Abstract

States and international organizations often attempt to influence the behavior of a target government by employing conditionality—i.e., they condition the provision of some set of benefits on changes in the target’s policies. Conditionality may give rise to a commitment problem: once the proffered benefits are granted, the target’s incentive for continued compliance declines. In this paper, I document a mechanism by which conditionality may induce compliance even after these benefits are distributed. If conditionality alters the composition of domestic interest groups in the target state, it may induce permanent changes in the target government’s behavior. I construct a dynamic model of lobbying that demonstrates that conditionality can reduce long-term levels of state capture. And I test the model’s predictions using data from the accession of Eastern European countries to the EU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, there may be reason to suspect non-compliance even in the short term. Studies of IMF conditionality find high levels of non-compliance based on a variety of measures (for a comprehensive overview see Vreeland 2006). In keeping with the findings of this paper, there is evidence that domestic special interests (Ivanova et al. 2001) affect levels of short-term compliance; as do domestic political institutions such as democracy (Dreher 2006; Joyce 2004).

Breaking the Bank, The Economist. September 25, 2008. http://www.economist.com/world/mideast-africa/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12305409.

State capture here is defined as the ability of an organized interest group to determine state policy. For more on state capture in Eastern Europe see Hellman et al. (2000). Stigler (1971) and Peltzman (1976) pioneer theories of regulatory capture. This phenomenon may be thought of as analogous to state capture, but on a narrower scale.

Throughout the paper, I refer to ‘lobbying’ as encompassing both licit and illicit efforts to influence government behavior. State capture may result from both forms of lobbying; though corruption only properly refers to illicit efforts. The theoretical model developed below, which is built on the Grossman and Helpman (1994) framework, does not distinguish between licit and illicit lobbying. In this framework, lobbying is modeled in a very reduced form and general manner, and simply reflects the exchange of benefits for influence over the legislative process. The simplified manner in which lobbying is modeled is sufficient to develop theoretical predictions, without generating undue complexity by differentiating between different forms of influencing the legislature.

For instance, the EU Commission, in a strategy paper on enlargement, listed the “fight against corruption” as one of the elements—along with civil rights and human rights—as issues of central concern to the political Copenhagen Criteria (as cited in Vachudova 2005, 122).

The Russian case, while not directly applicable to EU accession, is particularly instructive. Guriev and Rachinsky (2005) document how oligarchic elites were able to band together to form their own lobbying organization (the RSPP) to influence government actions. Klebnikov (2000) documents the extensive influence wielded by a small band of oligarchic elites in Yeltsin’s 1996 election campaign.

Opinions were issued regarding the progress of each of the new applicants and were subsequently integrated into the Agenda 2000 report. This report would establish the framework for negotiations between Eastern European countries and the EU through 2007.

Cleaning up the Act, The Economist. November 20, 2008. http://www.economist.com/world/europe/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12636216.

EU enforcement in other areas has also been found to be weak. The European Growth and Stability Pact established fiscal policy targets for Economic Monetary Union members, enforceable by fines and other punitive measures. But despite violations of these targets, the EU has been reticent to resort to punitive measures and has instead weakened the requirements imposed on member-states (Annett 2005; Beetsma and Debrun 2005; Buti et al. 2003). On related lines, Franzese and Hays (2006) find substantial free riding in active labor market policies, despite efforts to coordinate these policies through the European Economic Strategy.

Brussels Busts Bulgaria, The Economist July 17, 2008. http://www.economist.com/world/europe/displaystory.cfm?story_id=11751745.

The World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (WGI) describe governments’ performance across a variety of dimensions. The WGI measures are constructed from an unobserved components analysis used to assess the common variance in a large number of other sources (Kaufmann et al. 2007). Assigned values range from −2.5 to 2.5. For the control of corruption indicators, higher values indicate lower levels of corruption.

In the sample of eventual EU member-states, Hellman classified Estonia, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania as trapped in partial reform equilibria. Though, he notes that concentrated influence by ‘winners’ in the transition from communism was a problem for Eastern European states more broadly.

See Rajan and Zingales (2003) for a more developed exposition of this claim.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this point.

