Abstract

International donors emphasize greater recipient-country ownership in the delivery of foreign assistance because it ostensibly promotes the efficient use of resources and strengthens recipient-country administrative capacity. The preferences of citizens in developing countries, however, are not well understood on this matter. Do they prefer that their own governments control foreign aid resources, or are there conditions under which they instead prefer that donors maintain control over how aid is implemented? We explore these questions through parallel survey experiments in Myanmar, Nepal, and Indonesia. Our experimental vignettes include two informational treatments: one about who implements aid (i.e., the donor or the recipient government) and the other about the trustworthiness of the foreign donor. The trust-in-donor treatment, on average, increases levels of support for aid in all three countries. In contrast, we observe heterogenous average treatment effects regarding aid control: control of aid by the donor rather than the government reduces levels of support in Indonesia and Myanmar, whereas it increases support levels in Nepal. We show how the cross-country variation in ATEs originates in consistent individual-level variation in reactions to aid control that is more shaped by respondents’ trust in their own government than their trust in the donor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the early 2000s, donor governments and international organizations announced their commitment to incorporating greater country ownership into the delivery of foreign assistance. The principle of ownership, defined as countries having “more say over their development processes…and more use of country systems for aid delivery,” was codified in the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the 2008 Accra Agenda for Action.Footnote 1 In accordance with this definition, transferring control over how aid should be used and implemented to aid-receiving governments has since been considered critical for economic development because of the potential for domestic ownership to promote efficacy and strengthen domestic administrative capacity.Footnote 2

Despite the claimed superiority of recipient-country ownership, whether or not citizens in developing countries themselves welcome the arrangement is not well understood. On the one hand, we can imagine citizens instinctually agreeing with the ideas enumerated in the international community’s agenda, preferring that already existing local administrative institutions oversee aid-financed projects. Additionally, citizens in aid-receiving countries may recognize their country’s need for aid but may not trust foreign donors’ motives, and this might be another reason to prefer domestic government control. On the other hand, we can imagine citizens thinking that international actors are better suited to bring about development success, suspecting that leaders and officials of their own governments lack the competence and probity to implement projects in a manner that would benefit the public rather than private interests.

Do citizens in aid-receiving countries truly prefer that their own governments control foreign aid resources? Or are there conditions under which they instead wish that donors would maintain control over how aid is used and implemented? To date, research on the views of aid-recipient publics regarding who should control aid projects is scarce. A set of related studies that focus on Uganda report citizens to be more supportive of donor-funded, as compared to government-funded, projects (Findley et al., 2017a, b; Milner et al., 2016). Another piece of research, also from Uganda, finds that an overwhelming majority of survey respondents would rather have foreign aid donors give money to NGOs than to district governments (Baldwin & Winters, 2020). These studies thus provide evidence that average citizens in at least one aid-receiving country may not be as enthusiastic about the principle of country ownership as members of the international community.Footnote 3 It is difficult to gauge, however, the extent to which these findings are generalizable in the absence of data from other cases.

We seek to advance the literature in two ways. First, we propose a simple but general argument about the determinants of citizens’ preference for donor control versus government control over aid resources. This preference, we argue, depends on the extent to which aid-recipient publics trust foreign donors and their own governments respectively. We expect the perceived trustworthiness of these actors to vary within and across countries, and we expect preferences over which actor should control aid to differ accordingly. Second, we extend the horizon of empirical inquiry by conducting parallel survey experiments in three countries in Asia where questions about preferences over aid have not yet been asked: Myanmar, Nepal, and Indonesia. These three countries are well suited for our task. On the one hand, these countries share common characteristics: they all receive foreign aid from multiple donors; the concept of foreign aid is thus familiar to their mass publics; and at the time of our surveys, they were all nominal democracies where public opinion could have some influence over policy.Footnote 4 On the other hand, the three countries differ in their level of dependence on foreign aid as well as their relations with foreign donors. This contextual diversity should allow us to determine whether the individual-level dynamics that we posit generalize to countries with these different characteristics.

We designed experimental vignettes that included two informational treatments: one about who implements the aid (i.e., the donor or the recipient government) and the other about the trustworthiness of the donor. Pre-treatment, we also collect data on respondents’ trust in their own government. When pooling our data across the three countries, we find that support for aid generally increases when the aid is provided by a trustworthy donor (1.26-point difference on a 10-point scale; p < 0.001) but that the average treatment effect (ATE) for donor (as opposed to government) control is -0.20 points on a 10-point scale (p < 0.05). As we highlight below, however, this ATE for control over aid masks substantial heterogeneity across individuals in the samples. Overall, we find that whether or not aid-recipient publics prefer that aid be controlled by the donor depends, first, on how much they trust their own government and, second, on whether the donor is trustworthy. Following the presentation of the results, we discuss why we expect these findings to be transportable to a broad range of aid-receiving countries.

Understanding when publics in recipient countries will support the provision of different kinds of aid projects is crucial for a number of reasons. First, it has implications for the efficacy of aid in terms of development impact. Research shows that involving potential aid beneficiaries at different stages of aid interventions can enhance projects’ outcomes, although this is not always the case (Wong, 2012). Information on recipient public’s views is also important for donors’ public diplomacy goals. Unfavorable views of aid provision could result in negative images of donors that generalize to other aspects of donors’ interactions with aid-receiving countries (Goldsmith et al., 2014). Finally, paying more attention to public opinion in aid-receiving countries can be seen as a step forward in the “participation revolution”—the call to “include people receiving aid in making the decisions which affect their lives,”Footnote 5 which was enshrined in the 2016 “Grand Bargain,” an agreement between the largest donor countries, multilateral organizations, and international NGOs (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2016). Knowing how the public in recipient countries regards aid may help donors either justify or else amend current practices.

2 Trust and Attitudes Toward Foreign Aid

Before the end of the Cold War, it was not uncommon for leaders in the developing world to express outright mistrust of donor countries. For example, in his address to the U.N. General Assembly in 1984, President Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso declared:

Of course, we encourage aid that aids us in doing away with aid. But in general, welfare and aid policies have only ended up disorganizing us, subjugating us and robbing us of a sense of responsibility for our own economic, political and cultural affairs (cited in Nyikadzino, 2021).

Even today, this sentiment resonates around the world. Scholars publish research and journalists write editorials that point to and condemn donor countries for seemingly ineffective or even harmful aid programs (e.g., Moyo, 2009; Langan & Scott, 2011; Jayawickrama, 2018; Foster, 2021). In the early 2000s, this type of criticism prompted bilateral and multilateral organizations to express their commitment to incorporating greater country ownership into the delivery of foreign assistance.

What lies behind the persistent skepticism of donors? The empirical literature on aid allocation provides some insight, as it emphasizes that aid often serves donors’ interests rather than recipient countries’ welfare. Indeed, at the aggregate level, a number of studies show that foreign aid is often allocated for geopolitical or commercial reasons rather than in response to recipient-country need (e.g., Schraeder et al., 1998; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith, 2007, 2009). At a more micro-level, however, whether and/or the extent to which individual citizens of aid-receiving countries perceive donors as self-seeking is not yet well documented. If a perception of donors as self-interested is widely shared, citizens may not be supportive of foreign aid projects, especially those controlled by donors. On the other hand, if citizens are especially skeptical of the intentions or capabilities of their own government, then they may be particularly supportive of foreign-funded development projects.

