Abstract

While scholars have argued that membership in Regional Organizations (ROs) can increase the likelihood of democratization, we see many autocratic regimes surviving in power albeit being members of several ROs. This article argues that this is the case because these regimes are often members in “Clubs of Autocrats” that supply material and ideational resources to strengthen domestic survival politics and shield members from external interference during moments of political turmoil. The argument is supported by survival analysis testing the effect of membership in autocratic ROs on regime survival between 1946 to 2010. It finds that membership in ROs composed of more autocratic member states does in fact raise the likelihood of regime survival by protecting incumbents against democratic challenges such as civil unrest or political dissent. However, autocratic RO membership does not help to prevent regime breakdown due to autocratic challenges like military coups, potentially because these types of threats are less likely to diffuse to other member states. The article thereby adds to our understanding of the limits of democratization and potential reverse effects of international cooperation, and contributes to the literature addressing interdependences of international and domestic politics in autocratic regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Scholars studying processes of democratization have long argued that membership in Regional Organizations (ROs) can increase the likelihood of democratic transitions (Ahlquist & Wibbels, 2012; Pevehouse, 2002a, b, 2005; Wright, 2009). However, many autocratic regimes seem to thrive in power albeit being members in a number of ROs including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), or the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) (Börzel & Risse, 2016a). Theoretically, the absence of democratization in these cases can be explained by missing scope conditions. Only liberalizing regimes are likely to profit from RO membership in terms of democratization because they strategically join ROs with a “democratic density” in order to tie the hands of future governments and receive assistance to consolidate democratic transitions (Fearon, 1997; Mansfield & Pevehouse, 2006, 2008; Martin, 1993, 2017).

But if this is the case, what do autocratic regimes get from membership in ROs? I argue that autocratic regimes profit from membership in “Clubs of Autocrats”, that is, ROs that are composed of more autocratic regimes, because they can increase the likelihood of autocratic regime survival. Autocratic RO membership can alleviate future uncertainty in two important ways. First, it helps to protect from unwanted external interference from other RO member states, particularly during moments of political turmoil, by institutionalizing norms of sovereignty and non-interference into politically central arenas of power. Second, it offers additional material and immaterial resources that can help autocratic incumbents to boost domestic survival strategies vis-à-vis domestic challengers such as legitimation, repression and co-optation. Therefore, autocratic regimes may be willing to bear some limited sovereignty costs resulting from formal cooperation in exchange for increased regime security.

To support this argument, I assemble original data on membership of 120 autocratic regimes in 70 ROs between 1946 to 2010. Based on survival analysis, I examine to what extent membership in autocratic ROs is related to higher likelihoods of regime survival when controlling for alternative domestic politics and geopolitical explanations. I find that membership in ROs with a higher autocratic density does indeed prolong time in power for autocratic incumbent regimes. However, RO membership only seems to protect from democratic challenges such as large-scale public demonstrations or oppositional dissent that aim to change the fundamental state-society relations of a regime. In contrast, membership in an autocrat’s club does not help to prevent successful autocratic challenges such as military coups that only aim to replace the current autocratic leader without changing underlying power distributions. This might potentially be the case because the theorized mechanisms only work if the threat to one regime has a high likelihood of diffusing to all member states. While this is often the case with public protest (Brinks & Coppedge, 2006), autocratic challenges differ profoundly between different types of autocratic regimes (Geddes, 1999) and will therefore be much less likely to spread and threaten all RO members.

The article ties in with recent scholarship that investigates if and how international cooperation between authoritarian regimes helps autocratic incumbents resist democratization (Debre 2021; Tansey, 2016a; von Soest, 2015). Scholars highlight that autocratic regimes exploit ROs for “regime-boosting” (Söderbaum, 2004), that is, to strengthen regime stability by consolidating national sovereignty (Acharya, 2016; Acharya & Johnston, 2007), legitimizing regimes domestically (Debre, 2020; Libman & Obydenkova, 2018; Yom, 2014), engaging in rent-seeking activities to buy the loyalty of crony elites (Herbst, 2007) or to pursue cross-border policing (Cooley & Heathershaw, 2017). Findings from anti-corruption research also show that the company states keep is highly consequential, with institutions made up of mostly corrupt donors being much less likely to enforce anti-corruption mandates, even though they might adopt them in the first place to conform to global norms of good governance (Ferry et al. 2020; Hafner-Burton & Schneider, 2019).

However, much of the literature on the dark side of regional cooperation still lacks sufficient theorization on the conditions under which RO membership benefits autocratic regime survival, as well as systematic quantitative cross-case analysis on domestic effects of RO membership. Instead, much of the work on autocratic regime-boosting focuses on single case studies of regimes or regions (Allison, 2008; Debre, 2020; Barnett & Solingen, 2007; Börzel & van Hüllen, 2015; Collins, 2009; Herbst, 2007). While these qualitative works are important contributions that identify underlying mechanisms, this contribution provides generalizable evidence to show under which conditions RO membership is beneficial for autocratic regime survival. Where scholars do engage in cross-case hypothesis testing (Libman & Obydenkova, 2013; Obydenkova & Libman, 2019), they investigate a different dependent variable and explain why autocratic regimes join ROs. Instead, I focus on domestic consequences of membership for autocratic survival.

The article proceeds in four steps. I first outline how membership in an autocrats’ club can influence autocratic regime survival by protecting members from external interference and supporting domestic survival strategies with additional material and ideational resources. In a second step, I then hypothesize about conditions under which RO membership is likely to produce regime-boosting effects. Third, I present the results from survival analysis to show that membership in more autocratic ROs is indeed connected to higher likelihoods of preventing democratic regime change. In a fourth concluding section, I discuss the theoretical implications of these findings for the research agenda on the international dimension of authoritarian resilience and comparative regionalism, as well as consequences for future research on institutional design of IGOs.

2 Regional organizations and authoritarian survival

2.1 Domestic effects of RO membership

Institutionalist international relations (IR) theory locates the demand for formalized cooperation on the systemic level, arguing that IGOs help member states to solve cross-border issues (Abbott & Snidal, 1998; Keohane, 1984) or that they serve to further a hegemon’s international interest (Gilpin, 1981; Ikenberry, 2001). In contrast, approaches that explicitly incorporate domestic politics to explain the demand to form and join IGOs argue that foreign policy preferences of states are driven by “two-level games” (Putnam, 1988): governments try to cater to domestic coalitions by creating IGOs. This argument has been particularly taken up by the IR literature on democratization, arguing that IGOs and particularly ROs can help liberalizing member states to credibly commit to certain policies domestically (Moravcsik, 2000). Since liberalizing regimes usually face high uncertainty regarding the credibility of their reform efforts during democratic transitions, they can join democratic ROs to signal to domestic audiences that they are committed to democratization (Fearon, 1997; Mansfield & Pevehouse, 2006, 2008; Martin, 1993). Furthermore, newly established democracies also benefit from membership in the long run, because external monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms tie the hands of future governments and prevent policy reversals (Martin, 2017; Pevehouse, 2002b, 2005).

Both systemic and domestic accounts mostly disregard the question of regime type. For systemic theorists, interdependencies drive cooperation, and the question if autocracies and democracies might be equally willing and able to commit to formal cooperation is left untouched. However, due to informal and nontransparent politics, autocracies are considered to differ to democracies “in terms of their mutual suspicions and divergences, and inherent difficulties in working together as voluntary and mutually trusting partners” (Whitehead, 2014, p. 23). Autocracies might thus be perceived as more likely to renege on their international commitments by democratic counterparts, which could impinge on the likelihood of cooperation even in case of high interdependencies and potential mutual gains. Domestic politics accounts, in contrast, only theorize why joining IGOs might be beneficial for democratic and liberalizing regimes without specifically addressing how autocracies might benefit domestically from RO membership.