This method of modeling the EU decision process allows me to capture the essence of the nature of the Copenhagen Criteria and the aquis without unduly burdening the model with complexity. Mayer and Mourmouras (2005) construct a more developed model of IMF conditionality using a common agency framework in which the IMF acts to maximize the utility of foreign governments. However, in this instance, since the criteria for EU admission were constructed prior to extensive negotiation and were allegedly identical across applicants, the simple form of conditionality used here seems more appropriate. It also allows me to avoid making burdensome assumptions about the EU’s utility function.

Throughout, I treat N as denoting the number of incumbent firms and n as denoting the number of firms in the market. Thus, n = N if entry does not take place. n = N + 1 if entry does take place.

Throughout I assume corner solutions are not reached. The possibility of corner solutions does not change the comparative statics of the model. See Appendix for proof.

See Appendix for derivation.

The construction of the model borrows from Gailmard (2009).

I drop the time subscript below for notational convenience.

Note that W(θ) is linear and decreasing in θ. Therefore, the government’s preferred level of θ absent any bribes will always be a corner solution, i.e., θ = 0.

See Appendix for derivation.

Note that the Inada conditions imply that V′ − 1( ∞ ) = 0 and V(V′ − 1( ∞ )) = 0.

See Appendix for derivation.

It is important to note that the government does not have an incentive to alleviate this coordination failure. The government’s incentive compatibility constraint is satisfied at equality, and it therefore does not prefer any lobbying outcome to another.

For a V(.) of the form V(x) = Bx α where \(B>0~\text{and}~\alpha \in [0,1]\), this property will hold if V(.) is sufficiently concave. If V(.) is such that \(4[\frac{1}{2}V(V'^{-1}(\frac{1}{4})) - V(V'^{-1}(\frac{1}{2}))]>\frac{1}{2}V'^{-1}(\frac{1}{4}) - V'^{-1}(\frac{1}{2})\), then multiple equilibria arise. A coordination game emerges. Either no firms lobby or both firms will do so. I assume throughout that this concavity property holds. See Appendix for further details.

Since V(.) is strictly concave, \(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)>V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\). This implies that the equilibrium level of θ is higher in the two-incumbent case than in the one-incumbent case when both firms lobby. Moreover, \(\frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)>\frac{72bR}{5(a-c)^2}V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)\) implying that θ is strictly higher in the two-incumbent case than in the one incumbent case so long as at least one firm is lobbying.

Incumbent and de novo firm lobbying behavior would ‘cancel each other out’ in the Grossman Helpman framework.

See “Notes on Panel Dataset’ for the ECA region at http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/Portal/elibrary.aspx?libid=14. Registration is required.

The Enterprise Surveys do not specify whether this lobbying is licit or illicit. However, it seems probable that firms that engage in extensive illicit influence peddling will pass off such efforts as ‘lobbying’ the government. I implicitly assume that the probability that a given firm states that it lobbies is increasing in the level of effort devoted to influencing the government. To the extent that this is not true, or to the extent that firms engaged in illicit attempts to influence the government deny any lobbying activity, my estimates will tend to be biased towards zero. Absent credible information on the level of bribes paid to influence the government by a given firm, these data are the best test of the theory that could be hoped for. This implicit relationship is particularly likely to hold within a given country and within a given sector, i.e., once country and sector fixed-effects are controlled for. This assumption is further supported by results—available from the author on request—that demonstrate that lobbying is positively associated with a firm’s perception of the effectiveness of bribes paid to the legislature.

The index takes eight different values, with all scores between 1 and 4.

The ICRG Corruption Risk index contains panels that extend to earlier periods. However, coverage in Eastern Europe during this period is poor. Only six panels contain observations before EU applicant status is granted.

See, for instance, http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi/2009/methodology.

Applicant status is coded based on the date that official applications for membership are received by the EU.

Plotting the competition policy index clearly reveals a non-linear time trend. Moreover, Beck et al. (1998) advise controlling for time trends when working with discrete (in their case binary) TSCS data; Carter and Signorino (2007) suggest using a cubic function of time for this purpose. In this instance, t = 1 in 1989, t = 2, in 1990, etc. I add controls for t, t 2 and t 3 to the regression model. This specification allows for a flexible time trend while avoiding complete and quasi-separation that may result from dummies (Carter and Signorino 2007). Given the potential incidental parameters problem that arises from estimating fixed-effects in non-linear (and particularly in dynamic non-linear) models (Wooldridge 2002), the use of a time trend is to be preferred.