To be sure, research on aid-receiving publics’ attitudes toward foreign aid is growing, but only a few studies directly focus on citizens’ preferences regarding who should control foreign aid implementation. In survey experiments conducted in Uganda, one group of authors finds that citizens prefer donor control to government control (Findley et al., 2017a, b; Milner et al., 2016). These studies suggest that skepticism of donors may be more of an elite phenomenon than a general attitude among ordinary citizens, as they report that members of parliament—in contrast to the mass public—prefer government projects to donor-controlled projects. A different study from Uganda also finds that three-quarters of survey respondents would rather have foreign aid donors give money to NGOs than to district governments (Baldwin & Winters, 2020). Finally, a study using Afrobarometer data and data from Kenya finds strikingly high levels of support for donor conditionality among publics in aid-receiving countries (Clark et al., 2023). Thus, the limited literature yields empirical evidence at odds with the principle of country ownership upheld by the international community.

What further complicates understanding citizens’ evaluations of aid is the fact that, in recent years, the list of donor countries and organizations has diversified, and donors’ intentions—claimed and revealed—now seem more heterogeneous than before. Given the variety of dyadic relationships between donors and recipients, it is not surprising that evaluations of particular donors do not always converge into uniform conclusions. Take, for example, the contrasting remarks made by different political elites regarding China as a donor. On some occasions, China’s aid practices are highly praised, as in the following statement by Senegal’s President Abdoulaye Wade in 2008: “China’s approach to our needs is simply better adapted than the slow and sometimes patronising post-colonial approach of European investors, donor organisations and non-governmental organisations.”Footnote 6 In other instances, Chinese intentions are not well received; for example, a Municipal Council member in Sri Lanka compared a major development project financed with Chinese aid to the Japanese-funded Colombo port: “Everyone understands Japan’s assistance has contributed to the development of our nation. In contrast, I regret that Chinese assistance seems harmful.”Footnote 7

There is no reason to presume only political elites distinguish between specific donors; ordinary citizens are also likely to suspect that different donor countries and organizations may have different purposes and strategies. We argue that an important criterion for citizens’ evaluations of aid is the extent to which they trust a particular donor, especially in terms of the latter’s intention to promote the welfare of the aid-receiving country rather than its own interests.

We understand trust as a “subjective judgment that [one party] makes about the likelihood of [another party] following through with an expected and valued action under conditions of uncertainty” (Jackson & Gau, 2016, 53). In the realm of international development assistance, the “expected and valued action” is the donor providing financing, as well as structures around that financing, that yield benefits and prevent harms to local citizens and/or the national economy as a whole.

Ceteris paribus, citizens are more likely to be supportive of aid provided by trusted donors than that provided by untrusted donors. Further, on the choice of who should control aid implementation, citizens’ preference for donor versus government control must be contingent, at least in part, on the degree to which they trust the donor in question. That is, citizens are more likely to prefer donor control as opposed to government control, when they perceive the donor to be trustworthy for administering aid projects in a manner that brings about general benefits to their country.

Despite the recognized importance of trust in other aspects of international cooperation (Deutsch et al., 1957; Fukuyama, 1995; Hoffman, 2002; Kydd, 2000, 2007), the literature on how trust affects aid relations is less developed. Several studies explore how the perceived trustworthiness of recipient countries, in the eyes of donors, affects their aid delivery (Clist et al., 2012; Dietrich, 2011; Knack, 2013, 2014; Molenaers et al., 2017; Winters, 2010). Most research on attitudes toward aid in developing countries has not focused explicitly on the influence of trust in donors. The series of studies on Uganda cited above (Findley et al., 2017a, b; Milner et al., 2016) finds that Ugandans do not distinguish between various donors when assessing the desirability of aid projects, suggesting that they may trust donors equally. A study of Ukrainian attitudes toward aid suggests that background perceptions of donors’ motives matter: the authors find that manipulation of donor intentions influenced Ukrainians’ support for aid from the EU but not from Russia (Alrababa’h et al., 2020). Clark et al. (2023) find that Kenyans who view the influence of a particular foreign country as generally positive support higher levels of conditionality attached to aid coming from that donor.

Even within the same recipient country, citizens are unlikely to have uniform perceptions about particular donor countries. It is possible, for example, that some segment of citizens in a given aid-receiving country may view the United States as a trusted donor in the sense that it pursues what is best for the aid-receiving country, but other segments of citizens may perceive the United States as a distrusted donor. Some perceptions about a particular donor may be more stable than others, and they may be so only for some citizens and in some contexts. Furthermore, citizens are unlikely to have uniform perceptions of how aid should be used. As shown in the study on Ukraine (Alrababa’h et al., 2020), some citizens in aid-receiving countries may believe that aid provided to gain power and influence over them is what is best for their country in the moment, while other citizens may prefer aid intended for alternate purposes.

We turn next to a discussion of citizens’ trust in their own governments. Parallel to our understanding of trust in donors above, trust in the government revolves around a belief that the government will pursue development policies beneficial for local citizens and/or the national economy as a whole. Just as support for aid is a function of trust in donors, citizens’ attitudes must also be influenced by how much they trust their own government to deliver and administer aid in ways that benefit their country (see also Clark et al., 2023). It is widely documented that many developing-country governments misuse aid resources. Aid has been shown, for example, to prolong authoritarian rule (Bueno de Mesquita and Smith, 2009; Kono & Montinola, 2009; Licht, 2010),Footnote 8 to fuel corruption (Bräutigam & Knack, 2004; Svensson, 2000),Footnote 9 and to be captured by elites (Andersen et al., 2022).

Just like trust in donors, trust in government is likely to vary from one individual to another for various reasons, including but not limited to political partisanship and socioeconomic background. More to the point, citizens may not trust their government if they perceive that the latter often uses aid for its own interests rather than the public good. Citizens who do not trust their government may thus be less supportive of aid than those who have more favorable views of their government, especially if the aid is controlled by their government. For these individuals, donor control over the implementation of aid projects may be preferable to government control, regardless of the extent to which they trust the donors and their intentions.

In sum, the question as to whether citizens would agree with the principle of country ownership over aid becomes a matter of trust in the donor as well as trust in their own government. Based on the discussion above, we derive the following hypotheses:

-

H1: Support for aid from a trusted donor will be higher than support for aid from an untrusted donor.

-

H2: Support for donor-controlled aid will be higher if the aid is from a trusted donor, as opposed to an untrusted donor.

-

H3: Support for aid will be higher among individuals with high trust in government, as compared to among individuals with low trust in government.

-

H4: Support for donor-controlled aid will be higher among individuals with low trust in government, as compared to among individuals with high trust in government.

3 Survey Experimental Design

3.1 Case Selection

To test our hypotheses, we fielded information experiments using computer-assisted face-to-face surveys in Myanmar, Nepal and Indonesia, as resource constraints limited us to selecting three countries in Asia for this research. We selected these countries for the following reasons: they receive foreign aid from multiple donors, and the concept of foreign aid should thus be familiar to their mass publics; in addition, in these countries, public opinion played a role in government decisions at the time of our experiments.Footnote 10

Despite these underlying similarities across the cases, the three countries differ in their experience with, and financial dependence on, foreign aid. Specifically, Nepal is a longtime recipient of relatively high levels of aid, making it most similar among the three to Uganda, which had been the central focus of relevant previous studies. Indonesia, on the other hand, has received relatively low levels of foreign aid since the 1970s. Myanmar, while its engagement with donors has fluctuated over the decades, was subject to stringent donor sanctions from 1988–2016.Footnote 11 In light of this diversity, we intuit that observing similar individual-level dynamics across these countries will give us more confidence that such dynamics are likely to hold across a wide range of countries.

