Abstract

The introduction of well-adapted species, such as Trifolium subterraneum (subclover) and Poa pratensis (Kentucky bluegrass), might enhance the forage yield and quality of dehesa pastures for feeding livestock. However, the climatic hardness and poor soils in these agrosystems may limit plant establishment and development. Since fungal endophytes have been found to alleviate the environmental stresses of their host, the aim of this study was to assess the effect of five isolates on forage yield, nutritive value, and plant mineral uptake after their inoculation in the two abovementioned plant species. Two experiments were established (under greenhouse and field conditions) using plants inoculated with two isolates in 2012/2013 (Epicoccum nigrum, Sporormiella intermedia) and three isolates in 2013/2014 (Mucor hiemalis, Fusarium equiseti, Byssochlamys spectabilis). Fusarium equiseti (E346) increased the herbage yield of T. subterraneum under greenhouse conditions, and B. spectabilis improved the forage quality of T. subterraneum by reducing fiber content and of P. pratensis by increasing crude protein. S. intermedia increased the mineral uptake of Ca, Cu, Mn, Pb, Tl, and Zn in subclover, and M. hiemalis increased the uptake of K and Sr in Kentucky bluegrass. These results evidence the potential of the studied fungal endophytes to enhance herbage yield and nutritional value of forage, although further studies should include all of the target forage species as certain host specificity in the effect was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dehesas are Mediterranean agrosilvopastoral systems located mainly in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula, characterized by a steadiness between production and conservation (Moreno and Pulido 2009; Simón et al. 2013). Extensive livestock grazing is usually the main activity, and it plays a key role in the system by increasing forage yield and biodiversity of pastures (Pinto-Correia et al. 2011; López-Sánchez et al. 2016). However, dehesa productivity is frequently limited due to the harshness of the climate and the low quality of the soil (Olea and San Miguel-Ayanz 2006; Schnabel et al. 2013).

In this context, forage provided by natural grasslands may not be sufficient to satisfy the nutritional requirements of livestock in terms of quantity and quality. Under these conditions, the introduction (or, at least, the enhancement) of well-adapted species that can increase forage yield and improve the nutritive value of the herbage, might be a good strategy to cope with, or alleviate, this feeding deficiency. Traditionally, these introductions have been performed by using forage species of grasses and/or leguminous crops, such as Poa pratensis L. (P. pratensis, Poaceae, Poales, Kentucky bluegrass) and Trifolium subterraneum L. (T. subterraneum, Fabaceae, Fabales, subterranean clover), respectively. Kentucky bluegrass, a perennial pasture grass in Europe, is a very palatable and high-yielding plant, able to produce 4100- to 10,400-kg DM ha−1, depending on the environment, especially with rainfall (Dürr et al. 2005; Bender et al. 2006). On the other hand, subterranean clover, also called subclover, as naturally present in this ecosystem, is one of the key species due to its high quality and late senescence in the growing season (San Miguel 1994). For this reason, it is one of the most important legumes used in sown pastures in countries with temperate or Mediterranean climates, such as Spain (Frame et al. 1998). Moreover, subterranean clover is often used for the recovery of degraded pastures, to increase forage yield and prevent soil erosion (Crespo and Cordero 1998).

Although these two species present a certain hardiness which allows them to grow in the harsh climatic conditions and low soil fertility of this ecosystem, their establishment and performance may be limited, with decreased vegetative growth, forage yield, and herbage nutritive content (Bolger et al. 1993; Croce et al. 2001; Hodge 2004). However, plants are not isolated organisms, as they establish mutualistic or symbiotic relationships with other living forms such as fungi or bacteria which allow them to improve their performance under unfavorable conditions. Therefore, the utilization of such organisms could be a good strategy to enhance their development under the semiarid conditions of the dehesas. Within those associations, fungal endophytes are organisms that may spend their life cycle inside the host plant tissues without causing symptoms of disease (Rodriguez et al. 2009). These fungi can confer adaptive advantages to host plants by improving their stress tolerance or by protecting them against grazing, pests, and diseases, resulting in better plant growth and consequently a greater herbage yield (Ismail et al. 2018). Fungal endophytes can increase water and nutrient uptake by plant hosts (Schardl et al. 2008), and enhance plant resistance against biotic and abiotic stresses, such as salt accumulation and drought (Moghaddam et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2021). The capacity of endophytes to induce an increase in mineral uptake by host plants (García-Latorre et al. 2021) has also been used for the detoxification of contaminated soils with heavy metals like Ni (Ważny et al., 2021).

Endophytic fungi have also been reported to produce phytohormone-like substances, particularly gibberellins (GAs) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) which can both enhance plant vegetative growth and help plant hosts to protect them against the harmful effects of abiotic stresses (Waqas et al., 2015; Ismail et al. 2021). Thus, the possibility of using these phytohormone-like substances produced by endophytes as plant growth promoters may lead to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly agriculture. Furthermore, in a climate change scenario, where a decrease in rainfall is expected in Mediterranean areas (Bilal et al. 2018), the use of these endophytes or their metabolites may contribute to mitigate its effects by maintaining an acceptable level of forage yield with lower precipitation, as well as reducing the use of synthetic chemical fertilizers.

Correctly evaluated, optimization of the plant-endophyte interaction may become an important pathway to increase productivity, since these effects could be achieved in a wide variety of plant species (Rodriguez et al. 2008; Redman et al. 2011). However, the effect of an endophyte on a particular plant host may be variable (Bastías et al. 2021) depending on the endophytic species, the host genotype, and the environmental conditions (Ahlholm et al. 2002). Consequently, the particular outcomes of the association between specific fungal symbionts and plants should be conveniently outlined in order to obtain the widest range of application. This would be particularly important in natural grasslands, such as dehesas, and other polyculture systems, where the specific variability of plants is relatively high, and where not very closely related species, such as grasses and leguminous species, co-occur.

Several studies concerning the effect of endophytes on a single pasture host under the same environmental conditions have already been conducted on P. pratensis (Lledó et al. 2015), T. subterraneum (Lledó et al. 2016a), and on another legume species, Ornithopus compressus (O. compressus, Fabaceae, Fabales; Santamaria et al. 2017), but they were carried out with a different set of fungal endophytes, and the effect of the host was not considered. Therefore, in order to find a wider number of fungal endophytes with positive effects on the general performance of plant hosts and at the same time to evaluate the specificity of these eventual effects, the objective of the present study was to assess the effect of artificial inoculation with each of five different species of non-clavicipitaceous endophytes on forage yield (herbage and root biomass), quality traits, and nutrient uptake on two important and not very taxonomically related forage crops, i.e., a leguminous species (T. subterraneum) and a gramineous species (P. pratensis).