So why would autocratic regimes set-up or join ROs and delegate some limited authority to the supra-national level? The literature on regime-boosting argues that the demand to participate in ROs is driven by domestic survival politics of autocratic incumbent elites that hope to increase the likelihood of remaining in power by joining a “Club of Autocrats” (Libman & Obydenkova, 2013; Söderbaum, 2004; Debre, 2021). Autocratic RO membership offers the potential to strengthen legitimation strategies (Libman & Obydenkova, 2018; Russo & Stoddard, 2018; Debre & Morgenbesser, 2017), to pursue dissidents across borders (Cooley & Heathershaw, 2017), to engage in rent-seeking activities (Collins, 2009; Herbst, 2007), or to feign commitment to global standards of good governance to international partners (Jetschke, 2015; van Hüllen, 2015).

To what extent and under which conditions autocracies actually profit from their RO membership in terms of increasing domestic survival chances, however, remains unclear. I argue that two mechanisms can explain domestic effects of RO membership. Autocracies are inherently threatened by domestic forces in the form of popular upheavals, oppositional actors or intra-elite coalitions that intend to challenge the current power distribution (Svolik, 2012), and therefore develop appropriate domestic survival strategies to mitigate these threats (Gerschewski, 2013). However, to increase the likelihood of success for survival politics during times of political upheaval, autocratic regimes might want secure additional regional support through RO membership by both regulating behavior with like-minded international allies to shield themselves from unwanted external interference as well as gaining access to additional regional resources.

First, RO membership helps autocratic regimes to regulate behavior between neighboring states, and profit from institutionalized norms of sovereignty protection and non-interference. From a historical perspective, institution-building in much of the non-democratic Global South was a post-colonial nation-building exercise (Acharya, 2016). Many ROs such as the Arab League, the Association of South-East Asian Nations, or the Organization of African Unity were specifically designed to foster sovereignty and non-interference, thereby alleviating the perceived threat to independence for newly created post-colonial states (Acharya & Johnston, 2007). Until today, autocratic regimes remain highly sensitive to interventionist politics due to the rise of global norms such as election monitoring, the responsibility to protect, or democracy-protection sanctions that increase the cost of authoritarian survival strategies such as repression or electoral fraud. RO membership can thus be seen as a way to profit from these institutionalized norms and ensure that neighboring regimes will not come down on the side of domestic challengers during political turmoil.

Sovereignty, in this regard, has to be understood in non-absolute terms that allow for a differentiated perspective on governing power. States commonly delegate decision-making competences to international bodies in some specific policy area, while retaining sovereignty rights in others. Alan Milward (1992), for instance, argued that integration in Europe has mostly taken place within ‘low politics’ that are not essential to political sovereignty issues of ‘high politics.’ Therefore, post-war European states were essentially willing to give up limited areas of sovereignty in economics and trade to “rescue” the European nation state system. Likewise, autocracies might agree to coordinate with neighboring regimes in certain policy areas and accept some restrictions of their decision-making freedom in exchange for the protection of core political sovereignty rights such as the use of force or conduct of elections. Institutionalized norms of non-interference within ROs then help to expand the room to maneuver against political challengers because autocratic regimes can exercise costly survival strategies without the danger of external interference by neighboring states (see Tansey, 2016a on this point for autocratic sponsorship by autocratic regional powers). Consequently, autocracies might be willing to accept some limitations to sovereign decision-making vis-à-vis neighboring states that come with membership in ROs in exchange for ensuring non-interference into politically sensitive areas during uncertain moments.

Second, RO membership can also be a means to secure access to pooled regional resources to mitigate domestic challengers during moments of uncertainty. ROs can essentially be conceived as opportunity structures that pool and provide additional resources to empower some domestic actors over others (Börzel & Risse, 2003). RO membership thus opens access to both material resources such as financial redistributions, market access, military equipment, intelligence sharing, or technical support, but also to ideational support such as diplomacy or regional identity discourses. During moments of political turmoil, these additional resources can make a substantial difference to tip the scale in favor of autocratic incumbents. In contrast to short-lived alliances or bilateral relations, formalizing these pooling measures within a RO represents a higher level of commitment to support the existing non-democratic status-quo amongst member states in times of political turmoil.

Regionally pooled resources can essentially be used to strengthen three main survival strategies commonly employed by autocratic incumbent regimes: legitimation, co-optation, and repression (Debre, 2021). While these three strategies can exert mutually reinforcing effects, their respective application and combination often varies depending on type of regime and threat (Gerschewski, 2013). First, ROs can generate legitimacy by helping regimes to present themselves as democratic and part of a regional ideational group. Legitimacy in autocratic regimes either rests on presenting incumbents as quasi-democratic or by recurring to alternative legitimation strategies based on traditional values or ideology (Dukalskis & Gerschewski, 2017; von Soest & Grauvogel, 2017). RO “shadow election monitoring” (Kelley, 2012) has emerged as a highly effective way to award autocratic incumbents international recognition for highly flawed elections by praising their democratic quality without actually engaging in meaningful monitoring activities (Debre & Morgenbesser, 2017). Additionally, ROs often represent ideational communities with common value systems such as Eurasianism in the post-Soviet space (Laruelle, 2008), the “ASEAN Way” in Southeast Asia (Acharya, 2003), pan-Arabism in the Middle East (Korany, 1986), or the Shanghai Spirit in Central Asia (Ambrosio, 2008). By drawing on those regional values and identities, autocratic incumbents strengthen alternative domestic legitimation narratives while critical actors are cast as part of an illegitimate out-group (Hellquist, 2015, Debre, 2020).

Second, ROs provide material benefits in the form of economic support, financial redistributions and development aid or bureaucratic positions that can be employed to strengthen the co-optation of key elites. The literature on regionalism in Sub-Saharan Africa shows how ROs help to sustain patrimonial networks by accumulating diplomatic positions to reward politicians, business elites and military personnel with reputable jobs and to capture rents such as tariff revenues by undermining trade liberalization (Bach, 2005; Hartmann, 2016; Herbst, 2007). Additionally, development assistance, especially from new South-South donors is of particular interest to authoritarian regimes to increase rent-seeking capacities, especially given the fact that all types of development assistance are often intentionally or unintentionally blind to regime type and can thus be easily exploited (Bruszt & Palestini, 2016; Kararach, 2014; Kono & Montinola, 2013). Even the suggestion of economic regionalism without meaningful liberalization might be enough in the short-term ensure the loyalty of key business elites (Collins, 2009).

Third, regional security cooperation and intelligence sharing may help to boost the repression of popular uprisings and oppositional actors. Many ROs such as the Economic Community of West African States or ASEAN have developed security capacities over time, or have been specifically founded as security institutions, such as the SCO. Autocratic regimes might be particularly interested in increased intelligence cooperation. In Central Asia for instance, the SCO Regional Antiterrorism Structure has played a major role in helping member states to criminalize legitimate opposition by blacklisting, extradition, and denial of asylum for political opposition (Cooley & Heathershaw, 2017). Similarly, cross-border policing has become a popular instrument among GCC members to better pursue and prosecute critical activists independently of their physical location (Yom, 2016). While military interference to safeguard an incumbent regime comparable to the 2011 GCC intervention in Bahrain remains the exception, joint military maneuvers can still be used to signal military strength to potential challengers. Finally, simply having the opportunity to learn from other incumbent regimes about “worst-practices” within an institutionalized setting with regard to crisis management can strengthen successful repressive strategies (Yom, 2014).