3.2 Sampling

The Myanmar survey was conducted in January and February 2019, two years before the military coup that removed the National League for Democracy (NLD) government from power. The surveys in Nepal and Indonesia were conducted between November 2019 and January 2020. In each country, the sample size was roughly one thousand, and respondents were selected randomly from the population of the largest city, namely Yangon, Kathmandu and Jakarta. While our decision to concentrate on each country’s largest city was driven primarily by resource limitations, we note that citizens in these cities will have various opinions on many social, economic, and political issues and therefore are likely to have different attitudes toward their domestic governments and toward foreign aid. We tried to capture this diversity of attitudes by drawing a representative sample of respondents in terms of age (18 and above), gender, and socio-economic classification (SEC); the specific measurement of SEC used in each country was different (see Section A1 in the Supplementary Information (SI) for the details of our sampling procedure). Aware of the limits of our samples, after reporting our main results, we conduct analyses to determine the extent to which our city-based results would generalize to other regions in each country as well as to other countries. We discuss these issues in a section on the external validity of our research below.

3.3 Treatment

Our experimental design was a two-factor, between-participants design with four conditions. First, for our trust-in-donor treatment, we randomly assigned respondents to two groups, one in which respondents were instructed to think of an aid-providing country that they trust to do what is best for [their country] and the other in which respondents were instructed to think of an aid-providing country that they do not trust to do what is best for [their country]. Second, for our control-of-aid treatment, we randomly assigned respondents to two groups, one in which the respondents were told that the aid was going to be controlled by the aid-providing country and the other in which the respondents were told that the aid was going to be controlled by their own government. The wording for the vignette was originally written in English and then translated into each local language.

Each vignette began with a common introductory paragraph:

As you may know, our country each year receives substantial financial aid from other countries. In the past, foreign aid has helped with the construction of bridges, health clinics and schools as well as with improvements to our standard of living more generally.

This paragraph was followed by one of two versions of the trust-in-donor treatment, specified as below (using the example of the Indonesia survey):

Trusted Donor

Please think of a foreign country that you trust to do what is best for Indonesia. Suppose this country, that you trust, is offering to provide us a new aid package for the next several years.

Untrusted Donor

Please think of a foreign country that you do not trust to do what is best for Indonesia. Suppose this country, that you do not trust, is offering to provide us a new aid package for the next several years.

The next paragraph included one of two versions of our control-of-aid treatmentFootnote 12:

Donor Control

This money will not become part of our national government budget. {Trusted Donor/ Untrusted Donor}, therefore, will have primary responsibility for administering the aid projects. Our national leaders will not be involved in making key decisions over how this money is used.

Government Control

This money will become part of our national government budget. Our national leaders, therefore, will have primary responsibility for administering the aid projects. {Trusted Donor/Untrusted Donor} will not be involved in making key decisions over how this money is used.

In {Trusted Donor/Untrusted Donor} above, the phrase “This foreign country that you trust” was inserted for those respondents assigned to the Trusted-Donor condition. Alternatively, the phrase “This foreign country that you do not trust” was inserted for those respondents assigned to the Untrusted-Donor condition. For balance checks of treatment assignment, see Tables A1 and A2 in the SI.

The manipulation of trust here is in line with our definition above: we ask respondents to think of a foreign country that will do “what is best” for their own country. By referring to a generic class of countries – those that the recipient either does or does not trust – we avoid information equivalence problems that can arise when using the names of specific countries (Brutger et al., 2022; Dafoe et al., 2018). That is, rather than providing specific donor names (e.g., “China,” “Japan”), seeing how results differ across those treatments, and then trying to make inferences about the characteristics of the countries that drive any observed differences (e.g., “people trust Japan, while they do not trust China”), we instead directly treat respondents with the donor characteristic of theoretical interest.

In our survey, after collecting responses on the outcome variable (described in the next section), we asked respondents to tell us which donor country they were thinking about in response to the stimulus. It is noteworthy that the vast majority of respondents across the three countries were able to name a donor that they trusted or did not trust (in accordance with the treatment they received). In Indonesia, only one percent of respondents were unable to name a donor. In Myanmar and Nepal, these values were higher, but still relatively small—12 percent in the former, and 8 percent in the latter. More importantly, as shown in Table 1, respondents in each sample thought about a variety of different countries (and even some international organizations) when asked to think about a donor that they either did or did not trust and that, within any of the three samples, there tended to be respondents who both did and did not trust the same donors. For instance, 32 percent of Indonesian respondents assigned to the untrusted donor condition named China as the untrusted country, while 25 percent of Indonesian respondents assigned to the trusted donor condition named China as the trusted country about which they were thinking. This variation in responses validates our decision to avoid the use of specific donor names and instead directly employ the concept of interest in our experimental stimuli.Footnote 13

3.4 Outcome Variable

Our key outcome variable of interest is the individual level of support for the new package of foreign aid. Specifically, we measure this with the following question:

We would like to know the overall level of your support for this new aid package. Once again, to remind you, {Trusted Donor/Untrusted Donor} is offering to provide a new aid package for the next several years, and {Donor Control/Government Control}. Given this situation, how enthusiastic do you feel about this aid? Please indicate your level of enthusiasm on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means that you do not at all welcome this aid package and 10 means that you welcome this aid package very enthusiastically.

In the above, for {Donor Control/Government Control}, the whole paragraph of either the donor control treatment or the government control treatment was inserted contingent on the respondent’s group assignment.

4 Results

In this section, we first provide the average treatment effect estimates for the two experimental treatments, finding that there is higher support for aid from trusted donors (in line with H1) but mixed reactions, on average, to the donor-control treatment. When we analyze the interaction between the two treatments, the evidence runs counter to H2: there is not much support for the idea that trust in the donor drives reactions to donor control of aid. After a discussion of how trust in government varies across the three cases, we then show, in line with H3, that trust in government correlates strongly with support for aid. And finally we show that support for donor-controlled aid is highest among individuals who have the lowest levels of trust in government, a pattern consistent with H4 and one that helps explain the inconsistent average treatment effects for the donor-control treatment. This conditional effect – where only individuals low in trust in government support donor control of aid – is our most important finding.

In our first hypothesis, we propose that respondents will express more support for aid when it comes from a trusted donor as compared to when the aid comes from an untrusted donor. Table 2 presents the means and 95% confidence intervals of respondents’ level of enthusiasm for aid by donor type (untrusted and trusted) and by country; the differences in means reflect the unconditional effects of our trust-in-donor treatment on respondents’ support for aid (see also Figure A1 in the SI). We also report the results derived from pooling data from all three countries together. Note that, in each country, a large proportion of respondents expressed some enthusiasm for aid even when they do not trust the donor (indicating that they prefer receiving aid from an untrusted donor to receiving no aid at all). When asked to rate their support for aid from an untrusted donor, fifty percent of respondents in Indonesia chose 7 or higher on a scale from 1–10. The median response for respondents from Nepal and Myanmar is lower at 6 and 5 respectively, but still above the midpoint of the scale.

