Abstract

Public opinions regarding the international economic organizations (IEOs; the IMF, World Bank, and WTO) are understudied. I contrast five lines of argument using a multi-country survey of developing countries, focusing on evaluations of the economy, skills, gender, and ideology and measures of involvement with the organizations themselves. At the individual level, respondents have negative views if they have negative views of the state of the economy. More educated respondents are more likely to have negative views of the IEOs. Women are more likely to have positive views of the IEOs than men. National levels of engagement with the IEOs also affect public evaluations of them. Evaluations of the state of the economy are more influential determinants of IEO evaluations in states that receive IMF and World Bank loans, as well as in states that are active in WTO dispute resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Compliance with IMF and World Bank programs is an important issue. For the IMF, Mussa and Savastano (1999) note that between 1973 and 1997, more than a third of all Fund arrangements ended with disbursements of less than half of the original support. World Bank (1997) reports that less than 30% of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have a good record of program compliance. As Nsouli et al. (2005:140) note, successfully implemented IMF programs exhibit better performance in inflation and fiscal policy. This is not to imply that noncompliance with IMF programs is costless. Recent work evaluating the catalytic effects of IMF programs (Edwards 2005) notes that program suspensions by the IMF lead to capital flight. Vreeland (2006) provides an extensive overview of the issues surrounding compliance with IMF programs.

The results of the survey are available at http://people-press.org/reports/pdf/165.pdf, and the codebook and data are available at http://people-press.org/dataarchive/. The Pew Global Attitudes Project bears no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations of the data presented here.

As Hayo (1999) notes, actual knowledge by Europeans about the EU is quite low.

The appendix contains the exact text of all questions used in the data analysis.

Not all the surveys were based on random samples. Thus, the analysis presented here relies on weighted data to ensure that urban respondents were not oversampled relative to rural ones.

Relying on data on flows help mitigate concerns about omitting the degree of program compliance, since the money is only given if the Fund certifies that the conditions have been met. For more on this, see Dreher (2006).

The VIFs between these national-level regressors were very low (1.81 for model with IMF, 2.73 for model with IBRD flows), which mitigates concerns about collinearity between these aggregate-level variables.

I also reestimated these models replacing the Freedom House score with the Heritage Index of Economic Freedom. The variable is significant in all models and in the same direction as the Freedom House score for education, partisanship, gender, and changes in future economic situation. The variable was significant and in the opposite direction for economic situation and household income.

References

Alesina, A., & Drazen, A. (1991). Why are stabilizations delayed? American Economic Review, 81, 1170–1188.

Banducci, S., Karp, J., & Loedel, P. (2003). The Euro, economic interests and multi-level governance: Examining support for the common currency. European Journal of Political Research, 42, 685–703.

Broz, J. L. (2008). Congressional voting on funding the international financial institutions. Review of International Organizations, 3(4), 351–374.

Cerrutti, M. (2000). Economic reform, structural adjustment, and female labor force participation in Buenos Aires, Argentina. World Development, 28(5), 879–891.

Dalla Costa, M., & Dalla Costa, G. F. (1993). Paying the price: Women and the politics of international economic strategy. London: Zed Books.

Danaher, K. (ed). (1994). 50 years is enough: The case against the world bank and the international monetary fund. Boston: South End.

Drazen, A. & Isard, P. (2004). Can public discussion enhance program ownership? IMF Working Paper WP/04/163.

Dreher, A. (2006). IMF and economic growth: The effects of programs, loans, and compliance with conditionality. World Development, 34(5), 769–788.

Duch, R. M. (1993). Tolerating economic reform: Popular support for transition to a free market in the former Soviet Union. American Political Science Review, 87(3), 590–608.

Edwards, M. S. (2005). Is non-compliance costly? Investor responses to IMF program failures. Social Science Quarterly, 84(4), 857–873.

Efron, B. (1982). The jackknife, the bootstrap and other resampling plans. Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

Eichenberg, R., & Dalton, R. (1993). Europeans and the European community: The dynamics of public support for European integration. International Organization, 47, 507–534.

Emeagwali, G. (1995). Women pay the price: Structural adjustment in Africa and the Caribbean. Trenton: Africa World.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Short and long-term effects of economic conditions on individual voting decisions. In J. Ferejohn & J. Kuklinski (Eds.), Information and democratic processes. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Franzese, R. J. (2006). Empirical strategies for various manifestations of multilevel data. Political Analysis, 13, 430–436.

Gabel, M. (1998). Economic integration and mass politics: Market liberalization and public attitudes in the European Union. American Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 936–953.

