Abstract

This system-level ethnographic study of a strength-based approach to transforming a national invention education program makes visible how program leadership drew on research and their own expertise to shift who and how they served. With data analysis grounded in program reports, documentation, and internal and published research, the program’s developmental trajectory is (re)constructed and (re)presented with contextual details provided by program leadership to bring forward how facets of a strength-based approach informed the overtime transformation. Working in conjunction with program leadership to identify common design elements across new program offerings, this study presents this program’s principles for designing for instruction and considerations for curricular integration of invention education into K-14 educational institutions. Furthermore, how these principles align with a strength-based approach are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

My parents are Lebanese and lived in Lebanon until they graduated college during the [Lebanese] civil war and then they immigrated to find jobs… my grandma, for example, lost her husband when she had kids… she went from being a math teacher to having to run this business and put her kids through college. And I’d consider that fairly entrepreneurial, which to me are the same skills as inventing and resiliency….

-Mira Moufarrej, addressing the assets she drew upon to become an inventor for the documentary movie Pathways to Invention, Stanford University, 2021 Lemelson-MIT Program (LMIT) “Cure It” Graduate Student Prize Winner for inventing a prenatal liquid biopsy test.

We all had something great to put into this [invention experience and project] and it meant that wherever somebody fell a little short [in particular knowledge or skills], another person was ready [to step in] and [then] another person….

-Vinny Morales, addressing his greatest lesson learned as a student-invention team member in Invention and Inclusive Innovation (i3) at Chaffey Community College, Rancho Cucamonga, California, Summer 2021.Footnote 1

Accounts of the lived experiences of people like student inventors Mira and Vinny are central to ethnographers’ examination of culture within social groups. Ethnographers’ documentation of words people use, contextual cues for the meanings being conveyed, actions taken, and objects used or produced become part of purposefully constructed research archives. Ethnographers draw on records in this ethnographic space to produce data (Green et al., 2017). Triangulation of the data allows for warranted claims about the patterned ways of thinking, knowing, being and doing, among those recognized as members of a social group. This study, conducted from an ethnographic perspective, draws on archived records associated with educational initiatives offered by a national program in the United States focused on invention known as the Lemelson-MIT Program (LMIT). Artifacts within the archive include inscriptions of life of the LMIT staff as well as educators and students with whom LMIT interacted. Activities of this group during the study period focused on identifying and coming to understand problems faced by people in local communities and the development of technological solutions that could be patented under the rules set forth by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

The program studied is administered within the School of Engineering at a university in the United States that is highly prone to patentingFootnote 2. The program is one of several national invention education (IvE) program providers in the U.S. whose work contributes to diversifying those who invent, protect their ideas, and solve problems that matter while exposing diverse students to STEM careers (Invention Education Research Group, 2019). Our first reading of the contents of the research archive revealed that the program’s initiatives had shifted significantly in recent years. How LMIT conceptualized the development of an inventor and the guiding principles informing the design of new initiatives were not transparent. Statements like, “all kids can learn to invent” made us wonder if the principles guiding the LMIT Program were consistent with the strength-based approach emerging from positive psychology and used in many K12 schools to promote health, well-being, and academic achievement in education or in other fields such as psychotherapy and social work. Thus, we chose to undertake a research study, grounded in the principles and practices of ethnography, to (re)construct who did what, with whom and under what conditions, to bring about the shifts that had transpired. We also wanted to determine if the purpose of the shifts related to new norms and expectations that were strength-based.

Research Questions (RQs)

The overarching objective of this study is to determine ways the guiding principles of the program align with a strength-based approach (or not). Research questions that we unfold systematically to address this overarching objective are:

-

RQ1:

How did the LMIT program shift its program offerings and who was served between 2016 and 2022?

-

RQ2:

What influenced shifts in the program’s initiatives? What were the phases of inquiry, key decisions, and activity along LMIT’s axis of their developing program?

-

RQ3:

What common approaches and principles of design are reflected in the initiatives? How do the common approaches and principles reflect a “strength-based” approach, if any?

-

RQ4:

What potential programmatic shifts or revisions to principles of practice are realized through the reflexive actions of the Executive Director acting as a researcher to examine the program through a strength-based lens?

Positionality of the Authors

The ways that we, authors, study social, cultural, and economic forms of capital (Ade-ojo, 2021) and literacies in relation to invention and IvE are guided by our personal and professional experiences and a logic-of-inquiry grounded in interactional ethnography (Skukauskaitė & Green, 2023). The first author has been the Executive Director of the Lemelson-MIT program, the ‘site’ of this study, since 2016 and led the program’s transformation over the study’s time period. She was first introduced to a ‘strength-finding’ approach in 2002 while working as a director of an educational technology program affiliated with community colleges.

The second author is an independent researcher-ethnographer, Latina, and former Academy Professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Through guiding diverse cadet-learners in a student-centered instructional design for undergraduate General Chemistry, she witnessed first-hand how these learning environments provide the space for students to access their strengths. Since 2020, she has contributed to research in half of LMIT’s new initiatives. However, she was not privy to the larger transformation taking place at LMIT. Through her ongoing ethnographic research with LMIT and the first author, the second author observed that these new initiatives seemed to be guided by a strength-based approach. This study afforded both authors an opportunity to step back from what they thought they knew, to re-examine the ways of thinking, knowing, being and doing within LMIT over the study’s time period.

