Abstract

In recent years, universities increasingly had to compete for talented students. Besides running other marketing activities, universities began to cooperate with local professional soccer clubs. However, there is missing evidence on the positive effects of such collaborations. One possible benefit of having a local professional soccer team in a city could be the attraction of new students. Although soccer is an important leisure activity, research insights into the relationship between professional soccer and the demand for studies are rare. In this context, we consider promotions and relegations of professional soccer clubs and their impact on student enrollment growth, since these events are exogenous and time variant leading to an exogenous change of local public goods, private goods and media attention. Focusing on public German universities, dynamic panel regressions show that promotions and relegations of the best local soccer club to the next higher or lower division significantly influence the number of student enrollments in the upcoming semester. This effect is mainly driven by exceptional promotions and relegations. Moreover, student growth is affected by other external shocks on the education system such as double graduation or the status of being an “elite university”. Surprisingly, research funds and tuition fees were found to have no effect. The results provide considerable insights for decision makers, signifying that the sporting performance of professional local soccer clubs might affect enrolment decisions and could be used as an indicator for predicting the expected number of upcoming student applications or serve as an additional instrument in marketing campaigns and recruiting activities of a university.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Among various factors, there are four key determinants of the recent increasingly tough competition between higher education institutions: (1) decreasing cultural and legal barriers (transportation, languages, Bologna policy), (2) rising comparability of higher education institutions based on available quality rankings labels and accreditation procedures, (3) higher performance-orientated allocation of financial resources within the educational system, and (4) an increasing demand for graduates (Weimar et al. 2013).

For instance, the University of Bremen states at their webpage: “10 reasons to study in Bremen […] Werder Bremen: a must during your stay in Bremen. Come and see one of Germany’s—if not one of Europe’s—best soccer teams—together with another 40,000 enthusiastic supporters. An unforgettable experience” (http://www.uni-bremen.de).

In this regard, predefined answers limit the number of response options, whereby important information’s on the motives of students’ university choice could be missing (Obermeit 2012; Lamnek 2005).

The focus on soccer is justified by its nationwide relevance, the media coverage of individual sport teams and by the status of being by far the most popular sport in Germany. Referring to the membership numbers in 2015 (DOSB 2016), Soccer has 6.8 million members in Germany. Other team sports like handball, volleyball or basketball, might generate positive externalities, however, the extent of possible positive externalities tend to be small because the fan community is comparatively limited (Membership numbers in 2015: handball 0.8 million, table tennis 0.6 million, volleyball 0.4 million, basketball 0.2 million). Additionally, contrary to other leisure activities, soccer is a time-variant leisure good, since clubs can be relegated or promoted, which can be seen as an exogenous shock to the utility obtained from a sport club.

Educational factors include the quality of academic teaching (e.g. the range of offered courses and content of teaching), care situation and student-professor ratio, the standard period of study, and alignment of the tertiary education in accordance with student employability [for Australia see Soutar and Turner (2002). For Germany see Fischer and Kampkötter (2016), Hachmeister et al. (2007), Horstschräer (2012). For UK see Abbott and Leslie (2004), Lenton (2015).

In line with the excellence competition run by the German government, eligible universities were awarded with up to three funding lines: “future concepts”, “cluster of excellence” and “graduate school”. We named universities that received at least one of the three funding lines as “university of excellence”. Universities that received funding for “future concepts” are usually labeled as “elite Universities”.

In contrast to the average ticket price (cheapest seat price) for first division soccer (25€), second division soccer (20€) and third division soccer (18€), alternative leisure activities such as Musicals (50€), concerts (40€), theater (18€), day pass aqua park (20€), day pass ski resorts (20–50€) and cinema (8–15€) seem to be associated with similar costs per visit.

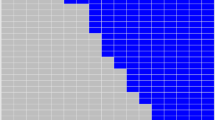

The total number of 77 public universities has been reduced by excluding two universities of the German armed forces (Hamburg and Munich), since an enrollment strictly depends on the entrance to the German armed forces. Hence, the demand for studying resources is not comparable to the demand for public universities.