Gabel, M., & Whitten, G. (1997). Economic conditions, economic perceptions, and public support for European integration. Political Behavior, 19(1), 81–96.

Garrett, G. (2004). Globalization’s missing middle. Foreign Affairs, 83, 84–97.

Garuda, G. (2000). The distributional effects of IMF programs: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 28(6), 1031–1051.

Goldberg, P., & Pavcnik, N. (2005). Trade, wages, and the political economy of trade protection: Evidence from the Colombian Trade Reforms. Journal of International Economics, 66, 75–105.

Goldstein, J. (1996). International law and domestic institutions: Reconciling North American “Unfair” trade laws. International Organization, 50(4), 541–564.

Gray, M. M., Kittilson, M. C., & Sandholtz, W. (2006). Women and globalization: A study of 180 countries, 1975–2000. International Organization, 60, 293–333.

Haggard, S., & Kaufman, R. (1992). Institutions and economic adjustment. In S. Haggard & R. Kaufman (Eds.), The politics of economic adjustment, pp. 3–37. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Haggard, S., & Kaufman, R. R. (1995). The political economy of democratic transitions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hainmueller, J., & Hiscox, M. J. (2006). Learning to love globalization: Education and individual attitudes toward international trade. International Organization, 60, 469–498.

Hayo, B. (1999). Knowledge and attitude toward European Monetary Union. Journal of Policy Modeling, 21(5), 641–651.

Hayo, B., & Shin, D. C. (2002). Popular reaction to the intervention by the IMF in the Korean economic crisis. Journal of Policy Reform, 5(2), 89–100.

Hellman, J. (1998). Winners take all: The politics of post-communist reform in postcommunist transitions. World Politics, 50(2), 203–234.

Jusko, K. L., & Shively, W. P. (2005). Applying a two-step strategy to the analysis of cross-national public opinion data. Political Analysis, 13, 327–344.

Kaufman, R. R., & Zuckermann, L. (1998). Attitudes toward economic reform in Mexico: The role of political orientations. American Political Science Review, 92(2), 359–375.

Kinder, D., & Kiewiet, D. R. (1979). Economic discontent and political behavior: The role of personal grievances and collective economic judgments in congressional voting. American Journal of Political Science, 23, 495–527.

Kinder, D., & Kiewiet, D. R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science, 11, 129–145.

Lewis, J. B., & Linzer, D. A. (2005). Estimating regression models in which the dependent variable is based on estimates. Political Analysis, 13, 345–364.

Lewis-Beck, M. (1988). Economics and elections. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Mayda, A. M., & Rodrik, D. (2005). Why are some people (and countries) more protectionist than others? European Economic Review, 49, 1393–1430.

Mussa, M. L., & Savastano, M. A. (1999). The IMF approach to economic stabilization. IMF Working Paper 99/104.

Nsouli, S. N., Atoyan, R., & Mourmouras, A. (2006). Institutions, program implementation, and macroeconomic performance. In A. Mody & A. Rebucci (Eds.), IMF-Supported programs: Recent staff research. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Oatley, T., & Nabors, R. (1998). Redistributive cooperation: Market failure, wealth transfers, and the Basle accord. International Organization, 52(1), 35–54.

O’Brien, R., Goetz, A. M., Schole, J. A., & Williams, M. (2000). Contesting global governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Rourke, K. H., & Sinnott, R. (2001). The determinants of individual trade policy preferences: International survey evidence. Brookings Trade Forum.

Pastor, M. (1987). The effects of IMF programs in the third world: Evidence and debate from Latin America. World Development, 15(2), 249–262.

Przeworski, A. (1991). Democracy and the market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, A. (1996). Public support for economic reforms in Poland. Comparative Political Studies, 29, 520–544.

Rankin, D. M. (2001). Identities, interests, and imports. Political Behavior, 23, 351–376.

Rogowski, R. (1989). Commerce and coalitions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ruggie, J. G. (1982). International regimes, transactions and change: Embedded Liberalism in the postwar economic order. International Organization, 36(2), 379–415.

Scheve, K. F., & Slaughter, M. J. (2001). Globalization and the perceptions of American workers. Washington: Institute for International Economics.

Safa, H. I. (1999). Free markets and the marriage market: Structural adjustment, gender relations, and working conditions among Dominican women workers. Environment and Planning A, 31, 291–304.

Sparr, P. (1994). Mortgaging women’s lives: Feminist critiques of structural adjustment. London: Zed.

Stokes, S. (2001). Public support for market reforms in new democracies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stolper, W., & Samuelson, P. (1941). Protection and real wages. Review of Economic Studies, 9, 58–73.

