Abstract

It is commonly accepted that developing countries pursue the creation of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). However, it is relatively unknown what role developed countries play in the creation of BITs. When negotiating FDI deals, multinational corporations (MNCs) anticipate potential investment disputes between themselves and the host government. MNCs seek to reduce future investment risks, and asking their own government to secure BITs with the host country is an attractive option for doing so. To test my argument about capital-exporting actors influencing BITs, I analyze FDI project announcement data, which captures the timing of when MNCs finalize their plans to engage in FDI. The findings show that MNCs’ already-planned FDI is strongly associated with the probability of subsequent BIT signing between the home and host country. Moreover, by matching firm-level financial information with FDI project announcements, I show that home countries are more likely to establish BITs with host countries when large firms are the source of the planned FDI. These findings suggest that BIT creation is not driven solely by host countries’ economic needs, but also by home countries’ desire to protect their politically privileged firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets and replication codes are available on the Review of International Organization’s webpage.

Notes

See Büthe and Milner (2008).

Neumayer (2006), for instance, highlights how MNCs may lobby for the creation of BITs. Other works evaluate developed-country MNCs and investment treaties but mostly focus on arbitration (Pelc, 2017& Simmons, 2014). Also, Kerner and Lawrence (2014) employ US MNCs’ investment data to evaluate MNC investments in response to BITs.

See Allee and Peinhardt (2010).

He also notes that these efforts contributed to the development of international dispute tribunals and BIT programs.

Moreover, recent research indicates that developing countries are more likely to sign BITs when they are domestically vulnerable, such as during episodes of civil conflict (Billing & Lugg, 2019).

Milner (1988)’s seminal work illustrates this point, showing how the internationalization of US firms substantially contributed to pressures for decreasing trade barriers.

It is conceivable that MNCs may try to influence BITs by lobbying host governments directly. However, MNCs tend to rely on their links with their home governments to handle international legal arrangements. For instance, see Gertz (2018).

Siemens, a German manufacturing conglomerate, began seeking its first investment opportunities in China in the late 1970s by holding its first major exhibition in Shanghai. Daimler-Benz first established its business, Beijing Jeep Corporation, in 1983 with an initial outlay of nearly $224 million (Peng, 2013, 420). Liebherr Haushaltgerate, an appliance maker, also concluded its first investment in the early 1980s (Yueh, 2011, 122).

A few studies suggest contrasting results. For example, see Yackee (2010).

These companies were headquartered primarily in the US, Canada and Western Europe.

These survey respondents were executives in large firms that tend to contract closely with the state such as resource extraction firms.

This letter is available at https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-2013-0019-0054. Accessed 22 Mar 2019.

Lobby View contains 380 BIT-related lobbying reports. Accessed 31 May 2020.

The lobbying reports related to BITs indicate that government bodies, which lead the formation and ratification of BITs, such as the White House, USTR, US Department of State, US Department of Commerce, US Department of the Treasury, and US Senate, are subject to corporate lobbying activities.

The detailed transcript can be found here: https://www.c-span.org/video/?32666-1/north-american-free-trade-agreementhttps://www.c-span.org/video/?32666-1/north-american-free-trade-agreement.

The subsequent reactions to NAFTA also demonstrate corporate influence in the creation of international policy. For instance, see Manger (2009).

The day before the BIT was signed, the STX Group already held a South Korea-Azerbaijan Culture Night that the Azerbaijani Ambassador attended (STX Corporation, 2007).

As UNCTAD only provides annual FDI data, a year’s worth of bilateral FDI outflows were spread evenly over a 12 month period to be able to compare the UNCTAD and fDi Markets’ data. See for details: https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/webdiaeia2014d3_ESP.pdf.

The survey and policy report can be found here: https://www.keidanren.or.jp/english/policy/2002/042/index.html.

The PM3 was a major-sized investment project that was approved for US $40 million loans by the Asian Development Bank. The details of the PM3 investment project can be assessed from here: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/66394/36901-vie-pcr.pdf

The country reports can be found from here: http://www.jmcti.org/cgibin/main_e.cgi?Kind=Country.

Of the 391 BITs that developed home countries have signed during the examined period, 376 were with developing partner countries.

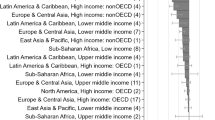

According to IMF classification, 39 countries are defined as advanced economies. Eight countries, including San Marino and Puerto Rico, are dropped from the analysis because there is no investment data available or they have too few outward-oriented firms.

Developed countries did not sign a BIT twice with the same developing country during the examined period.

