Abstract

A large and growing number of international organizations (IOs) are made up and governed by illiberal or outright authoritarian regimes. Many of these authoritarian IOs (AIOs) formally adopt good governance mandates, linking goals like democracy promotion, anti-corruption policies and human rights to their broader mission. Why do some AIOs adopt good governance mandates that appear to conflict with the norms and standards these regimes apply at home? We argue that AIOs adopt good governance mandates when they face substantial pressure from inside or outside the IO to adopt them. Central to our argument is that not all aspects of good governance are inherently or equally threatening to autocratic regimes. They pursue strategies that minimize the threat by externalizing policy outside the membership and strategically defining the goals to avoid or enact. This allows autocratic governments to uptake good governance talk but lessen any deep commitment to the norms and sometimes even to use them strategically to project their own power outside of the organization. Using data on 48 regional IOs with primarily autocratic membership between 1945 and 2015, we demonstrate that AIOs facing pressure from external good governance promoters will adopt good governance mandates but strategically shape those mandates in their favor if they can form bargaining coalitions with like-minded governments. The findings have sobering implications for the future of good governance promotion through IOs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since World War II, international organizations (IOs) have been a central component of the U.S.-led international liberal order. Today, they are ubiquitous. Within and beyond their membership, IOs have contributed to the rise and spread of both economic and political liberalization, providing the conditions and infrastructure for states to coordinate, regulate, and delegate their various efforts to promote, among other things, free trade, climate protections, democracy, and peace and security (Checkel, 2001; Hafner-Burton, 2005, 2013; Haftel, 2007; Mansfield & Pevehouse, 2006, 2008; Pevehouse, 2002a, b, 2005; Poast and Urpelainen 2015, 2018). Many of these Western-driven organizations have adopted formal “good governance” mandates, which advance the liberal agenda by linking goals like democracy promotion, anti-corruption policies, and human rights to an organization’s broader mission (Ferry et al., 2020; Greenhill, 2015; Hafner-Burton and Schneider 2019; Pevehouse, 2002a, 2005; Stapel, 2022). That is at least the goal.

In recent years, a large and growing number of organizations are made up and governed by illiberal or outright authoritarian regimes (Cottiero, 2021; Cottiero and Haggard 2023; Debre, 2021a, b; Obydenkova and Libman 2019). While it may not be surprising that IOs dominated by highly democratic member states have led the charge to legalize good governance mandates into their organizations, it is surprising that many IOs that are composed of mainly autocratic states also formally adopt these standards. For example, the African Union (A.U.), an organization composed of many autocratic members, has steadily adopted formal standards pertaining to the protection of human rights, the promotion of democratic principles and institutions, and the rule of law. Given that so many of the African Union’s members blatantly violate these norms, why would the organization adopt good governance mandates? More generally, why do authoritarian IOs (AIOs) with majority non-democratic membership adopt good governance mandates that would appear to conflict with the very norms and standards these regimes apply at home?Footnote 1

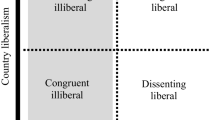

Our starting assumption is that authoritarian governments do not want their IOs to adopt formally institutionalized good governance mandates that create rules and procedures around democracy promotion, the rule of law, civil society, or human rights. These governments are sensitive to any potential sovereignty costs imposed by these mandates that create common rules and expectations (Hafner-Burton, Mansfield, and Pevehouse 2023; Panke et al., 2020; Stapel, 2022). The ability of AIO members to maintain these preferences in IOs depends on their ability to assert themselves against pressures from both within and outside. First, the likelihood that AIOs adopt good governance mandates, and especially those that target their own membership, depends on the autocratic members’ ability to navigate the institutional decision-making process to their advantage. AIOs are quite diverse in their compositions. Some, like the Arab League, are comprised mainly of highly autocratic states, while others like the Southern African Development Community (SADC) or the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) include a mix of autocrats, hybrid regimes, and other forms of electoral anocracies that may be more supportive of (or less resistant to) governance standards. This heterogeneity of membership types within an AIO shapes the winning coalition for adopting or rejecting governance mandates. Whereas democratic members may have a positive influence on the adoption of good governance mandates in AIOs with a larger share of democratic member states, and hybrid regimes may be more willing to adopt good governance standards themselves, AIOs with a greater share of more deeply autocratic members are less likely to adopt good governance standards. Second, the members of many AIOs face pressures from foreign good governance promoters, such as other states and organizations that seek to proffer these values and provide financial or other diplomatic benefits to members or the AIO itself. When a substantial portion of the membership is beholden to external good governance promoters, even autocrats in these organizations may feel pressured to adopt these otherwise unwanted mandates.

Our key insight is that even if AIOs adopt good governance standards, their autocratic members will try to strategically minimize the costs of mandate adoption in two ways. First, they favor a portfolio of mandates with an externally focused jurisdiction, empowering the membership to act with an institutional reach beyond their collective borders, minimizing the potential domestic costs on the members. This allows AIOs to uptake good governance talk and even use it to project their own power and interests outside of the organization. Second, AIOs are also strategic about the issue areas that they are willing to adopt. Good governance is a broad category of norms, not all of which are necessarily or equally contrary to autocratic rule. These organizations will be very unlikely to adopt mandates that explicitly promote liberal modes of governance, such as democracy, human rights, free elections, or protection of civil society. Yet, they may be more willing to adopt mandates involving other forms of good governance talk, such as anti-corruption standards, that are less threatening to autocratic rule, could be more easily neutralized, or that could even be used against internal opposition to the regime.

To test the empirical implications of our argument, we leverage data on the uptake of good governance standards in 48 regional AIOs with majority autocratic membership between 1945 and 2015 (Panke et al., 2020). We show that AIOs are more likely to adopt mandates when the winning coalition is less solidly authoritarian (more mixed) or dependent on promoters. But, crucially, they are less likely to adopt internal mandates than their less autocratic counterparts, favoring external jurisdiction to avoid potential sovereignty costs. Whereas they try to minimize the costs of adoption by externalizing good governance standards, the findings indicate that autocratic AIO members try to avoid the adoption (and externalize) all types of good governance mandates. The results are robust to alternative conceptualizations of AIOs and alternative operationalizations of the main explanatory variable as well as to different model specifications (including controlling for selection processes), and the inclusion of additional control variables.

The findings contribute to the emerging literature on AIOs (Cottiero, 2021; Cottiero and Haggard 2023; Debre, 2021a, b; Obydenkova and Libman 2019). This work illustrates the rise of illiberal IOs and provides insights into some of the consequences for international cooperation and domestic politics. Like other works in this vein, we highlight that AIOs have heterogeneous membership. They can include members with various domestic political institutions, with important implications for the design of these AIOs, their scope, and cooperation outcomes. By acknowledging that jurisdiction of mandates might vary, we offer new insights into the strategies that autocratic member states pursue to assert their interests within AIOs, and the constraints that they encounter when doing so.

The implications of these findings are both promising and perhaps ultimately sobering for the uptake of good governance mandates by AIOs. On a promising note, despite the odds, good governance promotion by powerful actors has a positive effect on the uptake of good governance mandates.Footnote 2 AIOs adopt mandates when more democratic members can assert themselves in the decision-making process or when the AIO is beholden to foreign actors who seek to spread liberal principles. Although their member states espouse anti-democratic positions and policies at home, a growing number of AIOs embed some form of good governance into primary law, creating a legal basis for these AIOs to act in some areas of governance. Sobering, though, is the fact that these organizations are strategic in how they do so. They tend to avoid the core elements associated with democracy promotion and prefer to externalize policy, providing a potential tool kit to use these mandates to shame or bully others rather than to make commitments within the membership.