Material and methods

Fungal and plant material

Five fungal endophytes (Table 1), previously isolated from different pasture species of dehesas in Extremadura (Southwest of Spain), were used for the inoculations. These fungi were selected because they had already been shown to produce some kind of plant promotion or plant protection in other hosts (Rodrigo et al. 2017, 2018; Santamaria et al. 2017). These endophytes had been previously identified by morphological characteristics (several morphological features are shown in Appendix A, Fig. S1), when possible, and by the comparison of the ITS region sequence with sequences from EMBL/GenBank (www.NCBI.nlm.nih.gov) and UNITE (https://unite.ut.ee. Version 8.3; Kõljalg et al. 2020) databases using a BLAST search. A more detailed explanation of how the species assignation was made when multiple accessions or ambiguous results were found, and other aspects about identification, can be obtained from Lledó et al. (2016b) and Santamaria et al. (2018).

The experiments were carried out over 2 years, in 2012/2013 with two of the endophytes: Epicoccum nigrum (E. nigrum, Didymellaceae, Pleosporales; E179) and Sporormiella intermedia (S. intermedia, Sporormiaceae, Pleosporales; E636), and in 2013/2014 with the rest of the endophytes: Mucor hiemalis (M. hiemalis, Mucoraceae, Mucorales; E063), Fusarium equiseti (F. equiseti, Nectriaceae, Hypocreales; E346), and Byssochlamys spectabilis (B. spectabilis, Aspergillaceae, Eurotiales; E408). In both study years, in order to obtain sufficient inoculum for the plant inoculations, active mycelium from each fungus was grown at 25 °C in 1.5-L flasks containing 1 L of potato dextrose broth (PDB). The flasks were kept in the dark for 2 months before inoculation, shaken manually for 5 min every 3 days in order to stimulate the fungal growth.

Inoculations were carried out in 2-month old seedlings of T. subterraneum cv “Valmoreno” and P. pratensis cv “Sobra.” To obtain the plant seedlings, seeds of each species were first surface-disinfected by immersion for 5 and 2 min, respectively, in 2.5% NaClO, followed by three washes with sterilized distilled water. Five individual surface-sterilized seeds per plant species (N = 10 total samples) were randomly selected and imprinted onto fresh potato dextrose agar (PDA, Scharlau, Spain) as a way to verify surface sterilization efficiency, and no outgrowing fungal colonies were observed. After that, five sterilized seeds per pot for T. subterraneum and ten seeds for P. pratensis were sown in 7 × 7 × 6-cm plastic pots containing autoclaved (twice for 1 h at 121 °C) soil substrate consisting of a 1:1 (vol/vol) mix of perlite and a commercial growing medium composed of peat, perlite, lime, root activator, and fertilizer NPK (COMPO SANA Universal, COMPO GmbH & Co. KG, Münster Germany). The substrate characteristics (Table 2) were calculated on four homogenized samples as follows: Electrical conductivity (EC) was determined using an EC-meter, and pH, using a calibrated pH meter (ratio 10 g soil: 25 ml deionized H2O). Total N was determined using the Kjeldahl method (Bremner 1996), by means of a Kjeltec™ K350 distillation Unit (Buchi Ltd., Flawil, Switzerland). Extractable P was determined by the Olsen procedure, and Ca and K were extracted with ammonium acetate (1 N) and quantified by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Helyos alpha, 9423-UVA, Unicam, Cambridge, UK). Total Al, B, Ca, Cu, Fe, K, Li, Mg, Mn, Mo, Na, P, Pb, S, Se, and Zn concentrations were determined by the Ionomics Service of CSIC (Spanish High Centre for Science and Research) by means of inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). An approximation to the normal range of each nutrient in soils for the pasture growth is also shown in Table 2. In general, values were within the range; and when this was not the case, the values were not considered sufficient to cause toxicity in the plant (Reid and Dirou 2004; Hazelton and Murphy 2016).

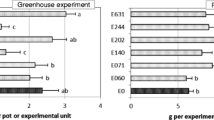

The sowing date was in early December in both study years. After that, pots were placed in a greenhouse and watered to field capacity every 2 to 3 days. Environmental conditions in the greenhouse, such as maximum and minimum temperatures and relative humidity, were monitored throughout the duration of the experiment (Fig. 1).

Before endophyte inoculation, plants were treated three times with a systemic fungicide, Amistar Xtra® (20 g of Azoxystrobin and 8 g of cyproconazole each 5 L; Syngenta, Madrid, Spain). The aim of this treatment was to remove any pre-existing fungus within the plant that could limit the colonization of our selected strains or interact somehow with them, thereby altering the results. Thus, the first treatment was made when plants were 1 month old, and again every 10 days as a foliar spray (approx. 1 mL per pot of a dilution of 1-mL fungicide in 1 L distilled water). With the third application, 1 mL of fungicide solution was also added to the soil substrate in each pot. Effectiveness of the fungicide treatment was evaluated just before inoculations by taking randomly four plants and analyzing them in the laboratory. Five-millimeters-long segments were cut from different parts of each plant, surface disinfected, and placed on PDA amended with 50-mg L−1 chloramphenicol (to avoid bacteria development) in a Petri dish. After 2 months of incubation at 25 °C in the dark, no colonies of fungi were observed growing out of any of the plant segments.

Inoculations

Inoculations were performed 5 weeks after the last fungicide application. Just before inoculations, plants were wounded by using a hand-made tool to puncture their leaves and stems in order to facilitate fungal infection without serious plant damage. Then, a homogenized blended mix of inoculum was applied by means of a hand sprayer to all the plants in two doses: one dose just after plant wounding, and the second 3 days later. The inoculated seedlings were then maintained in a high humidity atmosphere for 48 h after the application in order to favor infections. The viability of the mycelium after blending was evaluated in vitro, by verifying the growth of new colonies on Petri dishes containing PDA sprayed with the blended mix. Ten pots or experimental units (containing five plants each in the case of T. subterraneum and 10 plants in the case of P. pratensis) were inoculated with each of the endophytes. Ten additional pots or experimental units were inoculated only with culture medium to be used as control. Each plant received a different amount of mycelia depending on the endophytic species inoculated due to their different growth rate: E063 (M. hiemalis) 74.0 mg plant−1, E179 (E. nigrum) 274.0 mg plant−1, E346 (F. equiseti) 134.0 mg plant−1, E408 (B. spectabilis) 63.8 mg plant−1, and E636 (S. intermedia) 282.6 mg plant−1.

In order to check the effectiveness of the inoculations, plant samples of each treatment were taken to the laboratory approximately 1 month after inoculating for re-isolation, which was performed with the same procedure used to evaluate the effectiveness of the systemic fungicide described above. After the re-isolation process, the five endophytes were positively re-isolated and identified in culture medium. This could mean that the inoculation method was sufficiently effective to cause infection, and consequently the differences observed between treatments could be attributed to the inoculation.