Alternative methods to control for such selection effects might employ Heckman selection models or propensity score matching. Given the relative sparseness of panels in this dataset, however, pruning panels based on propensity score matching seems ill-advised. Heckman models are only cleanly identified in the event that variables can be found that satisfy an exclusion restriction—i.e., that affect the probability of selection into the EU but do not effect competition policy. Very few measures can credibly meet this constraint—and failure to meet this constraint leads to estimates that are both biased and inefficient. I thus prefer to rely on the models above that may be considered as evidence of an association consistent with theoretical predictions; though not as definitive evidence as a causal effect of EU membership policies.

Models that include a lagged-dependent variable will also encounter bias in the presence of residual autocorrelation (Keele and Kelly 2006). To address this possible issue, I rerun the OLS estimates (unreported) from Table 1 correcting for possible first-order autocorrelation, as recommended by Keele and Kelly (2006). Coefficient estimates of interest are substantively unchanged. (The modified Durbin–Watson statistic is approximately 1.45 in models both with and without fixed-effects.)

For this panel of countries, both measures will be highly correlated with levels of trade and FDI flows with the EU.

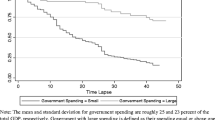

Predicted probabilities are generated setting all economic variables to their mean levels in the dataset, setting the year equal to 1998 and the country fixed-effects so that the Czech Republic is the country under observation.

These predicted values are generated for the year following the grant of applicant status. The model would predict greater long term associations, as current changes in competition policy affect competition policy in the next period (thus, long term equilibrium effects are equal to the coefficient on the variable of interest multiplied by the reciprocal of one minus the coefficient on the lagged dependent variable when estimated using OLS).

These data are, in some senses, less than ideal to test the theory advanced. Ideally, one would like panel data from 1989 through the present on levels of both licit and illicit lobbying activities. However, such panel data are not (to my knowledge) available at the firm level. And it seems likely that any information beyond the simple {yes, no} lobbying question posed by the Enterprise Surveys would elicit significant non- and false responses. I therefore make use of available data and run tests that may offer supportive, if not conclusive, evidence for the theoretical propositions advanced.

This variable is coded based upon the year in which a firm begins operations in a given country, whether or not it is privatized, and the year in which a government gains applicant status to the EU. Since I only have data on the year in which the firm began business, I use the year in which the country was formally afforded applicant status to calculate whether or not it began operations during the application period. If awarded applicant status after the month of June, I round the year up.

Since I am working from a sample of firms—rather than with the full population—it remains open to question whether these measures are sufficiently accurate to capture the variables of interest. Since a simple random sample of registered firms is used, survey results are likely to be representative. However, they are likely to be best suited to making comparisons within countries (since factors affecting sampling—such as firm registration rules—may vary across countries). Thus, I prefer specifications that control for country fixed-effects.

As it seems probable that both entry and lobbying behavior may vary across countries and across sectors due variables omitted from the regression, controlling for both sets of fixed-effects should be preferred. Moreover, as noted above, the lobby variable is most likely to proxy for variation in illicit activity when country and sector fixed-effects are controlled for.

Estimates are generated setting Log Num. Preexisting to its mean value, legal status, domestic private ownership, and size to median values, for a publicly traded domestic manufacturing firm in Poland.

Derivation available on request.

References

Abiad, A., & Mody, A. (2005). Financial reform: What shakes it? What shapes it? The American Economic Review, 95, 66–88.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters, 80, 123–129.

Albi, A. (2005). EU enlargement and the constitutions of central and eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alesina, A., & Drazen, A. (1991). Why are stabilizations delayed? The American Economic Review, 81(5), 1170–1188.

Annett, A. (2005). Enforcement and the stability and growth pact: How fiscal policy did and didn’t change under Europe’s fiscal framework.

Avery, G., & Cameron, F. (1998). The enlargement of the European union. London: Sheffield Academic.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. (2009). Modeling dynamics in time-series-cross-section political economy data. California Institute of Technology Social Science Working Paper.