2.2 The supply and design of institutional cooperation between autocracies

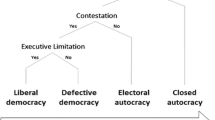

Not all IGOs will be likely to supply autocratic incumbents with the functions outlined above. A central part of this argument comprises the two expectations that first, only “Clubs of Autocrats” as well as second, ROs with low authority levels will be likely to supply those mechanisms. First, I hypothesize that ROs with a higher “autocratic density” – that is, ROs composed of more autocratic member states, should theoretically be more likely to provide the expected stabilizing benefits. I thus adopt a gradual understanding of regime type which is defined as a continuum between full democracy and closed autocracy, and expect that ROs with more autocratic membership will also produce a stronger effect on the likelihood of survival.

I follow rational-institutionalist assumptions that states employ international institutions to further their strategic and normative domestic preferences, and that cooperation will be easier with other states that share similar preferences (Hall & Taylor, 1996). I also contend that political survival is a common preference of all regime types, but that strategies to achieve survival differ significantly between democracies and autocracies, also with regard to their foreign policy choices (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003; Weeks, 2008). Democracies need to cater to a wider selectorate and therefore have to provide common goods to a large numbers of citizens to achieve reelection, while also promoting and protecting free and fair elections, the rule of law, and civil liberties at home and abroad (Bermeo, 2016; Lührmann & Lindberg, 2019). Liberalizing regimes are particularly often challenged by disenfranchised autocratic elites that aim to reverse reforms and regain control and therefore look for support to consolidate democracy (Moravcsik, 2000). Autocracies, in contrast, cater to a much smaller group of politically and economically relevant elites, and are thus better off providing club goods to ensure the loyalty of the winning coalition, while repressing dissidents and public protestors that aim to topple the current regime (Geddes et al. 2018; Gerschewski, 2013; Svolik, 2012).

Consequently, the composition of membership of an institution in terms of regime type is an important dimension to determine the outcomes of cooperation. Democracies and liberalizing regimes should be more likely to employ ROs to jointly provide common goods to their selectorates, to spread and protect norms of good governance and human rights, and to funnel resources to liberal coalitions to assist them in consolidating democratic transitions. In contrast, autocracies should have higher preferences to employ institutions to redistribute resources that help to strengthen autocratic incumbent elites vis-à-vis domestic challengers, and to protect regimes from external pressure to democratize.

In fact, previous research shows that ROs that are dominated by more democratic members are more often equipped with enforceable democracy and conditionality clauses as well as judicial control mechanisms that can provide for credible commitments and constrain future reversals of democratic reform in member states (Pevehouse, 2005, 2016; Schimmelfennig, 2016). Efforts to redistribute resources towards liberal elites have also been a central goal of EU accession and neighborhood policy (Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, 2005), while democratic coalitions have used IGOs and bilateral and multilateral trade-agreements to spread human rights and good governance provisions (Greenhill, 2015; Hafner-Burton, 2009). International donor organizations comprised of member states with lower levels of corruption are also more likely to adopt and enforce anti-corruption standards and refrain from diverting money to corrupt states (Ferry et al. 2020; Hafner-Burton & Schneider, 2019).

Second, the above argument also implies that ROs with a weak institutional design that remains in the realm of intergovernmental cooperation should be more likely to provide benefits to autocratic regime survival. Since autocrats want to gain additional support and prevent unwanted external interference through RO membership, they are aware of possible unintended consequences resulting from entering into legally binding forms of cooperation. Thus, they will try to avoid such consequences by making specific institutional design choices to hold tight on the reins of power without delegating too much enforcement competences to RO bureaucracies or installing majority voting procedures. RO bureaucracies with agenda-setting or enforcement powers, for instance in the form of regional courts, might in fact punish member states for employing autocratic survival strategies and thus increase the costs of repressive and manipulative tactics (e.g. Alter & Hooghe, 2016; Jetschke & Katada, 2016). When the newly established SADC court ruled against the Zimbabwe regime on grounds of human rights protection, the tribunal was quickly banished because it interfered too heavily with the domestic politics of the Mugabe regime (Hulse & van der Vleuten, 2015). In a similar vein, empowered bureaucrats with agenda-setting power might push for the adoption of stricter democratic regional standards or block the redistribution of resources to regimes that have come under political pressure. Thus, ROs with weaker institutional designs should be more likely to serve autocratic member states during political turmoil and help them stay in power.

Findings from recent research on international authority for instance show that many autocratic ROs in the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Central and Southeast Asia are equipped with less authority, particularly with regard to pooled decision-making procedures compared to democratic ROs in the Global North like the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe (CoE), or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) (Hooghe et al. 2017, 2019b). Furthermore, for many of these autocratic ROs, sovereignty protection is a major driver to explain shallow institutional design including informal and consensual forms of decision-making and strong norms protecting sovereignty and non-interference: “One common feature of these regional “ways” is that notwithstanding geographic, cultural, and political differences and the time lag in their evolution, the emphasis on sovereignty and non-interference has remained a powerful constant” (Acharya & Johnston, 2007, p. 246).

I also follow recent scholarship on the international dimension of authoritarian resilience and argue that authoritarian regimes are mostly concerned with preventing regime change, not with promoting authoritarianism as a regime type abroad (Tansey, 2016b; von Soest, 2015; Way, 2015). Consequently, RO membership is assumed to produce a stabilizing effect for regimes, because the mechanisms outlined above are mostly employed during crisis situation when the survival of regimes is in jeopardy. This also builds on democratization literature that has mostly argued that IO membership helps to stabilize newly established democracies by tying hands of future elites that might want to reverse democratic reform efforts, but that membership does not induce regime change (Pevehouse, 2005).

Finally, I restrict the analysis to regional IGOs because I expect that the hypothesized effects should play out particularly within ROs instead of global IGOs. ROs consist of geographically and culturally proximate members, and can thus be particularly well employed to further domestic preferences without the confounding influence of international-level dynamics. ROs tend to be community-oriented, involving fewer numbers and more interaction compared to task-specific and universal membership IGOs that deal with global coordination problems (Hooghe et al. 2019b). Thus, ROs are also closer to domestic and regional political events, so the proposed causal processes should work more easily.

3 Testing the argument

3.1 Unit of analysis, sampling, and statistical model

The above argument suggests that there should be a strong relationship between membership in a more autocratic RO and regime survival. To test this relationship, I conduct survival analysis using an original dataset that includes data on the membership of 120 autocratic regimes in a sample of 70 ROs between 1946 to 2010. The unit of analysis is country-year, with a data point for every autocratic country year of independent states with more than one million inhabitants between 1946 to 2010 as coded by the Geddes, Wright and Frantz dataset “Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions” (Geddes et al. 2014).

For each year, I code membership of all 120 regimes included in the dataset by Geddes et al. (2014) for a sample of 70 current and dead ROs that were founded between 1945 and 2010.Footnote 1 Sampling of ROs is based on the Yearbook of International Organizations (YIO), whereby ROs are defined as the formal and institutionalized cooperative relations among at least three states within a region (Börzel & Risse, 2016b). Accordingly, all IGOs listed in the YIO with (1) regionally defined membership, (2) at least three member states, and (3) a formal secretariat, are included. Additionally, only ROs that comprise political and/or security as policy fields are selected because the theorized mechanisms cannot work in purely task-specific technical ROs that do not cover matters of high politics. Policy fields of ROs were coded based on the RO profiles in YIO. A list of all ROs covered by the dataset can be found in Table A11 in the annex.