If the rise of authoritarianism continues, AIOs might become less willing to adopt internal good governance mandates with tremendous implications for good governance around the globe. Although beyond the scope of this paper, our analysis raises the critical question of whether these mandates have any positive effect on the actual good governance practices of their membership. At the end of the day, they may do little to affect positive change internally and may even be used perniciously against others.

1 Good governance mandates

Talk of “good governance” is common (Barnett, Pevehouse, and Raustiala 2021, Chap. 1; Keping, 2018; Woods, 1999). Starting with the defeat of the axis powers in World War II, and especially with the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War, political calls for good governance have been made far and wide. U.N. secretary generals have claimed that it is “the single most important factor in eradicating poverty and promoting development,” while the bureaus of other powerful IOs like the World Bank have drawn global attention to the concept (United Nations, 1998; Wolfensohn, 1996; World Bank, 1992). While there is no singular or universally accepted definition, the United Nations identifies eight principles on which good governance should rest: participatory, consensus oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, effective and efficient, equitable and inclusive, and supports the rule of law. And it encompasses, at least in principle, a wide array of policies to protect human rights, fight corruption, and promote human development and well-being. Still, the concept is nebulous and has many interpretations, not all of which are in sync with standard features of democracy promotion.

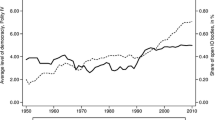

Over time, a growing number of IOs have put themselves at the forefront of efforts to promote good governance (Stapel, 2022). Figure 1 illustrates the historical rise in the number of good governance standards adopted across all IOs in our sample, with a clear surge after the end of the Cold War. Many have by now crafted formal policies stating the intent to encourage better governance in some form or another. There are over 285 good governance mandates adopted and promoted across the 76 IOs in our full sample (Panke et al., 2020). These policies, which we refer to as mandates, include the 1999 OECD Anti-Bribery Convention making the bribery of foreign public officials involved in international business transactions a crime (Elliott, 1997, 7–27); the Southern African Development Committee has adopted extensive democracy governance principles to implement the requirements of that organization’s founding treaty (Pevehouse, 2002a, 212–13); and the many IOs that formally link human rights policies to their other economic or political missions (Hafner-Burton et al., 2015). Most famous in this regard is the EU, where good governance is explicitly used to ensure applicants’ suitability for membership along many dimensions, including democracy and human rights (Kelley, 2004; Schimmelfennig, 2008; Schneider, 2007, 2009).

For reasons already well explored in the literature, it is not surprising that democratic IOs embrace formal good governance mandates that contain some degree of sovereignty costs. Many democracies already display some metric of good governance practices at home, and the additional sovereignty costs of an IO mandate may effectively be small on them. Good governance mandates can offer various benefits for democracies. Respect for the rights enshrined in these mandates, such as human rights, political liberties, and the rule of law, is a keystone of democracy. Democracies may want such policy competency within their IOs to (i) signal their commitment to those policies that underpin their own system of rule (Pevehouse, 2005), (ii) tie the hands of other democratic members, especially those undergoing the challenging process of democratization (Hafner-Burton et al., 2015), (iii) publicize and spread their own democratic norms, values, and policies beyond their own borders (Checkel, 1999; Finnemore, 1993, 1996), and (iv) they may also take on these mandates in response to domestic political pressures and in support of broader foreign policy goals (Hathaway, 2007).

Good governance mandates are not just a tool for democratically-led IOs (DIOs); they vary in the types of states and organizations that adopt them. Figure 2 illustrates that the Western-led group of IOs like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or the European Union are not alone in adopting these mandates. In fact, AIOs (plotted over year by the dotted line) are as likely to adopt good governance standards as are DIOs (plotted over year by the solid line).Footnote 3 The largest share of these standards is adopted by regional organizations in Africa, such as the 2006 African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, which addresses corruption in both public and private sectors among the membership. Many of these organizations are led by autocrats. But AIOs from other regions are doing the same.

One possible explanation is that good governance mandates are costless to adopt for members in AIOs, because they will never be enforced and are nothing more than cheap talk. That view would be consistent with a growing literature on the uptake of human rights treaties by autocratic regimes (Cole, 2005; Hafner-Burton, 2012; Lupu, 2015; Neumayer, 2005; Vreeland, 2008). Yet, the cheap talk argument is inconsistent with the fact that even AIOs impose at least some degree of “sovereignty costs” on their membership when they surrender discretion over national policies to adhere to the standards set by an organization (Moravcsik, 2000). They certainly impose some transaction costs to adopt (Abbot and Snidal 2000). Most IOs are characterized by some formal degree of legalism, which is promoted by rule specificity, issue linkage, membership restrictions, formal reporting, monitoring of behavior, and enforcement procedures. At least in the field of human rights, they place some constraints on members’ sovereignty, even among autocrats (Hafner-Burton et al., 2015, 2023). These mandates also serve as a focal point for international good governance promoters or the domestic opposition who can use them as a tool against the government. The mandates thus serve as a nascent weapon to be used against autocratic regimes at some time in the future. There are also non-trivial transaction costs associated with institutional contracting and bargaining over these policies (Abbott and Snidal 2000). If the answer to our puzzle is not simply that these mandates are entirely costless for AIOs to adopt and easy to circumvent, what then explains their growth, and the variation in adoption by autocrats?Footnote 4

Central to the argument we articulate in detail below is that not all aspects of good governance are equally threatening to autocratic regimes. We highlight two ways in which AIOs strategically seek to reduce the sovereignty costs that might come with organizational commitments to good governance. First, these good governance mandates have various audiences and jurisdictions. Some are internally focused on good governance among the membership of the organization. They create policies and procedures that apply only to the participants of the IO, for example, creating common rules and norms around anti-corruption policy within member states, as the OECD’s Anti-Bribery Convention does. They may even create the authority for members of an IO to coordinate actions within their borders. Others are externally focused, creating common positions for international actions and negotiations outside the scope of membership. One example is the Asia Cooperation Dialogue, which has adopted several good governance mandates that target non-members. Similarly, the Arab League, the European Union, the African Union, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations have all adopted mandates on civil liberties, corruption, human rights, or the rule of law that target countries beyond their membership. Some, such as the European Union, have both internal and external jurisdictions on good governance. Figure 3 illustrates the number of internal versus external good governance mandates in the sample of 76 IOs over time. Although most mandates target the IO membership internally, increasingly IOs have also adopted good governance mandates with a jurisdiction beyond their membership. In 2015, 23% of good governance standards were externally focused, which is a marked historical shift.

Second, these mandates vary on substance. Good governance is a very broad and seemingly all-encompassing term that does not simply equate to democracy promotion alone. According to the United Nations, it “refers to all processes of governing, the institutions, processes and practices through which issues of common concern are decided upon and regulated.”Footnote 5 This is an exceptionally broad definition, which means that different actors can use the term to encompass different substantive areas and intentions. Democracy, human rights, and civil society are all aspects of good governance policy. But so are transparency and accountability, the rule of law, and norms against corruption. Important to the argument we develop is that the substance of different types of mandates bears differently on the issue of democracy promotion. Some mandates are more explicitly tied to promoting core norms of liberal democratic governance than others.