The fDi Markets database collects information about the volume of announced FDI by searching thousands of media sources, market research and investment agency reports, and internal Financial Times sources (fDi Markets, 2019).

The investment amounts are aggregated across the examined period of this study.

These are 10% of all matched firms. A detailed description of the matching process is reported in Online Appendix.

For the analysis that employs a proportional measure to explain the formation of international agreements, see Manger (2012).

This variable ranges from -10 to 10 and higher values indicate more democratic political institutions.

PTA data is from the Design of Trade Agreements (DESTA) dataset (Dür et al., 2014) and BIT data is from UNCTAD’s international investment agreements navigator. Finally, pairs of dyadic controls are included.

I also run a series of duration models for the robustness checks. These additional models are discussed in the empirical result section.

Descriptive statistics on variables, host-home country list, and FDI dataset are available in Online Appendix

Given that BIT signing is infrequent events that are being examined annually, the effect of developed home country MNCs’ FDI plans is substantial.

Albino-Pimentel et al. (2018) also point out the possible measurement error due to estimated values in the dataset.

Nairobi is Samsung’s headquarter, where the company supplies its products to 16 African countries. See https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/Samsung-to-open-phone-and-TV-assembly-plant-in-Kenya/539550-1738928-ns8jka/index.htmlhttps://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/Samsung-to-open-phone-and-TV-assembly-plant-in-Kenya/539550-1738928-ns8jka/index.html.

In such a scenario, BITs are established regardless of whether home MNCs lobby for them because MNCs make investments when they become certain that a BIT is about to be formed.

References

Aggarwal, V. K. (1992). In The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, JSTOR, pp 35–54.

Aisbett, E. (2007). Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: correlation versus causation.

Albino-Pimentel, J, Dussauge, P., & Shaver, J. M. (2018). Firm non-market capabilities and the effect of supranational institutional safeguards on the location choice of international investments. Strategic Management Journal, 39(10), 2770–2793.

Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & et al. (2004). FDI and economic growth: the role of local financial markets. Journal of International Economics, 64(1), 89–112.

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2010). Delegating differences: Bilateral investment treaties and bargaining over dispute resolution provisions. International Studies Quarterly, 54(1), 1–26.

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2014). Evaluating three explanations for the design of bilateral investment treaties. World Politics, 66(1), 47–87.

Alschner, W., & Skougarevskiy, D. (2016). Mapping the universe of international investment agreements. Journal of International Economic Law, 19(3), 561–588.

Baccini, L., Pinto, P. M., & Weymouth, S. (2017). The distributional consequences of preferential trade liberalization: firm-level evidence. International Organization, 71(2), 373–395.

Baccini, L., & Urpelainen, J. (2012). Strategic side payments: preferential trading agreements, economic reform, and foreign aid. The Journal of Politics, 74(4), 932–949.

Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 430–456.

Batty, D. (2008). Twentieth century fox launches Bollywood venture. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2008/sep/10/bollywood.newscorporation. Accessed 12 November 2022.

Beazer, Q. H., & Blake, D. J. (2018). The conditional nature of political risk: How home institutions influence the location of foreign direct investment. American Journal of Political Science, 62(2), 470–485.

Berger, A., Busse, M., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2011). More stringent BITs, less ambiguous effects on FDI? Not a bit!. Economics Letters, 112(3), 270–272.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Schott, P. K. (2009). Importers, exporters and multinationals: a portrait of firms in the US that trade goods. In Producer dynamics: New evidence from micro data (pp. 513–552). University of Chicago Press.

Betz, T., Pond, A., & Yin, W. (2021). Investment agreements and the fragmentation of firms across countries. The Review of International Organizations, 16(4), 755–791.

Billing, T., & Lugg, A. D. (2019). Conflicted capital: the effect of civil conflict on patterns of BIT signing. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(2), 373–404.

Bombardini, M., & Trebbi, F. (2012). Competition and political organization: Together or alone in lobbying for trade policy?. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 18–26.

Bonnitcha, J., Poulsen, L. N. S., & Waibel, M. (2017). The political economy of the investment treaty regime. London: Oxford University Press.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2008). The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: increasing FDI through international trade agreements?. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 741–762.

Carter, D. B., & Signorino, C. S. (2010). Back to the future: Modeling time dependence in binary data. Political Analysis, 18(3), 271–292.

Chilton, A. S. (2016). The political motivations of the United States’ bilateral investment treaty program. Review of International Political Economy, 23(4), 614–642.

