints result from strong and extensive learning. He further argues that the stock of prior experience limits individuals’ openness to learning, such that inconsistent formative experiences tend to attenuate imprinting strength. While we agree with the former, our results indicate that the strength of learning does not necessarily depend on the consistency of formative experiences. Our results suggest that of the many formative experiences social entrepreneurs have gained in their lives so far, those that are associated with the recognition of critical events have a long-lasting impact.

Besides these academic insights, our results also can inform entrepreneurship practitioners, as well as policy makers. Based on our results, social entrepreneurs can be sensitized for the influence of childhood experiences on their activity. Similarly, our findings highlight the importance and benefits of critical incident recognition. These insights can be helpful in selecting employees and volunteers for the respective venture. Further, for-profit oriented companies could use these insights to promote socially oriented innovation through social intrapreneurs (Alt and Craig 2016; Niemann et al. 2020). Moreover, many companies have already integrated corporate social responsibility to improve company image, customer loyalty, and stakeholder relations (Schreck 2011; Crane and Glotzer 2016; Alt and Craig 2016). Companies could facilitate imprinting of children to foster social entrepreneurship through direct or indirect participation in social programs at schools. As more and more companies, such as the German producer of utility vehicles, MAN, aim at improving their CSR performance through support of social entrepreneurs, companies could benefit from financing such specifically targeted educational schemes and workshops.

On a societal and political level, the finding on the role of personal experiences with social entrepreneurship calls for making social entrepreneurship more visible and present at an early stage. Prior research on entrepreneurial action in sustainability contexts has documented the importance of media as an antecedent of entrepreneurial activity (Hörisch et al. 2019). For social entrepreneurship, media presence plays a vital role in making this phenomenon more apparent and providing first-contact points. Given our finding that childhood is an important, sensitive period, schools are particularly challenged to provide opportunities for gaining personal experiences with social entrepreneurship. Indeed, in some countries (e.g. Germany and the Netherlands), many schools have introduced mandatory internships in social welfare for students (e.g. Winnubst and de Haan 2015). Additionally, policy makers could support social-entrepreneurship workshops and courses within curricula to increase children’s interest and awareness of such activities. Further research should test the effects of such measures, for example, by evaluating the degree of social entrepreneurial intentions before and after a particular intervention takes place.

5.3 Limitations and future research

Besides evaluating existing schemes that could help increase the visibility of social entrepreneurial action, we recommend that future research collects and analyzes similar data for other countries as it has been shown that social entrepreneurship differs between regions and countries (Kerlin 2006, 2010). As Germany has a social market economy, the conditions of founding a social venture might be different than in, for example, a liberal market economy or a planned economy. Furthermore, risk aversion and fear of failure is stronger in Germany and (social) entrepreneurship education is less established than in other industrialized countries (Lepoutre et al. 2013; Sternberg et al. 2019), so that those cultural differences could also affect the social entrepreneurial activity. Collecting data from different countries, that is extending the geographic and cultural scope of this study, could help overcome a shortcoming of our analysis that is based exclusively on German data and, thus, would help increase the generalizability of our results.

Moreover, we recommend testing whether our results hold in the context of intrapreneurship (Graf and Wirl 2014; Brenk et al., 2019) and corporate environmentalism (Schwens and Wagner 2019), as socially-oriented intrapreneurs might be influenced by different imprinting mechanisms than social entrepreneurs. On a similar note, while our study did not find that parental exposure to social entrepreneurship enhances future social entrepreneurial activity, results indicate that individuals from conventional family firms are more likely to become a social entrepreneur. As Suess-Reyes (2017) has shown that business family identity is positively related to the orientation of the business, future research is encouraged to expand into this subject and investigate how business family identity affects the spawning of social entrepreneurs.