Fortunately, our data allow us to distinguish the substantive focus of these mandates. Figure 4 graphs the number of adopted mandates, distinguishing between the group of mandates that have a direct connection to codified norms of democracy promotion (Democracy) and those mandates that are less centrally focused on liberal democracy per se but revolve around other aspects of bureaucratic good governance that may be more compatible with autocratic styles (Bureaucracy). Conceptually, the good governance data we depict in this figure as promoting Democracy include standard institutional concepts such as civil and political rights, civil society, democracy, discrimination, freedom, freedom of the press, fundamental rights, basic rights, human rights, liberty, peoples’ rights, separation of powers, independent judiciary, and free and fair elections. By contrast, the data we depict in the category we call Bureaucracy are more connected to issues of corruption, good governance, political stability, the rule of law, transparency, and accountability. Mandates that seek active promotion of democracy and human rights—that are concretely defined by international law—are more threatening to autocratic rule than are mandates in the latter category, which are less concretely defined by law, leave ample room for interpretation, and may even be valuable to an autocratic regime. For example, it is well understood that even the most autocratic of governments may actively seek to use corruption speak—and specifically anti-corruption talk—to “deter ideologically disaffected members of the populace from entering the bureaucracy. Anticorruption institutions act as a commitment by the elite to restrict the monetary benefits from bureaucratic office, thus ensuring that only zealous supporters of the elite will pursue democratic posts (Hollyer and Wantchekon 2015). The graph shows that even though IOs have focused on implementing democracy-promoting mandates, increasingly they have adopted more bureaucracy-focused mandates as well.

2 Enlightened dictators?

We contend that autocratic governments tend to oppose good governance mandates and want to minimize the potential costs those mandates impose on them. However, AIOs tend to be heterogenous in membership, typically including a mix of democratic and autocratic members. This internal heterogeneity, coupled with the pressure from outside good governance promoters, can explain why some autocratic members are more successful than others in being able to avoid, externalize, or strategically define the costs and content of good governance mandates.

2.1 Why autocratic governments oppose good Governance mandates

It is well established that states value and support governance styles that are like their own, for both normative and strategic reasons. Previous research shows that IOs composed of democratic, corrupt, or human-rights-advocating governments have created and attempted to enforce norms and policies designed to foster similar forms of governance within IOs. They have done so to push their collective values, assuage or support like-minded domestic interest groups, and foster peace and security internally or abroad (Ferry et al., 2020; Greenhill, 2015; Hafner-Burton and Schneider 2019; Pevehouse, 2002a).Footnote 6

None of this holds for highly autocratic states. For them, good governance is not a concept the leadership values, embraces, or seeks to spread domestically or abroad. The opposite—clamping down against good governance norms (especially against things like democracy promotion, human rights, civil society, and free and fair elections)—is how autocrats try to survive internally (Hafner-Burton et al., 2014, 2018). Most face little meaningful pressure and scrutiny from their domestic selectorates concerning the adoption of these standards, especially regarding foreign policy. In many cases, the domestic selectorate of an autocratic state does not represent or reflect the general will of the people but rather a small group of political or business elites (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003; Weeks, 2008). Even if the average citizen had an opinion about their government’s foreign policy, it would be unlikely to generate negative externalities for a government that seeks to avoid making such commitments in IOs. It is not even clear that the kinds of standards autocrats adopt in IOs would even register in the public mind as something to care about. Moreover, public outcry or efforts to criticize the government through media would almost certainly be suppressed (King et al., 2013). Electoral consequences are highly unlikely or even impossible. Autocrats have utilized IOs to support their political survival at home (Cottiero, 2021) and prevent democratization efforts (Debre, 2021a; Obydenkova and Libman 2019), thereby fostering a process of authoritarian consolidation (Cottiero and Haggard 2023).

For other, less autocratic regimes, good governance standards may not seem so antithetical to their interests. Anocrats or other hybrid regimes seeking legitimacy through domestic elections might favor IO standards that signal to voters (or others) that the leadership is conscientious (whether truthfully or not) to publicize norms of good governance externally. If they do not rule with an iron fist, these types of illiberal regimes may face genuine threats to their hold on power at the polls (or elsewhere) if public opinion does not support them. In fact, there is significant evidence to suggest that these types of mixed regimes—neither fully democratic nor autocratic—are precisely the ones committing to norms such as democracy or human rights (Hafner-Burton et al., 2015; Pevehouse, 2005). While these regimes may not all be equally enthusiastic about adopting good governance mandates, they are less resistant than stable autocrats to the idea and there could be real benefits.

2.2 Why illiberal IOs adopt good Governance mandates

The preferences over good governance policies are reflected in governments’ attempts to use IOs to proffer their preferred policies and norms at home and abroad. We argue that whether they succeed depends on the ability of authoritarian states to assert themselves against pressures within and outside the AIO.

Internal pressures

Given the difference in preferences over good governance policy across different types of illiberalism, both the multilateral context and the decision-making process within most IOs matters. While the multilateral nature of negotiations can minimize strategic interests, state interests can still manifest themselves when powerful states or groups of states are present or when member states have homogenous interests (Schneider & Tobin, 2013). Groups of autocratic states negotiating policy in an IO are not likely to adopt good governance standards that they themselves do not support or are willing to implement domestically. That probability increases, however, when an AIO becomes decidedly less dominated by a strictly autocratic winning coalition that can dominate the policymaking process. If the AIO includes a greater share of democratic or hybrid member states, these states will be more effective in pushing in favor of the adoption of good governance standards. But as the share of autocratic members in the AIO increases, autocrats will be more able to assert themselves against the adoption of good governance mandates, all else equal. Therefore, AIOs are less likely to adopt good governance mandates when the winning coalition within the AIO becomes more solidly authoritarian, meaning that autocrats dominate the membership composition (Hypothesis 1). They are more likely to do so when the AIO includes a mix of hybrid regimes and other forms of electoral anocracies that are not solidly democratic but may be less resistant or even amendable to standards that counteract democratic backsliding or send external signals about intent.

One prominent example is the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), an organization that includes a heterogeneous mixture of more and less democratic member states.Footnote 7 Since 2005, ECOWAS has been a regional leader in adopting good governance mandates, especially on the promotion and protection of human rights within the organization’s jurisdiction. In part, this has been driven be the desire among the more democratic members of the organization to create credible commitments to reign in autocratic-leaning members when they violate basic governance norms. The organization has been active in implementing its mandate. The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice has issued path-breaking judgements against the IO’s own membership, imposing sanctions on Mali when the military postponed the 2022 presidential elections (Avoulete, 2022) and taking punitive actions against members such as Niger for condoning certain forms of slavery and Gambia for torturing journalists (Alter et al., 2013).

