Abstract

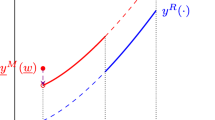

Under the German Inheritance Tax and Gift Tax Act, the transfer of business assets can be exempted from taxation up to 100%. However, this exemption depends on the evolution of the company’s payroll, which is highly uncertain. We model the uncertain nature of payroll evolution using a Geometric Brownian motion. We obtain closed-form solutions for the expected effective exemption and for the expected effective tax rate. We find that the uncertainty effect is most pronounced for moderate negative and positive growth rates. Furthermore, higher uncertainty reduces the value of the effective tax exemption. Also, we find that the (partially progressive) German inheritance tax function by trend promotes standard exemption. The results enable tax planners to make an optimal choice between standard or full exemption and allow for calculating the expected tax burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While the German Constitutional Court invalidated key provisions of the German Inheritance and Gift Tax Act in its 17 Dec 2014 ruling on the grounds that they violated the principle of equality (Section 3 (1) of the Basic Law/Grundgesetz), it also stated that the very privilege of business property is not unconstitutional in light of the higher aim of not endangering the going concern of companies. The Inheritance Tax Reform Act of 2016, which came into force on 1 July 2016, amended the Inheritance Tax and Gift Tax Act in line with the Court’s requirements. For example, the payroll sum criterion now applies for companies with more than five employees (previously: more than 20 employees).

Note that we only describe the regulations of the German Inheritance Tax Law in a stylized way since we are interested in the economic effects of the payroll criterion. These effects are independent of the prerequisites necessary for obtaining preferential treatment in the first place.

We restrict our analysis to companies with more than 15 employees. Our model could be easily adopted to cover lower numbers of employees. However, in Sect. 3.2, we assume that compensation expenses are normally distributed. This assumption may be violated in companies with a relatively low number of employees.

The possibility of endogeneity of the payroll evolution is discussed in Sect. 4.3.

See Section 200 of the German Valuation Law (BewG, Bewertungsgesetz).

The heir is also allowed to use a different valuation method (Section 11 (2) BewG). However, the simplified valuation method is often more attractive because of two reasons: (1) using a different valuation method involves high costs for an expertise; (2) using the fixed multiplicator of 13.75 corresponds to discounting with a rate of 7.3%, which is beneficial compared to the currently low base rate.

Thus, we ignore the fact that the payroll expense base is calculated as an average of the preceding 5 years according to the German Inheritance and Gift Tax Act. This simplification is relaxed in Sect. 4.2.

Note that the time periods may actually be shorter than 5 or 7 years because of the time lag between the tax triggering event and the point in time at which the inheritance tax assessment becomes materially definitive. We address this issue in Sect. 4.2.

Effective tax rates as we use them here should not be confused with the eponymous concepts in the field of income taxes based on investment-neutral tax concepts as a yardstick. Therefore, an effective (inheritance) tax rate which equals the nominal tax rate does not necessarily mean that the inheritance tax is investment-neutral (in whatever context); it only means that there are no timing-effects or tax-base effects at work.

Note that in any practical application the critical value for \(\alpha\) has to be calculated in discrete time. Thus, it is given by the solution to \(0.85 \cdot \text {Min}\left\{ \frac{ \frac{1}{5}\sum _{t=1}^5 (1+\alpha )^t }{0.8} ,1 \right\} = \text {Min}\left\{ \frac{1}{7}\sum _{t=1}^7(1+\alpha )^t ,1 \right\}\Longleftrightarrow \alpha = -\,0.0406\).

The effective exemption \(d_{eff }\) depends on the growth rate \(\alpha\). Formally, we write \(d_{eff }(\alpha )\). Solving \(d_{eff }(\alpha )=d\Longleftrightarrow c=1 \Longleftarrow \int _0^T e^{\alpha t}\,dt= T k\) for \(\alpha\) (given \(T=5,k=0.8\)), one obtains \(\alpha = -\,0.0928\).

The effective exemption depends (among other things) on the growth and interest rates. For this purpose, we write \(d_{eff }(\alpha ,i_s)\). The heir is indifferent between full and standard exemption iff \(d_{eff }^{\text {full}}(\alpha ,i_s)=d_{eff }^{\text {std}}(\alpha ,i_s)\). Solving for \(i_s\) one obtains the interest rate (as a function of \(\alpha\)) that renders the heir indifferent between full and standard exemption. Let \(i_s^{\text {ind}}(\alpha )\) denote this solution. The highest possible interest rate which renders the heir indifferent is given by \(\max i_s^{\text {ind}}(\alpha )= 0.0811\), where \(\arg \max i_s^{\text {ind}}(\alpha ) = -\,0.0928\). Note that, using annual growth rates and discounting, one obtains \(\arg \max i_s^{\text {ind}}(\alpha ) = -\,0.0735\) and \(\max i_s^\text {ind}(\alpha ) = 0.0784\).

This approach is elaborated and can be found in, e.g., von Weizsäcker (1993).

We tested this approach with a sample of German companies for which more than ten values (since 1990) could be found in the Thomson One Banker database (\(N=212\)). We examined graphically the pooled standardized changes in compensation expenses. The H0 of non-normality is rejected.

The numbers only apply to the example presented in the text, i.e., \(i_s=0.05\) and \(\sigma =0.1\).

Refer to Sect. 4.4.2 for the case of progressive taxation.

See Sect. 2 for legal basics.

