Abstract

This study identifies competencies specific and beneficial to online high school teachers that are modifying their own courses. Existing instructional design standards, available to guide online teachers, are not only too numerous, they are also inconsistent. Moreover, a lack of clarity exists about which specific standards benefit this emerging professional group in the process of developing and revising their courses. The Delphi design enabled participants in related fields and separated by physical distance to make and refine judgments without stress and with anonymity, to achieve consensus on specific competencies. Based on this consensus, online high school educators now have a clearly defined set of instructional design competencies that will support modifying learning objects within their classes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Twelve years ago, I taught my first online class. The online class was simply a PDF of a correspondence or print course that the school had been using. What I saw lacking in that first course was and continues to be problematic: many online courses only present information to students and they are educationally ineffective (Merrill 2008). Moller et al. (2012) indicated that distance learning should not just be driven by information presentations, but should also be driven by sound instructional approaches. Many online educational courses, including the first one I taught, are difficult to endure for students because content produced by online teachers do not follow instructional principles that are important for student learning (Merrill 2008).

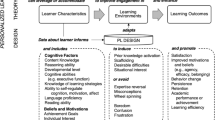

This study identifies instructional principles, specifically instructional design competencies, that benefit teachers of online high school courses as they modify learning objects (LO), that are, self-contained, reusable smaller units of learning that can be aggregated into larger collections of content. The article concludes with a practical checklist of questions and suggestions based on the competencies identified that should be considered when an online high school teacher is modifying a LO in their own class. For the purposes of this study, a competency is defined as “a knowledge, skill or attitudes that enables one to effectively perform the activities of a given occupation or function, to the standards expected in employment” (Richey et al. 2001, p. 31). Standards are competencies that have been adopted by an organization.

There is a plethora of research on creating and teaching online courses; however, there is limited research on what instructional design competencies teachers need to employ to successfully modify LO within their online courses. Designing and developing online courses is very different and more complicated than face-to-face courses (Wray et al. 2008; Siragusa 2000). Modifying an online course is similarly complicated, as it involves adapting content and assessment, using the correct technologies, and communicating effectively with students via these technologies. Often, teachers of online courses will modify their course content (Davis and Smith 2007) to suit the needs of their students and their pedagogy; however, as Wray et al. (2008) noted, few faculty have been taught the technical and pedagogical proficiencies needed to develop quality content for the online environment. While teachers are content experts, without awareness of eLearning tools and standards, they cannot develop or edit online courses effectively (Cleveland-Innes and Garrison 2012; Oliver et al. 2010). Furthermore, while Ferdig et al. (2009) found support for successful practices related to K-12 online schools, other evidence indicates that online teachers need instructional design skills to develop or modify their courses (Dawley et al. 2010). The competencies identified below can guide online teachers toward this end.

It is clear, that online school teachers request professional development on instructional design principles (Dawley et al. 2010) and that administrators indicate a need for teacher training (Day et al. 2012) that includes instructional design principles and competencies. The present study addresses this need and builds on work such as Major (2015) and Palloff and Pratt (2013), which indicate that training is especially needed when developing unique and educationally effective content for online courses. Too often teachers are left to consult conflicting articles, books and organizations to help them modify their courses for an online environment. This study makes available a consistent and clear set of instructional design competencies to guide both online high school educators and the professionals responsible for preparing and hiring them.

Methods

This study employed a Delphi design to attain consensus among 38 participants from five groups (high school online practitioners, instructional design academics, university pre-service instructors, online high school administrators and high school online instructional designers) to determine which instructional design competencies from seven organizations (see Table 1) are best suited for online high school teachers who modify their own courses. A Delphi design is a robust method for determining which policies, positions—or, in this case, which instructional design competencies—are considered the most essential (Scheibe et al. 1975).