External pressures

In addition to the internal decision-making process, which is crucial in explaining decisions by AIOs with respect to good governance, we argue that external pressure can lead AIOs to sway toward the adoption of mandates. Many regional IOs have received significant pressure and funding from external good governance promoters. Since World War II, the promotion of good governance has become a central pillar in the U.S.-led international liberal order, and many countries and IOs—most notable in this respect are the European Union, the World Bank, and the United States—have tried to promote good governance around the globe using carrots and sticks such as foreign aid and trade (Hafner-Burton, 2005, 2009; Kuziemko and Werker 2006; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith 2009; Schneider and Urpelainen 2013). If members of IOs are dependent on those actors, external good governance promoters can support the adoption of good governance mandates, promising rewards for adopting them and threatening recalcitrant states with punitive consequences. Promoters can offer foreign aid (or threaten withdrawal thereof), they can apply trade or military sanctions, use strategic issue linkages, or offer special deals to increase third parties’ incentives to adopt good governance mandates. The EU, for instance, offers aid and other economic and political benefits to potential members that align with the IO’s global governance goals and mandates. It also withholds aid and trade and imposes sanctions readily on EU members, potential candidate countries, and development partners that abuse basic global governance norms and practices. While not perfectly consistent, the EU is a powerful global governance norm promoter both internally, in the region, and globally through the provision of material incentives. In addition, powerful promoters also benefit from indirect or passive influence. If members of an IO have close security ties to the promoter or are dependent on the promoter’s foreign aid, they will be inclined to align with the promoters’ preferences because they anticipate that undermining the promoter’s strategy may ultimately have consequences for future aid allocation (or other relevant) decisions.

Empirically, a plurality of members of AIOs are more likely to be beholden to foreign good governance promoters than a small number of wealthy autocratic states such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Many autocrats in developing countries seek financial, diplomatic, or security-related support of promoters like the European Union, the OECD, or the United States. Many receive foreign aid or are heavily trade dependent on governments and institutions that want to see evidence that good governance issues are being talked about. These promoters, of course, also spearhead the movement to adopt these standards in the first place and seek to use their influence to spread their norms and values. Sometimes, they even directly fund the IOs in question (Gray, 2018), making the uptake of good governance standards all but a necessity. That is why (Hypothesis 2), AIOs are more likely to adopt mandates when the membership is beholden to foreign good governance promoters.

A prominent example of this hypothesis is the African Union and its deep historical dependence on the European Union and its legacy of colonization (Nagar and Nganje 2016; Stout, 2020). As far back as the European Union’s Cotonou Agreement in 2000 with the 79-country bloc of African, Caribbean, and Pacific states, Europe has formally tied its own vision of good governance into almost all aspects of its relations with the regions, ruled by many longstanding dictators amidst sporadic efforts at democratization (Börzel et al., 2008; Carbone 2012: 13; Hafner-Burton, 2005). Today, the African Union, which was modeled in many ways on the European Union’s own institutions, is a prime example of an AIO that has embedded many forms of good governance standards into its institutions, in part pressured and guided by European requirements for development aid, trade, assistance and diplomacy to the continent (TNI, 2000). Another prominent example is the adoption of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards, with both mandatory and voluntary reporting disclosures, by the Asian Infrastructure Bank, which was required to get European buy-in. These first two hypotheses provide the foundation on which we now develop the more novel contribution of the paper. Given that AIOs will at times adopt good governance mandates, how exactly will they design them to minimize unwanted costs?

2.3 Under pressure? How autocratic IOs minimize the costs of adoption

Our argument about variation in good governance mandate adoption across AIOs assumes that autocratic regimes, such as the many autocratic members of the African Union, face at least some costs for adopting and then violating good governance mandates, especially when they impose domestic costs on governments. However, our central argument is that not all good governance mandates impose similar costs, which provides incentives and opportunities for autocratic governments under pressure to be strategic about the types of mandates and the targets of the mandates they agree to adopt. The costs of the mandates may vary in two ways: jurisdiction and substance.

First, to minimize the potential costs of good governance mandates, illiberal regimes will be strategic about the jurisdiction of the rules they support in their AIOs. Some rules are inward facing, providing the organization with the jurisdiction and competence to apply the rules internally with respect to the AIO membership, as the ECOWAS and AIB examples illustrate. Others, however, are outward facing, developing common positions and articulating them, for instance, in international negotiations or with other states. These external jurisdictions empower AIOs and their members to act beyond their own borders. These categories are not mutually exclusive but rather operate as a portfolio, as many AIO mandates include both internal and external jurisdictions. External mandates are not only less likely to impose direct costs on illiberal regimes within the AIO, but they can even offer added benefits through the ability to impose costs on other states and as an avenue to project state power and sovereignty outside of the organization.

Because groups of highly autocratic states are the least likely of all to adopt good governance standards that impose any sovereignty costs on their own regimes, they should be less likely to favor internal mandates than their democratically elected counterparts. When autocratic members are more able to form a winning coalition, they should be more likely to implement external mandates, if any mandates at all. Consequently, we hypothesize that AIOs will be more likely to adopt a portfolio that leans toward good governance mandates that provide more external leverage and application when the winning coalition within the AIO becomes more solidly authoritarian (Hypothesis 3).

The African Union again provides a relevant illustration of the argument. Partly at the directive of global governance norm promoters, such as the European Union, the African Union has adopted a variety of internally focused policies on human rights, anti-corruption and other good governance standards for the continent. But the African Union has also strategically crafted a series of good governance mandates with external intentions and jurisdiction in order to impose costs on other countries that have harmed the continent’s interests, as well as to better promote and project the organization’s authority in world affairs. For example, in 2020, as a part of the African Union’s good governance theme to win the fight against corruption, it adopted the Common African Position on Asset Recovery (CAPAR), which is a policy to combat and reverse illicit financial flows out of Africa. It calls for the detection and identification of assets; the recovery and return of assets; management of recovered assets; and cooperation and partnerships to recover and return African assets. Among other things, the mandate calls “upon international partners and allies to agree on a transparent and efficient timetable for the recovery and return of stolen assets to Africa.”Footnote 8 According to the organization, today, “CAPAR is the bedrock for our continent’s legal instrument and technical framework for negotiating the return of our stolen assets and illicit capital flights, taken illegally out of our shores and hosted in foreign jurisdictions.”Footnote 9 It is an externally focused mandate that seeks to change other states’ behavior, and is explicitly labelled as a “good governance” policy.

The African Union has also been strategic in adopting good governance mandates to project power and influence. Its Agenda 2063 was crafted with the express intention of “adding African voices to global governance policy formulation and decision making,” as well as to further the African Union’s goal to become “a strong, united, resilient and influential global player and partner.” This overtly includes the desire to boost the organization’s collective action in global negotiations through pooling sovereignty and better integration.Footnote 10 One of the core pillars of this mandate includes “good governance.” Spoken aspirations include efforts to mobilize support for the endorsement of African candidates for top posts in the international system and to better integrate A.U. members into global diplomacy. Effectively, the mandate is an effort to project greater international influence and power to better represent the African people and continent, all in the name of good governance.

The A.U. examples suggest another way in which AIOs may behave strategically to minimize the potential costs of good governance mandates, by targeting certain issue areas within the concept of “good governance” that are less associated with democracy and liberal rule. Of the diverse substantive areas covered by global governance mandates, we might expect AIOs to avoid some at all costs (whether internal or external in focus), especially those focused on standard elements of democracy promotion such as human rights, free elections, civil rights, and protection of civil society. As described earlier, these concepts are defined by international law, thus have at least some common standing and formal interpretation. And they are all directly antithetical to the very systems that underpin authoritarian rule.