Diplomacy. (2006). The summit meeting between Roh-Ilham Aliyev. http://www.diplomacykorea.com/magazine/sub.asp?pub_cd=200605&c_cd=13&srno=355. Accessed 12 November 2022.

Drezner, D. W. (2008). All politics is global: Explaining international regulatory regimes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dür, A., Baccini, L., & Elsig, M. (2014). The design of international trade agreements: introducing a new dataset. The Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 353–375.

Egger, P., & Pfaffermayr, M. (2004). The impact of bilateral investment treaties on foreign direct investment. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32 (4), 788–804.

Elkins, Z., Guzman, A. T., & Simmons, B. A. (2006). Competing for capital: the diffusion of bilateral investment treaties, 1960–2000. International Organization, 60(4), 811–846.

Falvey, R., & Foster-McGregor, N. (2018). North-South foreign direct investment and bilateral investment treaties. The World Economy, 41(1), 2–28.

fDi Markets. (2019). The Financial Times Ltd. Available from www.fdimarkets.com.

Fisman, R. (2001). Estimating the value of political connections. American Economic Review, 91(4), 1095–1102.

Gertz, G. (2018). Commercial diplomacy and political risk. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 94–107.

Gilpin, R. (1987). The political economy of international relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84(4), 833–50.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Victor, D. G. (2016). Secrecy in international investment arbitration: an empirical analysis. Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 7(1), 161–182.

Haftel, Y. Z. (2010). Ratification counts: US investment treaties and FDI flows into developing countries. Review of International Political Economy, 17(2), 348–377.

Hallward-Driemeier, M. (2003). Do bilateral investment treaties attract foreign direct investment? Only a BIT and they could bite. The World Bank.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

Henisz, W. (2017). The political constraint index (polcon) dataset 2017 release. The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Hodgson, M. (2014). Counting the costs of investment treaty arbitration. Global Arbitration Review, 24.

Hogan, L. (2015). Risk and return-foreign direct investment and the rule of law. Hogan Lovells.

Jäger, K., & Kim, S. (2019). Examining political connections to study institutional change: evidence from two unexpected election outcomes in south korea. The World Economy, 42(4), 1152–1179.

Jensen, N. (2008). Political risk, democratic institutions, and foreign direct investment. The Journal of Politics, 70(4), 1040–1052.

John, T. S. (2018). The rise of investor-state arbitration: politics, law, and unintended consequences. London: Oxford University Press.

Kaskey, J. (2013). Dow chemical gets $2.19 billion for canceled Kuwait deal. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-05-07/dow-chemical-gets-2-2-billion-for-canceled-kuwait-deal. Accessed 12 November 2022.

Kerner, A. (2009). Why should I believe you? The costs and consequences of bilateral investment treaties. International Studies Quarterly, 53(1), 73–102.

Kerner, A., & Lawrence, J. (2014). What’s the risk? bilateral investment treaties, political risk and fixed capital accumulation. British Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 107–121.

Kim, I. S. (2018). Lobbyview: Firm-level lobbying & congressional bills database. Unpublished manuscript, MIT, Cambridge, MA http://webmitedu/insong/www/pdf/lobbyviewpdfGoogleScholarArticleLocation. Accessed 12 November 2022.

Krasner, S. D. (1978). Defending the national interest: Raw materials investments and US foreign policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Leeds, B., Ritter, J., Mitchell, S., & Long, A. (2002). Alliance treaty obligations and provisions, 1815-1944. International Interactions, 28(3), 237–260.

Lipson, C. (1985). Standing guard: Protecting foreign capital in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, vol 11. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Manger, M. S. (2012). Vertical trade specialization and the formation of North-South PTAs. World Politics, 64(4), 622–658.

Manger, M. S. (2009). Investing in protection: The politics of preferential trade agreements between North and South. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manger, M. S., & Peinhardt, C. (2017). Learning and the precision of international investment agreements. International Interactions, 43(6), 920–940.

Marshall, M. G., Jaggers, K., & Gurr, T. R. (2011). Polity IV project: political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800-2011. Center for systemic peace.

Maurer, N. (2013). The empire trap: the rise and fall of US intervention to protect American property overseas, 1893-2013. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Milner, H. (1988). Trading places: industries for free trade. World Politics, 40(3), 350–376.

Neumayer, E. (2006). Self-interest, foreign need, and good governance: are bilateral investment treaty programs similar to aid allocation?. Foreign Policy Analysis, 2(3), 245–267.

Neumayer, E., & Spess, L. (2005). Do bilateral investment treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries?. World Development, 33(10), 1567–1585.

