Abstract

This review presents the physical performance outcomes of randomised trials investigating exercise programmes that included balance exercise for older people with dementia. A systematic literature search through five computerised bibliographic databases until February 2009 was carried out. Of 1,038 potentially relevant published articles, only seven met the inclusion criteria and were extracted. Findings from the review for a total of 632 participants showed that almost all of the included studies addressed exercise or physical activities as the main intervention; however, only two of the studies focused on balance exercise. The effect size values varied from no effect (0.00) to a large effect (3.29) of the interventions for a range of physical performance outcome measures. Findings also suggest that it is feasible to conduct exercise programmes with older people with dementia. However, further studies with more specific exercise designed to improve balance performance in order to prevent falls are required for older people with dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia is a major health problem among older people. In 2001, it was estimated that 24.3 million people worldwide had dementia, and there were 4.6 million new cases of dementia every year [1]. This translates to one additional person being affected by dementia every 7 s [1]. As the world population ages and there is an increasing number of older people, it is expected that there will be a corresponding increase in the number of people with dementia.

Falls are another well-known public health issue in the older population. Nearly one in three people aged 65 years and over fall once or more each year [2, 3]. The incidence of falls is even greater in older people with dementia, with around 60% falling in each 6-month period [4] and 70–80% falling annually [5]. It has also been reported that this population experience falls at a rate two to three times that of the general older population [6, 7]. Falls often lead to functional limitation, loss of independence, loss of confidence, associated illness and mortality in this population [8–10]. People with dementia have been found to have more serious fall-related injuries [11].

One factor contributing to falls is reduced balance performance [12–14]. Consequently, balance exercise is considered to be an essential part of fall prevention programmes for older people. This has been confirmed by a number of systematic reviews of randomised controlled studies developed for fall prevention in the past two decades [15–18]. Greater levels of balance and gait impairment have been reported in people with dementia than would be expected with normal ageing [19, 20]. Decline in motor function and balance has also been identified in people with mild stages of Alzheimer's disease [21]. These findings may explain the increased incidence of falls in people with dementia. Moreover, decreased balance performance has been reported as a predictor of people with dementia requiring transition to permanent skilled nursing facilities [22].

To date, there is no published systematic review investigating the effects of exercise interventions specifically targeted at balance in people with dementia. There have been four previous systematic reviews of studies investigating the effects of exercise or physical activities for people with cognitive impairment or dementia [23–26]. However, only one [26] of these reviews clearly included only trials targeted at older people with dementia. The other studies included samples with mixed or unclear diagnoses of dementia and cognitively impaired older people. In addition, these reviews focused on the effects of exercise programmes and activities in general but did not separately consider the effectiveness of balance-specific exercise. Incorporating balance training appears to be an essential component of successful exercise interventions that reduce falls [17, 27]. This review seeks to address these gaps. The purpose of the present systematic review was to evaluate the available evidence on the effectiveness of balance exercise programmes (whether conducted alone or as part of broader physical intervention programmes) in improving balance performance and fall-related outcomes (such as number of falls and risk of falling) in older people with dementia.

Method

Search strategy

The literature search was conducted on the following computerised bibliographic databases: MEDLINE (1950 to January week 4, 2009), EMBASE (1988 to 2009 week 6), PsycINFO (1967 to February week 1, 2009), PEDro—the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (http://www.pedro.fhs.usyd.edu.au, accessed 11th February 2009)—and Ageline (accessed 11th February 2009) using keywords which are detailed in Table 1. Citation tracking for key articles (accessed 24th March 2009 via Google Scholar) and manually scanning the reference lists of potentially relevant trials were performed to identify additional published studies.

Criteria for inclusion

Inclusion criteria were established to filter relevant articles for the review. The studies were eligible for inclusion if they met all of the following criteria.

Participants

Studies were included if all the participants were older people (aged 65 years and over) with dementia. Studies that included people with younger onset of dementia (dementia diagnosed in people under the age of 65 years) were not included in the review. We included people with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, mixed Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia and other dementia with all levels of severity of dementia. Studies that reported they included “demented people” but that did not clearly identify that all included participants were diagnosed with dementia were excluded. Where a study included participants aged over 65 years with cognitive impairment, at least 80% of the sample needed to have a diagnosis of dementia for the study to be included in this review.

Intervention

To be included, interventions had to include exercise with at least one component focused on improving balance or reducing falls in older people with dementia. However, it was not deemed necessary for the balance exercise to be the major component of the intervention programme.