Another limitation of our paper is the retrospective character of the information used, as we gathered data from individuals who already had founded at least one social venture. We used the critical-incident technique to ask social entrepreneurs to recall cognitively salient social experiences. The same sense-making process that produces hindsight bias has been shown to benefit us by reducing the sting of negative emotional events (Wilson et al. 2003) and may help us to learn from the outcome, even if we do not realize it (Pezzo and Pezzo 2007). Hoch and Loewenstein (1989) argued that the presence of hindsight bias is a sign that learning is taking place. Although research showed that retrospective bias is rather small in effect size (Pezzo 2011) and each event was coded independently by two experts, we cannot rule out the possibility of retrospective bias (Dacin et al. 2010), which might have informed the respondents’ evaluation of their past experiences. We recommend that future studies collect and analyze longitudinal data to overcome this limitation.

Moreover, future research could extend the focus of our work. Our paper analyzes the influence of different sources of imprinting on social entrepreneurial activity. Further analyses could test whether such imprint sources not only influence activities, but also the outcomes of such activities. In this context, comparing the actual operations of social and conventional entrepreneurial ventures is of crucial importance. For example, it might be the case that entrepreneurs with greater exposure to social entrepreneurship during their childhood, and who experienced critical incidents, are more effective at or focused on delivering high levels of outcomes in their social entrepreneurial activities (e.g. measured as the share of people in need who benefit from the venture or the growth rate of the respective venture; cf. Whitman 2011).

Furthermore, our study focused on the early imprints during childhood. Early adulthood is the time in which individuals are required to finally make their career choices and in which prior career options and career plans are evaluated more extensively and either confirmed or rejected. Transferring our research to later formative stages such as apprenticeship trainings (e.g. Rupietta and Backes-Gellner 2019) might be an interesting avenue for future research.

Finally, further research into the cognitive processes behind the formative mechanisms seems promising. Our results suggest that the recognition of critical incidents can initiate cognitive processes and thus influence when imprinting occurs. Lindh and Thorgren (2016, p. 525) emphasize that “extant theory has described reflection and learning as processes of interaction among an individual’s various experiences and has emphasized that critical events are important for these processes”, but there is a need to learn how these processes relate to imprinting. Together with the analysis at hand, future research that makes use of imprinting theory in social entrepreneurship could help to foster the potential of social entrepreneurship to tackle social challenges. Our results suggest that to unleash the social entrepreneurial potential of individuals, different sources of imprinting are needed for imprinting conventional entrepreneurial activity.

References

Aldrich HE, Kim PH (2007) Small worlds, infinite possibilities? How social networks affect entrepreneurial team formation and search. Strateg Entrepreneurship J 1:147–165

Alt E, Craig JB (2016) Selling issues with solutions: igniting social intrapreneurship in for-profit organizations. J Manage Stud 53(5):794–820

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res 14(3):396–402

Azoulay PC, Liu C, Stuart TE (2017) Social influence given (partially) deliberate matching: career imprints in the creation of academic entrepreneurs. Am J Sociol 122:1223–1271

Bacq S, Hartog C, Hoogendoorn B (2016) Beyond the moral portrayal of social entrepreneurs: empirical approach to who they are and that drives them. J Bus Ethics 133(4):703–718

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (2012) Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 40:8–34

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs

Battilana J, Sengul M, Pache A-C, Model J (2015) Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: the case of work integration social enterprises. Acad Manag J 58:1658–1685

Bercovitz J, Feldman M (2008) Academic entrepreneurs: organizational change at the individual level. Organ Sci 19:9–30

Bjorck JP, Thurman JW (2007) Negative life events, patterns of positive and negative religious coping, and psychological functioning. J Sci Study Relig 46:159–167

Bornstein D, Davis S (2010) Social entrepreneurship: What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bosma N, Hessels J, Schutjens V, van Praag M, Verheul I (2012) Entrepreneurship and role models. J Econ Psychol 33:410–424

Brenk S, Lüttgens D, Diener K, Piller F (2019) Learning from failures in business model innovation: solving decision-making logic conflicts through intrapreneurial effectuation. J Bus Econ 89:1097–1147

Breugst N, Patzelt H, Rathgeber P (2015) How should we divide the pie? Equity distribution and its impact on entrepreneurial teams. J Bus Ventur 30(1):66–94

Bruhn AR (1985) Very early memories as a projective technique: the cognitive-perceptual method. J Pers Assess 49:587–597