There are multiple ways of conducting research using the Delphi design, including the paper-and-pencil and computer-based method (Linstone and Turoff 1975). The RAND Corporation developed the Delphi design in the 1950s to achieve trustworthy agreement in judgment of experts (Dalkey and Helmer 1963). It is useful specifically for a group communication process (Linstone and Turoff 1975) and for minimizing conflict in studies for which disagreement among participants is potentially high, as when participants come from different professions and backgrounds (Melpignano and Collins 2003). While a high attrition rate and participant access to the Internet and other technology issues are disadvantages (Donohoe et al. 2012), the Delphi design allows participants to make and refine decisions with anonymity (Donohoe and Needham 2009; Edgren 2006), and thus without pressure (Rowe and Wright 1999) from other participants or from the researcher.

To reach a final consensus on competencies for online high school teachers, this study used the Likert-type rating scale, which Scheibe et al. (1975) describe as “quick, easy to comprehend, and psychologically comforting” (p. 267) for participants. Though challenging, choosing participants who sufficiently understand the problem at hand is essential in a Delphi design study (Linstone and Turoff 1975). As well, there is a need to mitigate potential “misunderstanding…from differences in language and logic if participants come from diverse cultural backgrounds” (Linstone and Turoff 1975, p. 7). Thus, this study targeted participants who not only understood the problems facing online high school teachers, but who were willing to work with each other to come up with a solution.

I found the participants by several methods, including conducting a systematic Internet search for online high schools and post-secondary schools that taught pre-service teachers and instructional design in Canada and the U.S. I also used academic membership lists and listservs. I sent over 800 individual questionnaires via email to potential participants.

Participants were drawn from five groups:

-

Practitioners with at least five years of online high school experience, who worked full time in an online high school environment and were directly involved in developing and editing course content.

-

Instructional design academics with a doctorate in instructional design or related field, who were up to date with current instructional design standards.

-

University pre-service instructors who worked with pre-service teachers for at least five years, had online teaching experience, and created online educational content.

-

Online school administrators who had online teaching experience and at least five years of experience in their current administrative positions.

-

Practicing instructional designers who created high school online courses as a whole or in part.

I required participants to have at least five years of experience in their field, though most had over ten years of experience. Eighteen out of 31 participants held doctoral degrees, 11 held master’s degrees, and two had bachelor’s degrees.

The study had three rounds and took 41 days to complete. The participants had ten days in each round to return a completed instrument, which was in PDF form to allow participants to save their answers and come back to them later if needed. A one-week break followed each round to allow time to compile results and create the next instrument. To increase completion rates, I mailed reminder letters (via Postal Service) the day after sending the instrument by email. I also sent a reminder email two days prior and one day after the due date for each round to any participant who had not yet submitted the instrument. I also planned to telephone any participant who had not submitted their instrument three days after it was due.

Over the course of three rounds, participants reduced 116 instructional design competencies, gathered from seven organizations, to 10 competencies that were most applicable for online high school educators who modify their own courses. Participants in this study acted as one whole group to move a competency forward. Thus, during the first round, competencies ranked as ‘Strongly Agree’ by 60% of participants or more indicated agreement among participants in the first round. A consensus of 60% was used in the first round to make sure none of the items would be left out. The remaining two rounds used a 75% ranking ‘Strongly Agree’ to indicate consensus on an item. While the use of percentage has been commonly used to indicate agreement among participants, there is not an agreed upon definition of what constitutes consensus in a Delphi study (Hasson et al. 2000). This study followed the majority of studies in using a 75% ranking ‘Strongly Agree’ to indicate consensus on an item (Johnston et al. 2014; Penciner et al. 2011; York and Ertmer 2011).

To complete each instrument, the participants were asked to use their professional judgement to evaluate a list of competencies using a Likert scale to indicate whether the online high school teachers required the listed competency to alter course content, assignments, LO and other elements:

-

Strongly agree – The competency should be required;

-

Agree – It is a suggested competency, but not required;

-

Neutral – Do not have an opinion;

-

Disagree – Probably should not be a competency;

-

Strongly disagree – The competency should not be required

The most important item on the Likert scale for this study was ‘Strongly Agree’. This ranking determined whether a competency moved to the next round.

Table 1 describes the different organizations that have created competencies and/or standards. Only instructional design competencies from these organizations were used in this study.