Outcome measures

We only included studies that reported at least one outcome measure relating to balance performance in the standing position or to risk of falling or fall-related measures such as injuries or hospitalizations related to falls. Studies that measured mobility performance that involved standing balance as a component in the measurement were also included. Additional outcome measures could also include functional ability, daily activity and other related measures such as quality of life, cognitive and behavioural measures.

Study design

Studies that used a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design comparing one or more interventions (incorporating exercise) and a control group were included. Only full articles published in English in a peer-reviewed journal were included in this review.

Criteria for exclusion

Studies that reported research conducted in which any of the participants were aged less than 65 years or studies in which less than 80% of the participants were older people with a diagnosis of any type of dementia were excluded from this review. Studies that focused on resistance, endurance or aerobic exercise or walking, which did not include a component of balance exercise were excluded. We also excluded studies using only indirect outcome measures of balance, for example, muscle strength or global functional performance. Articles that did not contain an intervention programme were excluded. Studies which scored a quality rating of less than 3 on the PEDro scale (see below) were also excluded from the review.

Selection of studies

One reviewer (PS) assessed the titles and abstracts obtained from the search, and any studies clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria were discarded. Two reviewers (KH and PS) then scrutinised full paper copies of the potentially relevant studies according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria described above. All studies that appeared to meet the selection criteria were included. Disagreement in determining suitability of papers for inclusion was resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

In the present review, five out of seven selected studies had previously been rated by PEDro's criteria and indexed on PEDro—the physiotherapy evidence database (http://www.pedro.org.au/). These scores have been adopted in this review. The quality of the two studies not rated on the PEDro database was independently assessed by the two reviewers (KH and PS) using the PEDro scale. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion to achieve a consensus score.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the included studies using a customised data extraction tool based on a standardised data extraction template for Cochrane Reviews [28]. The elements were adapted to the aims of this review. The following information were extracted: population, type of dementia, severity of dementia, inclusion/exclusion criteria, setting, intervention (especially information about balance exercise), outcome measures, results, study design and limitations of the study.

Data analysis

Effect sizes (ES) were calculated from individual studies to examine the effectiveness of each intervention by quantifying the difference between experimental and control groups using the standardised mean difference method [29, 30]. Each individual study ES was calculated where the mean, the standard deviation (SD) and number of participants in each group were available from the published reports. In studies where the intervention programmes combined exercise training with another intervention (i.e. occupational therapy, physical education or cognitive behavioural therapies, support group or other medical treatments), the ES was calculated based on the results from the exercise intervention only if available. The (timed) get up and go test outcomes were converted into positive values to calculate the ES. This reflects the fact that a decrease in time taken to perform this task represents an improvement in mobility performance, in contrast to the other included measures, where an increase in score reflected improved performance.

The individual ES calculation was conducted using a Web-based ES calculator (available at: http://www.cemcentre.org/renderpage.asp?linkid=30325017) from which the bias-corrected ES estimates were reported. The bias correction used the Hedges and Olkin factor [29]. The ES results were interpreted based on Cohen's convention for size of effect on standardised difference between two groups [31] by which ESs ranging from 0.2 to <0.5 are defined as “small effect”, from 0.5 to <0.8 as “medium effect” and ≥0.8 as “large effect”. Where insufficient data were provided, the data were analysed descriptively only. A meta-analysis was not performed because of the heterogeneity of characteristics of the interventions and outcome measures.

Results

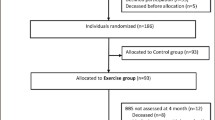

Search strategy yields

Figure 1 summarises the literature search. The search strategy yielded 1,038 studies. Examination resulted in the exclusion of 918 studies as they did not include either people with a diagnosis of dementia or did not incorporate exercise interventions. One hundred and twenty abstracts were screened, and a further 87 studies were excluded because they also did not meet all the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 33 studies were considered as potentially relevant for this review. However, a further 26 studies were excluded after full papers were reviewed. Reasons for exclusion of these studies were that fewer than 80% of included participants were diagnosed as having dementia [32–34] or included demented people but did not clearly explain the term “demented” [35, 36] or they included people aged under 65 years [37]; the studies had a physical intervention which did not include any balance training component [38–42]; the studies did not assess balance performance or fall-related outcome measures or did not report the results of balance or fall-related outcomes [37, 41–53] and one potentially relevant study [54] used a non-RCT design and low methodological quality (PEDro score of lower than three) [55, 56]. This left a total of seven RCTs for review. Table 2 shows the data extracted from each study as well as the quality rating scores (PEDro score).