Bruner J (2003) Self-Making Narratives. In: Fivush R, Haden CA (eds) Autobiographical memory and the construction of a narrative self. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, pp 209–225

Byrne M, Willis P, Burke J (2012) Influences on school leavers’ career decisions—implications for the accounting profession. Int J Manag Educ 10:101–111

Caliendo M, Fossen FM, Kritikos AS (2009) Risk attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs—new evidence from an experimentally validated survey. Small Bus Econ 32:153–167

Carr JC, Sequeira JM (2007) Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent. A theory of planned behavior approach. J Bus Res 60:1090–1098

Carroll GR, Mosakowski E (1987) The career dynamics of self-employment. Adm Sci Q 32(4):570–589

Chandra Y, Shang L (2017) Unpacking the biographical antecedents of the emergence of social enterprises. A narrative perspective. VOLUNTAS: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 28:2498–2529

Chrisman JJ, McMullan WE, Kirk JR, Holt DT (2012) Counseling assistance, entrepreneurship education, and new venture performance. J Entrepreneurship Public Policy 1:63–83

Cope J (2005) Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory Practice 29:373–397

Cope J, Watts G (2000) Learning by doing – An exploration of experience, critical incidents and reflection in entrepreneurial learning. Int J Entrep Behav Res 6:104–124

Corner PD, Ho M (2010) How opportunities develop in social entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Practice 34:635–659

Crane A, Glotzer S (2016) Researching corporate social responsibility communication: themes, opportunities and challenges. J Manage Stud 53(7):1223–1252

Dacin PA, Dacin MT, Matear M (2010) Social entrepreneurship: Why we don't need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Acad Manag Perspect 24:37–57

Dacin MT, Dacin PA, Tracey P (2011) Social entrepreneurship: a critique and future directions. Organ Sci 22:1203–1213

Defourny J, Nyssens M (2008) Social enterprise in Europe: recent trends and developments. Soc Enterp J 4(3):202–228

Dokko G, Wilk SL, Rothbard NP (2009) Unpacking prior experience: How career history affects job performance. Organ Sci 20:51–68

Eesley C, Wang Y (2017) Social influence in career choice. Evidence from a randomized field experiment on entrepreneurial mentorship. Res Policy 46:636–650

Ellis S, Mendel R, Nir M (2006) Learning from successful and failed experience. The moderating role of kind of after-event review. J Appl Psychol 91:669–680

Ellis S, Aharonson BS, Drori I, Shapira Z (2017) Imprinting through inheritance: a multi-genealogical study of entrepreneurial proclivity. Acad Manag J 60:500–522

Estrin S, Mickiewicz T, Stephan U (2013) Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions. Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrep Theory Pract 37:479–504

Fauchart E, Gruber M (2011) Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries: the role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Acad Manag J 54:935–957

Forbes DP (2005) Are some entrepreneurs more overconfident than others? J Bus Ventur 20:623–640

Forster F, Grichnik D (2013) Social entrepreneurial intention formation of corporate volunteers. J Soc Entrep 4:153–181

Furlong A, Biggart A (1999) Framing ‘choices’: a longitudinal study of occupational aspirations among 13-to 16-year-olds. J Educ Work 12:21–35

Gordon G, Nicholson N (2008) Family wars. Classic conflicts in family business and how to deal with them. Kogan Page, London

Graf D, Wirl F (2014) Corporate social responsibility: a strategic and profitable response to entry? J Bus Econ 84(7):917–927

Grewal R, Cote JA, Baumgartner H (2004) Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models. Implic Theory Test Mark Sci 23:519–529

Gruber M (2010) Exploring the origins of organizational paths. Empirical evidence from newly founded firms. J Manag 36:1143–1167

Hechavarría DM, Terjesen SA, Ingram AE, Renko M, Justo R, Elam A (2017) Taking care of business. The impact of culture and gender on entrepreneurs’ blended value creation goals. Small Bus Econ 48:225–257

Higgins MC (2005) Career imprints: creating leaders across an industry. Jossey Bass, San Francisco