Enrollments in Germany mostly occur in the winter term and studies in Germany are usually organized as semesters.

Growth rates could bias models toward smaller universities, whereas the use of absolute numbers could bias measurements toward larger universities (Cooper et al. 1994).

We estimated an Im-Pesaran-Shin test and a Fisher augmented Dickey Fuller test. Both tests revealed insignificant test statistics for the absolute values (proving non-stationarity) and significant test statistics for the growth rates (proving stationarity).

Data source: http://www.fussballdaten.de.

If there were multiple professional clubs in a city, we focused on the most successful club. Different clubs are certainly poor substitutes; nevertheless, in no case did we observe the second best team becoming the best team over the period of observation. Hence, we assume no bias effects by changing teams of observation.

During the time of observation, the German football system was restructured twice, whereby the names of the leagues and the number of teams per league changed. However, the league levels remained unchanged.

Data source: http://www.genesis.destatis.de.

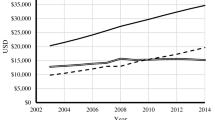

In Germany, public universities are mostly financed by basic public funds. However, institutions can request additional public and private research funds to finance additional academic employees.

The data is not publicly available and was kindly provided by the German Federal Statistical Office (DESTATIS). The growth rate of external research funds give no information about the absolute performance of the university. Despite negative relative changes, the performance of an institution in gathering external research funds might still be outstanding.

In Germany, tuition fees are exogenous for higher education institutions, since the decision of charging tuition fees can only be made by the state government. Therefore, higher education institutions cannot charge individual tuition fees. If the state government decides to charge study fees, then all universities in the state are obligated to charge the same amount of tuition fees.

Only Hamburg reduced the tuition fees from €500 to €375 between 2008 and 2012. However, despite that difference, we assume that this difference is only of marginal importance as the negative “signal” of charging fees remained. Consequently, we also treated the period in Hamburg in an equal way to all other periods of tuition fees by using dichotomous information.

In 2006, Duisburg and Essen merged. Numbers in the previous years were aggregated. In 2005, the University of Lüneburg merged with the Fachhochschule Nordostniedersachsen. In 2013, the University of Cottbus merged with the Fachhochschule Lausitz.

Some of the universities successfully participating in the first wave and applying for the second wave were not considered for grants in the second wave.

No. of universities with ZK in the first wave: 9; No. of universities with ZK in the second wave: 11/No. of universities with GS in the first wave: 31; No. of universities with GS in the second wave: 30/No. of universities with EC in the first wave: 27; No. of universities with EC in the second wave: 30.

For instance, if a university successfully acquired a ZK fund it also had one GS and one EC. However, only the dummy variable “Excellent ZK” is set to one, as it reflects the most valued received fund. For a university only awarded for a GS and an EC concept, only the variable “Excellent GS” is set as one.

Further arguments for trend effects in student enrollment statistics are the possibility that students might follow the recommendations of their friends already studying at the relevant university or might follow universities that are currently “en vogue” (e.g. rankings).

In this model, the total number is set 0 if the promotion/relegation was defined as to be exceptional.

Thereby, the clubs are ranked continuously until 5th league (e.g. first place second league = 19; first place third league = 36 and so on, see Szymanski 2017), afterwards the rank is set as 200.

R2 values were estimated based on a simple fixed effect model.

Promotion to second division: men (2%|23%) vs women (4%|20%); Relegation to third division: men (−21%|−4%) vs women (−19%|−6%).

We also incorporated dummies for participation in the Champions League and the Europa League, without finding any significant results.

We also run simple fixed effect models. These models showed similar results regarding Enrollmentt−1, promotion and relegations, double graduation in the first year and the findings for the excellent initiative.