Osgood, I. (2017). Industrial fragmentation over trade: the role of variation in global engagement. International Studies Quarterly, 61(3), 642–659.

Osgood, I., Tingley, D., Bernauer, T., Kim, I.S., Milner, H.V., & Spilker, G. (2017). The charmed life of superstar exporters: survey evidence on firms and trade policy. The Journal of Politics, 79(1), 133–152.

Owen, E. (2019). Foreign direct investment and elections: the impact of greenfield FDI on incumbent party reelection in Brazil. Comparative Political Studies, 52(4), 613–645.

Peinhardt, C., & Allee, T. (2012). Failure to deliver: the investment effects of US preferential economic agreements. The World Economy, 35(6), 757–783.

Pekkanen, S. M. (2008). Japan’s aggressive legalism: law and foreign trade politics beyond the WTO. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pelc, K. J. (2017). What explains the low success rate of investor-state disputes?. International Organization, 71(3), 559–583.

Peng, M. (2013). Global strategy. Cengage learning.

Prechel, H. (2006). Politics and Globalization, vol 15. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Raviv, A. (2015). 29 achieving a faster ICSID. In Reshaping the investor-state dispute settlement system. Brill Nijhoff, pp 653–717.

Reuters. (2015). Ecuador-occidental arbitration award reduced to $1 billion. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ecuador-occidental-idUSKCN0SR24V20151102. Accessed 12 November 2022.

Rose-Ackerman, S., & Tobin, J. (2005). Foreign direct investment and the business environment in developing countries: the impact of bilateral investment treaties.

STX Corporation. (2006). Minister of Azerbaijan visited STX. https://www.stx.co.kr/Eng/PR/stxnews_view.aspx?L=RU41&IDX=MTc40&P=26. Accessed 12 November 2022.

STX Corporation. (2007). President of Azerbaijan visited STX shipyard. https://www.stx.co.kr/Eng/PR/stxnews_view.aspx?L=RU41&IDX=MjAw0&P=25. Accessed 12 November 2022.

Salacuse, J. W., & Sullivan, N. P. (2005). Do BITs really work: an evaluation of bilateral investment treaties and their grand bargain. Harv Int’l LJ, 46, 67.

Shadlen, K. (2008). Globalisation, power and integration: the political economy of regional and bilateral trade agreements in the Americas. The Journal of Development Studies, 44(1), 1–20.

Simmons, B. A. (2014). Bargaining over BITs, arbitrating awards: the regime for protection and promotion of international investment. World Politics, 66(1), 12–46.

Skovgaard Poulsen, L. N. (2020). Beyond credible commitments:(investment) treaties as focal points. International Studies Quarterly, 64(1), 26–34.

Treisman, D. (2015). Income, democracy, and leader turnover. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 927–942.

UNCTAD. (2017). World investment report 2017: Investment and the digital economy. UN.

Van Harten, G., & Malysheuski, P. (2016). Who has benefited financially from investment treaty arbitration? An evaluation of the size and wealth of claimants. (January 11, 2016) Osgoode Legal Studies Research Paper (14).

Verdier, P. H., & Voeten, E. (2015). How does customary international law change? the case of state immunity. International Studies Quarterly, 59 (2), 209–222.

Vernon, R. (1971). Sovereignty at bay: the multinational spread of US enterprises. New York: Basic Books.

Yackee, J. W. (2010). Do bilateral investment treaties promote foreign direct investment-some hints from alternative evidence. Va J Int’l L, 51, 397.

Yueh, L. (2011). Enterprising China: Business, economic, and legal developments since 1979. London: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to my advisor, Todd Allee, for his invaluable guidance. I thank Timm Betz, Inho Choi, Yoonbin Ha, Rebecca Hann, Virginia Haufler, Kai Jäger, Brandon Ives, Scott Kastner, Andrew Kerner, Jaehyun Lee, Youngjoon Lee, Andrew Lugg, John McCauley, Helen Milner, Chungshik Moon, Felipe Munoz, William Reed, Jae Hyeok Shin, Jennifer Tobin, Kate Warnell, Dae-yeob Yoon and conference participants at the 2021 Yonjung Political Science Association meeting, and the 2018 International Studies Association, the 2019 Midwest Political Science Association and the 2020 American Political Science Association annual meetings for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

This work is supported by the research funds from the Robert H. Smith School of Business.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Axel Dreher

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s)& author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S. Protecting home: how firms’ investment plans affect the formation of bilateral investment treaties. Rev Int Organ 18, 667–692 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-023-09486-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-023-09486-4