Beck, N., Katz, J. N., & Tucker, R. (1998). Taking time seriously: Time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. American Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 1260–1288.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: The database of political institutions. World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Beetsma, R. M. W. J., & Debrun, X. (2005). Implementing the stability and growth pact: Enforcement and procedural flexibility. IMF Working Paper.

Berry, W. D., DeMeritt, J. H. R., & Esarey, J. (2010). Testing for interaction effects in binary logit and probit models: Is an interaction term necessary. The American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 248–266.

Blauberger, M. (2009). Compliance with rules of negative integration: European state aid control in the new member state. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(7), 1030–1046.

Bombardini, M. (2008). Firm heterogeneity and lobby participation. Journal of International Economics, 75, 329–348.

Bombardini, M., & Trebbi, F. (2009). Competition and political organization: Together or alone in lobbying for trade policy.

Braguinsky, S. (2007). The rise and fall of the post-communist oligarchs: Legitimate and illegitimate children of praetorian communism.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2005). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 13, 1–20.

Buti, M., Eijffinger, C. W., & Franco, D. (2003). Revisiting the stability and growth pact: Grand design or internal adjustment. CEPR Discussion Paper Series.

Carter, D. B., & Signorino, C. S. (2007). Back to the future: Modeling time dependence in binary data. The Society for Political Methodology Working Paper.

Dimitrova, A., & Toshkov, D. (2009). Post-accession compliance between administrative co-ordination and political bargaining. European Integration Online Papers, 13.

Dreher, A. (2006). IMF and economic growth: The effects of programs, loans, and compliance with conditionality. World Development, 34, 765–788.

Falkner, G., & Treib, O. (2008). Three worlds of compliance or four? The EU-15 compared to new member states. Journal of Common Market Studies, 46(2), 293–313.

Fernandez, R., & Rodrik, D. (1991). Resistance to reform: Status quo bias in the presence of individual-specific uncertainty. The American Economic Review, 81(5), 1146–1155.

Franzese, R. J., Jr., & Hays, J. C. (2006). Strategic interaction among EU governments in active labor market policy-making. European Union Politics, 7(2), 167–189.

Frydman, R., & Rapaczynski, A. (1994). Privatization in eastern Europe: Is the state withering away? Central European University Press.

Gailmard, S. (2009). Multiple principals and oversight of bureaucratic policy-making. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 21, 161–186.

Gray, J. (2009). International organization as a seal of approval: The European union accession and investor risk. The American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 931–949.

Greene, W. (2010). Testing hypothesis about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Economic Letters, 107, 291–296.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. The American Economic Review, 84(4), 833–850.

Guriev, S., & Rachinsky, A. (2005). The role of oligarch in Russian capitalism. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 131–150.

Hellman, J. S. (1998). Winners take all: The politics of partial reform in postcommunist transitions. World Politics, 50(2), 203–234.

Hellman, J. S., Jones, G., & Kaufmann, D. (2000). “Seize the state, seize the day” state capture, corruption and influence in transition. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

Hellman, J. S., & Schankerman, M. (2000). Intervention, corruption and capture: The nexus between enterprises and the state. Economics of Transition, 8(3), 545–576.

Hsiao, C. (2003). Analysis of panel data (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ivanova, A., Mayer, W., Mourmouras, A., & Anayiotos, G. (2001). What determines the success or failure of fund-supported programs. IMF Working Paper.

Jackson, J. E., Klich, J., & Poznańska, K. (2005). The political economy of Poland’s transition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, J. P. (2004). The adoption, implementation, and impact of IMF programs: A review of the issues and evidence. Comparative Economic Studies, 46, 451–467.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2007). Governance matters vi: Aggregate and individual governance indicators 1996–2006. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4280.

Keele, L., & Kelly, N. J. (2006). Dynamic models for dynamic theories: The ins and outs of lagged dependent variables. Political Analysis, 14, 186–205.

Klebnikov, P. (2000). Godfather of the Kremlin: Boris Berezovsky and the Looting of Russia. New York: Harcourt.

Levitz, P., & Pop-Eleches, G. (2009). Why no backsliding? The European Union’s impact on democracy and governance before and after accession. Comparative Political Studies, 20(10), 1–29.

Mayer, W., & Mourmouras, A. (2005). The political economy of IMF conditionality: A common agency model. Review of Development Economics, 9(4), 449–466.