Participants

The seven included studies generated a sample size of 632 participants of whom 321 and 311 were in the intervention and control groups, respectively. As shown in Table 2, the number of participants in each study varied from 16 to 274; two studies [57, 58] included more than 100 participants. Only one study [58] included a mixed sample of people with and without a diagnosis of dementia (approximately 90% of included participants [246 out of 274 participants] having a diagnosis of dementia). Sample size calculations were reported in only two studies [58, 59].

Five of the seven studies reported both the mean age and SD [57, 60–63]. The combined mean age ± SD of these studies was 79.7 ± 7.3. Two further studies [58, 59] reported age ranges of 66–98 and 70–98 years, respectively.

Gender proportions were reported in all studies. In one study [62], there were only female participants. In the other six studies, the included participants were primarily female. Overall, the proportion of female participants was a mean of approximately 76%.

Three studies [57, 60, 61] included only residents of institutions (hospital, nursing home or other residential care facilities). Another study [58] included participants from both residential facilities (approximately 78%) and community facilities (approximately 22%). Participants were community living in the other three studies [59, 62, 63]. Consequently, approximately 66% (418 participants) of the participants were institutional residents.

Interventions

As illustrated in Table 2, four [57, 59, 61, 62] of the seven studies included exercise programmes or physical activities as the main intervention in their protocols. Three studies [58, 60, 63] provided a multi-intervention programme in which exercise was one of four interventions [58] and one of three interventions [60, 63] in the protocols. The study of Christofoletti et al. [60] compared three groups: (1) an interdisciplinary group (exercise by a physiotherapist [PT] and group activities by an occupational therapist), (2) an exercise group conducted by PT and (3) a control group. The present review focuses on information reported from the exercise alone intervention group in the study. Neither of the other two studies [58, 63] used a full factorial design, which would have required comparisons of all possible interventions and combinations across all factors or interventions to enable identification of the exercise intervention component outcomes in isolation. Generally, the programmes involved combined exercise which included flexibility, strengthening, walking and balance components. The exercise interventions were described as a “physical therapy” programme in three studies [58–60] and included balance and gait with mobility or with functional re-training [58, 59] and strength and balance exercise with cognitive stimulation [60]. Another study [63] conducted Taiji (tai chi) exercises consisting of strength and balance training. Of the seven studies, only two specifically stated that the exercise programmes were specially aimed to improve balance [60, 63].

Frequency of the intervention programmes ranged from twice a week [57] to twice a day [58]. The intervention programmes were performed from a minimum of 30 min to a maximum of 60 min per session. The duration of the interventions ranged from 2 weeks to 12 months (approximately 6 months on average).

Group exercises were performed in three [57, 61, 63] of the studies, but only two studies reported the number of participants per group, which were two to five [57] and four [61]. Three studies [58–60] consisted of individual exercises, in which one delivered a home-based exercise programme [58]. Another study [62] did not specify whether the exercises were individual or group.

The individual exercise programmes in all three studies [58–60] were supervised by a physiotherapist. However, the group exercise interventions in the other three studies [57, 61, 63] were supervised by an occupational therapist [57], an exercise scientist [61] and Taiji (tai chi) instructors [63].

Specific details of the balance exercise varied in the reports. None of the included studies reported the duration of the balance training component as a proportion of the whole of the exercise intervention programme. Details about the balance training component was reported in only three studies [57–59] and consisted of balance re-education in sitting or standing position [59] and one- or two-leg balance exercise (standing on toes with and without support [58] or on firm or foam rubber surface [57]). The balance training components in the other four studies [60–63] were reported as a part of the kinesiotherapeutic exercises (combination of balance, strengthening and cognitive stimulation exercises) [60], coordination and balance exercises [61], lower extremity exercises [62] and a Taiji (tai chi) training programme [63]. Exercise programmes involving games or activities with equipment (e.g. cones, hoop, foam rubber sheets, Bobath balls, Swiss ball, elastic ribbons and proprioceptive stimulation plates) were reported in three studies [57, 60, 62]. Only one study [58] provided for a progression of the balance exercises through four levels (1 to 4) that corresponded to progressively decreasing support and increasing manoeuvrability during standing balance activities.

Outcome measures

There was a wide variety of outcomes assessed and reported in the studies reviewed. Details of type of measurements and the time lines of assessments can be seen in Table 2. The outcome measures included measurements of balance performance (the Berg balance scale, the Tinetti scale and one-leg balance test); mobility and gait (timed get up and go test, Southampton mobility assessment); walking tests (speed and distance); functional fitness assessments (strength, flexibility, agility and endurance); activity of daily living (ADL); falls and related consequences such as fall-related attendance at the emergency department or hospital admission or mortality and psychological or cognitive tests as well as reports of feasibility and compliance. Functional balance and mobility were the most frequent outcome measures undertaken in the studies, with the Berg balance scale being the most commonly used measure of balance performance.