To estimate effects, I employ survival analysis (Cox, 1972), which is a particularly well-suited set of methods to analyze the time until the occurrence of an event, in this case, the breakdown of autocratic rule. Essentially, survival models estimate how covariates change the underlying baseline hazard of an event occurring at time t, given that the subject under analysis has survived until this point in time. The models are advantageous to deal with issues of right-censoring, which is important since countries are only observed until 2010, but may not have experienced a breakdown event until that point of time.

Countries enter the risk set with the first autocratic year and exit the year after a breakdown event with countries that are still autocratic at the end of the study period in 2010 as right-censored. Since countries can theoretically undergo several instances of regime change and backsliding over time, the data is in multiple failure-time format, with countries that experience re-autocratization entering the risk-set again the year after the event. In total, 22 out of 120 autocratic regimes re-enter the dataset at some point after previously undergoing democratic regime change, with 9 out of those 22 experiencing more than one instance of re-autocratization (amongst those, Haiti, Peru and Thailand as the least stable regimes with three instances of re-autocratization each). In total, the dataset includes 101 cases of democratic regime change and 111 cases of autocratic replacement for the study period 1946–2020.

I estimate stratified Cox proportional hazard modelsFootnote 2 with robust standard errors following a conditional risk set approach (Prentice et al. 1981). The models work with random hazard functions based on time since study entry, and stratify units on the number of preceding failure events. This approach is chosen to account for multiple ordered failure events. First, failures are assumed to be ordered since countries are not at risk of a second failure event if they have not experienced a preceding moment of breakdown. Second, countries are stratified by number of preceding failure events, since a country that has previously undergone a breakdown should theoretically have a different underlying hazard of experiencing a recurring failure compared to countries that have been stable over longer time periods without any failure events. Finally, time is counted from the first time a country enters the risk set to account for the overall time a country has been under autocratic rule. As robustness check, models without stratification and models counting time from previous failure events are estimated and reported in the online appendix.

3.2 Dependent variable: Autocratic and democratic regime breakdown

The dependent variable measures two types of breakdown events that can end the survival spell of an autocratic regime: autocratic regime breakdown due to autocratic replacements (autrep), and autocratic system breakdown due to democratization (democ). Autocratic replacements refer to transitions from one type of autocratic regime to a different type of autocratic regime (e.g. a change from monarchical to military rule after a successful coup), while democratization refers to system breakdowns leading to subsequent democracy. To measure both types of outcomes, I take the binary variables on transitions from Geddes et al. (2014).

Autocratic replacements have only recently been included into the study of stability and survival, while previous analyses have mostly dealt with democratization. However, separating both types of breakdowns makes a big difference when analyzing drivers of survival because it helps to separate if and how predictor variables help to deter against replacements by a rivaling autocratic group or against democratic challengers, and can thus offer more fine-grained information on underlying processes. The influence of resource wealth on authoritarian survival has for instance been a topic of debate for years, with some authors arguing that it does destabilize autocracies (Ross, 2001, 2012), while others could not find negative effects on autocratic survival (Haber & Menaldo, 2011). However, when separating both types of regime breakdowns, analysis shows that resource wealth does in fact have a positive effect on survival by lowering the likelihood of replacements by a rivaling autocratic group, but that resources do not help to deter democratic challengers to prevent democratization (Wright et al., 2015).

3.3 Independent variables

I construct two variables to test the argument that membership in a more autocratic but less authoritative RO should increase the probability of authoritarian regime survival. The first independent variable, autocratic density (autdensity), represents the average autocracy score of the most autocratic RO in which state i is a member based on the Polity IV data (Marshall et al. 2016).Footnote 3 The measure is constructed by computing the average polity2 score of all member states of a RO in which country i is a member in year t, without the score for country i. The final score for each country i is achieved by transforming the polity2 score so that the final range runs from 1 (highly democratic) to 21 (highly autocratic), with 0 signaling no membership. ROs with a score of 6 and higher are consequently considered as autocratic, including the category of anocracies. I expect that membership in more autocratic ROs should reduce the probability of both types of breakdown events, and that the effect is more pronounced the higher the autocratic density of an RO. However, autocracies could be members in an additional RO that is comprised of more democratic members and thus might counteract the effects of the autocratic RO membership, thereby biasing estimation results. To account for possible changes in density scores across all RO memberships, I also test if results remain similar when including the average density across all RO memberships (avgdensity).

The second independent variable measures the authority of a RO proxied by the degree of delegation awarded to regional courts.Footnote 4 The presence of a regional court has been argued to be a major international driver of democratization processes because they can sanction non-compliant member states and thereby empower democratic coalitions over autocratic elites (Alter, 2014; Alter & Hooghe, 2016; Lenz & Marks, 2016, p. 526; Moravcsik, 2000). In contrast, ROs without a regional court have no enforcement capacity over member states, thereby protecting them from interference in domestic politics (Hancock & Libman, 2016; Jetschke & Katada, 2016) and enabling exploitation of RO bureaucracies for patronage politics (Gray, 2015; Herbst, 2007). I include a binary variable that measures if the RO under investigation has a permanent, non-obligatory regional court with some binding authority over human rights and good governance matters (authority). In a first step, ROs with a permanent court were identified based on the variable dispute settlement taken from Hooghe et al. (2017) and ROs with a court coded as 1. Those ROs not covered by the Hooghe et al. dataset were coded based on the collection of RO courts in Alter (Alter, 2014) and Alter and Hooghe (Alter & Hooghe, 2016) and further supplemented by an online search on the respective RO website for all those ROs covered in the sample of this study that are not included in either of those works. I expect that membership in ROs without a regional court should increase the probability of both types of breakdown events.

To control for alternative explanations, I further include predictor variables pertaining to international and domestic level arguments from the IR and comparative authoritarianism literature. First, power-based approaches from the IR literature such as hegemonic stability theory suggest that regional institutions are only epiphenomenal to the underlying power asymmetries within a region (Gilpin, 1987). States thus join international institutions such as ROs to bandwagon with regional powerhouses that wield substantial economic and military power and are willing to act as the “regional paymaster” (Mattli, 1999, p. 5). To assess if survival is more likely where an autocratic power dominates a region, I include a variable to test for the effect of regional power asymmetries (hegemon). I understand a regional autocratic power as the state with the highest share of material capabilities in a region, with at least 20% of all regional power capabilities based on the COW National Material Capabilities dataset (Singer, 1988). The variable is a dummy coded 1 if country i is a member of a RO with any of the regional powers as members. A further realist implication flows from balance-of-power theory, which argues that international anarchy results in internal and external balancing to protect states from aggression by a dominant power (Waltz, 1979). Since balance-of-power should lead to a stable international system, I would expect higher likelihoods of breakdowns with the end of the Cold War. To capture this change in the international system, I include a dummy variable (coldwar), coded 0 before 1990 and 1 afterwards.

Contagion offers a second international alternative to explain regime dynamics. Diffusion approaches treat events such as regime transitions as open to interdependent decision-making rather than purely endogenous or functional processes of rational actors (Gleditsch & Ward, 2006; Risse, 2016). These interdependencies play out particularly strongly on the regional level as waves of regime breakdowns such as the Color Revolutions or the Arab Spring have shown. To control for these types of interdependencies, I include a binary indicator coded 1 if a state in the region has experienced a democratic regime change (for the dependent variable democratization) or autocratic breakdown (for the dependent variable autocratic replacements) in the previous year.