Each year, half of the pots containing inoculated plants were kept in the greenhouse (i.e., a total of 60 pots for each plant host), arranged on benches following a completely randomized design, separated at least 5 cm apart to avoid cross-contamination. Plants were watered to field capacity every 2 to 3 days. In order to evaluate the potential pathogenic behavior of the endophytes used in the present study on the studied hosts, these plants were visually examined five times every 3 weeks (starting 3 weeks after inoculation) to check for disease symptoms (yellowing, drying, rotting leaves, blackish spots, etc.). Depending on the severity of these symptoms, on average, the plants in each pot were assigned to a category on the following scale: 1 = healthy, 2 = slightly affected, 3 = moderately affected, 4 = severely affected, and 5 = dead. Disease progress curves for each pot were constructed by plotting the values of disease severity over time. The area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated as the sum of the area of the corresponding trapezoids, considering one unit per period between two consecutive measurements. The AUDPC was used as response variable to evaluate disease severity. Three months after inoculations, herbage and roots were harvested and taken to the laboratory for processing.

To evaluate the consistency of the eventual effects caused by the endophytes on the host plants, given that they have been shown to be dependent on environmental conditions (Ahlholm et al. 2002), the second half of the pots (the remaining five repetitions) were transported to the field in March, approximately 1 month after the inoculations. In 2012/2013, only plants of T. subterraneum could be transplanted in the field, while in 2013/2014, plants of both species were used for this part of the assay. In both years, the experimental area was in the Dehesa Valdesequera, owned by the regional government of Extremadura and located in Badajoz, south-west Spain (UTM Coordinates, Zone 29 North Datum: X = 685,365 m; Y = 4,325,603). Four soil samples 30 cm deep of the experimental area were taken to the laboratory to determine their properties by using the same procedures as for the substrate. The values can be observed in Table 2. Climatic data during the experiment, which were taken from a weather station located close to the study site, are shown in Fig. 1. Before transplanting, in late February of each year, conventional tillage was applied to prepare an appropriate environment for plants. The experimental units (a set of five plants) were arranged by using a randomized design with a planting layout of 50 cm × 50 cm. After transplanting, seedlings were maintained without further fertilization or irrigation. Two months and a half after transplanting, herbage was harvested and taken to the laboratory for processing.

Yield and quality determinations

After harvesting, plant samples were oven dried at 70 °C until constant weight for dry matter (DM) of herbage and root biomass (from greenhouse) determination. The dried samples, after grinding, were also used to determine the main quality parameters. Thus, total N content was analyzed by the Kjeldahl method (Kjeltec™ 8200 Auto Distillation Unit. FOSS Analytical. Hilleroed, Denmark) and used to estimate crude protein (CP) by multiplying the biomass N by 6.25 (Sosulski and Imafidon, 1990). Official procedures (AOCS 2006) were followed to determine neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) by means of a fiber analyzer (ANKOM8– 98, ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY). Total ash content was determined by ignition of the sample in a muffle furnace at 600 °C, according to the official procedure (AOCS 2006). An aliquot of each sample was sent to the Ionomics Service of CSIC (Spanish High Centre for Science and Research) for mineral determinations with an ICP-OES as explained for the soil samples. The mineral content was determined in 2012/2013 for both greenhouse and field samples but only for the field samples in 2013/2014.

Statistical analysis

The effect of the endophyte inoculation (three treatments, including controls in 2012/2013, and four treatments, including controls in 2013/2014), plant host (T. subterraneum and P. pratensis), and their interaction, was evaluated on disease severity (estimated as the area under the disease progress curve, AUDCP), herbage dry matter (HDM and FDM for the greenhouse and field experiment respectively), root dry matter (RDM; only in the greenhouse experiment), nutritive value parameters (CP, NDF, ADF, ADL, and ashes), and mineral concentration by means of two-way ANOVAs. A Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) test for multiple comparison was used when significant differences (P < 0.05) were found in the ANOVA. In order to normalize the variable distribution as well as to stabilize the variance of residues, the transformation 5√x was performed for HDM, RDM, and NDF. For NDF, the transformation was applied in both field and greenhouse values. In any case, untransformed values for these three parameters are shown in tables and figures, for clarification. The rest of the variables were analyzed using the original data. All the analyses were performed with the Statistix v. 8.10 package (Analitical Software, USA).

Results

Effects of endophytes on disease severity, biomass yield, quality parameters, and mineral content in the greenhouse experiment

Although the area under the disease progress curve (AUDCP) was significantly affected by the endophyte treatment in 2012/2013 (Table 3), none of the endophytes caused greater disease severity in comparison with controls. In fact, plants inoculated with the endophyte E179 (E. nigrum) showed healthier values than those observed in controls (mean values ± standard error [n = 10]: 6.00 ± 0.42 for E636, 5.75 ± 0.27 for controls, and 4.95 ± 0.13 for E179). Regarding biomass yield, even when in both study years the inoculation with an endophyte significantly affected the herbage dry matter (HDM; Table 3), in 2012/2013, such an effect depended on the plant host, as their interaction was also significant (P < 0.05). Considering the endophyte inoculation as main effect, neither HDM nor RDM (root dry matter) were increased by any of the endophytes in the two-study years compared with the non-inoculated plants. Conversely, the plants inoculated with endophyte E063 or E408 showed a significant decrement in RDM in 2013/2014 in relation with controls (Fig. 2a) of about 11% and 14%, respectively.

Effect of a endophyte inoculation and b endophyte × host interaction on biomass yield (herbage dry matter in the field: FDM, herbage dry matter in the greenhouse: HDM, and root dry matter in the greenhouse: RDM) in both years of study. Untransformed data is shown. Charts indicate means (n = 5) and error bars indicate standard error. Within each analysis, parameter and year, different letters represent significant differences between means according to LSD tests (p ≤ 0.05). In order to make the differences clearer, a different set of letters was assigned to each case (lowercase letters for HDM in 2012/13, Greek letters for HDM in 2013/14, and uppercase letters for RDM in both years. E0 (control), E063 (Mucor hiemalis), E179 (Epicoccum nigrum), E346 (Fusarium equiseti), E408 (Byssochlamys spectabilis, and E636 (Sporormiella intermedia)

When the interaction “inoculated endophyte*host” was analyzed (Fig. 2b), significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) in herbage and root biomass yield of the host caused by inoculation were only found in T. subterraneum. For that host, in 2012/2013, with regard to HDM, such differences were negative, as the inoculation with endophyte E636 caused a decrease of around 36% in herbage dry matter in comparison with control plants (Fig. 2b). During 2013/2014, however, inoculation of subclover with E346 did increase herbage biomass with respect to their control. In relation to RDM, none of the endophytes increased significantly root biomass yield in plants of T. subterraneum when compared with non-inoculated plants (Fig. 2b).