Meyer-Sahling, J.-H. (2008). The changing colours of the post-communist state: The politicization of the senior civil service in Hungary. European Journal of Political Research, 47, 1–33.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1982). Predation, reputation, and entry deterrence. Journal of Economic Theory, 27, 280–312.

Mitra, D. (1999). Endogenous lobby formation and endogenous protection: A long run model of trade policy determination. The American Economic Review, 89(5), 1116–1134.

Nagler, J. (1991). The effect of registration laws and education on U.S. voter turnout. The American Political Science Review, 85, 1393–1405.

Olson, M., Jr. (1971). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pecorino, P. (2001). Market structure, tariff lobbying, and the free rider problem. Public Choice, 106, 203–220.

Peltzman, S. (1976). Toward a more general theory of regulation. The Journal of Law and Economics, 19(2), 211–240.

Pridham, G. (2008). The EU’s political conditionality and post-accession tendencies: Comparisons from Slovakia and Latvia. Journal of Common Market Studies, 46(2), 365–287.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (2003). Saving capitalism from the capitalists. New York: Crown Business.

Stigler, G. J. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

Tomz, M., Wittenberg, J., & King, G. (2001). Clarify: Software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. version 2.0. http://gking.harvard.edu. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Toshkov, D. (2008). Embracing European law: Compliance with EU directives in central and eastern Europe. European Union Politics, 9(3), 379–402.

Vachudova, M. A. (2005). Europe undivided: Democracy, leverage, & integration after communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Oudenaren, J. (2000). Uniting Europe: European integration and the post-cold war world. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Vreeland, J. R. (2006). IMF program compliance: Aggregate index versus policy specific research strategies. Review of International Organizations, 1(4), 359–378.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I would like to thank Sami Atallah, Nick Beauchamp, Adam Bonica, Jon Eguia, Peter Rosendorff, Shanker Satyanath, Kongjoo Shin, David Stasavage, Joshua Tucker, Johannes Urpelainen, participants in NYU’s Post-Communist Politics Seminar, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are my own.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: Formal Proofs

Appendix: Formal Proofs

1.1 Proof that, in Equilibrium, Barriers Never Rise Above Profits

Lemma 1

In equilibrium, barriers to entry will always be such that \(\theta \leq \frac{(a-c)^2}{b\!(N+2)^2}\) . That is, barriers to entry will never exceed the profits from entry.

Proof

Note that, given the benefits to entry (expression 4), the probability of entry is zero \(\forall~ \theta > \frac{(a-c)^2}{b\!(N+2)^2}\). Since the only benefits to incumbent firms from raising barriers to entry θ comes through the decline in the probability of entry, there is no incentive to raise \(\theta > \frac{(a-c)^2}{b\!(N+2)^2}\). □

1.2 Derivation of Inequality 12

The following characterizes the conditions necessary for lobbying to take place in the final round in the event that there is a single incumbent monopolist in the market. If the incumbent does not engage in lobbying, the government will set θ at its preferred level θ = 0. Given the distribution of F(r), this level of θ implies that entry will take place with certainty, and that the incumbent will enjoy profits of \(\frac{(a-c)^2}{9b}\). Therefore, lobbying will take place if the following inequality holds:

plugging in for \(\theta^*_{t=2},~\beta_{f,t=2}^* \)

1.3 Derivation of W(θ)

Social welfare is given by the expected value of the consumer surplus and producer profits. From Eq. 7, the value of the consumer surplus will be \(\frac{N^2(a-c)^2}{2b\!(N+1)^2}\) absent entry and \(\frac{(N+1)^2(a-c)^2}{2b\!(N+2)^2}\) given entry (recalling that n = N absent entry and n = N + 1 given entry). From Eq. 3, the sum of producer profits will be \(\frac{N(a-c)^2}{b\!(N+1)^2}\) absent entry and \(\frac{(N+1)(a-c)^2}{b\!(N+2)^2}\) given entry. Thus, W(θ) is given by:

simplifying

1.4 Derivation of the Equilibrium Level of Contributions and Barriers to Entry with Two Incumbent Firms

Following Grossman and Helpman (1994), each firm offers a truthful contribution schedule. Each firm that contributes will therefore set a contribution schedule such that \(\frac{\partial u_g(\theta,\beta)}{\partial \theta} = \sum_f \frac{\partial u_g(\theta,\beta)}{\partial \beta} \frac{\frac{\partial u_f(\theta, \beta_{\!f})}{\partial \theta}}{\frac{\partial u_f(\theta,\beta_{\!f})}{\partial \beta_{\!f}}}\). Moreover, each lobbying firm maximizes its utility subject to the government’s incentive compatibility constraint \(u_g(\beta^{**}_{t=2}, \theta^{**}_{t=2}) \geq u_g(0,0)\) implying:

This then implies that:

1.5 Derivation of Inequality 15

For each firm to lobby with certainty in the two-incumbent case, it must be true that each firm prefers to lobby knowing that the other firm will lobby as well. The level of barriers to entry when two firms contribute which, with some abuse of notation, I here denote \(\theta^{**}_{t=2,L=2}\) must be sufficiently large relative to that when only one firm contributes \(\theta^{**}_{t=2,L=1}\) that it compensates for each firms’ cost of lobbying \(\beta^{**}_{f,t=2,L=2}+k\). Substituting these values from identity 13 yields the following:

Proof of Proposition 2

If lobbying takes place with certainty absent entry, but does not take place with certainty given entry, it must be the case that inequality 12 holds while inequality 15 does not. By substitution, it must be the case that \(4\big[\frac{1}{2}V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\big) - V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)\big]<\frac{1}{2}V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big) - V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\). If this inequality holds, each firm will lobby with positive probability Pr(lobbies) ∈ (0,1). In such a mixed strategy equilibrium, the expected utility of each firm from engaging in lobbying must equal that from not engaging in lobbying. Denote the utility to firm f of engaging in lobbying while firm \(\neg f\) is also engaged in lobbying as \(u_f\big(\theta_{t=2,L=2}^{**},\beta_{f,t=2,L=2}^{**},k\big)\). Then:

substituting from identity 13 yields

Denote the utility to firm f of engaging in lobbying while firm \(\neg f\) does not as \(u_f\big(\theta_{t=2,L=1}^{**}, \beta_{f,t=2,L=1}^{**},k\big)\). Then:

substituting from identity 13 yields

The utility to firm f from engaging in lobbying will therefore be the weighted sum of the two identities above, where the weights are given by the probability firm \(\neg f\) engages in lobbying Pr(lobbies). This will be given by the following expression:

If firm f does not engage in lobbying, barriers to entry will be set at \(\theta_{t=2,L=1}^{**}\) in the event that firm \(\neg f\) engages in lobbying and at θ = 0 in the event that firm \(\neg f\) does not engage in lobbying. In the latter case, entry will take place with certainty. Firm f does not incur any cost from the lobbying process. Therefore, her utility will be given by the weighted sum

Setting firm f’s expected utility from lobbying equal to that from not lobbying yields the following expression:

Solving for the equilibrium value of Pr(lobbies) yields:

Note that if inequality 14 holds and inequality 15 does not, then Pr(lobbies) ∈ (0, 1). □

1.6 Incumbent Utility in the First Period of the Game

If lobbying is certain not to take place in the second round of the game—i.e., if inequality 12 does not hold—then entry will take place with certainty in the second round. The incumbent monopolist’s utility in the first round therefore only depends on whether or not entry will take place in the first round. Such entry will occur with probability 1 − F(θ t = 1) and is expressed by the following:

For notational simplicity, denote this value ω.

The expression for I’s utility if lobbying takes place with positive probability in the final round is somewhat more complicated. From Proposition 3, it follows that if lobbying takes place with positive probability in the second round, it takes place with certainty if the first challenger does not enter (i.e., with probability F(θ t = 1)). This implies that the level of contributions and of barriers to entry in the second round will be as described identity 11 above with probability F(θ t = 1). In the event that entry does take place in the first round, lobbying will take place with positive probability in the second. Assume that Pr(lobbies) ∈ (0,1). It can then be shown that the incumbent monopolist’s expected utility from the second round given entry will be \(\frac{(a-c)^2}{16b} + Pr(lobbies)\big[2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)\big]\). Then I’s first round utility is given by the weighted sum of these two terms plus her contemporaneous utility:

Simplifying:

Note that (1) \(\frac{\partial u_{I,t=1}(\theta_{t=1}, \beta_I)}{\partial \theta_{t=1}}\) declines as Pr(lobbies) rises and (2) that for sufficiently low values of Pr(lobbies), \(\frac{\partial u_{I,t=1}(\theta_{t=1}, \beta_I)}{\partial \theta_{t=1}}\) is greater given that Pr(lobbies) ∈ (0, 1) than when lobbying does not take place in the first round (as in the above).