To control for alternative explanations identified by the comparative authoritarian resilience literature, I include three further variables pertaining to domestic-level factors. First, the institutionalist literature argues that institutional variation between regimes can account for differences in survival (Brownlee, 2007; Gandhi, 2008; Geddes, 1999; Hadenius & Teorell, 2007). In essence, this literature finds that regimes with institutionalized dominant parties and legislatures are more stable because they constrain actors by containing conflict amongst elites, and by binding them to citizens through established patronage networks (Pepinsky, 2014). To capture the effect of regime type on survival, I include a categorical variable based on the definition of regime type in the Geddes, Wright and Frantz dataset that codes each regime as either military, personal, party-based, or monarchy.

Second, both economic growth and economic crisis have been identified as important factors to survival and breakdown of autocracies and democracies, although the literature is divided on the direction and causality of the relationship (Cheibub & Vreeland, 2011). While modernization theory argues that economic wealth can induce democratic regime transitions (Gasiorowski, 1995; Lipset, 1959), its critics posit that economic growth rather stabilizes autocratic systems (Huntington, 2006; Moore, 1966; O’Donnell, 1973) or that the relationship is dynamic and dependent on degree of growth (Przeworski et al., 2000). To control for the possible effect of economic growth on regime survival, I include annual growth rates (growth) based on logged GDP per capita taken from Maddison (Maddison, 2010).

Finally, structural factors, most importantly resource wealth, have been argued to produce positive effects for autocratic survival. The literature on rentier state theory argues that governments reliant on external revenue from natural resources can act more autonomously from society since they are not dependent on taxation (Beblawi & Luciani, 1987; Mahdavi, 1970). Instead, rentier states can offer benefits and sustain coercive institutions to alleviate pressure for democratization (Ross, 2001). I include total resource income per capita (resources) taken from Haber and Menaldo (2011) with the expectation that rising levels of resource wealth make autocratic replacements more likely, but do not significantly affect the likelihood of democratization (Wright et al. 2015).

3.4 Statistical results

Before investigating results from the Cox regression analysis, it is helpful to look at the baseline survival rates of democratization and autocratic replacements using the Kaplan–Meier estimator. For both democratization and autocratic replacements, regimes are relatively volatile for about 50 years, with median survival times at about 40 until democratization and 30 until autocratic replacements (see Fig. 1). However, some regimes manage to survive exceptionally long without undergoing any form of breakdown event. Amongst those are regimes such as Mexico (85 years until democratization), South Africa (84 years until democratization), Ethiopia (85 years until autocratic replacement), Nepal (105 years until autocratic replacement), and Saudi Arabia (83 years of uninterrupted rule until 2010).Footnote 5

Table 1 presents results of the estimated models. Column one presents results for the dependent variable democratization and column two for autocratic replacements. Overall, Table 1 reveals important insights about the effect of international-level factors on survival. Across time and space, membership in ROs with higher autocratic density significantly reduces the hazard of experiencing democratic breakdowns, but does not seem to protect from autocratic replacements. Thus, membership in more autocratic ROs produces a system-boosting effect: it protects from democratic challengers aiming for a larger systemic change in the underlying power distributions between ruler and ruled, while not protecting from autocratic challengers that aim to change the power distribution within the ruling elite. This effect on authoritarian survival also remains the same when including the average density across all RO memberships, indicating that autocratic regimes rarely seem to be members in both very autocratic and democratic ROs (see Online Appendix, Table 6).

It is of course possible that the estimated effect of autocratic density is not due to membership in the organization, but rather due to diffusion between neighboring states. While the models do control for contagion of breakdown events, they might omit controlling for other forms of bilateral diffusion. To mitigate this potential omitted variable bias, I add a variable capturing the percentage of autocracies in a region (diffusion_regional). The results are reported in Table A1 in the annex. The variable does not achieve significance in both models, while autocratic density remains significant, although at a slightly lower significance level. This seems to suggest that the effect of autocratic density on survival is due to something related to RO membership and not just a matter of regional diffusion.

Most other international-level factors do not achieve significance and thus do not seem to effect the hazard of survival in a meaningful way.Footnote 6 Only contagion is significantly related to autocratic replacements, however in a surprising way. Previous experiences of autocratic replacements in regionally proximate states actually decrease the hazard of experiencing a similar event over time. This might point to learning effects stressed by the recent literature on authoritarian collaboration, whereby late-risers during waves of instability might learn from earlier examples, and adapt their strategies accordingly to prevent breakdowns (Ambrosio, 2010; Bank & Edel, 2015; Vanderhill, 2013).

Domestic explanations stay mostly in line with previous research. Regime type is significantly related particularly to democratization, with party-based regimes (omitted category) as the most stable regime type and military regimes as the least stable category due to the fact that they carry inherent instabilities which will eventually lead to elite split (Geddes, 1999; Hadenius & Teorell, 2007). Finally, monarchies seem to remain even more stable than party-based regimes with regard to the potential for democratic regime change. This effect, however, is not stable across different model specifications (see Online Appendix) which can be due to the relatively low number of cases in the overall population.

Finally, growth significantly reduces the hazard both of experiencing democratic regime change and autocratic replacements, while resources do not seem to have a significant effect on the hazard of democratization. As previously argued, resource wealth can help to protect regimes from autocratic challengers, because oil wealth increases security spending and can thus shield regimes more effectively from military coups (Wright et al., 2015). These results speak for the necessity for differentiation in the dependent variable, because predictors may only initiate some forms of political mechanisms that cannot explain all forms of regime survival.

3.5 Robustness tests

To test the robustness of results, several follow-up tests were performed. First, I varied model specifications to check if results hold when changing the composition of risk sets with each failure event. Table A2 (Online Appendix) reports results from a conditional risk set approach that stratifies on number of failure events, but resets time at every failure. Table A3 (Online Appendix) reports results from a simple counting approach, whereby failure events are essentially treated as equal, so the risk set under analysis for a breakdown event k are all subjects under analysis at time t. In both cases, most results are not altered significantly. The only difference is that Cold War turns significant for both democratization and autocratic replacements, but in opposite directions. While the hazard of democratization increases significantly with the end of the Cold War, the risk of autocratic replacements decreases. The first result makes sense given that the third wave of democratization was initiated with the end of the Cold War. The increased stability of autocratic incumbents vis-à-vis autocratic challengers might be due to the fact that many autocratic regimes have transformed towards electoral party-based regimes under the rise of democratic elections as an international norm. Party-based regimes remain amongst the most stable regime category, while the numbers of military regimes and with it the most important category of autocratic replacements in the form of coups have decreased since 1990.

Second, I control for region-specific effects to ensure that results are not driven by significant differences between regions (Table A4, Online Appendix). Including regional dummies does not alter the results in significant ways and suggests that estimates are not affected by heterogeneity between regions. Third I control if results hold when employing alternative measurements to the polity variable. I construct the density variable based on the v2x_polyarchy variable in the Varieties of Democracy v. 10 dataset (Coppedge et al., 2020) and find that results remain robust to this alternative variable measurement (Table A7, Online Appendix). Forth, I exchange the main predictor variable Autocratic Density with an alternative variable measuring the number of autocratic RO memberships of a regime (overlap). The comparative regionalism literature has argued that many ROs are essentially dysfunctional paper tigers that are only set-up to prevent pressure for policy implementation in favor of purely rhetorical forms of regionalism (Allison, 2008; Söderbaum, 2011). By creating competing and overlapping regional agendas, regimes hope to appease national constituencies and reinforce national sovereignty over external agendas of democracy promotion. However, if our theory is correct, only membership in one highly autocratic RO is necessary to achieve desired results. Neither exchanging Overlap for Autocratic Density, nor adding it to the model changes results significantly (see Table A5, Online Appendix), which suggests that it is important to be a member in a highly autocratic RO, and not all ROs will be willing or able to serve as a conduit for enhanced stability.