One argument against the results might be the missing control for other leisure activities. However, we controlled for external shocks, which should not be correlated with the provision of other leisure activities in the short run. In the long run, a successful sports team should certainly attract additional “satellite” leisure supplies such as bars or sport facilities, which attract additional students. Within 4 months, however, between the announcement of the shock and the enrollment activities, other leisure opportunities should be seen as constant. Furthermore, the opposite case (more leisure activities lead to sporting success and then to increasing the appeal of studying) does not seem convincing at all. To sum up this point, we assume the shocks through sporting success as to be exogenous, for which reason missing information regarding leisure statistics should cause no problem of omitting variable bias.

The incoming cash flows are usually no pure profits, since the 18.000€ are compensations for costs associated with the education of the students. However, if the students attracted by soccer clubs are assumed to be “on top” students, than the compensation fees are almost additional profits since an extra of 58 students will only cause little variable costs (e.g. opportunity costs), while fix costs (staff and facilities) are already paid. In addition, faced with a great number of student dropout in the bachelor programs at German universities, it seems reasonable to assume that the marginal benefits of an additional student might exceed the additional expenses due to the increasing number of students (Heublein 2014).

One might argue that, women are less likely to be soccer fans and thus the female enrollment rates should be less affected by soccer success. However, several arguments support our findings. First, female soccer has become quite popular among women with increasing female amateur clubs. Furthermore, women might be attracted by the additional non-use public good effects and by media attention, which might applies to non-soccer fans as well. Women might also follow their male friends who were attracted by soccer success.

Average population of clubs with promotion to first division: 1,022,862 (r = 0.12)/clubs with relegation from first to second division: 991,343 (r = 0.12)/clubs with promotion to second division: 263,594 (r = −0.06)/clubs with relegation from second to third division: 254,827 (−0.06). The overall correlation between population and student enrollments is low (r = 0.23).

Most German cities are rather unknown to foreign students. One particular way to become “known” is through the media coverage that is caused by participation in the first division. Often, only the top European divisions are mentioned on public television programs. If a university loses this means of prominence, foreign students might neglect these universities due to receiving less information about the city.

For instance, while sporting success is widely discussed in Germany in every newspaper and news source, foreign students would have to search for information in special websites in their native language.

References

Abbott A, Leslie D (2004) Recent trends in higher education applications and acceptances. Educ Econ 12:67–86

Anderson ML (2017) The benefits of college athletic success: an application of the propensity score design. Rev Econ Stat 99(1):119–134

Anderson TW, Hsiao C (1981) Estimation dynamic models with error components. J Am Stat Assoc 76:598–606

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment status. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation error-components models. J Econom 68:29–51

Arrow K (1973) Higher education as a filter. J Pub Econ 2:193–216

Baade RA, Dye RF (1988) An analysis of the economic rationale for public subsidization of sports stadiums. Annu Reg Sci 22:37–47

Baltagi BH (2008) Econometric analysis of panel data, 4th edn. Wiley, Chichester

Beckmann J, Langer MF (2009) Studieren in Ostdeutschland. Eine empirische Untersuchung der Bereitschaft zum Studium in den neuen Ländern. Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung Arbeitspapier 125

Beine M, Noël R, Ragot L (2014) Determinants of the international mobility of students. Econ Educ Rev 41:40–54

Belfield C, Boneva T, Rauh C, Shaw J (2016) Money or fun? Why students want to pursue further education. Money or fun? https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2826970

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87:115–143

Bobonis GJ, Finan F (2009) Neighborhood peer effects in secondary school enrollment decisions. Rev Econ Stat 91(4):695–716

Bond SR, Hoeffler A, Temple JR (2001) GMM estimation of empirical growth models. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=290522

Broecke S (2015) University rankings: do they matter in the UK? Educ Econ 23:137–161

Bruckmeier K, Fischer GB, Wigger BU (2013) Does distance matter. Tuition fees and enrollment of first-year students at German public universities. CESifo–CESifo Working Paper 4258

Brückner M, Pappa E (2015) News shocks in the data: Olympic Games and their macroeconomic effects. J Money Credit Bank 47(7):1339–1367

Buddelmeyer H, Jensen PH, Oguzoglu U, Webster E (2008) Fixed effects bias in panel data estimators. IZA Work Pap No. 3487