Results

First Round

Of the 38 participants who initially agreed to participate, 32 participants from five different groups returned their surveys (84% response rate). The first round included 116 instructional design competencies from seven different organizations (see Table 1). Competencies with 60% or higher ranked as ‘Strongly Agree’ indicated agreement among participants and were moved to Round 2. Thirty-one (27%) of the original 116 competencies moved forward to Round 2. The last column of Table 1 presents the number of competencies from each organization that moved through each of the three rounds. I did not ask participants who failed to respond to the first survey to participate further.

Second Round

Thirty-one participants responded to the second round of this Delphi study (82% response rate). During the second round, competencies with 75% or higher ranked as ‘Strongly Agree’ indicated agreement among participants and were moved to Round 3. Twelve (10%) of the original 116 competencies moved forward to Round 3.

Third Round

Round 3 finalized the list of instructional design competencies for online high school teachers who were able to modify their own courses. This round also had 31 participants responding to this Delphi study (82% response rate). During the third round, competencies with 75% or higher ranked as ‘Strongly Agree’ indicated agreement among participants and I moved those to the final list. Two competencies did not move from Round 3 to the final list. The final list has 10 competencies.

Final List of Competencies and Round three Consensus Percentages

-

1.

Communicate effectively in visual, oral and written form. (Richey et al. 2001; Koszalka et al. 2013) (94%)

-

2.

Information presented in the learning object is accurate. (BC 2010) (94%)

-

3.

The online teacher knows and understands appropriate use of technologies to enhance learning. (iNACOL 2011) (87%)

-

4.

Candidates demonstrate ethical behavior within the applicable cultural context during all aspects of their work and with respect for the diversity of learners in each setting. (AECT 2012) (87%)

-

5.

The teacher models, guides and encourages legal, ethical, safe and healthy behavior related to technology use. (SREB 2006) (87%)

-

6.

The online teacher is able to arrange media and content to help transfer knowledge most effectively in the online environment. (iNACOL 2011) (84%)

-

7.

Content is presented in a logical sequence based on the learning outcomes. (BC 2010) (81%)

-

8.

The teacher plans, designs and incorporates strategies to encourage active learning, interaction, participation and collaboration in the online environment. (SREB 2006) (81%)

-

9.

The online teacher is able to create and modify engaging content and appropriate assessments in an online environment. (iNACOL 2011) (81%)

-

10.

Candidates demonstrate the ability to select and use technological resources and processes to support student learning and to enhance their pedagogy. (AECT 2012) (77%)

As was expected from other Delphi studies (Johnston et al. 2014; Penciner et al. 2011; and York and Ertmer 2011) with this instrument, none of the 10 competencies that met the criteria for the final list were rated ‘Strongly Agree’ by 100% of participants. As a group, pre-service instructors and practitioners each rated ‘Strongly Agree’ on the highest number of competencies. Table 2 explains the competencies by participant group and how each group selected ‘strongly agree’ for each of the competencies.

Table 2 illustrates how each of the participant groups rated each of the competencies. Pre-service instructors had the most unanimous ratings, with eight competencies (numbers 1–5, 7, 8 and 10) rated ‘Strongly Agree’ by all participants in the category. The first four competencies were rated ‘Strongly Agree’ by at least 75% of participants across all participant categories. All the competencies increased in the number of participants selecting ‘Strongly Agree’ throughout the three rounds. Competencies 4 and 5 had the greatest changes from round one to round three with 21% and 26% respectively, while the remaining competencies increased anywhere from 4% to 12%. The application section of this article will further explain the meanings of the competencies and how they can be used.

Twenty-six of the 31 participants made 136 comments throughout the study. Most of the comments asserted the importance of technology skills and professional development for teachers modifying their own courses. Comments ranged from the importance of online teachers having access to technicians for help with the learning management system to teachers keeping up with technology changes themselves.