Other issues that commonly fall into the bucket of “good governance,” by contrast, may be less inimical to autocratic rule. Mandates against corruption or for liberty, the rule of law, political stability or transparency could be innocuous for most autocrats and in theory may even be advantageous for some autocratic states. Anti-corruption or transparency standards are often used by autocratic governments to disempower their political opposition. For example, dictators frequently imprison their political opposition on corruption charges (whether true allegations or not). And terms like “liberty” have no direct classification in international law and so can be broadly interpreted to a regime’s advantage—for example, liberty from interference. That is why we expect that AIOs are less likely to adopt mandates involving more directly pro-democratic issues when the winning coalition within the AIO becomes more solidly authoritarian (Hypothesis 4), opting instead for more malleable bureaucratic concepts that are open to greater interpretation.

3 Research design

To assess our hypotheses, we turn to observational data on good governance mandates adopted by 76 regional intergovernmental organizations from 1945 to 2015 (Panke et al., 2020).Footnote 11 Our level of analysis is the AIO-year. Since we are interested in the decision-making outcomes within AIOs, our sample is restricted to AIO-years in which the membership is autocratic.Footnote 12 To conceptualize authoritarian regional organizations, we focus on the regime type of their member states, capturing the identity–and preferences–of their members. We define authoritarian regional organizations as regional organizations that have a membership which is authoritarian, by majority. This choice reflects the theoretical presumption that member state governments are the principals who take decisions and delegate powers, and that the regime type of those principals has implications for what these organizations do. A growing body of literature has demonstrated that ROs with authoritarian members are more likely to materially support and legitimize the authoritarian status quo in their member states (Cottiero and Haggard 2023; Debre, 2021a, b; Obydenkova and Libman 2019; von Soest, 2015; Tansey, 2016).

To identify authoritarian IOs, we start with the regime type of each member state, and then aggregate to get the percentage of members that are autocratic in a given IO and year. To measure regime type, we use the V-Dem polyarchy index, which reflects a somewhat more minimalist or “electoral” conception of democracy. The polyarchy index aggregates measures of governments’ respect for “freedom of association, suffrage, clean elections, [an] elected executive, and freedom of expression and alternative sources of information.” In contrast to the more demanding liberal democracy index, polyarchy scores omit measures of horizontal checks or rule of law. Mean scores close to zero indicate deeply authoritarian regimes with no electoral competition and severe restrictions on political freedoms. Scores closer to one reflect democratic governments that fully reflect the norms of an electoral democracy.Footnote 13 We consider IOs to be autocratic if the majority of members are autocratic.Footnote 14 This would allow the membership to make decisions that favor the preferences and policy ideas of more autocratic governments. Of the 76 IOs in the sample, 48 IOs are autocratic.Footnote 15

Dependent variables

We generate dependent variables about scope (or the number of mandates), externalization (or jurisdiction), and mandate type (or substance) using good governance mandate data from Panke et al. (2020). This dataset codes good governance mandates in IOs with respect to 14 indicators of good governance: civil or political rights, civil society, corruption, democracy and democracy promotion, discrimination, free and fair elections, freedom of the press, (fundamental) freedoms, human rights, liberty, people’s rights, political stability, rule of law, separation of powers and independence of the judiciary, transparency, and accountability. It also codes the jurisdiction of these mandates, which can apply to the membership of the IO (internal mandates) or beyond the membership of the IO (external mandates). First, we measure the total number of good governance mandates to analyze the determinants of the Scope of all governance mandates for Hypotheses 1 and 2. If AIOs do adopt good governance mandates, they do so strategically by engineering both jurisdiction (Hypothesis 3) and substance (Hypothesis 4) to minimize the sovereignty costs on their own members.

We evaluate the latter two hypotheses using three variables. To analyze the determinants of the portfolio of good governance mandates regarding jurisdiction, we create the variable Externalization by subtracting the number of internally oriented governance conditions from the number of externally oriented good governance mandates. To analyze whether more autocratic AIOs are more likely to avoid mandates involving directly pro-democratic issues, we count the total number of governance conditions for all mandates that involve issues of civil rights, political rights, civil society, democracy, discrimination, freedom, freedom of the press, fundamental rights, basic rights, human rights, liberty, peoples’ rights, separation of powers, judiciary, and elections (Democracy). We also generate a variable (Bureaucracy) to group the mandates that should be less costly—and possibly even beneficial—to autocratic member states. The variable counts mandates involving issues of corruption, good governance, political stability, the rule of law, transparency, and accountability. As previously discussed, we expect those mandates that are more explicitly tied to core norms of democratic governance—like democracy promotion, human rights, civil society, and free and fair elections—to be eschewed by AIOs versus those mandates that focus on more general issues like corruption or other categories of good governance that could more readily be used by autocratic regimes against their internal opposition, or just neutralized through interpretation (Hollyer and Wantchekon 2015).

There is a great deal of variation in the scope of good governance mandates across AIOs and time. Although some AIOs have no mandates, surprisingly many have adopted a range of good governance standards. In fact, the average number of good governance standards adopted in AIOs is four (ranging from 0 to 23), which is slightly above the average number of good governance mandates adopted in democratic IOs (three, ranging from 0 to 18). Similarly, there is significant variation in the extent to which AIOs choose external over internal mandates and bureaucracy over democracy mandates.

Explanatory variables

To establish the influence of bargaining coalitions (Hypotheses 1, 3, and 4), we measure the percentage of autocratic members within each AIO. The more autocratic members are within an AIO, the more successful they should be to assert their preferences in the decision-making process. For example, we would expect that AIOs with fully autocratic membership to be much more likely to resist pressures to adopt mandates and to minimize the costs of good governance mandates than AIOs that still have significant democratic membership. To model the strength of autocratic bargaining coalitions, we take the average of each country member’s democracy score as measured by V-DEM, using their polyarchy index (Coppedge et al., 2022). We then compute the percentage of countries that can be considered autocratic according to the V-DEM coding (those with polyarchy values less than 0.5).Footnote 16 It is commonly accepted in the literature that more powerful IO members have greater ability to influence IO decisions, including monitoring and enforcement, and they may also have greater leverage to influence decisions over good governance mandates within the organization. For this reason, we weight country influence by GDP (logged): the democracy scores of larger countries are more influential in the calculation of the average democracy score within each IO than the democracy scores of smaller members.Footnote 17

If our hypothesis is correct, the resulting variable, % Autocratic Members, should be negatively correlated with the adoption of governance mandates. Even though we are analyzing a set of organizations that are already mostly autocratic, our theory suggests that within this subset of AIOs, homogeneity of regime type will slow the adoption of good governance standards, increase incentives to externalize mandates, and shift to mandates that focus on rule of law issues. There is significant variation in % Autocratic States across IOs, but also within IOs over time. Over IOs and time, on average 84% of IO member states are fully autocratic, but there is significant variation across organizations with some composed fully of autocratic states (i.e., the African Union for much of its existence) and some with much more mixed membership (i.e., the Andean Community with 51% of its members classified as not fully autocratic).

To test whether powerful good governance promoters play a role (Hypothesis 2), we measure external dependence by member states on those promoting good governance standards. We begin with a broad measure of total receipts of overseas development assistance from the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD. We compute the total amount (in millions) of promised aid to all state members of the organization on a yearly basis. We break down our operationalizations of external dependence to official development assistance (ODA) pledged to member states from two different donor sources: the European Union and the United States. While we suspect that both measures (Total US ODA and Total EU ODA) will be positively correlated with adoption of governance standards, past research on democracy governance suggests that the United States has been less demanding of a country’s compliance with these standards (Pevehouse, 2002a), especially when other geopolitical or security issues arise. Thus, we entertain the possibility that there could be differential effects across the two major promoters of good governance standards.

Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Appendix B.

Control variables

We include additional variables in our model to control for possible confounding factors. We are concerned that the number of members in the organization could serve as a predictor of total ODA (more members leading to more aid) but also an inverse predictor of governance mandates (more members leading to fewer mandates due to more difficult majorities). We measure Number of Members as an annual count of the total number of members in the organization. Second, we are concerned that economically wealthier states could more easily resist international pressures to adopt good governance mandates. We therefore control for the sum of gross domestic product (GDP) in the organization (IO GDP).Footnote 18 We use the Penn World Table to measure the real dollar-denominated GDP of each state in the organization each year (Feenstra, Inklaar, and Timmer 2015). Former Colonies is measured as the number of member states that are former colonies. To control for any time-invariant characteristics of regional organizations, we also include AIO fixed effects in the analysis (not reported in the Tables 1 and 2).

Model specification

Given the nature of our data, and the distribution of the dependent variable, we estimate OLS regressions with IO fixed effects to analyze the determinants of the scope of mandate adoption (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Although we present a parsimonious specification for the main analysis, we conducted a number of robustness checks to make sure our results do not depend on these estimation and specification choices. First, we estimate a negative binominal regression model to account for the fact that the dependent variable is a count variable. Second, we also estimate models that include year fixed effects. Finally, we show that the results do not change if we use clustered standard errors. All results are presented in Appendix D.

4 Empirical results

Table 1 presents the results of an OLS estimation with IO fixed effects. We first illustrate our baseline intuition that more homogenously autocratic states are less likely to adopt any type of governance mandate (Model 1).

As shown in Column 1 of Table 1, % Autocratic States is negative and statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. The effect is substantively large. A 1% increase in the number of autocratic states leads to a decline in the scope of mandates by over five mandates. AIOs that have a strong democratic membership (51% of members are autocratic) adopt about four good governance mandates. This drops to less than two good governance mandates for AIOs that are composed almost entirely by autocratic governments. This result provides support for Hypothesis 1 that as autocratic organizations become more dominated by their purely autocratic members, they are less likely to adopt good governance mandates of any kind.

Turning to Hypothesis 2 concerning vulnerability of AIOs to those states pushing good governance standards, the results indicate that ODA provided by the United States has little bearing on the propensity of illiberal IOs to adopt mandates. The correlation between foreign aid from the United States and the scope of good governance mandates is positive, but only marginally significant at the 10% level. Conversely, ODA provided by the European Union is positively correlated with the adoption of mandates, and highly significant. The effect is sizeable: IOs that are not highly dependent on foreign assistance from EU donors adopt on average about two good governance mandates. This increases to over 12 mandates for AIOs where members are highly dependent on aid from European donors. This suggests different responses depending on which state (or group of states) pushes the mandate: AIOs seem to respond to incentives provided by the EU and the United States.

Model 2 evaluates our claim about jurisdiction and the externalization of governance standards. Hypothesis 3 predicts that more homogenously autocratic organizations will be more likely to adopt external governance standards. The estimates of % Autocratic States bear out this idea—more homogenously autocratic organizations adopt external mandates targeted at non-members at a higher rate than those targeted internally. The effect is statistically significant at the 1-percent level.Footnote 19

Turning to the control variables, higher levels of aggregate wealth in an IO is correlated with greater adoption of good governance mandates and a tilt towards internal standards. Larger AIOs are significantly less likely to adopt good governance standards and more likely to externalize any standards they adopt. Former colonies are generally more likely to adopt mandates, but there is no significant difference in their decision to externalize those mandates.

Table 2 presents the results to evaluate Hypothesis 4 regarding mandate substance. Recall that we expect highly autocratic AIOs will be less likely to adopt overtly pro-democracy mandates (versus bureaucracy-related mandates). Model 1 reports our estimates on the effect of autocratic membership on mandates with a focus on democracy promotion, while Model 2 analyzes whether an increase in the percentage of autocracies within AIOs covaries with an increase in bureaucracy-related mandates. As expected, we find that as the share of autocratic members within the AIO increases, the scope of more directly democratic focused mandates decreases. The estimate is significant at the 1% level. Interestingly, AIOs are also less likely to adopt bureaucratic good governance mandates – an estimate that is also statistically significant. Comparing the marginal effects across the two models, however, suggests that AIOs that are more uniformly authoritarian prefer to avoid all good governance mandates, although they appear somewhat more hesitant to adopt democracy-oriented goals. We infer this given that moving from the mean level of % Autocratic States to the maximum value yields a predicted increase that is twice as large for the bureaucratic good governance mandates. Still, the overarching effect is that autocratic IOs appear to be wary of democracy and anti-corruption or rule of law standards. Similarly, we find evidence that more autocratic IOs are significantly more likely to externalize both types of good governance standards. These findings imply that more autocratic IOs avoid and minimize the costs of good mandates altogether when possible.

As we noted throughout the research design portion of the paper, our findings are robust to numerous re-specifications involving changes in measurement, sample, and estimation strategy. Appendix F presents regressions with additional control variables to account for potential omitted variable bias. First, to account for the possibility that underlying preference similarities with the global hegemon could be driving both preferences among AIO members for governance and the success (or failure) of external influence attempts, we compute the average UN voting similarity score with the United States for all AIO members (Bailey et al., 2017). This new control variable (UN Voting, shown in columns 1 and 2 of Appendix F) achieves statistical significance but does not influence the estimates of our variables of interest.

Second, there could be a concern that a potential confounder is the human rights practices of the IO members themselves. It could be that that autocratic states who poorly protect human rights may be accounting for the resistance to democracy governance standards. We therefore introduce a measure of the level of respect for human rights (IO Human Rights) using the latent variable data from Farris (2014) to measure human rights practices at the state level, then take the average across all AIO members in each year. The estimate of this new variable does not achieve statistical significance but more importantly, does not influence the previous estimates of our variables of interest.

Next, we re-estimate a model accounting for a possibility that rather than regime-type, it is a set of domestic preference constraints that influences adoption of governance mandates. To this end, we include the average yearly level of veto players across each state in the AIO (IO Veto Players), introducing this as another potential omitted variable (Henisz and Zelner 2006). As shown in Appendix F, this variable is statistically significant but has no influence on other estimates in the model.

Finally, we are aware of the possibility that membership in AIOs are not random and that country selection into AIOs may also drive preferences about mandates. In an attempt to address this issue, we generate a first-stage model using all country-years in our data to calculate the Mills ratio of the probability that a state joins an autocratic IO in a given year. Within each IO, we then average the member state Mills ratios of joining an autocratic IO. As shown in Appendix H, this has no influence on our independent variables of interest.Footnote 20

Taken together these models provide support for the argument that more homogenously autocratic AIOs are less likely to adopt governance standards, but when they do (largely for reasons of dependence), those standards are more likely to be targeted at non-member states rather than the internal behavior of member states. We find less support for our argument that more autocratic IOs are more likely to avoid mandates that focus on human rights and other issues that are directly related to democracy promotion but are less averse to mandates that address bureaucratic issues associated with good governance such as transparency and corruption. The findings suggest that AIO members avoid good governance mandates indiscriminately, if possible. These autocratic-slanted AIOs are strategic in terms of where they choose to ground the jurisdiction of the good governance mandates they do adopt, but less so in terms of which good governance concepts are acceptable.