Finally, I check if results change when weighing ROs according to their aggregate GDP to control for variation in economic power of institutions. While two ROs such as the SCO and the Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries (CEPGL) have similar autocratic density levels over time, the SCO with economically powerful member states Russia and China should be able to provide more financial resources and assurances compared to CEPGL’s small membership. Including a logged variable that measures the yearly aggregate total per capita GDP of all members divided by the number of RO member states does not achieve significance (see Table A8, Online Appendix). This could indicate that financial redistributions are not necessarily the most important causal factor explaining survival, but that regimes might rather profit from non-material resources such as diplomatic support and legitimation. This also ties to previous literature that shows the importance of regionally supplemented legitimation strategies as an important benefit of RO membership (e.g. Söderbaum, 2004; Libman & Obydenkova, 2018).

4 Discussion

Several of these results require further discussion. First, it is interesting to note that both specifications of the main variable Autocratic Density, the autocratic density score of the highest RO membership as well as the average density score across all ROs, both significantly reduce the hazard of democratic regime change. This points to sorting effects of RO membership, with autocratic regimes mostly joining “Clubs of Autocrats” instead of a mix of ROs with democratic and autocratic membership. This finding makes sense in light of Pevehouse (2005), who finds that newly democratizing regimes tend to join ROs with a democratic density to signal their commitment to domestic regime change to domestic and international audiences and consequently profit from their membership by stabilizing democratic governance. While some autocratic regimes are also members in ROs with a democratic density (e.g. Russia and previously the Soviet Union in the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe), membership in the opposite club is unlikely to induce regime change.

A second important finding is that membership in more autocratic ROs is the most significant international-level predictor to explain regime survival. The finding highlights the importance of studying cooperation between authoritarian regimes, as well as arguments by the regime-boosting literature that autocracies profit from RO membership in terms of strengthened regime security and prolonged survival. In fact, being a member in a highly autocratic RO (one standard deviation above the mean density score of 11) increases the mean probability of survival from around 40 years in a low-density RO (one standard deviation below the mean density score) to 70 years (see Fig. 2). Generally speaking, that means that membership in a highly autocratic RO makes survival for members with similar numbers of past democratic failures more than six times more likely compared to membership in a RO with mean density scores.

This finding is interesting particularly considering that the literature on the international dimension of authoritarian resilience has so far mostly argued that regional powers have a stabilizing effect on neighboring autocracies and often work through ROs (e.g. Bader, 2015; Tansey, 2016a; Tolstrup, 2015). However, it seems that the presence of a regional power does not systematically influence survival times of autocratic incumbents, and neither protects vis-à-vis democratic nor autocratic challengers. In fact, recent research even suggests that attempts at influencing neighboring regimes can sometimes even lead to unintended effects, whereby autocratic powers inadvertently turn liberal reform coalitions towards Western partners instead of tying them to their camp (Börzel, 2015). In consequences, this finding suggests that the institutional commitment between a critical mass of like-minded regional allies seems to be the key factor affecting survival.

This becomes clear when looking at the role that ROs have played in recent cases of political turmoil within authoritarian regimes. Saudi Arabia was only able to send troops to support neighboring Bahrain as part of the GCC Peninsular Shield Force during the Arab Spring crisis in 2011, which provided the legitimacy of an institutionalized military framework. Bahrain’s King Hamad officially asked for GCC forces to assist in managing protestors, with Kuwait and the UAE also contributing to the joint mission (Bahrain News Agency, 2011). In contrast, Saudi Arabia acted much more hesitant during the 2018 diplomatic crisis with Qatar where two of the GCC member states, Kuwait and Oman, remained neutral. It had to rely on unilateral diplomatic sanctions, and was unable to employ the GCC to further its own interests. Similarly, member states of SADC were restrained by the institutional norm of solidarity during the election crisis in Zimbabwe in 2008, with none of the critical powers being able to push for regional sanctions or unilateral interference outside of the SADC framework (Nathan, 2012).

Finally, it is important to note that membership in an autocrat’s club only helps to prevent democratic regime change but not autocratic replacements. Thus, we should rather talk about a system-boosting effect of RO membership instead of regime-boosting regionalism. Incumbents hoping for help to avert autocratic challenges from inside the ruling coalition such as military coups are less likely to benefit from their RO membership. Only when the status-quo of autocratic rule within a regime is at stake and by extension the risk of democratization for the larger region increases, does RO membership provide protection for autocratic incumbents.

A potential explanation could be that autocrats might only be willing to offer pooled resources and stick to their commitment of sovereignty protection when they perceive the threat to be potentially affecting their own regimes as well. Democratic regime change is a threat that is shared by all autocratic regimes independent of autocratic regime type (Geddes et al. 2014), and tends to diffuse quickly within regions (Brinks & Coppedge, 2006). Autocratic challenges, however, differ profoundly from one type of autocratic regime to the next. While monarchies, are, for instance, volatile to palace revolts from within a royal family, dominant-party and personalist regimes are more often threatened by rival political leaders that instigate revolutions (Geddes, 1999). Military regimes, in contrast, mostly end due to internal elite splits as has been evidenced by the transition literature focusing on Latin America (O’Donnell et al., 1986). Thus, perceptions of similarity might filter to what extent regimes consider domestic challenges to potentially affect regime stability at home. Unless all RO members share similar domestic institutional structures, autocrats only share a similar threat to experience democratic regime change. This explanation also speaks to literature on the role of threat perception to explain the spread of revolutionary movements (Weyland, 2012) as well as literature on foreign policy choice during times of uncertainty (Odinius & Kuntz, 2015).

The finding became particularly pronounced during the 2017 military coup in Zimbabwe. While SADC supported Mugabe’s dominant-party regime during the large-scale election crisis in 2008, the RO remained uninvolved during the disempowerment of Mugabe by his own ZANU-PF cronies in November 2017. The election crisis in 2008 revolved around state-society relations, and would very likely have resulted in a democratic turnover of government to the opposition party. The 2017 military coup, in contrast, involved intra-party elites aiming to replace Mugabe with another loyal party member. In fact, Emmerson Mnangagwa, Zimbabwe’s Vice President and long-time ally of Mugabe, was sworn in as new President on November 24, 2017, ensuring the continuation of the autocratic rule of the ZANU-PF regime without any regional interference.

5 Conclusion

The potential dark side of RO membership has received increased attention in recent research. However, the lack of theorization and cross-case comparative evidence has impaired the ability to come to more generalizable statements with regard to the conditions under which autocratic incumbent regimes might actively benefit from RO membership. Throughout the article, I have therefore provided theoretical considerations and empirical evidence to illuminate the relationship between RO membership and autocratic regime survival.