On one hand, technology was seen as an essential competency for teachers, as Participant 4 indicated: “Candidates should have some knowledge of online technology infrastructure that they can use to better their course; however, knowledge for maintaining the entire infrastructure is a plus but not a necessity.” On the other hand, requiring too many technology skills was seen as a burden to instructors:

“The pace of technology will require ongoing development of the instructional skills to keep pace. These courses should be developed to focus on specific instructional skills in a way that does not overburden the online professional. Since connection with students will still be a priority, for many reasons, not all-online instruction should be conducted in the online environment! There must still be a human element and face-to-face conversations within the professional realm.” (Participant 3)

Several participants emphasized that many teachers simply do not have the time, resources, ability, or the professional obligation to keep up with technology. Many participants also highlighted their concerns regarding online high school teachers instructional design training. One participant noted that there is limited professional development with respect to instructional design that might lead to creativity and student success in online courses. This concern is indicated in the following comment:

“The development and maintenance of all the associated competencies may distance the teacher from the learner and create a very regimented online environment, lacking in the flexibility to create. Even the most highly refined and detailed online class may be lacking in the one key element that guides learning and creates the 'connections' that encourage success.” (Participant 3)

A few participants voiced that they did not believe a teacher should edit their own courses. These participant comments discussed the traditional role of the teacher, whose main job is to interact with the students, versus the role of the instructional designer whose main task is to create an engaging course. This uneasy movement between roles is shown in the following observation by a participant:

Since the designer is also the instructor, as a matter of usual skills and ability, I don't believe that high school teachers should become designers. It would be nice for teachers to have instructional design skills but it should not be required that they do. They should have design support when delivering online materials and not be relied upon to also be the designer.” (Participant 15)

Discussion

If online teachers are to take seriously what students need to learn, then teachers will require professional development and support. As I explained previously, research has shown there is a need for professional development and teachers are asking specifically for professional development that includes instructional design principles and competencies (Dawley et al. 2010 and Day et al. 2012). Various organizations (see Table 1) have developed competencies for online courses and for the instructors who teach them that could be used for professional development. It is unreasonable to expect a teacher or an administrator to scrutinize these organizations and assess hundreds of individual instructional design competencies to determine how to modify a single learning object. Thus, the instructional design field needs to decide which instructional design competencies to prioritize. This study used participants to select from seven trusted organizations the instructional design competencies most relevant and beneficial for high school teachers who modify their own courses. Online teachers should think about these competencies when they modify a LO; I offer a concrete checklist (detailed below) as one example of how a teacher might apply these competencies.

Not surprisingly, many of the competencies fall under the heading of “communication” in some way. Previous research supports this emphasis on communication. Rice (2012) indicates that for an online student to succeed the most important element is teacher-student interaction, and for this reason, as indicated in Competency #1, the online teacher must be adept and skilled in both oral and written communication. Competency #8 indicates that the online teacher should encourage interactions, participation and collaboration. Oliver et al. (2009) also found that students expect support and guidance from their teacher in communicating with their peers and the teacher. Dobson et al. (2011) emphasize that teachers need to obtain and keep the attention of their students. Competency # 9 indicates that the online teacher should be able to modify content that engagingly focuses the attention of the student. To grab the attention of students online or in the classroom and direct them towards content requires effective communication; for online courses, where distance in time and space comes into play, effective communication relies on effective use of technology. Competencies #3 and #10 indicate that the selection and appropriate use of technologies to enhance learning is significant; this is also identified in Palloff and Pratt (2011) of the criteria for an excellent online teacher. Recent studies (Rice 2012; Palloff and Pratt 2011; and Oliver et al. 2009) and the results of this study indicate the primary importance of communication in online courses. The online teacher must be able to substitute the communicative value of facial cues or body language used in traditional classrooms through the visual (video), oral (audio; telephone), and written forms (digital content and email) specific to the online environment.

Re-Wording

Consistent instructional design competencies for online high school teachers are necessary for logic, accuracy, and maintaining the message. I slightly reworded the final list of ten competencies below from the instrument competency list to help teachers understand what is being conveyed. For example, competencies 4, 6 and 7 used the term “online teacher”; 5 and 9 used “teacher”; and 8 and 10 used “candidates”. I changed these to “online high school teacher”. The re-wording ensures consistency among the competencies.