If Pr(lobbies) = 1—i.e., inequalities 14 and 15 both hold—then the expression for the incumbent monopolist’s utility is still different. The incumbent monopolist enjoys expected utility given by the expression \(\frac{(a-c)^2}{16b} + 2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\big) - \frac{1}{2}V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big) -k > \frac{(a-c)^2}{16b} + Pr(lobbies)\big[2V(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)\big]\) in the second round given entry in the first. With probability 1 − F(θ t = 1) entry takes place and both members of the duopoly lobby in the second round. Then the expression for the incumbent monopolist’s first round utility will be given by:

Given that inequality 15 holds, the expression \(2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\big) - 2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) + V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) - \frac{1}{2}V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\) is strictly greater than zero. Therefore, \(\frac{\partial u_{I,t=1}(\theta_{t=1}, \beta_I)}{\partial \theta_{t=1}}\) is strictly lower in this instance than when Pr(lobbies) ∈ (0, 1).

It therefore follows that the incumbent monopolist’s utility varies most strongly with θ t = 1 when Pr(lobbies) ∈ (0, 1) and when Pr(lobbies) < < 1.

Proof of Proposition 5

The government’s incentive compatibility constraint requires that \(W(\theta_{t=1}^*) + V(\theta_{t=1}^*) + A(\theta_{t=1}^*) \geq W(0) + V(0) + A(0)\). Denote the solution to the equilibrium level of θ t = 1 when A = 0 (i.e., when conditionality is not applied) as \(\hat{\theta}_{t=1}\). If \(\hat{\theta}_{t=1} \leq \bar{\theta}\), then \(\theta_{t=1}^* = \hat{\theta}_{t=1}\). The equilibrium level of barriers is unaffected by conditionality. If \(\hat{\theta}_{t=1}>\bar{\theta}_{t=1}\), then the equilibrium level of barriers to entry will be affected by EU conditionality and the government’s incentive compatibility constraint. To meet the government’s incentive compatibility constraint, the incumbent monopolist must set a contribution schedule that allows for a strictly lower level of barriers (θ) in exchange for the equilibrium level of bribes \(\beta_{t=1}^*\). More precisely, \(\theta_{t=1}^*=\max\big\{\hat{\theta}_{t=1}-A\big(\frac{188bR}{(20+7\delta)(a-c)^2}\big); \bar{\theta}\big\}\). To see this, note that \(W(\theta) = \frac{(128+135\delta)(a-c)^2}{288b} - \frac{\theta_{t=1}}{R}\big[\frac{(20+7\delta)(a-c)^2}{288b}\big]\) from expression 17. Therefore, the government’s incentive compatibility constraint implies that, if \(\hat{\theta}_{t=1}>\bar{\theta}_{t=1}\), \(V(\beta^*_{t=1}) \geq \frac{\theta_{t=1}}{R}\big[\frac{(20+7\delta)(a-c)^2}{288b}\big] - A\). Satisfying this constraint implies that \(\theta_{t=1}^*=\max\big\{\hat{\theta}_{t=1}-A\big(\frac{188bR}{(20+7\delta)(a-c)^2}\big); \bar{\theta}\big\}\). This expression is weakly decreasing in A. This quantity is weakly increasing in \(\bar{\theta}\). And the range of parameters for which \(\theta_{t=1}^* > \bar{\theta}\) is decreasing in \(\bar{\theta}\). □

1.7 The Concavity of V(.)

For V(x) = Bx α, computational solutions reveal that the inequality expressed in Proposition 1, i.e., \(4\big[V(\frac{1}{2} V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\big) - V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)\big] < \frac{1}{2} V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big) - V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\) will be satisfied for values of \(\alpha \lessapprox 0.556\). If this property is not satisfied, firms may lobby given entry when they would not absent entry. More precisely, when inequality 15 is satisfied while inequality 14 is not, there exist two equilibria—one wherein both firms lobby one wherein neither firm lobby.