In general, the influence of endophyte inoculation on nutritional quality traits was rather limited. In 2012/2013, a significant influence of the endophyte, in terms of either main effect or the interaction with the host, was only found for acid detergent fiber (ADF) and ash content in herbage, respectively (Table 3). In this case, the endophyte E636 caused a decrease of 9.3% in the ADF percentage in comparison with control (Fig. 3c). Regarding ash content, inoculation, with either endophyte E179 or E636, produced plants with significantly lower values for T. subterraneum, 0.26% and 0.27%, respectively, in comparison with controls, which was 0.43%. No differences were observed for P. pratensis for this parameter. In 2013/2014, interaction between endophyte inoculation and plant host species significantly affected NDF. Thus, inoculation with E408 (B. spectabilis) caused a decrement of 10% in the plants of T. subterraneum with respect to the uninoculated ones (Fig. 3b).

Effect of the interaction between endophyte inoculation and plant host on a crude protein (CP) in the field experiment in 2013/2014; b neutral detergent fiber (NDF) in the greenhouse in 2013/2014 (untransformed data for this parameter is shown). Effect of endophyte inoculation on c acid detergent fiber (ADF), and d acid detergent lignin (ADL) in the greenhouse and field experiments in both study years. Vertical charts indicate means (n = 3) and error bars, standard errors. For each parameter and year, different letters were assigned when significant differences were found according to LSD tests (p ≤ 0.05). In order to make the differences clearer, a distinct set of letters (lowercase, uppercase, and Greek letters) was assigned to each parameter. E0 (control), E063 (Mucor hiemalis), E179 (Epicoccum nigrum), E346 (Fusarium equiseti), E408 (Byssochlamys spectabilis), and E636 (Sporormiella intermedia)

Regarding nutrient uptake, only the main significant effects of endophyte inoculation on the concentration of minerals in herbage are shown in Table 4 (the full set of results can be found in Appendix A, Table S1). Thus, results in the greenhouse showed that fungal inoculation affected plant uptake of Ca, Cr, Mo, Na, Pb, and Tl, when considered as main effect, and Ca, Cr, Cu, Mn, Na, P, Pb, S, Ti, Tl, and Zn, when considering its interaction with the plant host. Inoculation with S. intermedia (E636) caused a significant increase in uptake of Ca, Cu, Mn, Pb, Tl, and Zn by the plants of T. subterraneum and a decrease in uptake of Cr in this same host plant (Table 4). Conversely, inoculation with E. nigrum (E179) significantly decreased uptake (down to 3.8 times) of Ti by plants of T. subterraneum. Inoculation with both endophytes caused a decrease in uptake of Cr (− 57.30% for E179 and − 73.94% for E636) and S (− 40.46% and − 37.40%, respectively) in plants of P. pratensis (Appendix A, Table S1).

Effects of endophytes on biomass yield, quality parameters, and mineral content in the field experiment

Results from the field experiment showed no significant effect of endophyte inoculation on herbage yield in either of the years (Table 2). Field dry matter (FDM) for T. subterraneum ranged from 4.18 g unit−1 in the control to 5.23 g unit−1 when E179 was inoculated in 2012/2013, and from 15.72 to 17.88 g unit−1 when E179 and E346 were inoculated in 2013/2014, respectively. In the case of P. pratensis, FDM ranged from 1.59 to 2.27 g unit−1 when E346 and E408 were inoculated in 2013/2014 (Fig. 1a).

Fungal inoculation influenced (P < 0.05), as main effect, herbage quality traits in terms of ADF and ADL in the first year (2013/2014). Crude protein (CP) was also affected by fungal inoculation in 2013/2014, but only when considering interaction with the host. In 2012/2013, inoculation with E636 increased the ADF content in herbage by around 15% and ADL by around 79.06% with respect to the control (Fig. 3c, d). On the other hand, in 2013/2014, when the interaction ‘inoculated endophyte*plant host’ was analyzed, it was observed that inoculation with the endophyte E346 (F. equiseti) caused a decrease in protein content from 17.75 to 15.70%, but only in T. subterraneum. The same effect was observed when B. spectabilis (E408) was inoculated in the same host, although this response was completely the opposite when it was inoculated in P. pratensis, with an increase in crude protein content of around 9% (Fig. 3a).

In relation to the influence of endophyte inoculation on mineral accumulation in herbage, the main significant results are shown in Table 5 (the full set of results can be found in Appendix A, Table S2). In 2012/2013, uptake of Cu, P, Tl, and Zn by T. subterraneum (the only species in the field experiment during that year) was significantly affected by inoculation with the endophyte E636, causing a lower uptake of P (− 33.33%) and Zn (− 23.51%) but increasing uptake of Tl by 45% (Appendix A; Table S2). In 2013/2014, uptake of B, Cu, Na, S, and Zn was significantly affected by endophyte inoculation when it was considered as main effect (Table 5), and uptake of B, Cr, K, Mg, and Sr was affected by the interaction “inoculated endophyte*plant host.” Inoculation with E063 increased uptake of B (+ 14.79%) and Na (+ 20.69%) on average, while plants inoculated with E408 presented higher concentrations of B, Cu, Na, S, and Zn, by 13.29%, 14.11%, 10.34%, 14.29%, and 17.68%, respectively.

Considering the interaction “inoculated endophyte*plant host,” uptake of B was significantly increased by inoculation with E063 (+ 26.73%) and E408 (+ 19.74%) only in T. subterraneum (Table 5). Inoculation with E063 also increased Trifolium uptake of Cr by 75%, while inoculation with E408 caused an increase in uptake of Cr, K, Mg, and Sr (33.71%, 12%, 16.67%, and 18.82%, respectively) in P. pratensis. Finally, plants of P. pratensis inoculated with E346 presented a higher concentration of K (+ 10%) and Sr (+ 18.82%) in relation with controls (Table 5).

Discussion

The effectiveness of the artificial inoculations was confirmed by the fact that the five fungi used were successfully re-isolated from the inner tissues of host plants. It may therefore be reasonable to suggest that the selected endophytes colonized the internal tissues of both pasture species, T. subterraneum and P. pratensis; and consequently, the different effects found on the parameters analyzed after inoculations could be mainly attributed to the inoculated endophyte. In addition, no other colony was re-isolated from any of the plant samples after fungicide application. Consequently, the influence of the naturally occurring microbiome in the plant could be considered almost negligible, eliminating any interaction with the inoculated organisms or cross-effects which could bias the results. The eventual influence of other organisms, such as endophytic bacteria, was not considered in the present study on the hypothesis that the degree of interaction between those two unrelated groups would likely be low. In fact, chloramphenicol was used in culture media to limit the bacteria development, but their occurrence in plants may of course be very plausible. Nevertheless, further studies should include this interaction with natural populations of bacteria and endophytic fungi to establish the real influence of these other microorganisms groups in the response given by our fungal endophytes.