Application

Teachers are not trained as instructional designers. For example, although they may be teaching online, teachers are not trained to create LO such as graphics or videos for an online environment. Whereas education programs tend to teach pedagogy for a face-to-face classroom, for online education, teachers must become competent in making or revising more complicated LO.

Consider a scenario in which an online teacher has a graphic of a pamphlet that is difficult to read because the letters and words are blurry. The graphic had been used in a previous course taught by a different teacher many years ago. It is a photocopy, of a photocopy, of a photocopy—something many teachers often come across. As a LO, this graphic is problematic and needs modifying for several reasons as the queries in the checklist reveal. Most obviously, when looking at a graphic such as this, teachers will realize that adaptive technology cannot read it to a visually impaired student; the technology text-to-voice cannot translate images, only text. The checklist below guides us to understand several other problems with this graphic.

From the checklist below, some items or questions the online teacher modifying the above described LO should ponder are: Is the LO written in a clear, concise and grammatically correct form? Yes, the text on the graphic is correct, but quite fuzzy and difficult to read even for a visually able student. Is the source of the information credible? Yes, the pamphlet came from a credible source. Can assistive technology be used with the LO? No, because it is a copy of a copy and a poor quality one at that, it could not be read by adaptive technology. If the teacher typed out the graphic and recreated the pamphlet textually, it would be easier to read and the adaptive technology can be used. Does the LO comply with intellectual property rights and fair use standards? No, permission was not obtained to use the resource. There was not a letter in the course for the teachers indicating that the course has the right to use it. This alone may mean the graphic needs to be wholly modified or replaced, although for educational purposes some images may be used without copyright permission. Does the new LO have breadth, depth and is it current? It is not up to date with today’s information and therefore will have to be made more current.

The list below does not work for every learning object. For example, if the revised image does not have any text then competencies that deal with text may not be applicable. The online teacher will need to select which items are applicable.

I developed the checklist below drawing on my own experiences as an online teacher and online course developer with 12 years of experience, and over 22 years of teaching and mentoring. I also returned to the organization that first developed a particular competency to see if they had advanced the competency in any useful manner for the teacher. For example, the SREB, iNACOL, BC and IBSTPI (See Table 1 for acronyms) competencies have suggestions for supporting their competencies, whereas the AECT competencies do not.

The following is the checklist of instructional design competencies for online high school teachers and questions which they should ponder when modifying learning objects.

Checklist

The online high school teacher who is modifying their own course should be able to:

-

1.

Communicate effectively in visual, oral and written form. (Richey et al. 2001; Koszalka et al. 2013)

IBSTPI (Koszalka et al. 2013) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Is the LO written in a clear, concise and grammatically correct form?

-

Does the LO have a clear message or purpose?

-

Does the visual (images, videos, simulations etc.) attract and engage the students?

This study also suggests:

-

Is the LO written in an age appropriate manner?

-

Does the LO ensure screen readability (font, course, spacing etc.) and has no distractions?

-

Does the LO (video and audio) use dynamic voice and appropriate pace?

-

Is there enough white space, so that student is not overwhelmed?

-

Does the new LO make the course page load slowly?

-

2.

Present accurate information in the learning objects. (BC 2010)

BC (2010) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Is the information in the LO accurate?

-

Does the LO have accurate directions?

-

Is the LO presented in a logical sequence?

This study also suggests:

-

Is the source of the information credible?

-

Did the information fact check? Or do you trust the source of the information?

-

Is there bias in the LO?

-

Is the information in the LO age appropriate?

-

Is there content in the LO that distracts the learner?

-

Is the LO complete? Is there any missing information?

-

Does the LO gain interest of the learner?

-

3.

Know and understand appropriate use of technologies to enhance learning. (iNACOL 2011)

iNACOL (2011) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Can the LO be incorporated into the Learning Management System?

-

Does the LO align with the course objectives and state or provincial standards?

-

Is the LO appropriate for the learner’s age group?

-

Is the LO arranged to help transfer knowledge most effectively in the online environment?