Despite the high levels of support for aid that we see in the not-trusted-donor condition, the patterns with regard to the effect of the trust-in-donor treatment nonetheless uniformly meet our expectations stated in H1. The estimated effects are all in the expected direction and statistically significant at conventional levels, although the magnitude of the ATEs varies substantially across the three countries, ranging from a very small effect of 0.28 (on a 10-point scale) in Indonesia, a 0.16 standard deviation increase in the level of support for aid, to a quite substantial 2.95-point effect in Myanmar, a 1.02 standard deviation increase. Remarkably, the treatment drove respondents in Myanmar from the lowest mean value of support across the three countries in the untrusted donor condition to the highest mean value of support across the three countries in the trust condition.Footnote 14 The substantial variation in ATEs across the three cases indicates that “trust” cues move some people more than others.

We next proceed to the question of how respondents feel about donor control of aid. Table 3 shows ATEs for the control-of-aid treatment (see also Figure A2 in the SI). Overall, as illustrated in the pooled results, respondents assigned to the condition where the aid is said to be controlled by the government tend to support the aid package more than those assigned to the condition where the donor is said to have primary responsibility for administering the aid project. However, the effects of the control-of-aid treatment are not uniform across the three countries. In Indonesia and Myanmar, respondents, on average, prefer that the forthcoming aid be controlled by their own government rather than the donor (the ATEs of control by the donor in Indonesia and Myanmar, respectively, are 0.19 and 0.25 standard deviation decreases in the level of support for aid). Results from Nepal point in the opposite direction: respondents are more enthusiastic when aid is said to be controlled by the donor than their own government (the ATE is a 0.17 standard deviation increase). The results for Indonesia and Myanmar run contrary to the research cited above, while those from Nepal are consistent with it (Clark et al., 2023; Findley et al., 2017a, b; Milner et al., 2016).

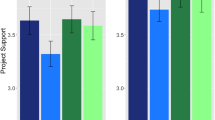

We turn next to H2-whether the trust-in-donor treatment conditions preferences regarding who should control aid. We regress our outcome variable of interest (support for the new aid package) on both treatments and their interaction. As shown in Table 4, results with respect to H2 are mixed across the three countries. The coefficients on the interactions between the trust-in-donor and control-of-aid treatments are all positive, suggesting that support for donor-controlled aid increases when respondents think about a donor that they trust; the results are statistically significant, however, only for Myanmar. More importantly, calculating the marginal effects of the control-of-aid treatment conditional on the trust-in-donor treatment, the empirical pattern shown in Table 3 holds: regardless of their level of trust in the donor, respondents in Nepal tend to prefer donor-controlled aid, whereas those in Indonesia and Myanmar tend to oppose aid controlled by the donor (see Fig. 1). This suggests that it is not trust in the donor that primarily drives preferences regarding which actor controls aid.

We have thus far analyzed the impact of the randomly assigned treatments regarding donor type (trusted versus untrusted) and control over aid (donor control versus aid-receiving-government control). However, as we hypothesize (H3), citizens’ enthusiasm toward aid is also likely to be influenced by their perceptions of the trustworthiness of their own government. Ceteris paribus, citizens are most likely to be enthusiastic about a new aid package when they fully trust the current government to act in the interest of the general public. Furthermore, citizens’ evaluations of the government’s trustworthiness may interact with, and thus condition, their preferred choice between government- and donor-controlled aid (H4).

In our surveys, we measured levels of trust in government with the following question (using the example of the Indonesia survey):

We are interested in how you think about different institutions. For each institution which I am going to name, could you tell us on a scale from 1 to 10 how much trust you have in that institution to act in the interest of the general public in Indonesia, where 10 means that you completely trust the institution to act in the interest of the general public and 1 means that you do not at all trust the institution to act in the interest of the general public.

Among the institutions listed was “Our national government.”

Figure 2 shows that patterns of trust in government differ considerably across the samples from the three different countries.Footnote 15 The median value on a 10-point scale is highest in Myanmar at 9, also high in Indonesia at 8, and much lower in Nepal at 5.Footnote 16

To identify more systematically both the direct and moderating effects of perceived trustworthiness of government, we run OLS models. Since the trust in government variable was not experimentally manipulated, we include in the models covariates that might be correlated with both trust in government and support for aid. They consist of standard demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, and income), as well as variables measuring respondents’ nationalistic tendencies, perceptions of their country’s aid dependence, and their level of trust in international organizations. While these variables may be associated with trust in government, they may also have an independent effect on support for aid. One can imagine, for example, someone who strongly identifies with the nation-state having preferences about aid independent of their preferences regarding the current government. The same can be argued of respondents’ perception of their country’s aid dependence and trust in international organizations, although here the link between such perceptions and trust in government may be closer, as respondents’ may blame the government for their country’s need for aid from international organizations.Footnote 17 The survey questions for these covariates as well as the measure of trust in government all preceded the experimental manipulations. See Section A2 in the SI for more details about these variables.

Results for the direct effects of trust in government on support for the new aid package (H3) are shown in Table 5. Conditional on the other individual-level background covariates, we see a positive and significant correlation between trust in the domestic government and support for aid: individuals who trust their own government more also express more enthusiasm for the aid package.Footnote 18

Finally, we turn our attention to H4―whether trust in government conditions citizens’ support for donor-controlled as opposed to government-controlled aid. As shown in Table 6, the interaction terms between the donor-control and trust-in-government variables are negative in all three cases, although they are statistically significant only for Indonesia (at the 10% level) and Nepal (at the 1% level), and not for Myanmar. As clearly illustrated in the marginal effects plot in Fig. 3, as trust in government increases, reactions to donor-controlled aid become negative. These results are consistent with H4. Importantly, Fig. 3 helps us solve the puzzle presented in Table 3: it provides a convincing explanation for why average support for donor-controlled aid differs between Indonesia and Myanmar, on the one hand, and Nepal, on the other. Control of aid by the donor rather than the government reduces levels of support for aid in Indonesia and Myanmar because, as expressed by the thick vertical lines, those respondents located at the median position in terms of their trust in government are found where the marginal effect of control by the donor is significantly negative. In Nepal, by contrast, the median respondents are found where the marginal effect of control by the donor is significantly positive, which explains why, in Table 3, we observe a statistically significant positive effect of control by the donor in the case of Nepal. Figure 3 suggests that the heterogenous ATEs are due to variation across countries in the distribution of trust in government, a key variable moderating the effect of the control-of-aid treatment.

The results shown above together imply that trust in government is more important than trust in donors as a predictor of respondents’ attitudes toward aid ownership. As a robustness check, we run additional estimations by including in each regression model a three-way interaction term of the control-of-aid treatment, the trust-in-donor treatment, and the level of trust in government. As shown in Table A3 as well as Figures A3 and A4 in the SI, our finding that trust in government, rather than trust in the donor, is more prominent in influencing respondents’ preferences between donor- and government-controlled aid robustly holds: regardless of whether they trust the donor or not, respondents tend to prefer government-controlled aid when they trust their government and donor-controlled aid when they do not.

We also look to see if there is evidence that trust in government is proxying for nationalistic attitudes or perceptions of aid dependence. As can be seen in Tables A4 and A5 in the SI, these variables do not moderate the control-of-aid treatment, giving us increased confidence that trust in government is the appropriate concept to focus on as a moderator.