Hoch SJ, Loewenstein GF (1989) Outcome feedback: Hindsight and information. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 15(4):605–619

Hockerts K (2017) Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep Theory Pract 41:105–130

Hoogendoorn B (2016) The prevalence and determinants of social entrepreneurship at the macro level. J Small Bus Manage 54:278–296

Hörisch J, Kollat J, Brieger SA (2019) Environmental orientation among nascent and established entrepreneurs: an empirical analysis of differences and their causes. Int J Entrep Vent 11:373–393

Jaskiewicz P, Combs JG, Rau SB (2015) Entrepreneurial legacy. Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 30:29–49

Kennedy P (1992) A guide to econometrics. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Kerlin JA (2006) Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: understanding and learning from the differences. VOLUNTAS: Int J Volunt Nonprofit. Organ 17:246

Kerlin JA (2010) A comparative analysis of the global emergence of social enterprise. VOLUNTAS: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 21:162–179

Kosse F, Deckers T, Pinger P, Schildberg-Hörisch H, Falk A (2020) The formation of prosociality: causal evidence on the role of social environment. J Polit Econ 128(2):434–467

Kraus S, Filser M, O’Dwyer M, Shaw E (2014) Social entrepreneurship: an exploratory citation analysis. RMS 8:275–292

Kuhn T, Weibler J (2011) Ist Ethik ein Erfolgsfaktor? Unternehmensethik im Spannungsfeld von Oxymoron Case, Business Case und Integrity Case. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft 81(1):93–118

Laspita S, Breugst N, Heblich S, Patzelt H (2012) Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. J Bus Ventur 27:414–435

Lee M, Battilana J (2013) How the zebra got its stripes: imprinting of individuals and hybrid social ventures. Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 14–005. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/pages/item.aspx?num=45088

Lepoutre J, Justo R, Terjesen S, Bosma N (2013) Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity. The global entrepreneurship monitor social entrepreneurship study. Small Bus Econ 40:693–714

Lindh I, Thorgren S (2016) Critical event recognition. An extended view of reflective learning. Manag Learn 47:525–542

Lumpkin GT, Bacq S, Pidduck RJ (2018) Where change happens: community-level phenomena in social entrepreneurship research. J Small Bus Manage 56(1):24–50

Mair J, Martí I (2006) Social entrepreneurship research: a source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J World Bus 41:36–44

Marquis C, Tilcsik A (2013) Imprinting. Toward a multilevel theory. Acad Manag Ann 7:195–245

Martin BC, McNally JJ, Kay MJ (2013) Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: a meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. J Bus Ventur 28:211–224

Marzana D, Vecina ML, Marta E, Chacón F (2015) Memory of the quality of group experiences during childhood and adolescence in predicting volunteerism in young adults. VOLUNTAS: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 26:2044–2060

Mathias BD, Williams DW, Smith AR (2015) Entrepreneurial inception. The role of imprinting in entrepreneurial action. J Bus Ventur 30:11–28

McEvily B, Jaffee J, Tortoriello M (2012) Not all bridging ties are equal: network imprinting and firm growth in the Nashville legal industry, 1933–1978. Organ Sci 23:547–563

McGrath RG, MacMillan IC (2000) The entrepreneurial mindset. Strategies for continuously creating opportunity in an age of uncertainty. Harvard Business Press, Boston

Miller TL, Grimes MG, McMullen JS, Vogus TJ (2012) Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Acad Manag Rev 37:616–640

Minniti M, Bygrave W (2001) A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship 25(3):5–16

Narang Y, Narang A, Nigam S (2014) Scaling the impact of social entrepreneurship from production and operations management perspective-a study of eight organizations in the health and education sector in India. Int J Bus Glob 13:455–481

Nga JKH, Shamuganathan G (2010) The influence of personality traits and demographic factors on social entrepreneurship start up intentions. J Bus Ethics 95:259–282

Niemann C, Dickel P, Eckardt G (2020) The interplay of corporate entrepreneurship, environmental orientation and performance in clean-tech firms – a doubled-edged sword. Bus Strateg Environ 29:180–196