Vaubel, R. (1991). The political economy of the international monetary fund: A public choice analysis. In R. Vaubel & T. D. Willett (Eds.), The political economy of international organizations, pp. 204–244. Boulder: Westview.

Vreeland, J. R. (2002). The effect of IMF programs on labor. World Development, 30(1), 121–139.

Vreeland, J. R. (2003). The IMF and economic development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Vreeland, J. R. (2006). IMF program compliance: Aggregate index versus policy-specific research strategies. Review of International Organizations, 1, 359–378.

Weyland, K. (1996). Risk-taking in Latin American economic restructuring. International Studies Quarterly, 40, 185–207.

World Bank. (1997). Adjustment lending in Sub-Saharan Africa: An update. World Bank Report No. 16594. Washington, D.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

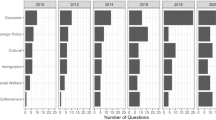

Appendix 1: List of Countries and Questions

Individual Level Model One (34 Countries): Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Cote d’Ivoire, Czech Republic, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Mali, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Senegal, Slovak Republic, South Africa, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Vietnam.

Individual Level Model Two (24 Countries): Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Mali, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, Uzbekistan, Venezuela.

Individual Level Model Three (14 Countries): Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Lebanon, Mali, Peru, Senegal, South Africa, Turkey, Venezuela.

1.1 Dependent Variable:

Here is a list of groups, organizations, and institutions. For each, please tell me what kind of influence the group is having on the way things are going in (survey country). Is the influence of international organizations like the IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization very good, somewhat good, somewhat bad or very bad in (survey country)?

1.2 Independent Variables:

Economic Situation: Now thinking about our economic situation, how would you describe the economic situation in (survey country) is it very good, somewhat good, somewhat bad or very bad?

Change in Economy: Over the next 12 months, do you expect the economic situation in our country to improve a lot, improve a little, remain the same, worsen a little, or worsen a lot?

Household Income: As I read each of the following, please tell me whether you are very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with this aspect of your life. Your household income?

Unemployment: What is your current employment situation? (Dummy variable created from all those who self identified as unemployed).

Education: What is the highest level of education that you have completed? (Responses on nine-point scale: No formal education, Incomplete primary education, Complete primary education, Incomplete secondary education (vocational school), Complete secondary education (vocational school), Incomplete secondary education (preparatory school), Complete secondary education (preparatory school), Some university, University graduate.

Ideology: Some people talk about politics in terms of left, center, and right. On a ten-point scale, with 1 indicating extreme left and 10 indicating extreme right, where would you place yourself?

Free Market Economy: Please tell me whether you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the following statement: “Most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some people are rich and some are poor.”

Consumerism: Which comes closer to your view? Consumerism and commercialism are a threat to our culture, or consumerism and commercialism are not a threat to our culture?

Foreign Influence: Here is a list of statements. For each one, tell me whether you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree, or completely disagree with it. Our way of life needs to be protected against foreign influence.

Appendix 2: Summary Statistics

Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

National Level Data | ||||

Net IBRD Lending per capita | 3.090624 | 6.862637 | −5.382596 | 17.52678 |

Net IMF Lending per capita | 34.99793 | 76.3888 | −21.18483 | 247.3083 |

Gross National Income per capita | 4310.646 | 3359.331 | 830 | 11440 |

Freedom House Score | 2.18781 | .6536976 | 1 | 3 |

Trade Dispute Count | 2.941823 | 5.594166 | 0 | 18 |

Gender Loans Count | 3.517959 | 3.401729 | 0 | 13 |

Individual Level Data | ||||

Opinion regarding IEOs | 2.208352 | .9774555 | 1 | 4 |

Economic Situation | 3.130802 | .841776 | 1 | 4 |

Change in Economy | 2.646443 | 1.128196 | 1 | 5 |

Gender | 1.459916 | .4984269 | 1 | 2 |

Household Income | 2.598283 | .9131254 | 1 | 4 |

Unemployment | .0854067 | .2795062 | 0 | 1 |

Education | 5.386731 | 2.337317 | 1 | 9 |

Ideology | 5.066056 | 2.356968 | 1 | 10 |

Free Market Economy | 2.214026 | 1.021607 | 1 | 4 |

Consumerism | 1.522334 | .5793826 | 1 | 4 |

Foreign Influence | 1.922159 | .9287288 | 1 | 4 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, M.S. Public support for the international economic organizations: Evidence from developing countries. Rev Int Organ 4, 185–209 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-009-9057-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-009-9057-6