Conceptual Framework, Methodology and Methods

Our conceptual framework is informed by socio-cultural theories and an anthropological and discourse-based approach to ethnography (Green et al., 2020; Skukauskiate & Green, 2023). A number of traditions are developing because of ongoing ethnographic work being done as a community of inquiry. Like duo-ethnography, we bring multiple actors together who have different background knowledge. For this study, we draw on the internal and external ethnographer roles and relationship (Green et al., 2017; Green & Bridges, 2018) as a support structure for the dialogic conversations at the point of analysis. This collaboration supported the undertaking of a reflexive and abductive process central to an ethnographic logic-of-inquiry. The process is guided by principles of conduct derived from anthropological perspectives with an emphasis on discourse described by Heath and Street (2008) as follows:

-

Stepping back from ethnocentrism;

-

Learning from and with participants;

-

Making connections to construct new (emic) ways of knowing; and,

-

(Re)presenting what is known by local actors and what the ethnographers learn from the analysis at different levels of analytic scale.

Through this process, the external ethnographer supports the internal ethnographer to collaboratively make visible the emic meanings for interpretation by outsider-readers. This ethnographic perspective guides the multiple layers of analysis needed to systematically document and analyze LMIT’s complex social system and the different layers of decision-making and actions that were being taken across time. In this way, the logic-of-inquiry, methodology and methods are made explicit in this study by making visible abductive phases of inquiry: a deliberate analytic process of resolving a research question which then informs the next research question and analyses.

Corpus of Data

The initial research archive, constructed in accordance with an ethnographic perspective, was supplemented as the study progressed with additional artifacts required to thoroughly examine each sequential research question (Kalainoff & Chian, 2023). Table 1 summarizes the artifacts in the final archive, how and when these were collected, and which RQs or section in this paper each type supports.

Initial Entry into the Research Archive

This section describes two actions, guided by an ethnographic perspective, that were taken upon entering the research archive. Our first action, aligning with our overarching research question, was to read the archive ethnographically by examining the artifacts in relation to ‘invention’, ‘innovation’, and a ‘strength-based lens’ which included consulting additional research literature. This first action led to identifying a ‘rich point’ (Agar, 2006) in the archive as a starting place for the process of building an empirically guided logic or sequence of research questions that collectively address the overarching research question.

Reading the Archive Ethnographically and Literature Informing our Inquiry

Studies published by LMIT staff defined “invention, and more specifically technological invention, [as] the process of devising and producing by independent investigation, experimentation, and mental activity something that is useful and that was not previously known or existing.”Footnote 3 A 2004 report of the Committee for Study of Invention, a committee sponsored by the National Science Foundation and LMIT, offered insights into the work of inventors and ways the work differs from other approaches to problem-based learning. The report notes that “routine problem-solving and invention represent opposite ends of a design continuum, with increasing specification and predictability associated with routine problem solving and increasing ‘boundary transgression’ and uncertainty associated with invention” (Magee et al., 2004).

The 2004 study portrayed invention as a precursor to innovation, or the bringing forth of something new and novel to intended audiences. Invention, combined with entrepreneurial activity, leads to innovation. Our review of the research literature had shown that studies examining innovation and the conditions needed to foster innovation in particular geographic regions, also called place-based innovation, have used a strength-based lens to generate understandings of factors that support and constrain innovation (Myende & Hialele, 2018; Myende, 2015; Emery & Flora, 2006). Emery and Flora (2006), for example, documented the interconnectedness of seven factors that allow for the ‘spiraling up’ of communities in ways that improve conditions for residents. The seven types of capital are: (1) natural (physical context), (2) cultural (way people “know” the world and how they act with it), (3) human (skill and capabilities of people), (4) social (connections among people), (5) political (access to power), (6) financial, and (7) built environment (physical infrastructure).

A more recent study in the archive conducted by a LMIT staff member, reflected Emery and Flora’s notion that cultural knowledge and practices and social relations are a type of capital present within communities, and demonstrated that social and cultural community wealth are a resource for invention and innovation. Specifically, the LMIT staff member’s study found that high school students’ lived experiences aided their identification of a local problem and design of an invention prototype that was new and novel, useful, unique, and non-obvious (Saenz, 2022). This study posited that learner-inventors bring differential strengths to these processes. Students who grow up in communities of color, for example, bring unique types of cultural capital and Funds of Knowledge (Gonzalez et al., 2020) as assets to their learning and development. The paper, citing Yosso’s (2005) Community Cultural Wealth theory, described these assets as navigational, linguistic, aspirational, social, resistant, and familial. Other studies in the research archive gave accounts of these and other types of capital that students activated during their work as inventors.

The vast majority of documents in the archive portrayed LMIT’s role as one in which educators and students were the primary actors with whom staff engaged. The documents did not explicitly reference “strength-based teaching”. The authors, however, developed an understanding of strength-based instruction through findings in the research literature that linked strength-based teaching to promoting well-being including positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (Seligman, 2011). The five domains were shown to impact mental health, well-being, and academic achievement (Waters et al., 2019). Galloway et al. (2020) offered examples of ways teachers enacted this approach, rooted in positive psychology, in school contexts:

A uniform finding in the study was that all five teachers implemented: (1) processes for identifying children’s strengths that involved the recognition and acknowledgement of children’s preferences, abilities and passions (Linley & Harrington, 2006), (2) processes for applying children’s strengths when teachers encourage children to “be aware of what they can use those strengths to achieve, accomplish, and overcome” (Brownlee et al., 2012, p.8), and (3) processes for developing children’s strengths enabling students to improve known competencies (Biswas-Deiner et al., 2011). (Galloway et al., 2020, p. 40)

These perspectives served as our initial guide in how to characterize the term ‘strength-based’ in K-14 educational contexts.