In addition, we assess the robustness of the results by using the kernel smoothing method for diagnosing non-linearities in interactions suggested by Hainmueller et al. (2019); as the authors describe, the method is “fully automated (e.g., researchers do not need to select a number of bins) and characterizes the marginal effect across the full range of the moderator, rather than at just a few evaluation points” (173). As shown in Figures A5 and A6 in the SI, the marginal effects of control by the donor are weakly decreasing in the pooled data across the range of values of trust in government; at moderate levels of trust in government, there is a leveling of the marginal effect curve driven primarily by the data from Nepal, where there is a slight uptick in the country-specific marginal effect at levels of trust in government between 5 and 7.5 followed by a decrease in marginal effects thereafter. These results are generally consistent with H4.

Furthermore, we check the robustness of the results by excluding from the analysis those respondents who answered “Don’t Know” when we asked them, subsequent to our outcome variable question, which donor they had been thinking about in response to the assigned stimulus. These people arguably applied the least cognitive effort to engaging with the stimuli, since they did not undertake the task that was asked of them (i.e., “think of a foreign country that you (do not) trust”). As can be seen in Table A6 and Figure A7 in the SI, the results for our main hypothesis (H4) remain unchanged.

Finally, we address a concern that partisan bias, rather than trust in government, may moderate the effect of the control-of-aid treatment. To do so, we reanalyze our regression models by including interactions between indicators of partisanship and the control-of-aid treatment. Due to concerns about question sensitivity, and the overwhelming support that the incumbent government received in the most recent election in Myanmar, we did not include a question on party identification in the survey we conducted in Myanmar. The additional analyses we conduct are thus limited to Indonesia and Nepal, where we found earlier in this manuscript significant results for the moderating effect of trust in government. Table A7 in the SI provides the list of political parties to which our respondents in Indonesia and Nepal, respectively, feel close. As shown in Table A8 and Figure A8 in the SI, trust in government moderates the effect of the control-of-aid treatment on levels of support for aid projects in a manner consistent with our main argument (H4), even after considering the possibility that each respondent’s party affiliation serves as a moderator.

5 External Validity

In the previous section, we presented results from survey samples from the largest cities in Indonesia, Myanmar, and Nepal. Table 2 shows that when evaluating aid packages, respondents react positively when prompted to think about a donor that they trust. As shown in Table 4, however, when considering the question of control over aid, reactions to a stimulus about donor control vary substantially by the level of respondents’ trust in their own government. Figure 3, based on the estimates in Table 4, provides evidence of parallel patterns across the three surveys, where those individuals who most strongly trust their government react negatively to the idea of donor control, while those individuals who lack trust in their government either do not react to information about donor control (Myanmar) or else react positively to that information (Nepal and possibly Indonesia). As these surveys were based on representative random samples of the three cities, we feel comfortable asserting that our results generalize to their respective cities. Are they transportable to other areas of the countries and – more importantly – to other settings?Footnote 19

We approach these questions in four steps. First, we apply the M-STOUT framework of Findley et al. (2021) to argue why we think that the results should apply to a broad range of aid-receiving countries. Second, we explore within-country transportability using a predictive cross-validation method. Third, we provide a data-based situation of our three country cases vis-à-vis other aid receiving states. Finally, we discuss how cross-country results found in Clark et al. (2023) that draw on 27 African countries parallel our results.

For theoretical reasons, we think that our findings are highly transportable to other settings. Findley et al. (2021) argue that transportability should be assessed in terms of M-STOUT: mechanisms, settings, treatments, outcomes, units, and time. Our treatments, outcomes, and units are all quite common. We provide informational treatments that speak about foreign assistance, foreign countries, and trust in foreign countries in ways that we think would be applicable in any setting where there is at least some minimal level of foreign assistance present. Likewise, the outcome variable and the moderating variable are straightforward evaluative questions that might be asked in a wide variety of settings, and the units of analysis are individual survey respondents in a random-sample survey. The broadly applicable nature of these three elements of the research design suggest a high degree of transportability to settings beyond the three we study.

More importantly, the theoretical mechanism at work is one that we expect to operate in a wide variety of settings. Our findings involve correlations between trust and support for aid (H1 and H3) and trust in government and attitudes toward donor-versus-government control over aid (H4). Given the centrality of trust-based mechanisms to so many aspects of social behavior (e.g., Cook, 2001; Hardin, 2002), we believe the cognitive mechanisms underlying these reactions found in our study are highly transportable, such that we would observe similar heterogeneous effect patterns in many settings. For H1 and H3, it is hard to think of contexts where trust in donors or trust in government would correspond to less support for aid in general.Footnote 20 For H4, it is hard to think of contexts where additional moderating factors would reverse this relationship such that trust in government would be correlated with positive reactions to external impositions. Therefore, our assessment is that we should expect to find evidence of these same patterns in many other places.

With regard to setting, we explore the transportability of our findings empirically. We start by acknowledging that each of our surveyed cities―Jakarta, Yangon and Kathmandu―is likely distinct from other areas in each surveyed country in various aspects and to varying degrees. For example, using individual-level data collected by the World Values Survey (Indonesia and Myanmar) and the Asia Foundation (Nepal), we find that citizens in our surveyed cities have, on average, less trust/confidence in their government compared to those in other parts of the country, although this difference is statistically significant only in Indonesia. Citizens in Jakarta and Kathmandu also tend to have higher incomes than those in other regions of Indonesia and Nepal, respectively (see Figure A9 in the SI for comparisons between the surveyed cities and the remainder of the countries using secondary data and Figures A10 to A13 in the SI, which show the distribution of data for comparable variables found in our original data and secondary data).

The question is: do these differences matter for transporting our results to cities, towns and villages we did not survey? We answer this question by exploiting within-sample variation to see if our results are driven by parts of the sample that might more-or-less closely reflect regions of the country beyond the cities for which we have data. To check whether particular characteristics of our sample influence our estimates, we make use of the within-city administrative districts where our sample was enumerated.Footnote 21 We sequentially drop one district at a time from the sample in each country, run our regression with an interaction term for testing H4, use the coefficients from that regression to predict the values for the omitted administrative districts, and calculate root mean squared error (RMSE) statistics. We then plot these RMSE statistics against district-level averages of the seven covariates in our analyses (trust in government, percent female, age, income, nationalistic attitude, perceived aid dependence, and trust in international organizations). If any of the covariates predicts the RMSE, this indicates that generalizing to places with higher or lower values of that covariate could be problematic.

In almost all cases, we do not see evidence that the covariates correlate with prediction error.Footnote 22 For example, out-of-sample prediction errors in Jakarta do not greatly differ among districts with varying levels of trust in government (see Figure A17 in the SI). This result suggests that our inferences may apply to other parts of Indonesia, as long as their average level of trust in government is within the range of the averages in the surveyed districts in Jakarta, in this case, between 4–10 on a 10-point scale. District-level averages of trust in government in Kathmandu also vary widely from 1–8 (see Figure A16), suggesting our inferences may apply to wide range of administrative units in Nepal. While the corresponding distribution of district-level averages for Yangon is tighter, ranging from 6–10, given the overwhelming support for the incumbent across the country in the elections before and after our survey, we expect trust in government to have been similarly high across most districts during the survey, and thus believe, our inferences may similarly apply to other districts. Overall, this analysis provides evidence that our results would likely hold outside of the cities where we conducted our surveys.