Effectiveness of intervention programmes

The effectiveness of the physical activity interventions is summarised in Table 2. Significant improvements were seen in the following variables: walking speed [57], gait score (from the modified performance-oriented mobility assessment [POMA]) [58], mobility score (from Southampton mobility assessment) [59], ADL scores [61, 62], Berg balance scale [60], POMA (Tinetti scale) [61], duration of exercise or endurance [61], time chair stand [61], lower extremity strength [62], upper extremity strength [61], flexibility [61, 62] and agility [61, 62]. No significant improvements were reported in the fall-related outcome measures. A number of non-physical outcome measures were also reported including the mini mental state examination (MMSE) score [62, 63], self-esteem scale [63], verbal fluency test [60] and clock drawing test [60].

Of the seven studies, only four provided the mean and SD of physical performance variables of the treatment and control groups and the number of participants of each group for the results reported. Physical performance outcomes were classified under four categories: mobility (the Southampton mobility and timed get up and go test), walking (2-min walking test and 6-m walking test), balance (Berg balance scale and single leg stance test) and ADL (Katz index of ADLs). The bias-corrected ES values and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the ES are presented in Fig. 2. These ES values ranged from 0.00 to 3.29. Analysis of the ES values according to the sub-grouping of physical outcome measures was identified.

-

For the mobility outcome measures, the ES ranged from 0.00 (95% CI, −0.36, 0.36) to 1.85 (95% CI, 0.97, 2.73), which is classified as no effect to a large ES;

-

For the walking outcome measures, the ES ranged from 0.23 (95% CI, −0.13, 0.60; small effect) to 0.55 (95% CI, 0.10, 1.01; medium ES);

-

For the balance outcome measures, the range of ES was from 0.07 (95% CI, −0.62, 0.76; no effect) to 3.29 (95% CI, 2.17, 4.41; large effect) and

-

For the ADL measures, which were assessed at two time points (6 and 12 months) in the study by Rolland et al. [57], ES values of 0.07 (95% CI, −0.29, 0.43) and 0.26 (95% CI, −0.11, 0.64; small effect) were obtained, respectively.

Three studies reported attendance or participation information. Almost 42% of participants in the Rolland et al. trial [57] attended fewer than one third of the exercise sessions, and the overall mean number of sessions attended by participants who completed the study was only 33.2 ± 25.5% of the 88 sessions. Another study [61] reported a 98.9% rate of attendance. Seventy-five percent of participants in the study by Burgener et al. [63] attended all Taiji (tai chi) sessions with 90% of the sample attending at least two of the three sessions weekly.

Quality of studies

Five of the seven studies were rated on the PEDro database, with scores ranging from four to eight from the total score of ten. The remaining two studies [61, 63] were rated by the current reviewers (KH and PS) using PEDro criteria as 6/10. Five (71.4%) of the studies had a quality rating greater than five.

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review of the literature located only seven published randomised controlled studies assessing the effectiveness of balance training as a component of an exercise intervention, on the balance performance of older people with dementia. The heterogeneity of the characteristics of the participants, the intervention programmes and the outcome measures of the included studies limits the conclusions able to be derived.

Only four studies provided data suitable for calculating an ES. The ES calculation results vary from no effect to large effect (ES values ranged from 0.00 to 3.29) of the exercise intervention on physical performance outcomes for people with dementia. Factors possibly contributing to the limited ES in two of the studies could include an insufficient rate of attendance (33.2 ± 25.5% of classes were attended on average) [57]; and the fact that in the study by Burgener et al. [63], the comparison between the intervention and control groups was made at the 20th week of a 40-week intervention programme. Variation in the effectiveness of the programme between a control group and an intervention group may be expected to be greater at the 40th week than halfway through the programme.

The effectiveness of exercise interventions appeared to be greater on balance and mobility outcomes than other physical performance outcome measures, with five out of nine balance and mobility outcomes being rated as having a medium or large effect. Of note, the study by Christofoletti et al. [60] showed a large effect (ES ± SE = 3.29 ± 0.57) on the Berg balance scale. The fact that the exercise programme concentrated on strength and balance stimulation may explain the magnitude of the effectiveness of the programme on the functional balance measurement in this study. The individual approach of the physiotherapist could be another key element in the success of the programme. However, the marked variability in ESs and lack of homogeneity in samples, interventions and outcome measures means that no firm conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of these programmes.