As researchers studying the LMIT program, the extent to which social, cultural, and other forms of capital were deliberately engaged through the program’s efforts constituted an unknown. We also did not fully understand how the approach to working with learners, educators, and communities reflected a strength-based approach. However, the publications in the archive caused us to wonder if fully engaging all forms of capital, including social and cultural capital, may assist with work to bridge significant differences across the U.S. among those whose inventions are formally recognized through the award of a patent. The percentage of patents awarded, for example, vary greatly according to gender, race/ethnicity, income, and geographic location. The differences within and at the intersections of these categories (Burrage et al., 2022) suggests that greater diversity in who invents could bring forward new perspectives and new ideas for solving the many global and local problems that plague society. Through this initial inquiry, we recognized a potential for using strength-based framing to better understand how LMIT has developed current program offerings, how it can expand the use of this framing to improve its offerings, and how it can promote strength-based teaching practices through these offerings.

Identifying a ‘Rich Point’ to Initiate the Logic-of-Inquiry for this Study

During our examination of LMIT’s 2022 report we identified a rich point within the document. A rich point is an unexpected surprise that initiates a question to anchor an abductive phase of inquiry. This history and rich point inscribed within the report spoke to the organization’s shifts as follows:

[LMIT]… has been celebrating inventors and working to inspire young people to pursue creative and inventive lives since 1994. Cash prizes were awarded annually for nearly three decades (each of 26 years) to prolific adults and collegiate inventors who inspire educators and youth. LMIT expanded its efforts in 2004 to include direct engagement with high school educators and youth in the problem-finding and prototype-development processes common to inventors through our national grant initiative, InvenTeams. Invention education (IvE) efforts with educators and students across the United States have continued to grow since that time. Program offerings now support opportunities for learning across all grades K–12 and the first two years of college. Approximately 732 educators and 2,662 students benefitted directly from LMIT offerings in 2022. The IvE efforts, and the growing numbers of educators and students served, are part of a comprehensive strategy for realizing LMIT’s and The Lemelson Foundation’s commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). (Lemelson-MIT, 2022, p.1)

This report segment caused us to wonder about the relationship between shifts in program offerings and LMIT’s claim that it had a comprehensive strategy for realizing its commitment to DEI, and whether this strategy was grounded in a strength-based approach. This rich point seeded the first research question by orienting us to ‘where’ to initiate our analytic route through the archived records: shifts in program offerings and who was served.

Layers of Analyses: Addressing the Research Questions

This section unfolds four research questions that collectively address the relationship between LMIT’s guiding principles and a strength-based approach.

-

RQ1: How did the LMIT program shift its program offerings and who was served between 2016 and 2022?

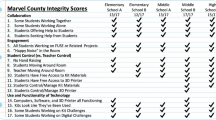

Table 2 was compiled from three layers of data constructed from archived records of LMIT annual reports from 2016 to 2022. These funder reports were selected because they coincided with the tenure of the current Executive Director and first author whose hiring as a new leader in 2016 represented one of many shifts in this time-period. The reports are comprehensive and contain LMIT staff’s inscriptions of who did what, with whom, and over time. The documents offer evidence of the programmatic activities and outcomes that were consequential from the perspectives of the LMIT staff and the program’s benefactor, and significant enough to be recorded as a part of the grant reporting process. The three major sections of the table address: (1) what LMIT offerings/initiatives were available, (2) who was served by each initiative in each year, and (3) what LMIT resources were provided as part of each initiative in 2022 or in the last year of each initiative.

Table 2 lists program offerings by year in which they were initiated. The first five initiatives, the three prize programs for student and prolific inventors, high school InvenTeams and the middle school junior varsity (JV) InvenTeams, began before 2016, the initial year of our range of interest. Who was served is shown by year for each offering. No entry means that the program did not exist in that year. Resources provided in 2022 or in the last year of the offering are also listed. The resources shown include cash prizes for awardees and various types of instructional programs, curricular resources, and professional development opportunities for other groups served.

Table 2 shows that the program offered collegiate student prizes between 1994 and 2021. Invention and Inclusive Innovation (i3), a program initiated in 2021, was piloted at four two-year colleges that same year. Mira, a 2021 graduate level Student Prize winner, and Vinny, a community college student-invention team member, cited in the opening of this paper are two of many student-inventors whose stories are captured as artifacts in the archive for the program – our site of study. Mira and Vinny represented the last and first students, respectively, to participate in two different invention-oriented initiatives offered by LMIT. Both stories contained inscriptions of their personal experiences as members of a team while working as inventors. Their stories offered glimpses into students’ conceptions of the “strengths” activated through engagement in invention activities. The students’ accounts, when cross referenced with program documents in the archive, also validate our findings reflected in Table 2 which showed that pivotal shifts were made in who the invention program served and their ways of serving educators and students.