1.8 Corner Solutions

Assume that \(\frac{72bR}{5(a-c)^2}V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) > \frac{(a-c)^2}{9b}\), and \(2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) - V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) \geq k\). Then, absent entry in the first round, the incumbent firm will lobby with probability one such that \(\theta=\frac{(a-c)^2}{9b}\) and entry in the second round is deterred with probability 1. Now compare this case to the case given entry in the first round. Note that, since \(\theta^*_{t=2} = \frac{72bR}{5(a-c)^2}V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) < \theta^{**}_{t=2} = \frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2L}\big)\big)\) with L = 1, and the necessary level of θ to deter entry declines to \(\frac{(a-c)^2}{16b}\), if a corner solution is reached in the first round then it is reached by a single firm lobbying in the second round. This will induce a public goods game where the probability each firm lobbies in a mixed strategy equilibrium is given by: \(Pr(lobbies) = \big[\frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b} - V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big) - k\big]\big{/}\big[\frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b} - \frac{1}{2}V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big)\big] \in (0,1)\).Footnote 51 Thus the comparative statics of the model continue to hold.

Assume now that \(\frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)>\frac{(a-c)^2}{16b}\) and \(\frac{72bR}{5(a-c)^2}V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) < \frac{(a-c)^2}{9b}\) and \(2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) - V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) \geq k\). Thus, a corner solution is reached with a single firm lobbying given entry, but is not reached absent entry. The equilibrium is exactly as above, such that absent entry lobbying takes place with probability 1, and given entry each incumbent lobbies with probability \(Pr(lobbies) = \big[\frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b} - V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big) - k\big]\big{/}\big[\frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b} - \frac{1}{2}V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big)\big] \in (0,1)\).

Assume now that \(\frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)<\frac{(a-c)^2}{16b}\), but \(\frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\big)>\frac{(a-c)^2}{16b}\). Assume further \(2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) - V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) \geq k\) and \(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b} - 2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)- \frac{1}{2}V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big) < k\). Absent entry, lobbying is described as above. Given entry, if both firms lobby, a corner solution will be reached. However, each incumbent firm would prefer not to lobby, given that the other incumbent firm chooses to lobby. In this instance, a mixed-strategy equilibrium is reached wherein each firm lobbies with probability \(Pr(lobbies) = \big[2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) - \frac{1}{2}V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) - k\big]\big{/}\big[4V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) - V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) + \frac{1}{2}V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big) - \frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b}\big] \in (0,1)\). Thus the comparative statics of the model hold.

If \(\frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) < \frac{(a-c)^2}{16b},\) but \(\frac{288bR}{7(a-c)^2} V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{4}\big)\big) > \frac{(a-c)^2}{16b}\) and \(2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big) -V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big) \geq k\) and \(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{144b} - 2V\big(V'^{-1}\big(\frac{1}{2}\big)\big)- \frac{1}{2}V^{-1}\big(\frac{7(a-c)^2}{288b}\big) \geq k\), incumbent firm(s) lobby with probability 1 absent or given entry.

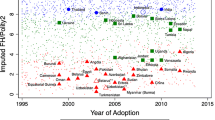

Predicted EBRD competition policy scores and EU member status. Predicted probabilities (and 95% confidence intervals) of obtaining a given EBRD competition policy score. Predictions are based on OProbit1 from Table 1. Possible EBRD competition policy index scores are reported on the x-axis, predicted probabilities are on the y-axis. Dark values reflect predictions for a country that obtained EU member status the preceding year. Light values reflect predictions for a country that did not receive such status. The graph to the left depicts predictions when the level of competition policy was at its most restrictive level (2.67) observed a year member status is granted. The graph to the right depicts predictions when the level of competition policy was at its most liberal level (3.33) observed a year before member status is granted. Predicted probabilities were generated using CLARIFY (Tomz et al. 2001) run from Stata 11

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hollyer, J.R. Conditionality, compliance, and domestic interests: State capture and EU accession policy. Rev Int Organ 5, 387–431 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9085-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9085-2