Büttner T, Kraus M, Rincke J (2003) Hochschulranglisten als Qualitätsindikatoren im Wettbewerb der Hochschulen. Vierteljahrshefte zur Wirtschaftsforschung 72:252–270

Cameron AC, Travedi PK (2010) Microeconomics using stata. Stata Press, College Station

Campbell DT, Stanley JC (1963) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Rand McNally & Company, Chicago

Castellanos Garcia P, García Villar J, Manuel Sánchez Santos J (2014) Economic crisis, sport success and willingness to pay: the case of a football club. Sport Bus Manag Int J 4:237–249

Castellanos P, García J, Sánchez JM (2011) The willingness to pay to keep a football club in a city: how important are the methodological issues? J Sports Econ 12:464–486

Castleman BL, Long BT (2016) Looking beyond enrollment: the causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. J Lab Econ 34:1023–1073

Chung DJ (2013) The dynamic advertising effect of collegiate athletics. Mark Sci 32:679–698

Cooper AC, Gimeno-Gascon FJ, Woo CY (1994) Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. J Bus Ventur 9(5):371–395

Crompton J (2004) Beyond economic impact: an alternative rationale for the public subsidy of major league sports facilities. J Sport Manag 18:40–58

Cubillo J, Sánchez J, Cerviño J (2006) International students’ decision-making process. Int J Educ Manag 20:101–115

Daily CM, Farewell S, Kumar G (2010) Factors influencing the university selection of international students. Ac Educ Lead J 14:59–75

Dreher A, Poutvaara P (2011) Foreign students and migration to the United States. World Dev 39(8):1294–1307

Drewes T, Michael C (2006) How do students choose a university?: an analysis of applications to universities in Ontario, Canada. Res Higher Educ 47:781–800

Eren O, Mocan N (2016) Emotional judges and unlucky juveniles. NBER Working Paper. http://www.nber.org/papers/w22611.pdf

Fabel O, Lehmann E, Warning S (2002) Der relative Vorteil deutscher wirtschaftswissenschaftlicher Fachbereiche im Wettbewerb um studentischen Zuspruch: Qualität des Studiengangs oder des Studienortes? Schmalenbachs Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung 54(6):509–526

Fischer M, Kampkötter P (2016) Effects of the German universities’ excellence initiative on ability sorting of students and perceptions of educational quality. CGS Working Paper. http://www.cgs.uni-koeln.de/fileadmin/wiso_fak/cgs/pdf/working_paper/cgswp_05-01-rev.pdf

Forrest D, Simmons R (2003) Sport and gambling. Oxford Review Economic Policy 19:598–611

Gibbons S, Vignoles A (2012) Geography, choice and participation in higher education in England. Reg Sci Urb Econ 42:98–113

Hachmeister CD, Harde ME, Langer MF (2007) Einflussfaktoren der Studienentscheidung. Eine empirische Studie von CHE und EINSTIEG. Arbeitspapier 65. http://www.che.de/downloads/Einfluss_auf_Studienentscheidung_AP95.pdf

Hamm R, Jäger A, Fischer C (2016) Fußball und Regionalentwicklung. Eine Analyse der regionalwirtschaftlichen Effekte eines Fußball-Bundesliga-Vereins-dargestellt am Beispiel des Borussia VfL 1900 Mönchengladbach. Raumforschung und Raumordnung 74(2):135–150

Heckman JJ (1977) Sample selection bias as a specification error (with an application to the estimation of labor supply functions)

Heine C, Willich J, Schneider H, Sommer D (2008) Studienanfänger im Wintersemester (2007/08). Wege zum Studium, Studien-und Hochschulwahl, Situation bei Studienbeginn. Forum Hochschule 16

Helbig M, Ulbricht L (2010) Perfekte Passung: Finden die besten Hochschulen die besten Studenten? Allgemeinbildung in Deutschland, pp 107–118

Helbig M, Jähnen S, Marczuk A (2017) Eine Frage des Wohnorts. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 46(1):55–70