Patterns emerging from the analysis of the data from the archived records showed shifts that LMIT made in its program offerings over the seven-year period. Examination of these patterns suggests the following shifts between 2016 and 2022:

-

a.

Shift in programming: Until 2018, five programs had been a mainstay for the LMIT program: three prolific and collegiate prize programs for 24 years and two IvE programs serving grades 6–12 across a 14-year period. Between 2018 and 2021, the prize programs ended and five invention programs for K-14 were initiated. The collegiate prize program’s 26-year history and accomplishments were documented in a final report, a research publication, and a documentary film titled Pathways to Invention. A new initiative at the community college level launched in 2021 restored LMIT’s work with adults of all ages. In 2022, a new initiative for MIT students that began as a research internship retained some LMIT efforts at the four-year collegiate level.

-

b.

Shift in who is served: LMIT had recognized prolific and collegiate student inventors prior to 2021. By 2022, LMIT had completely shifted towards leveraging what they had learned in 18 years of its high school InvenTeams initiative to growing student inventors through supporting IvE learning opportunities for K-14 educators and students.

-

c.

Shift in resources provided: Between 2019 and 2021, as the prize programs ended, resources shifted towards providing curricular material and professional development opportunities for faculty to develop IvE programs at their educational institutions as well as directly engaging with students in IvE.

This analysis that traces programmatic shifts demonstrates that LMIT’s developmental transition was characterized by a greater allocation of resources towards serving faculty and students with invention education and professional development to build IvE capacity and programs across grades K-14. The next research question examines why this occurred.

-

RQ2: What informed or influenced shifts in the program’s initiatives? What were the phases of inquiry, key decisions, and activity along LMIT’s axis of their developing program?

To explore ‘why’ shifts shown in Table 2 occurred, we drew on additional records that were relevant to our question. We were aware that LMIT’s strategies had been informed by numerous internal research studies conducted in the previous six years. Nevertheless, the conduct of this study required us to step back from what we thought we knew about ways the prior research influenced changes that LMIT made to its offerings so that we could take a new look from the perspective of a professional stranger (Agar, 1996). Therefore, we added LMIT research and case studies to the research archive to create summary Tables 3 and 4, respectively, to address RQ2.

Table 3 shows 20 internally produced and 5 externally produced publications and reports that informed LMIT’s programming. Of these 25 documents, 23 are found on the LMIT website and two were externally funded and not public. These documents are listed by year and in terms of the authors, research site, and report or publication topic and findings.

Table 4 shows case studies found on the LMIT website by year, authors, research site, report or publication topic and pertinent findings. Of these 18 case studies between 2017 and 2021, 15 are InvenTeam or JVInvenTeam success stories to inspire educators and students. Details provided by the informant show that in 2016 LMIT used its public website as a ‘living’ archive to document and make public the external research that they were drawing on and the internal research that they were producing to share what was being learned. Therefore, the research publications and case studies serve as a record of what knowledge and topics had captured the attention of staff engaged in the research. Given the time necessary to publish research findings and the uncertainties of knowing if findings from research were translated into new practices, the informant was interviewed about where and how these findings from research contributed to LMIT’s decision-making and developmental trajectory.

As part of this layer of analysis, the informant and external ethnographer used the timeline of initiatives in Table 2, research and reports in Table 3, and case studies in Table 4 to jointly and iteratively construct the major phases of work identified by the informant in co-reflexive dialogues. We also identified key activities within each phase of work that were referenced in these reports and studies as having informed the emerging learnings and challenges. The significant activities where LMIT was engaged before and after LMITs decision to change its programming in January of 2018 are depicted in Fig. 1. This axis of development (AoD) (Kalainoff & Chian, 2023; Kalainoff & Clark, 2017) represents outcomes and the final step of the analytic process undertaken to address RQ2.

In the context of this study, the generalized AoD is an axis of a developing IvE support program, specifically LMIT, developing over time from left to right. How this program was developing, namely through the interactions between LMIT program staff and the other actors in this setting, which includes IvE initiatives, sites, and research, are represented by two threads rotating around each other over time that produce the axis at the center. The diagram demonstrates that LMIT staff and the initiatives at particular sites co-develop over time. This interactional dimension of the AoD gives rise to successive phases of development represented by each 180-degree rotation of the two interacting actors in the system. In a developing program, these are abductive phases of inquiry where initial known and unknown elements of the context are resolved over the course of each phase. The process of resolving the object of inquiry in each phase also seeds new unknowns to inform the next phase of inquiry. Because the lessons, outcomes, and new unknowns in each phase of inquiry are consequential for the next phase (i.e., an abductive process), the specific characteristics of each phase cannot be predetermined.

The axis of this developing IvE support program is shown in two main phases that were determined by the way LMIT staff oriented their invention education efforts: Phase 1, characterized as ‘IvE as an exemplar and seeding change’, represents LMIT’s focus through January 2018 with the decision to eliminate the prize programs. Phase 2, characterized as ‘IvE for all’, depicts the program’s expansion into K-14 programming during the school day. Phase 2 shows further sub-phases or shifts in program staff’s orientation from initiating program transformation (Phase 2a) to developing and piloting initiatives (Phase 2b), and communicating and leveraging change efforts (Phase 2c).