What about transportability to settings beyond the three countries that we study? We have described above contextual variation across the three cases. Nepal has experienced high levels of aid dependence for decades. At the time of our survey, Myanmar, after a long period of international sanctions and attempted autarky, had recently opened to foreign assistance, which was entering in substantial amounts. Indonesia, on the other hand, has not been a major recipient of foreign aid per se in recent decades, although it continues to borrow at non-concessional rates from foreign development agencies for major infrastructure projects. Relatedly, the three countries vary in their level of development and their experience with democracy. That we see parallel results across these three diverse cases in terms of how people react to the trusted donor treatment (relative to the untrusted donor treatment) and how they react to the idea of donor control (conditional on their level of trust in their own government) suggests that there is a broad range of cases within which we might expect to continue to see parallel results, again implying a high degree of transportability.

We find Egami and Hartman’s (2023) discussion of the “range assumption” useful for thinking about this. For example, as shown in Figure A20 in the SI, based on per capita GDP, 54% of least developed and lower-middle-income aid-receiving countries fall between Indonesia and Nepal—countries where we found statistically significant interactions between the donor-control treatment and trust in government. The corresponding percent of coverage across other variables is 50% in terms of aid dependence and 17% in terms of political regime (see Figure A21 in the SI for the distribution of aid-receiving countries including also those with upper middle incomes).Footnote 23 This reflects a relatively large number of countries within which we could expect similar results.

Furthermore, while we cannot precisely predict the countries in which the median voter will prefer donor-controlled aid to government-controlled aid, our results suggest that those countries where the median voter has low trust in government (like Nepal) should demonstrate an average preference for donor control, whereas those countries where the median voter has high trust in government (like Indonesia and Myanmar) should demonstrate an average preference for government control.

Finally, a recent working paper by Clark et al. (2023) provides empirical evidence of the transportability of our findings. Those authors use novel questions about support for donor conditionality (i.e., donor control) on the Afrobarometer to show that trust in the president and trust in the ruling party negatively correlate with support for donor conditionality. Across 27 countries, the point estimates for the correlation between trust in government and support for donor conditionality are negative in 26 cases and extremely close to 0 in the one case where they are positive. The findings in the paper imply that the phenomenon that we identify here – people reacting to donor control in different ways depending on their level of trust in their current government – are likely to obtain in many aid-receiving countries around the world.

6 Discussion

Scholars of foreign aid and development practitioners have long wrestled with the issue of who should control the implementation of foreign aid projects. On the one hand, concerns about the quality of governance in aid-receiving countries have historically led foreign-aid donors to exert significant direct control over foreign aid flows and to employ extensive monitoring mechanisms in aid projects (Winters, 2010). On the other hand, some scholars and practitioners claim that foreign aid performs most efficiently when it is provided as budget support, flowing through country systems and funding government-run programs (Cordella & Dell’Ariccia, 2007). As part of the aid effectiveness agenda in the early twenty-first century, members of the international community started campaigning for increased “country ownership” of foreign aid, calling for aid-receiving governments to have more control over how aid is used. However, despite the salience of this issue, relatively little scholarship has tried to study public perceptions of the desirability of country ownership.

We contribute to this understudied area by presenting results from parallel survey experiments in Myanmar, Nepal, and Indonesia. In these experiments, we highlight the role of trust that citizens have in donors and governments respectively. Given that trust forms the foundations of human interactions and organizations (Cook, 2001; Hardin, 2002), we are convinced that this concept must also occupy an important place in understanding the aid-related attitudes of citizens in developing countries.

Based on the micro-level data we collected across the cases, it is clear that ordinary citizens in developing countries are not uniformly enthusiastic about the principle of country ownership. To be more specific, publics on average seem to prefer government-controlled projects in Myanmar and Indonesia, but ordinary citizens in Nepal seem far more inclined to have aid implementation be controlled by the donors. We resolve these apparently contradictory findings by showing that attitudes toward donor control vary with respondents’ level of trust in their government: where the majority of the population has relatively high (low) trust in government, there is likely to be less (more) support for donor control. On the other hand, we find surprisingly limited evidence that trust in the donor matters.

Our finding from Nepal resembles the results of earlier studies in Uganda (Baldwin & Winters, 2020; Findley et al., 2017a, b; Milner et al., 2016). Those studies show evidence consistent with our own that individuals who do not support the government or who perceive high levels of government corruption are more likely to prefer donor-funded projects (Findley et al., 2017a, b; Milner et al., 2016). Our research shows that this moderation of the reaction to donor control is persistent across three additional cases, confirming that the mechanism underlying preferences regarding control over aid generalizes to countries with higher average levels of trust in government. Since we observe these parallel patterns of trust in government and support for donor-controlled aid in countries with varying levels of aid dependence, economic development, and democratic experience, we expect these findings to be transportable to a relatively wide range of countries. Relatedly, Clark et al. (2023) show evidence from Afrobarometer data that there is a consistent correlation between trust in government and attitudes toward donor conditionality.

In addition to providing results across three countries, our parallel survey experiments differed from that reported in Milner et al. (2016) and the associated studies in several ways. Our experimental stimulus explicitly manipulates the idea of donor versus government control, whereas the latter studies’ manipulation only changes reported funding source. While we think it is quite likely that their findings originate in perceptions of greater external control when donors fund projects, our findings give us confidence that this is indeed the case. Furthermore, we directly manipulate the characteristic of the donor that we care about (i.e., whether the donor is one that the respondent trusts or does not trust). Similar to the limited variation that we see across our trusted donor / non-trusted donor conditions, those authors also show a surprising lack of variation across different funders named in their experiment. As we explicitly focus on trust in the donor, we reveal that even a very direct statement of a logic by which respondents should or should not prefer donor control is less impactful than the respondents’ background perceptions of their own government’s trustworthiness. Our experimental set-up lets us explicitly contrast both variation in project control and variation in trust in the donor.

In sum, the argument and findings presented in this paper reinforce the idea that country ownership hardly represents the same phenomenon in all countries – indeed not even across all citizens. Having funds on-treasury and being able to decide how funds are spent may be desired and welcomed by governments of aid-receiving countries. Whether such an arrangement is also desired and welcomed by the citizens of those countries, however, is a different matter: a matter of trust in their own governments. When the international aid community upholds the principle of country ownership, the emphasis seems to be placed almost exclusively on economic and administrative efficiencies. Furthermore, the Paris Declaration and Accra Agenda for Action, which include the principle of country ownership, are not clear on how ownership should be established, namely who should be part of the decision regarding how aid should be used and implemented. We contend that the true meaning of ownership must include the political will of the public in a given aid-receiving country. As we have shown in this paper, the people’s will, expressed as their preference for aid controlled by their own government, may not be as solid as the international aid community seems to take for granted.

Finally, we suggest some directions for future research, building on what we have presented here. First, our argument and findings highlight citizens’ trust in donors and government as important predictors, but we have not systematically explored their sources. It is probably safe to assume, as we have done in this paper, that citizens’ trust in their own government is affected by political traits, such as ideology and partisanship, as well as social attributes, such as ethnicity and minority-status. On the other hand, how individuals form their trust in particular donors is likely a far more complicated question, requiring detailed research. There are perhaps a variety of reasons why citizens perceive certain donors to be trustworthy, which may range from their record of aid performance to more subjective stereotypes of image and reputation. Probing how publics form their trust in donors is warranted given that, for the sake of accountability and efficacy, donors themselves should be interested in appealing to the minds of the publics and capturing their trust.