It is also important to note that the experiment was first performed in the greenhouse in order to assess endophyte behavior under the most standard and controlled conditions as possible, thus reducing the number of variables that could affect their performance. Nevertheless, once the influence of endophyte inoculation on the studied parameters can be demonstrated under these conditions, it may also be important to evaluate it under field conditions in order to test their consistency, as it is known that endophytes performance is clearly dependent on environmental conditions (Ahlholm et al. 2002). In this case, during the study years, in the field, the relatively high temperatures and low rainfall during April and May may have caused stress factors for plants. This should be taken into account in the interpretation of the results as it is known that fungal endophytes often improve performance in plants subjected to biotic or abiotic stresses (Assuero et al. 2006).

According to the evaluation of the disease incidence shown by the endophytes studied, none of the isolates produced any external signs of disease, at least in the duration of the experiment. Therefore, their potential to act as pathogens could be ruled out, thus validating the premise of their role as endophytes. This aspect was supported by the fact that all of them have been previously described as endophytes (Maciá-Vicente et al. 2009; Oliveira Silva et al. 2009; Leyte-Lugo et al. 2013; Perveen et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2017). This is an important issue in regard to the use of the studied endophytes in eventual future applications as plant growth promoters or as biological agents to improve performance of forage crops or the nutritional quality of their herbage. Nevertheless, further studies, including the evaluation of endophyte production of eventual toxic compounds for livestock, should be performed before endophyte-based products are used commercially.

Regarding herbage yield, although inoculations did not have an effect on herbage biomass in P. pratensis when compared to the control, inoculation with the endophyte E636 (identified as S. intermedia) produced a decrease in herbage yield in T. Subterraneum in relation to controls under greenhouse conditions. Similar results were found by Newcombe et al. (2016) with different Sporormiella species in which the herbage yield of Bromus tectorum L (Poaceae, Poales) was reduced. Inoculation with endophyte E408 (B. spectabilis) also caused a significant decrement in biomass yield in RDM in comparison with controls of about 14%. This result was completely contrary to that obtained in the study conducted by Santamaria et al. (2018), in which inoculation with the same strain of this endophyte, caused an increment of ~ 42% in herbage yield of O. compressus with respect to the control under exactly the same in-field conditions. This fact might reveal that the effect of endophytes on plant growth may not only be dependent on the fungal species inoculated, as has been previously stated (Ismail et al. 2018), but also on the plant host where it is inoculated and the interaction that it establishes with the fungus.

It seems clear, therefore, that expression of the effect caused by the endophyte may be influenced by its host preference. The meta-analysis carried out by Mayerhofer et al. (2013) showed that the effect of an endophyte inoculation on root biomass tends to be positive when the fungus had been isolated from the same host species and negative or neutral otherwise. This analysis may be corroborated in our study by several findings. For example, M. hiemalis (E063), which had a negative effect on the root biomass, which was much more pronounced in T subterraneum, had originally been isolated from Poa annua (Poaceae, Poales), a strongly taxonomically related species to the P. pratensis used in the experiments. This inconsistency in the observed effect could be due to a different nature of the interaction fungus*plant host, playing a role as endophyte in some cases and as pathogen in others. Although the pathogenic role may be quite secondary in this case given that no disease symptoms were observed during the experiment, it might have been responsible for the decrease in biomass yield. This different behavior of fungi, playing a role of endophyte or pathogen depending on the plant host, has been already reported in several cases (Brader et al. 2017). Further studies should be carried out to understand the mechanisms involved in this different behavior.

Conversely, inoculation with F. equiseti (E346) produced an increase of about 13% in herbage yield of T. subterraneum under greenhouse conditions, and a positive trend (although not significant) in this sense in the field experiment. This fungus has already been considered as a plant growth promoter by Hyakumachi and Kubota (2003), perhaps by inducing resistance to host plants against diseases (Horinouchi et al. 2008). By improving the general health status of the plant, the endophyte could confer a better performance, being able thus to increase biomass yield. Since in our experiments no symptoms of disease were observed in any of the plants, other mechanisms may have acted to explain this increase in plant growth. Further experiments would need to be performed to elucidate such mechanisms.

Regarding the quality parameters of the forage, in the greenhouse, none of the endophytes significantly affected protein level. Neutral and acidic detergent fiber (NDF and ADF) contents decreased in plants of T. subterraneum inoculated with B. spectabilis (E408) and S. intermedia (E636), respectively. NDF and ADF contain mostly cellulose and lignin, which are mostly indigestible by non-ruminants (Newman and Newman 1992). Consequently, a decrease in fiber content caused by the endophyte could be considered as positive, from the point of view of animal nutritional value, as it may imply an increase in forage digestibility. Soto-Barajas et al. (2016)found significant variations in NDF and lignin content for Lolium perenne (L. perenne, Poaceae, Poales) when Epichloë endophytes were inoculated, but not in ADF. However, Rodrigo et al. (2017) did not find differences in fiber content of Lolium rigidum (Poaceae, Poales) forage when plants were inoculated with the endophyte E408. Once again, the influence of the host preference and the specific interaction endophyte-plant host might have determined the observed response.

Rasmussen et al. (2012) reported that infection of L. perenne with Neotyphodium lolii (Clavicipitaceae, Hypocreales) entailed an “upregulation of fungal cell wall hydrolases”, which could explain the reduction of the fiber content. Also, some endophytes can synthetize 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase (Zabalgogeazcoa et al. 2006; Chaturvedi and Singh 2016; Ali et al. 2019), the immediate precursor of ethylene in plants. These molecules could delay maturity of the plant, prolonging its vegetative growth stage (Santamaria et al. 2018). Thus, endophytes could act as a plant-growth cycle regulator. Considering that fiber content increases with the growth stage of the plant (Santamaria et al. 2014), such a delay caused by the endophyte may produce a lower fiber content, thus improving forage digestibility.

The interpretation of this effect becomes more complicated when the results of the in-field experiment are also considered, because in this case, inoculation with E636 caused the opposite effect regarding ADF, and also increased ADL in relation to controls. This could be explained if the production of the phytohormone-like substances by endophytes, with effects on the life cycle of the plant indicated above, may be modulated by environmental conditions. Thus, considering that plants and their endophytes prioritize their survival over growth (Nanda et al. 2019), under the favorable environmental conditions of the greenhouse, the endophyte might respond by producing substances which may enlarge cycle length. However, in the field, the endophyte may somehow detect the high temperatures registered during the 2012/2013 growing season, and respond by producing phytohormone-like substances which could shorten the vegetative stage of the plant, thus increasing cellulose and lignin content and decreasing protein content in the forage, such as has been indicated previously (Santamaria et al., 2014). The same fact might explain the lower protein content of the plants of T. subterraneum inoculated with endophytes E346 and E408, during 2013/2014.