Within the details of each phase and subphase of activity, and their knowns, unknowns, and outcomes, we can begin to see an argument developing for ‘why’ a shift was undertaken starting in January 2018. Namely, in Phase 1, LMIT staff’s 2017 annual report (Lemelson-MIT, 2017) to its funders raised concerns about the small number of students reached and cost per student which presented a challenge for achieving broader impact. The notation of a high ratio of money spent to students served in Phase 1 signaled a weakness perceived by the staff and one that they may have sought to address in the changes in subsequent years. The program’s research publications also contained evidence of a growing awareness of the differences in who invents and earns a U.S. patent (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, geography, and income). At that time, eligibility for LMIT programs was not limited to those who are underrepresented among those who invent and obtain patents. Figure 1 shows that, in Phase 1 as LMIT shifted from Prize programs to an emphasis on developing inventors through IvE, a new unknown emerged: ‘How should the program shift to better address DEI challenges?’ This unknown seeded the questions for the next phase of inquiry in LMIT’s developmental process. The shift in object of inquiry required that LMIT orient the program to new questions and resources.

-

RQ3: What common approaches and principles of design are reflected in the initiatives? How do the common approaches and principles reflect a “strength-based” approach (if at all)?

This research question pertaining to the principles of design reflected in the approaches that were common across the LMIT program initiatives was informed by Estabrooks and Couch (2018). This study described activities embedded within the design of LMIT’s initiatives as:

…being drawn from the literature describing ways inventors approach non-routine problem solving. The authors identified four types of actions or phases of activity, including: (1) identifying and defining a problem; (2) conducting inquiries and identifying, listening, and learning about what matters to end users; (3) designing solutions; and (4) building and testing physical prototypes (Aulet, 2013; Middendorf, 1981; Shavinina & Seeratan, 2003; Wagner, 2012). (Estabrooks & Couch, 2018, p. 105)

The study noted that the phases of activity are typically carried out in an iterative and recursive manner (Frigotto, 2018). In other words, the inevitable instances in which the inventors’ actions do not work leads to a revisiting of the phases of activity, thereby accounting for a nonsequential process.

Common approaches to ways the activities noted above are enacted across each grade span and the underlying principles guiding the approach were not visible in the publication. Further insights into common approaches across initiatives were identified by analyzing the reports to funders, publications, case studies, and by interviewing the informant and analyzing her accounts of the practices of LMIT. Descriptions of LMIT’s approach, the principles of practice underlying the approach articulated by the informant, and research and experiences on which the informant based the principles, appear in Table 5.

We also compared the common approaches and principles for the LMIT program to the literature surrounding strength-based approaches to determine if the elements of LMIT’s initiatives could be considered strength-based. The last column of Table 5 shows that we identified 16 of the 20 principles as being aligned with a strength-based approach. The degree of alignment was surprising given that the program does not appear to have consulted the strength-based literature as part of its curriculum design efforts.

The positionality of the first author as both researcher and the Executive Director, and findings for RQ1 and RQ2 which demonstrated a relationship between LMIT’s programmatic shifts and its research and case studies, caused us to wonder how the findings from RQ3 might impact future programmatic shifts. New insights generated by the present research study could result in a reframing of the principles of practice underlying the IvE curricular or instructional designs. This possibility led to a reframing of RQ4.

-

RQ4: What potential programmatic shifts or revisions to principles of practice are realized through the reflexive actions of the Executive Director as researcher in the examination of the program through a strength-based lens?

In the last phase of the study the external ethnographer interviewed the informant to uncover her insider perspective on how the findings generated by the study were impacting her thinking and the actions she might take in the future as an Executive Director. Interview questions probed her initial conceptions of ways the existing programmatic approach and underlying principles of practice reflected a strength-based approach, and then asked her about ideas for future actions or changes that would enhance the strength-based approach. A semantic analysis of the transcript and an opportunity for the informant to supplement the interview data with notes pertaining to what she was learning from the literature enabled the researchers to produce data shown in Table 6.

In Table 6, the informant identified seven areas where further programmatic shifts could deepen LMIT’s approach to recognizing and leveraging strengths. The existing work recognized the value of diverse teams, including cultural capital and community wealth. There were several practices, however, that could be better aligned with strength-based practices. For example, program participants are asked to map assets in the local ecosystem to support invention but the use of appreciative inquiry to explore the full range of cultural capital and community wealth may not be stated explicitly in curricular materials. Incorporating the steps needed to uncover cultural capital and community wealth as an explicit part of the ecosystem mapping process in LMIT initiatives would, from the perspective of the informant, get others to adopt a strength-based lens as they work to discover cultural capital and community wealth in their own local ecosystem.

Findings and Implications

This research study demonstrates a systems approach informing the trajectory of LMIT’s invention education program offerings that are strength-based. This section discusses two key findings and their implications.

Strength-based Alignment with the Literature

This study systematically uncovered an alignment between the IvE approaches and principles guiding educators affiliated with LMIT, the strength-based practices related to health and well-being enacted by other educators, and strength-based approaches taken in other fields such as psychotherapy and social work (McCashen, 2005). The alignment included practices surrounding the recognition and activation of personal assets that can be classified as social and cultural capital or community wealth (Yosso, 2005). Research publications in the fields of psychotherapy, social work, and positive psychology in educational contexts indicate that the strength-based approach fosters mental health, well-being, and personal growth and resiliency (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) while also having community benefits (Foot & Hopkins, 2010). Parallel benefits were claimed by invention educators for their work and documented in research publications and case studies shown in Tables 3 and 4.