This study also suggests:

-

Is the technology (both software and hardware) that is being used for the LO best suited to enhance learning?

-

Is the use of technology will be motivating?

-

Can assistive technology can be used with the LO?

-

Does the LO incorporate the existing course technology or will the student need to download new software?

-

4.

Demonstrate ethical behavior within the applicable cultural context during all aspects of their work and with respect for the diversity of learners in each setting. (AECT 2012)

This study suggests:

-

Does the learning objective or learning materials account for the diversity of learners on the gender spectrum?

-

Does the learning objective and learning materials acknowledge the diversity of learners in the context of varying cultures, ethnicities, and social backgrounds?

-

Do you have intellectual property rights to use or modify the learning object?

-

Assistive technology can be used with the learning object?

-

All your learners will be able to use the learning object?

-

Netiquette (respect and courtesy) expectations are being followed?

-

5.

Model, guide and encourage legal, ethical, safe, and healthy behavior related to technology use. (SREB 2006)

SREB (2006) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Does the LO comply with intellectual property rights and fair use standards?

-

Does the LO follow the school’s Acceptable Use Policy?

-

Does the LO keep the student’s information private?

This study also suggests:

-

Are the LOs cited properly?

-

Is there an alternative way to show the LO when using technology?

-

Does the LO create a positive digital footprint?

-

6.

Effectively arrange media and content to help transfer knowledge. (iNACOL 2011)

iNACOL (2011) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Does the LO work with the Learning Management System?

-

Is the LO arranged to help transfer knowledge effectively in the online environment?

-

Does the LO align with the course objectives, state and local standards?

-

Is the LO using developmentally appropriate software?

This study also suggests:

-

Is there a better LO that would help with learner understand the learning objective?

-

Are there parts of the content missing or is there too much content?

-

7.

Present content in a logical sequence based on the learning objectives. (BC 2010)

BC (2010) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Are the LOs presented in a logical sequence and based on the learning outcomes?

-

Is the LO organized and content sequenced in a way that is appropriate for the subject matter and age of the intended audience?

This study also suggests:

-

Is the content in the LO introduced gradually, versus seeing all the content right away?

-

8.

Plan, design and incorporate strategies to encourage active learning, interaction, participation and collaboration. (SREB 2006)

SREB (2006) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Does the LO acknowledge the cultural background and learning needs of non-native English speakers?

-

Does the LO encourage appropriate group interaction?

-

Does the LO encourage interaction with other students?

This study also suggests:

-

Does the LO incorporate scaffolding strategies to promote or encourage interactions?

-

Does the LO encourage interaction with the teacher or the course?

-

9.

Create and modify engaging content and appropriate assessments. (iNACOL 2011)

iNACOL (2011) suggestions for supporting this competency:

-

Does the LO engage the student?

-

Does the LO incorporate multimedia and visual resources?

-

Does the LO align with student’s different visual, auditory, and hands-on ways of learning?

This study also suggests:

-

Does the new LO provide interaction for the student?

-

Does the assessment match the learning objective?

-

Is the new assessment measurable?

-

Is the LO content or assessment age appropriate?

-

Is the new assessment consistent with the course content and activities?

-

Are there different types of LOs?

-

Does the new LO have breadth, depth and currency?

-

10.

Demonstrate the ability to select and use technology resources and processes to support student learning and to enhance their pedagogy. (AECT 2012)

This study suggests:

-

Why did you use this technology? Did you use a logical approach to decide which technology to use?

-

Will the new technology resource be conducive to student learning?

-

Will the students have the technical skills needed and/or possess access to the technologies to use the LO?

-

Does the use of the technology resource follow with the school’s technology use policies?

-

Is the technology suitable for the LO?

-

Does the teacher know the different software available to edit LOs?

-

Does the teacher know how to upload the new LO into the course?

As the reader can see, each of the competencies should be considered when a teacher is modifying a LO. Using the checklist as I did in the example of a copy of a copy, the online teacher now knows which instructional design competencies to focus on when revising LOs in their own course. If communication is important to online high school students, then the following practical applications gives teachers some questions to ponder when the teacher is working on the LO.