Second, in our experimental design, respondents’ trust toward the anticipated donor is part of the treatment, but their trust in government is not. Assuming that respondents’ attitudes toward their own government are relatively stable, we measure them through standard survey questions prior to the experiment. It may, however, be possible to prime trust in government experimentally, something that would give us additional confidence that this is the key moderating factor for how people react to donor control.

Data Availability

Data and replication code for this article, as well as the supplementary information file, are available on the Review of International Organizations webpage.

Notes

The Paris Declaration separates the principle of countries setting their own development strategies (“ownership”) from that of donors’ use of local systems (“alignment”). The principle of alignment was folded into ownership at the high-level forum in Accra. See https://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/parisdeclarationandaccraagendaforaction.htm (accessed 15 May 2023).

For a critical view on the value of the idea of country ownership, see Buiter (2007).

A recent working paper, which we discuss in more depth below, finds substantial support for donor conditionality in the Afrobarometer data and in an original survey in Kenya (Clark, Dolan, and Zeitz 2023).

The survey in Myanmar was conducted in January and February 2019, two years before the democratically-elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government was overthrown in a military coup.

Abdoulaye Wade. (2008 January 23). Time for the West to Practise What It Preaches. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/5d347f88-c897-11dc-94a6-0000779fd2ac (accessed 15 May 2023). For more official and popular views of China’s engagement in Africa, both positive and negative, see Hanauer and Morris (2014).

The Sankei Shimbun. (2022 April 23). Sri Lanka and the Danger from China’s Debt Traps. Japan Forward. https://japan-forward.com/sri-lanka-and-the-danger-from-chinas-debt-traps/ (accessed 15 May 2023). See also the discussion of perceptions of Chinese aid in Blair and Roessler (2021).

Like the literature on aid and autocratic political survival, research on aid and corruption generates mixed results; see, for example, Okada and Samreth (2012).

As detailed below, the survey in Myanmar was conducted before the military coup in 2021.

After the military coup in 2021, sanctions targeted at Myanmar were resumed.

Our descriptions of donor control and government control are quite stark. In reality, even if donors exert significant control over aid, governments nonetheless retain formal or informal mechanisms for shaping the specific features of aid packages. Similarly, even when aid is “on-budget/on-treasury,” donors still have levers that they can use to influence the implementation of projects. We used forceful language to convey the core ideas to respondents.

We recognize the possibility that respondents, when asked to name the trusted (or untrusted) donor that they had in mind, simply provided the first donor name that came to mind, regardless of its fit with the stimulus. Although the parallels between the two lists in the Indonesian case might raise a concern in this regard, we do not see this pattern in the Myanmar and Nepal data, where the trusted and untrusted lists are more distinct. Given this and as this item was asked after the outcome variable, we are confident that our results originate in the generic information that we provided in the stimulus.

We speculate that this large movement in Myanmar may reflect a historical context in which citizens’ default perceptions of external actors are quite low because of the prolonged international sanctions imposed against the previous military regime. In Indonesia and Nepal, in contrast, people have seen a steady flow of aid from a variety of donors, perhaps making them more sanguine about supporting aid regardless of the source.

As above, it is important to keep in mind that we ran the survey in Myanmar before the military coup in February 2021. Thus the data reflect citizens’ trust in the democratically-elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government. Initially elected in 2015, ending a fifty-year period of military rule, the NLD government received a landslide endorsement of its rule in the 2020 elections, making it unsurprising that we see such high levels of trust in government in the sample.

The patterns that we observe in Fig. 2 are consistent with measures of trust from other recent surveys. In Wave 7 of the World Values Survey, three-quarters of respondents from the Yangon region of Myanmar say that they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the government, whereas 73 percent of respondents from Jakarta say the same. Wave 7 of the World Values Survey did not include Nepal. Survey data from The Asia Foundation (2022), however, shows that only one-third of respondents in Kathmandu express “full” or “moderate” trust in the national government. As the World Values Survey samples are not identifiable at the city level, the statistics above rely on information from larger geographic regions containing Yangon, while for Jakarta, we identified, based on geocoded data, that one of the interview points was located in Jakarta (and that the other interview points were located in other cities).

Political partisanship is another variable that might correlate both with trust in government and support for aid. Because of sensitivities around asking about partisan identification in Myanmar, we have a measure of partisanship for only Indonesia and Nepal. We therefore do not include it as a covariate in Table 5 below. In the SI, we show the robustness of our H4 claims about trust in government to the inclusion of partisan interactions for Indonesia and Nepal.

While the observational nature of this data means that we cannot guarantee that there are not additional unmeasured confounders, the three variables capturing respondents’ attitudes toward international relations and foreign affairs are likely to capture much of the potential background covariance between trust in government and support for aid.

We take the terminology of transportability from Findley et al. (2021).

The term “district” here is used in a generic sense; it refers to the local units used to subdivide the cities from which we collected data. In Jakarta, Yangon and Kathmandu, these units are referred to as subdistricts, districts and wards, respectively.

We discuss the one exception – the case of percent female in Nepal – in more detail in Section A5 in the SI.

Note that the coverage for political regime is the least exactly because we chose our cases based on the fact that we wanted to study countries where public opinion might matter for decision making.

References

Alrababa’h, A., Myrick, R., & Isaac, W. (2020). Do Donor Motives Matter? Investigating Perceptions of Foreign Aid in the Conflict in Donbas. International Studies Quarterly, 64(3), 748–757.

Andersen, J. J., Johannesen, N., & Rijkers, B. (2022). Elite Capture of Foreign Aid: Evidence from Offshore Bank Accounts. Journal of Political Economy, 130(2), 388–425.

Asia Foundation. (2022). Survey of the Nepali People (2017–2020). https://doi.org/10.26193/K9QPBH. ADA Dataverse, V1.

Baldwin, K., & Winters, M. S. (2020). How Do Different Forms of Foreign Aid Affect Government Legitimacy? Evidence from an Informational Experiment in Uganda. Studies in Comparative International Development, 55(2), 160–183.

Bermeo, S. B. (2016). Aid Is Not Oil: Donor Utility, Heterogeneous Aid, and the Aid-Democratization Relationship. International Organization, 70(1), 1–32.

Blair, R. A., & Roessler, P. (2021). Foreign aid and state legitimacy: evidence on Chinese and US Aid to Africa from surveys, survey experiments, and behavioral games. World Politics, 73(2), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004388712000026X

Bräutigam, D. A., & Knack, S. (2004). Foreign Aid, Institutions, and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 52(2), 255–285.

Brutger, R. Kertzer, J. D., Renshon, J., Tingley, D., & Weiss, C. M. (2022). Abstraction and detail in experimental design. American Journal of Political Science, 67(4), 979–995.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Alastair, S. (2007). Foreign Aid and Policy Concessions. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(2), 251–284.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Alastair, S. (2009). A Political Economy of Aid. International Organization, 63, 309–340.

Buiter, W. H. (2007). ‘Country Ownership’: A Term Whose Time Has Gone. Development in Practice, 17(4–5), 647–652.