Recall that Franke et al. simulate future payroll expenses (and, thus, future ratios \(\zeta\)) using Markov chains. Here, 1% of the runs lead to an outcome where a company has incentives to manipulate the payroll expenses.

We employ the notation used throughout this paper, for the sake of clarity.

Note that the approximation is not valid if \(\alpha =0\) and \(\sigma =0\) since \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\) are not defined in this case. When taking the limit, one obtains \(\lim _{\sigma \rightarrow 0 } \lim _{\alpha \rightarrow 0}\lambda _1 =0\) and \(\lim _{\sigma \rightarrow 0 } \lim _{\alpha \rightarrow 0}\lambda _2 =0\). Eventually, zero variance is not a valid parameter for the lognormal distribution. While the results under uncertainty approach the results under certainty for \(\sigma \rightarrow 0\), we find that numerical instability occurs for \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\) and (very) small \(\sigma\).

Please refer to footnote 24 for an explanation on the interaction between interest rate and progression effect.

\(x_1\) is not relevant for the effects discussed here. Making the function dependent on the upper boundary of its domain is just a convenient way of ensuring that the tax payment does not exceed the tax base. We set \(x_1=10{,}000{,}000\) throughout the discussion.

Note that in this section we set the interest rate to zero. As discussed above, increasing positive interest rates promote full exemption because, when discounting, possible back taxes are worth less from today’s viewpoint. Hence, the timing effect and the tax progression effect are opposite—a well-known result from other areas of business taxation.

In practice, tax functions often feature more “steps” or combined direct and indirect progression.

Recall that we ignore general tax-free allowances which may be granted depending on the degree of kinship according to Section 16 ErbStG (see also footnote 32). Also, we ignore the rounding rule of Section 10 (1) ErbStG.

The function is printed in the “Appendix”.

This remark is only for explanatory purposes. As explained above, we restrict our model to companies with more than 15 employees. Here, a transferred amount of 75,000 is unrealistically low.

Overall, the results do not change qualitatively when applying full exemption instead. Some results are valid only for standard exemption, however; these results are indicated and discussed in the main text.

Note that the approximation made in Sect. 3.2.1 may not be exact for extreme scenarios with a very high standard deviation. Therefore, the results for high standard deviations should be seen as a theoretical benchmark. Keep in mind that \(\sigma =0.5\) already implies a standard deviation of 5 M if the payroll sum base is 10 M. Also note the different scaling of the abscissa in the section on the payment effect (\(\sigma \in [0,3]\)) compared to the section on the decision related effect (\(\sigma \in [0,0.6]\)). We choose the different scalings since the switch of optimality occurs at a relatively low standard deviation whereas in this subsection, we want to show that the payment progression effect vanishes for a high standard deviation.

Also, note that this result is only valid under standard exemption. Under full exemption, there is always a payment progression effect. See also the explanation on the payment progression effect on example 2.

Incorporating general tax allowances as granted by Section 16 ErbStG would increase the (negative) progression effect for relatively low values of V (see example 2). If the heir is a child of the legator, for example, this (additional) payment progression effect vanishes if the transferred amount exceeds \(400{,}000/(1-0.85)=2{,}666{,}667\).

References

Atkinson AB, Stiglitz JE (1980) Lectures on public economics. Mc Graw-Hill, New York

Diller M, Löffler A (2012) Inheritance tax and valuation. World Tax J 4(3):249–258

Fenton LF (1960) The sum of log-normal probability distributions in scatter transmission systems. IRE Trans Commun Syst 8(1):57–67

Franke B, Simons D, Voeller D (2016) Who benefits from the preferential treatment of business property under the german inheritance tax? J Bus Econ 86:997–1041

Franke SF (1983) Theorie und Praxis der indirekten Progression. Nomos, Baden-Baden

Hull JC (2009) Options, futures and other derivatives, 7th edn. Pearson Education, New Jersy

Jakobsson U (1974) On the measurement of the degree of progression. J Public Econ 5:161–168

Mitchell RL (1968) Permanence of the log-normal distribution. J Opt Soc Am 58(9):1267–1272

Musgrave RA, Thin T (1948) Income tax progression. J Polit Econ 56(6):498–514

Scholten G, Korezkij L (2009) Nachversteuerung nach §§ 13a und 19a erbstg als risiko- und entscheidungsfaktor. DStR 47:991–1002

Simons D, Voeller D, Corsten M (2012) Erbschaftsteuerliche Verschonungsregeln für das Betriebsvermögen—ein theoretischer ansatz zur Steuerplanung. Schmalenbachs Z Forsch 64:2–36

Turnbull SM, Wakeman LM (1991) A quick algorithm for pricing european average options. J Financ Quant Anal 26(3):377–389

von Weizsäcker R (1993) A theory of earnings distribution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two anonymous referees for insightful comments that have significantly improved this paper. Also, we want to thank Hans-Georg Schwarz for helpful comments and for translating an earlier version of this paper into English. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The tariff according to Section 19 ErbStG (“tax bracket I”) is given by

“Tax bracket I” applies for (1) spouses and life partners; (2) children, stepchildren and their children, stepchildren; (3) parents and grandparents. Tax brackets II and III feature higher tax rates and apply for more remote degrees of kinship (c.f. Section 15 ErbStG).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diller, M., Späth, T. & Lorenz, J. Inheritance tax planning with uncertain future payroll expenses: an analytical solution to the optimal choice between full and standard exemption. J Bus Econ 89, 599–626 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-019-00929-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-019-00929-2