Pancer SM, Pratt M (1999) Social and family determinants of community and political involvement in Canadian youth. In: Yates M, Youniss J (eds) Community service and civic engagement in youth: International perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 32–35

Parkinson C, Howorth C (2008) The language of social entrepreneurs. Entrep Reg Dev 20:285–309

Pezzo MV (2011) Hindsight bias: a primer for motivational researchers. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 5(9):665–678

Pezzo MV, Pezzo SP (2007) Making sense of failure: a motivated model of hindsight bias. Soc Cogn 25(1):147–164

Phillips W, Lee H, Ghobadian A, O’Regan N, James P (2014) Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: a systematic review. Group Organ Manag 40:428–461

Pillemer DB (1998) What is remembered about early childhood events? Clin Psychol Rev 18:895–913

Pittaway L, Cope J (2007) Simulating entrepreneurial learning: Integrating experiential and collaborative approaches to learning. Manag Learn 38:211–233

Politis D (2005) The process of entrepreneurial learning: a conceptual framework. Entrep Theory Pract 29:399–424

Politis K, Ketikidis P, Diamantidis AD, Lazuras L (2016) An investigation of social entrepreneurial intentions formation among south-east European postgraduate students. J Small Bus Enterp Develop 23:1120–1141

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2004) SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 36:717–731

Prieto LC, Phipps STA, Friedrich TL (2012) Social entrepreneur development: an integration of critical pedagogy, the theory of planned behavior and the Acs model. Acad Entrep J 18:1–16

Rahdari A, Sepasi S, Moradi M (2016) Achieving sustainability through Schumpeterian social entrepreneurship: the role of social enterprises. J Clean Prod 137:347–360

Rupietta C, Backes-Gellner U (2019) How firms’ participation in apprenticeship training fosters knowledge diffusion and innovation. J Bus Econ 89(5):569–597

Saebi T, Foss NJ, Linder S (2019) Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. J Manag 45(1):70–95

Salzmann AJ (2013) The integration of sustainability into the theory and practice of finance: an overview of the state of the art and outline of future developments. J Bus Econ 83(6):555–576

Sastre-Castillo MA, Peris-Ortiz M, Valle D-D (2015) What is different about the profile of the social entrepreneur? Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 25:349–369

Scheiber L (2016) How social entrepreneurs in the third sector learn from life experiences VOLUNTAS. Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 27:1694–1717

Schein EH (1971) The individual, the organization, and the career: a conceptual scheme. J Appl Behav Sci 7:401–426

Schreck P (2011) Ökonomische Corporate Social Responsibility Forschung – Konzeptionalisierung und kritische Analyse ihrer Bedeutung für die Unternehmensethik. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft/J Bus Econ 81:745–769

Schwens C, Wagner M (2019) The role of firm-internal corporate environmental standards for organizational performance. J Bus Econ 89(7):823–843

Shumate M, Atouba Y, Cooper KR, Pilny A (2014) Two paths diverged. Manag Commun Q 28:404–421

Simsek Z, Fox BC, Heavey C (2015) “What’s past is prologue” A framework, review, and future directions for organizational research on imprinting. J Manag 41:288–317

Siqueira ACO, Guenster N, Vanacker T, Crucke S (2018) A longitudinal comparison of capital structure between young for-profit social and commercial enterprises. J Bus Ventur 33:225–240

Smith IH, Woodworth WP (2012) Developing social entrepreneurs and social innovators. A social identity and self-efficacy approach. Acad Manag Learn Educ 11:390–407

Snell R (1992) Experiential learning at work. Why can’t it be painless? Pers Rev 21:12–26

Sørensen JB (2007) Closure and exposure: Mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of self-employment. In: Ruef M, Lounsbury M (eds) The sociology of entrepreneurship. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 83–124

Steinberg KS, Rooney PM, Chin W (2002) Measurement of volunteering: a methodological study using Indiana as a test case. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 31:484–501

Stephan U, Uhlaner LM, Stride C (2015) Institutions and social entrepreneurship. The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. J Int Bus Stud 46:308–331