LMIT’s strength-based approach also aligned with the literature pertaining to business management (Rath, 2007). In StrengthsFinder, a guide for reflecting on personal career paths, Rath argues that individual strength is derived from natural talents that are built on through the addition of knowledge, skills, and regular practice. Rath eschews the notion that “you can be anybody”, arguing that success begins with natural talent that can then be amplified through other actions to develop. His perspective aligns with perspectives shared by LMIT Student Prize winner Matthew Rooda who argued that parents examining their children’s report card often focus on the low grade. Instead, Rooda urges parents and educators to focus on strengths revealed by the ‘A grades’:

They’ll never be great at the C [grade], but they’re gonna be excellent at the A [grade]. How can we continue to invest in that [A grade] and inspire our students and our children to focus on the things that we think they might be great at someday? (Rooda, M., interview transcript, July, 2022)

LMIT IvE activities focused on student engagement in the community, emphasis on collaboration, and processes for identifying resources in the local ecosystem, aligns with community change efforts that used appreciative inquiry and strength-based approaches documented by other researchers (Emery & Flora, 2006; Myende & Hialele, 2018; Myende, 2015). LMIT’s efforts to bring about change in schools by expanding IvE to other educators to build pathways to invention, or continuous learning opportunities across all grades constitute a community and/or institutional change effort (White & Murray, 2015; Roffey, 2012). In an interview with the informant, she noted that:

The approach we use with teachers and students requires both to work deeply in the community and to bring about their individual efforts in collaboration with other community stakeholders. This is key to invention projects, the support needed by the school for broader take-up on an ongoing basis across all grade levels, and for the benefit of the inventions to be realized through adoption and wider use associated with commercialization and manufacturing.

Contributions to Research Process Methodology

This study unfolds the systematic and principle-guided reflexive turn in which institutional leaders as insider-ethnographers collaborate with ethnographers who come alongside to analyze and (re)present a complex developmental process. The reflexive stance made visible through this telling case reveals the institution’s AoD across time and events. In doing so, we show how the institution’s internal research informs the iterative, recursive, and abductive process of developing theories for learning and development.

We also show how the theories emerging from research guide decision-making and change within the program. The research processes enabled LMIT to communicate what was being learned through publications. Our analysis of the connections between research and the actions of this social group made visible the dynamic systems approach in which internal-external ethnographer dialogues fuel continuous improvement along an AoD. Exploring the fit between principles guiding LMIT’s initiatives and those portrayed as a strength-based approach make the abductive component of interactional ethnography visible. In this stage of the analytic process, researchers begin to examine a new theory that may have explanatory power for new understandings emerging from the systematic analysis of LMIT’s AoD.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that processes and practices employed by LMIT and collaborators to foster the development of inventors are aligned with descriptors of strength-based approaches in the fields of psychotherapy, psychology (related to health and well-being of students), social work, and business (or workforce development). The benefits of the strength-based approach documented through research in these other fields resembles the benefits of invention education described in LMIT publications. Additional studies to compare and contrast what counts as strength-based and to re-theorize what is being accomplished by those taking up IvE from a strength-based perspective may produce new insights that can further the LMIT Program’s axis of development in future years.

Notes

Student produced video, ‘The Spirit of Invention’: https://youtu.be/PTzAcExU_R8.

References

Ade-ojo, P. G. (2021). Bourdieu’s capitals and the socio-cultural perspective of literacy frameworks: A ready-made vessel for decolonising the curriculum. Academia Letters, 173. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL173

Agar, M. (1996). The professional stranger. Academic.

Agar, M. (2006). An ethnography by any other name…. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4). http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Alford, Z., & White, M. A. (2015). Positive school psychology. In M. A. White & A. S. Murray (Eds.), Evidence-based approaches in positive education: Implementing a strategic framework for well-being in schools (pp. 93–109). Springer.

Aulet, B. (2013). Disciplined entrepreneurship: 24 steps to a successful startup. Wiley.

Bell, A., Chetty, R., Jaravel, X., Petkova, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2018). Who becomes an inventor in America? The importance of exposure to innovation. https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/patents_paper.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & Minhas, G. (2011). A dynamic approach to psychological strength development and intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology,6(2), 106–118.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). Elsevier.

Brownlee, K., Rawana, E. P., & MacArthur, J. (2012). Implementation of a strengths-based approach to teaching in an elementary school. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 8(1), 1–12.

Buckingham, M., & Clifton, D. O. (2001). Now, discover your strengths. Simon and Schuster.

Burrage, A., Ciemiecki, J., Couch, S., & Ganguli, I. (2022). Inclusive pathways to invention: Racial and ethnic diversity among collegiate student inventors in a national prize competition. Technology & Innovation,22(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.21300/22.3.2022.8

Cima, M., & Couch, S. (2021). Comments submitted to USPTO Re: National strategy for expanding American innovation. Retrieved from https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2021-02/Cima%26Couch_USPTO_20621_final.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Committee on STEM Education. (2022). Convergence education: A guide to transdisciplinary STEM learning and teaching. National Science and Technology Council. Retrieved on April 15, 2023 from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Convergence_Public-Report_Final.pdf

Cook, L. D., Gerson, J., & Kuan, J. (2022). Closing the the innovation gap in pink and black. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policy and the Economy, 1(1), 43–66. Accessed 17 Feb 2024

Couch, S. R. (2012). An ethnographic study of a developing virtual organization in education. (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara). Available from proquest dissertations and theses database.