These facts may impact negatively on the suitability of an eventual application of these fungi in this forage crop, especially when considered for cattle feeding, given that crude protein is one of the main nutritive quality parameters of forage. However, once again, the effect depended on the combination “endophyte*host*environment,” as the inoculation with the endophyte E408 (B. spectabilis) caused the opposite effect on P. pratensis, increasing the crude protein of the forage under in-field conditions. This lack of consistency in the effect of endophytes on crude protein content of forage is found in many studies in which the results are different in each case, such as those by Santamaria et al. (2018) or Rasmussen et al. (2007).

Regarding nutrient uptake, inoculation with E. nigrum (E179) caused a lower accumulation of Cr, as well as S in the forage of P. pratensis and of Ti in the forage of T. subterraneum in the greenhouse experiment. This effect can be considered negative as Cr and S are essential nutrients for plants and animals. The role of Ti is perhaps less clear, since it can improve plant growth, but higher concentrations might negatively affect the uptake of Fe (Cigler et al. 2010; Lyu et al. 2017), although such a situation did not happen in our case. However, inoculation with this endophyte did not alter the mineral content of T. subterraneum in the field experiment, probably because the effect on plant uptake may be related to the concentrations in the soil. Thus, in the cases where the mineral concentration in the soil/substrate is not a limiting factor, the effect may go unnoticed.

The effect of inoculation with the endophyte S. intermedia (E636) in the greenhouse trial was heterogeneous, as it increased the content of essential nutrients such as the overall uptake of Ca and Mn and Zn in T. subterraneum, but it also reduced the overall Cr, Mo and Na, and the Ti content in P. pratensis. However, the main problem found with inoculation with this endophyte was the increase in Pb uptake, which is especially important in the case of subterranean clover, as it could inhibit uptake and translocation of other mineral ions (Lamhamdi et al. 2013). Nevertheless, although this situation might imply the unsuitability of this fungus for its use in a livestock feeding system, it could be successfully used for other applications such as phytoremediation of lead in polluted soils due to mining activity for instance. In any case, further studies should be made to assess the viability of this option since this effect was not observed in the field experiment.

During 2013/2014, the effect on the accumulation of mineral content in the forage was in general more positive than in the previous year. Thus, M. hiemalis (E063) increased the overall uptake of B, Na, and Cr in the case of T. subterraneum. Tewari et al. (2005) have already described the capacity of this endophyte for the extraction of Cr(VI) from substrate by biosorption. Thus, this endophyte may increase the concentration of an essential nutrient for both plants and animals in forage by binding it to the T. subterraneum biomass. Finally, inoculation with the endophyte E408 significantly increased the general concentration of B, Cu, Na, S, and Zn in the forage of both host species, as well as the accumulation of Cr, K, Mg, and Sr in the forage of P. pratensis. Although all of these minerals are essential nutrients for plants and animals, the increase of Zinc is of special relevance since Zn deficiency affects more than 20% of the world’s population, Zn deficiency being one of the most important factors causing disease or death in the world (Sauer et al. 2016). This deficiency is mainly due to poor zinc concentration in many soils of the world, including those of the present study, which limits adequate Zn levels in food, main route of Zn supply to humans and animals (Hotz and Brown 2004). Thus, both endophytes, E346 and E408, which caused an increase in Zinc uptake and later accumulation in forage, could be further studied to act as Zn accumulators in plants once inoculated, to be used in biofortification programs of crops growing in Zn-deficient soils.

In conclusion, the results of this study show the capacity of endophytes to affect yield and quality parameters of pasture species. Thus, F. equiseti (E346) increased herbage yield, and B. spectabilis (E408) improved forage quality of T. subterraneum. Conversely, S. intermedia (E636) caused an increase in uptake of minerals such as Ca, Cu, Mn, Pb, Tl, and Zn and total ash content. Nevertheless, the considerable influence of the interaction between a fungal strain and its host species has been clearly evidenced as the results obtained were completely different for T. subterraneum and P. pratensis. However, further research is still needed to clarify the mechanisms that affect this interaction in order to optimize its agricultural application.

Data availability

Associated data to this manuscript has not been deposited.

Code availability.

Not applicable.

Change history

28 February 2022

The original version of this paper was updated to add the missing compact agreement Open Access funding note.

References

Ahlholm JU, Helander M, Lehtimäki S, Wäli P, Saikkonen K (2002) Vertically transmitted fungal endophytes: different responses of host-parasite systems to environmental conditions. Oikos 99:173–183

Ali S, Khan SA, Hamayun M, Iqbal A, Khan AL, Hussain A, Shah M (2019) Endophytic fungi from Caralluma acutangula can secrete plant growth-promoting enzymes. Fresenius Environ Bull 28:2688–2696

AOCS (2006) Official methods of analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington DC

Assuero SG, Tognetti JA, Colabelli MR, Agnusdei MG, Petroni EC, Posse MA (2006) Endophyte infection accelerates morpho-physiological responses to water deficit in tall fescue. New Zeal J Agric Res 49:359–370

Bastías DA, Gianoli E, Gundel PE (2021) Fungal endophytes can eliminate the plant growth–defence trade-off. New Phytol 230:2105–2113

Bender J, Muntifering RB, Lin JC, Weigel HJ (2006) Growth and nutritive quality of Poa pratensis as influenced by ozone and competition. Environ Pollut 142:109–115

Bilal L, Asaf S, Hamayun M, Gul H, Iqbal A, Ullah I, Lee IJ, Hussain A (2018) Plant growth promoting endophytic fungi Aspergillus fumigatus TS1 and Fusarium proliferatum BRL1 produce gibberellins and regulates plant endogenous hormones. Symbiosis 76:117–127

Bolger TP, Turner NC, Leach BJ (1993) Water use and productivity of annual legume-based pasture systems in the south-west of Western Australia. In: Baker MJ (ed) Proceedings of the XVII International Grassland Congress. New Zealand Grassland Association, Palmerston North, pp 274–275

Brader G, Compant S, Vescio K, Mitter B, Trognitz F, Ma L-J, Sessitsch A (2017) Ecology and genomic insights into plant-pathogenic and plant-nonpathogenic endophytes. Annu Rev Phytopathol 55:61–83

Bremner JM (1996) Nitrogen total. In: Sparks DL (ed) Methods of soil analysis, Part 3: chemical methods. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, pp 1085–1121

Chaturvedi H, Singh V (2016) Potential of bacterial endophytes as plant growth promoting factors. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 7:1–6

Cigler P, Olejnickova J, Hruby M, Csefalvay L, Peterka J, Kuzel S (2010) Interactions between iron and titanium metabolism in spinach: a chlorophyll fluorescence study in hydropony. J Plant Physiol 167:1592–1597

Crespo M, Cordero S (1998) Productividad y persistencia de ecotipos autóctonos de trébol subterráneo de la dehesa salmantina en condiciones de pastoreo. Pastos 28:89–95