I have argued that RO membership can increase incumbent survival in two ways. First, ROs regulate the relationship between regional neighbors by institutionalizing non-interventionist norms that shield regimes from unwanted external interference into politically sensitive areas of domestic politics, thereby decreasing the risk of employing authoritarian survival strategies. Second, RO membership provides access to additional resources for autocratic incumbents to boost survival strategies vis-à-vis domestic challengers during moments of political upheaval. However, I hypothesized that only “Clubs of Autocrats”, that is, ROs composed of more autocratic member states, as well as ROs with lower levels of authority should be likely to provide the expected benefits. This is, because democracies and liberalizing member states employ ROs to protect democratic governance, while autocracies exploit them to stabilize the non-democratic status-quo. The findings from survival analysis show that autocracies indeed tend to sort into “Clubs of Autocrats”, and that their membership does decrease the risk for democratic regime change. However, membership does not protect regimes from autocratic challengers from within the ruling coalition.

The article has three important theoretical implications. First, the findings lend further support to the growing research agenda that argues that ROs can have independent effects on domestic political processes (Libman & Obydenkova, 2013; Pevehouse, 2002a). Mostly associated with liberal theory, this article extends the argument to demonstrate that ROs also matter for the domestic politics of non-democratic regimes. In this respect, previous research has focused primarily on the role of autocratic powers in deliberately shaping politics in neighboring states (Tansey, 2016a). Our findings show that institutionalized cooperation also plays a significant role to explain how autocratic regimes manage to deal with democratic challengers to survive in power.

Second, and relatedly, the findings speak to research highlighting the potential dark sides of international cooperation (Ferry et al., 2020; Hafner-Burton & Schneider, 2019; Debre 2020, 2021). By explicitly theorizing and testing reverse effects that ROs can have on domestic politics outside of Europe and the democratization paradigm, the paper elucidates the conditions under which international institutions can produce democracy or strengthen authoritarian rule. Against the backdrop of increasing democratic backsliding and legitimacy challenges towards multilateral cooperation (Hooghe & Marks, 2009; Pepinsky & Walter, 2019), it will be particularly important to study consequences of changing membership compositions of ROs and their international and domestic effects in future research. While previous waves of democratization have led to the adoption of good governance standards (Börzel & van Hüllen, 2015), the current wave of autocratization (Lührmann & Lindberg, 2019) might have significant consequences for the future protection of liberal norms and add to the deepening of the crisis of the liberal international order (Copelovitch & Pevehouse, 2019; Hooghe et al., 2019a; Kentikelenis & Voeten, 2020; Morse & Keohane, 2014).

Finally, the findings in this article also have consequences for the study of institutional design of IGOs. If regimes tend to sort into their respective democratic and autocratic camps, we might suspect that differences in domestic regime type should also lead to different institutional design choices. Previous research does show that democratic membership systematically shapes institutional design dimensions from transparency, to accountability, or openness (Grigorescu, 2010, 2015; Moravcsik, 2000; Tallberg et al., 2016). In turn, Carlson and Koremenos (2021) find that absolute autocratic monarchies tend to cooperate less formally compared to democratic and mixed dyads. Data in Hooghe et al. (2019b) also indicates that community-based organizations such as autocratic ASEAN are less likely to contain pooled decision-making procedures, while their secretariats are just as likely to be endowed with delegated authority as ROs in the democratic OECD World. Future research should therefore test to what extent autocratic regimes do indeed negotiate different institutional arrangements.

Notes

I only exclude Oman from the dataset because it represents an extreme outlier case with 268 years of uninterrupted autocratic rule since the establishment of an independent Sultanate in 1742.

Following Pevehouse (2005), theoretically, it should be enough to be a member in one organization for the effect to work. If a country is a member in several autocratic ROs of which one or more turns more democratic, the country can still profit from the most autocratic RO to stabilize its rule. Thus, theoretically it should be enough to look at the most autocratic RO of which country i is a member of at a given point in time to see if it has an effect on survival.

While a more fine-grained measures of regional authority would be preferable, currently available data do not allow for such measures to be used in this article. The MIA dataset by Hooghe et al (2017) for instance only captures a subsection of the sample employed in this paper, while the dataset employed by Zürn (2018) only covers the 30 most important IGOs.

While the study period begins in 1946, some autocracies that have been independent sovereign states before that date enter the risk set with the first independent autocratic year and are thus not left-censored. Thus, survival times can exceed the time of the study period.

I also tested for potential interaction effects between the two main independent variables autocratic density and authority but do not find significant effects. The weak results for the authority variable could be due to the dichotomous measurement, whereby a more differentiated measurement of different facets of authority might produce different results. Current datasets on international authority (Börzel and Zürn 2021; Hooghe et al. 2017) do, however, not cover the range of ROs included in this article.

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). Why states act through formal international organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002798042001001

Acharya, A. (2003). Democratisation and the prospects for participatory regionalism in Southeast Asia. Third World Quarterly, 24(2), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659032000074646

Acharya, A. (2016). Regionalism beyond EU-centrism. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. (pp. 109–132). Oxford University Press.

Acharya, A., & Johnston, A. I. (2007). Conclusion: Institutional features, cooperation effects, and the agenda for further research on comparative regionalism. In A. Acharya & A. I. Johnston (Eds.), Crafting cooperation: Regional institutions in comparative perspective. (pp. 244–278). Cambridge University Press.

Ahlquist, J. S., & Wibbels, E. (2012). Riding the wave: World trade and factor-based models of democratization. American Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00572.x

Allison, R. (2008). Virtual regionalism, regional structures and regime security in Central Asia. Central Asian Survey, 27(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930802355121

Alter, K. J. (2014). The new terrain of international law: Courts, politics, rights. Princeton University Press.

Alter, K. J., & Hooghe, L. (2016). Regional dispute settlement. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. (pp. 539–558). Oxford University Press.

Ambrosio, T. (2008). Catching the ‘Shanghai Spirit’: How the Shanghai cooperation organization promotes authoritarian norms in Central Asia. Europe-Asia Studies, 60(8), 1321–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130802292143

Ambrosio, T. (2010). Constructing a framework of authoritarian diffusion: Concepts, dynamics, and future research. International Studies Perspectives, 11(4), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00411.x

Bach, D. (2005). The global politics of regionalsim: Africa. In M. Farrell, B. Hettne, & L. van Langenhove (Eds.), Global politics of regionalism. Theory and practice. (pp. 171–186). Pluto Press.

Bader, J. (2015). Propping up dictators? Economic cooperation from China and its impact on authoritarian persistence in party and non-party regimes. European Journal of Political Research, 54(4), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12082

Bahrain News Agency. (2011). UAE dispatches troops to Bahrain. http://www.bna.bh/portal/en/news/449904?date=2011-04-9. Accessed 15 December 2017.

Bank, A., & Edel, M. (2015). Authoritarian regime learning : Comparative insights from the Arab Uprisings (No. 274). Hamburg: German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA).

Barnett, A., & Solingen, E. (2007). Designed to fail or failure of design? The origins and legacy of the Arab League. In A. Acharya & A. I. Johnston (Eds.), Crafting cooperation: Regional institutions in comparative perspective. (pp. 180–220). Cambridge University Press.

Beblawi, H., & Luciani, G. (1987). The Rentier State. Croom Helm.

Bermeo, N. (2016). On democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012

Börzel, T. A. (2015). The noble west and the dirty rest? Western democracy promoters and illiberal regional powers. Democratization, 22(3), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.1000312

Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2003). Conceptualizaing the domestic impact of Europe. In K. Featherstone & C. M. Radaelli (Eds.), The politics of Europeanization. (pp. 57–82). Oxford University Press.

Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2016a). Three cheers for comparative regionalism. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics. (pp. 621–648). Oxford University Press.

Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2016b). Introduction. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. (pp. 3–15). Oxford University Press.