Clark, R., Dolan, L. R., & Zeitz, A. O. (2023). Accountable to Whom? Public Opinion of Aid Conditionality in Recipient Countries, Cornell University. https://www.peio.me/wp-content/uploads/PEIO15/PEIO15_paper_56.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2024

Clist, P., Isopi, A., & Morrissey, O. (2012). Selectivity on Aid Modality: Determinants of Budget Support from Multilateral Donors. The Review of International Organizations, 7(3), 267–284.

Cook, K. S. (2001). Trust in Society. Russell Sage Foundation.

Cordella, T., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2007). Budget Support Versus Project Aid: A Theoretical Appraisal. The Economic Journal, 117(523), 1260–1279.

Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Caughey, D. (2018). Information Equivalence in Survey Experiments. Political Analysis, 26(04), 399–416.

Deutsch, K. W., et al. (1957). Political Community and the North American Area. Princeton University Press.

Dietrich, S. (2011). The Politics of Public Health Aid: Why Corrupt Governments Have Incentives to Implement Aid Effectively. World Development, 39(1), 55–63.

Dietrich, S., & Wright, J. (2015). Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa. Journal of Politics, 77(1), 216–234.

Egami, N., & Hartman, E. (2023). Elements of External Validity: Framework, Design, and Analysis. American Political Science Review, 117(3), 1070–1088.

Findley, M. G., Harris, A. S., Milner, H. V., & Nielson, D. L. (2017a). Who Controls Foreign Aid? Elite versus Public Perceptions of Donor Influence in Aid-Dependent Uganda. International Organization, 71(4), 633–663.

Findley, M. G., Milner, H. V., & Nielson, D. L. (2017b). The Choice among Aid Donors: The Effects of Multilateral vs. Bilateral Aid on Recipient Behavioral Support. Review of International Organizations, 12(2), 307–334.

Findley, M. G., Kikuta, K., & Denly, M. (2021). External Validity. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 365–393.

Foster, A. (2021). Is neo-colonialism disguised as foreign aid? Guyana Chronicle. https://guyanachronicle.com/2021/07/25/is-neo-colonialism-disguised-as-foreign-aid/. Accessed 26 Aug 2022

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. The Free Press.

Goldsmith, B. E., Horiuchi, Y., & Wood, T. (2014). Doing Well by Doing Good: The Impact of Foreign Aid on Foreign Public Opinion. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 9, 87–114.

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Yiqing, Xu. (2019). How Much Should We Trust Estimates from Multiplicative Interaction Models? Simple Tools to Improve Empirical Practice. Political Analysis, 27(2), 163–192.

Hanauer, L., & Morris, L. J. (2014). Chinese engagement in Africa: Drivers, reactions, and implications for U.S. policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corportation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR521

Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and Trustworthiness. Russell Sage Foundation.

Hoffman, A. M. (2002). A Conceptualization of Trust in International Relations. European Journal of International Relations, 8(3), 375–401.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2016). The Grand Bargain -- A Shared Commitment to Better Serve People in Need. Istanbul. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain/grand-bargain-shared-commitment-better-serve-people-need-2016. Accessed 1 Nov 2023

Jackson, J. & Gau, J. M. (2016). Carving up concepts? Differentiating Between trust and legitimacy in public attitudes towards legal authority. In E. Shockley, T. M. Neal, L. M. PytlikZillig, & B. H. Bornstein (Eds.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on trust: Towards theoretical and methodological integration (pp. 49–69). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-22261-5_3.

Jayawickrama, J. (2018). Humanitarian aid system is a continuation of the colonial project. AlJazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2018/2/24/humanitarian-aid-system-is-a-continuation-of-the-colonial-project. Accessed 15 May 2023

Knack, S. (2013). Aid and Donor Trust in Recipient Country Systems. Journal of Development Economics, 101, 316–329.

Knack, S. (2014). Building or Bypassing Recipient Country Systems: Are Donors Defying the Paris Declaration? The Journal of Development Studies, 50(6), 839–854.

Kono, D. Y., & Montinola, G. R. (2009). Does Foreign Aid Support Autocrats, Democrats, or Both? Journal of Politics, 71(2), 704–718.

Kydd, A. (2000). Trust, Reassurance, and Cooperation. International Organization, 54(2), 325–357.

Kydd, A. (2007). Trust and Mistrust in International Relations. Princeton University Press.

Langan, M., & Scott, J. (2011). The false promise of Aid for Trade. Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper, 160. http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1983209. Accessed 26 Aug 2022

Licht, A. A. (2010). Coming into Money: The Impact of Foreign Aid on Leader Survival. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(1), 58–87.

Milner, H. V., Nielson, D. L., & Findley, M. G. (2016). Citizen Preferences and Public Goods: Comparing Preferences for Foreign Aid and Government Programs in Uganda. Review of International Organizations, 11(2), 219–245.

Molenaers, N., Gagiano, A., & Smets, L. (2017). Introducing a New Data Set: Budget Support Suspensions as a Sanctioning Device: An Overview from 1999 to 2014. Governance, 30(1), 143–152.

Moyo, D. (2009). Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Nyikadzino, G. (2021). Aid to Africa: a deceptive neo-colonial tool enforcing mental slavery without restraint. Ubuntu Times. https://www.ubuntutimes.com/aid-to-africa-a-deceptive-neo-colonial-tool-enforcing-mental-slavery-without-restraint/. Accessed 26 Aug 2022

Okada, K., & Samreth, S. (2012). The Effect of Foreign Aid on Corruption: A Quantile Regression Approach. Economics Letters, 115(2), 240–243.

Schraeder, P. J., Hook, S. W., & Taylor, B. (1998). Clarifying the Foreign Aid Puzzle: A Comparison of American, Japanese, French and Swedish Aid Flows. World Politics, 50(2), 294–323.

Svensson, J. (2000). Foreign Aid and Rent-Seeking. Journal of International Economics, 51(2), 437–461.

Winters, M. S. (2010). Choosing to Target: What Types of Countries Get Different Types of World Bank Projects. World Politics, 62(3), 422–458.

Wong, S. (2012). What Have Been the Impacts of World Bank Community-Driven Development Programs CDD Impact Evaluation Review and Operational and Research Implications. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/967431468161087566/What-have-been-the-impacts-of-World-Bank-Community-Driven-Development-Programs-CDD-impact-evaluation-review-and-operational-and-research-implications. Accessed 12 Feb 2024

Wright, J. (2009). How Foreign Aid Can Foster Democratization in Authoritarian Regimes. American Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 552–571.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Takaaki Kobayashi, Yoshiko Kojo, and Kazuto Otsuki for comments received at an early stage of this project. Thanks to Kate Baldwin for comments on an earlier version of this paper, which was presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, and to three anonymous reviewers for excellent comments.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Project Number 17H00974). The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article. This research was reviewed by the Ethics Review Committee on Research with Human Subjects of Waseda University (2018-229).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The order of authors reflects the significance of KH’s contributions to the analysis, MK’s role in securing the funding for the study, and ongoing rotation in the author order among participants in this collaboration. Author contributions to research design and conceptualization: KH (10%), GM (30%), MW (30%), and MK (30%); statistical analysis KH (70%), GM (10%), MW (10%), and MK (10%); and writing: KH (20%), GM (30%), MW (30%), and MK (20%).

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Responsible editor: Axel Dreher

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirose, K., Montinola, G.R., Winters, M.S. et al. A matter of trust: Public support for country ownership over aid. Rev Int Organ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-024-09534-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-024-09534-7