Croce P, De Luca A, Mocioni M, Volterrani M, Beard JB (2001) Warm-season turfgrass species and cultivar characterizations for a Mediterranean climate. Int Turfgrass Soc Res J 9:855–859

Dürr G, Kunelius HT, Drapeau R, McRae KB, Fillmore SAE (2005) Herbage yield and composition of Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) cultivars under two harvest systems. Can J Plant Sci 85:631–639

Frame J, Charlton JFL, Laidlaw AS (1998) Temperate forage legumes. CAB International, New York

García-Latorre C, Rodrigo S, Santamaría O (2021) Endophytes as plant nutrient uptake-promoter in plants. In: Maheshwari DK, Dheeman S (eds) Endophytes: mineral nutrient management, Volume 3, Sustainable development and biodiversity 26, Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp 247-265

Hazelton P, Murphy B (2016) Interpreting soil test results. What do all the numbers mean?, 3rd edn. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton South

Hodge A (2004) The plastic plant: root responses to heterogeneous supplies of nutrients. New Phytol 162:9–24

Horinouchi H, Katsuyama N, Taguchi Y, Hyakumachi M (2008) Control of Fusarium crown and root rot of tomato in a soil system by combination of a plant growth-promoting fungus, Fusarium equiseti, and biodegradable pots. Crop Prot 27:859–864

Hotz C, Brown K (2004) Assessment of the risk of zinc deficiency in populations and options for its control. Food Nutr Bull 25:91–204

Hyakumachi M, Kubota M (2003) Fungi as plant growth promoter and disease suppressor. In: Dilip KA (ed) Fungal biotechnology in agricultural food and environmental applications. Basel, New York, pp 101–110

Ismail M, Hamayun M, Hussain A, Iqbal A, Khan SA, Lee IJ (2018) Endophytic fungus emopenAspergillus japonicusemclose mediates host plant growth under normal and heat stress conditions. Biomed Res Int Article 7696831:1–11

Ismail MA, Amin MA, Eid AM, Hassan SE-D, Mahgoub HAM, Lashin I, Abdelwahab AT, Azab E, Gobouri AA, Elkelish A, Fouda A (2021) Comparative study between exogenously applied plant growth hormones versus metabolites of microbial endophytes as plant growth-promoting for Phaseolus vulgaris L. Cells 10:1059

Kõljalg U, Nilsson HR, Schigel D, Tedersoo L, Larsson K-H, May TW, Taylor AFS, Jeppesen TS, Frøslev TG, Lindahl BD, Põldmaa K, Saar I, Suija A, Savchenko A, Yatsiuk I, Adojaan K, Ivanov F, Piirmann T, Pöhönen R, Zirk A, Abarenkov K (2020) The taxon hypothesis paradigm—on the unambiguous detection and communication of taxa. Microorganisms 8:1910

Lamhamdi M, El Galiou O, Bakrim A, Nóvoa-Muñoz JC, Arias-Estévez M, Aarab A, Lafont R (2013) Effect of lead stress on mineral content and growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea) seedlings. Saudi J Biol Sci 20:29–36

Leyte-Lugo M, Figueroa M, González MDC, Glenn AE, González-Andrade M, Mata R (2013) Metabolites from the entophytic fungus Sporormiella minimoides isolated from Hintonia latiflora. Phytochemistry 96:273–278

Lledó S, Rodrigo S, Poblaciones MJ, Santamaria O (2015) Biomass yield, mineral content, and nutritive value of Poa pratensis as affected by non-clavicipitaceous fungal endophytes. Mycol Prog 14:67 (online version)

Lledó S, Rodrigo S, Poblaciones MJ, Santamaria O (2016a) Biomass yield, nutritive value and accumulation of minerals in Trifolium subterraneum L. as affected by fungal endophytes. Plant Soil 405:197–210

Lledó S, Santamaría O, Rodrigo S, Poblaciones MJ (2016b) Endophytic mycobiota associated with Trifolium subterraneum growing under semiarid conditions. Ann Appl Biol 168:243–254

López-Sánchez A, Perea R, Dirzo R, Roig S (2016) Livestock vs. wild ungulate management in the conservation of Mediterranean dehesas: implications for oak regeneration. For Ecol Manag 362:99–106

Lyu S, Wei X, Chen J, Wang C, Wang X, Pan D (2017) Titanium as a beneficial element for crop production. Front Plant Sci 8:597

Maciá-Vicente JG, Rosso LC, Ciancio A, Jansson HB, Lopez-Llorca LV (2009) Colonisation of barley roots by endophytic Fusarium equiseti and Pochonia chlamydosporia: Effects on plant growth and disease. Ann Appl Biol 155:391–401

Mayerhofer MS, Kernaghan G, Harper KA (2013) The effects of fungal root endophytes on plant growth: a meta-analysis. Mycorrhiza 23:119–128

Moghaddam MSH, Safaie N, Soltani J, Hagh-Doust N (2021) Desert-adapted fungal endophytes induce salinity and drought stress resistance in model crops. Plant Physiol Biochem 160:225–238

Moreno G, Pulido FJ (2009) The functioning, management and persistence of dehesas. In: Rigueiro-Rodríguez A, McAdam J, Mosquera-Losada MR (eds) Agroforestry in Europe. Current status and future prospects. Springer, Netherlands, pp 127–160

Nanda S, Mohanty B, Joshi RK (2019) Endophyte-mediated host stress tolerance as a means for crop improvement. In: Sumita J (ed) Endophytes and secondary metabolites. Springer, Cham, pp 677–701

Newcombe G, Campbell J, Griffith D, Baynes M, Launchbaugh K, Pendleton R (2016) Revisiting the life cycle of dung fungi, including Sordariafimicola. PLoS One 11(2):e0147425

Newman CW, Newman RK (1992) Nutritional aspects of barley seed structure and composition. In: Shewry PR (ed) Barley: genetics, biochemistry, molecular biology and biotechnology. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 351–368

Olea L, San Miguel-Ayanz A (2006) The Spanish dehesa. A traditional Mediterranean silvopastoral system linking production and nature conservation. In: Lloveras J, González-Rodríguez A, Vázquez-Yáñez O, Piñeiro J, Santamaria O, Olea L, Poblaciones MJ (eds) 21st General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation. Sociedad Española para el Estudio de los Pastos, Madrid, pp 3–13

Perveen I, Raza MA, Iqbal T, Naz I, Sehar S, Ahmed S (2017) Isolation of anticancer and antimicrobial metabolites from Epicoccum nigrum; endophyte of Ferula sumbul. Microb Pathog 110:214–224

Pinto-Correia T, Ribeiro N, Sá-Sousa P (2011) Introducing the montado, the cork and holm oak agroforestry system of Southern Portugal. Agrofor Syst 82:99–104