Börzel, T. A., & van Hüllen, V. (2015). Governance transfer by regional organizations: Patching together a global script. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.1000312

Börzel, T. A., & Zürn, M. (2021). Contestations of the liberal international order: From liberal multilateralism to postnational liberalism. International Organization, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000570

Brinks, D., & Coppedge, M. (2006). Diffusion is no illusion: Neighbor emulation in the third wave of democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 39(4), 463–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005276666

Brownlee, J. (2007). Authoritarianism in an age of democratization. Cambridge University Press.

Bruszt, L., & Palestini, S. (2016). Regional development governance. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. Oxford University Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Randolph, S. M., & Morrow, J. D. (2003). The logic of political survival. MIT Press.

Carlson, M., & Koremenos, B. (2021). Cooperation failure or secret collusion? Absolute monarchs and informal cooperation. The Review of International Organizations, 16(1), 95–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09380-3

Cheibub, J. A., & Vreeland, J. R. (2011). Economic development and democratization. In N. J. Brown (Ed.), The dynamics of democratization. Dictatorship, development, and diffusion. (pp. 145–182). The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Collins, K. (2009). Economic and security regionalism among patrimonial authoritarian regimes: The case of Central Asia. Europe-Asia Studies, 61(2), 249–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130802630854

Cooley, A., & Heathershaw, J. (2017). Dictators without borders: Power and money in Central Asia. Yale University Press.

Copelovitch, M., & Pevehouse, J. C. W. (2019). International organizations in a new era of populist nationalism. Review of International Organizations, 14(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09353-1

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., et al. (2020). V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20

Cox, R. D. (1972). Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 34(2), 187–220

Debre, M. J. (2020). Legitimation, regime survival, and shifting alliances in the Arab League: Explaining sanction politics during the Arab Spring. International Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120937749

Debre M.J. (2021) The dark side of regionalism: how regional organizations help authoritarian regimes to boost survival. Democratization, 28(2), 394–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1823970

Debre, M. J., & Morgenbesser, L. (2017). Out of the shadows: Autocratic regimes, election observation and legitimation. Contemporary Politics, 23(3), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304318

Dukalskis, A., & Gerschewski, J. (2017). What autocracies say (and what citizens hear): Proposing four mechanisms of autocratic legitimation. Contemporary Politics, 23(3), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304320

Fearon, J. D. (1997). Signaling foreign policy interests. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002797041001004

Ferry, L. L., Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Schneider, C. J. (2020). Catch me if you care: International development organizations and national corruption. Review of International Organizations, 15(4), 767–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09371-z

Gandhi, J. (2008). Political institutions under dictatorship. Cambridge University Press.

Gasiorowski, M. J. (1995). Economic Crisis and Political Regime Change: An Event History Analysis. The American Political Science Review, 89(4), 882–897. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082515

Geddes, B. (1999). Authoritarian breakdown: Empirical test of a game theoretic argument. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association, Atlanta, September 1999.

Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(02), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714000851

Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2018). How dictatorships work: Power, personalization, and collapse. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316336182

Gerschewski, J. (2013). The three pillars of stability: Legitimation, repression, and co-optation in autocratic regimes. Democratization, 20(1), 13–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738860

Gilpin, R. (1981). War and change in world politics. Cambridge University Press.

Gilpin, R. (1987). The political economic of international relations. Princton University Press.

Gleditsch, K. S., & Ward, M. D. (2006). Diffusion and the international context of democratization. International Organization, 60(04), 911–933. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818306060309

Gray, J. (2015). The patronage function of international organizations. Unpublished Book Manuscript. https://sites.sas.upenn.edu/jcgray/files/patronage-2014_0.pdf. Accessed 18 December 2017

Greenhill, B. (2015). Transmitting Rights: International Organizations and the Diffusion of Human Rights Practices. Oxford University Press. Accessed 3 April 2021.

Grigorescu, A. (2010). The spread of bureaucratic oversight mechanisms across intergovernmental organizations. International Studies Quarterly, 54(3), 871–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00613.x

Grigorescu, A. (2015). Democratic intergovernmental organizations? Normative pressure and decision-making rules. Cambridge University Press.

Haber, S., & Menaldo, V. (2011). Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A preappraisal of the resource curse. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000584

Hadenius, A., & Teorell, J. (2007). Pathways from authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy, 18(1), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2007.0009

Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2009). Forced to Be Good: Why Trade Agreements Boost Human Rights. Cornell University Press.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Schneider, C. J. (2019). The dark side of cooperation: International organizations and member corruption. International Studies Quarterly, 63(4), 1108–1121. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz064

Hall, P., & Taylor, R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

Hancock, K. J., & Libman, A. (2016). Eurasia. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. (pp. 202–224). Oxford University Press.

Hartmann, C. (2016). Sub-Saharan Africa. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. (pp. 271–294). Oxford University Press.

Hellquist, E. (2015). Interpreting sanctions in Africa and Southeast Asia. International Relations, 29(3), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117815600934

Herbst, J. (2007). Crafting regional cooperation in Africa. In A. Acharya & A. I. Johnston (Eds.), Crafting cooperation: Regional institutions in comparative perspective. (pp. 129–180). Cambridge University Press.

Hooghe, L., Lenz, T., & Marks, G. (2019a). Contested world order: The delegitimation of international governance. Review of International Organizations, 14(4), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9334-3

Hooghe, L., Lenz, T., & Marks, G. (2019b). A theory of international organization. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198766988.001.0001

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Lenz, T., Bezuijen, J., Ceka, B., & Derderyan, S. (2017). Measuring international authority (Vol. III). Oxford University Press.

Hulse, M., & van der Vleuten, A. (2015). Agent run Amuck: The SADC Tribunal and Governance Transfer Rollback. In T. A. Börzel & V. van Hüllen (Eds.), Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations Patching Together a Global Script. (pp. 89–106). Palgrave Macmillan.

Huntington, S. P. (2006). Political order in changing societies. Yale University Press.

Ikenberry, G. J. (2001). After victory: institutions, strategic restraint, and the rebuilding of order after major wars. Princeton University Press.

Jetschke, A. (2015). Why Create a Regional Human Rights Regime? The ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission for Human Rights. In T. A. Börzel & V. van Hüllen (Eds.), Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations. Patching Together a Global Script. (pp. 107–124). Palgrave Macmillan.

Jetschke, A., & Katada, S. N. (2016). Asia. In T. Börzel, Tanja A.; Risse (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism (pp. 225–248). Oxford University Press.

Kararach, G. (2014). Development Policy in Africa: Mastering the Future? Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelley, J. G. (2012). Monitoring Democracy: When International Election Observation Works, and Why it Often Fails. Princeton University Press.

Kentikelenis, A., & Voeten, E. (2020). Legitimacy challenges to the liberal world order: Evidence from United Nations speeches, 1970–2018. Review of International Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09404-y

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After hegemony: Cooperation and discord in the world political economy. Princeton University Press.

Kono, D. Y., & Montinola, G. R. (2013). The uses and abuses of foreign aid: Development aid and military spending. Political Research Quarterly, 66(3), 615–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912456097

Korany, B. (1986). Political petrolism and contemporary arab politics 1967–1983. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 21(2), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852186X00053

Laruelle, M. (2008). Russian eurasianism: An ideology of empire. Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Lenz, T., & Marks, G. (2016). Regional institutional design: Pooling and delegation. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. (pp. 513–537). Oxford University Press.

Libman, A., & Obydenkova, A. (2013). Informal governance and participation in non-democratic international organizations. Review of International Organizations, 8(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9160-y