This review did not demonstrate the effectiveness of the exercise interventions in any fall outcome measures (e.g. falls, fallers and time to first fall). Only one study [58] did measure fall outcomes and did not achieve significant outcomes on these measures. Factors that may have contributed to this lack of effect include that the programme was conducted in people with moderately severe dementia (intervention group mean MMSE = 14, control group mean MMSE = 12) with high falls risk (who had fallen and presented to an emergency department). It is possible that the potential to respond to the interventions may be more limited [24] or slower to achieve, in people with greater cognitive impairment or frailty. The study [58] involved multi-factorial interventions that included a 3-month duration exercise programme. The nature of exercise interventions for people with dementia may also need some modification compared to programmes that have been shown to be successful in reducing falls in non-cognitively impaired older people. Modifications such as increasing the duration and frequency of exercise sessions and changing the types of exercises to accommodate the specific balance impairments and tasks that can be performed safely by people with dementia may improve implementation feasibility in this clinical group, and possibly also impact on fall outcomes.

The results of our review need to be considered in the context of several other reviews of exercise interventions in people with cognitive impairment or dementia. A previous review [23] has supported the proposition that exercise programmes can improve physical fitness, cognitive and behavioural outcomes in people with cognitive impairment and dementia. However, the evidence for effectiveness of physical activity programmes in this population is still limited, as is concluded by our review and two previous systematic reviews [24, 26]. Only one [24] of these reviews evaluated fall outcomes of exercise programmes in this clinical group. There has been an increase in studies evaluating exercise programmes for people with dementia in recent years, although most of these evaluated cognitive and behaviour-related outcomes [42, 48, 52, 64].

Measurements of balance and mobility performance were the most frequent outcome measures undertaken in the studies, and some balance measures appeared to be responsive to the interventions. However, almost all of the studies measured balance performance in terms of functional ability, mostly using functional rating tools such as the Berg balance scale and the POMA (Tinetti scale). Most of the functional balance tests provide only a general picture of balance performance. As balance is complex and multi-dimensional [65–67], a more comprehensive balance assessment battery of well-validated, sensitive measures should be considered to identify the specific elements that contribute to the improvement or decline in performance. This may then provide a clearer picture of the effectiveness of balance-related outcomes and also identify aspects of the exercise interventions that warrant greater focus [65–67].

The older people with dementia included in the studies varied in the type of dementia as well as the severity of dementia. There was also additional variation in functional and mobility performance. Only two of the studies [57, 61] specifically included only participants with Alzheimer's disease, while the other studies included participants with diagnoses of dementia of any type. Differences in types and severity of dementia could result in different characteristics of impairment and cognitive or physical limitation within the sample [68] and ability to respond to an exercise intervention programme. There is value in future studies considering relatively homogenous samples (e.g. incorporating only participants with a single diagnosis of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, or vascular dementia).

Almost all of the studies had methodologic limitations, and only two studies [57, 58] were rated as being of high methodological quality (PEDro score ≥7). Only one of these studies [57] targeted specifically a single type of dementia (Alzheimer's disease). Sample size was another research limitation. Studies either had a small sample size [61–63] or the calculation of sample size was not reported [57, 60–63]. Future studies with a more rigorous research design and with adequate sample size would give better evidence of the effects of exercise in people with dementia.

Nearly two thirds of the participants included in this review were residents of institutions. Residents of institutions generally have a more severe level of dementia and other co-morbidities than people with dementia living in the community, and there are differences relating to supervision and staffing in institutional settings that suggest that effectiveness of exercise programmes for people living in the community and those living in residential care may need to be considered separately. There is a clear need for further studies in this area, particularly for older people with dementia living at home. There is also a need to evaluate these exercise interventions for people with less severe dementia, when they are more likely to be able to actively and safely participate in exercise programmes, particularly those that aim to improve balance performance.

To date, there is no report of a well-conducted RCT utilising a balance exercise programme designed to improve balance performance and to reduce risk of falls, which was specifically targeted to people with mild to moderate dementia who were living in the community. These are important research gaps to be addressed, given the growing prevalence of dementia, and the increasing number of people with dementia who remains supported in the community setting to later stages of disease progression [5, 24].

Although the value of the exercise interventions is being increasingly acknowledged, full benefits may only be realised when a high level of compliance is achieved. In this review, attendance and participation rates were reported in only three studies [57, 61, 63]. One possible factor contributing to lower participation may be the length of the programme. One study that had a 12-month duration of exercise [57] reported a low rate of attendance, whereas the 3-month study [61] reported substantially higher attendance rates. Another study [63] conducted a Taiji (tai chi) programme over 5 months had a high rate of attendance. In this study, follow-up phone calls were made to remind participants when they had missed an intervention class. However, this is not a sufficient database from which to form any definite conclusion as to the length of the programme needed to maximise compliance and therefore effectiveness. Other factors can be relevant to participation rates, especially the perceived benefits to be derived from an intervention programme, frequency of the programme, ongoing support, variety in the programme and engagement of carers. It should be noted that carers are a critical element in the life and in the direction of care of older people with dementia, and factors in implementation of exercise programmes that accommodate carer needs (e.g. time and location of classes, availability of transport, and costs) need to be considered.