5 Conclusions

We addressed the puzzling adoption of good governance standards by many AIOs. We argue that whenever possible, autocratic governments shy away from the adoption of good governance mandates, but their ability to do so depends on the existing winning coalitions within the organization and the AIO’s dependence on powerful external good governance norm providers. AIOs that are composed of mainly autocratic members are less likely to adopt mandates in the first place. If they do, they favor external mandates over mandates that target the internal membership directly. And they tend to eschew standards that are more clearly associated with modern features of democracy promotion and that have written basis in international law.

We analyzed decisions about the adoption of good governance mandates in 48 AIOs between 1945 and 2015. We find that heterogeneity in regime type within AIOs allows some organizations to skirt the sovereignty costs of good governance but foreign dependence can minimize their ability to do so. Interestingly, we find that the United States has been a less effective promoter of good governance mandates in AIOs as opposed to the European Union.

The findings contribute to our understanding of AIOs and the rise of autocracy on the world stage. Whereas existing research has explored the rise and consequences of this new type of IO, or the variation in non-democratic regime types at the national level, our paper highlights the importance of acknowledging that most of these AIOs are composed of members that are very different with respect to regime type. They are heterogeneous. And that is why member preferences toward good governance within these AIOs vary with the composition of the membership and why some AIOs have been more willing to adopt seemingly liberal good governance mandates than others.

By highlighting the variation in sovereignty costs of institutional mandates we further show how members can agree to an adoption of formal norms and rules they might otherwise oppose, all while minimizing the costs of these norms on themselves. In doing so, we underscore the extent to which the spread of good governance norms and talk is not monolithic, certainly not across states and AIOs, but also not across types of mandates. From the perspective of good governance promoters, it may be common to assume that any uptake of such standards is a victory, especially among autocratically inclined IOs. Our work joins a growing body of work that suggests that this might not be the case (Cottiero and Haggard 2023; Ferry et al., 2020; Hafner-Burton and Schneider 2019) and not simply because mandates are cheap talk. They very well may be cheap talk, but that is a question for another paper. Here, we suggest that they may also be used strategically to promote an autocratic agenda—or at least projection of autocratic power—on the world stage through IOs whose member states seek to avoid the uptake of concrete policies for their own democracy promotion in favor of weaker or less well-defined norms of global governance. If good governance promotion can be effective—at least in the uptake of formal rules and rhetoric—the effect is both conditional and strategic.

Notes

We define IOs as democratic if the majority of their membership is democratic, that is, exceed the V-DEM threshold for democracy (0.5), all other IOs are defined as illiberal. Although we use the convention to broadly define the sample of largely authoritarian IOs, we will account for the significant variations within IOs in our analysis. Another common practice is to define IOs as democratic when the average democracy score of the membership exceeds 0.5. Our findings are robust to using this alternative definition. We provide a more in-depth discussion of the conceptualization of AIOs in the research design below.

Furthermore, our main results are consistent with the view that autocratic IO members consider the adoption of good governance mandates as potentially costly. AIOs are less likely to adopt good governance mandates (and more likely to externalize those mandates) when their membership is more autocratic and they can assert themselves in the decision-making process against members that might be more favorable to adopting good governance mandates.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/good-governance/about-good-governance, last accessed: October 18, 2022.

Similar arguments have been made with respect to investor risk (Gray, 2013).

ECOWAS includes Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

https://au.int/en/newsevents/20191007/3rd-edition-african-anti-corruption-dialogue, last accessed: October 18, 2022.

https://papsrepository.africa-union.org/xmlui/handle/123456789/559, last accessed: October 18, 2022.

A list of IOs with their abbreviations can be found in Appendix A.

Appendix G presents results that include all 76 organizations in the sample.

We generated the same measure using V-Dem’s liberal democracy index. The results, which are robust, are presented in Appendix C.

We tested for the robustness of the results to using slightly different thresholds (0.4 and 0.6). The results are presented in Appendix G. Another way to conceptualize AIOs is to use the average democracy score of IO members, whereby an IO would be defined as autocratic if the average democracy score of its membership is below 0.5. As presented in Appendix G, our results are robust to using this way of conceptualizing AIOs.

We were concerned that the results may be driven by African IOs, which present a plurality of organizations in our sample of AIOs. In Appendix E, we estimate our regressions on a sample without African AIOs and a sample that only includes African AIOs. The results are consistent.

In Appendix C, we demonstrate that the results are robust to using the average autocracy score within an AIO.

We present regressions with unweighted scores in Appendix C.

Using the average of per capita GDP yields very similar results to those discussed.

The mean of the dependent variable is negative, suggesting that internal mandates are generally more common than external ones. The positive coefficient implies a move towards a balance of external mandates over internal ones as predicted by Hypothesis 3.

Our first-stage probit model includes region fixed -effects and the V-DEM polyarchy score of the country under observation. We are aware that this evidence as limited in at least two ways. It does not control for any unobservable country-level characteristics which could lead to joining an AIO and resisting governance provisions and it averages country-level propensities to join AIOs across all members (which is needed given that our unit of analysis is the RIO).

References

Abbott, K. W. (2000). Hard and Soft Law in International Governance. International Organization,54(3), 421–456. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551280

Alter, K., Helfer, L., & McAllister, J. (2013). A New International Human Rights Court for West Africa: The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice. American Journal of International Law,107, 737–779.

Avoulete, K. (2022). Should ECOWAS Rethink Its Approach to Coups? - Foreign Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/article/2022/02/should-ecowas-rethink-its-approach-to-coups/ (October 18, 2022).

Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 430–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200271559

Barnett, M. N., Pevehouse, J. C. W., & Raustiala, K. (2021). Global governance in a World of Change. Cambridge University Press.

Börzel, T. A., Pamuk, Y., & Stahn, A. (2008). Good Governance in the European Union. Berlin Working Paper on European Integration No. 7. Centre for European Integration of the Otto Suhr Institute for Political Science at the Freie Universität Berlin. Available at https://www.fu-berlin.de/europa.

Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2009). The transformative power of Europe: The European Union and the diffusion of ideas. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, FB Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften, Otto-Suhr-Institut für Politikwissenschaft Kolleg-Forschergruppe “The Transformative Power of Europe.” https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-364733

Bueno de Mesquita, B. & Smith, A. (2009). A Political Economy of Aid. International Organization,63(2), 309–340.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R. M., & Morrow, J. D. (2003). The logic of political survival. MIT Press.

Carbone, M. (2012). The European Union, Good Governance and Aid Co-ordination. In EU strategies on Governance Reform. Routledge.

Checkel, J. T. (1999). Norms, institutions, and National Identity in Contemporary Europe. International Studies Quarterly,43(1), 83–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00112

Checkel, J. T. (2001). Why comply? Social Learning and European Identity Change. International Organization,55(3), 553–588. https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180152507551

Cole, W. M. (2005). Sovereignty Relinquished? Explaining commitment to the International Human rights covenants, 1966–1999. American Sociological Review,70(3), 472–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000306

Coppedge, M., Gerring, Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., et al. (2022). V-Dem codebook V12 varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project. https://www.v-dem.net/documents/1/codebookv12.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2024

Cottiero, C. (2021). Staying Alive: Regional Integration organizations and vulnerable leaders. Book Manuscript.