Couch, S., & Cima, M. (2019). Testimony for USPTO success act hearing: Study of underrepresented classes chasing engineering and science. Lemelson-MIT. Retrieved from https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2020-04/SUCCESS%20ACT%20TESTIMONY_6.1.19.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Couch, S. R., & Estabrooks, L. B. (2020). Policy initiatives needed to foster female inventors’ contributions to U.S. economic growth. https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2020-08/LMIT-FemaleInventorsResearchWhitePaper-07.20.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Couch, S., Estabrooks, L. B., & Skukauskaitė, A. (2018). Addressing the gender gap among patent holders through invention education policies. Technology & Innovation,19(4), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.21300/19.4.2018.735

Couch, S., Skukauskaitė, A., & Estabrooks, L. B. (2019a). Invention education and the developing nature of high school students’ construction of an inventor identity. Technology & Innovation,20(3), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.21300/20.3.2019.285

Couch, S. R., Skukauskaitė, A., & Green, J. L. (2019b). Invention education: Preparing the next generation of innovators. Technology & Innovation,20(3), 161–163. https://doi.org/10.21300/20.3.2019.161

Couch, S., Kalainoff, M., Estabrooks, L., Zhang, H., Perry, T., Ayele, A., Marvelle, A., Cameron, A., & Haney, C. (2020a). Biogen-MIT Biotech in Action Program evaluation report. Lemelson-MIT.

Couch, S., Skukauskaitė, A., & Estabrooks, L. B. (2020b). Telling cases that inform an understanding of factors impacting the development of inventors from diverse backgrounds. Technology & Innovation,21(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.21300/21.2.2020.133

Couch, S., Estabrooks, L., Kalainoff, M., & Sullivan, M. (2022). Final report: Invention and inclusive innovation (i3) initiative: 2021, summer and fall implementations. Lemelson-MIT Program.

Eccles, J. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 75–146). Freeman.

Emery, M., & Flora, C. (2006). Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community Development,37(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330609490152

Estabrooks, L. B., & Couch, S. (2018). Failure as an active agent in the development of creative and inventive mindsets. Thinking Skills and Creativity,30, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.015

Estabrooks, L., Zhang, H., Perry, A., Chung, A., & Couch, S. (2020). Where’s the computer science in invention? An exploration of computer science in high school invention projects. Lemelson-MIT. https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2021-04/CS_in_InvEd_Dec_2019.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Ewell, E., Haglid, H., Truszkowski, E., Walicki, C., De Meulder, P., Stephens, P., Labowsky, H. L. (2022). Invention as a complement to high school chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 99(5). https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/150026. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Committee for Study of Invention. (2004). Invention: Enhancing inventiveness for quality of life, competitiveness, and sustainability. Lemelson-MIT and National Science Foundation. Retrieved from https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2020-04/Invention%20Assembly%20Full%20Report.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Foot, J., & Hopkins, T. (2010). A glass half full: How an asset approach can improve community health and wellbeing. Improvement and Development Agency.

Frigotto, M. L. (2018). Understanding novelty in organizations: A research path across agency and consequences. Springer.

Gale, J. (2022). Inventing the baby saver: An activity systems analysis of applied engineering at the high school level. Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research,12(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.7771/2157-9288.1312

Galloway, R., Reynolds, B., & Williamson, J. (2020). Strengths-based teaching and learning approaches for children: Perceptions and practices. Journal of Pedagogical Research,4(1), 31–45.

Gonzalez, E., Fernandez, F., & Wilson, M. (2020). An asset-based approach to advancing Latina students in STEM: Increasing resilience, participation, and success. Routledge.

Green, J., & Bridges, S. (2018). Interactional ethnography. In F. Fischer, C. E. Hmelo-Silver, S. R. Goldman, & P. Reimann (Eds.), International handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 475–488). Routledge.

Green, J., Chian, M., Stewart, E., & Couch, S. (2017). What is an ethnographic archive an archive of? Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia,39, 112–131. https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2017.39.11466

Green, J. L., Baker, W. D., Chian, M. M., Vanderhoof, C., Hooper, L., Kelly, G. J., Skukauskaitė, A., & Kalainoff, M. Z. (2020). Studying the over-time construction of knowledge in educational settings: A microethnographic discourse analysis approach. Review of Research in Education,44(1), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X20903121

Hammond, W. (2010). Principles of strength-based practice. Resiliency initiatives. Retrieved from https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/PrinciplesOfStrength-BasedPractice.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2023

Heath, S. B., & Street, B. V. (2008). On ethnography: Approaches to language and literacy research. Teachers College Press.