Although most participants were recruited from residential care, the results of this review suggest that exercise programmes for older people with dementia are feasible. Fall prevention programmes have obvious benefits to both the individual and to society as a whole [69, 70], and exercise programmes incorporating balance training are an established effective approach to reducing falls in older people without dementia.

Study limitations

Only seven studies that met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in this systematic review were identified. Unfortunately, the elements needed for conclusions to be satisfactorily drawn were not always present, resulting in low-quality ratings for several of the studies. Future RCTs should follow Consort statement guidelines [71] to maximise design rigour. Not all of the included studies reported the nature of the exercise programmes, so information about which programme included balance training and the duration of the programme were not always available. To assess the effectiveness of training programmes of this nature, this information should be included in published reports.

Conclusion

This systematic review identified only seven studies that met the three following inclusion criteria: (1) participants were older people (aged 65 years and over) with dementia, (2) the intervention included balance exercises and (3) one or more balance-related outcomes were measured. The results from ES calculations vary from no effect (0.00) to large effect (3.29) of exercise interventions implemented in people with dementia for physical performance assessed over a range of measures. For measures of balance performance, ES ranged from 0.07 to 3.29, so no conclusive statement about effectiveness can be made. Findings from the systematic review support the feasibility of conducting exercise interventions in this clinical group.

The systematic review suggests the need for further research to evaluate the effectiveness of balance training exercise to reduce falls risk in people with dementia. Future studies should target samples with a single type of dementia (e.g. Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia) as the effects on balance performance and responsiveness to interventions may vary between differing diagnoses. Given the projected growth in the prevalence of dementia and the increased focus on maintaining community living as long as possible, future studies should also target community-living samples.

Abbreviations

- SLS:

-

Single leg stance

- EC:

-

Eyes closed

- EO:

-

Eyes open

- BBS:

-

Berg balance scale

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

References

Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M (2005) Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 366:2112–2117

Gill T, Taylor AW, Pengelly A (2005) A population-based survey of factors relating to the prevalence of falls in older people. Gerontology 51:340

Morris M, Osborne D, Hill K, Kendig H, Laudgren-Lindquist B, Browning C, Reid J (2004) Predisposing factors for occasional and multiple falls in older Australians who live at home. Aust J Physiother 50:153–159

Eriksson S, Gustafson Y, Lundin-Olsson L (2008) Risk factors for falls in people with and without a diagnose of dementia living in residential care facilities: a prospective study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 46:293–306

Shaw FE (2003) Falls in older people with dementia. Geriatr Aging 6:37–40

Horikawa E, Matsui T, Arai H, Seki T, Iwasaki K, Sasaki H (2005) Risk of falls in Alzheimer's disease: a prospective study. Intern Med 44:717–721

Jensen J, Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y (2002) Falls among frail older people in residential care. Scand J Public Health 30:54–61

Hill K, Kerse N, Lentini F, Gilsenan B, Osborne D, Browning C, Harrison J, Andrews G (2002) Falls: a comparison of trends in community, hospital and mortality data in oder Australians. Aging Clin Exp Res 14:18–27

Scaf-Klomp W, Sanderman R, Ormel J, Kempen GIJM (2003) Depression in older people after fall-related injuries: a prospective study. Age Ageing 32:88–94

Zijlstra GAR, van Haastregt JCM, van Eijk JTM, van Rossum E, Stalenhoef PA, Kempen GIJM (2007) Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling, and associated avoidance of activity in the general population of community-living older people. Age Ageing 36:304–309

van Dijk PTM, Meulengerg OGRM, van de Sande HJ, Habbema DF (1993) Falls in dementia patients. Gerontologist 33:200–204

Lord SR, Sambrook PN, Gilbert C, Kelly PJ, Nguyen T, Webster IW, Eisman JA (1994) Postural stability, falls and fractures in the elderly: results from the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology study. Med J Aust 160(684–685):688–691

Lord S, Lloyd DG, Li SK (1996) Sensori-motor function, gait patterns and falls in community-dwelling women. Age Ageing 25:292–299

Russell MA, Hill KD, Blackberry I, Day LL, Dharmage SC (2006) Falls risk and functional decline in older fallers discharged directly from emergency departments. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61A:1090