Cottiero, C., & Haggard, S. (2023). Stabilizing authoritarian rule: The role of International Organizations. International Studies Quarterly,67(2), sqad031. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqad031

Debre, M. J. (2021a). Clubs of autocrats: Regional organizations and authoritarian survival. The Review of International Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09428-y

Debre, M. J. (2021b). The Dark side of Regionalism: How Regional Organizations Help authoritarian regimes to Boost Survival. Democratization,28(2), 394–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1823970

Elliott, K. A. (Eds.). (1997). Corruption and the Global Economy. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Fariss, C. J. (2014). Respect for Human rights has Improved Over Time: Modeling the changing Standard of accountability. American Political Science Review,108(2), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000070

Feenstra, R. C., & Inklaar, R. (2015). The Next Generation of the Penn World table. American Economic Review,105(10), 3150–3182. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130954

Ferry, L. L., Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Schneider, C. J. (2020). Catch me if you care: International Development Organizations and National Corruption. The Review of International Organizations,15(4), 767–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09371-z

Finnemore, M. (1993). International Organizations as teachers of norms: The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization and Science Policy. International Organization,47(4), 565–597. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300028101

Finnemore, M. (1996). Norms, Culture, and World politics: Insights from sociology’s institutionalism. International Organization,50(2), 325–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300028587

Gray, J. (2009). International Organization as a seal of approval: European Union Accession and Investor Risk. American Journal of Political Science,53(4), 931–949.

Gray, J. (2013). The Company States keep: International Economic organizations and Investor perceptions. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139344418

Gray, J. (2018). Life, death, or Zombie? The Vitality of International Organizations. International Studies Quarterly,62(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx086

Greenhill, B. (2015). Transmitting rights: International organizations and the diffusion of Human rights practices. Oxford University Press.

Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2005). Trading Human rights: How preferential Trade agreements influence government repression. International Organization,59(3), 593–629. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050216

Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2009). The Power politics of Regime Complexity: Human rights Trade conditionality in Europe. Perspectives on Politics,7(1), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709090057

Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2012). International regimes for Human rights. Annual Review of Political Science,15(1), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-031710-114414

Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2013). Making Human rights a reality. Making Human rights a reality: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400846283

Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Christina, J. S. (2019). The Dark side of Cooperation: International organizations and Member Corruption. International Studies Quarterly,63(4), 1108–1121. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz064

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Hyde, S. D., & Jablonski, R. S. (2014). When do governments Resort to Election Violence? British Journal of Political Science,44(1), 149–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000671

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Hyde, S. D., & Jablonski, R. S. (2018). Surviving elections: Election Violence, Incumbent Victory and Post-election repercussions. British Journal of Political Science,48(2), 459–488. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712341600020X

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2023). Rhetoric and Reality: International Organizations, Sovereignty Costs, and Human Rights. Working paper, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2015). Human rights Institutions, Sovereignty costs and democratization. British Journal of Political Science,45(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000240

Haftel, Y. Z. (2007). Designing for Peace: Regional Integration arrangements, institutional variation, and Militarized Interstate disputes. International Organization,61(1), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070063

Hathaway, O. A. (2007). Why do countries commit to Human rights Treaties? Journal of Conflict Resolution,51(4), 588–621. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707303046

Henisz, W. J., & Zelner, B. A. (2006). Interest groups, veto points, and electricity infrastructure deployment. International Organization, 60(1), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818306060085

Hollyer, J. R., & Wantchekon, L. (2015). Corruption and ideology in autocracies. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 31(3), 499–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewu015

Kelley, J. (2004). International actors on the domestic scene: Membership conditionality and socialization by International Institutions. International Organization,58(3), 425–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818304583017

Keping, Y. (2018). Governance and good governance: A New Framework for Political Analysis. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences,11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-017-0197-4

King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2013). How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. American Political Science Review,107(2), 326–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014

Kuziemko, I. (2006). How much is a seat on the Security Council Worth? Foreign Aid and Bribery at the United Nations. Journal of Political Economy,14(5), 905–930.

Lupu, Y. (2015). Legislative veto players and the effects of International Human rights agreements. American Journal of Political Science,59(3), 578–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12178

Mansfield, E. D. (2008). Democratization and the varieties of International Organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution,52(2), 269–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707313691

Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2006). Democratization and International Organizations. International Organization,60(1), 137–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830606005X

Moravcsik, A. (2000). The origins of Human rights regimes: Democratic Delegation in Postwar Europe. International Organization,54(2), 217–252. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551163

Nagar, D., & Nganje, F. (2016). The AU’s Relations with the United Nations, the European Union, and China. Centre for Conflict Resolution. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05178.13 (October 18, 2022).

Neumayer, E. (2005). Do International Human rights Treaties improve respect for Human rights? Journal of Conflict Resolution,49(6), 925–953. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002705281667

Obydenkova, A. V., & Libman, A. (2019). Authoritarian regionalism in the World of International Organizations: Global perspective and the eurasian Enigma. Oxford University Press.

Panke, D., Stapel, S., & Starkmann, A. (2020). Comparing Regional organizations: Global Dynamics and Regional particularities. Bristol University.

Pevehouse, J. C. (2002a). Democracy from the Outside-In? International Organizations and democratization. International Organization,56(3), 515–549. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081802760199872

Pevehouse, J. C. (2002b). With a little help from my friends? Regional organizations and the consolidation of democracy. American Journal of Political Science,46(3), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088403

Pevehouse, J. C. (2005). Democracy from above: Regional organizations and democratization. Cambridge University Press.

Poast, P. (2015). How International Organizations Support democratization: Preventing authoritarian reversals or promoting consolidation? World Politics,67(1), 72–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887114000343

Poast, P., & Urpelainen, J. (2018). Organizing Democracy: How International Organizations assist New democracies. University of Chicago Press.

Schimmelfennig, F. (2008). EU Political Accession Conditionality after the 2004 enlargement: Consistency and effectiveness. Journal of European Public Policy,15(6), 918–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802196861

Schneider, C. J. (2007). Enlargement processes and distributional conflicts: The politics of discriminatory membership in the European Union. Public Choice,132(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-006-9135-8

Schneider, C. J. (2009). Conflict, negotiation and European Union Enlargement. Cambridge University Press.

Schneider, C. J., & Tobin, J. L. (2013). Interest coalitions and Multilateral Aid Allocation in the European Union. International Studies Quarterly,57(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12062

Schneider, C. J., & Urpelainen, J. (2013). Distributional conflict between powerful States and International Treaty Ratification. International Studies Quarterly,57(1), 13–27.

Stapel, S. (2022). Regional organizations and Democracy, Human rights, and the rule of Law: The African Union, Organization of American States, and the diffusion of institutions. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90398-5

Stout, B. (2020). It’s Africa’s Turn to Leave the European Union. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/10/african-union-european-union-trade/ (October 18, 2022).

Tansey, O. (2016). The International politics of authoritarian rule. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199683628.001.0001

TNI. (2000). Relations between Africa and the European Union in the 21st Century. Transnational Institute. https://www.tni.org/es/node/14690. Accessed 24 Mar 2024

United Nations. (1998). United Nations `Indispensable Instrument’ for Achieving Common Goals, Says Secretary-General In Report to General Assembly. UN Press Release SG/2048 GA/9443.