Hemsley-Brown J, Oplatka I (2015) University choice: what do we know, what don’t we know and what do we still need to find out? Int J Educ Manag 29:254–274

Heublein U (2011). Entwicklungen beim internationalen Hochschulmarketing an deutschen Hochschulen. Michael Leszczensky/Tanja Barthelmes (Hg.), pp 119–130

Heublein U (2014) Student drop-out from german higher education institutions. Eur J Educ 49(4):497–513

Horstschräer J (2012) University rankings in action? The importance of rankings and an excellence competition for university choice of high-ability students. Econ Educ Rev 31:1162–1176

Hsiao C (2003) Analysis of panel data, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econom 115:53–74

Jäckle AE, Lynn P (2008) Respondent incentives in a multi-mode panel survey: cumulative effects on nonresponse and bias. Surv Methodol 34(4):105–117

Johnson BK (2008) The valuation of nonmarket benefits in sport. In: Humphreys BR, Howard DR (eds) The business of sports. Praeger, Westport, pp 207–233

Johnson BK, Whitehead JC (2000) Value of public goods from sports stadiums: the CVM approach. Cont Econ Pol 18:48–58

Johnson BK, Groothuis PA, Whitehead JC (2001) The value of public goods generated by a major league sports team. J Sports Econ 2:6–21

Johnson BK, Mondello MJ, Whitehead JC (2007) The value of public goods generated by a National Football League team. J Sport Manag 21:123

Judson RA, Owen AL (1999) Estimating dynamic panel data models: a guide for macroeconomists. Econ Lett 65:9–15

Kampkötter P, Fischer M (2016) Effects of the German universities’ excellence initiative on ability sorting of students and perceptions of educational quality. CGS Working Paper. http://www.cgs.uni-koeln.de/fileadmin/wiso_fak/cgs/pdf/working_paper/cgswp_05-01-rev.pdf

Kauppi N, Erkkilä T (2011) The struggle over global higher education: actors, institutions, and practices. Int Polit Soc 5:314–326

Kim W, Walker M (2012) Measuring the social impacts associated with Super Bowl XLIII: preliminary development of a psychic income scale. Sport Manag Rev 15(1):91–108

Kiviet JF (1995) On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 68:53–78

Krutilla JV (1967) Conservation reconsidered. Am Econ Rev 57:777–786

Lenton P (2015) Determining student satisfaction: an economic analysis of the National Student Survey. Econ Educ Rev 47:118–127

Levin A, Lin CF, Chu CSJ (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econom 108:1–24

Llewellyn-Smith C, McCabe VS (2008) What is the attraction for exchange students: the host destination or host university? Empirical evidence from a study of an Australian university. Int J Tour Res 10:593–607

Maringe F (2006) University and course choice: implications for positioning, recruitment and marketing. Int J Educ Manag 20:466–479

Mazzarol T, Soutar GN (2002) “‘Push–pull’ factors influencing international student destination choice. Int J Educ Manag 16:82–90

McCormick RE, Tinsley M (1987) Athletics versus academics? Evidence from SAT scores. J Polit Econ 95:1103–1116

McCrea R, Shyy TK, Stimson R (2006) What is the strength of the link between objective and subjective indicators of urban quality of life? Appl Res Qual Life 1:79–96

Merton RK (1968) The Matthew effect in science. Science 159:56–63

Mueller RE, Rockerbie D (2005) Determining demand for university education in Ontario by type of student. Econ Educ Rev 24:469–483

Nickell S (1981) Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica J Econom Soc 49:1417–1426

Obermeit K (2012) Students’ choice of universities in Germany: structure, factors and information sources used. J Mark Higher Educ 22:206–230

Petzold K, Moog P (2017) What shapes the intention to study abroad? An experimental approach. High Educ 1–20. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10734-017-0134-0.pdf

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879

Pope DG, Pope JC (2009) The impact of college sports success on the quantity and quality of student applications. South Econ J 75:750–780

Pope DG, Pope JC (2014) Understanding college application decisions why college sports success matters. J Sports Econ 15:107–131

Roodman D (2009) A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 71:135–158