Gardner MM, Robertson MC, Campbell AJ (2000) Exercise in preventing falls and fall related injuries in older people: a review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 34:7–17

Chang JT, Morton SC, Rubenstein LZ, Mojica WA, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Roth EA, Shekelle PG (2004) Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 328:680–686

Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Close JC (2008) Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:2234–2243

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Lamb SE, Gates S, Cumming RG and Rowe BH (2009) Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Visser H (1983) Gait and balance in senile dementia of Alzheimer's type. Age Ageing 12:296–301

Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P, d'Athis P, Dubost V, Mourey F (2006) Impact of cognitive task on the posture of elderly subjects with Alzheimer's disease compared to healthy elderly subjects. Mov Disord 21:236–241

Pettersson AF, Engardt M, Wahlund L-O (2002) Activity level and balance in subjects with mild Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 13:213

Kenny AM, Bellantonio S, Fortinsky RH, Dauser D, Kleppinger A, Robison J, Gruman C, Trella P, Walsh SJ (2008) Factors associated with skilled nursing facilities transfers in dementia-specific assisted living. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 22:255–260

Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ (2004) The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85:1694–1704

Hauer K, Becker C, Lindemann U, Beyer N (2006) Effectiveness of physical training on motor performance and fall prevention in cognitively impaired older persons: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 85:847–857

Christofoletti G, Oliani MM, Gobbi S, Stella F (2007) Effects of motor intervention in elderly patients with dementia: an analysis of randomized controlled trials. Top Geriatric Rehabil 23:149–154

Forbes DA, Forbes SC, Markle-Reid M, Morgan DG, Taylor BJ and Wood J (2008) Physical activity programs for persons with dementia (intervention review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Province MA, Hadley EC, Hornbrook MC, Lipsitz LA, Miller JP, Mulrow CD, Ory MG, Sattin RW, Tinetti ME, Wolf SL (1995) The effedts of exercise on falls in elderly patients. A preplanned meta-analysis of the FICSIT trails. Frailty and injuries: coorperative studies of intervention techniques. JAMA 273:1341–1347

Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. Data extraction templates for Cochrane reviews. Updated 7 March 2007

Hedges LV, Olkin I (1985) Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic, Orlando

Deeks JJ and Higgins JPT (2007) Statistical algorithms in Review Manager 5. The Cochrane collaboration. Accessed 1 Sep 2008

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Jensen J, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y, Lundin-Olsson L (2003) Fall and injury prevention in residential care; effects in residents with higher and lower levels of cognition. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:627–635

Lazowski DA, Ecclestone NA, Myers AM, Paterson DH, Tudor-Locke C, Fitzgerald C, Jones G, Shima N, Cunningham DA (1999) A randomized outcome evaluation of group exercise programs in long-term care institutions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54:M621–M628

Rosendahl E, Lindelof N, Littbrand H, Yifter-Lindgren E, Lundin-Olsson L, Haglin L, Gustafson Y, Nyberg L (2006) High-intensity functional exercise program and protein enriched energy supplement for older persons dependent in activities of daily living: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother 52:105–113

Netz Y, Axelrad S, Argov E (2007) Group physical activity for demented older adults-feasibility and effectiveness. Clin Rehabil 21:977

Toulotte C, Fabre C, Dangremont B, Lensel G, Thevenon A (2003) Effects of physical training on the physical capacity of frail, demented patients with a history of falling: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 32:67–73

Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, Kukull WA, LaCroix AZ, McCormick W, Larson EB (2003) Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:2015–2022

Palleschi L, Vetta F, De Gennaro E, Idone G, Sottosanti G, Gianni W, Marigliano V (1996) Effect of aerobic training on the cognitive performance of elderly patients with senile dementia of alzheimer type. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 22:47–50

Hageman PA, Thomas VS (2002) Gait performance in dementia: the effects of a 6-week resistance training program in an adult day-care setting. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17:329–334

Kuiack SL, Campbell WW, Evans WJ (2003) A structured resistive training program improves muscle strength and power in elderly persons with dementia. Act, Adapt, Aging 28:35–47

Thomas VS, Hageman PA (2003) Can neuromuscular strength and function in people with dementia be rehabilitated using resistance-exercise training? Results from a preliminary intervention study. J Gerontol 58A:746

Stevens J, Killeen M (2006) A randomised controlled trial testing the impact of exercise on cognitive symptoms and disability of residents with dementia. Contemp Nurse 21:32–40

Friedman R, Tappen RM (1991) The effect of planned walking on communication in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 39:650–654