Limitations

There are a few limitations with this study. First, the study assumed that all available competencies were available on the initial instrument. Second, the participants were assumed to represent the whole population and to understand what each item on the instruments meant. The final assumption is that all participants selected the correct definition from the Likert Scale, based on their prior knowledge. The study was limited by the limitations of the Delphi design, as well. This study was limited to 38 participants from the following five groups: practitioners, instructional design academics, university pre-service instructors, online school administrators, and practicing high school designers. The groups were not evenly distributed and were mostly from the United States and therefore may not represent an international consensus. Limitations, such as use of the Internet, attrition rates, consensus among participants and participants themselves, exist with usage of the Delphi design as a research method. The initial instrument had 116 items and for some participants it was time-consuming to complete. For this study, a 60% ranking ‘Strongly Agree’ was used to indicate consensus on an item in the first round to make sure an item was not missed. Item numbers 4, 5 and 10 would not have made it through round one if 60% ranking on ‘Strongly Agree’ was not used.

Closing Considerations

The presented list of instructional design competencies and questions targets practicing online high school teachers. This checklist of questions is not all encompassing, of course, but it is a place to begin applying the competencies that participants in the study found to be most important when modifying LOs. Since none of the competencies had 100% acceptance from all participant groups, there is future work to be done, such as clustering the groups differently. For example, if only using instructional designer academics or only practicing teachers are asked to rank competencies, will the final competencies be similar to this study? Future research also needs to test the competencies query checklist with online high school teachers, to examine what is missing in the way the competencies. By doing so, the day-to-day application of these competencies can be assessed.

References

Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (2012). AECT standards for professional education programs (2012 version). Retrieved from http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/aect.siteym.com/resoubethlerce/resmgr/AECT_Documents/AECT_Standards_adopted7_16_2.pdf.

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2010). Standards for digital learning content in British Columbia. Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Education. Retrieved from www.bced.gov.bc.ca/dist_learning/docs/digital_learning_standards.pdf.

Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2012). Higher education and postindustrial society: New ideas about teaching, learning, and technology. In L. Moller & J. B. Huett (Eds.), The next generation of distance education. New York: Springer.

Dalkey, N., & Helmer, O. (1963). An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science, 9(3), 458–467.

Davis, N., & Smith, R. (2007). Research committee issues brief: Professional development for virtual schooling and online learning. International association for K-12 online learning. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED509632.pdf.

Dawley, L., Rice, K., & Hincks, G. (2010). Going virtual! 2010: The status of professional development and unique needs of K-12 online teachers. Retrieved from http://edtech.boisestate.edu/goingvirtual/goingvirtual3.pdf.

Day, S., Picciano, A., & Seaman, J. (2012). A descriptive analysis of online learning in American high schools: Views from their principal's office. Paper presented at the American education research association. BC: Vancouver.

Dobson, S., Bromley, L., & Dobson, M. (2011). How to teach: A handbook for clinicians. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Donohoe, H., & Needham, R. (2009). Moving best practice forward: Delphi characteristics, advantages, potential problems, and solutions. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(5), 415–437. doi:10.1002/jtr.709.

Donohoe, H., Stellefson, M., & Tennant, B. (2012). Advantages and limitations of the e-Delphi technique: Implications for health education researchers. American Journal of Health Education, 33(4), 38–46. doi:10.1080/19325037.2012.10599216.

Edgren, G. (2006). Developing a competence-based core curriculum in biomedical laboratory science: A Delphi study. Medical Teacher, 28(5), 409–417. doi:10.1080/01421590600711146.

Ferdig, R., Cavanaugh, C., DiPietro, M., Black, E., & Dawson, K. (2009). Virtual schooling standards and best practices for teacher education. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 17(4), 479–503.

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01567.x.

International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL). (2011). National standards for quality online teaching. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/research/nationalstandards/iNACOL_TeachingStandardsv2.pdf.