Rowe D, McGuirk P (1999) Drunk for three weeks. Sporting success and city image. Int Rev Soci Sport 34:125–141

Schwester RW (2007) An examination of the public good externalities of professional athletic venues: justifications for public financing? Public Budg Financ 27:89–109

Siegfried J, Zimbalist A (2000) The economics of sports facilities and their communities. J Econ Perspect 14(3):95–114

Smith A (2005) Reimaging the city: the value of sport initiatives. Ann Tour Res 32(1):217–236

Soo KT, Elliott C (2010) Does price matter? Overseas students in UK higher education. Econ Educ Rev 29:553–565

Soutar GN, Turner JP (2002) Students’ preferences for university: a conjoint analysis. Int J Educ Manag 16:40–45

Spiess CK, Wrohlich K (2010) Does distance determine who attends a university in Germany? Econ Educ Rev 29(3):470–479

Storm RK, Thomsen F, Jakobsen TG (2016) Do they make a difference? Professional team sports clubs’ effects on migration and local growth: evidence from Denmark. Sport Manag Rev 20:285–295

Süssmuth B, Wagner S (2012) A market’s reward scheme, media attention, and the transitory success of managerial change. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 232(3):258–278

Süssmuth B, Heyne M, Maennig W (2010) Induced civic pride and integration. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 72:202–220

Szymanski S (2017) Entry into exit: insolvency in English professional football. Scott J Polit Econ. doi:10.1111/sjpe.12134

Tomlinson M (2012) Graduate employability: a review of conceptual and empirical themes. High Educ Policy 25:407–431

Tucker IB, Amato L (1993) Does big-time success in football or basketball affect SAT scores? Econ Educ Rev 12:177–181

Van Looy B, Ranga M, Callaert J, Debackere K, Zimmermann E (2004) Combining entrepreneurial and scientific performance in academia: towards a compounded and reciprocal Matthew-effect? Res Policy 33:425–441

Weimar D (2015) Sportindustrie als ökonomische Testumgebung. Diskussionsbeiträge der Mercator School Manag, No, p 398

Weimar D, Prinz J, Breithecker V, Dähn D (2013) Studiengangsbezogene Planspiele in der Oberstufe als Instrument zur Effizienzoptimierung des deutschen Hochschulwesens. Hochschulmanagement 9:64–70

Weimar D, Wicker P, Prinz J (2015) Membership in nonprofit sport clubs. A dynamic panel analysis of external organizational factors. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 44:417–436

Weisbrod BA (1964) Collective-consumption services of individual-consumption goods. Q J Econ 78:471–477

Wicker P, Hallmann K, Breuer C, Feiler S (2012a) The value of Olympic success and the intangible effects of sport events—a contingent valuation approach in Germany. Eur Sport Manag Q 12:337–355

Wicker P, Prinz J, von Hanau T (2012b) Estimating the value of national sporting success. Sport Manag Rev 15:200–210

Wicker P, Whitehead JC, Johnson BK, Mason DS (2015) Willingness-to-pay for sporting success of football Bundesliga teams. Contemp Econ Policy 34:446–462

Wicker P, Whitehead JC, Johnson BK, Mason DS (2017) The effect of sporting success and management failure on attendance demand in the Bundesliga: a revealed and stated preference travel cost approach. Appl Econ 49(52):5287–5295

Wilkins S, Balakrishnan MS, Huisman J (2012) Student choice in higher education: motivations for choosing to study at an international branch campus. J Stud Int Educ 16:413–433

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. J Econom 126:25–51

Wooldridge JM (2015) Introductory econometrics, 6th edn. South-Western Cengage Learning, Michigan

Zhang L (2010) The use of panel data models in higher education policy studies. In: Smart J (ed) Higher education: handbook of theory and research. Springer, The Netherlands, pp 307–349

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding has been requested.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest or any financial interest or benefit we have arising from the direct applications of our research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weimar, D., Schauberger, M. The impact of sporting success on student enrollment. J Bus Econ 88, 731–764 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0877-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0877-1