Tappen RM (1994) The effect of skill training on functional abilities of nursing home residents with dementia. Res Nurs Health 17:159–165

Teri L, McCurry SM, Buchner DM, LaCroix LRG, AZ KWA, Barlow WE, Larson EB (1998) Exercise and activity level in Alzheimer's disease: a potential treatment focus. J Rehabil Res Dev 35:411

Arkin SM (1999) Elder rehab: a student-supervised exercise program for Alzheimer's patients. The Gerontologist 39:729

Cott CA, Dawson P, Sidani S, Wells D (2002) The effects of a walking/talking program on communication, ambulation, and functional status in residents with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 16:81–87

Van de Winckel A, Feys H, De Weerdt W (2004) Cognitive and behavioural effects of music-based exercises in patients with dementia. Clin Rehabil 18:253–260

Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Damush TM, Perkins AJ, Fultz BA, Hui SL, Counsell SR, Hendrie HC (2006) Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer's disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 295:2148–2157

Littbrand H, Rosendahl E, Lindelof N, Lundin-Olsson L, Gustafson Y, Nyberg L (2006) A high-intensity functional weight-bearing exercise program for older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilities: evaluation of the applicability with focus on cognitive function. Phys Ther 86:489–498

Forbes D (2007) An exercise programme led to a slower decline in activities of daily living in nursing home patients with Alzheimer's disease. Evid Based Nurs 10:89

Williams CL, Tappen RM (2007) Effect of exercise on mood in nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimer's Dis Other Dement 22:389–397

Steinberg M, Leoutsakos J-MS, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos C (2009) Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24:680–685

Arkin SM (2003) Student-led exercise sessions yield significant fitness gains for Alzheimer's patients. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 18:159–170

Buettner LL (2002) Focus on caregiving. Falls prevention in dementia populations. Provider 28:41–43

Pomeroy VM (1993) The effect of physiotherapy input on mobility skills of elderly people with severe dementing illness. Clin Rehabil 7:163–170

Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A, Reynish E, Thomas D, Andrieu S, Riviere D, Vellas B (2007) Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease: a 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:158–165

Shaw FE, Bond J, Richardson DA, Dawson P, Steen IN, McKeith IG, Kenny RA (2003) Multifactorial intervention after a fall in older people with cognitive impairment and dementia presenting to the accident and emergency department: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 326:73

Pomeroy VM, Warren CM, Honeycombe C, Briggs RSJ, Wilkinson DG, Pickering RM, Steiner A (1999) Mobility and dementia: is physiotherapy treatment during respite care effective? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14:389–397

Christofoletti G, Oliani MM, Gobbi S, Stella F, Bucken Gobbi LT, Renato Canineu P (2008) A controlled clinical trial on the effects of motor intervention on balance and cognition in institutionalized elderly patients with dementia. Clin Rehabil 22:618–626

Santana-Sosa E, Barriopedro MI, Lopez-Majares LM, Perez M, Lucia A (2008) Exercise training is beneficial for Alzheimer's patients. Int J Sports Med 29:845–850

Kwak YS, Um SY, Son TG, Kim DJ (2008) Effect of regular exercise on senile dementia patients. Int J Sports Med 29:471–474

Burgener SC, Yang Y, Gilbert R, Marsh-Yant S (2008) The effects of a multimodal intervention on outcomes of persons with early-stage dementia. Am J Alzheimer's Dis Other Dement 23:382–394

Williams CL, Tappen RM (2008) Exercise training for depressed older adults with Alzheimer's disease. Aging Ment Health 12:72–80

Shumway-Cook A, Woollacoot MH (2007) Postural control. In: Shumway-Cook A, Woollacoot MH (eds) Motor control: translating research into clinical practice, 3rd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 157–257

Bernhardt J, Hill K (2005) We only treat what it occurs to us to assess: the importance of knowledge-based assessment. In: Refshauge K, Ada L, Ellis E (eds) Science-based rehabilitation: theories into practice. Butterworth Heinemann, Edinburgh, pp 15–48

Duncan PW, Shumway-Cook A, Tinetti ME, Whipple RH, Wolf S, Woollacott M (1993) Is there one simple measure for balance? PT Magazine, pp 74–80.

Mitnitski AB, Graham JE, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K (1999) The rate of decline in function in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54:M65–M69

Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cummings RG, Rowe BH (2008) Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR (2006) Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 35(Suppl 2):ii37–ii41

Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T, CONSORT Group (2001) The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 134:663–694

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Suttanon, P., Hill, K., Said, C. et al. Can balance exercise programmes improve balance and related physical performance measures in people with dementia? A systematic review. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 7, 13–25 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11556-010-0055-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11556-010-0055-8