Sternberg R, Wallisch M, Gorynia-Pfeffer N, von Bloh J, Baharian A (2019) Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: Unternehmensgründungen im weltweiten Vergleich—Länderbericht Deutschland 2018/19. Online https://www.gemconsortium.org/report

Stuart RW, Abetti PA (1990) Impact of entrepreneurial and management experience on early performance. J Bus Ventur 5:151–162

Suess-Reyes J (2017) Understanding the transgenerational orientation of family businesses: the role of family governance and business family identity. J Bus Econ 87:749–777

Tilcsik A (2014) Imprint–environment fit and performance. Adm Sci Q 59:639–668

Tippelt R (2002) Handbuch Bildungsforschung. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden

Tracey P, Phillips N (2007) The distinctive challenge of educating social entrepreneurs: a postscript and rejoinder to the special issue on entrepreneurship education. Acad Manag Learn Educ 6:264–271

Urbig D, Weitzel U, Rosenkranz S, van Witteloostuijn A (2012) Exploiting opportunities at all cost? Entrepreneurial intent and externalities. J Econ Psychol 33:379–393

Whitman J (2011) Social entrepreneurship: An overview. In: Entrepreneurship J (ed) Bygrave W, Zacharakis A. Wiley, New York, pp 563–582

Wilson TD, Gilbert DT, Centerbar DB (2003) Making sense: the causes of emotional evanescence. Psychol Econ Decis 1:209–233

Winnubst P-M, de Haan L (2015) Internships in the Netherlands. Fond dalšího vzdělávání, Prague

Wry T, York JG (2017) An identity-based approach to social enterprise. Acad Manag Rev 42:437–460

Yitshaki R, Kropp F (2016) Entrepreneurial passions and identities in different contexts: a comparison between high-tech and social entrepreneurs. Entrep Reg Dev 28:206–233

Yiu DW, Wan WP, Ng FW, Chen X, Su J (2014) Sentimental drivers of social entrepreneurship: a study of China’s Guangcai (Glorious) Program. Manag Organ Rev 10:55–80

Zahra SA, Gedajlovic E, Neubaum DO, Shulman JM (2009) A typology of social entrepreneurs: motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J Bus Ventur 24(5):519–532

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A1. Measurement scales of main variables

Social entrepreneurial activity |

1. Please state the number of social ventures that you have founded |

The logarithm of this number was used to compensate for skewness |

Personal experiences with social entrepreneurship in childhood |

Please state to what extent you have gained the following social entrepreneurial experiences during your childhood (1 = never, 5 = very often) |

1. I had at least one school subject related to social entrepreneurship |

2. I have participated in social school projects |

3. I was socially engaged in my free time |

The average score of these items was used as the overall measure |

Parental exposure to social entrepreneurship |

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) |

1. My parents were a role model for me in terms of their social engagement during my childhood |

2. My parents’ social engagement during my childhood was the main reason why I later got engaged with social issues myself |

3. Without my parents as a socially engaged role model during my childhood, I would not have taken any first steps towards starting my own social venture |

The average score of these items was used as the overall measure |

Critical incident recognition regarding social entrepreneurship in childhood |

1. Please briefly describe an event from your childhood that you consider most important for your social venture |

Not stating a specific event (“I have not experienced a specific event”) was coded as 0. If the respondents described a specific event, the verbal answer was evaluated independently by two experts, and non-critical incidents (for example, being raised abroad) were recoded. We used three criteria on determining the existence of a critical incident regarding social entrepreneurship |

• Is it a central, time-limited, and unique event? (then code as yes = 1) |

• Does the event relate to social issues? (then code as yes = 1) |

• Is it an ongoing activity (for example, permanent commitment), thereby making you unable to name a concrete event? (then code as no = 0) |

2. What influence did the event have on your perception of a social problem related to your social venture? (1 = no influence, 5 = very strong influence) |

The weighted measure of the dummy variable (1), combined with the strength of influence (2) was used as the overall measure |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dickel, P., Sienknecht, M. & Hörisch, J. The early bird catches the worm: an empirical analysis of imprinting in social entrepreneurship. J Bus Econ 91, 127–150 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-020-00969-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-020-00969-z