Rasmussen S, Liu Q, Parsons AJ, Xu H, Sinclair B, Newman JA (2012) Grass-endophyte interactions: a note on the role of monosaccharide transport in the Neotyphodium lolii-Lolium perenne symbiosis. New Phytol 196:7–12

Rasmussen S, Parsons AJ, Bassett S, Christensen MJ, Hume DE, Johnson LJ, Johnson RD, Simpson WR, Stacke C, Voisey CR, Xue H, Newman JA (2007) High nitrogen supply and carbohydrate content reduce fungal endophyte and alkaloid concentration in Lolium perenne. New Phytol 173:787–797

Redman RS, Kim YO, Woodward CJDA, Greer C, Espino L, Doty SL, Rodriguez RJ (2011) Increased fitness of rice plants to abiotic stress via habitat adapted symbiosis: a strategy for mitigating impacts of climate change. PLoS One 6(7):e14823

Reid G, Dirou J (2004) How to interpret your soil test .Based on information from soil sense leaflet 4/92, Agdex 533. New South Wales Department of Primary industries, New South Wales

Rodrigo S, Santamaria O, García-White T, García-Latorre C (2018) Antagonism in vitro and in vivo between fungal endophytes and Fusarium moniliforme. In: Vázquez de Aldana B, Zabalgogeazcoa I (eds) 10th International Symposium on Fungal endophytes of Grasses. Institute of Natural Resources and Agrobiology, IRNASA-CSIC, Salamanca, pp 118

Rodrigo S, Santamaria O, Halecker S, Lledó S, Stadler M (2017) Antagonism between Byssochlamys spectabilis (anamorph Paecilomyces variotii) and plant pathogens: Involvement of the bioactive compounds produced by the endophyte. Ann Appl Biol 171:464–476

Rodriguez RJ, Henson J, Van Volkenburgh E, Hoy M, Wright L, Beckwith F, Kim YO, Redman RS (2008) Stress tolerance in plants via habitat-adapted symbiosis. ISME J 2:404–416

Rodriguez RJ, White JF, Arnold AE, Redman RS (2009) Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles: Tansley review. New Phytol 182:314–330

San Miguel A (1994) La Dehesa Española. Origen Topología Características y Gestión. Escuela Técnica Superior de Montes (Universidad Politécnica), Madrid

Santamaria O, Rodrigo S, Poblaciones MJ, Olea L (2014) Fertilizer application (P, K, S, Ca and Mg) on pasture in calcareous dehesas: effects on herbage yield, botanical composition and nutritive value. Plant Soil Environ 60:303–308

Santamaria O, Lledó S, Rodrigo S, Poblaciones MJ (2017) Effect of fungal endophytes on biomass yield, nutritive value and accumulation of minerals in Ornithopus compressus. Microb Ecol 74:841–852

Santamaria O, Rodrigo S, Lledó S, Poblaciones MJ (2018) Fungal endophytes associated with Ornithopus compressus growing under semiarid conditions. Plant Ecol Divers 11:581–595

Sauer AK, Hagmeyer S, Grabrucker AM (2016) Zinc deficiency. In: Erkekoglu P, Kocer-Gumusel B (eds) Nutritional deficiency. IntechOpen, London, pp 23–46

Schardl CL, Craven KD, Speakman S, Stromberg A, Lindstrom A, Yoshida R (2008) A novel test for host-symbiont codivergence indicates ancient origin of fungal endophytes in grasses. Syst Biol 57:483–498

Schnabel S, Dahlgren RA, Moreno-Marcos G (2013) Soil and water dynamics. In: Campos P, Huntsinger L, Oviedo Pro JL, Starrs PF, Diaz N, Standiford RB, Montero G (eds) Mediterranean oak woodland working landscapes: Dehesas of Spain and ranchlands of California. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 91–121

Silva MRO, Sena KX, Gusmão NB (2009) Secondary metabolites produced by endophytic fungus Paecilomyces variotii Bainier with antimicrobial activity against Enterococcus faecalis. In: Mendez-Vilas A (ed) Current research topics in applied microbiology and microbial biotechnology - II International Conference on Environmental, Industrial and Applied Microbiology. World Scientific, Seville, pp 519–520

Simón N, Montes F, Díaz-Pinés E, Benavides R, Roig S, Rubio A (2013) Spatial distribution of the soil organic carbon pool in a Holm oak dehesa in Spain. Plant Soil 366:537–549

Sosulski FW, Imafidon GI (1990) Amino acid composition and nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors for animal and plant foods. J Agric Food Chem 38:1351–1356

Soto-Barajas MC, Zabalgogeazcoa I, Gómez-Fuertes J, González-Blanco V, Vázquez-de-Aldana BR (2016) Epichloë endophytes affect the nutrient and fiber content of Lolium perenne regardless of plant genotype. Plant Soil 405:265–277

Tewari N, Vasudevan P, Guha BK (2005) Study on biosorption of Cr(VI) by Mucor hiemalis. Biochem Eng J 23:185–192

Waqas M, Khan AL, Hamayun M, Shahzad R, Kim YH, Choi KS, Lee IJ (2015) Endophytic infection alleviates biotic stress in sunflower through regulation of defence hormones, antioxidants and functional amino acids. Eur J Plant Pathol 141:803–824

Ważny R, Rozpądek P, Domka A, Jędrzejczyk RJ, Nosek M, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Lichtscheidl I, Kidd P, Turnau K (2021) The effect of endophytic fungi on growth and nickel accumulation in Noccaea hyperaccumulators. Sci. Total Environ 768:144666

Zabalgogeazcoa Í, Ciudad AG, Vázquez de Aldana BR, Criado BG (2006) Effects of the infection by the fungal endophyte Epichloë festucae in the growth and nutrient content of Festuca rubra. Eur J Agron 24:374–384

Zheng YK, Miao CP, Chen HH, Huang FF, Xia YM, Chen YW, Zhao LX (2017) Endophytic fungi harbored in Panax notoginseng: diversity and potential as biological control agents against host plant pathogens of root-rot disease. J Ginseng Res 41:353–360

Zhou XR, Dai L, Xu GF, Shen H (2021) A strain of Phoma species improves drought tolerance of Pinus tabulaeformis. Sci Rep 11:7637

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Teodoro García-White, Maria J. Poblaciones and Santiago Lledó for their invaluable help with the technical work.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research was funded by Project AGL2011-27454, granted by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain (the former Ministry of Science and Innovation) and by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rodrigo and Santamaria contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and/or data analysis were performed by the three authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by García-Latorre, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Section editor: Marc Stadler

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Latorre, C., Rodrigo, S. & Santamaria, O. Effect of fungal endophytes on plant growth and nutrient uptake in Trifolium subterraneum and Poa pratensis as affected by plant host specificity. Mycol Progress 20, 1217–1231 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-021-01732-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-021-01732-6