Johnston, L. M., Wiedmann, M., Orta-Ramirez, A., Oliver, H. F., Nightingale, K. K., Moore, C. M., Stevenson, C., & Jaykus, L.-A. (2014). Identification of core competencies for an undergraduate food safety curriculum using a modified Delphi approach. Approach. Journal Of Food Science Education, 13(1), 12–21. doi:10.1111/1541-4329.12024.

Koszalka, T., Russ-Eft, D., Reiser, R., Fernando Sr., C. A., Grabowski, B., & Wallington, C. (2013). Instructional designer competencies: The standards (4th ed.). Charlotte: Information Age.

Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (1975). Introduction. In H. A. Linstone & M. Turoff (Eds.), The Delphi method: Techniques and applications (pp. 3–12). Reading: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Major, C. (2015). Teaching online a guide to theory, research, and practice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Melpignano, M., & Collins, M. E. (2003). Infusing youth development principles in child welfare practice: Use of a Delphi survey to inform training. Child & Youth Care Forum, 32(3), 159–173 Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/journal/10566/32/3.

Merrill, D., [mdavidmerrill]. (2008, August 11). Merrill on instructional design [Video file]. Retrieved from http://youtu.be/i_TKaO2-jXA.

Moller, L., Robison, D., & Huett, J. B. (2012). Unconstrained learning: Principles for the next generation of distance education. In L. Moller & J. B. Huett (Eds.), The next generation of distance education. New York: Springer.

National Education Association. (2006). National Education Association: Guide to teaching online courses. Washington, DC: National Education Association.

Oliver, K., Osborne, J., Patel, R., & Kleiman, G. (2009). Issues surrounding the deployment of a new statewide virtual public school. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(1), 37–50.

Oliver, K., Kellogg, S., Townsend, L., & Brady, K. (2010). Needs of elementary and middle school teachers developing online courses for a virtual school. Distance Education, 31(1), 55–75. doi:10.1080/01587911003725022.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2011). The excellent online instructor: Strategies for professional development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2013). Lessons from the virtual classroom: The realities of online teaching (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Penciner, R., Langhan, T., Lee, R., Mcewen, J., Woods, R. A., & Bandiera, G. (2011). Using a Delphi process to establish consensus on emergency medicine clerkship competencies. Medical Teacher, 33(6), e333–e339. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.575903.

Rice, K. (2012). Making the move to K-12 online teaching: Research-based strategies and practices. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Richey, R., Fields, D., & Foxon, M. (2001). Instructional design competencies: The standards (3rd ed.). Syracuse University-Syracuse: Clearinghouse of Information & Technology.

Rowe, G., & Wright, G. (1999). The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: Issues and analysis. International Journal of Forecasting, 15(4), 353–375. doi:10.1016/S0169-2070(99)00018-7.

Scheibe, M., Skutsch, M., & Schofer, J. (1975). Experiments in Delphi methodology. In H. A. Linstone & M. Turoff (Eds.), The Delphi method - techniques and applications (pp. 262–287). Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Siragusa, L. (2000). Instructional design meets online learning in higher education. Paper presented at the Proceedings Western Australian Institute for Educational Research Forum 2000, Australia. Retrieved from http://www.waier.org.au/forums/2000/siragusa.html.

Southern Regional Education Board. (2006). Standards for quality online teaching. Atlanta: Southern Regional Education Board Retrieved from http://publications.sreb.org/2006/06T02_Standards_Online_Teaching.pdf.

Wilson, B. (2007). The future of instructional design (point/counterpoint). In R. Reiser & J. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and issues in instructional design and technology (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Wray, M., Lowenthal, P., Bates, B., & Stevens, E. (2008). Investigating perceptions of teaching online & F2F. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 12(4), 243–248 Retrieved from http://rapidintellect.com/AEQweb/.

York, C. S., & Ertmer, P. A. (2011). Towards an understanding of instructional design heuristics: An exploratory Delphi study. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59(6), 841–863. doi:10.1007/s11423-011-9209-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author did NOT receive research grants or funding for this study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Capella University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rozitis, C.P. Instructional Design Competencies for Online High School Teachers Modifying their own Courses. TechTrends 61, 428–437 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0204-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0204-2