Invention Education Research Group. (2019). Researching invention education. https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2020-04/ResearchingInventEdu-WhitePaper-2.21.2020.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Kalainoff, M. Z., & Chian, M. M. (2023). Unfolding principled actions for ethnographic archiving as an axis of development. In A. Skukauskaitė & J. L. Green (Eds.), Interactional ethnography: Designing and conducting discourse-based ethnographic research (pp. 187–212). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003215479-12

Kalainoff, M. Z., & Clark, M. G. (2017). Developing a logic-of-inquiry-for-action through a developmental framework for making epistemic cognition visible. In M. Clark & C. Gruber, (Eds.) Leader Development Deconstructed (pp. 209–248). Annals of Theoretical Psychology, vol 15. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64740-1_10

Kalainoff, M. Z., Couch, S. R., & Cima, M. (2022). Lemelson-MIT Student Prize Retrospective. Lemelson-MIT. Retrieved from https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2022-12/StudentPrizeWinners_Impacts.pdf and https://lemelson.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2022-12/InventorDevelopmentalPathways.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Kim, D., Cho, E., Couch, S., & Barnett, M. (2019). Culturally relevant science: Incorporating visualizations and home culture in an invention-oriented middle school science curriculum. Technology & Innovation,20(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.21300/20.3.2019.251

Kim, D., Kim, S., & Barnett, M. (2021). That makes sense now! Bicultural middle school students’ learning in a culturally relevant science classroom. International Journal of Multicultural Education,23(2), 145–172.

Lemelson-MIT. (2017). Lemelson-MIT Program Long-Term Strategic Plan. Lemelson-MIT.

Lemelson-MIT. (2022). Final project update and expense report. Grant number: 21-01968. Lemelson-MIT.

Linley, P. A., & Harrington, S. (2006). Playing to your strengths. Psychologist,19(2), 86–89.

Magee, C. L., Sheppard, S., & Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J. (2004). How should education change to improve our culture of inventiveness? In Committee for the Study of Invention (Ed.), Invention: Enhancing inventiveness for quality of life, competitiveness, and sustainability (pp. 52–62). Lemelson-MIT Program and the National Science Foundation.

McCashen, W. (2005). The strengths approach. St Luke’s Innovative Resources.

Middendorf, W. H. (1981). What every engineer should know about inventing. CRC Press.

Miller, B., Metz, D., Schmid, J., Rudin, P., & Blumenthal, M. S. (2021). Measuring the value of invention: The impact of Lemelson-MIT Prize winners’ inventions. Rand.

Myende, P. E. (2015). Tapping into the asset-based approach to improve academic performance in rural schools. Journal of Human Ecology,50(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2015.11906857

Myende, P. E., & Hialele, D. (2018). Framing sustainable rural learning ecologies: A case for strength-based approaches. Africa Education Review (online). https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2016.1224598

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

Rashid, T. (2009). Positive interventions in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology,65, 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20588

Rath, T. (2007). StrengthsFinder 2.0. Gallup.

Rock, D. & Grant, H. (2016). Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review, 4(4), 2–5. Accessed 17 Feb 2024

Roffey, S. (2012). Pupil wellbeing—teacher wellbeing: Two sides of the same coin? Educational and Child Psychology,29(4), 8.

Saenz, C. (2022). The narratives of Latina Students who have participated in invention education. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Central Florida). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020. 1279. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/1279. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

Saenz, C., & Skukauskiate, A. (2022). Engaging Latina students in the invention ecosystem. Technology and Innovation, 22, 303–313. Retrieved on March 29, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.21300/22.3.2022.4

Saenz, C., Skukauskaitė, A., & Sullivan. M. (2024). Becoming an inventor: A young Latina's narrative. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1293237. Accessed 10 Mar 2024

Seitz, H. (2023). Authentic assessment: A strengths-based approach to making thinking, learning, and development visible. YC Young Children, 78(1), 6–11.

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychological Association, 55(1), 5.

Shapiro, C., Meyers, A., & Toner, C. (n.d.). Strength-based family-focused practice: A clinical guide from family justice. Family Justice Organization.

Shavinina, L. V., & Seeratan, K. L. (2003). On the nature of individual innovation. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.), The international handbook on innovation (pp. 31–43). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044198-6/50004-8

Skukauskaitė, A., & Green, J. L. (Eds.). (2023). Interactional ethnography: Designing and conducting discourse-based ethnographic research. Taylor and Francis.

Wagner, T. (2012). Creating innovators: The making of young people who will change the world. Scribner.

Waters, L. E., Loton, D., & Jach, H. K. (2019). Does strength-based parenting predict academic achievement? The mediating effects of perseverance and engagement. Journal of Happiness Studies,20(4), 1121–1140.

White, M. A., & Murray, A. S. (2015). Building a positive institution. In M. A. White & A. S. Murray, (Eds.), Evidence-based approaches in positive education: Implementing a strategic framework for well-being in schools (pp. 1–26). Springer.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education,8(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006

Zhang, H., Estabrooks, L., & Perry, A. (2019). Bringing invention education into middle school science classrooms: A case study. Technology & Innovation,20(3), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.21300/20.3.2019.235

Zhang, H., Jackson, D., Kiel, J., Estabrooks, L., Kim, S. L., Kim, D., Couch, S., & Barnett, G. M. (2021). Heat reinvented: Using a lunch box–design project to apply multidisciplinary knowledge and develop invention-related practices. Science Scope,45(1), 28–37.

Zhang, H., Couch, S., Estabrooks, L., Perry, A., & Kalainoff, M. (2023). Role models’ influence on student interest in and awareness of career opportunities in life sciences. International Journal of Science Education Part B. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2023.2180333

Funding

'Open Access funding provided by the MIT Libraries' This study was funded by the Lemelson Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Couch, S.R., Kalainoff, M.Z. Transforming a National Invention Education Program through a Strength-based Approach. TechTrends 68, 589–609 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00953-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00953-2